The Secrets of Secrets of the Octopus

Director and cinematographer Adam Geiger dives into the process behind filming some of the ocean's most elusive animals.

"You don't have to go to outer space to encounter a completely different world, because everything underwater is so different. It's magical," says Adam Geiger, the Sydney, Australia-based director, cinematographer, and — along with his partner Colette Beaudry at SeaLight Pictures and James Cameron's Earthship Productions — executive producer of National Geographic's three-part documentary series Secrets of the Octopus.

As a documentarian with decades of credits to his name, Geiger's films have delved into diverse topics, from the Dingo of Australia's outback (Dingo: Wild Dog at War) to the intelligent urban pigeon (Pigeon Genius), and the social impact of alcohol consumption (U.S. of Alcohol). As a lifelong diver, student of marine science at Hampshire College, and mentee of Cousteau Society cinematographer Louis Prezelin (at the Brooks Institute of Photography, where Geiger learned filmmaking), "the ocean is my first love," he tells AC. For Secrets of the Octopus, he wanted to cast the elusive ocean invertebrate in a whole new light.

"There's some wonderful footage out there of people interacting with octopuses, but it doesn't always show how intelligent, curious, social, and physically amazing different species of octopus really are," he adds. "Capturing this behavior on camera could only be achieved over hours, days and weeks of filming.

Such an approach demanded more than one camera, so Geiger enlisted Australian cinematographer Rory McGuinness, ACS — his collaborator on David Attenborough's Life in Color — for the duration of the Octopus shoot, along with Maxwel Hohn and Jason Sturgis (Vancouver, BC), and Christian Demetrius (Brazil). (Camera assistant Woody Spark also stepped up to cinematography duties.)

Here, Geiger explains in his own words how filming Secrets of the Octopus called for both a highly technical and very personal approach.

“I intend to keep exploring the idea that animals have human-like traits the audience can relate to, and far more personality and awareness than we realize.”

— executive producer, director,

cinematographer Adam Geiger

MYSTERIOUS, MESMERIZING ANIMALS

"Filming natural history underwater is always a challenge, no matter where you go. Conditions can be against you: poor visibility, poor light, strong currents, and dealing with wild animals you can't control. But even in great conditions, octopuses present unique challenges: they are hard to find and can change the color, texture and shape of their body to disappear in plain sight; they have no bones, so they can squeeze through an opening the size of their eyeball; they can move easily in any direction. What's most remarkable about them is their intelligence — they are totally aware of everything around them. They have no teeth, no shell, no claws — their weapon is their brain.

"For this series, we wanted to highlight their physical, mental, and surprisingly social abilities. Each species has its own characteristics; some are wary, some are bold, and others are tremendously curious. And within those species, each individual has his or her own personality."

"First, we selected eight hero species, researched their behavior, then wrote a shooting script, which gave us a sense of each story we wanted to tell. Next, we needed to find a way to approach the octopuses without disturbing their natural behavior. To do that, we needed to gain their trust.

"With an octopus, you're very often the 'observed observer.' They'll sit there and watch you and wait for you to run out of air before they'd leave the den. [A typical scuba dive is around an hour.] We dove with rebreathers — a closed-circuit breathing apparatus where exhaled gas is stripped of carbon dioxide and enriched with oxygen, then sent back to the diver — which gave us up to four and a half hours per dive, six days a week, for up to six weeks at a time. Sometimes, we'd sit on the ocean floor for almost two hours before an animal acclimated to our presence.

"I worked with one coconut octopus in Indonesia for five days in a row. On day one, it took hours to get some fleeting behavior, but by the fifth day, it was only a few minutes after I showed up at her den — just two clam shells dug into the sand — that she came out, crawled over the camera and into my hand to say 'Hello,' and then let me follow her as she went hunting.

"As soon as an octopus leaves its den, we're rolling. Over time, we learned to notice certain behavioral cues, and that's how we were able to capture a coconut octopus — which carries seashells with it for shelter — pick up another shell and use it as a shield in a fight with a mantis shrimp, which is a level of sophisticated tool use not seen in octopus before."

A VARIETY OF CAMERA SYSTEMS

"Because our locations were so vastly different from each other — from the cold, dark North Pacific to brilliant coral reefs in the tropics, and barren, sandy plains in Indonesia — each one called for a different approach to how you film and what equipment you use."

"A Red Epic-W 8K Helium with a Nikkor 70-180mm f/2.8 was brilliant for intimate close-up work. One of our workhorse cameras was a Sony F5 with an R5 back recording 4K RAW. A Nikkor 24-70mm f/2.8 behind a 10-inch dome port gave us tremendous flexibility, especially filming small octopus. We had a couple of Sony A7S IIIs, great for their low-light capability, often recording externally to Atomos Ninja recorders in ProRes 4K RAW, (though internal recordings in XAVC-S I held up just fine and allowed us to shoot at 120 fps), and paired well with a Laowa 24mm f/14 probe lens. We also had a Sony A1, shooting in 8K and 4K, recording 8K internally and 4K to a Ninja, and two Z CAM E2-F6 6K cameras."

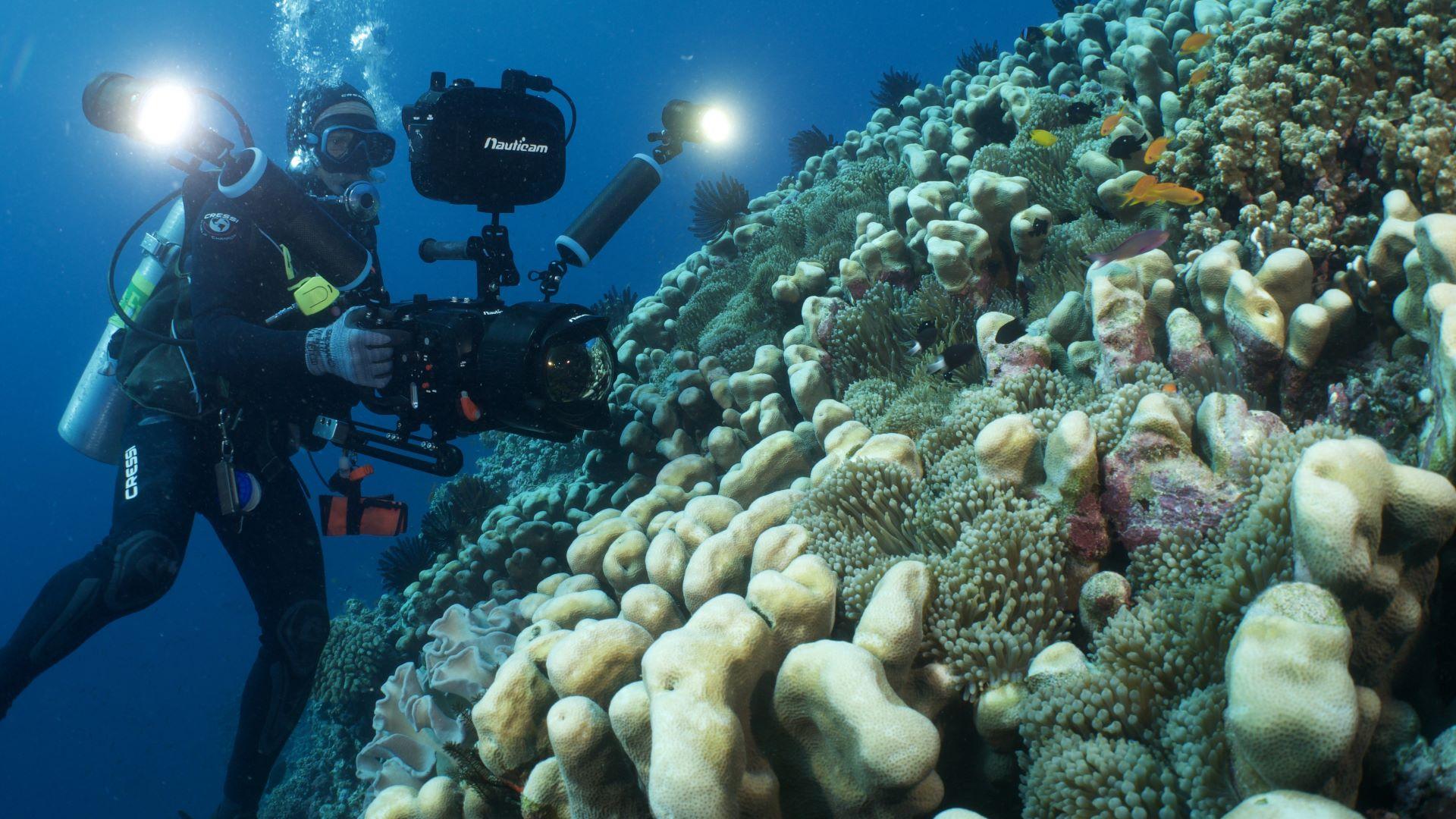

"We used a wide selection of lenses on difference cameras, allowing us to cross-shoot wide and tight. For wide-angle work, my favorite lenses are still the 50-year-old Nikonos 15mm f/2.8 and 20mm f/2.8. All of the cameras used Nauticam and Gates housings that gave us nearly as much control as you would have on the surface."

COMPLETELY DIFFERENT WORLDS

"We wanted each location and each octopus character to have a different feel, which came down to composition, exposure, depth of field, lighting, and camera movement."

"For the day octopus, we wanted broad depth of field in wide shots to show the complexity of their world. For the mimic octopus, we used a shallow depth of field to create a spooky feel. For the island octopus in the Turks and Caicos, we used a 'dirty' frame with lots of things passing in front of the lens as the octopus moved, to highlight their furtive nature. And with coconut octopus, we used long lenses for intimate portraits, and close-focus-wide angle probe lenses brought us closer to their world."

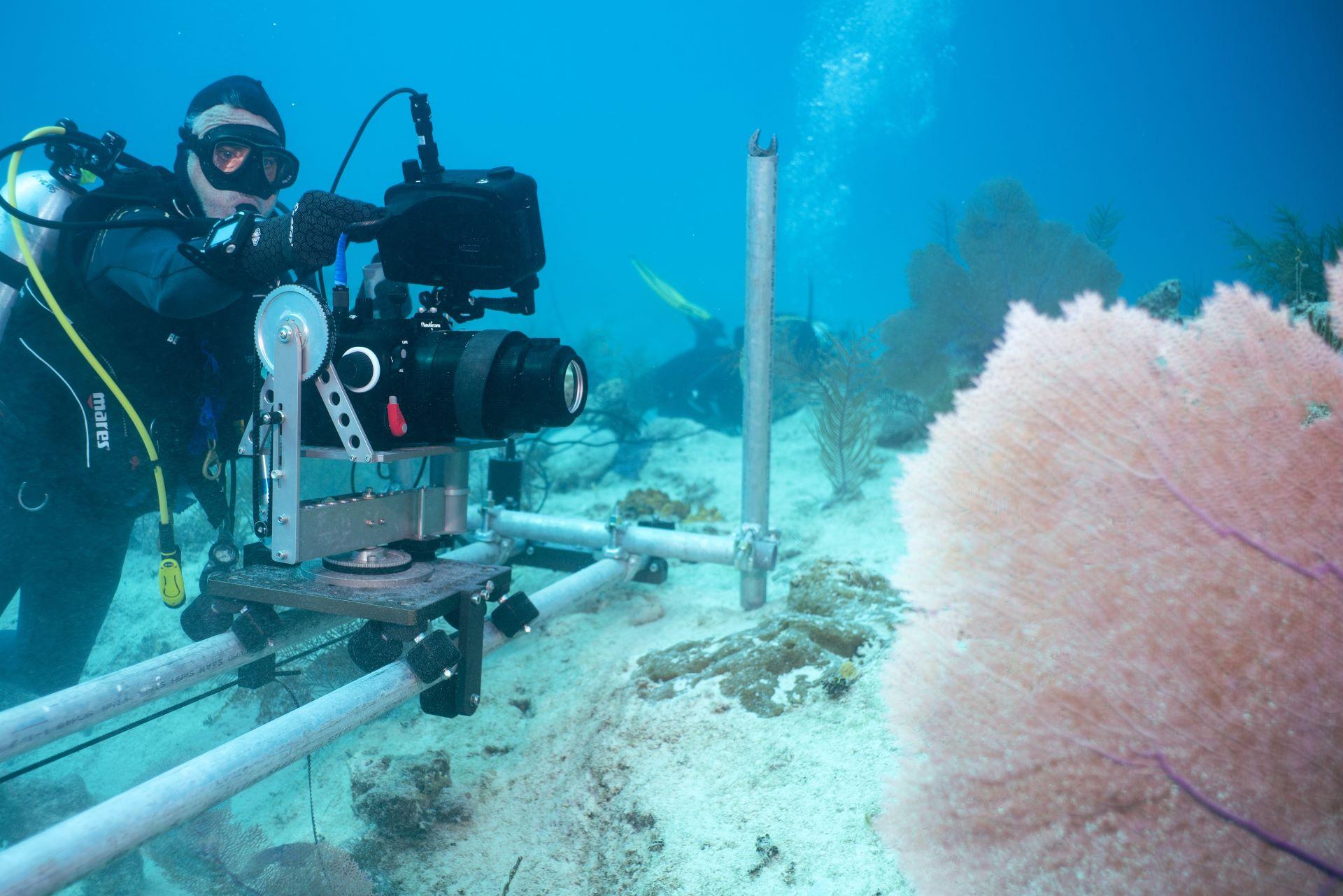

"We used SeaLight's custom-built quadpod for long-lens shots, and as a platform for our jib arm. We also used a motorized slider with a pan/tilt head, and a custom-designed camera-control unit with a monitor. The entire one-of-a-kind system could be controlled underwater from 15 feet away, minimizing our influence on the octopuses' behavior. Unfortunately, the camera's movement was limited by the slider it was attached to, and an octopus out for a jaunt quickly left us in the dust.

"Ultimately, the best platform to film octopus is in the hands of talented, experienced underwater cinematographers, who, in a near-weightless world, becomes a tripod, jib arm, dolly and slider all in one."

LIGHTING

"Warm colors are absorbed quickly underwater, so anything deeper than 10' required additional lighting to restore contrast and color. We used a variety of battery-powered lights with different output capabilities, from 18,000-lumen Bigblue dive lights down to 2,000-lumen Light & Motion lights, in varying combinations, depending on the situation, but the most important thing was that every shot felt naturally lit."

"We sometimes used two lights mounted on the camera. In low-contrast conditions, I wanted to establish a light source to avoid a flat look, so we mounted a key light on a long arm to get it away from the camera, sometimes overhead, sometimes slightly from the side, with a fill light to bring up the shadows in the foreground. We added to the lights some small, hand-fashioned elements that moved in the water, to create a natural dappling effect. For night filming in the cold and murky water of Port Phillip Bay, Australia, two Aputure 600Ds on a boat above us lit up the octopuses' world in an otherwise black void."

THE HUMAN CONNECTION

"Filming Secrets of the Octopus has been a tremendous high point in my natural history filmmaking career, and there are many moments from the making of it that I'll never forget: an island octopus, asleep and likely dreaming; a curious day octopus reaching out to touch me; our lead scientist and storyteller, Dr. Alex Schnell interacting with Scarlet the octopus for the first time was an incredibly moving experience.

"Whatever comes next, I intend to keep exploring the idea that animals have human-like traits the audience can relate to, and far more personality and awareness than we realize. I want to get my cameras into the wild, and help people reconnect with nature and understand that we're not above it, but a part of it."

For more on specialized cinematography in the natural history field, see Weird and Fascinating: Filming A Real Bug's Life.