Apocalypse Now: A Clash of Cultures

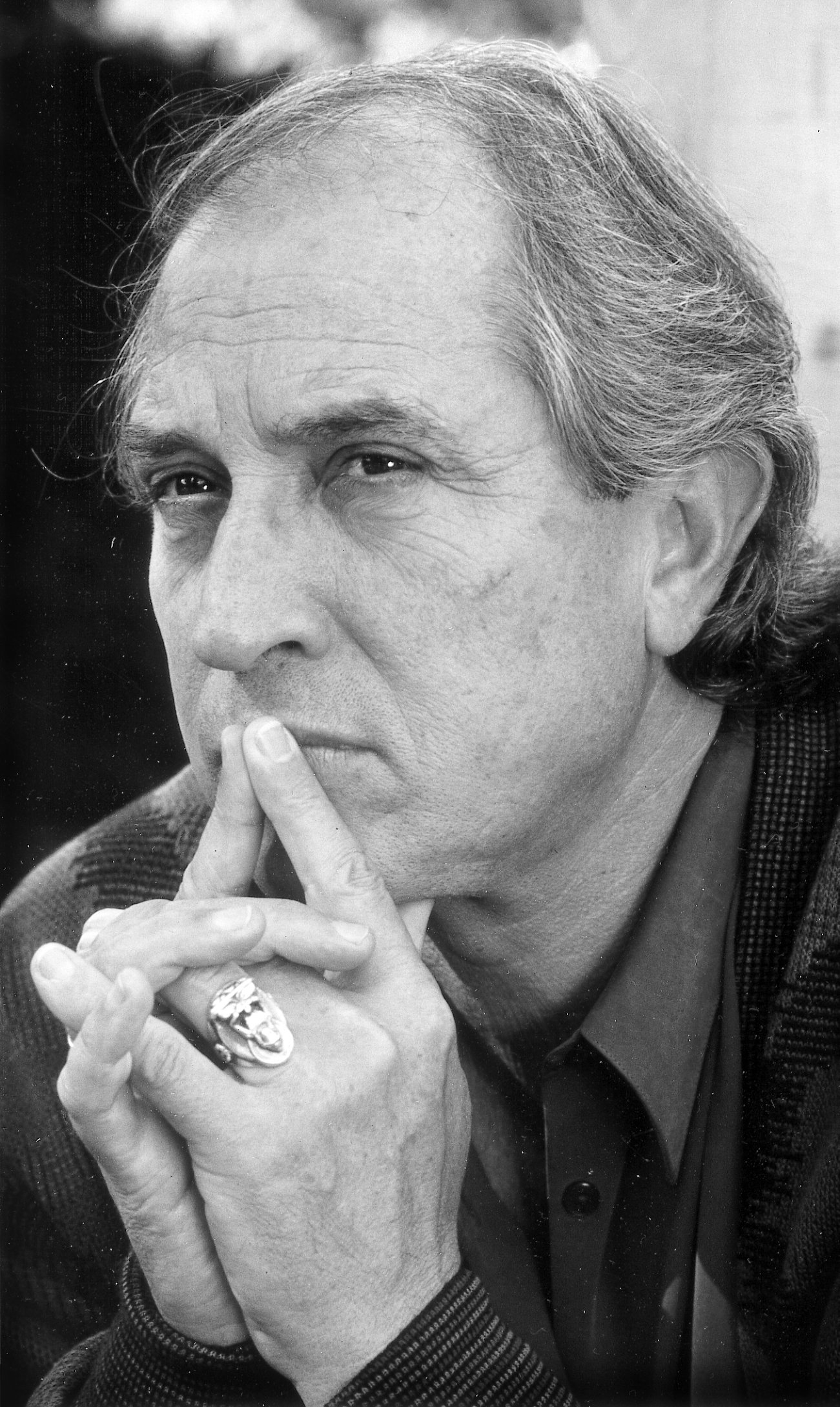

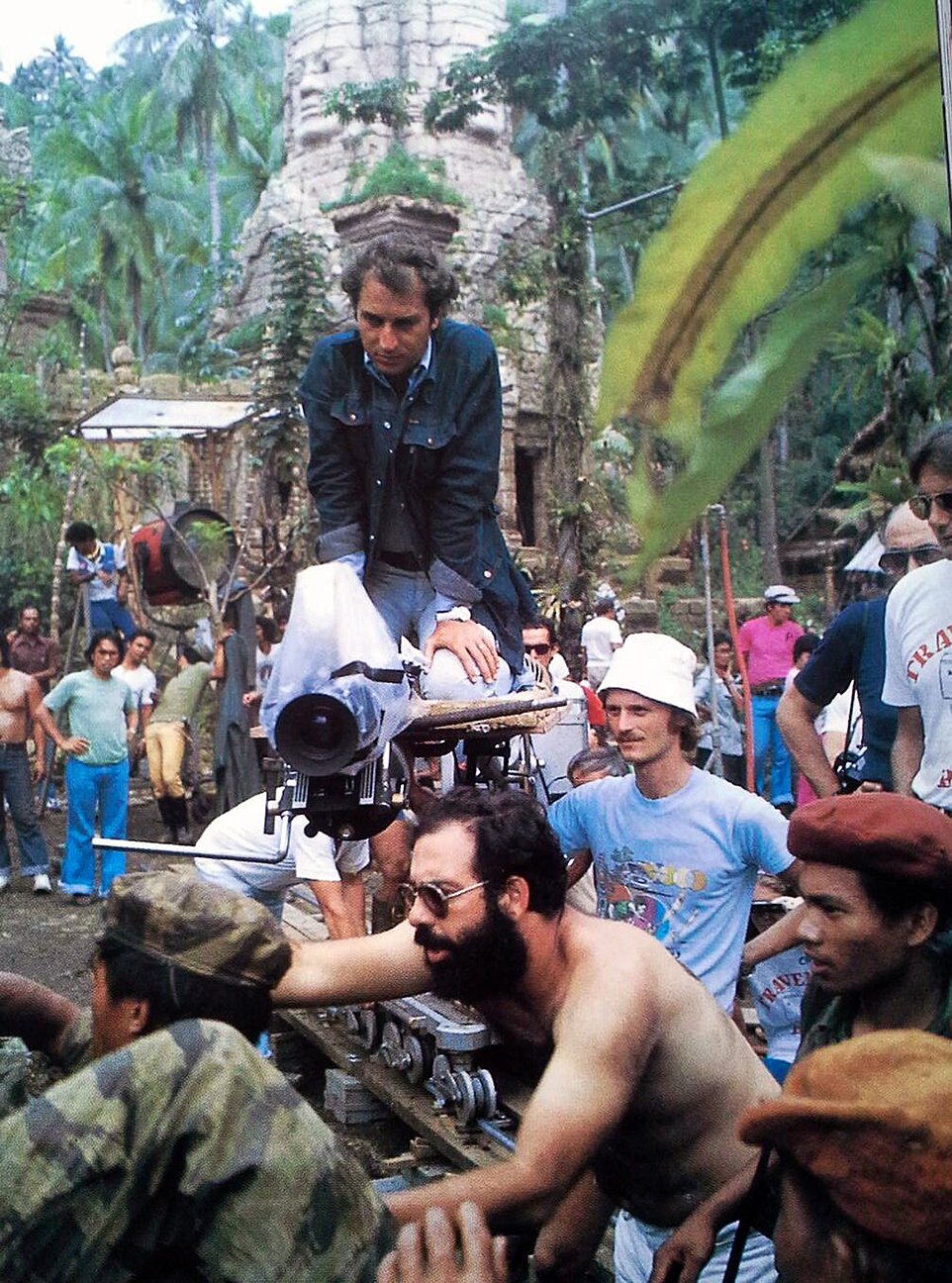

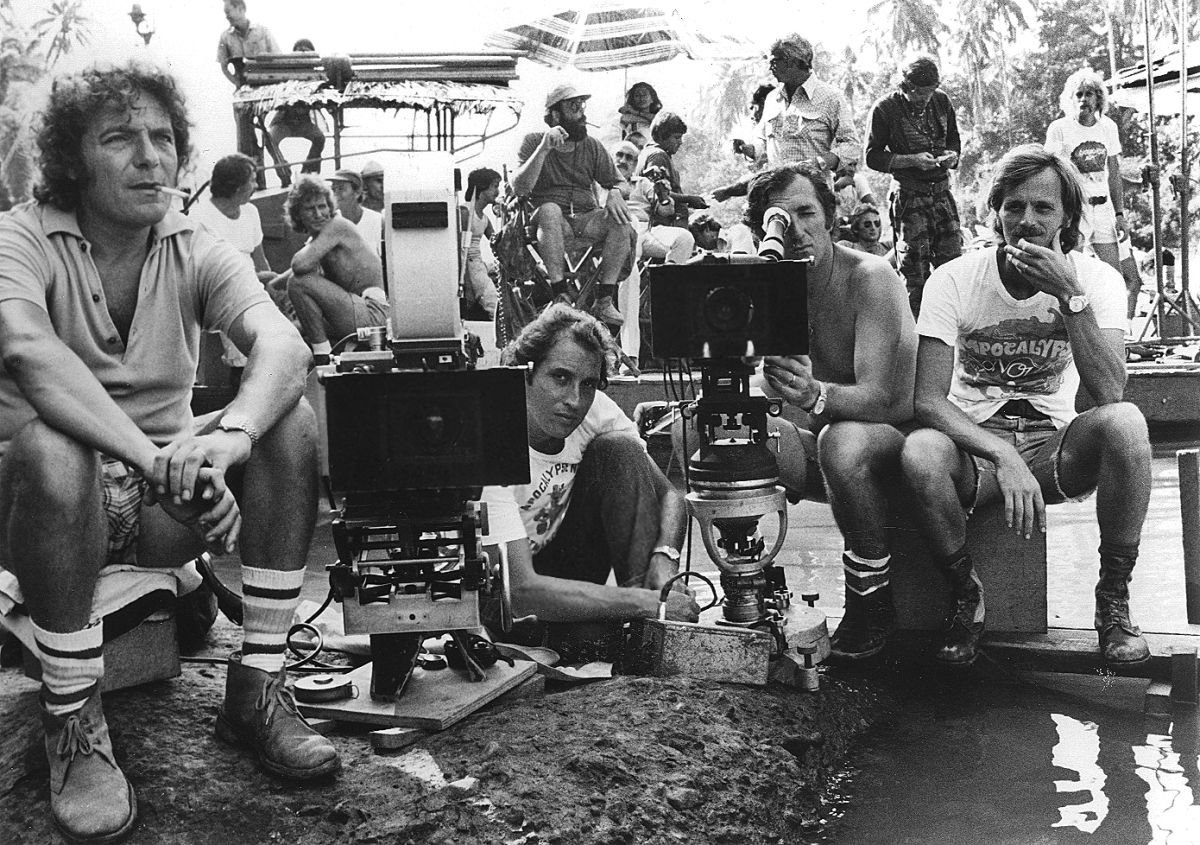

Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC recalls the photographic challenges he confronted during the tumultuous production of Francis Ford Coppola’s hallucinatory Vietnam War epic.

Interview by Stephen H. Burum, ASC and Stephen Pizzello

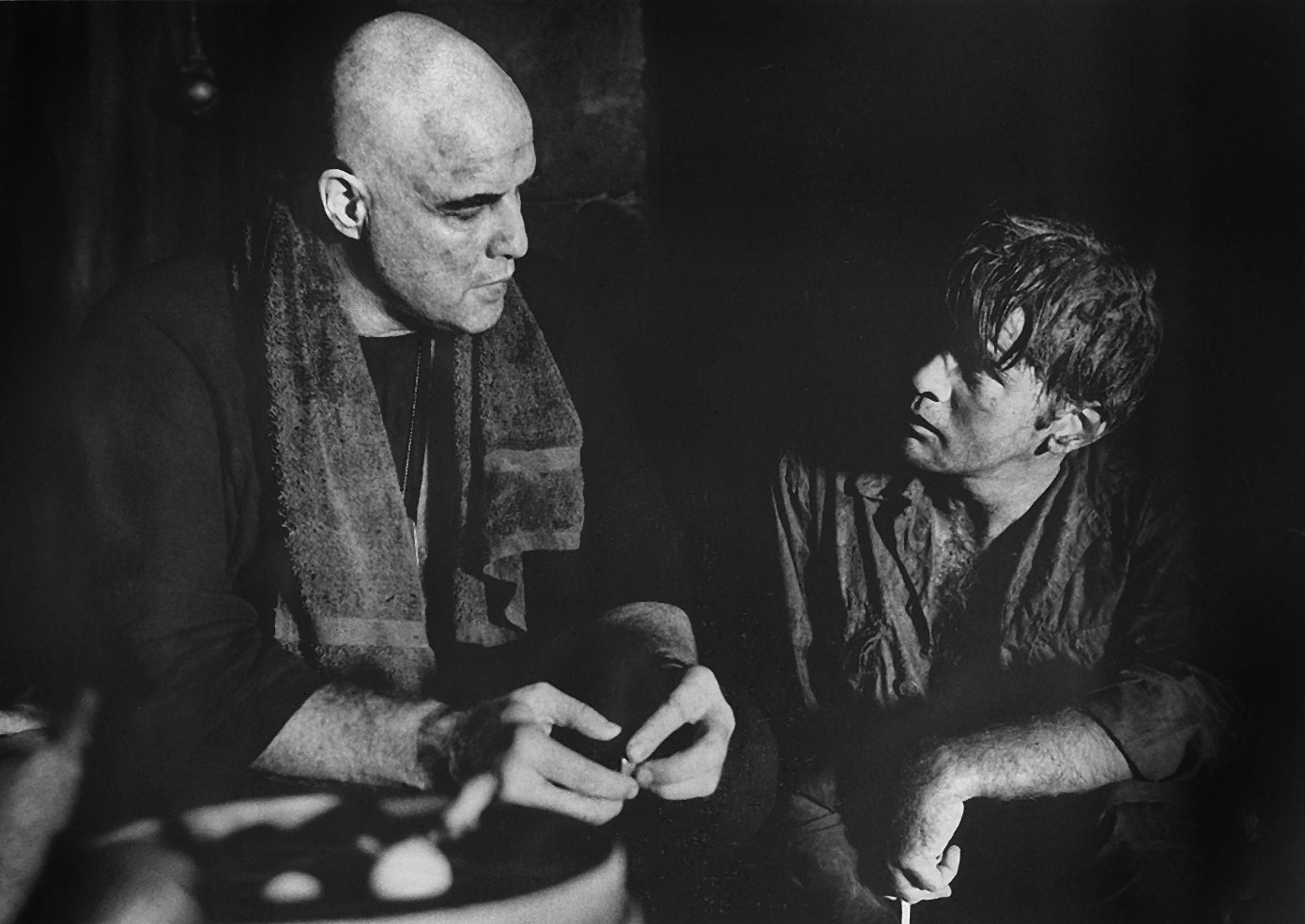

After a grueling 15-month shoot in the Philippines, Apocalypse Now was finally released on August 15, 1979. At the time, critics were sharply divided in their assessments of the film, but Francis Coppola’s visionary Vietnam War epic is now regarded as a modern classic. The film’s spectacular images earned Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC, his first Academy Award and cemented his reputation as one of the world's most brilliant and innovative cinematographers.

Storaro’s philosophical approach to the picture incorporated the careful use of deeply saturated colors, silhouettes and artificial light sources that selectively pierced the darkness of the story’s jungle settings. He further enhanced the film's dramatic look by flashing the negative. The result was an immersive experience that took viewers on a surrealistic and hallucinatory upriver journey through an array of wartime horrors.

What follows are some fascinating excerpts from a roundtable discussion held at the ASC Clubhouse, during which Storaro responded to questions posed by Stephen Burum, ASC, who supervised the second-unit cinematography on Apocalypse Now, and AC executive editor Stephen Pizzello. Also participating in the discussion were cinematographers John Bailey, ASC and Dante Spinotti, ASC, AIC, as well as AC associate editor Doug Bankston.

Stephen Pizzello: Vittorio, before I turn the floor over to Mr. Burum, I'd like to ask you how you got the assignment to shoot Apocalypse Now, which was your first collaboration with Francis Coppola.

Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC: Actually, I initially refused to shoot the picture, because I didn't want to interfere in the relationship between Francis and Gordon Willis [ASC]. They’d done such wonderful work on The Godfather films that I thought it would be wrong for someone else to shoot Apocalypse. But when I spoke with Gordon about it, he assured me that he was not a part of the project, even though there was nothing wrong between him and Francis.

Ironically enough, around the same day that [Apocalypse co-producer} Fred Roos came to Rome to speak with me about the picture, I met with Alejandro Jodorowsky; he was planning to direct Dune, and he offered me the chance to shoot it. I love Frank Herbert's book, and at that time I thought Apocalypse Now was just another war picture. To Italians in the year 1975, the topic of the Vietnam War was not that compelling, because it was so far away from us. But Francis told me, “Read Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness, because I took some of the spirit of Apocalypse from that book.” When I read it, I understood that the main theme of the story was the superimposition of one culture on top of another culture. I realized that the darkness mentioned in the book's title did not belong to the jungle culture, but to the supposedly “civilized” culture that was making its way up the river. That idea became very interesting to me, and I ultimately accepted the job.

Pizzello: Steve, can you tell us how you came to serve as second-unit cinematographer on Apocalypse?

Stephen Burum, ASC: I'd been trying to get into the union for 13 years, and I got my chance by shooting television. I'd been doing that for about two years when I got a call from Fred Roos, who told me, “Francis wanted me to ask if you'd come to the Philippines to shoot second-unit footage for Apocalypse.” I'd been reading in the papers that the production had been shut down because the terrible typhoon had destroyed the sets, but I said, “Well, sure.” I went to an office at Samuel Goldwyn to talk to Francis, and he wanted to discuss the aerial footage. When I asked him who was going to direct those scenes, he said, “You will.” I suggested that maybe [director] Carroll Ballard should supervise the scenes with me shooting them, but Francis replied, “Carol told me that you should do it.” [Laughs.]

I agreed to head up the second unit, so about a month later I got on a plane and flew to the Philippines. About a day and a half after I got there, I met Vittorio, who introduced me to Piero Servo, who would be operating the camera for me. Vittorio then said to me, “I want you to watch me shoot two scenes before you do anything.” So first, I watched Vittorio shoot [the military briefing] involving Martin Sheen, G.D. Spradlin, Harrison Ford and Jerry Ziesmer. Then I watched the filming of the picture’s opening sequence in the hotel room, when Willard is horribly drunk.

I was looking very carefully at what Vittorio was doing, because I knew I had to duplicate exactly what he was doing not only technically, but spiritually. I'd gone to school [at UCLA] with Francis, so I understood how he thought, but I didn’t yet understand how Vittorio thought, and it was very interesting to observe the way in which he used the light. Coming from the industry in Los Angeles, I was used to having all of this equipment; we had more gadgets and tools than anybody else in the world. Vittorio, on the other hand, was just using Brute arcs and Photofloods with blue gels on them. In the hotel room, he had two arcs coming in through the windows and a little cluster of lights bouncing up on the ceiling to provide a bit of fill. Then, back in this dark corner, he had a lamp on with a lampshade over it. By doing that, he made the black in the corner look better, because he had that bright reference in the frame. He also had this elaborate system of cutting pieces of paper or gels for the shades in order to block out the light coming toward the camera, and have as much of it as possible hitting the wall instead.

From watching all of this activity on the sets, I immediately understood that the color black was very important to Vittorio. About two days after watching those scenes, we started working out this big sequence set at the Do Lung Bridge. [Special-effects coordinator] Joe Lombardi was going to demonstrate those parachute flares; he was planning to shoot them into the air, for they would hang and light up a whole, huge area. Well, the flares didn't work, because the air was so humid that they wouldn't even burn. Vittorio’s solution was to really use the black areas [of the scene] and the highlights provided by the arc lights and Photofloods that we did use in the scene.

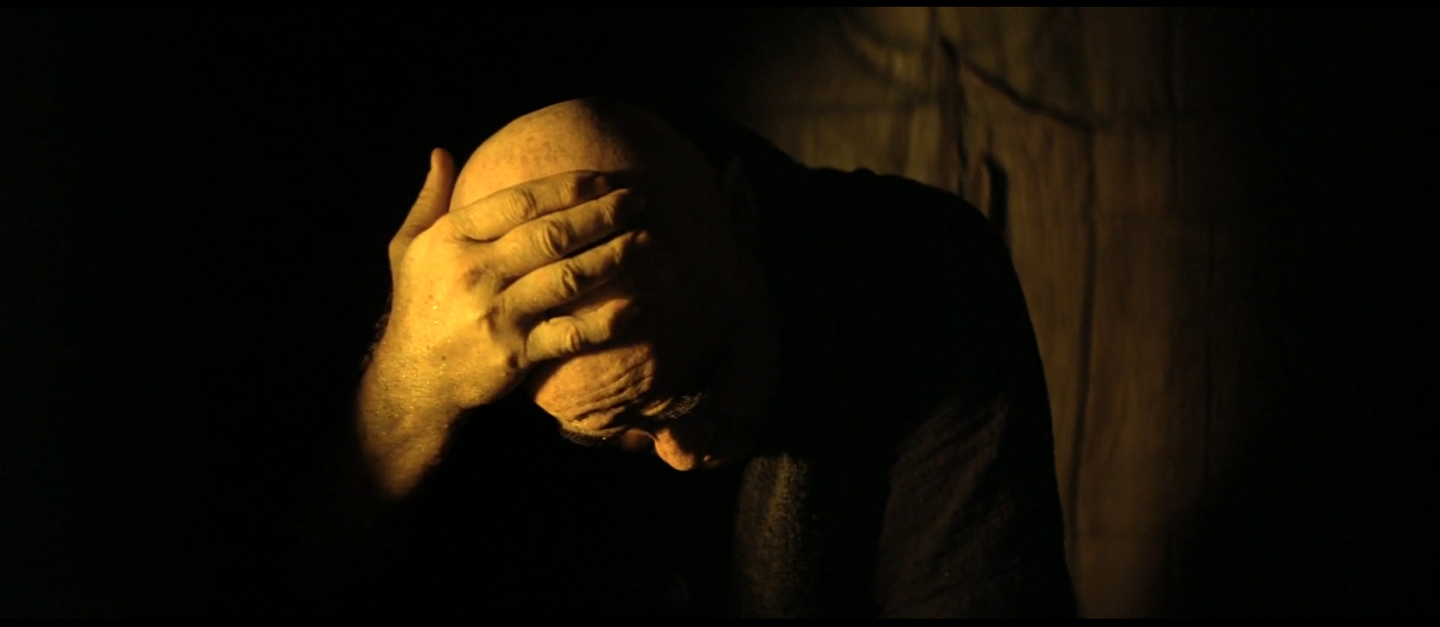

Storaro: That sequence at the Do Lung Bridge really demonstrates the main photographic concept for Apocalypse Now, which sprang directly from this idea I mentioned of one culture superimposing itself on another. Every country that has ever conquered another country — whether you're talking about Egypt, Italy, Spain, France, England or the United States — has always imposed its own language and culture upon the conquered region. Everyone from those conquering countries always believes that they're only exporting the good aspects of their culture, but that's simply not true. Everyone has a good side and a bad side — a conscious and unconscious. America was the same way in Vietnam, and in Apocalypse Now, Colonel Kurtz represents the unconscious, which we all have inside of us. He represents the dark side of the United States, which is why black is such an important color in the film. When I was planning the visual strategy for the film, I began thinking that I could convey the conflict of cultures by creating a visual conflict between artificial light and natural light. The first time I saw that we would be using colored smoke to convey specific military messages, I thought it was wonderful, because when these artificial colors were placed next to the natural colors of Vietnam, it created that sense of conflict that I wanted.

I also sought to create that type of conflict in the lighting. For example, consider the scene in which the Playboy girls put on their show in the middle of the jungle. The lighting I used for that scene came about for two reasons. First, at that point in my career, I had never used a really extensive lighting package; the biggest picture I had ever done was 1900, on which I used a single thousand-amp generator! When I arrived to do Apocalypse Now, I brought just one thousand-amp generator, without any backup — that's how crazy I was! Given the relatively low budgets that I'd had, I was accustomed to simply using the minimum lighting I required. To light that huge Playboy sequence from beyond the stage area was basically impossible, so instead I came up with the idea of using lights set up within the stage area. I asked the production designer, Dean Tavoularis, to design a set that would incorporate a number of Photofloods. However, the second reason for doing the scene that way was that I wanted to create this intrusion of artificial light in the jungle — the incredible force of the light would serve to enhance the blackness of the Jungle.

The same idea applied to the sequence at the Do Lung Bridge. When Francis showed me his idea for the scene — which involved panning from the patrol boats to the bridge, at night, on a river in the middle of the jungle — I thought to myself, “How in the world am I going to light such a huge amount of space with just one thousand-amp generator?!” My solution was to have the crew erect several towers, each of which had one arc on it. We had an electrician on each tower, and I would talk to them by walkie-talkie and tell them where to aim the light. I also remember asking Joe Lombardi to create some explosions in spots where I needed some light. But if you watch the scene, during the huge pan above the bridge, you can see only the silhouette of the two main characters against this explosion beyond them.

Burum: I find it interesting that you were able to take those technical limitations and use them to create a distinctive visual style.

Storaro: In my mind, the different scenes in the film became like parts of a puzzle. We would only show certain things amid all of the darkness, and we would reveal different pieces of the puzzle as we went further up the river.

Burum: Exactly. If you’d shown the whole jungle, it wouldn’t have been as effective.

Storaro: In Italy, we have a saying: “When the wolf is hungry, he will come out of his cave.” In other words, necessity will force you to come up with an idea! Back in those days, the Italian film industry didn’t have much money, so we did everything with very low budgets. In that regard, 1900 was really an exception; when I did The Spider’s Stratagem, we had no generator at all! On all of those pictures, I really had to work out the visual strategies with the director, because we couldn’t afford to do a master shot, an over-the-shoulder and then a close-up; that approach took too much time and money. We really had to have a good plan, because we knew we’d only have one chance to shoot each sequence. We could do multiple takes, of course, but we had to get the scenes right on the days when they were scheduled.

Burum: Don’t you think that in some ways you have more of an impact on the audience when you work with limited technical resources? You don’t have a safety net, so you have to present a vision that comes from your heart.

Storaro: No doubt. When you’re in that type of situation, you must push yourself a bit more and be very creative. You also have to think things through really carefully. Even now, when I have all of the time, money and equipment that I need, I always try to employ that type of creative approach. Sometimes, I have to fight with the director or the editor if they push me to get coverage “just in case.” In case of what? In case our plan is no good? That way of working costs the film industry a lot of money, and it drains the quality of the filmmaking.

Today, unfortunately, editors are used to working on the Avid system or something similar. They have a very small screen in front of them, and it’s very hard to see an emotion from an actor, or a particular action. On some pictures, they don’t even print dailies anymore, so editors can’t even double-check footage on the big screen to make sure that the cuts, the rhythms or the emotions are right. They work only from a small monitor, so they’re probably editing the picture with television in mind, at least subconsciously. That’s the worst thing you can do to the film industry, because you’re reducing everything to video quality. Digital technology is a great tool, but in my opinion everyone should be able to look at their footage on big video projectors, or at least a large, television-sized monitor.

Pizzello: Which camera and lenses did you use on Apocalypse Now?

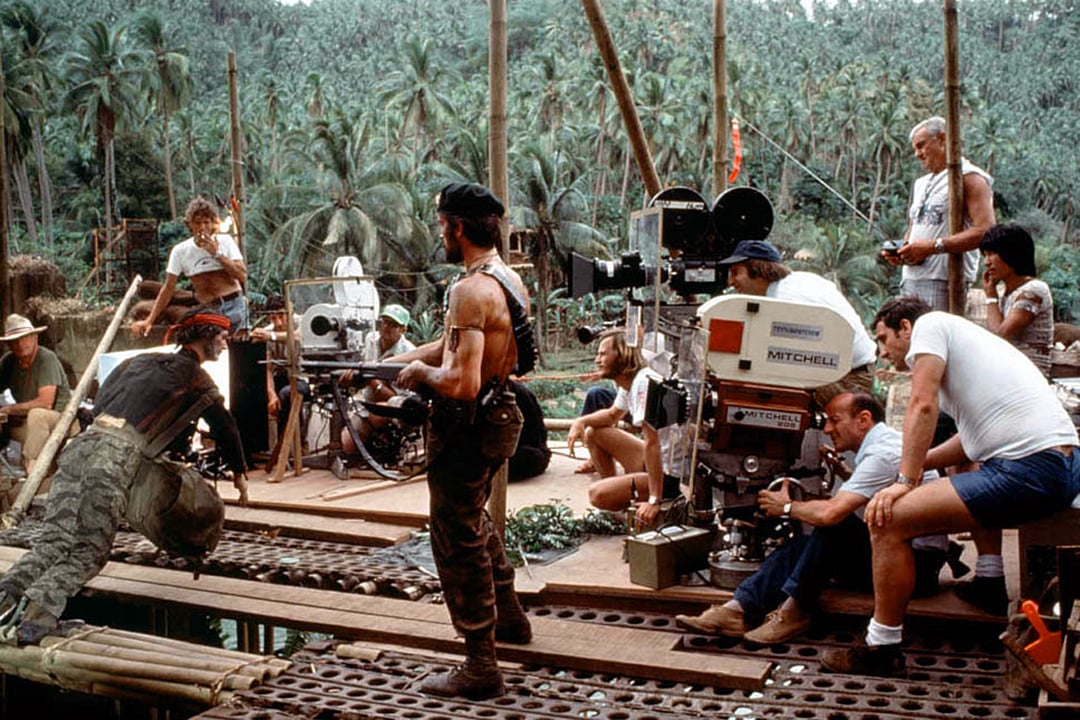

Storaro: We shot the film with Mitchell reflex cameras, which were modified by [the Italian company] Technovision to accept Cooke Hobson Taylor anamorphic lenses from England.

Because the Italian film industry was so poor at the time, we could not afford Panavision equipment, and the only serious company over there was Technovision. I developed a really strong relationship with Henryk Chroscicki, who unfortunately died last spring. No matter what I needed, he was already ready to make any changes or adjustments to the camera.

Burum: We had the most wonderful Cooke anamorphic zoom lens on Apocalypse. It converted by just unscrewing the back and screwing on the anamorphic [attachment]. It was one of the best anamorphic lenses I’ve ever seen or used, and Francis eventually bought it.

Vittorio, let’s talk a bit about the way Francis handles people, because he does it in a very interesting way. When I got to the Philippines, I went into his office, and he said, “Steve, I’m in so much trouble now that the only way we can get out of this is to do everything perfectly.” I answered, “Francis, I’ve been waiting all my life to hear someone say that to me. We’ll do it.” I walked out of that office, down those stairs, and back to my hotel, and all the way I was thinking to myself, “This is going to be great.” Then all of a sudden, I began asking myself, “What is perfect? What am I going to do?” I sometimes wound up sitting on the riverbank for three days to get a shot, because Francis had told me not to shoot anything unless it was perfect!

Storaro: On any picture, when you meet the director for the first time, you have to have a very strong connection in order to share a truly spiritual collaboration. Going back to my meeting about Dune with Alejandro Jodorowsky, I remember that the tone of it was quite cold. I knew he had a reputation for doing everything on his pictures, including the cinematography, so I asked him why he had called me. And he answered, “I know that on this movie, I need much more in terms of the operating and the lighting, and I think that you can do better.” But I couldn’t tell if he was being sincere with me or not, which made me a bit hesitant.

On a picture like Apocalypse Now, you know right away that it’s going to be a long, expensive, dangerous shoot in a location that’s very far away. But from our very first meeting, Francis was so friendly that I felt as if I’d known him forever. In the professional sense, he also made me feel totally comfortable. He told me that he had admired my work on The Conformist, and he never let me feel that I was out of place, or too young, or that I didn’t know enough English. Apocalypse became my first picture outside of Italy with a foreign production company, because prior to meeting Francis, I’d never felt comfortable with any of the other foreign directors I’d met.

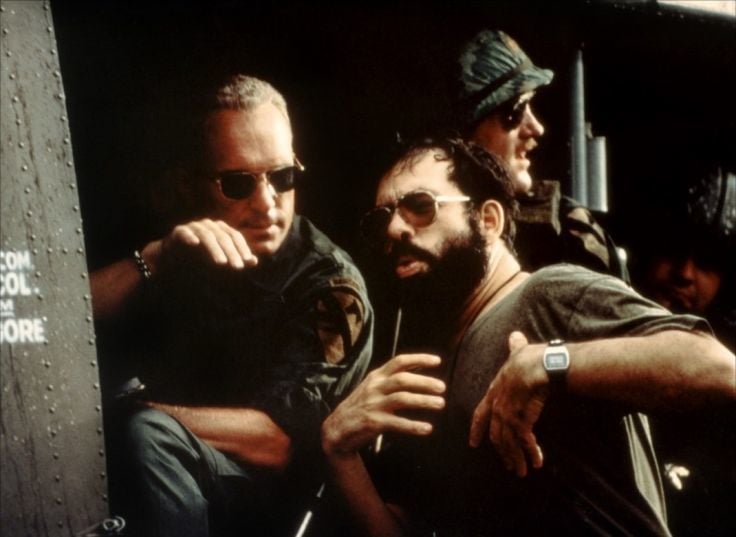

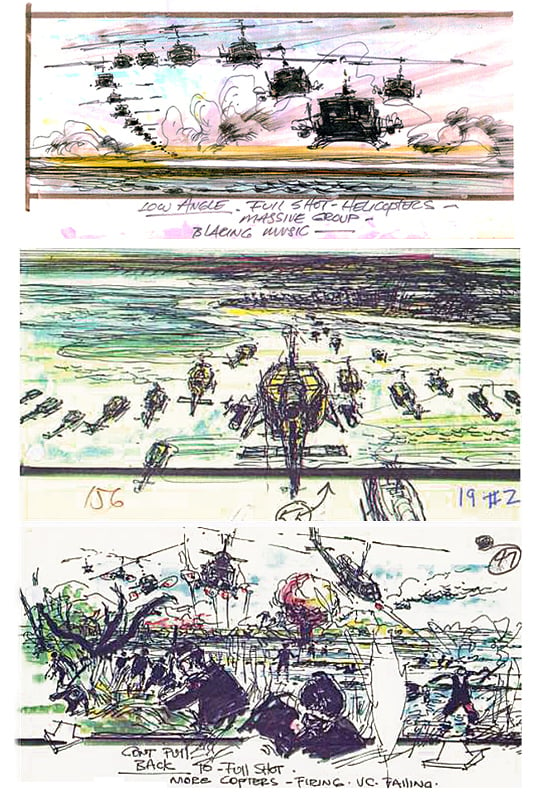

When I arrived in the Philippines, he wanted to show me some color sketches of the helicopter attack sequence — Francis had actually filmed these sketches in CinemaScope and edited them together with music, and he showed me this footage on a big screen! The camera operator, Enrico Umetelli, was sitting next to me, and Francis told us, “Remember, this is just a rough idea for the sequence; we’re going to do it much better when we really shoot it.”

I watched that footage with my mouth open, and I whispered to Enrico, “Do you think we’ll be able to do that?” I thought there was no way I could meet those expectations, but I think Francis picked up on my concern, and he was very reassuring. Without his energy, we never would have been able to make Apocalypse Now.

Burum: I do remember that when I got to the Philippines, there was a general feeling that Apocalypse was going to be a great picture. I don’t think that anybody on the crew doubted that. I don’t think anybody knew how we were going to achieve that greatness, but there was definitely a sense that we were doing the best work we could do. To me, the whole project had an aura about it.

Storaro: Honestly, I never thought it would be great, because I was so scared to be working at that level! But Francis told me, “Vittorio, this is the first picture that I’ve really produced completely. I have total control, but I also have total responsibility. I have complete trust in your expertise with the camera, so please feel free to do anything you think is correct. We don’t need any go-ahead from anybody else, but please remember that all of the responsibility is on me personally.” I always take my work very seriously, but after Francis said that to me, I really tried to give a maximum effort with the minimum equipment that I needed.

Burum: The way Francis handles everyone on a set is worth discussing. For example, when I was shooting The Outsiders and Rumble Fish, he’d show me the scene and ask, “What do you want to do?” I’d tell him, “Well, we should do this, this and this.” If he liked what I said, he’d reply, “Okay, where do you want to start?” If he didn’t like what I was saying, he’d tell me some allegorical story! [Laughs.] At that point, I’d know enough to offer him an alternative, and he’d say, “I think that’s better.” But he always made me feel that I was really contributing, and that he valued my input. That type of director really knows how to get the best out of people.

Storaro: Francis is, without a doubt, the director who gave me the most freedom to express myself. But at the same time, he was also very clear about the main concepts for the film.

The first day of any shoot is when you really begin to discover your relationship with the director, and what your contribution will be. On the first day of Apocalypse, Francis gave me an anamorphic viewfinder with my name on it, and he had one of his own. We were in this bar, preparing to shoot a scene that is no longer in the picture with Harvey Keitel, who was originally hired to play Martin Sheen’s part. We were both wandering around with these finders, and it probably looked a bit ridiculous. But he took me aside and told me his concept for that scene, and every morning after that, he would tell me his main idea for that day’s work, usually addressing things on a metaphorical level. I would then try to use my knowledge to figure out how to achieve those concepts technically. I would present my ideas, and if he didn’t think they would work, I would come up with something else. But once he was sure that I had come up with the best way to translate his concept onto film, he would give me total freedom to put together the entire sequence. He would sometimes make a few little changes to our plan while we were shooting, but usually we wouldn’t deviate much from the initial plan we had worked out in the morning.

Pizzello: What were some of your visual influences for the film?

Storaro: Just before I started Apocalypse, a very good filmmaker friend of mine wanted to do a movie about Tarzan. Unfortunately, that film was never made, but my friend showed me a book by a great illustrator named Burne Hogarth, who had drawn the Tarzan comic strip [in the 1930s and ’40s]. In 1972, just before we began working on Apocalypse, Hogarth had published two new books of his Tarzan art [Tarzan of the Apes and Jungle Tales of Tarzan], and they really focused on the principles of movement. I think Hogarth was very aware of an Italian style of painting known as Futurism, which is exemplified by the work of Giacomo Balla and Umberto Boccioni. The main aesthetic principles of Futurism are beauty and speed: Balla, for example, painted things like dogs with eight legs, in order to show their speed in one single image. A lot of comic-strip art was also influenced by studies done during the Italian Renaissance, particularly those by Michelangelo, who portrayed figures in a way that was very much like sculpture. The physical action of Tarzan in Hogarth’s art was unbelievably dynamic, and every color in the drawings was so strong and saturated that the overall impact became very surrealistic.

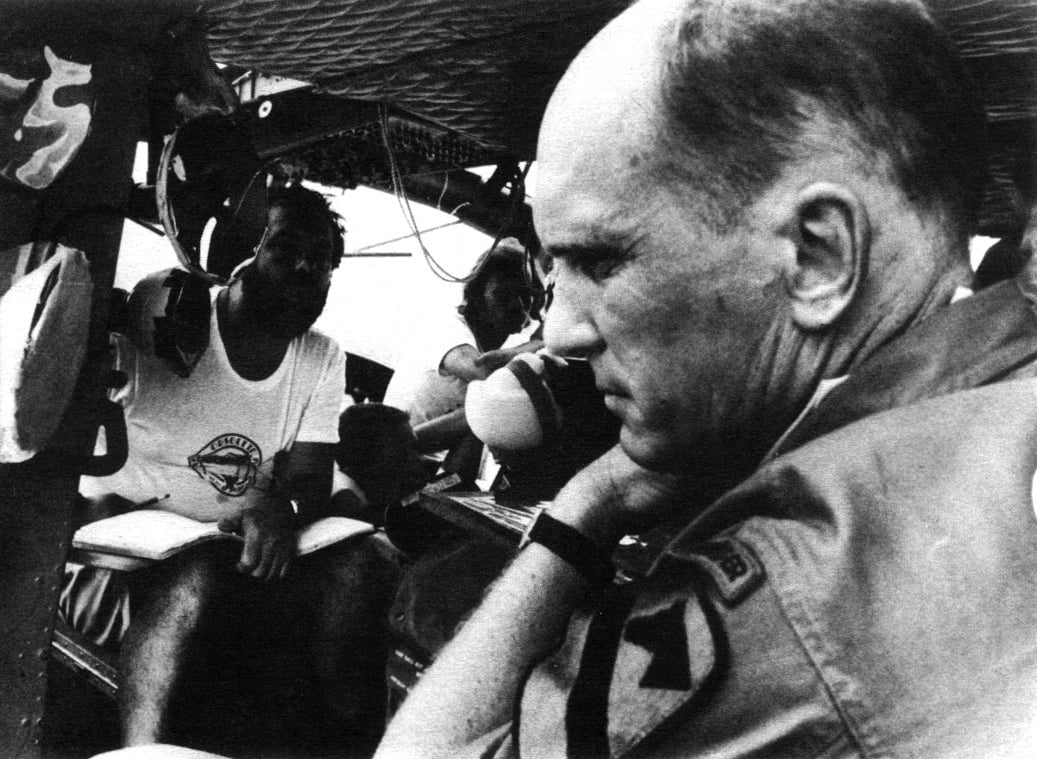

I became very fascinated with the images in Hogarth’s books, and I showed them to Francis during our early meetings. I told him that I wanted to portray the jungle in a similar way, with very aggressive colors. That style is really apparent in the sequence where the tiger jumps out at Martin Sheen and Frederic Forrest; I didn’t want the color of the jungle to be a naturalistic color. Francis and I were very much in sync on that concept; whenever he talked to me about the helicopter attack, the Do Lung Bridge sequence, or the explosion of the Kurtz compound, he would always say, “Vittorio, I don’t want to do something realistic. I want to create a big show, something that’s magnificent to see. Everywhere Americans go, they make a great show of things, and I want to create a conflict between beauty and horror.”

That approach is completely apparent in the Wagnerian helicopter attack and the subsequent scene in which Robert Duvall’s character says, “I love the smell of napalm in the morning. It smells like … victory.” It doesn’t matter to him how many people are dying; he’s somehow enchanted by the beauty of napalm. This is the point of view that Kurtz is denouncing.

Pizzello: Was your use of dramatic silhouettes in the film also inspired by comic-book art?

Storaro: Yes. In that regard, Burne Hogarth was really my guide. However, the silhouettes were also inspired by the French naive painter Henri Rousseau. He did some paintings set in the jungle that had very aggressive colors, and in one that I remember there was a man in silhouette with a woman and a tiger behind him.

Burum: While I was shooting pass-bys on the patrol boat, Vittorio said to me, “We should see nature before we see man.” I would therefore compose those shots so that the boat was hidden in silhouette, and the first thing you saw was the wake of the boat — this little silver ripple. When the ripple broke the surface of the water, it symbolized man disturbing the natural environment.

Storaro: We always strove to show the conflict between the soldiers and both the jungle and the native people. That concept is conveyed very well in the shot where Martin Sheen is in the boat examining the confidential dossier about Kurtz. Larry Fishburne is dancing to the Rolling Stones song “Satisfaction” on the radio, and Sam Bottoms is surfing behind the boat. As he’s surfing, he’s spraying water on the natives, which reinforces that idea that the Americans are imposing themselves upon this culture in a rather arrogant manner.

To me, the most important and powerful moment in the movie occurs just before the helicopter attack on the village, right after Colonel Kilgore turns on the Wagner music. We suddenly cut to a quiet shot of a teacher leading this group of children out of their school, and as a viewer you say to yourself, “Oh my God, are they going to attack those little children?” In most previous war movies, you always saw the cavalry arriving to save the day by attacking the bad guys.

Pizzello: Let’s talk a bit about the explosion of the Kurtz compound, which was only shown over the end credits of the initial 35mm release prints. That footage never appeared in the 70mm prints, and Mr. Coppola has acknowledged that its inclusion in the 35mm credits caused some confusion about the film’s ending.

Burum: Everybody tried to make a big deal out of that footage, but the only reason Francis included it in the 35mm prints was because Joe Lombardi got really upset when it was removed from the original cut. Francis arranged this work-in-progress screening for the cast and crew at the Bruin Theater in Westwood, and when it was over, Joe grabbed Francis in the lobby and jumped all over him: “Damnit, I had my effects guys all over the jungle to shoot that scene!” So in order to placate Joe, Francis put the footage over the credits, which led to all of this speculation about the film’s ending.

Of course, that footage was definitely a challenge to shoot. What do you remember about working on that sequence, Vittorio?

Storaro: It took nine nights to shoot that scene, and we set up about 10 cameras — a VistaVision camera, an infrared camera, a high-speed camera and normal cameras. Before we began shooting, I had constant nightmares that someone was going to get hurt. I kept asking Joe where we should put the crew members and the cameras to keep them safe, and at first, he couldn’t say for sure — the temple was built out of real stone, and he was planning to use real dynamite to blow it all up! He finally gave us the minimum distances where we’d be safe from the explosions, and we also built these moveable metal bunkers to protect the cameras and the operators. When the explosions went off, all of these big stone blocks were flying around, so you couldn’t even look through the camera.

Pizzello: Why was the temple set built with real stone?

Storaro: Dean Tavoularis wanted it to look authentic, of course, but I think it was simply easier to use real materials in that particular location rather than shipping materials in.

Burum: That temple was well-built, too. When we first attempted those shots, it simply wouldn’t go down! Finally, we attached these cables to both heavy-duty tractors and the set, and when the explosion happened we just pulled the temple down.

I’ll tell you, when those explosions went off, they were so powerful they would lift you right off the ground. All of the air would be sucked away from you, and then this rush of hot air would come back at you. Joe also warned us, “Keep under cover, because once the blast goes off it’s gonna be raining snakes.” And it was! [Laughter all around.]

Storaro: In the end, not one person was hurt, which was a real testament to Joe and his crew. They kept everybody informed about what was going to happen every step of the way. All of the camera operators and effects guys were communicating with walkie-talkies, and I can still remember hearing the explosions going off in my ears.

Burum: Vittorio, can you tell us about the lab work and the special processes used on Apocalypse Now?

Storaro: Well, I had several problems in that regard. For the first two weeks of shooting, the dailies were being sent to Technicolor Rome, which was just what I wanted. But then Gray Frederickson, the co-producer, said to me, “We only have one airplane a week that can go to Rome, but we have two or three that can go to Los Angeles, so we’re going to have to do the dailies at Technicolor L.A. from now on. Who do you want to deal with there?” Francis was very nervous, because he wanted to see dailies sooner than one week afterwards. But I told Gray, “Well, tell me who your next cinematographer is going to be, because I’m leaving. How can I have the same collaboration with the people at the lab [in Los Angeles] if I don’t know anybody there? They don’t know me, and they won’t know what to do.” Ernesto Novelli [of Technicolor Rome] had done The Spider’s Stratagem [1970], The Conformist [1971], Last Tango in Paris [1973], 1900 [1977] and several other pictures with me, so he knew exactly what kind of look I wanted. Fortunately, after I threatened to leave, they continued to let me send the dailies to Rome.

Also, around that time, Kodak had just introduced its new color negative stock [5247]. I did some tests with the new stock for 1900, but I didn’t really like it. When I did Scandal [1976] just before Apocalypse Now, Kodak Italy told me, “You have to use the new stock, because there’s none of the old stock left.” I therefore refused to buy the film in Rome, and we called Kodak in Rochester, New York. They had enough of the previous stock for us, so we bought it from them instead for Scandal. By the time I was doing Apocalypse, there was no way I could use the older stock again, because the [change to the new stock] was almost complete. I wasn’t happy with the contrast of the new stock, and when I did some tests in Rome with Ernesto Novelli, we decided to flash the negative of Apocalypse Now. After exposing the negative, we would sent it to Rome, where they would flash it before developing. Frankly, I don’t know how many other producers or directors would have allowed me to do something like that — Francis gave me his complete support.

After I came back from the Apocalypse shoot, we did the first timing of the film in Los Angeles with Ernesto Novelli and Larry Rovetti supervising the work. Later, in Rome, I told Ernesto that I was unhappy with the blacks in the film, because black was one of the most important colors in terms of the visual strategy. Black represented the unconscious, particularly in the sequences where we discover the true meaning of Kurtz; we were trying to show some portions of the truth emerging from the depths of the unconscious. Those scenes were designed to come together like the final pieces of the puzzle, we had created, and if the blacks weren’t black enough, that aspect of the story would not make as strong an impact visually.

When I told Ernesto I wasn’t happy with the blacks, he reminded me of an incident that had occurred several years earlier, during the filming of 1900. On that picture, we had used an original matrix dye-transfer system was the only way I could accomplish that strategy, and it looked wonderful. At one point, we were shooting in Parma, Italy, and every day we were sending dailies to Ernesto in Rome; occasionally, he would visit me on the set so we could discuss things. One day he came to me with a roll of film, and he said that it had been treated with a new process that he’d invented. I told him I didn’t want to see it, though, because I had settled on my approach for 1900 and I felt that this new process would distract me.

Well, later on, when I was having my problems with the blacks on Apocalypse, he finally showed me an example of this new process he had developed. He had me look at some images from Cadavari eccellenti [1976, a.k.a. The Context or The Illustrious Corpses], a film directed by Francesco Rosi and shot by Pasqualino De Santis. The movie was a crime thriller that required strong blacks and a very dramatic look, so Rosi and De Santis used Ernesto’s new system for all of the dailies; unfortunately, for the usual distribution reasons, they didn’t use the system on the release prints — they only used it for the dailies. It looked great, so I performed some tests during [the postproduction of] Apocalypse Now, and the dense blacks we got were exactly what I’d had in mind for the scenes with Kurtz. That process, of course, was what came to be known as ENR [in honor of its inventor, whose full name is Ernesto Novelli-Raimond]. While I couldn’t apply ENR to the first release prints of Apocalypse, I later used the process on Reds [1981].

Pizzello: What can you tell us about the current restoration of Apocalypse Now for theatrical re-release?

Storaro: This new version is being supervised by the film’s sound editor, Walter Murch, and it will have 55 minutes of footage that was cut from the original picture.

Burum: I’ll be glad to see that footage back in the film — especially the key sequence in which the soldiers get off the boat and stumble across a French plantation, where they have dinner with the people who live there. I was so ticked off when that was cut out of the picture, because it really addressed the central philosophical concept that Vittorio mentioned earlier — one culture imposing itself upon another. During the dinner, the French tell the Americans, “We’re not afraid of the Vietcong. These are our people.” A big philosophical discussion ensues, during which the French essentially denounce the Americans as colonialists.

Storaro: I think that scene was cut because of the line in the script that says, “Never get out of the boat.” When the men do get out of the patrol boat, they run into trouble, and after the scene with the tiger, Francis wanted them to stay on the boat. In my experience, that’s still a very good piece of advice! [Hearty laughter around the table.]

This article was originally published in the February 2001 issue of AC.

Apocalypse Now was selected as one of the ASC 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.