Behind the Scenes of The Deer Hunter

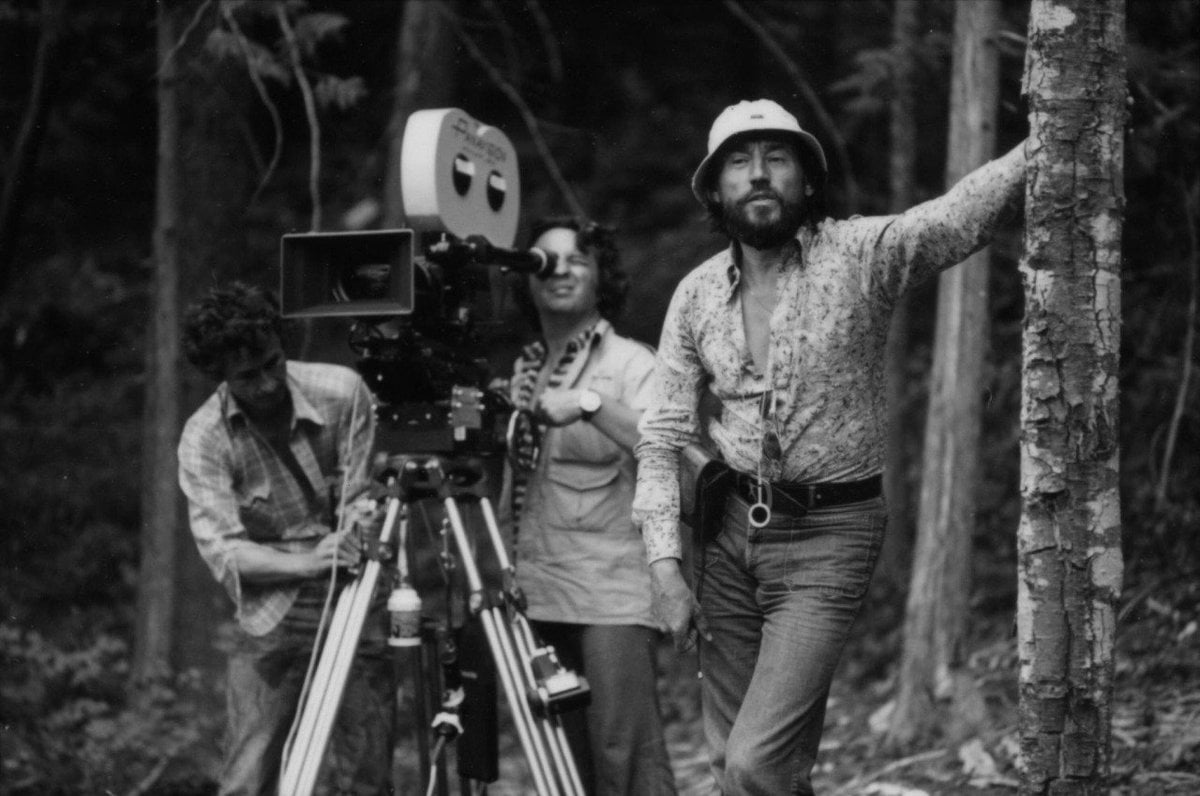

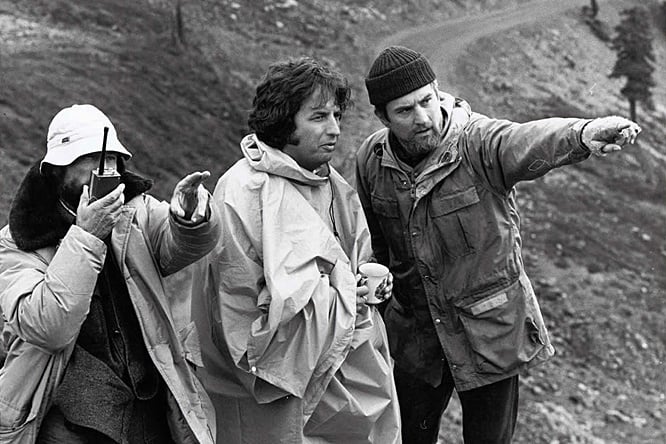

The challenge included shooting inside a cramped trailer, an immense cathedral, a steel mill, the icy slopes of Mt. Baker, the jam-packed streets of Bangkok and a raging river with water up to the matte box.

One of my biggest problems in photographing The Deer Hunter was trying to get a cold, rainy, autumn look for the steel mill areas around Pittsburgh — while shooting in the middle of a very hot summer. We had hoped to find locations where there were no trees or vegetation, but unfortunately there were lots of trees and grassy areas in the Ohio River Valley locales where we had to shoot. The only solution was to defoliate the trees and change the color of the grass — which we were able to do, thanks to the skill of a terrific greens man and special effects expert. They sprayed the grass with certain chemicals and two weeks later it turned “California brown;” I couldn’t believe it.

The trees were more difficult, because the leaves actually had to be stripped off of them, and we were afraid that the trees might die. For example, surrounding the cathedral in Cleveland where the wedding in the film takes place there were many trees that had to be defoliated and we were afraid the leaves would never come back. Later, when we were shooting in Thailand, we got a letter from the priest, who wrote, “Don’t worry. The leaves are on the trees again.” That made us feel very, very good.

Besides taking the green out of the landscape, we also tried to enhance the autumn feeling by wetting the streets down all the time. That helped a lot to create a cold feeling, especially when the sun was not out. However, since we couldn’t depend upon overcast weather all the time, we had to shoot many scenes when the sun was not yet up or when it had already gone down. Printing those exterior scenes toward the blue side later helped give them a cold look. By way of contrast, we printed the interiors warm.

I didn’t do any of that color modification in the camera — like using coral or 85 filters on the lens — because there were times when I needed all the exposure I could get. I always believe in getting the maximum amount of light onto the film, because that gives me the opportunity to use smaller lighting units and a better f-stop for achieving a greater depth of field. I always rely on the lab when I have certain color effects in mind and I talk it over with their technicians in advance so that our dailies will be printed that way. My friend Skip Nicholson at Technicolor did a marvelous job in helping me get the right colors all the way through the picture.

As I've said, we used blue to create a cold exterior feeling and warm brownish tones inside. But when we had windows or open doorways in an interior shot, we made an attempt to actually mix the two colors by mixing light, so that the exterior background visible through the windows looked bluer than the inside. We didn’t use 85 gels on the windows, as we usually do, but we still got the look that we wanted. This technique proved to be a simpler way of handling the situation — and a lot less work. I hate getting the windows anyway, because I can always detect the reflection in the gels. Even when you are using the good heavy plastic sheet, double reflections make it obvious that there are gels on the windows. I try to avoid them as much as I can. I’d rather use the mixed color light technique nowadays.

Inside the trailer (which is where the character played by Robert De Niro was supposedly living) the temperature was always well over 100°F — and the actors were wearing winter clothing. They would start to sweat immediately and our biggest problem was to keep the perspiration from showing in the closeups. My operator had to watch that very carefully through the lens and we had to repeat shots quite often because of it. We didn’t have an air-conditioner for the first few days, and when we got one, it didn’t work. That caused some delays in shooting and they finally had to ship in a very large air-conditioner to get the temperature down to a more comfortable 85°F.

I didn’t use much diffusion on this picture — in fact, I don’t recall using any at all — because we wanted to make the images look very sharp. On the other hand, I used the zoom lens a lot, which gives you a little softer rendition of faces, and I used regular soft lighting, especially in the closeups. For the exteriors we used overcast a lot, which by its very nature produces a nice soft look. But this in combination with sharp lenses minus diffusion added up to a realistic result.

I purposely did not want the “poetic” look that I had become known for in some of my earlier films — especially since we would be filming Vietnam war sequences that had to have a harshly realist documentary feeling. I didn’t want to end up making two different films at the same time. Therefore, I knew there would have to be some kind of visual connection between the American and Vietnam segments of the picture. Avoiding the use of diffusion helped in that respect.

As far as lighting was concerned, I used the same basic techniques that I always use — namely, trying to make the lighting look as realistic as possible. I really believe that light should appear to be coming from a realistic source. In a daylight interior scene, it should appear to be coming from practical fixtures in the set. I always make an effort to confer with the art director when he is designing the sets so that he will give me enough light sources to play with. It makes the cameraman’s life much easier when the art director establishes nice light sources for him, so that he can shoot in any direction and justify a key light or a kicker or a backlight. I like to use lighting to create a mood and that’s much easier to do when you have visible light sources working for you.

Speaking of lighting, the steel mill sequence presented quite a challenge, because when the flowing melted steel comes from the furnace it emits a tremendous amount of light. The problem was mainly one of balance, because we didn’t want our actors to go completely into silhouette. We wanted the audience to be able to recognize Robert De Niro and the others as actually being in the scenes — which they were at least half the time, although we used real steelworkers in the long background shots.

This meant that we had to add light supposedly coming from other sources, such as practical light bulbs and the outdoors. We used 9-unit FAY lights with 3200°K globes to bring the level up to 400 or 500 footcandles for shooting at about f/8. For the background, since those furnace sheds are open on the sides, we tried to shoot against real daylight. Of course, since we were shooting primarily for the inside look, the outside went slightly toward the blue, which was very nice because that sequence followed an earlier dawn sequence that had been given a rather bluish cast to simulate a winter sunrise effect.

While it looked as though there was a lot of daylight coming through in the background, we actually had to supplement it through the use of several 2500-watt HMI lights. We used these relatively small daylight sources mainly for convenience. Because all of the equipment had to brought up on ladders or small elevators, we couldn’t use Brutes or any other huge, heavy equipment. Also, we could plug the HMI lights into existing electrical circuits — which was a great help, because we couldn’t even get our generator in there.

As I mentioned before, the balancing of the light was the main problem in the steel mill, because when you aim the camera at flowing molten steel, you are really talking about photographing the sun. It is so hot that you really can’t get an exposure for it, so all you can hope for is to get interesting compositions of the flowing steel and let it glow a bit on the film. The reason we needed so many footcandles of added light was to be able to stop the lens down so that the steep would not burn up and appear white. We wanted a flaming orange color and we tried to keep the lighting key high enough throughout the sequence to maintain that color consistently. For the same reason, we used 3200°K lights to key our people and the 85 filter on the lens also added a built-in orange quality. For filming the actors in that sequence we used half MT-2 gels on the lights to get an even warmer glow and added a flicker effect so that the light would appear to be coming from the flowing “lava” of the molten steel.

In the street mill (and later when shooting in Thailand) we were afraid that the intense heat (up to 180 degrees inside the mill) might damage the film, but nothing at all detrimental happened to it. The results were just beautiful, so it would seem that the 5247 film is probably insensitive to heat.

We shot in eight different towns and it was essential to have the steel mill in the background as much as possible, since it was important to the story to show our characters playing against the town they were living in. This presented some special problems in staging the night sequences. If we had shot them night-for-night, a tremendous amount of light would have been needed to illuminate those mills in the background. Besides, the mill authorities didn’t want us to do that. They had been having a lot of trouble with the government about polluting the atmosphere and they didn’t want us to film smoke coming out of the smokestacks, even though the period was supposed to be 1968. They were not about to cooperate with us in any way.

As a result, we had to sort of “steal” those scenes. We knew from the beginning that we would have had to light from the street far away in order to reach those smokestacks — which would have been impossible. As an alternative, I decided to shoot the key long shots at the “magic hour,” just after sunset but before complete darkness fell. In this way, the structure of the steel mill would be silhouetted against the sky to pick up the outline and the remaining slight glow would highlight the details a bit. That’s how we shot the opening sequence when the truck rolls out onto the highway, and that’s how we shot the scene after the wedding, when they are running down the hill and you see the steel mill in the background.

One can rightly question to what extent those scenes actually look like night — and to tell the truth, I questioned it myself — but now when I look at the film, I realize that sometimes you have to depart from reality in order to create the feeling of reality. The scenes I'm talking about look different from the way they would look if they had actually been shot at night — but somehow it works, and I think that’s why art differs from nature.

Speaking of the lack of cooperation from the steel mills, I must say in all fairness that the one where we shot the interiors was extremely cooperative. The people there liked our story and didn’t mind our shooting inside. They even taught our actors how to do the various operations and let them actually work in the scenes.

The wedding sequence filmed in St. Theodosius Cathedral in Cleveland presented a really great challenge, not only because it was so big, but because it was very beautiful and we wanted to make it look that beautiful on film, also. So we took great care and spent a whole day just rigging the lights inside, which included hiding light units behind columns and wherever else we could.

Again we used the technique of mixing the bluish outside light coming through the stained glass windows with the warm light motivated as a source by the chandeliers of the cathedral interior. The use of 3200°K light inside, especially when contrasted with the outside blue, gave us the golden tones on the faces and golden hair lights which I loved in that sequence and which seemed to be so appropriate to the mood.

The wedding reception, which was actually a huge dancing party, presented a difficult lighting challenge, because the only hall that size we could find in Cleveland had a very low ceiling. In the long shots we were shooting from outside in the hallway to show the entire room — ceilings included. The only solution was to hang a lot of banners from the ceiling, like decorations, and these served the purpose of hiding our lights. They also made it possible to use a lot of cross light for modeling. I would have hated to use flat light in that sequence, because the beautiful kicker lights on the faces really made them come alive.

When mixing bluish outdoor light coming through windows with 3200°K light inside, we found the new HMI lights to be very handy. We didn’t have to filter them or gel the windows. We would simply turn on a 4000-watt HMI unit and shine it through a window or doorway and it would give us almost as much light as a Brute — without the hassle that goes with Brutes. This was especially important because we didn’t have a big crew — only about four electricians. The HMI units are really super lights. Their color temperature never changes and they are very lightweight and flexible. We could hang them up high if we wanted to, or simply mount them on Molevators and raise them 10 or 15 feet. They didn’t give us any flicker problem at all, because we had a good generator that stayed precisely on 60 cycles, which is very important. Also, of course, the Panavision camera, with its 200-degree shutter, helped a lot to eliminate the flicker problem.

In addition to the HMI units, which represent the latest in film lighting technology, we used a lot of “old-fashioned” lights. My gaffer, Rick Martens, loves the old Masterlights — the very old booster units that are used with Colortran converters. He would simply plug a 500-watt unit into the transformer and boost it up to the light equivalent of a 2000-watt unit.

Rick finds these lights to be very handy and he’s very skilled in using them. He usually has a second generator somewhere, like a half-mile away, and he can light up two city blocks at night with just Masterlights and maybe a couple of HMIs to scratch the walls. We found that we could operate very fast with this combination of old and new lighting technology, leaving as much time as possible for the actors and director to get the performances. Since The Deer Hunter relies very heavily on dramatics and character development, we realized from the beginning that we would have to give the actors lots of time and not spend it all in lighting.

Shooting inside the cramped quarters of the trailer could have been extremely difficult for us, but we made our job much easier by building the trailer right on the location. We actually bought a trailer and cut it in halves and constructed wild walls that could be moved out. In the center of the living room there was a sort of A-shaped ceiling piece that was wild. We could take it down and cover the opening with diffusion material, which gave us a nice overhead soft light on overcast days. We used this beautiful soft light for fill and added our key lights to it, maintaining quite a consistent quality of lighting all day long in this way. Actually, this technique is a very old-fashioned one, since the earlier movie studios in Hollywood had open ceiling and curtains that could be moved back and forth to control the lighting.

The diffusion medium we used is made by 3M and is a kind of “shower curtain” material. For some reason, we called it “velveteen,” although it is not at all like velvet. I don’t know where that name comes from, but other people call it by different names.

Even when we were shooting night interiors inside the trailer we had to take the ceiling off, because we had to have someplace to rig our lights. We would put our lights up and then, three or four feet above them, tent the whole ceiling with black material to keep out any stray light. Even though it was very hot inside the trailer during the day, we often shot day-for-night in there for several reasons. First of all, most people don’t like to work a lot at night. Then you have the turn-around problem, which means losing a day in the schedule. This can get very expensive, and since today’s productions are very economy conscious, you have to save as much time as possible. That’s why we decided to shoot certain scenes day-for-night inside the trailer — which didn’t make our lives any easier. It meant that if a doorway was to open during the course of the action, we would have to tent off 10 or 15 feet of the exterior and light some kind of object out there to create a feeling of depth. We couldn’t just shoot against black velvet, because the effect would have been completely unrealistic.

We had a lot of fun with the night exteriors, actually, because we had some big scenes to light — several of them extending to two blocks in length. My gaffer just loves challenges like that, and his technique of using the Masterlights and HMIs to cross light the houses in the distance looked very good, especially when we had haze in the middle of the night. Part of this came from the smoke of the steel mills, and then we would often get fog rolling in about four o’clock in the morning. That gave us a glow in the distance, which I liked very much. It created a texture in the sky and behind the buildings of a type which is very, very rare and difficult to get onto film. It’s impossible to simulate on a studio backlot, and when it happens on location, it’s just gorgeous.

We shot in the anamorphic format — which was essential to the vast scope of this picture — and used Panavision equipment all the way through the filming. We had one Panavision PSR, which I used as the “Number One” camera because I like its viewing system very much. It gives you a very bright image and makes it possible to judge composition and focus much more precisely than with the current Panaflex model. But, of course, when you are shooting a lot on location and are pushing through narrow corridors where it is impossible to use the straight viewfinder of the PSR, you really have to use the Panaflex. I like the Panaflex very much, but on The Deer Hunter I still used the PSR whenever I could because of the viewing system.

On the picture that I just finished shooting, The Rose, I used the Panaflex-X, which is similar to the Panaflex, except that it has a fantastic viewing system that is twice as bright as that of the PSR, so now I am convinced that I will never use the PSR again. There’s no reason for it. I will use either the Panaflex-X or the Panaflex, when a rotating viewing system is needed. However, Robert Gottschalk says that the standard Panaflexes will be modified within the next few months to include the new bright viewing system, so we’ll be in good shape.

In our preliminary discussions of the Vietnam war segment of The Deer Hunter, we decided that we wanted to make it visually different from anything else in the picture. We even wanted to make it look like it was shot with a different kind of film stock. The new 5247 color negative is so good and so sharp that if I hadn’t done something to alter its characteristics, it would have looked just too good. What I actually wanted was for the scenes to be shot in Thailand (simulating Vietnam) to look like war or documentary footage.

I discussed this with Skip Nicholson at Technicolor and said, “I want to try something and i’ll need your help with it. I’m going to underexpose the film three stops and have you overdevelop it three stops.”

He said that he would (and I should) feel safer if I would underexpose only two full stops and have him overdevelop two stops, in order to get a heavier negative and build some grain into the footage. Well, I must say that we really tried to ruin the 5247 to the point where it shouldn’t have looked like anything, but the film is so incredibly good that we couldn’t destroy its quality. You can monkey around with and do everything to degrade it, and you can still bring it back to look like you didn’t do anything to it.

Finally, in desperation, we had to go to second generation printing in many cases in order to bring in more grain and make it look like documentary footage. About 35 percent of the war footage in the picture is a second-generation print, which meant that we had to make a dupe negative, destroying it as much as we could with underexposure and overdevelopment so that the dupe would look crummier. That’s how we finally managed to inject a documentary quality into those sequences. If you really study that footage you can see the difference. It’s grainier; it doesn’t have much shadow detail; it looks older; it looks as if we used some bad film. In a war situation they usually don’t keep the film under the right conditions of temperature and humidity. Sometimes it sits around in the sun for weeks and all that.

The majority of the shooting in Thailand took place on the River Kwai in an area that was as remote as it could be. We read a brochure which said that it was the least populated area in the world. It was right in the middle of the jungle, alongside the river, and the local people said that it was very dangerous to work there because there was a lot of smuggling traffic going through to Burma. The Thai government gave Michael Cimino and Robert De Niro special bodyguards and they weren’t allowed to take one step without those guards next to them. Even when we went to a remote restaurant in the Floating Village, we had guards in our van, and many times they would stop in the middle of the road in the dark night and examine something on the roadside that looked suspicious to them. It was quite scary, but nothing actually happened to us. Either we were lucky or they just wanted to make a big deal about the security.

The River Kwai is quite a river. Its height changes according to the weather and since we were working in the rainy season, its level could vary 10 or 20 feet overnight. The script originally called for a native hut to be built right alongside the water, but we gave that up because it would have been washed away if the river rose, or it would have been up too high for us if the river was low. So we decided to build a hut that looked like it was on poles at the edge of the river, but actually it was floating. It was engineered by our art director with air tanks underneath, but in order to balance it we had to use a lot of sandbags. For example, if we had to use a lot of sandbags. For example, if we had the camera, the dolly and a lot of people on one side of the hut during shooting of a scene, the hut would be floating off-level, so we would have to pile sandbags on the other side. We had to do this before making every shot and it became a nightmare. Of course, we eventually discovered that in certain shots the camera couldn’t tell whether we were level or not, so we ended up shooting a lot of scenes off-level when it didn’t matter.

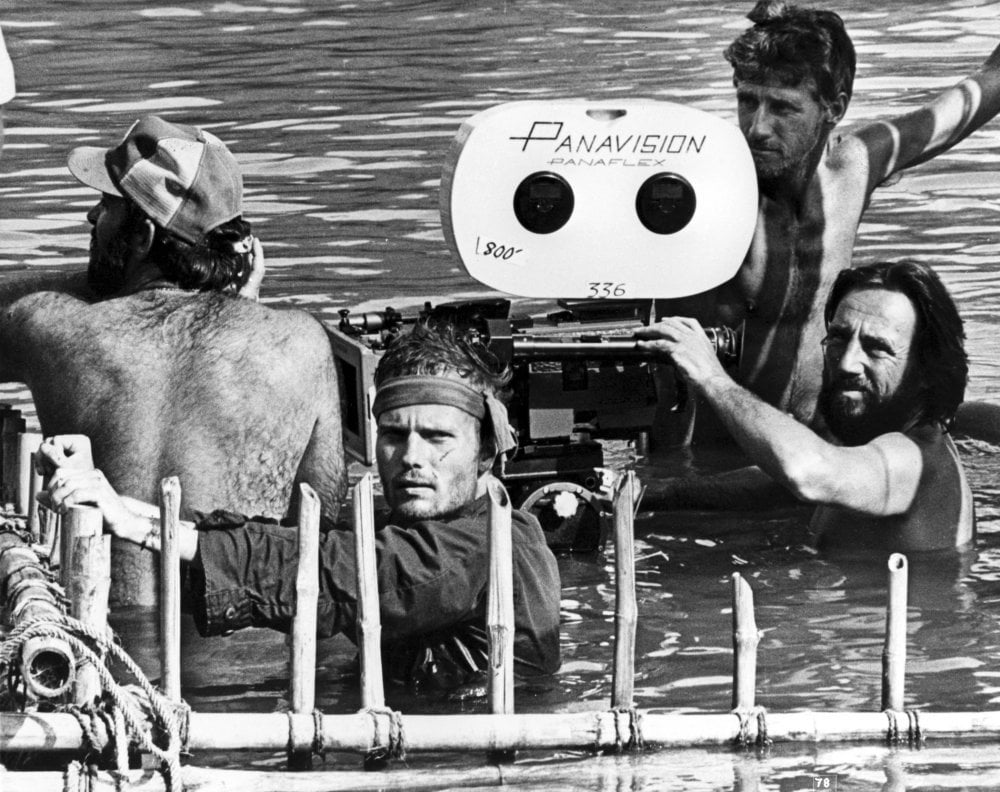

The hut was about 15 feet wide and 18 feet long, but it had to accommodate at least eight or ten actors, the camera crew, the special effects people and everybody else, the dolly and sometimes two cameras, so it was quite crowded. When we were working under the hut where the prisoners of war were hanging from ropes, it was really uncomfortable, because we were standing neck-high in the water. But that’s where the Panaflex came in handy. We could put it just under the roof, but just above the water level, and we couldn’t have shot it any other way, unless we had been willing to give up the idea of shooting sync sound. We shot everything with sound and many, many times the water rose to just barely the matte box level of the camera — which gave it an interesting look.

Of course, the balancing of light under there was really a problem, too, what with having to run the cables through the water. We couldn’t use the HMI lights there because we didn’t have a generator that we could depend on to hold 60 cycles precisely, so we had to use Brutes. We built a floating deck to hold two Brutes and that gave us our key light for shooting on the upper level. For shooting on the lower level, we bounced the light off the water and that created an interesting ripple effect. We used some Masterlights with dichroic filters for closer shots and we tried to keep the lighting low key since it was naturally dark under the hut.

The hut was built by us and the roof was made of bamboo, which meant that we could tear it apart if we wanted to — and we did so many times. It was the same technique that we had used in the trailer back in the States. We used some diffusion material on top, which gave us an overall nice soft lighting, and we used the Brutes for key light coming through the bamboo panels on the sides. This gave us an interesting lighting effect, which we kept pretty consistent all the way through that horrible sequence in which the Viet Cong are playing forced Russian roulette with prisoners of war.

It was quite a job to hoist the Fisher dolly up into the hut, because it first had to be taken across a bamboo bridge that was floating on the river. At one point the dolly actually took a dive into the river and it took about 14 people to get it back onto the bridge. Luckily we had lots of people to help us.

The Fisher dolly was essential because we had to make many moves during the hut sequence, including up and down moves, and we didn’t want to sacrifice that. Since we were using the anamorphic format, such vertical movement became very important in order to keep the composition critical in relation to the lens height, and also to compensate for movement of the actors within the frame.

Many of our shots — for example, the establishing scene of the hut — were shot from a motorboat. We balanced the camera in front, gave speed to the boat with the motor running, and then shut it off in order to get a smooth ride without the vibration of the motor. We just coasted down the river approaching the hut and that gave a fluid look to the establishing shot,.

The same boat-mounted camera was used for the escape sequence, when the two men get away from the hut and start floating down the river on a log. The whole sequence was shot from the motorboat, which meant that not many crew people could go with us. We actually had two boats which carried the director, the operator, myself, one assistant, the script supervisor, the assistant director and two sound people. The experience reminded me of the filming of Deliverance. The river was very pretty and we had a lot of fun shooting that sequence.

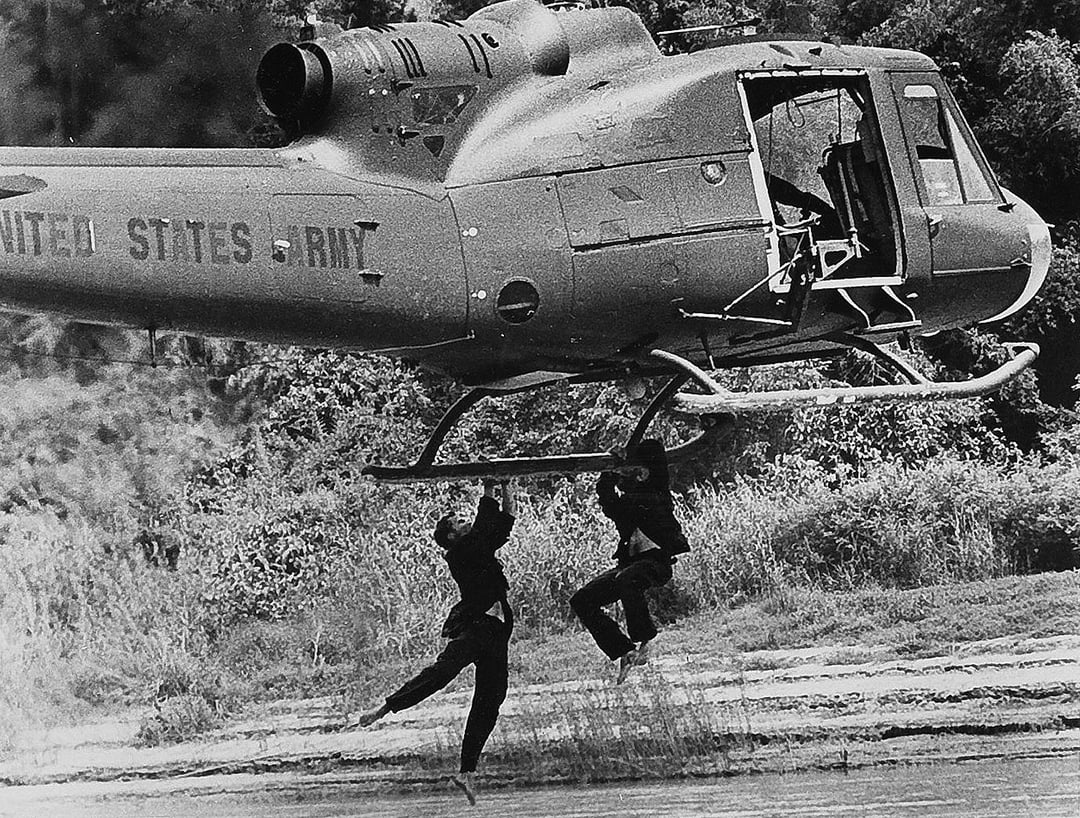

The helicopter scenes were very difficult to shoot because we didn’t have helicopter pilots who were trained for motion picture work; they were just regular pilots.

We also had communication problems because they didn’t speak good English. We had to go through interpreters and use hand signals and it was necessary to have many rehearsals before we could shoot.

Since we were so far away from the States, we couldn’t really get a helicopter cameraman, so I shot the helicopter footage myself and it was quite a challenge to communicate with the pilot. For certain helicopter scenes we used the Continental mount, but for others the camera was handheld. For the scene where the helicopter landed in the village, my operator, shooting a handheld camera, jumped out of the helicopter as it touched down and went running with the people in the field. Michael Cimino wanted to have the hand-held feeling in that shot. There were other scenes that were hand-held like the one where our actors were trying to climb onto the helicopter from the bridge. We needed the space for them to come up the cable, with the camera following them.

I still don’t understand how Bob De Niro, Chris Walken and John Savage did that sequence. They had stuntmen standing by, but they wanted to do it themselves. They were hanging off the helicopter from a height of about 100 feet and flying with it. The only thing they didn’t do was jump from that height into the water, but they did make a jump from about 20 feet up. Even though the stuntmen had checked carefully for rocks in the water, it still looked very dangerous on the screen. It adds to the realism when actors are willing to do their own stunts. It has a great effect on the audience, because they know they are seeing the real thing.

Things really got dangerous at one point when the skids of the helicopter got tangled in the cable that was supporting the bridge. Our stuntman had to climb out and unhook it while the helicopter hovered there and our actors were on the bridge. It was an incredibly dangerous moment and probably the closest call we had during the entire filming.

It was an almost impossible task to shoot the night sequences in the center of Bangkok because the Thai people are very curious and whenever they see a film company shooting they gather around. It was impossible to clear the streets. We had originally wanted to hire 600 to 800 people to work as extras in the street scenes, but it turned out that we had about 6,000 in the background — all for free. We just loved the big crowd and we felt that this was exactly how Saigon must have looked on a Sunday evening, with all the black market activity and the soldiers going into the nightclubs.

It’s a great effect. When you see that first shot of the big crowded street, you think you are watching stock footage, but once the camera starts descending on the crane and coming in to pick up Chris Walken in the crowd, you know that this couldn’t be stock footage. It would have been easy to break that sequence up and do it in cuts, but you would have lost the effect of seeing the real thing. Michael Cimino, being a good director, knows how important it is to capture that realism.

There is a curfew in Bangkok that prohibits people from being on the streets after 1 AM. We knew that we wouldn’t be able to finish our shooting by that time, so we asked the police what would happen if we ran over. They said that everyone would have to go home, but, of course, we knew that they couldn’t make 6,000 people go home who were interested in our filmmaking. As it turned out, they couldn’t, so they just surrounded the whole area with police officers and everybody had to stay there until the curfew ended at 6 AM.

I really enjoyed lighting some of the gambling den interiors in Bangkok. My favorite lighting situation is when you can see just one single bulb — pool hall lighting. I’m crazy about that effect, and that’s why we decided that in those gambling places we would put just a single bulb in the center of the room over the table. The main characters were right under the light, in the center of the composition, and then the light shaded off into the darkness surrounding them. I used this lighting at least twice in the picture for shooting gambling situations. It looks like the scenes were filmed with one light bulb in the middle of the room, but that’s never the case, because one light bulb can never make it look real. You have to help that light bulb, even if it’s a photoflood. You have to add cross light in order to get a single light effect.

We shot an interior sequence inside a go-go bar that was really very small. Again, we went for effect lighting and we brought in a Fisher dolly with two risers to make a crane shot out of the opening scene. We had a hard time getting the dolly into the place, but we just couldn’t figure out any better way to do the shot. Maybe it could have been done by somebody on a ladder with a Panaglide or Steadicam, but I still think you can get better control by setting up a shot like that with a small crane, just as we did. You know exactly what you’re getting — which was important in Thailand, because we never saw dailies. We just relied on the lab to tell us what we were getting.

I really like working with Michael Cimino. He’s a very dedicated filmmaker and a good director. All he thought about during the shooting was trying to make the best possible film. He won’t compromise and he’s one of those directors who would always try to do his best under the worst conditions. He will fight with the studio to get more money or a couple more shooting days because he has a certain image in his mind of what the film should be and he won’t settle for less. I admire directors who are like that.

I feel that today in the film business there are too many directors who are ready to compromise, who are ready to give in to the economics, and who end up with mediocre films. I like to work with people like Robert Altman and Michael Cimino who really want to do something artistic, creative, powerful.

I never had any problems with Michael at anytime during the shooting of the picture, because he knew the same thing about me — that all I cared about was trying to make the best possible film. I really enjoy looking back at the making of The Deer Hunter. It’s possible that some people can criticize certain scenes, and maybe there are things that could have been better, but I guarantee you that we did the best we could under the circumstances.

The Deer Hunter was selected as one of the ASC 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.

For access to all 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.