From Rags to Reservoir Dogs

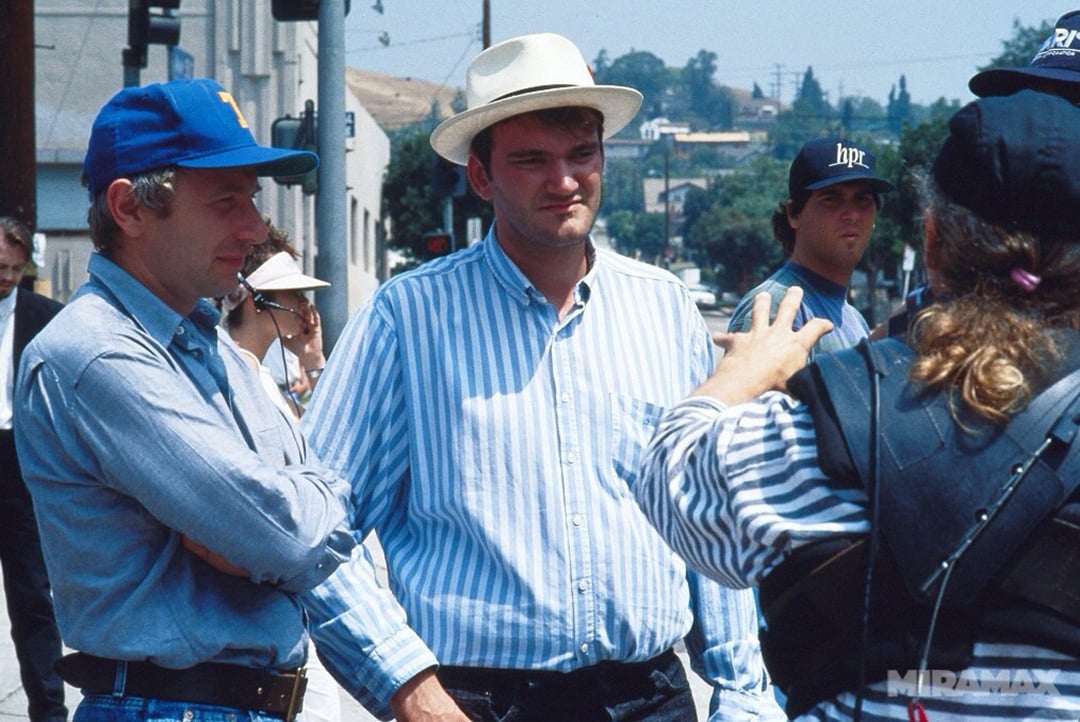

Writer-director Quentin Tarantino and cinematographer Andrzej Sekula detail their approach to shooting what would become a classic crime tale.

Writer-director Quentin Tarantino and cinematographer Andrzej Sekula detail their approach to shooting what would become a classic crime tale.

Cinema history has seen its share of successful collaborations between directors and cinematographers, but none may have been as unlikely as its genesis as that of first-time feature-film partners Quentin Tarantino and Andrzej Sekula.

Currently being touted as the most promising young director in Hollywood (and with an appearance in the September ’92 issue of Esquire to prove it), the 29-year-old Tarantino began his rise to filmic notoriety at the humblest of levels: after adjusting his life’s ambition from acting to filmmaking, he toiled for five years as a minimum-wage clerk at Video Archives in Manhattan Beach. While enjoying the perk of free rentals as only a film buff could, the transplanted Tennessean decided to get some hands-on experience by shooting his own 16mm film. Scamming equipment from friends who were attending area film schools, the budding auteur spent “six or seven thousand dollars over the course of three years,” but describes the results as “not much of anything.”

“I just wasn’t as good as I thought I was going to be, and I more or less decided to look at the project as a learning experience,” Tarantino says now. “That was my film school, and to tell you the truth I think it was the best training I could have gotten. I wound up getting a great education for a relatively modest sum of money.”

Unruffled by his project’s lack of polish, Tarantino began scheming along traditional Tinseltownian lines. “I started writing a script to do, figuring I would raise the money through a limited partnership, like the Coen brothers did with Blood Simple or Sam Raimi and his guys did with The Evil Dead. I worked on the script for three years while trying to get money for it, but it never happened. Scripts get to be like old girlfriends after a while, so I wrote another one and worked for a year and a half trying to get that off the ground. It still didn’t work, and at that point I wrote Reservoir Dogs out of frustration.”

“Saying you don’t like violence in movies is like saying you don’t like tap-dancing sequences in movies.”

— Quentin Tarantino

While crafting the tale that would eventually ignite his career, Tarantino finally managed to sell the first script he had penned (True Romance, which recently went into production at Morgan Creek under the direction of Tony Scott). With some creative coin in his pockets at last, the filmmaker planned to shoot Reservoir Dogs on 16mm over a period of 12 days. Inspired by the pulpy crime novels and film noir movies its author had always loved, Dogs recounts the unraveling of a meticulously orchestrated jewelry heist masterminded by a band of carefully assembled criminal cohorts, whose paranoid-but-practical plans include calling each other by color-coded pseudonyms like “Mr. Pink” and “Mr. White.” The main setting for this violent tale of criminal distrust was originally a run-down auto body shop, but the scope of the picture changed dramatically after Tarantino’s partner and producer, Lawrence Bender, took a copy of the script to his acting class.

There, the script followed a serpentine route, gathering admirers along the way. Eventually the script was put into Harvey Keitel’s hands, and “the actor’s actor” expressed his desire to be involved.

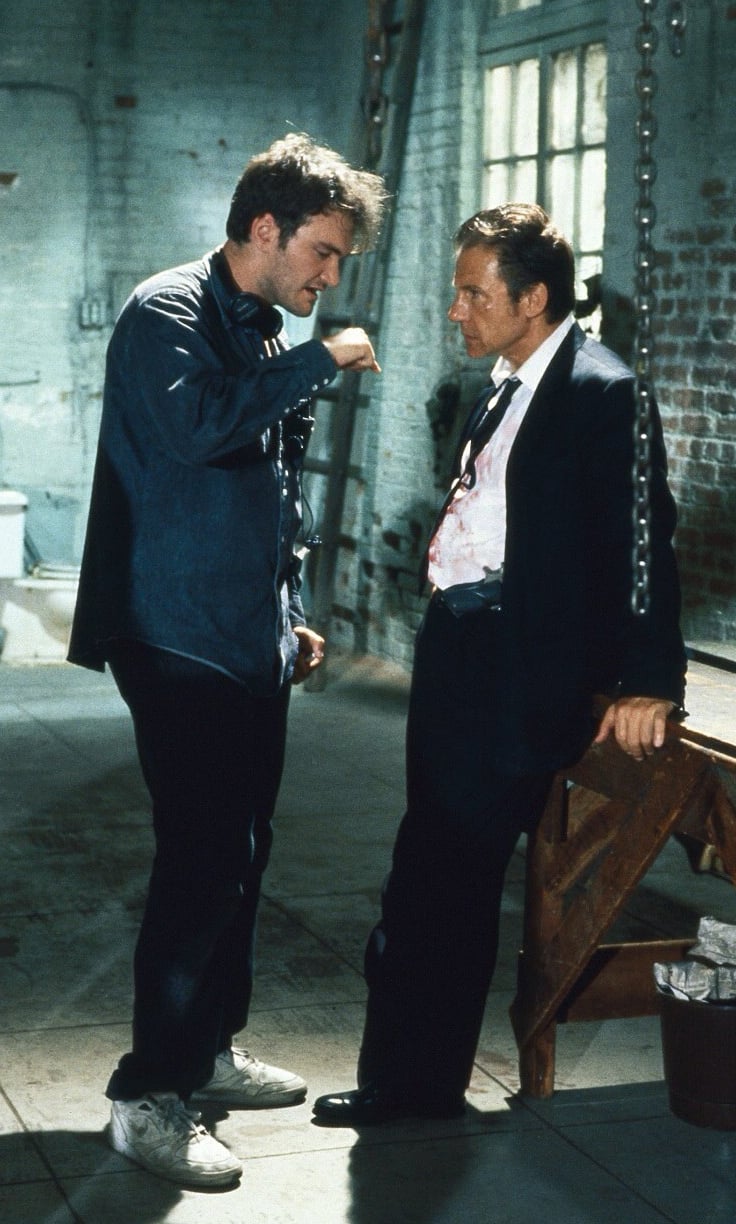

“Harvey’s participation was what gave us real legitimacy,” Tarantino notes. “The script gave us some legitimacy too, but my partner and I were just a couple of kids until he signed on. That moment was really great for me personally, because Harvey’s been my favorite actor since I was 16 years old. To make my directional debut with him [had me wondering], ‘Whose life is this?’”

With Keitel on board, things began to take shape. The film’s budget eventually reached roughly $1.5 million, and Keitel proved to be a powerful magnet in attracting talent for the remaining roles. The director now found himself in the enviable position of choosing from a crop of proven players, but refused to let his excitement overwhelm the material. “It was a very extensive casting situation,” Tarantino reveals. “The only person cast beforehand was Harvey; everybody else came in and read for us. These things sound fun when you’re starting off: ‘Wow, this will be great; we’ll get Christopher Walken for this part and Dennis Hopper for that part and Joe Mantegna for the other one!’ Well, those are wonderful actors, but when you put them all together, maybe the right dynamic hasn’t been created. With an ensemble movie like this, you’ve got to build the group of people perfectly.”

“When we started shooting, I knew very little about lighting and lenses, but I learned a lot from Andrzej.”

— Quentin Tarantino

The completed rogues’ gallery was an impressive array of actors known mainly for intelligent work in independent productions. In addition to Keitel (Mr. White) and Madsen (Mr. Blonde), the main lineup consisted of the fast-talking bug-eyed Steve Buscemi (Mr. Pink), rising British actor Tim Roth (Mr. Orange), Chris Penn (Eddie Cabot), Eddie Bunker (Mr. Blue), infamously unpredictable cult icon Lawrence Tierney (Joe Cabot) and Tarantino himself (Mr. Brown).

The pieces were rapidly falling into place, but one crucial ingredient was yet to be found: a talented director of photography willing to work on a low-budget independent venture. That selection process was also painstaking, but the interview uncovered an unknown artist with origins completely outside Tarantino’s sphere of experience: 37-year-old Polish-born cameraman Andrzej Sekula, who had sharpened his skills shooting military maneuvers while his eventual director was a 12-year-old watching films at the drive-in.

Sekula says that he first became interested in cinematography after seeing films like Moulin Rouge and Fiddler on the Roof, both of which were shot by Oswald Morris, BSC. He admits, however, that his first love was still photography. “A lot of people see cinematography as the ‘next step up,’ but I really wanted to do still photography,” he says in his thick accent. “You have to have a certain amount of courage to take a camera and go make pictures, and I didn’t. When I started working with a group of people who had the same goal, I gradually shed my psychological shyness.”

Sekula got his first work experience as a still photographer/assistant in a Polish film studio. He later became a compulsory conscript in the army, where he served as a film cameraman. “I was shooting all of these big events, like army exercises,” he recalls with a smile. “The exercises were organized for people like [Soviet president Leonid] Brezhnev and [Romanian president Nicolae] Ceausescu. I was always shooting little close-ups of them followed by big explosions that were like something out of Apocalypse Now. It was actually very good documentary training.”

He put his experience to solid use, working for a time as a television documentary cameraman. After a while, though, he decided to move to England, where he enrolled at the National Film School. There, he was thrilled to find himself under the tutelage of none other than his idol, Oswald Morris. “Going to National Film School was one of the best moves of my life,” he maintains. “Suddenly, I found myself in front of the people I admired as a young boy. There are no exams; they just give you equipment and you do work. In a way it’s a microcosm of the film industry, probably an equivalent to the American Film Institute.”

“You can create a skeletal plan for a shoot, but the real art of cinematography is in the improvisation.”

Sekula trained at the school for 3 ½ years (from 1985 to 1988), then started shooting commercials all over Europe. In his heart, he still yearned to see the mythical movie mecca of Hollywood. He got his chance when he was accompanied by a group of eight directors to America on a trip sponsored by Panavision. “It was my first trip to America, and it was kind of overwhelming to finally see the big film industry,” he relates. “It was really just an introduction to the system, but at least I saw how the place looked.”

After his initial visit, Sekula visited Los Angeles twice more and began making some connections. One of those contacts phoned to tell him that a new director named Quentin Tarantino was looking for a cameraman; Sekula prepared a show reel and awaited a response. “While this was happening I had to go back to Poland because my father had died,” he says. “Quentin wanted to meet me, but I had to leave at seven in the morning. We decided to get together at three in the morning, and we had our first meeting on the way to the airport!”

Tarantino reveals that Sekula sewed up the competition by daring to be bold in his choice of film stock. “Andrzej told us he wanted to shoot the entire film on Kodak’s 50 ASA 5245 stock, which is typically used for daylight exteriors. That’s not the kind of thing most cinematographers would say when they’re competing for a job on a production that doesn’t have much money! But when I talked with him about the way I wanted the film to look, I always talked in terms of colors: ‘I want the reds to be really, really red’ and ‘I want the blacks to be black as hell.’ He picked the stock that would make the film look as rich as possible and make those colors pop.”

With his right-hand man in place, Tarantino took some time out to attend the Sundance Institute Director’s Workshop and Lab in early July of 1991. There, he found himself hobnobbing with ‘resource advisors’ of considerable stature: directors Terry Gilliam, Stanley Donen, Ulu Grosbard, and Volker Schlöndoriff; cinematographer Stephen Goldblatt, ASC; and editor Robert Estrin (Badlands), among others.

After returning from Utah, Tarantino led the actors through two weeks of rehearsals, and principal photography began on July 29, 1991. Over the course of the five-week shoot, the company incorporated a variety of colorful and historic Los Angeles locations, including the Park Plaza Hotel and the wildly expressive downtown graffiti walls at Beverly Boulevard and 2ndStreet. “The hotel has been featured many times in films, but I’m the only director who has used only its bathroom,” Tarantino points out with a chuckle.

Tarantino and Sekula soon found themselves enjoying a smooth exchange of ideas which they attributed partially to powwow sessions held in front of a VCR. “I always try to understand what’s in a director’s mind, so we talked very loosely about the project,” Sekula says. “Quentin and I also watched a couple of films, like The Killing and Breathless. When we came together on the set, we really understood each other.”

“I’m a stickler about framing, so basically I controlled the framing and Andrzej controlled the lighting.”

— Quentin Tarantino

Tarantino notes that he was “very involved” with the cinematographic aspects of the shoot, but also that he understands and appreciates the practical boundaries of his authority. “I took an active interest in the cinematography, because I was after a very specific look,” he says. “When we started shooting, I knew very little about lighting and lenses, but I learned a lot from Andrzej. I wanted somebody I could work with, because I knew that whoever I hired was going to know a whole lot more about cinematography than I did. But on the other hand, I knew more about this movie than anybody. I didn’t want someone who was going to cop an attitude with me. I was prepared to fight if that was the case, but I ended up hiring one of the sweetest and most talented guys around.

“I’m a stickler about framing, so basically I controlled the framing and Andrzej controlled the lighting,” Tarantino adds. “I’ll have a few ideas about the lighting, but his ideas are going to be far richer than mine; he knows a lot more about it. Likewise, he’s going to have some ideas about the framing that will always be taken into account. While I was at Sundance, Terry Gilliam said to me, ‘You know, Quentin, it’s funny, you have a very arch framing. I’m really going to be curious to see what happens when you work with a cinematographer and filter your ideas through another person. I think it will soften your ideas a bit and make them just right.’ And that’s what Andrzej did. The rough edges were showing just a bit, and that one baby-step back gave me what I wanted and kept the shots from looking like wild filmmaking for its own sake. We never used those viewfinder things, either; I hate them, and Andrzej despises them.”

“Conversations with the director are just vital,” Sekula maintains. “You can create a skeletal plan for a shoot, but the real art of cinematography is in the improvisation. If you keep the lines of communication open, it usually leads to those sudden inspirations that make a film special.”

A good example of the pair’s give-and-take occurs during the film’s opening sequence, in which the group of hoods engage in a foulmouthed bull session at a greasy spoon restaurant. “Quentin was originally just going to cut back and forth, but I suggested that we should do a circular move to reveal the characters gradually,” Sekula says. As the gangsters goodnaturedly josh back and forth, the camera glides around them in a leisurely fashion; when the conversation begins to get heated up, the filmmakers switch to more confrontational straight cuts. Fill light on the actors was provided by five 575-watt HMI units hanging over the center of the table, while key light was generated by 12K HMIs and 2500-watt HMI Cinepars placed outside the restaurant windows. “It was a harrowing and time-consuming job getting that sequence right, so that the move wouldn’t reveal the lights. We had to be careful to balance the lighting on the actors, because I didn’t want to move and have the texture suddenly become very flat,” Sekula says.

Since most of the film takes place in one location — a large abandoned warehouse — the filmmakers sought to use a widescreen format that would offer maximum coverage. The shoot’s economic considerations led to the use of the Super 35 format rather than anamorphic, a decision which had both its advantages and disadvantages. “Super 35 allows you to use spherical prime lenses, and it supposedly gives a greater depth of field,” Sekula points out. “True anamorphic give a flatter perspective. Before we started shooting the film, I met with John Bailey [ASC], who has quite considerable experience with the anamorphic and Super 35 formats. He spent a lot of time talking about the pluses and minuses of Super 35. One consideration was getting a three-dimensional effect via lighting and by using the film stock. If the viewer doesn’t see grain or other aspects of the film stock, the effect becomes more three-dimensional; they’re not as removed from the images, so the effect is more realistic. One of the reasons we went with Super 35 was that we could use Primo lenses, which have no distortion. In the warehouse bathroom scene, I used a 14.5mm lens, but there still wasn’t much distortion. The Primos are bloody fantastic lenses.

“With Super 35, the anamorphic squeeze is done in postproduction,” he continues. “We went from the original print to an interpositive and internegative [at Foto-Kem] for release, and then we did the anamorphic squeeze at Deluxe. The whole film was one big optical, and one aspect of that was heartbreaking: the loss of quality [in the squeezing process] was apparent. That’s just the nature of the process. The original print was so clear that you could see the structure of the actor’s eyes. You could still see some of that detail after the squeeze, but a bit of the magic was gone. If I could have chosen, I would have gone with anamorphic in the first place, but it was impossible on our budget.”

“I was taught by guys who shot a lot in the Fifties and Sixties, and they always advised me to use slow stops and build up the light.”

— Andrzej Sekula

The cinematographer notes that his choice of the 50 ASA stock wound up working in his favor. “We shot for 12 hours a day, but we never went overschedule on account of the film stock. We were prepared, so even though it sometimes involved extra lighting, it never became a problem. I think at the beginning, a lot of people were afraid of the 50 ASA stock, but for JFK, Robert Richardson [ASC] used 100 ASA stock and it looked fantastic. I just had to be really careful about exposure because it’s not as forgiving as fast stock would have been. The film’s characteristics are different; there’s not a big a span between shadows and highlights with a fast stock. You don’t want to work yourself into a corner by not being able to cope with all the shadows that result from such a large amount of light. But I would never go into a risky thing without knowing what I was doing. Once you’re shooting, it’s no time to be trying to figure things out. We didn’t have the luxury of a lot of pre-rigging time; we’d just go from one location to another with all of the equipment in a big bundle.”

Sekula’s lighting setups were determined primarily by the stops be favored. “I was taught by guys who shot a lot in the Fifties and Sixties, and they always advised me to use slow stops and build up the light,” he says. “They did it mainly because stocks and lenses were slower, but I started to like that approach. In the warehouse, even though we used 50 ASA stock, I was always between 4 and 5.6. Within this range I could get the best possible performance from the lenses and maintain good depth of field. We built up from the black, which gave us total control over the composition. If I had been using 5296 500 ASA, the usual stock for such a situation, my T-stop range would have fallen between 11 and 16.

“Another thing about using such stops that a lot of people might not consider is that it has an influence on how the film will be edited,” Sekula adds. “If I have a wider shot and everything is crisp, we can stay on it longer than if I were using a fast stop. The audience can see faces much more clearly; if the viewer goes for too long without seeing the actors’ faces, he becomes frustrated, and this frustration leads the editor to cut away more quickly to a close-up. If everything is clear and sharp, I have the freedom to linger on a wide shot; the emotions can build up for longer before we cut to the close-up. I discovered this in my experience editing. It’s one of the big differences between film and TV; because of the clarity of the film image, one can stay with a wider shot longer, giving the editor that extra fraction of a second.”

The camera system of choice was a Panavision Gold camera with a Panavision X as a backup. Sekula used the entire range of Primo prime lenses, but went to a 600mm Canon lens for the film’s unusual credit sequence, in which the cocky felons stride toward the camera en masse in super slow-motion, luxuriating in their criminal savoir faire. The title sequence and a later bar sequence were shot normally at 24 frames per second, with the slow-motion effect added via step-printing in postproduction. “Every second frame was printed,” Sekula reveals. “Quentin was against filming at high speeds, because the step-printing would give us much more fluid, poetic movement. We wanted to give these gangsters a sort of unnatural slowness.”

The filmmakers did use high-speed filming — 100 fps with a Pana-Arri setup — for an “imaginary flashback” in a bathroom, where undercover cop Tim Roth supposedly confronts a group of policemen and their hostile canine companion (in actuality, Roth’s character is mentally acting out a cover story he has concocted to impress his fellow hoods and gain their confidence). The bathroom sequence, which involved a 360 shot, was particularly difficult to achieve, since the room itself was very long and covered with mirrors. “At first I said, ‘Well, this is just impossible. We’re not vampires; the mirrors will show our reflections at some point,’” Sekula laughs. “I put the camera on a track and did a couple of test runs to start looking for places where I could put the lights. Later, when I went around, I still saw the lights in the camera. We managed to solve the problem by having gaffers stand near each light and move them up and down. We were shooting with a 14.5mm lens; when the camera was pointing away from each gaffer, he would raise the light up. When we turned around, they would lower the exposed lights as far as they could. It looked like sports fans doing the ‘the wave.’ I couldn’t put anything on the ceiling, because one could see the whole thing as well as the walls.

To facilitate the lighting of the warehouse interior, Sekula laid pipes overhead, toward the center of the room. “I knew I was going to use wide lenses, so I kept the lights as far as possible from the walls. Outside the windows I had 12Ks; on the pipes, I had 4Ks, 6Ks and 2500-watt Cinepars. If we had two windows in the shot I would use cross-lighting. I used directional light throughout the picture. There were instances when I used frost and opal gels to break it up a little, but in general it was a hard-light show. I had to use a lot of lights, because I had to balance the interior lighting to the exterior lighting.”

This balancing act was put to a true test during the film’s gruesome sequence in which Michael Madsen’s Mr. Blonde, tracked by a handheld camera, walks outside the warehouse to his car to retrieve a can of gasoline with which he plans to continue his sadistic torture of a captured cop. “We were going from inside to full daylight, which was T16 or something in that range,” Sekula recalls. “Since we had to follow Michael back inside the warehouse, I balance the light inside so the adjustment would be small. We shot the scene using a Panavision with a 1,000-foot magazine. It was a little on the heavy side, but very stable.”

When asked if he expects some critical heat for soon-to-be-infamous, blackly comical scenes like Madsen carrying on a one-sided conversation with the cop’s freshly severed ear, Tarantino insists that he won’t water down his filmmaking instincts. “Saying you don’t like violence in movies is like saying you don’t like tap-dancing sequences in movies,” he opines. “It’s just one of the many things that movies can do. You may not like it, but to suggest that it shouldn’t be in the film is ridiculous; that’s artistic handcuffs. If you go to a comedy, you remember that you laughed and had a good time, as opposed to Reservoir Dogs, where you feel like you’ve been hit in the head with a gun butt for two hours.”

In the wake of the film’s success at the Cannes Film Festival and a spate of pre-release screenings that had the Hollywood community abuzz, both Tarantino and Sekula offered enthusiastic assessments of their future together. Tarantino revealed that he intends to continue working with Sekula in the future, beginning with his next film, a crime anthology tentatively title Pulp Fiction.

Sekula, for his part, is still a bit dazed at his newfound prospects. He’s shot two feature films since completing Reservoir Dogs (the upcoming Tehachapi and Three of Hearts) and now finds his mailbox stuffed with new scripts. “Reservoir Dogs brought me a lot of attention, and I’m somewhat surprised,” he confesses with undue modesty. “I’ve gone from a guy looking at others with hungry eyes to being in American Cinematographer! Success can be frustrating, though; I get a lot of offers for pictures I’d love to do, except now there are conflicts. But I’m not complaining! Sometimes I just sit down and think, ‘God, I am bloody lucky.’”

This article was originally published in AC, November, 1992. Some photos are additional or alternate.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.