The Astonishing Images of I Am Cuba

Daring photography and lyrical style enhance 1964 agitprop epic, which stands as a record of the island’s dashed dreams.

Films of propaganda, more than any other kind, mirror the moments of their creation. They can be inspiring or irritating, artistic or klutzy, preachy or subtle. A few take on lives of their own, making is possible to appreciate them for values that transcend their agendas. So it is with certain films made solely to glorify the Bolshevik Revolution, such as Battleship Potemkin and October. Even the Hitler-sponsored Triumph of the Will is now admired as a meisterwerk of German craftsmanship.

Now we can add to the list I Am Cuba. Co-produced by Mosfilm, the largest studio in the USSR, and the Cuban Film Institute (ICIAC) with a budget of $600,000, it went into preparation in November 1962, only weeks after the Cuban missile crisis almost triggered World War III and a year after America’s disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion. It was the fifth year of Fidel Castro’s reign, following his hard-won overthrow of the tyrannical government of Fulgencio Batista, and the dream of Utopia to come had not yet been obliterated by the grim realities of life under the new regime. In the film, Castro is the savior of his people, Communism is the hope of the world, and bloated American capitalists are helping Batista to rape the island.

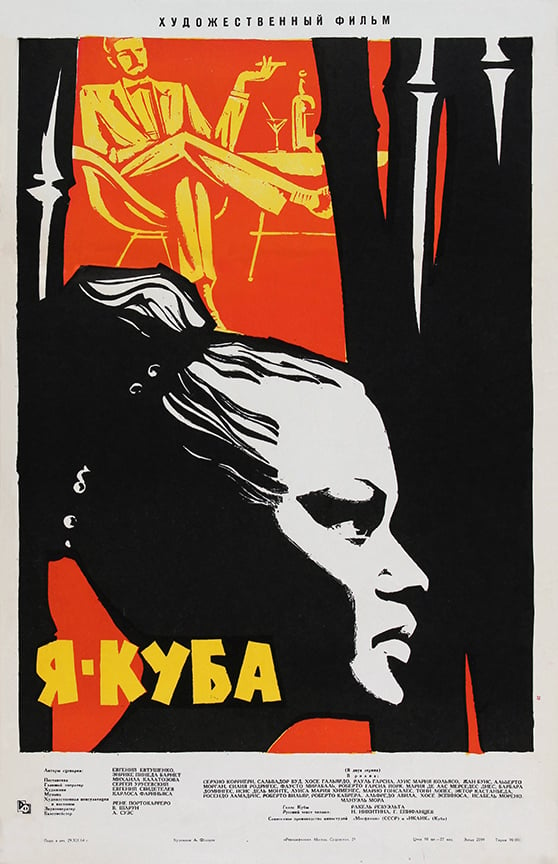

By 1964, when the picture (Soy Cuba in Cuba and Ja Kuba in the USSR) was completed, the country’s dreams had eroded further. The horrors of Batista and the Mafia seemed no worse than the realities of Castro and the USSR. Any movie which sets out to combine the frigid austerity of Eastern Communism and the hot-blooded sensuality of the tropical West is bound to be something strange, and I Am Cuba was not palatable to either Castro or Khrushchev.

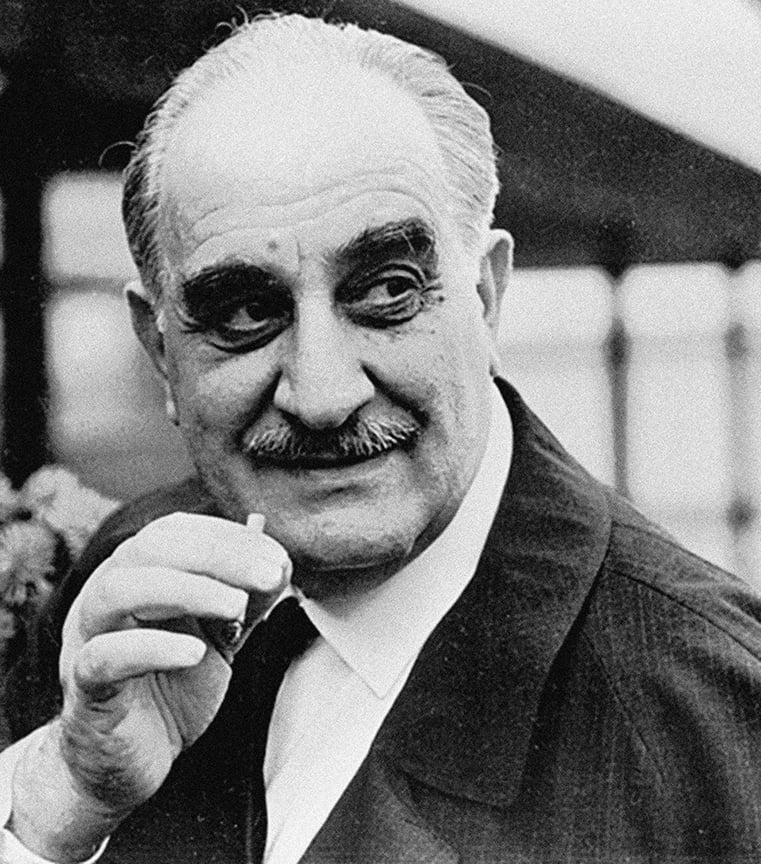

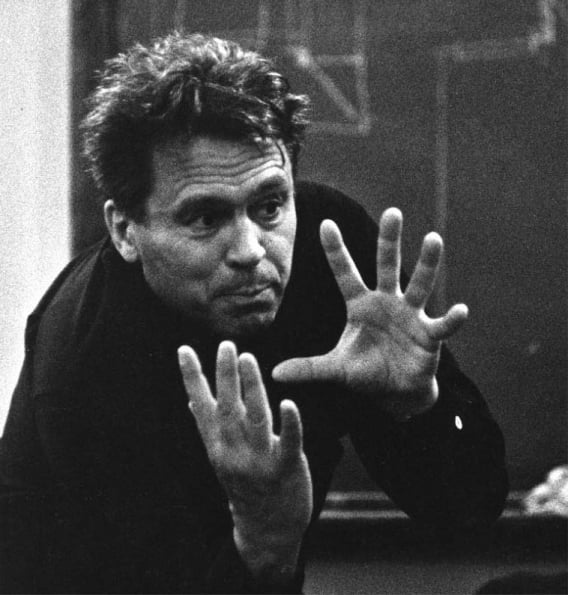

What makes this flop of its day something for the ages is not its demolished “message” but its inventive black-and-white cinematography. Its visuals are as startling today as were those of Citizen Kane 55 years ago. Soviet director Mikhail Kalatozov, famed for his lyrical The Cranes Are Flying, and director of photography Sergei Urusevsky were determined to create a work of modern art composed of seemingly impossible camera moves.

The result is 140 minutes of determinedly different images, including exceedingly long takes through which the camera roams constantly. While the picture is too long to fully sustain such a cascade of virtuosity and there are times when it becomes too artsy for its good, it is undeniably a feast for the eyes. Taking ourselves as the heavies and Castro as the Lone Ranger requires more than a grain of salt, but the visuals are worth it.

The screenplay, by Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Cuban novelist Enrique Pineda Barnet, portrays the last gasps of Batista’s reign in 1959. It consists of four segments, which are linked by poetry read in Spanish by the “Voice of Cuba,” Raquel Revuelta, and echoed by Russian translators. In the new prints, dialogue is translated (loosely) in English subtitles.

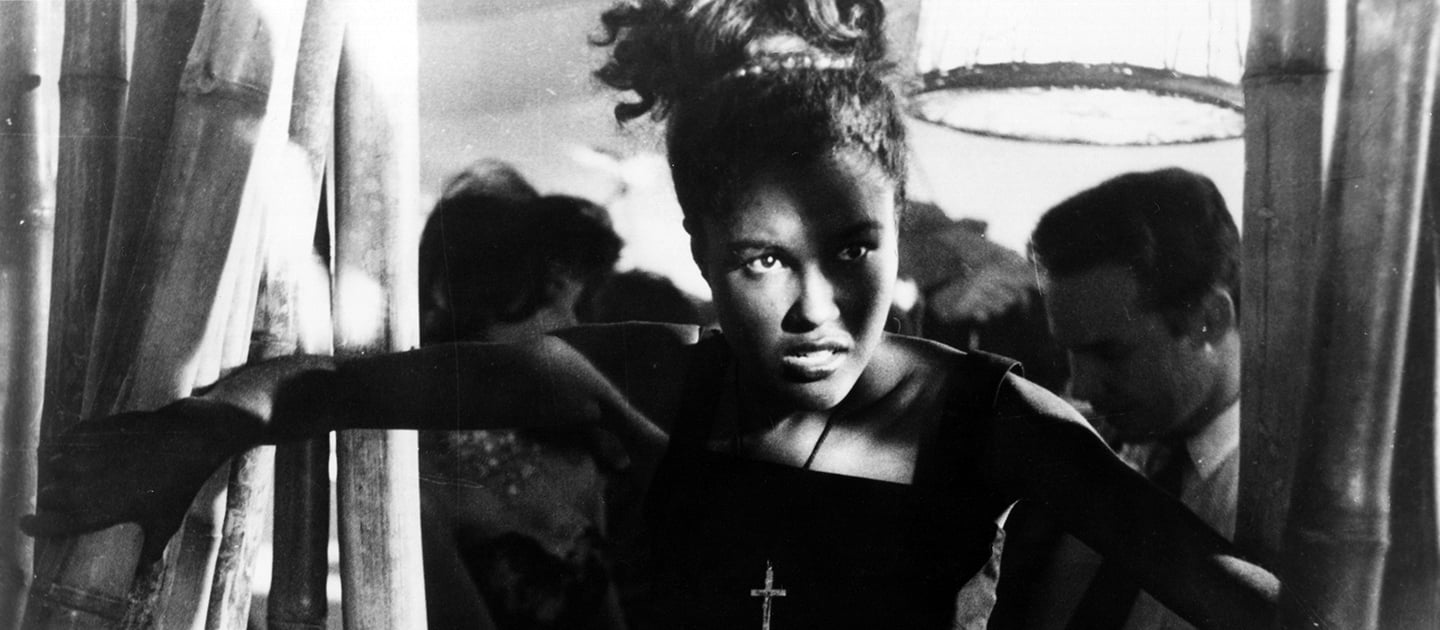

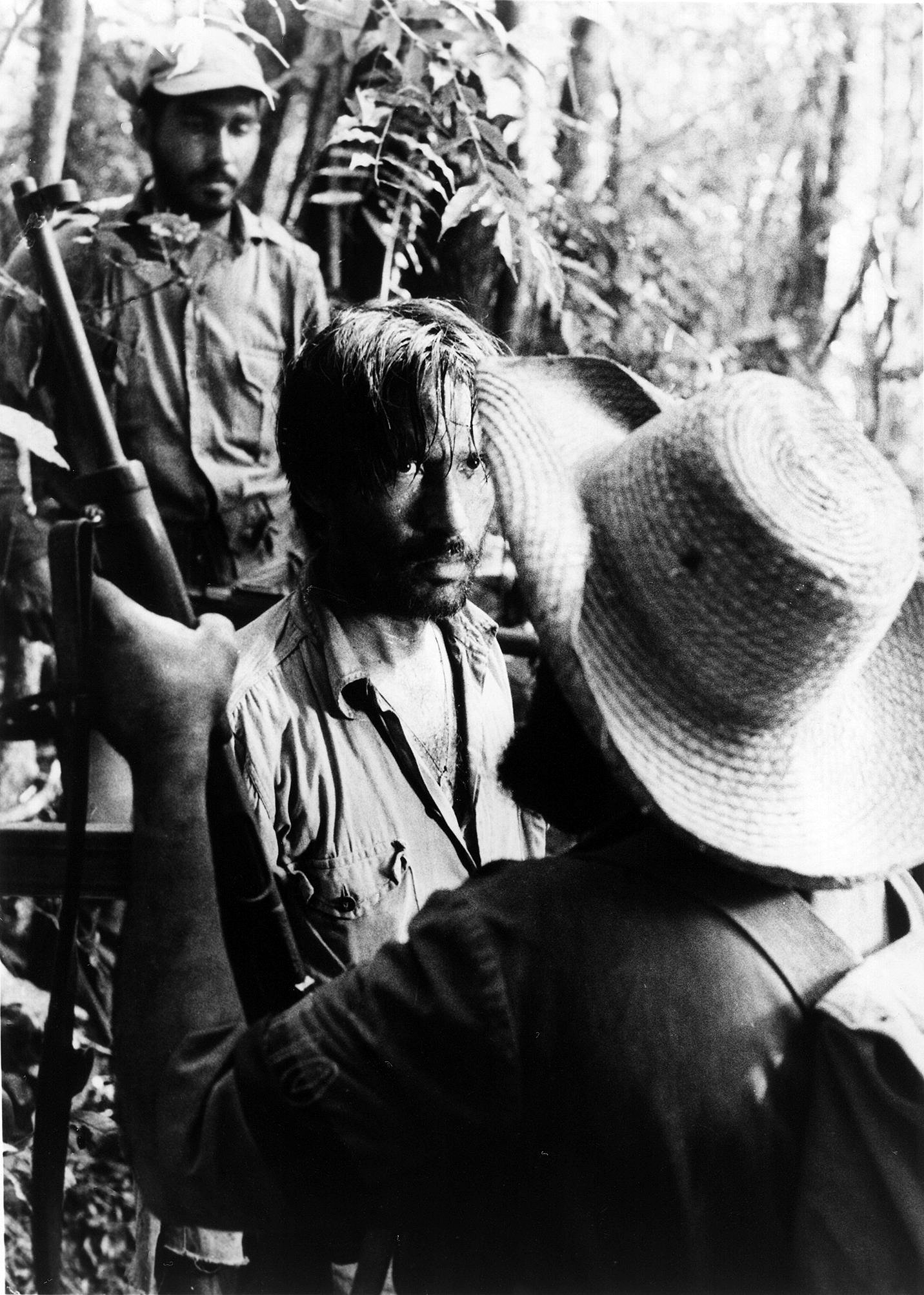

The first story tells of the lovely Maria, forced by circumstance to be a prostitute in a Havana nightclub catering to boorish Americans. A customer with a strange fetish steals her crucifix and causes her double life to be revealed to her fiancé. The second tale is of a peasant whose cane farm is sold by the landowner to United Fruit Co. just at harvest time. He gives his teenage son and daughter his last peso and sends them to the village. While they happily drink Cokes and play tunes on a jukebox, he slashes crazily at the cane until he is exhausted, sets fire to field and his shack, then collapses and dies. A long third segment concerns a student revolutionary who reneges on his determination to assassinate a corrupt police officer and eventually is murdered by the man whose life he spared. The last episode concerns freedom fighters in the Sierra Maestra as they vengefully surge to victory after Batista’s bombers have destroyed their homes.

Heralding the striking black-and-white images to come is a surreal title sequence photographed from a helicopter which approaches Cuba over a sullen ocean and passes over the island. The masses of palm fronds appear silvery white, like glowing feathers reaching into a dark sky, and bodies of water resemble pools of molten lead. Beauty and foreboding are conveyed in about equal measure. Next, a long take moves down a narrow waterway through an impoverished village.

There follows the most impressive camera move of the film. On the roof of a high-rise building, a rock ’n’ roll trio blares as the camera strolls with contestants in a bikini beauty contest through a boisterous crowd of mostly hefty tourists. The camera moves to the edge of the roof and glides down the side of the building to a swimming pool level swarming with cocktail drinkers, sunbathers, gorgeous women and even a tourist photographing the scene with his Bolex. The camera swerves to glance down from a terrace overlooking the beach, then turns its attention to a tall, bikini-clad brunette as she rises from a chaise lounge and walks into the swimming pool. The camera follows, plunging beneath the surface to show a mosaic of the swimming bodies of young women, fat capitalists and the stringy pimps. The sound also goes underwater, yielding a muffled, distorted version of the revelries above.

It should be emphasized that this entire sequence is accomplished in one continuous, unhurried take! The desired ambience of Dante’s Inferno is achieved, although fat capitalists might suspect that it looks more inviting than the prospect of tiling your own soil, as proffered by Castro.

All of the scenes that follow are just as deliriously unconventional. There are more German tilts than could be found in a Karl Freund film festival, wide-angle distortions that would have startled Orson Welles, and low-slanted camera angles that give Herculean stature to heroic revolutionaries in the tradition of the Russian classics directed by Sergei Eisenstein and photographed by Edouard Tissé. There are many unusually long handheld scenes through which the camera meanders intricately as an angry and sometimes agitated observer. The camera repeatedly challenges danger, convention and even the laws of gravity.

Urusevsky (1908-1974), a graduate of the Institute of Fine Arts in Moscow, was a fine painter and photographer who was a combat cameraman during World War II and later became one of the great pictorial stylists in Soviet films. In 1965 he wrote of his Cuban experiences in the Iskusstva kino magazine:

“We saw the film as a kind of poem, as a poetic narrative. I’m not saying that this is how it actually turned out!... What did seem absolutely necessary to us was the creation of an image — to the point of hyperbole… We tried to get to the point where the viewer would not be just a passive observer of events happening on the screen but would experience them with the actor… I as a cameraman always wanted to do more than simply fixate what was happening in front of the camera. I am interested in getting the basic theme of the scene: love, loathing, misery, joy, despair.

“Rhythm is the key. Obviously, when the cameraman is running alongside the heroes, first close to them, then approaching them again — peering into the face of one, then another, stumbling into trees, falling down — the panorama cannot be and ought not to be even. This technical ‘failing’ is in fact an artistic virtue… Whatever episode we film, whatever camera we use, the vital condition is an inner agitation, a creative emotion during the filming — I even dare say inspiration.

“Using a handheld camera gives you opportunity of making free, complicated panoramic pans which are impossible without a stationary camera with the usual cart on its tracks. This is not to say that I am agitating for every film to be shot with a manual camera. But when we tried shooting I Am Cuba with a stationary camera and tripod, it just didn’t work — it was as if our hands dropped down by our sides… If I move forward a bit, holding the camera in my hands, or back a bit, or shake the camera from side to side, the image becomes more expressive and more alive.

“It seems to us that you do not have to show the viewer literally everything… There is always something that ought to be left unspoken. You have to give the viewer the chance to be more active, to figure out something for himself, to connect the dots… We decided to solve the social issue by way of association. Take the beginning of the film: before the subtitles you already have the long pan along the shore, over the palm trees. We wanted to show the long island, which we are approaching more and more slowly… After the titles there is a pan over a poverty-stricken village. Black sky, white palms. The whole pan was shot from a boat. In the foreground you have a black boatman. The whole pan is shot around him – you see first his back, then his legs. (By the way, this pan was shot using a 9.8mm lens. The possibility of this lens still amazes me.) I am convinced that the impression of poverty is not created so much by the poor village itself that we are passing by as by this boatman, whose bare back and legs we constantly see… At the end, the camera comes to a black woman with naked children crossing the river… In the next sequence, taking the camera into the pool is justified because water is the visual link between the two scenes.” [Evidently the Russian meaning of “pan” differs from ours; throughout this long scene the camera rides behind the boatman.]

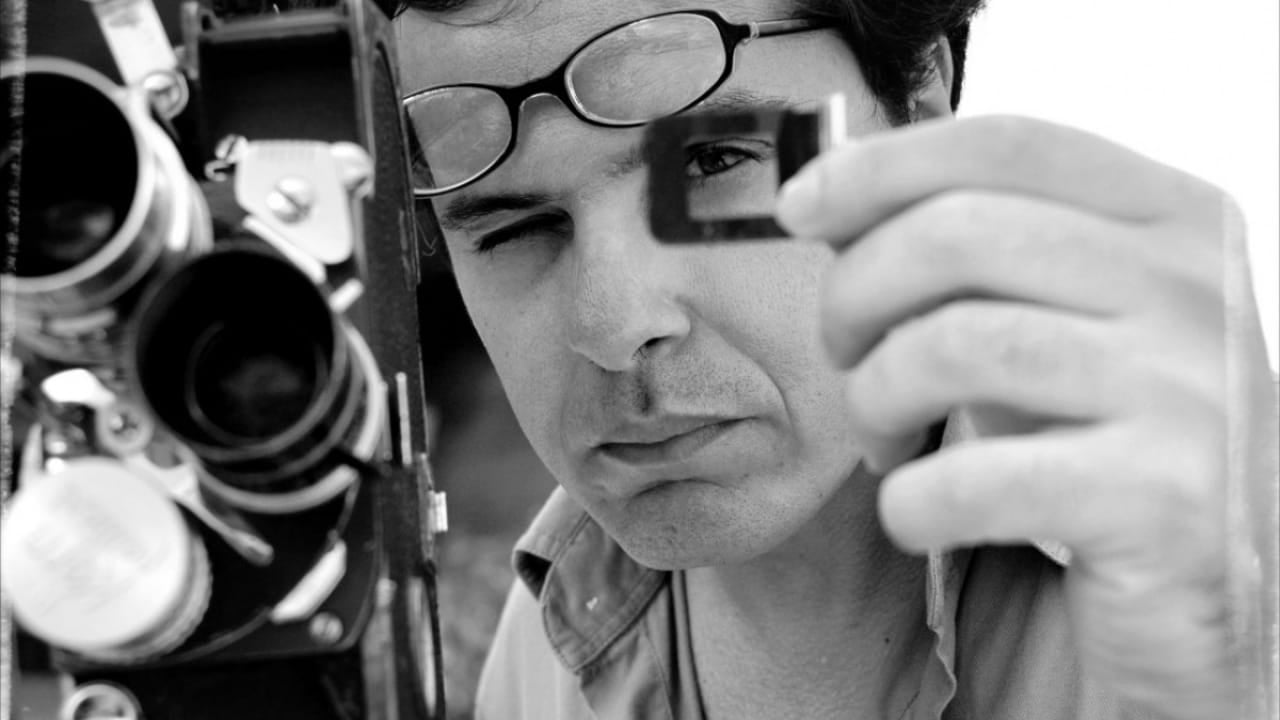

Alexander Calzatti, the first camera operator throughout production, is the son of a famous cinematographer, was the student of the legendary Tissé, and served as an intern on Kalamanov’s The Cranes Are Flying in 1957. For the past 12 years, Calzatti has lived in Los Angeles, where he photographs music videos and second units. His son is also a cinematographer and his daughter is a fashion photographer. His father, now 90, also lives in Los Angeles.

“I was 22 years old [when we filmed I Am Cuba],” Calzatti recalled recently during a visit to the ASC Clubhouse. “We delivered equipment to Cuba, and Cuba gave us hotels, transportation, food and many things. We gave Cuba 20 small Vassilev cameras that were a strange combination of Éclair and Arriflex, and a camera named Friendship that was much like a BNC with reflex. This camera was never used in Cuba because of the motor works on 50 cycles and Cuba uses 60 cycles. They tried to make a device to compensate, but it never worked.”

A small camera with a 400' capacity was used throughout because of the preponderance of handheld work. Two cranes were brought from Russia for certain scenes. Everything was filmed MOS and the dialogue was post-synched. An excellent score for orchestra and voices by Cuban composer Carlow Farinas was recorded in Russia.

“Soy Cuba was probably the first big-budget picture made with just one camera, an Éclair CM3 Camiflex, and mostly one lens,” Calzatti laughed. “We changed lenses very rarely, from super-wide to just wide. We used a 9.8mm Kinoptic for 90 percent of the film, and the other lens was just an 18mm, which we used like a normal or maybe a short telephoto. We had a lot of problems with the small French motor because anytime we tilted the horizon the camera changed speed! A specially trained Cuban technician followed his instincts and fixed it. There were no special effects except what was done in front of the camera. Everything was hand-made, garage-style. Mr. Urusevsky always liked to make everything himself, but he was getting old and the tropical climate was hard on him, so he decided to use a team operation. We tried to use the camera like basketball players, with somebody beginning the scene and passing the camera to another.”

Calzatti told of spending long nights with Urusevsky discussing ways of achieving his ideas. “He was a painter, an absolutely artistic person, but his technical knowledge was zero,” Calzatti explained. “So he’d just ask me to give him something, like combinations of filters, camera supports, or doing some kinetical movement for the camera. We built with him some 83 systems. If you look carefully there are maybe 100 splices in the film because of many long scenes — the camera edited many things. The camera changed points of view from subjective point of view to objective many times. Point of view was a major target of what we wanted to do.”

The bikini contest scene is the most striking example of this technique. “We filmed it on a very tall building with two roof levels. We built a primitive wooden elevator which was just lowered by hand. My assistant was an ingenious mechanic, Konstantin Shipov, and we had a Cuban named Caliche who was a genius. Somebody stayed in the elevator, the first operator gave him the camera, he went down and the third guy took the camera through the lower level and the pool. The camera could go into the water because we had it in a plastic bag from the supermarket.”

Infrared film, which records only the part of the spectrum beyond the visual red, was needed to lend a dreamlike quality to several important scenes. Foliage reflects infrared and is recorded as white while other colors are rendered in values dissimilar to those of panchromatic film. It was used effectively, most often for day-for-night effects, in some American films beginning in the late 1930s. Memorable examples include the serial Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars, the big-scale Westerns Fort Apache and Pursued, and several crime dramas made by Universal in the 1950s.

Urusevsky used infrared to create the eerie effect of white palms trees, dark skies and leaden water in the title sequence and white stalks of cane in the second story. When the betrayed farmer slashes at the cane with his machete, the long leaves resemble swords attacking from all sides.

“We wanted the cane white because sugar is white — it was sugar,” according to Calzatti. “Urusevsky had used infrared before. Russia didn’t produce infrared film, so I came to a manufacturer in Kazan who made film strictly for the military – for shooting the other side of the moon, for spying on American objects. They hand-made infrared for us in what looked like a kitchen. It was of very high contrast and very low sensitivity — around 30 ASA — and it was on celluloid instead of tri-acetate. We had no infrared meter, and no infrared marks on the lens, so many times the results were unpredictable. After a while we just used our instincts, and we became friends with infrared. What you see in the film is okay, but we shot much footage to select from. Each scene was done for 15 or 20 times, so it never was filmed spontaneously.

“For our normal negative we used Orwo Superpan, which was East German Agfa film, ASA 64. We used lots of filters, mostly homemade black and white nets.”

After the farmer sets fire to his house, a complicated crane move carries the camera up for a high angle of the scene. To permit the director to view these scenes during shooting, the crew devised a closed camera video system utilizing Urusevsky’s personal television set, which he brought from Russia. This is probably the first use of what has only in recent years become common procedure. The death of Enrique, the student revolutionary in the third story, is depicted in an eerie fashion. The camera swirls up and the image of the murdered youth seems to dissolve. A filter was used to distort the image, oil was poured over a plastic sheet in front of the lens, and a gradual fade into a negative image was done in the laboratory.

The funeral cortege of the student is shown in a single take wherein the camera rises from the street, moves up the side of a high building. Crosses the street, enters a window, moves through a room where workers are making cigars, then goes out the window and continues moving while observing the mourners in the street. Calzatti explained how it was done:

“We used a special cable device which I built in Moscow before going to Cuba. We planned to fly the camera between two big buildings in a major street. Because of security and insurance problems we used it in a little street. We used two cables and a small cart with eight wheels and a fork underneath where the camera was placed at the [end] of a handheld move. The secret of how we attached the camera to the cart was a magnet, part of which was in the cart and part of which was built on the camera. From the window the camera moved out about 100 feet.

“We worked sometimes 12 to 16 hours a day and stayed about two years on the island,” Calzatti said. “Everybody was so enthusiastic [that] we were infected by it, and we worked very hard. Very soon after we came back to Russia, more than half of our crew died. I survived because I was very young.

“I think there is great value in this film because it could never be done again. It was very valuable to the Cubans because never was Cuba done so beautifully on the screen. It was like the Mexican films of Gabriel Figueroa – Kalatozov and Urusevsky looked at many films [shot by] Figueroa because he invented this image. This picture did for Cuba what Figueroa did for Mexico.

“It was really a cameraman’s film because everything was orchestrated for the camera. I think of my life in two parts: before this film and after, although I was never the cinematographer of this film, I was just a cameraman. Any medium — literature, poetry, architecture, painting, film — reflects the reality of life, but never the whole reality of life. The artists can choose what part of life they want reflected, so it has become a very dangerous tool for any sort of propaganda. This is what I Am Cuba is; it’s strictly a political film.

I Am Cuba was shown briefly in Cuba and the USSR in 1964 and incurred the wrath of both Castro and Khrushchev. It wasn’t released in any other countries and vanished as quickly as the expectations it offered so fervently. But after three decades an almost happy ended has come to pass. The film surfaced, without subtitles, at the 1992 Telluride (Colorado) Film Festival tribute to Kalatozov. The director lived to see its triumphant resurrection only months before his death. The following year it was shown at the San Francisco International Film Festival, where a sold-out audience gave it two standing ovations during the screening. Now, under the auspices of Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese, Milestone Film & Video have added subtitles and put it into general release.

Here is proof — if any is needed — of the immense power of motion pictures, and especially of cinematography; proof that an inspired work can transcend ideologies and stand on its own as a work of art.

In 2019, the film was included in the ASC’s roster of 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century. Learn more about this list here.

That same year, Milestone Films remastered I Am Cuba in 4K, jointly presented by Martin Scorsese and Francis Coppola. The company worked from a fine-grain 35mm film interpositive that was the source for their original 1995 home video release. The scanning and restoration was done at Metropolis Post.

You'll learn much more about this work and the film via Milestone’s press notes, found here.

The insightful 2004 making-of documentary I Am Cuba: The Siberian Mammoth, directed by Vicente Ferraz, offers a candid portrait of the ambitious production and can be watched here.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.