The Maltese Falcon and the Picture Partners

The writer-director’s essay on the importance of the “Picture Partners” — the director-cinematographer working relationship.

In the November 1941 issue of AC, Arthur Edeson, ASC’s expert camerawork in the crime drama The Maltese Falcon was one of the recent releases discussed in the column “Photography of the Month.”

While uncredited, the review was penned by AC editor-in-chief William Stull, ASC. Of note is how the release of Citizen Kane in May of that same year had already become extremely influential, with Gregg Toland, ASC’s memorable camerawork still clearly in the forefront of people’s minds.

The Maltese Falcon

Warner Bros.-First National Production.

Director of Photography: Arthur Edeson, ASC

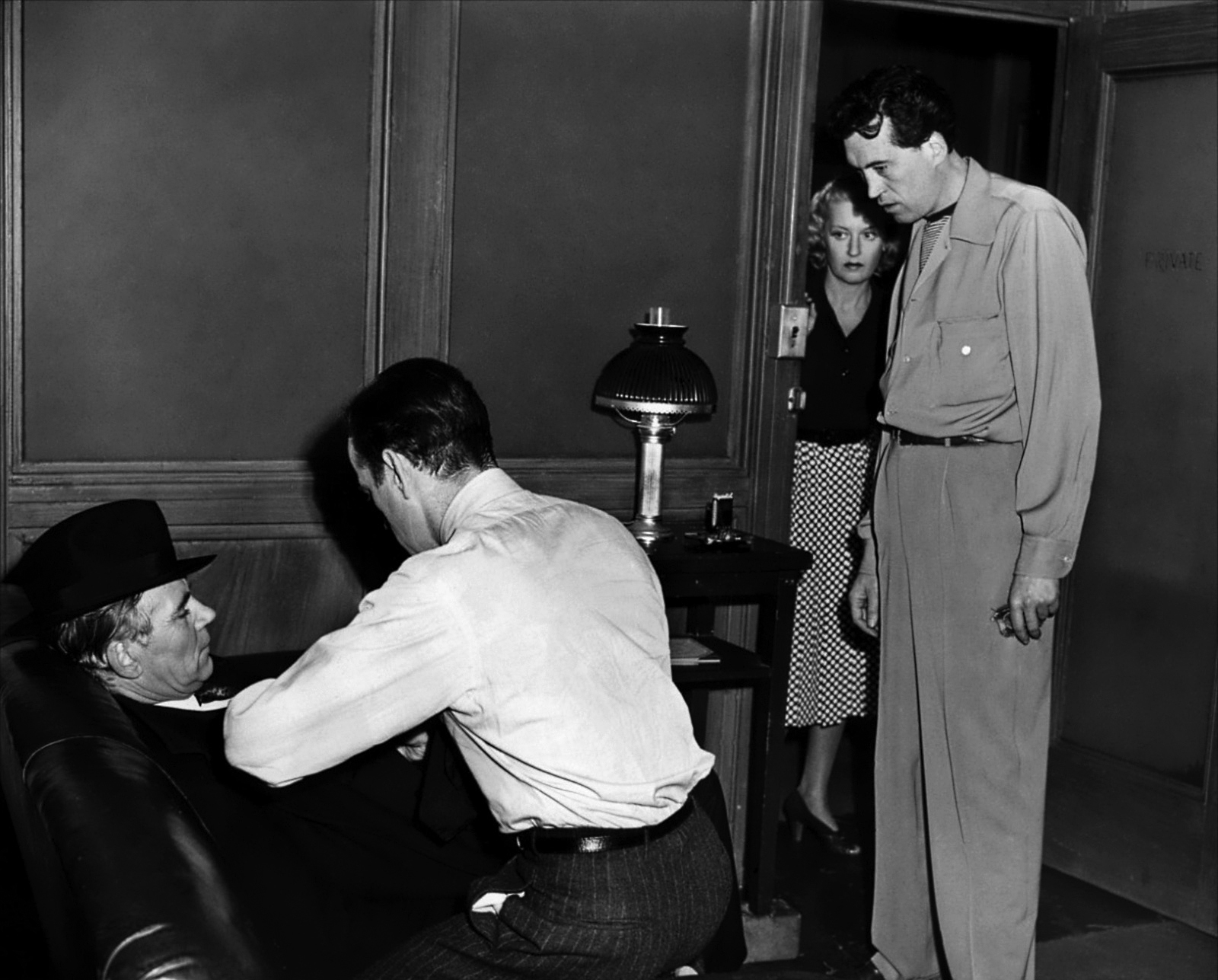

The Maltese Falcon is an unusually interesting picture. If you can detach yourself from its fast-moving melodrama (no mean feat, but the way) you’ll discover that its cinetechnical interest is at least as great as the dramatic. It is one of the first films to point the way to a successful adaptation of the Citizen Kane photographic technique to more routine production. Much of the Kane technique has been retained: There is strikingly similar depth and crispness, the use of wide-angle lenses and roofed-in sets, not done just occasionally, when somebody thought of it, but throughout the picture, as an integral part of the production. Both director of photography Edeson and director John Huston have done very well with it, too.

The note of realism dominates. There is far less of the conventionally melodramatic effect lighting of the usual “whodunit,” and a surprising lot of the realism of a documentary. The use of the increased-depth technique adds noticeably to this impression, even though at times the distorting effect of wide-angle lenses is somewhat apparent. However, Edeson has handled this phase of the picture with remarkable skill, for this distortion is not nearly so noticeable as it has been in many another picture.

To this writer’s mind, somewhat excessive use was made of the trick of shooting up from comparatively low camera angles on roofed-in sets. It is always a good trick when the action calls for it; but while it was at times used legitimately in this picture, it was rather more frequently used strictly for effect, and when there is no bonafide reason for such an angle, the dramatic continuity of a film is a good deal the better if such tricks are avoided.

Edeson’s handling of the sets themselves was excellent. Some of the sets were distinctly drab affairs, representing unspectacular offices, apartments and the like, such as may be found plentifully in San Francisco. Both the sets themselves and Edeson’s treatment of them added markedly to the realism of the picture, and Edeson is to be congratulated on the way he has used them, avoiding the usual photographic clichés, and stressing the note of drab reality. His handling of the ship-fire sequence is very effective. So, too, is the way he has handled the backings: So often the weak point in a picture, he has contrived to make them look like real backgrounds, rather than obvious backings.

An interesting sidelight on the production is the fact that the wide-angle lens used is not the conventional 24mm objective so generally used, but a special 21mm lens which is part of the cinematographer’s personal equipment.

The following essay penned by Maltese Falcon writer-director John Huston was published in AC Dec. 1941. It gives a clear take on how grateful he was for Edeson’s expertise on the picture, and how their working relationship on his debut feature became an eye-opening experience, carrying over to his next assignment, In This Our Life (1942), photographed by Ernest Haller, ASC.

Picture Partners

By John Huston

Noted Screen Writer, Director of The Maltese Falcon

Not so long ago, my concept of cameramen was that they were nice fellows who concentrated their efforts on turning out pretty compositions and making the leading lady look glamorous. To be perfectly frank, I also had an idea that the present system of crediting them as “Director of Photography” was more or less a polite fiction — dressing things up with a new name, and not much else.

But that was before a change from writing scripts to directing them put me out on the set actually to work with these men of the camera. Practical experience very quickly forced me to revise my ideas, and convinced me that the industry’s cinematographers are, as a class, perhaps the most invaluable and yet generally underrated men in Hollywood.

My first big surprise came when I discovered that these men are interested in a lot more than just turning out pretty pictures. They do that as a matter of course; it’s part of their job. But much more than that, they’re storytellers par excellence. Instead of using written or spoken words, they tell their stories with the camera. Often — if you’ll only take advantage of their knack of visualizing drama — they can, with a simple, pictorial effect, put over dramatic points upon which writers or directors may have toiled and worried vainly.

“As a writer, I often wondered why so many changes were made in my scripts between the time they left my typewriter and the time they reached the screen. Now I know!”

— John Huston

Speaking for the moment strictly as a writer, I wish there were some way in which the men and women who write our screenplays could have an opportunity of working more closely with the men who photograph them. As writers, most of us naturally think largely, if not exclusively, in terms of dramatic situations and dialog. Yet we’re writing for what is fundamentally a pictorial medium. The situations and dialog are necessary, heaven knows, but if we lose sight of the basic pictorial appeal of our medium, we’re likely to use a lot of words to put over a point or situation which could much more easily be gotten across by visual means.

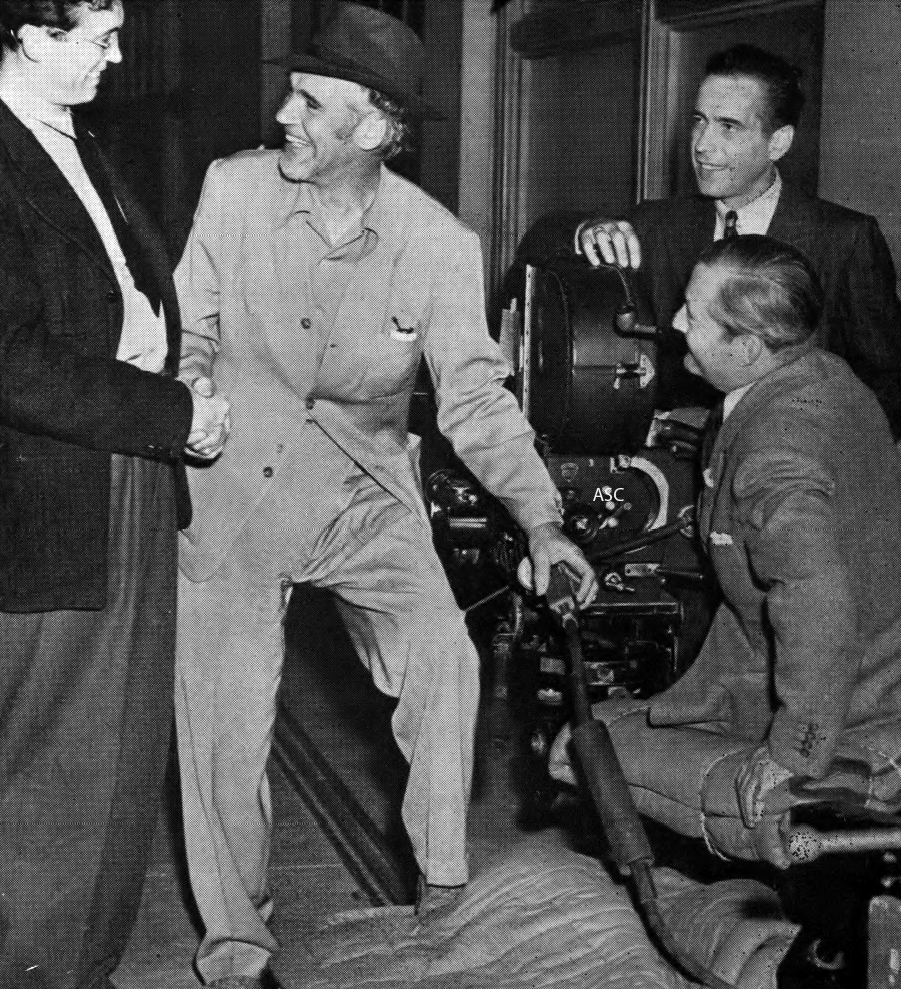

As a writer, I often wondered why so many changes were made in my scripts between the time they left my typewriter and the time they reached the screen. Now I know! Like most of the rest of us, I simply didn’t know how to write for the camera: I sometimes wrote things which, when they reached the set, turned out to be impractical cinematically; at other times, and for the same reason, I’d try to put into words, things which could more easily be told in pictured action. Even in the course of directing two pictures I’ve repeatedly seen a story-minded cameraman like Arthur Edeson, ASC with whom I made my first picture, The Maltese Falcon, or Ernest Haller, ASC with whom I am now making In This Our Life, make suggestions which would bypass a page or so of dialog at a time, putting over the same idea visually in less footage — and far more effectively.

As a director, I’ve come to value these suggestions from the cameraman very highly. Of course, I’m still pretty young and new at the business of directing pictures, but I can’t conceive of any director who really has the interest of his production at heart ever getting so big and experienced that he could ignore the suggestions that come so naturally from his partner at the camera.

And the man at the camera can be just that — a partner to the director: really a co-director taking full responsibility for the visual side of the production, leaving the director free to concentrate on the actors and their work. That title, “Director of Photography” is a lot more than a mere phrase! It’s a very specific definition of the invaluable service the cinematographer can offer to a production — if we’ll let him.

What do I mean by the “visual” side of the production? A lot more, I’ve found, than merely pictorial composition, high or low-key lighting, and the star’s appearance! For example, our scripts today concern themselves largely with dialog, with only a sketchy indication of where a scene is laid, and little, if any indication of camera angles and business. If you shot a picture solely from the indications given in the script, you’d probably end up with a picture that was 85% or 90% long shots.

“I’ve already learned that if you only give him a chance to make the suggestion soon enough, a skilled cinematographer can show you how to suggest things with the camera, rather than having to build them in expensively literal sets.”

The writers, you see, expect the folks on the set to break a scene up into its component individual angles or (as I think the Russians call them) “cutting pieces.” And one of the first things I learned when I started directing was that this isn’t nearly as easy as it might sound. You’ve got to figure out how each shot is to be coordinated with all the other shots that will ultimately make up the sequence, even though the individual, intercut shots may be photographed days apart.

Then there are details to remember — such as, in a series of intercut individual shots of two people talking to each other, keeping the figures on the screen approximately the same size; keeping directions of movement straight, so actors don’t get apparently crossed up between one scene and the next; even keeping track of the direction in which a player ought to look at another one offstage so as to keep things flowing naturally on the screen.

My experience has been that a director can do a much better job with cast and story if he’ll let his director of photography serve as a virtual co-director, taking almost complete charge of these details. And most directors of photography — at least such men as Edeson and Haller — are glad to do so. They admit it makes them work a good deal harder, but they welcome that because it gives them a chance to contribute more constructively to the production — to do their part to make it visually, as well as verbally and dramatically, outstanding.

Here’s the way we’ve worked it in practice so far. Before we start shooting, the cinematographer and I study the script together, in as much detail as possible. We agree on the basic mood and visual treatment generally. Then as shooting progresses, we work together in perfect partnership. At night, the director of photography takes his script home and analyzes the next day’s shooting in terms of visual treatment, just as I study things to prepare myself to handle them dramatically. A chap like Haller, for example, will usually break things down into quick sketches to indicate graphically each scene, angle and set-up.

In the morning, before shooting, we’ll check these sketches over together, making sure that our concepts are reasonably well in agreement. Then we’ll proceed to carry them out on the screen, each dealing with his own part of the job. Of course we sometimes don’t quite agree; then, with fellows like Edeson or Haller, we’ll talk it over until between us we find just why the scene should or shouldn’t be done that way. For example, sometimes I’ll listen to the way Ernie wants to deal with a certain scene, and then in my ignorance I’ll ask why it can’t be done some other way. To that, he may reply with a good, logical reason based on his many years of experience making all kinds of pictures — or we may find we’ve accidentally hit on something a bit new and useful. In any event, the picture is a lot better for that sort of cooperation.

Frankly, I think the general run of our picture — “A” productions, anyway — would be immensely benefited if they could have the advantage of the cinematographer’s picture-trained brain participating in the final stages of scripting, as well as on the set. Whether you agree with Orson Welles’ concept or not, most of us are agreed that Citizen Kane was in every way a remarkable achievement in cine-storytelling: and I don’t think it is in any way detracting from Welles’ acknowledged brilliance as a producer-director to point out that he made full use of the capabilities of Gregg Toland, ASC by having his director of photography work closely with him during the last 8 or 10 weeks of preparing the production, and then gave him a very free hand in guiding the visual side of the picture during the shooting. Without that, it is very safe to say that Citizen Kane would not have been so arrestingly cinematic.

That sort of pre-production cooperation would pay dollars-and-cents dividends, too. I’m sure it would cut down measurably on “protection shots,” set construction and the like. I’ve already learned that if you only give him a chance to make the suggestion soon enough, a skilled cinematographer can show you how to suggest things with the camera, rather than having to build them in expensively literal sets. For example, one of the biggest-appearing scenes in Kane was, if you’ll analyze it, suggested by simply using a huge fireplace, a massive staircase — and an imaginative camera.

“The ideal system, I’d say, would be to have the director, the director of photography and the scenarist work closely together as the script is put into final shape for shooting, sketching out each angle and set-up as they went along.”

Often, too, in writing on preparing a script, we’ll note down this scene or that sequence as “process,” and mark it for the attention of special-effects staff. Actually, it might be more efficient to film that action by straightforward methods — and other scenes we’ve completely overlooked could be done much more economically as process shots! The cinematographer’s unique grasp of both technique and production methods, if called into consultation earlier, could undoubtedly save us a good many more or less costly mistakes along these lines.

The ideal system, I’d say, would be to have the director, the director of photography and the scenarist work closely together as the script is put into final shape for shooting, sketching out each angle and set-up as they went along, until they finally reached the shooting stage with a script combining words and sketches to make a genuine blueprint of the completed production. In that way, I am sure, we could save on set construction, save on shooting time, save on normally overshot footage and “protection shots,” and turn out a production that was dramatically and visually more coherent, doing it much more easily and surely because of taking the real picture mind of the cinematographer into full partnership.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.