Creating The Night of the Hunter

Cinematographer Stanley Cortez, ASC recounts making one of the most visually striking motion pictures of all time.

“So, you are the new cinematographer to solve our complex photographic problems? Well, I am very happy to meet you, you big bastard.”These were Charles Laughton’s first words to Stanley Cortez, ASC, when they met for the first time at the Hotel George V in Paris.

Cortez responded: “I am very happy to meet you, you fat S.O.B.”

With this dialogue, accompanied by warm, friendly handshakes and feelings of mutual respect, began a relationship of many years which culminated in the making of Laughton’s only film directorial effort, the classic The Night of the Hunter. Laughton’s untimely death left an unfilled void in the worlds of theater, film and literature. He was, as Cortez observes, “a brilliant, sensitive artist; a source of inspiration.”

“It was a joy, creatingThe Night of the Hunter.”

— Stanley Cortez, ASC

The occasion was a cocktail party in honor of Cortez, who had just arrived from the States to take over the photography of The Man on the Eiffel Tower. Production had foundered due to photographic problems. According to Cortez, “It was a strange project, put together by Franchot Tone and Irving Allen and shot on Ansco Color, a reversal process. Tone directed part of it, but when he was in a scene Charles would take over, and when both Charles and Franchot were in a scene Burgess Meredith would direct. When all three were in the scene nobody was left but yours truly, so I directed.

“Dissolving to when the picture finished, everybody left Paris to catch a ship, leaving Charles and me behind to do the finishing sequences. That’s when I got to thinking that Charles would make a good director. I saw Paris through his eyes, all of Paris, and he knew Paris better than most Frenchmen.”

About six years later, producer Paul Gregory put together a package for United Artists to film Davis Grubb’s novel, The Night of the Hunter, with Laughton as director. The team had worked together on a producer-director basis on several successful plays. Laughton invited Cortez to his home in the Hollywood Hills. Gregory was there, as was James Agee, who was writing the screenplay.

“The meeting took place at the pool,” Cortez recalls. After the story was discussed, Cortez said, “Charles, as this is your first picture, I’m going to bring some equipment up here and I want you to study it and get yourself accustomed to the different lenses, what they’ll do, and not do. Not that you should be totally absorbed, but just to know what is going on when we get you with the crew.” He brought the equipment to the house on the following Sunday.

“I became the student and Charles became the professor,” Cortez says. “Not from a technical viewpoint, but from a philosophical point of view, his thoughts and feelings from an actor’s point of view and a writer’s — because he was also a very fine writer. He had a great cultural sense, a sense of good taste.

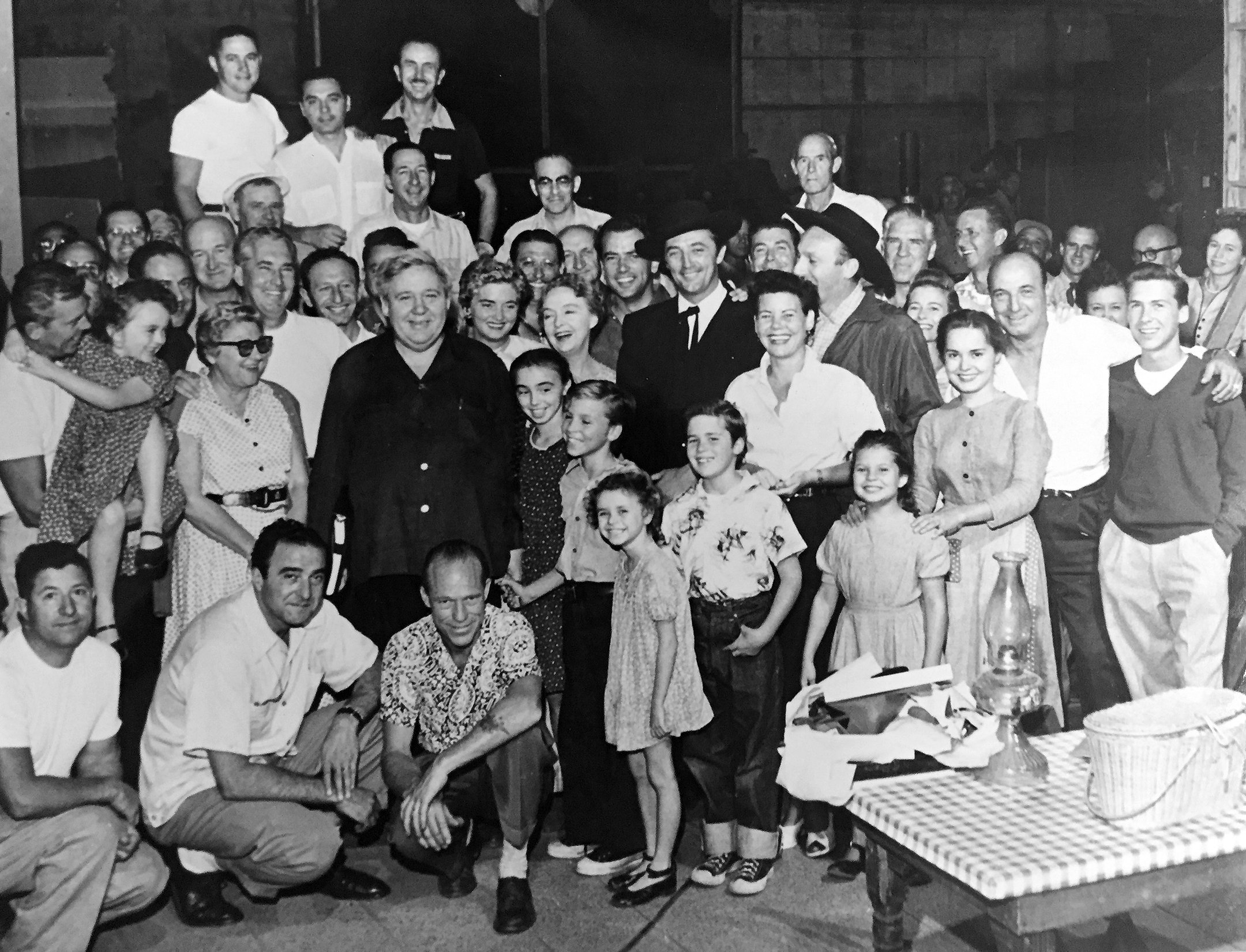

“The picture was to have been made for a certain amount of money and in a certain period of time. He assembled a wonderful cast and we made the picture in 36 days. That same picture today would have taken — I don’t know how long, but let’s say more than double.

“When a cinematographer says a certain picture is close to this heart, it’s because of the fun he had doing it and in this case the tremendous sympatico — not a phony veneer, but truly a sympatico — that existed between Charles Laughton and myself. Notwithstanding the others who contribute so much to a production, on the firing line, when all the chips are down, there are two people involved: the director and the cinematographer. It was a field day for me in terms of extreme creativity that Charles appreciated.

“For this picture, a group got together every night over a couple of drinks at a restaurant down on La Cienega, the Frascatti Inn. It consisted of Charles, Hilly Brown [the art director], Milt Carter [the assistant director], Bob Golden [the film editor], and sometimes Ruby Rosenberg [the production manager]. The purpose of this was to sit down with Charles to help him make a great picture. Which is what it became, but it was ‘way ahead of its time.’

“In this picture I was very careful in selecting a crew, I wanted to have people in there who would have the chemistry to support Laughton — not to excite him, but to give him a boost and not create a bad situation because of Charles’ lack of technical knowledge. I was there to protect Charles, and if I wasn’t there my boys knew how far they could go. It proved that my choice of people was excellent and they — Bud Mautino, Sy Hoffberg and Bob Hauser — supported Charles 100%. The chemistry was there, and if there’s no chemistry, brother, you’re in a bad way.

“Enough credit has not been given to people like Hilly Brown, Milton Carter or Robert Golden. Hilly is a great architect and he designs his sets from a high point of view, always looking down on something. Milton Carter kept things going, and made it easy to talk with Charles. Charles’ sensitivity as a director — who, in my view must be the boss, and if he’s a halfway decent person he’ll get our response — permeated the entire staff. Seldom have I ever seen a group of men who were so eager to come to do a day’s work, tough as it was. There was never any squabble about lunch or dinner, it was a matter of, ‘Damn it, we’re going to get this out and do the best we know how.’”

The story of The Night of the Hunter occurs in 1930 in the Ohio River Valley country of West Virginia. Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum), a self-ordained preacher, travels the country searching for widows to marry, then kill and rob. Arrested for car theft, he is thrown into the same cell with Ben Harper (Peter Graves), who is to be executed for the murder of a bank teller. Harper had robbed the bank of $10,000, which was never recovered. Powell is unsuccessful in trying to learn its whereabouts. When Powell is released, he goes to visit Harper’s widow Willa (Shelley Winters) and children, 9-year-old John (Billy Chapin) and 5-year-old Pearl (Sally Jane Bruce). Only the children know that the money is stuffed in a doll Pearl always carries, and they were sworn to secrecy by their father.

Powell wecomes popular in the small town and Willa, prodded by well-meaning townfolk, accepts his proposal of marriage. Once he is convinced that Willa knows nothing about the money, Powell murders her, disposes of the body in the river, and tells the townfolk she has run away with another man. He tries to harass the children into leading him to the money, but they escape in a row boat. They flee down river while he follows on a stolen farm horse.

The children eventually are taken in by Miss Rachel (Lillian Gish), an old lady who looks after river orphans at her farm. When Powell finds where the children are, he tries to terrorize Rachel into giving them up. After a long siege, Rachel wounds Powell with a shotgun blast. He is arrested, put on trial, and condemned to hang. John and Pearl remain with Rachel.

Such are the bare bones of the story. It is in the fleshing out that the greater interest lies. The novel is written in a pretentiously poetic style, while the movie is built out of clean-cut, simplified compositions reminiscent of the black-and-white line illustrations popular in books and periodicals of the Thirties. Despite its grim theme and relentless atmosphere of menace, the picture contains a surprising amount of humorous incident, some of it decidedly grotesque and occasionally slapstick. Aside from the quaint patois of the rural folk and the medicine-show con art of the evil preacher, comic bits are artfully placed at moments of suspense to ease the tension of the viewer and give him an opportunity to chuckle at the right places instead of giving vent to nervous laughter at moments when it would be fatal to the mood.

One such episode occurs when Powell almost captures the children in a dark fruit cellar and a shelf full of home canned goods crashes down on his head. Later, when he is within an inch of catching the youngsters, he takes an Oliver Hardy fall into a mud hole. And when the preacher, brandishing his deadly switchblade, tries to crawl under a porch after the boy, Rachel aims her shotgun at his stern and forces him to back out.

Mitchum’s performance — arguably his finest contribution to the screen — seems inspired. It takes courage for a popular romantic star to accept such a role, a situation not unlike Robert Montgomery’s precedent-setting portrayal as a murderer of women in Night Must Fall (1936) — a superb but predictably unpopular performance. Preacher Powell is introduced as the driver of a stolen touring car. He addresses an invisible presence: “What’s it to be, Lord, another widow? Has it been six? Twelve? I disremember. You say the word and I’m on my way. You always send me money to go forth and preach your Word. A widow with a little wad of bills hidden away in the sugarbowl … Sometimes I wonder if you understand. Not that you mind the killin’s. Yore book is full of killin’s. But there are things you do hate, Lord: perfume-smellin’ things, lacy things, things with curly hair.”

His most popular sermon demonstrates the power of love over hate, which he symbolizes with a wrestling match between his right hand, the fingers of which, are tattooed with the letters L-O-V-E, and the left, on which H-A-T-E is spelled out. “These fingers has veins that lead straight to the soul of man!” he tells the awed rustics. He is by turns charming, comical, grotesque and terrifying.

Equally fine is Lillian Gish as Miss Rachel, a character invested with the spiritual qualities Powell pretends to possess. Small and deceptively frail-looking, she proves more than a match for Powell — convincingly. One of the strangest scenes in the movie occurs when Powell, lurking in the night shadows outside Rachel’s house, begins to sing a hymn used as a leitmotif at several points in the film, Leaning on the Everlasting Arms. Rachel, sitting in the dark with her shotgun cradled in her lap, joins in the singing, supplying the harmony.

Billy Chapin and Sally Jane Bruce are excellent, the stalwart boy and the innocent girl mirroring perfectly the words spoken by Lillian Gish at the end of the picture: “Yes for every child, rich or poor, there’s a time of running through a dark place; and there’s no word for a child’s fear, and no ear to hear it if there was a word, and no one to understand it if they heard. God save little children! They abide and they endure.”

Shelley Winters is impressive as the tragic widow. James Gleason is a fine river character and Evelyn Varden is true-to-life as the loudmouthed matchmaker who bullies Winters into marrying the murderous preacher and is last seen leading a lynch mob at his trial.

Interesting use of animal symbolism occurs throughout. The children’s flight is punctuated by shots of vulnerable animals — a frog, rabbits, a turtle, sheep. The preacher, frustrated by the escape of the children, emits a wolfish growl which swells into a distorted howling. When Rachel blasts him with her shotgun, he yelps and whimpers like a wounded wolf. Rachel and her flock of children scurry single-file down the street like a mother quail and her young.

“Charles was a great student of D.W. Griffith,” Cortez recalls. “Before the picture started we ran many of Griffith’s pictures, not with the idea of copying Griffith but because Charles wanted to learn from him. He wanted to do certain things Griffith did. That Griffith-like iris-in shot, where we closed down on the boy in the basement window, was a matter of sheer necessity, however. We wanted to dolly in to the boy, but we couldn’t get the camera that close no matter how much we tried, and even if we could get in there it would take too long. We had no zoom lenses available, so I used an iris that we used on the lights. It was about five feet square and we had to oil it up because it hadn’t been used lately and was rusty as hell.

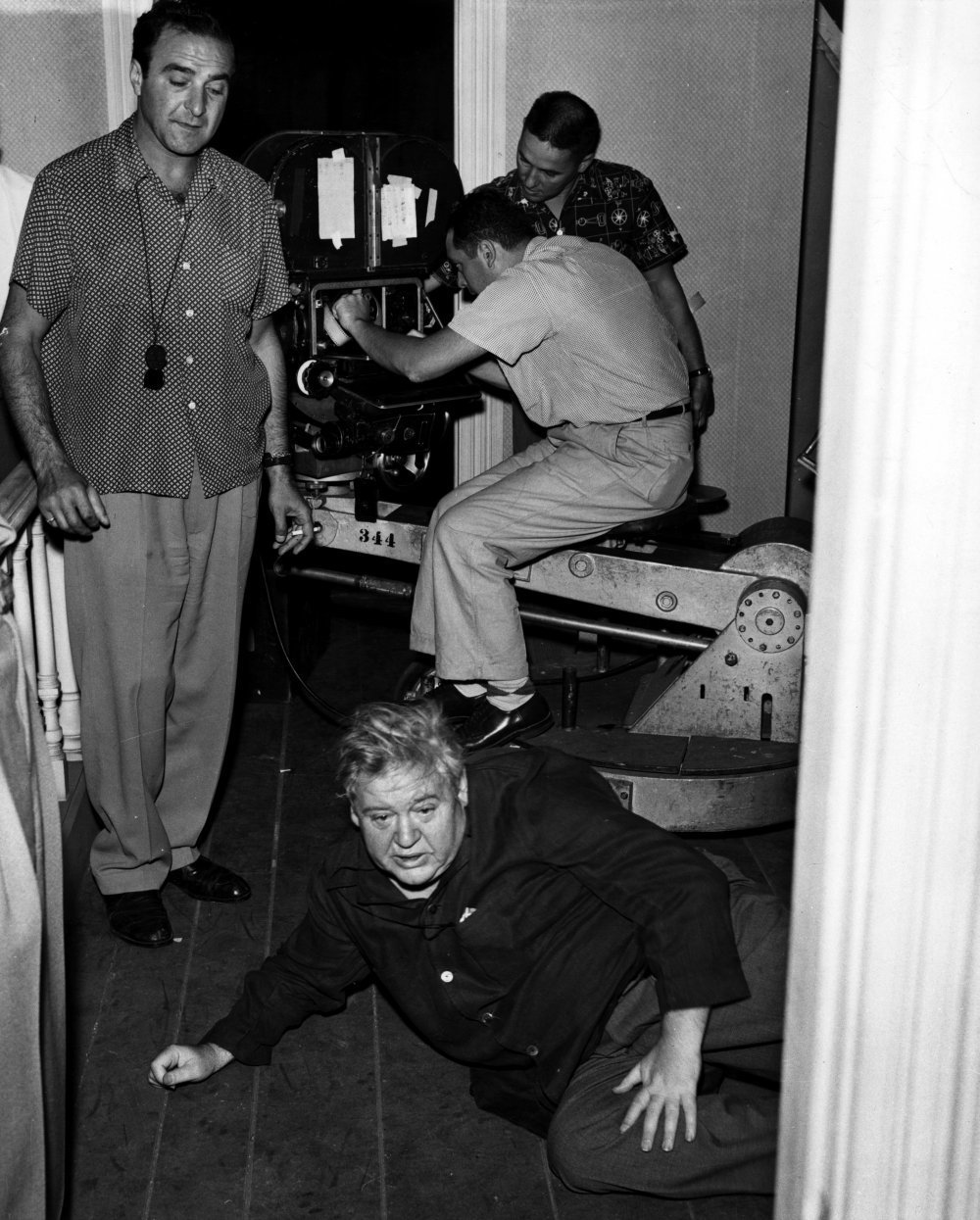

“Photographically, that picture had many problems and there were certain scenes that didn’t quite come off. Like the sequence around the back stairway, when the kids are crawling as Mitchum is chasing them — there was something that wasn’t quite right. Problems because of the schedule — we had to make it in a certain amount of time — and, of course, it was Charles’ first picture. No picture is 100%; you’ll find flaws in any picture, whatever it is — even Gone With the Wind, even in a David Lean picture.

“Now we had certain sequences down the river with the children and Hilyard Brown did a hell of a job for us in the building of the river and the houses of Stage 15 at Pathe. The only way to get some points over was to stylize it. The skies were all lit artificially and though it was in black-and-white it had a strange phosphorescent quality in it.

“Before the picture started, I made tests with Tri-X film to see what the film would do not only from a speed standpoint but from a dramatic point of view, which to me is more important. The technique is one thing and the dramatic concept is something else. In my book, the dramatic aspect is far more important, because through the dramatic concept the communication is made to the audience and this is the crux of the whole thing. I used Tri-X on certain sequences, but not throughout the entire picture, not for the speed value but for the dramatic value. By that I mean the blacks. They had the luminous, phosphorescent light I wanted in certain sequences. Tri-X was used in the house where the children lived, with the little stairway going up the left side, and in two other sequences. But generally, we used our normal film and a normal lens; nothing was pushed, nothing forced.”

Tri-X also was used in one of the more complex scenes in which the children watch from a hayloft as Powell rides along a moonlit horizon on his stolen horses. “We built the hayloft almost to the top of the stage and had a half-moon doubled in,” Cortez explains. “The stage was very small, and our idea was to give it some depth. That was a midget on a pony riding along, not Mitchum on a plow horse. It was shot from the top of the stage looking down. We used Tri-X because I wanted those blacks to go black, and it had nothing to do with the speed of the film, it was the color rendition, the tonal values. The impression was gotten over dramatically, a dramatic concept to communicate to the audience — sort of being colorful in black-and-white.”

Although most of the picture was made on sound stages, some real exteriors were used. “Exteriors were made at the Rowland V. Lee Ranch, in the San Fernando Valley,” Cortez says. “We built a street out there and at the head of the street we had a small, phony lake. For that sequence Jack Rabin, through very fine matte work, doubled in a real river steamer going across and it made that little lake look as though it were part of the Ohio River.”

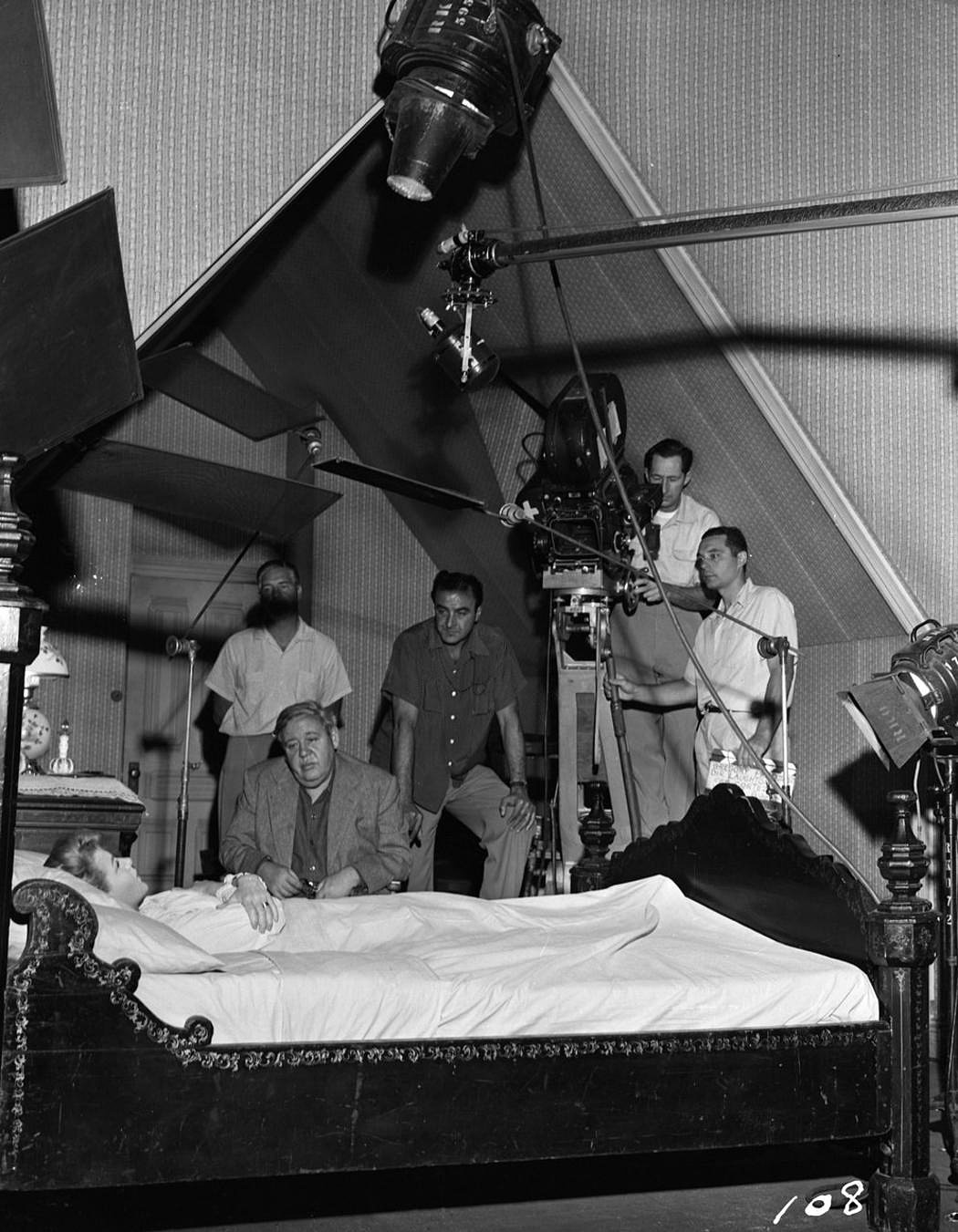

Undoubtedly the most striking sequences in the picture are the ones in which Mitchum murders Shelley Winters and another wherein fisherman James Gleason discovers her body sitting in a Model T Ford on the bottom of the river. Both scenes have an eerie “feel” that transcends what is contributed by the weird lighting, the design of the set and the acting of the players. According to Cortez, there is a strange reason for this.

“I am a devoted student of music, so much so that I use music a great deal to give me a clue to a given problem. While Charles was rehearsing Bob, I was making certain preparations when Charles sat down and started to watch me. He said, ‘Stanley, what in the hell are you doing?’ I said, ‘None of your damned business, Laughton’ — in a nice way, of course. But he insisted. I said, ‘Charles, I happen to be thinking of a piece of music right now.’ And he said in a typical Laughton way, ‘And, pray, may I ask what the music is?’ I said, ‘It’s called Valse Triste.’ There was a long pause, then he said, ‘Damn it! How right you are! It has to be a waltz!

“Then, he did something that never happened in my career before — it may even be unique in the industry. He sent for the composer, Walter Schumann, to come on the set and see what I was doing visually so that he, Schumann, could interpret it aurally! And that’s how the waltz tempo of that scene got started.

“People say, don’t you plan these shots? I say, to a degree I do, from the standpoint of lighting, but I must be elastic, I must be open, because when you read a script that’s one impression, but when you look at a stage, and you hear actors speak in the actual set, it becomes a completely different thing.”

“You may wonder why I thought of that particular piece of music. Composed by Sibelius, it was a part of a saga and told of a scene that takes place in a graveyard at one minute past midnight. Bones come to life and do a dance in sheer mockery of life, which was the exact thing Mitchum was doing because of the love and hate thing. That was what I had in my mind but I couldn’t tell him because I was afraid he might think it was a phony thing on my part — which can happen — and I thought, ‘Don’t tell anybody.’ I’ve used that idea on many occasions, thinking about certain pieces of music as a writer might think about something that could give him a clue to the opening line and get him started. With me, it’s music. Charles appreciated the musical idea and tried to get the ballet thing into it, but that has nothing to do with what I’m telling you, which is only how I tried and in many ways succeeded in using music as a key to a lighting format. It has played an important part in my career.”

The Valse Triste motif was carried over into the underwater sequence, which was filmed in a special tank at Republic Studio (now CBS Studio Center). “We had to create a spiritual effect,” Cortez says. “I had eight powerful titans — the strongest sun arcs available — on a huge crane suspended over the tank.” The swaying of the water weeds and the flaxen hair of the dead woman create an almost hypnotic effect in these eerie scenes.

“The visual concept of the whole picture changes in the very last sequence, which is completely different from any other sequence in the picture,” Cortez points out. “It was warm, like a Christmas party. It was Charles’ thinking that he wanted to make it like that. He said, ‘Stanley, I want to get the feeling here that this is a Christmas party wrapped up in a beautiful package and off they go.’ I said, ‘I know what you mean, Charles,’ and this was our approach. The relationship between Charles and myself was extraordinary in the sense of unity of concept, of a fusion of thinking. And so, the sequence at the end was so different, like night and day.”

Cortez believes it is impossible to explain in so many words how the creative aspects of a film are achieved as opposed to the technical aspects. “I just did it. Either you do or you don’t. You see something and you react, the juice is turned on and — boom! — you go. People say, don’t you plan these shots? I say, to a degree I do, from the standpoint of lighting, but I must be elastic, I must be open, because when you read a script that’s one impression, but when you look at a stage, and you hear actors speak in the actual set, it becomes a completely different thing. The mature cinematographer is one who can interpret these things on the spur of the moment. A spontaneous reaction, to me, is far more important than anything else. You may say, what about the lighting? It’s true the lighting is already there; it’s a question of using it in terms of dramatic content.

“I think the proper word is ‘fee,’ and that comes from you as a person and the awareness of what’s happening in the world today. What has happened in the world thousands of years ago is part of your psyche, which is in the very depths of your soul. All these things come into play and either you’re sensitive to these things or you’re not, and if you are not you are a cinematographer who merely records instead of interpreting. It’s the feel, the know-how; it’s imagination; it’s how you get the best out of nothing.”

“To this day I get letters from all over, wherever it’s being shown, and they want to know how we did this and how we did that...”

The picture was scored by Walter Schumann, who had gained widespread popularity for his work on the Dragnet television series. The unusual music was scored for full orchestra, mixed chorus and solo piano. Much of it was based on Ohio Valley folk tunes and some back-country themes from West Virginia. The Protestant hymn, Leaning on the Everlasting Arms, which figures prominently as a leitmotif sung by the crazed preacher in contemplation of his next outrage, is utilized to fine effect. An RCA recording (1955) of the music, with narration by Laughton, has become a much-in-demand collector’s item.

The Night of the Hunter was too unusual a picture to be very popular in 1955. It was in black-and-white at a time when theaters were demanding color, in standard ratio even though Cinemascope had ushered in a widescreen “craze.” It dared to depict a preacher — albeit one who says his religion is one “the Almighty and me worked out betwixt us” — as a murderer and pervert. This caused censorship problems in several states and resulted in an outright ban in Memphis. As Cortez explains, “It was banned in certain parts of the world because, although here we have many phony preachers, in Europe they don’t have them. There, when you’re a preacher you’re a man of the cloth, you represent the guy above you. They don’t know about these things so they resented seeing a guy in a white collar being a villain.”

James Agee died during post-production. Otherwise, he would have received a heavy dose of the medicine he often dealt out during his years as a film critic. “Reviews were awful here,” Lillian Gish wrote Paul Gregory from New York, adding: “Hope Charles did not read them.” The West Coast reviews were kinder while expressing certain reservations. Variety assessed the picture honestly: “There will be no halfway reactions … Patrons will either like it … or loathe it. While it is a finely acted, imaginatively directed chiller with brooding power, the box office draw … is a debatable matter. The controversy it is bound to stir up will help, but…”

“I think the lack of world acceptance of his picture hurt Charles’ feelings to the point where it got him down,” Cortez says. “He put so much effort into it and the great wit, this great talent Charles had, didn’t, for some reason, come through.”

“However, in contrast to that, in my book the picture was ‘way ahead of its time, which is why it didn’t quite get over. But in later years a kind of cult developed where they had clubs — Night of the Hunter clubs — and it suddenly became one of the “in” things, and as a result it is now more understood and more popular than it was then, because we as a people have a more open mind.”

Tragically, Laughton was never to direct another film. Cortez worked with Laughton and Gregory for nine months in preparation for The Naked and the Dead. “Something happened between Paul and the money men and suddenly the thing stopped. Later, RKO took it over and Raoul Walsh directed it.” Laughton died in 1962.

Time has a way of catching up with pictures that were not quite in step with the fashion of the moment and bringing into focus those virtues that seemed obscure at first glance. So it is with The Night of the Hunter, which has gathered a devoted following of movie lovers who value experimentation above conformity, daring above security, and artistry above mere competence.

“To this day I get letters from all over, wherever it’s being shown, and they want to know how we did this and how we did that, but most of all they want to know on what river was the sequence of the children in the river done, was it back East or where?” Cortez says. “I keep telling them, this is a fine compliment because we did it on Stage 15 at Pathe.

“It was a joy, creating The Night of the Hunter.”

This article was originally published in AC, December, 1982. Some images are additional or alternate. Author George E. Turner later became the editor-in-chief of AC and then the magazine’s historicals editor, specializing in retrospectives.

Turner’s article also included this brief profile on the cinematographer:

Stanley Cortez, current vice president of the American Society of Cinematographers, is one of the screen’s recognized pictorial stylists. His penchant for creating unusual, striking film images has enhanced the work of such directors as Cloud Lelouch, Fritz Lang, Julien Duvivier, Orson Welles, John Guillermin, Sam Fuller and John Huston.

Cortez began his career as a salon photographer in his native New York City, working with Edward Steichen, Pierre MacDonald, Bachrachs’, Walter Scott Shinn and others. His first motion picture assignment was as a still photographer on the Pathe serial The Green Archer. After working at Paramount’s Long Island Studio, he came to the West Coast with his older brother, film star Ricardo Cortez.

He worked at all the major studios, first as an assistant and later as an operative cameraman to such top cinematographers as Arthur Miller, Hal Mohr, Karl Struss, George Barnes, Charles Rosher, Alvin Wyckoff and Ray June. He became a director of photography at Universal at the age of 27. For six years he specialized in filming mystery and action pictures made on 12-day shooting schedules, then was promoted to the spectacular Eagle Squadron. His imaginative lighting on the earlier The Last Express and The Black Cat prompted Orson Welles to request Cortez for his monumental The Magnificent Ambersons. After Flesh and Fantasy, he signed a four-year personal contract with David O. Selznick.

His work on Selznick’s Since You Went Away was interrupted when he became a member of the Army Pictorial Service, U.S. Signal Corps. He worked with Frank Capra on the Why We Fight series, with John Huston on Let There Be Light, and covered the Yalta and Quebec conferences before returning to civilian life.

His many post-war films include Smash Up, The Secret Beyond the Door, Black Tuesday, The Three Faces of Eve and Shock Corridor.

Cortez has received acclaim for his imaginative use of color. Back Street, Blue, The Bridge at Remagen and Another Man, Another Chance are among his most notable color films.

He received Academy Award nominations for The Magnificent Ambersons, Since You Went Away and Smash Up; won the Film Critics of America award for Ambersons; and was the first American to receive the Gold Award of the Societe Francaise de l’Industrie Cinematographe (for The Man on The Eiffel Tower). He has written for Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Two years after the publication of this AC article, a short documentary about Cortez and his work on Night of the Hunter was produced for French television. The cinematographer was interviewed at the ASC Clubhouse:

Night of the Hunter was selected as one of the ASC 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.