General Hospital: The Never-Ending Story

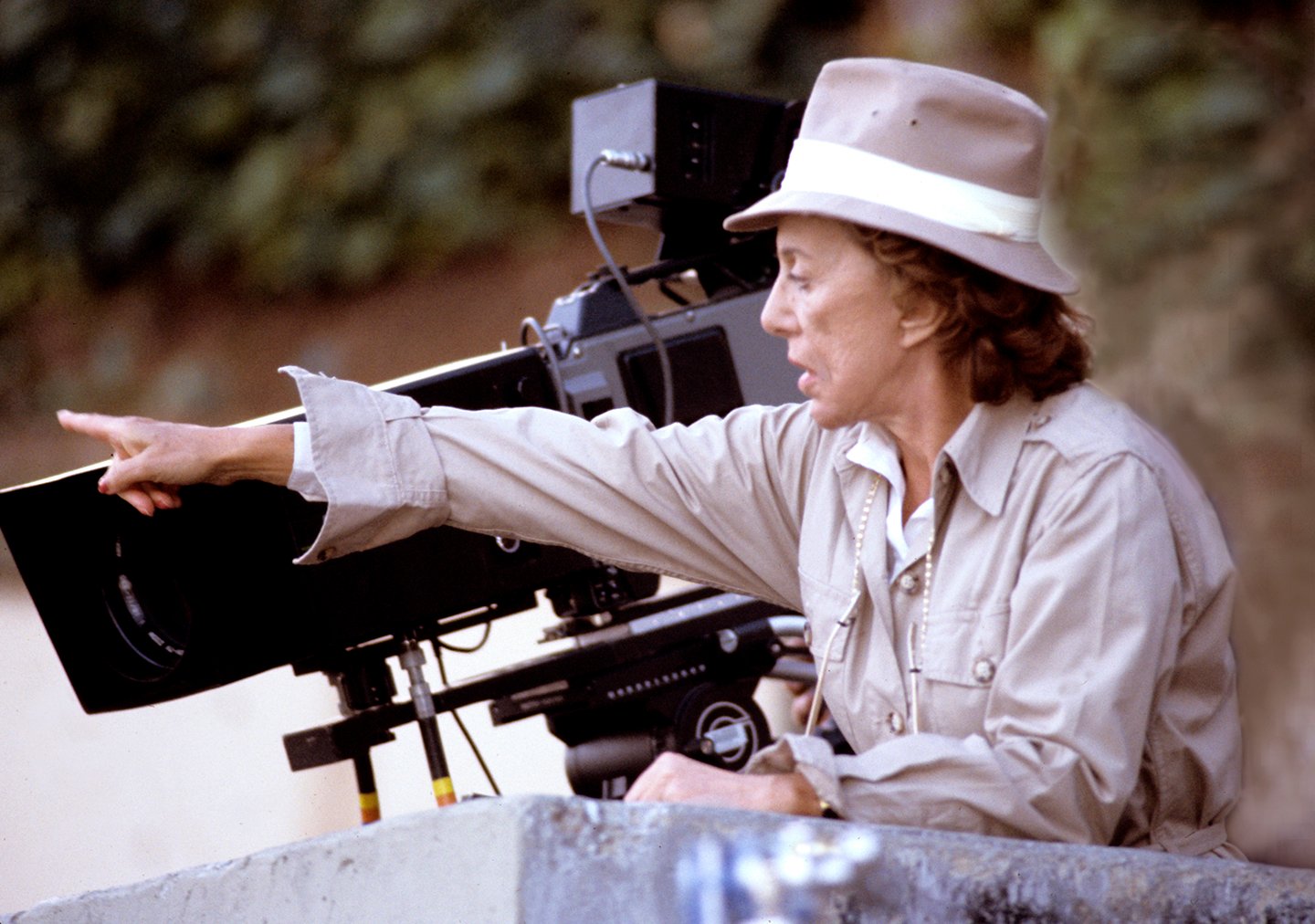

AC visits the set of General Hospital to observe the finely tuned methods and marathon pace of daytime-drama production.

AC visits the set of General Hospital to observe the finely tuned methods and marathon pace of daytime-drama production.

Behind-the-scenes photography by XJ Johnson and Howard Wise, courtesy of jpistudios.com. Additional photography by Erik Hein, Matt Petit and Todd Wawrychuk, courtesy of American Broadcasting Companies Inc. and ABC Photo Archives.

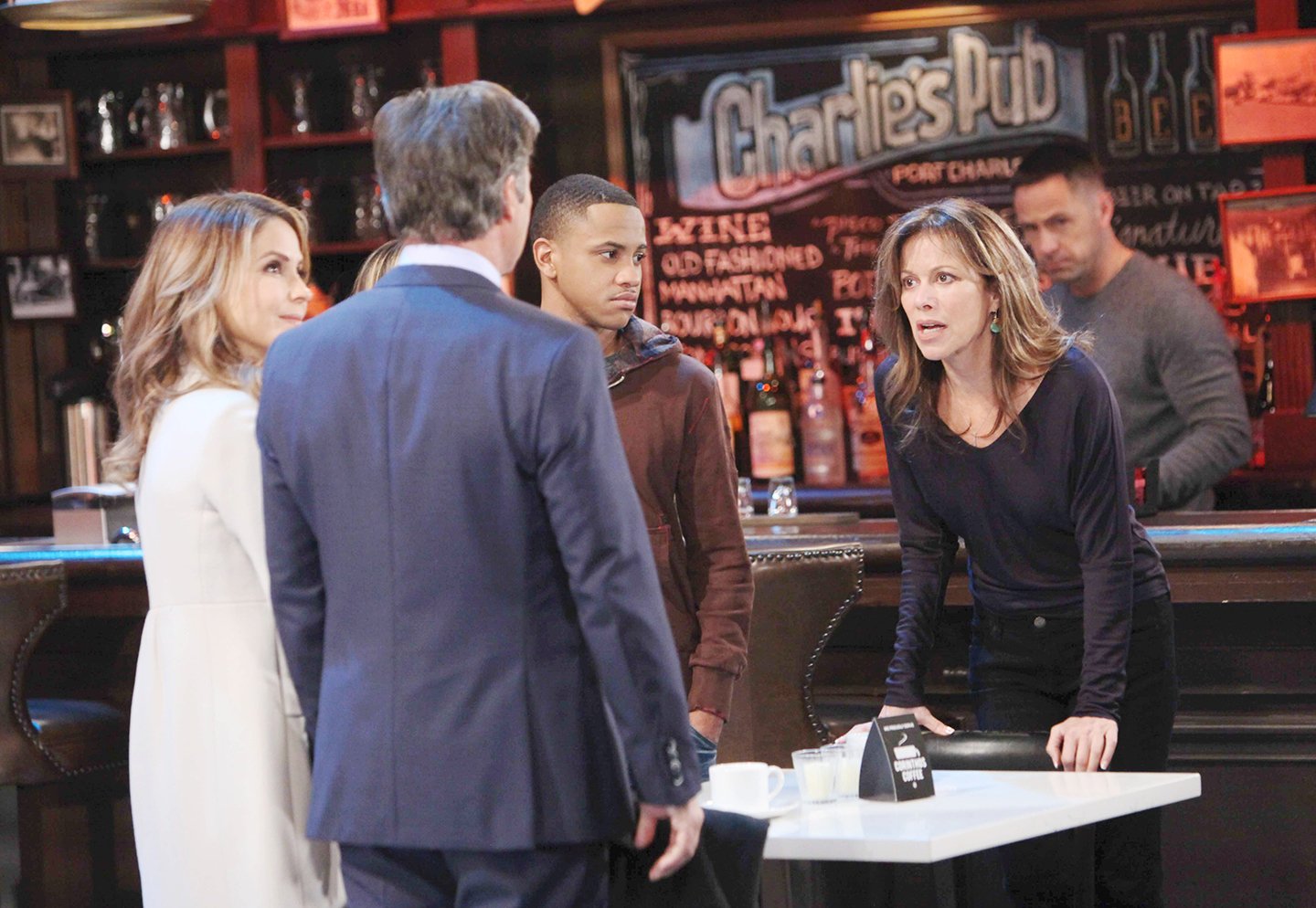

The camera focuses on a computer screen as “Henrik Faison” is typed into the “Spyder-Finder” search bar. No results appear. Cut to Anna Devane (Finola Hughes) sitting on the couch in her dark living room. Her face is illuminated by the glow of her laptop. Cut to a wider, elevated angle that reveals the fire burning in her fireplace as she reaches to grab her glass of red wine from the coffee table. The camera slowly zooms in, right before a cut to a closer shot of Anna as she sips her wine. The camera zooms in further. She is deep in thought when interrupted by the sound of her daughter.

“Mom?” Robin Scorpio-Drake (Kimberly McCullough) calls out. Cut to Robin entering the room.

“Oh, my God — Robin!” Anna exclaims. Cut back to Anna as she sets down her glass of wine and her laptop. The camera tracks her rising from the couch to embrace her daughter.

“What are you doing sitting all alone in the dark?” Robin asks. Cut to Robin’s expression as she embraces her mother. Cut to Anna’s expression during the embrace.

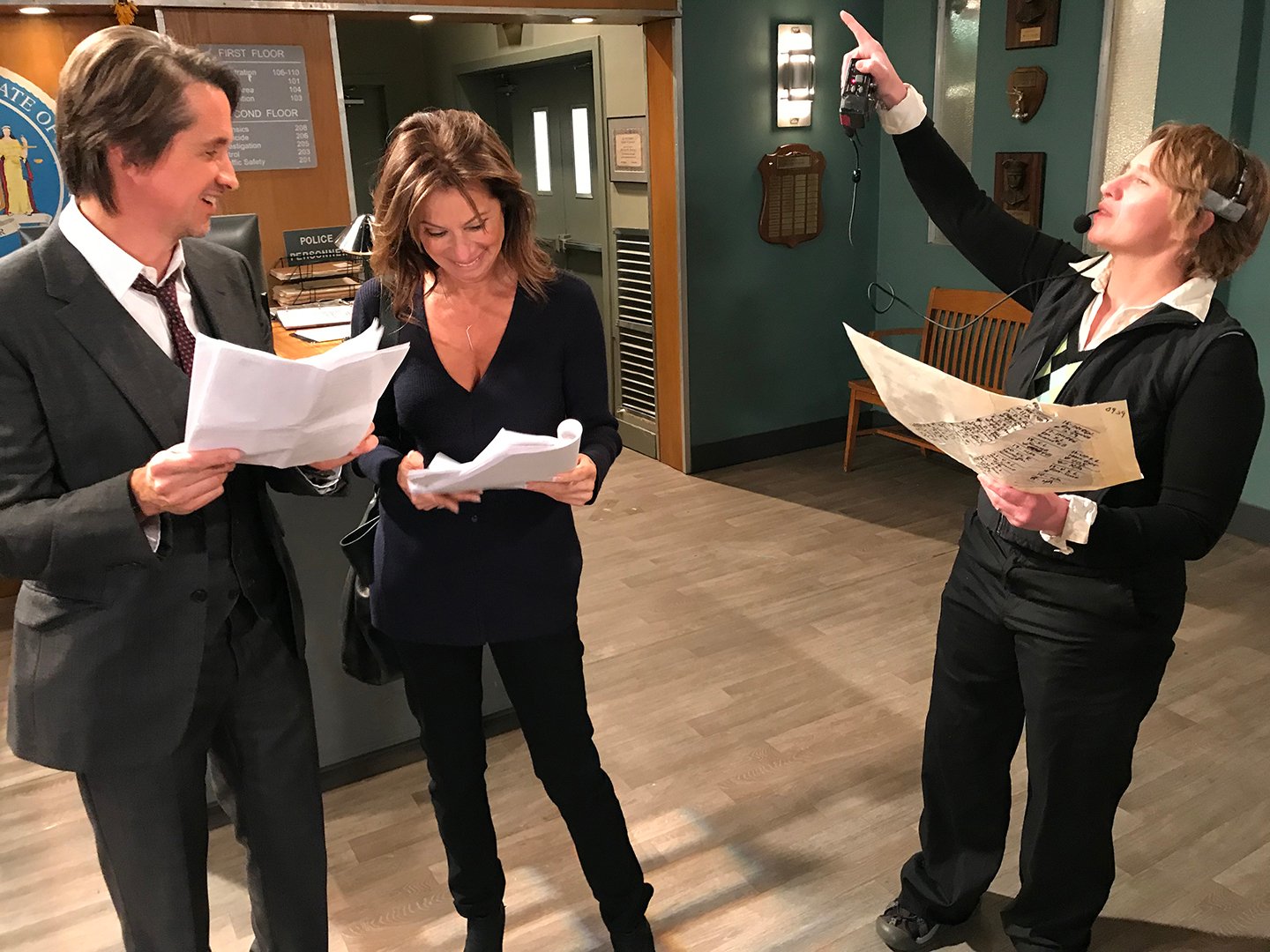

“Cut!” It is the voice of director William Ludel, speaking over the P.A. system from the control booth on the set of the longest-running American daytime drama currently on television, General Hospital — the set of which AC has been invited to visit. We watch as stage managers rush to give the actors direction imparted to them by Ludel through their headsets. The crew quickly resets all equipment to the top marks. Like a well-choreographed dance, all players return to their starting positions to record the scene’s second and final take.

There is a two-monitor display to the left of the set. The top monitor shows the “director’s cut,” which displays the scene as it would appear to an audience, while the bottom monitor is a split-screen showing the feed from all four cameras. This is where we meet producer Mercer Barrows, who serves as our behind-the-scenes tour guide for the episodic production shot at the Prospect Studios in Los Angeles.

The previous incarnation of this particular stage once housed such classic shows as American Bandstand, The Lawrence Welk Show, Let’s Make a Deal and Family Feud, and served as home base for the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. It was torn down and replaced in 1989 with a structure designed specifically for General Hospital. Prospect Studios is the original home of the production, though through the years it cycled to Desilu Studios (now Red Studios Hollywood), followed by Sunset Gower Studios, before returning.

General Hospital first aired on ABC on April 1, 1963. The story focused on Dr. Steve Hardy (John Beradino), chief of internal medicine, and Nurse Jessie Brewer (Emily McLaughlin) as their daily lives played out on the seventh floor of the hospital.

Created by Frank and Doris Hursley, General Hospital was the first daytime medical drama shot on the West Coast, with an original half-hour runtime that expanded to 45 minutes in 1976 and eventually to 60 minutes by 1978. The show airs five episodes a week, 52 weeks a year, and they recorded their 14,000th episode this past February.

“When I started on the show in 1979, I worked in the art department,” Barrows says. “We would shoot one episode a day. Each night, we would prep the stage for the next day, setting up for different scenes and different sets. Now, for cost reasons, we try to complete blocks of scenes without changing the sets. So at the end of each day, we have completed multiple parts of up to three or four episodes.”

To keep up with this type of shooting schedule, there is an extensive amount of planning that goes into each production day, and it is executive producer Frank Valentini who keeps it all running smoothly. “My position is all-encompassing,” Valentini says. “I oversee all of the directors, the look of the show, the casting of the show, and the writing. As the showrunner, I am also in charge of the budget and figuring out how we are going to execute each episode. It is pretty intense, but a lot of fun.”

He further notes that the show’s three lighting directors — Melanie Mohr, Vincent Steib and Bob Bessoir — in large part serve as the production’s cinematographers. To help explain the amount of preparation involved in the daily production schedule, Mohr breaks down the lighting process:

“If I am scheduled to be the lighting director on Thursday, I will report to the studio at 10 a.m. on Wednesday for the Thursday production meeting. The meeting is about an hour long and includes executive producer Frank Valentini, the director or directors scheduled for that day, the booth producer for the day, the art department, the writer, hair and makeup, the prop master, the financial department, production manager Tom Rotolo, and myself — the lighting director. We will go through every single scene scheduled for that day, and talk about whether the scenes are day or night, who is in the scenes, what the feel of the scenes are, which cameras are going to be used, and if they are going to use a high camera or a low camera. I will talk with the director, producer and art department directly. I will look at the blueprint of each set and go through it with the director to find out what the action is, where people are going to stand, and where the cameras are going to be. I’ll put all that in my head and then go home to take a nap, before returning at midnight to join the night lighting crew.

“At midnight, we hit the ground running and start lighting all the scheduled sets,” she continues. “I go through every set, look at the blueprints and the blocking from each director, and I instruct the crew about where to put every light and what gels to use. Then we will move to the next set and do it all over again until all the sets are done.”

The nurses’ station is the only permanent set on stage. There is an estimated total of 200 sets that rotate in and out of the stage’s remaining space. Depending on the scenes planned, the number of sets prepared for a single day of shooting range from two or three to 12 or 13.

Three days a week, construction crews come in at night, along with the electrical crew. Some of the sets, like Kelly’s Diner and the Quartermaine mansion, have been a part of the show for decades — and have been built to be reassembled quickly — while others are created for limited-time use. The latter tend to incorporate materials repurposed from previous sets, and might only stick around long enough to complete a storyline. The location of each set is arranged to maximize stage space. Sets are sometimes built in a condensed version. “Shooting order is determined by degree of difficulty of scenes and cast requirements,” Barrows notes.

For each set, “the head electrician draws a lighting plot as instructed and designed by the lighting director of the day,” Steib says. This plot notes the channel of each fixture, and is later referenced during recording. There are no permanent lighting designs for the individual sets because they are continuously placed in different areas on the stage and are subject to varying story-based requirements.

“All standard rotating sets have a basic ‘look,’” Bessoir says, “but that can change [based on] the type of story we are telling — time of day, dramatic situation, or camera or actor movement. If [the script calls for a] blackout on the show — or a fire! — the source will change.”

Since the job requires a 20-hour workday, the lighting directors rotate, but they do communicate with each other when necessary.

“Communication between the lighting directors is important for continuity, especially when we are establishing a new set,” Mohr says. “The lighting and colors on a set can look vastly different in person than they do on camera, and since we set up the lights hours before the cameras are brought in, it is important that we communicate with each other in regard to what we tried out, so together we can produce the right look and feel for a set.”

When Mohr has the opportunity to establish a set, she uses her background in theatrical lighting as her main inspiration. Her love of horror, science fiction and silent films influence her lighting designs as well. “I borrow a lot of lighting looks from The X-Files,” Mohr relates. “When we had to light the set of an old boiler room in the hospital basement about a year ago, I established it to look like something you would see on that show.”

Mohr also established Anna’s townhouse. Bardwell & McAlister 2K Fresnels are typically rigged high above this set, while Mole-Richardson 2K Fresnels are hung lower to serve as “eye lights, but we also call them hangers or front lights,” she notes. “The Mole-Richardson lights give out the same amount of illumination as the Bardwell & McAlister ‘green-head’ lights, but they are smaller in size so it gives the cameras and boom operators a little more room to maneuver.”

Bessoir adds, “We use 1⁄2 diffusion wraps and modifiers, plus the usual corrective colors. We also use 24-by-32 Chimera Quartz Plus soft banks, in addition to a selection of ‘soft lights’ from 1K to 4K. Theatrical gels are used as well.”

Mohr employs ellipsoidals to simulate window light on the townhouse set. A gas fireplace is installed and run by special effects, and practical lamps are placed by the art department. All lights are run through dimmers, and controlled via DMX with an ETC console by daytime lighting-board operator Peter Canon in a small room located on the fourth floor. There are more than 1,000 60-amp and 20-amp dimmers on the stage.

“The night crews leave at around 8 a.m., and at 8:30 we go on camera,” Mohr says. “The daytime electric crew is now on stage and I take my place inside the production booth. I watch every scene and adjust the light levels accordingly until we wrap for that day. It could be 5 p.m. or it could be 9 p.m. It depends on how many pages are planned for that day.”

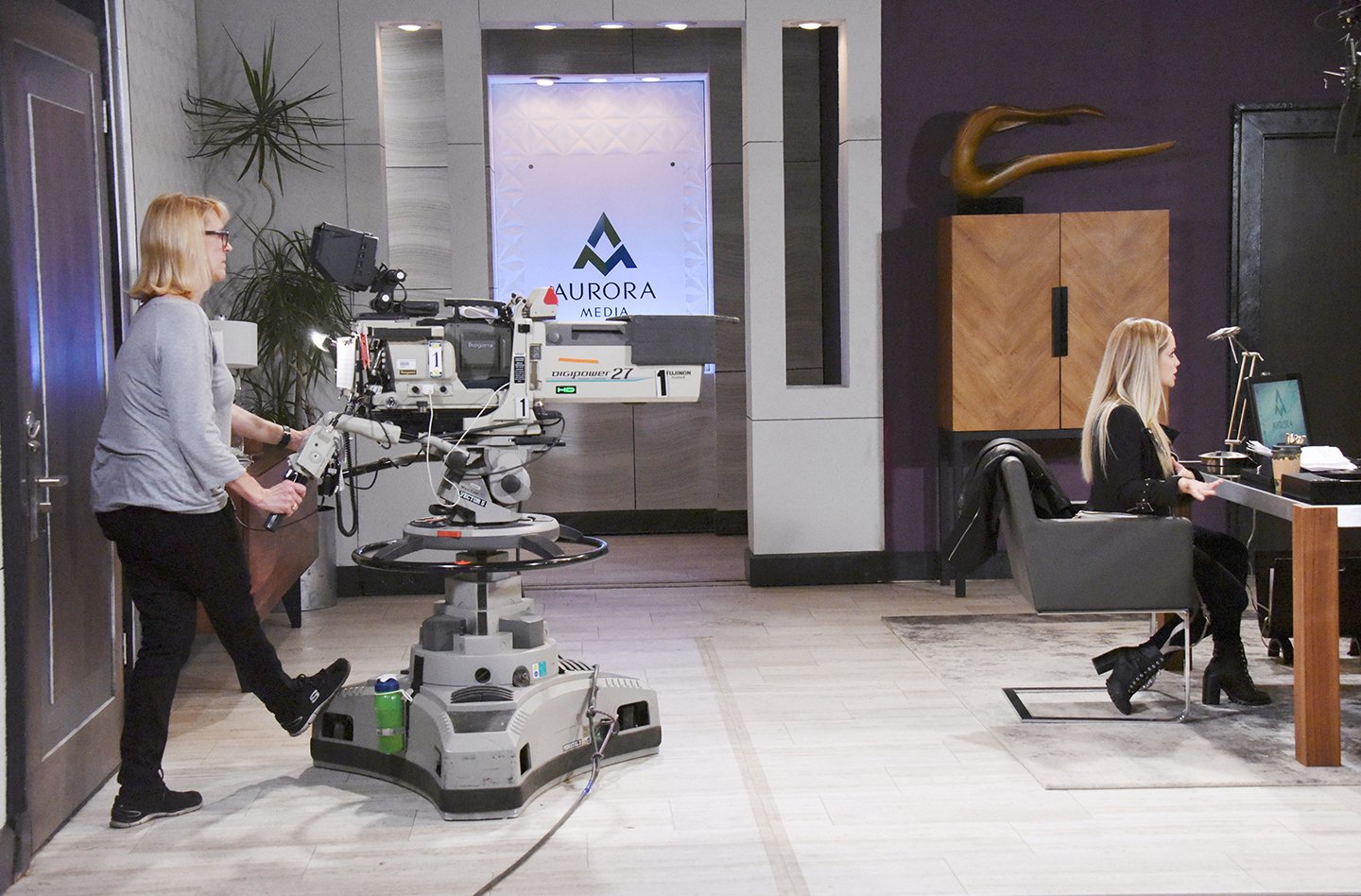

On the day of our visit, production has prepared for a 118-page workday and Bessoir is the day’s lighting director. The scenes we observe are for episode 13,977. Anna’s townhouse is the first set scheduled. Cameras 1, 3 and 4 — Ikegami HDK-79Ds operated by Barbara Langdon, Craig Camou and Dean Cosanella, respectively — are mounted to pedestals and fitted with Fujinon 6.5-180mm broadcast lenses. Dale Carlson operates camera 2, an Ikegami fitted with a Fujinon 4.5-59mm wide-angle zoom and placed on a Vinten Merlin compact pedestal-mounted jib arm, which requires only one operator. “Dale Carlson is the only member of our camera crew who has the ability to use this difficult piece of equipment,” Barrows says. Steib adds that the crew is also ready with “a handheld, and/or a handheld on sticks.”

“We have a constant challenge with lighting a multiple-camera drama series,” Bessoir says. The task, he explains, is to “create a rich dramatic environment [while lighting] for many camera angles at once, avoiding problems with live audio gathering, and [shooting] flattering but dramatic close-ups — at a breakneck pace.”

Video operator Tony Simone notes, “At the start of each day, I move all the cameras to the nurses’ station for chipping and calibration.” As the only permanent set, the nurses’ station “has the brightest light, [so it is used for] gray cards to ensure all cameras have the same white balance.”

Simone controls the camera settings from a console that contains the Ikegami operation control panels (OCPs) for each camera. The console is located in a curtained-off space near the main recording server. With the OCPs, Simone can color correct the image on the fly, and add an ND1 filter for skin tones when needed.

“The cameras have a Black Net and a Soft/FX filter in the filter wheel behind the lens,” Steib says. “Normally the show uses the Black Net, but that can be changed as needed.” The cameras are set to shoot 720p at 59.94 fps and record to Avid DNxHD 145. “We rate the cameras at 340 ASA, and we shoot at a -3dB gain at approximately 20 to 25 footcandles, with a stop ranging from f2.2 to f2.4,” he says.

Bessoir adds, “We try to keep a narrow depth of focus to blur our sets and give a nice close-up look, but we also need enough depth to make focus accurately and fast.”

Clipboards are placed on each camera, with notes containing shot numbers followed by specific directions for the camera operator. Each operator has a different set of notes based on the placement of their specific camera. “They start with number one on the first page of the script,” Langdon says. “Whether or not each shot is coordinated with dialogue or action is decided by the director.”

“On other soap operas like Days of Our Lives and The Young and the Restless, every scene will start on shot number one,” Cosanella adds. “General Hospital is the only one that I know of that numbers them [based on the full script].”

“We have pencils ready so we can write down any modifications or new adds given to us by the associate director,” Langdon continues. “We do have a lot of input as to whether a shot is going to work or not. For example, with [Anna’s townhouse] today, there is one wall off, and a whole second wing of the original set is missing. This setup might not be what they had in mind when it was blocked, so we have to speak up and move some equipment or props to get a better angle to make the shot work.”

Both operators prefer the current fast-paced shooting environment. Cosanella started working on soap operas in 1988 for NBC on the show Santa Barbara. Langdon began her career in 1982, shooting professional sports, and switched to soap operas in 1994 during the baseball strike — starting off on the show Another World.

“I don’t want to go back to the days where it took forever to shoot one scene,” Cosanella attests. “It is exhausting shooting the same thing over and over again.”

“We have to get through 140 pages a day,” Langdon adds. “We don’t really have much downtime, so your energy is up from the start. We shoot a scene once or twice, three times at most, and then we move on to the next one.”

This fast-paced production schedule helps keep costs down and the show on the air. In the late ’70s when General Hospital was on the brink of cancellation, Gloria Monty was hired as executive producer and given a short timeframe to turn the show around — or the world would have said goodbye to the citizens of Port Charles, N.Y. Monty immediately changed the pacing of the program by eliminating the long, drawn-out pauses, and more than doubled the number of scenes per episode. She also redesigned the sets, costumes and storylines to capture the attention of a more youthful, collegiate audience.

On November 16 and 17, 1981, 30 million Americans tuned in to see the wedding of Luke and Laura Spencer (Anthony Geary and Genie Francis, respectively) — which remains the most-watched television event in American soap-opera history. The nuptials took place at the home of Port Charles Mayor John Everett (James Mendenhall), who also officiated the ceremony. The event was shot on location at a home in the Fremont Place gated community located in the Hancock Park area of Los Angeles.

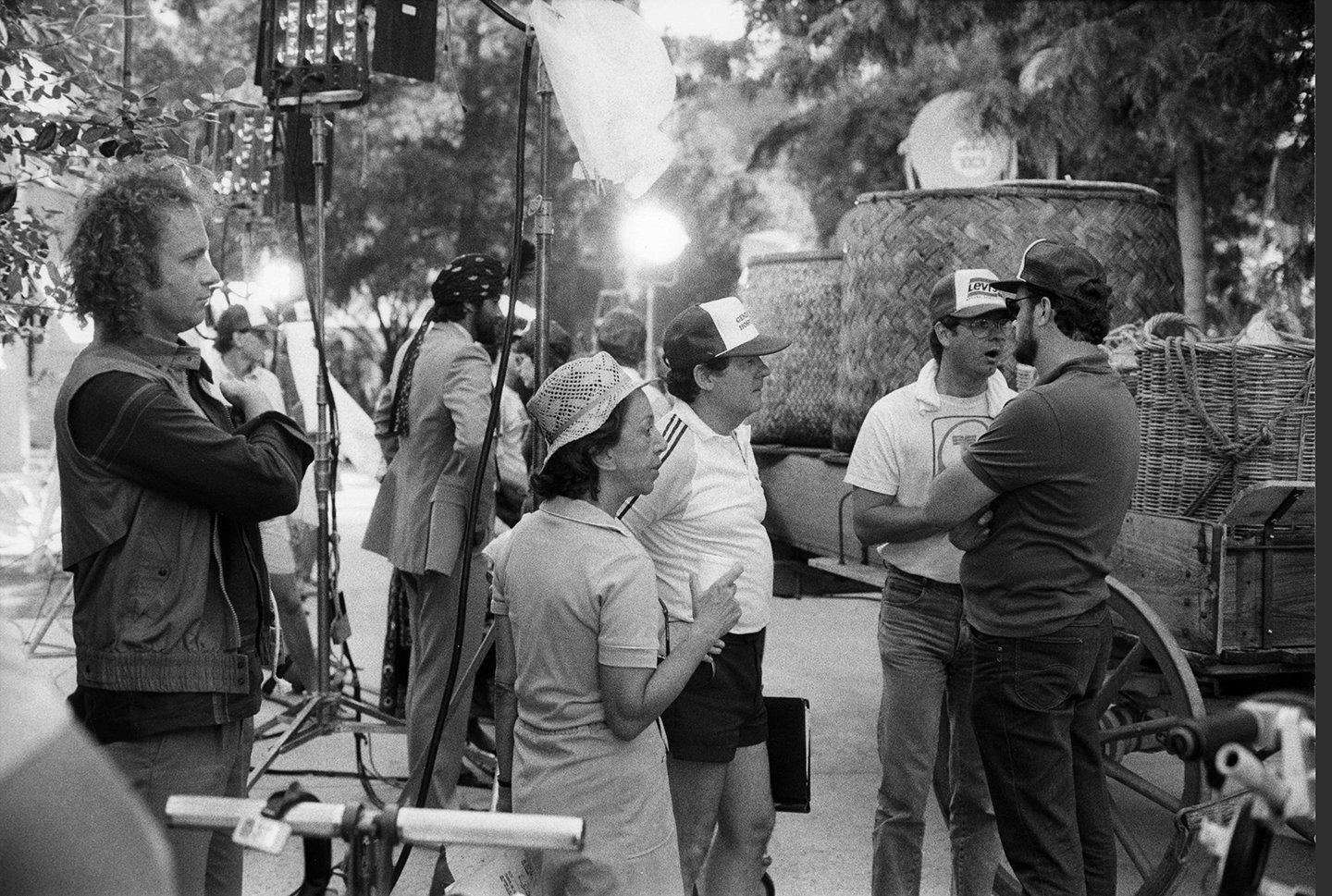

“I was an electrician for the wedding remote, and Thomas Markle was the lighting director,” Steib says. “At the time, they were shooting with Ikegami HL-79A tube cameras. With tube cameras, you had to be really careful not to aim them toward the sun so the tubes wouldn’t burn out. I believe we had four cameras that had triax cable, [which] went back to a video village where each camera had its own tape machine.

“We used 12K and 6K HMIs, and a lot of shiny boards,” he continues. “It felt like we were using miles and miles of cable for this remote. We had 15 electricians working without any meal breaks. When the cast would break for a meal, we had to pre-set the next scene, so we would just grab something while pulling out the cable. Each scene was finished in a couple of takes, and then we were right back to setting up the next scene.”

Shooting on location occurred quite frequently during the 1980s. “I think we maybe did four location shoots a year, and a bunch of mini-shoots,” recalls Hughes, who started on the show in 1985. “We would be out of the studio, out in the open, driving cars and jumping off cliffs, making it look as real as we could.” She explains that Monty was a “real visionary who was amazingly in touch with human emotion, and she wanted everything to come from a real place. Even though we might be doing outlandish stories, everything had to be rooted in a real emotion and be very human.”

Some of the locations included Catalina Island, Santa Barbara, Big Bear Lake, Mexico, Texas and Mount Rushmore. “The show had a lot of money back then,” Steib says, “so if there was something that Gloria wanted to do with the production, they let her do it.”

Actor David Mendenhall, who portrayed Mike Webber, started on the show in 1980 when he was 8 years old. He began as a day player hired by Monty, but his role expanded when his character was adopted by Rick and Lesley Webber (Chris Robinson and Denise Alexander, respectively) — Laura’s parents. He appeared regularly in two to three episodes a week for six-and-a-half years.

“Some tape days were different than others,” Mendenhall recalls. “Some days were called ‘block and tape,’ where we would get our blocking from the director and tape immediately afterward. We would start in the morning and shoot until we were done. However, most days were what we called ‘rehearse and tape.’ When we taped shows that way, we would block and rehearse in the mornings. After rehearsals ended, all the actors would be called in to receive notes from the director and Gloria for the scenes we worked on together. We would start taping those scenes in the afternoon.”

McCullough started on the show in 1985 at the age of 7, with Robin immediately set up as an integral part of the storyline, which was unusual for child actors working on soaps. McCullough worked five days a week with 40-50 pages of dialogue a day, while attending studio school on set, along with Mendenhall.

“Gloria liked to work a scene to death,” McCullough says. “Even though she was the executive producer, she acted more like a director. She had me audition for the role 12 times, and the last three times were improv screen tests to make sure I could improv with Finola Hughes and Tristan Rogers (portraying Robert Scorpio), who played my parents. There was a lot of trying to make it seem like real life, and the scenes felt really natural because we worked the hell out of them. It is very different than it is today, because we had long hours. We would get there at about 6 a.m. and some actors would still be taping until midnight or 1 or 2 in the morning every day.”

These days, the workday for the actor depends on when their scenes are scheduled for recording. McCullough and Hughes note that they often arrive at the studio around 6-6:30 a.m. so they can get through hair and makeup and not have to rush before rehearsal, “unless you are first up, and then you are rushing,” Hughes says.

“The scripts are sent out digitally about a week in advance,” Hughes says. “I read the script as soon as I get it, so if there is something that jumps out to me in a speech or in the dialogue, I will email the producer to see if we can play around with it a little, and they will send me revised pages about a day or two before shooting.”

Once on set, we learn there was a quick rehearsal and blocking with the actors and director at around 7:15 a.m. Per usual, the director then headed to the control booth, where he joined Bessoir, producer Mary-Kelly Weir, production associate Jillian Dedote, associate director Teresa Cicala and technical director Chuck Abate. They now sit facing a wall of monitors. Similar to the monitors on set, the larger one displays the feed with cuts, while the smaller ones are linked to each camera on set.

They start with a technical rehearsal. The production associate monitors the script and keeps track of the overall timing. The associate director gives shot numbers to the camera operators through the headset. Ludel snaps his finger and says the camera number he wants to cut to, and the technical director makes those cuts from the switcher.

In the far-right corner of the room, Bessoir keeps an eye on the lighting. Upon noticing a glare on a picture frame on Anna’s fireplace, he instructs the crew to make an adjustment. He also refers to the lighting plot, and tells Canon — via headset — which channel to adjust, and how much light needs to be reduced, to help eliminate the glare. He also notices a shadow coming from either the boom or the Merlin. He calls for additional adjustments from the crew until the shadow disappears.

The technical rehearsal ends and they start from the top, recording a single take. Everyone looks to Weir for approval. “Looks good,” she says. “Moving on.”

The crew sets up for the next scene, the actors check their scripts, and Ludel quickly runs to set to speak with the actors. When he returns to the booth, the process starts over again. This continues until all scheduled scenes are recorded.

The associate director who was in the booth for that episode will complete the first editing pass with Avid Media Composer, after which postproduction supervisor Peter Fillmore takes over. Fillmore reviews all footage to ensure the best possible cut. He completes the final cut with Valentini before it goes to sound effects, music and coloring. Colorist Stephen Kuns performs final color correction using Blackmagic Design DaVinci Resolve. All deliverables are output to 720p and 59.94 fps, and given to the network where closed captioning is added.

“There are so many wonderful dramas on the air — Grey’s Anatomy, for example — that have borrowed from soap themes,” McCullough says. “I just have so much respect for Frank Valentini and for how he runs his show, because nobody is putting out that type of quality in that amount of time with that amount of money.”

Valentini adds, “People who don’t watch [daytime dramas] are often quick to dismiss them, but I am so proud of everything we do here. We have an incredible team made up of very dedicated individuals. So many have been with the show for a very long time, and they really love what they are doing and are excited about it and care about it and come in every day prepared. It really is like a family.”

TECHNICAL SPECS

| Aspect Ratio | 1.78:1 |

| Stock | Digital Capture |

| Cameras | Ikegami HDK-79D |

| Lenses | Fujinon zooms |

Melanie Mohr started off her career on General Hospital as a stagehand in 2005, with a background in theatrical lighting design. She worked her way up to the position of head electrician — and in January 2016, she became one of three lighting directors on the show.

During AC’s set visit, we asked Mohr to identify a piece of equipment she feels is indispensible for keeping pace with the soap opera’s shooting schedule. “My most valuable asset is my crew,” she says. “We move at a very fast pace, shooting up to 140 pages a day, and it is really important to be surrounded by people who are reliable, think fast and act fast. We have to improvise a lot on the spot, so a crew that can do that, and do it well, is invaluable.

“But if you want an actual piece of lighting equipment that has greatly reduced time cost and the nuisance of running cables, that would be the LED panels by Litepanels,” Mohr continues. “We use 12-by-12s that are battery-operated and handheld — so when a director comes up with a new idea for a shot that we are not currently lit for, we can run in with an LED light panel, put some light on an actor or piece of set, and then continue on with the scene without us having to grab a ladder and rig a new light. The light panels are a really quick, run-in-and-save-the-day kind of instrument, and without these we wouldn’t be able to complete the days, lighting-wise.

“This also speaks to the crew, because they have to run in and stand there with the light panel while the lighting director talks them through the angle and height of where to direct the light. [The lighting directors] have the advantage, because we can see the monitors in the booth, while [the crew] cannot see them on stage. It is important to have a crew that has the right knowledge and instincts to know where to stand on set, and on which side of the cameras.” — Kelly Brinker