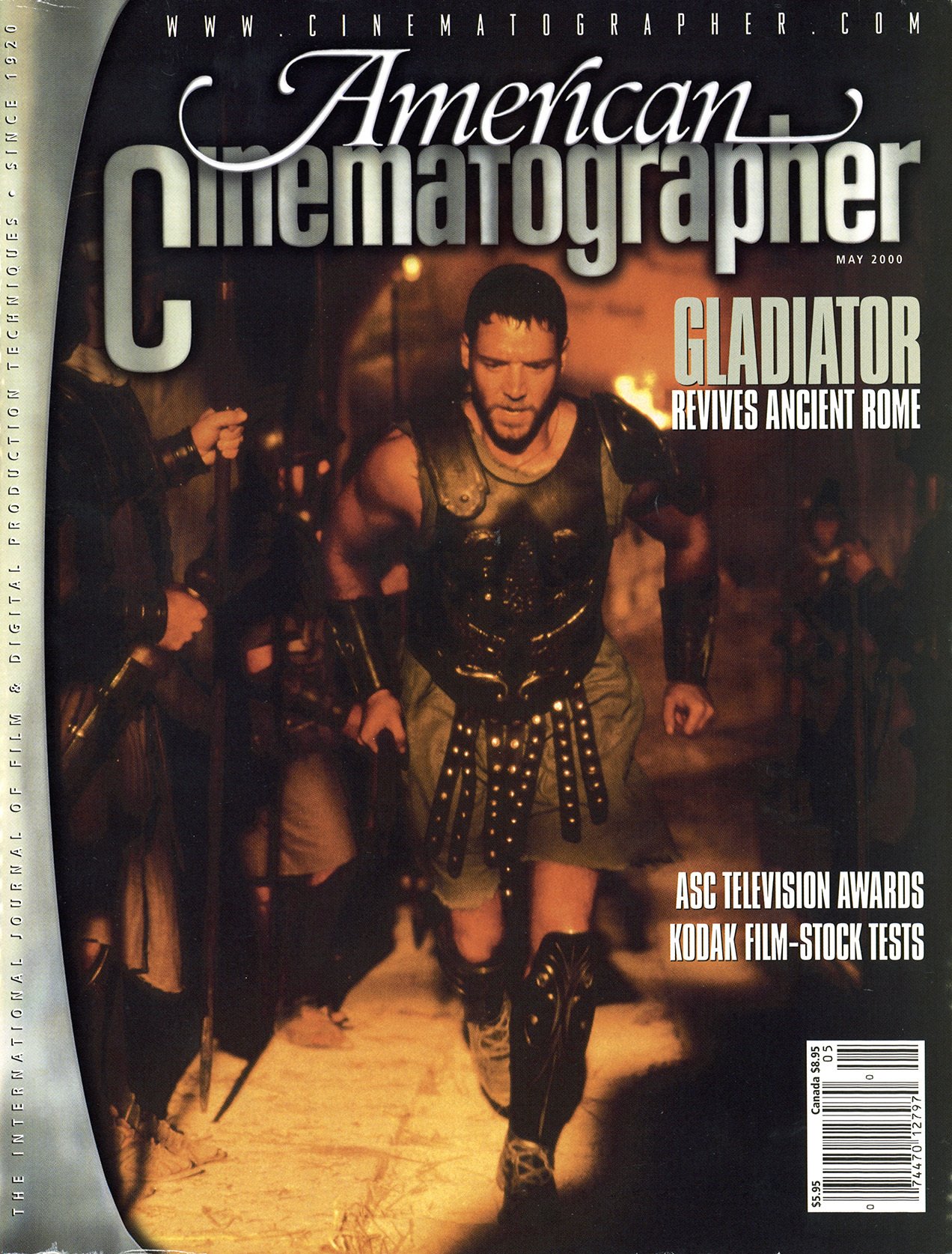

Gladiator: Death or Glory

Director Ridley Scott and cinematographer John Mathieson forge an epic vision of ancient Rome.

According to legend, Romulus and Remus, the twin sons of the war god Mars, laid the foundation of Rome in the Seven Hills near the Tiber River. True to mythological form, Romulus built his own city wall, killed his jealous brother and assumed dominion over the settlement. Thus began the steady rise in power of the remaining brother’s namesake city and the Roman Empire — an empire that lasted more than 1,200 years and ruled much of the known world while surviving maniacal rulers, barbarian invasions and internal upheaval.

The rich history of Rome has been the perfect proving ground for motion picture studios determined to create lavish spectacles. MGM visited this period several times with epics such as Ben-Hur (two versions, in both 1926 and 1959), Quo Vadis (1951) and Julius Caesar (1953). Paramount Pictures produced The Sign of the Cross (1932), Cleopatra (1934), and, many years later, The Fall of the Roman Empire (with Rank in 1964). Rank also produced Antony and Cleopatra in 1973. In 1963, 20th Century Fox put its own version of the Egyptian queen’s life on the big screen with Cleopatra, a decade after the religious-flavored feature The Robe. RKO Pictures laced up the sandals for Last Days of Pompeii in 1935 (which was remade in 1960 by an Italian production company and released by United Artists). Universal also traveled back in time with the 1960 slave-revolt drama Spartacus.

Now, after a drought of more than 25 years, Rome’s brutality and hedonistic delights will be showcased in theaters once again as DreamWorks SKG (with Universal Pictures) takes an epic stab at the genre with the aptly named Gladiator. Following in the historic footsteps of previous studios and their large-scale productions, DreamWorks turned to a reliably masterful director, Ridley Scott, to convincingly re-create the grandeur of ancient Rome.

Gladiator begins as General Maximus (Russell Crowe) leads the Roman legions to victory over hordes of Germanic tribes. A favorite of Emperor Marcus Aurelius (Richard Harris), Maximus is asked by the dying ruler to succeed him in power. In a fit of jealous rage, the unbalanced heir to the throne, Commodus (Joaquin Phoenix), orders the execution of Maximus and his family. Maximus escapes, but he is caught, enslaved and forced into gladiator training — where he must survive a number of savage bouts while plotting his revenge. (Interestingly, the character of Commodus is based on a real historical figure who did lapse into insanity. The unstable emperor renamed Rome the Colony of Commodus — Colonia Commodiana — and actually fought in the gladiator arena himself, imagining that he was the god Hercules.)

For this colossal undertaking, Scott selected British cinematographer John Mathieson, who had photographed several projects for the director’s production houses. Mathieson came up through the traditional camera ranks and worked as an assistant to director of photography Gabriel Beristain for a number of years before the latter relocated to the United States. Mathieson first garnered notice as a cinematographer with a Mardi Gras-seasoned music video for the song “Peekaboo” by Siouxsie and the Banshees. In 1994, he photographed the video "3 Chains o’ Gold" for the artist then known as Prince, the French vérité films Pigalle, and Remembrance of Things Fast: True Stories Visual Lies (directed by John Maybury, with whom he paired again on the experimental Francis Bacon biopic Love Is the Devil; see AC Sept. ’98). For his 1995 French film Bye Bye, he was awarded France’s Legion D’Or and given chevalier status. He has continued to shoot commercials and music videos, including the BMW X5 commercials and No Doubt’s “Ex-Girlfriend” video. He also shot two episodes of the 1997 television series The Hunger, which was produced by Ridley and Tony Scott and starred David Bowie.

Ironically, it was Mathieson’s work with Scott’s son, Jake, on the 18th-century period film Plunkett and Macleane (1999) that caught the keen eye of the elder director. Mathieson and the senior Scott then tried out their synergy on a starkly lit, 1930s-type commercial for the British telephone company Orange. Scott had rewritten the spot for the advertising agency to fit specific locations. “Ridley’s very particular about the way things are, so I had to find my way with him,” says Mathieson. “The standard of craftsmanship that he maintains is very high.”

The duo carried that standard into Gladiator, which was shot entirely on location for 18 weeks. The film opens with the massive battle campaign that the Romans wage against the Germans. Though the filmmakers originally planned to stage this sequence in Slovakia, the production had a stroke of good luck when the British Forestry Commission allocated them an area of forest near Farnham, in southern England; shooting in the forest, which was scheduled for replantation, spared the company a massive move.

Mathieson’s approach to such a large-scale project was to keep the photography as simple as possible. Though Scott initially wanted to film in anamorphic, the Super 35 format was chosen because valuable setup time could be saved by using fewer lights. “Shooting in Super 35 made life so much easier,” Mathieson remarks. “You don’t want a camera kit the size of a room. Working in Super 35, you’ve got a zoom lens and the camera. You can just go.”

The battlefield scenes were shot during the English winter when daylight doesn’t last very long. Out of necessity, Panavision Primo 11:1 and 3:1 zoom lenses were used the most, and multiple cameras were deployed to capture the thousands of extras in combat. “We used [Panavision] Platinums and GII and a bunch of Arri III, and we used an Aaton [XTR] as well,” Mathieson details. “For handheld shots, everyone would scramble for the Aaton because it was lightweight. The focus guys were suspicious of it because it’s light and delicate, but the Aaton was very popular and reliable. That was the camera I used a lot because I knew I could just walk off somewhere with a short zoom and get a shot. [Assistant director] Terry Needham’s logistics were incredible. I would say, ‘Terry, what the hell is going on?’ And he’d say, ‘Well, you’re over here. This is going to happen, so point the cameras that way.’ It was a struggle and a bit of a rush to get through such a big schedule. I would just do what I thought was going to be good in a given situation.”

Having a large arsenal of up to seven cameras at a time allowed Mathieson and Scott to operate periodically, along with A-camera operator Peter Taylor and Steadicam operator Klemens Becker. “Peter’s very good at handheld work; he kind of floats along,” Mathieson testifies. “Klemens’ Steadicam work is very elegant and precise. In those [multicamera] situations, I was thinking, ‘Someone has got to be getting something good.”

Throughout the production, the filmmakers steered more toward a variety of tracking shots (accomplished with dollies and a mobile Giraffe crane mounted with a HotHead II), as opposed to sweeping crane moves. Mathieson submits, “Ridley and I don’t like a lot of high shots. The light flattens out. All of the operators just had to learn to get really strong frames — Ridley Scott-type frames!”

The cinematographer maintains that Scott was quite flexible when it came to getting what he wanted photographically. “We didn’t wait for the light,” he explains. “Look at the opening sequence.

“There’s sun, then there’s clouds, and then there’s smoke. I said, ‘Ridley, it’s f***ing snowing!’ He yelled, ‘Cut! I don’t care.’ At least if you’ve got multiple cameras in that situation, you can get a lot of coverage under one condition.”

Mathieson photographed the battle scenes at various frame rates and with a 45-degree shutter. This technique, employed to great effect for the battle scenes in Saving Private Ryan, helped to make the combatants appear more aggressive and to reveal clear sword movement through the air. “We got into trouble one day with the light towards the end of the battle, so we couldn’t shoot at 45 degrees,” he reveals. “Instead, we shot everything at 8 frames, which gives you two more stops, and printed that back to 6 frames. Then we stretched that back out [to 24 fps]. Of course, each exposure is really long. You’ve got these people swinging swords, and it’s no longer frenetic with all of these sharp edges — you get a far more brushy stroke. The sword becomes almost like a fan as it gets pulled through the air. It worked very well for the scenes in question, which happen as the battle is winding down. The approach wasn’t designed ahead of time, but Ridley is flexible like that.”

The film’s lengthy battle campaign was shot using uncorrected Kodak Vision 200T 5274, and the only filtration consisted of polarizers, which helped to keep things simple while yielding a cold winter look. Much of the blue hue of the tungsten film was taken out during timing sessions at Technicolor in London and Los Angeles. “In London, we got some very nice results from [timer] Keith Bryant, and Dale Grahn did the print [in Los Angeles],” Mathieson says. “We used 5274 and [EXR 50D] 5245, which I often pushed by one stop. The idea was to keep it simple. I used 5274 outside for [scenes set in] Germany, all of the night exteriors and some of the interiors. I would push the 5245 for day interiors or exteriors if it got difficult.”

Adjacent to the charred and muddy battleground was the Roman encampment set, which features the emperor’s large tent as its centerpiece. Mathieson recalls, “In the eave of the tent, we stuck some batten bars, simple light bulbs across the top, which gave off a very low glow. That created an ambiance so the scenes wouldn’t dive into deep black. It was very difficult to rig into. We lit from the floor, basically. We used 5Ks and 10Ks through some heavily diffused Chimeras, and we put Cosmetic Hi-Light and straw [gels] in front of them to give the scenes a candlelit look.”

Two cameras were used whenever possible. Since the motivated sources were oil lamps on stands or tables, the lighting units were placed no higher than eye level. In order to enhance the soft, flame-lit glow, opal and shower-curtain diffusion were added in addition to the gels. A bit of bounce and soft Zap lights were also used, as well as small, hidden Kino Flos to pick up pieces of shiny armor. Those fixtures were gelled with the same colors, but if the Kinos were burning too cold, ⅛ or ¼ CTO was added.

In the encampment’s courtyard, Mathieson went for a less inviting look by replacing his straw gels with L.C.T. Yellow (a light greenish-yellow color), while keeping the Cosmetic Hi-Lights on the 5Ks and 10ks. “It would have been nice to use smaller [lighting] units,” he concedes. “But since we didn’t use very fast stocks — and because we wanted a heavy negative while shooting in Super 35 — we had to stick with those fixtures and even 20Ks in other scenes. We used a Wendy outside in the courtyard to give us a backlight, and we warmed it up with ½ CTO. I didn’t want a cold backlight. I didn’t want the ‘warm candles and a moon’ sort of thing.”

When Maximus is enslaved, he is sold to the School of Proxima, run by the notorious Proximo (portrayed by Oliver Reed, who passed away during production). The company began filming in two Casbahs outside Ouarzazate, Morocco, where production designer Arthur Max built a small, mud-brick gladiator arena. As the gladiator trainees march toward the arena, they travel through a surreal dye market in an alleyway, where raw wool is dyed in bright colors and hung in giant loops to dry. Mathieson recounts, “I took large frames that [gaffer] Roger Lowne made up, and we stretched flame red, deep red and primary red in great bits of 12' by 4' frames, then laid them across the alleyway. We didn’t have to light it — we just let the sun smash through these frames, creating this incredibly intense color. I did, however, have to let some [straight] daylight cut through.”

In Malta, the design team battled terrible winter weather to erect the palace district of Rome, using an old British military fort as a backdrop. As the production design team was finishing the sets, the camera crew was moving in right on their heels. “We left the hot deserts of Morocco for the wet spring of Malta, and we went straight into nights with no pre-light,” Mathieson says. “We just had to hope it was right and that it would work. It would have been nice to have discussed that with Ridley, but he kind of liked it the way it was. All of the Scotts love a bit of chaos, I think.”

Further complicating matters was the fact that the film’s script was undergoing a series of rewrites, which didn’t allow for much pre-rigging. “You never knew what was going to happen or who was going to end up doing what,” the cinematographer laments. “That type of thing drives the crew crazy, especially in terms of lighting. Roger and Peter were good-humored about it, though. They would just say, “Okay, we’re going to do that again.’ That was the beast. That was Gladiator.”

In their approach to the victorious army’s entrance into Rome, the filmmakers took a cue from Leni Riefenstahl’s notorious homage to Adolf Hitler, Triumph of the Will, striving to make the sequence appear starkly desaturated like newsreel footage. Expanding on the fascist motif while discarding the desaturation, Mathieson referenced black-and-white photographs of Nazi chief architect Albert Speer’s foreboding designs to make the emperor’s palace, composed of dark marble and hanging chiffon silks, look similar to the severe, contrasty Reichstag headquarters. “We didn’t use any gels on the lamps,” Mathieson says. “The palace isn’t cold, but it doesn’t have that warmth about it. For both day and night scenes, we used a lot of Leelium balloons — 5Ks that you could switch to 4K HMI sources — because we were seeing the ceiling. You can just pull them in and park them over people’s heads, and they give you a nice ambiance. There was always a lamp burning on a table, so I would try to get a little something in on the actors’ faces — particularly that of Connie Nielson [who portrays Lucilla] — with more Chimeras and some bouncing. I would take some of the top light off her with a flag. When we were doing a close-up, we would also bring the balloon down so that it wouldn’t be so toppy.”

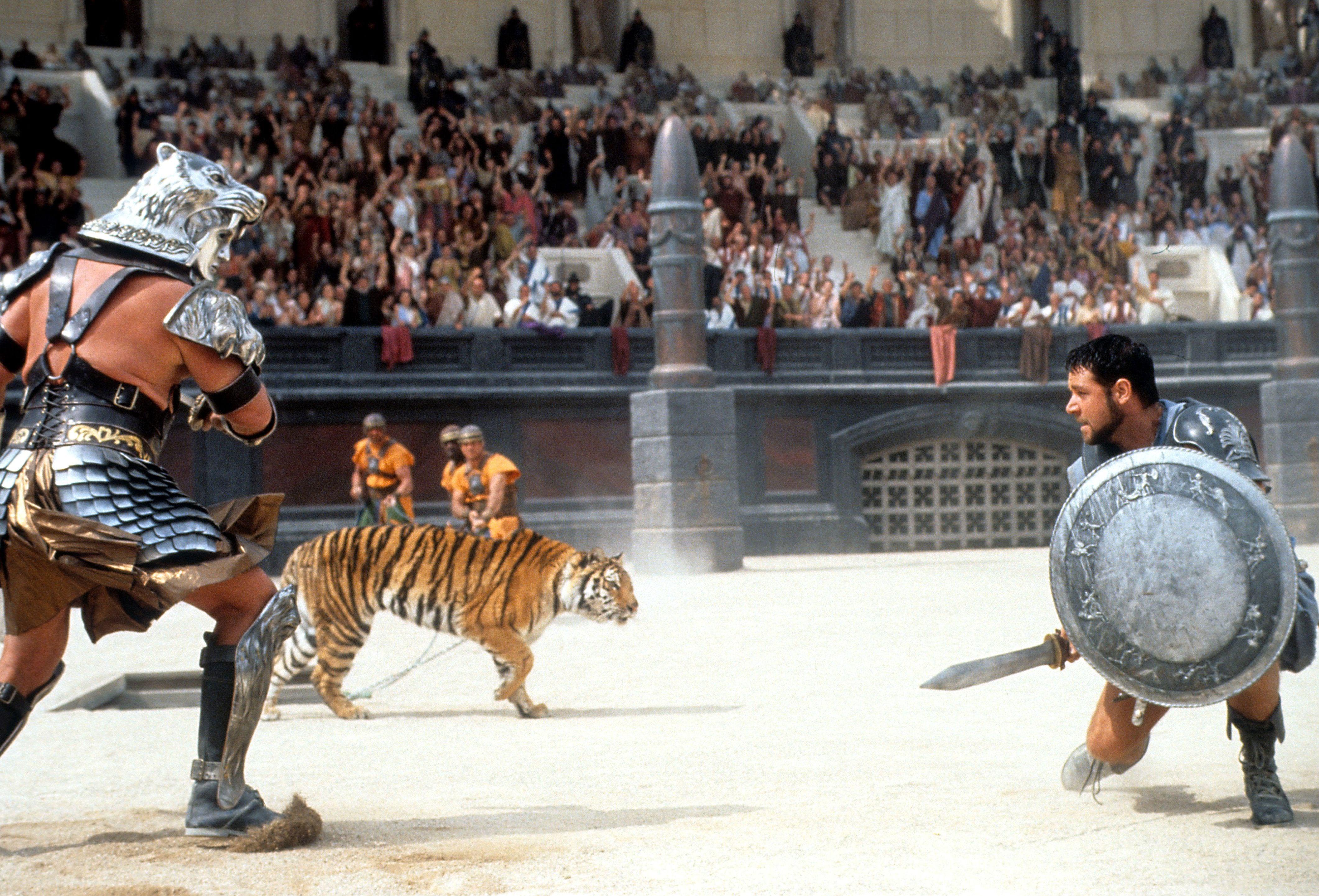

The showpiece of the palatial district is the great Roman Colosseum, where senators and common folk crowd the stands to witness gladiators wielding a variety of weapons against each other — and also against ferocious tigers. A lower portion of the Colosseum was constructed in the form of a “J,” while the rest of the arena and the upper deck was added using computer-generated imagery (CGI) at Mill Film London.

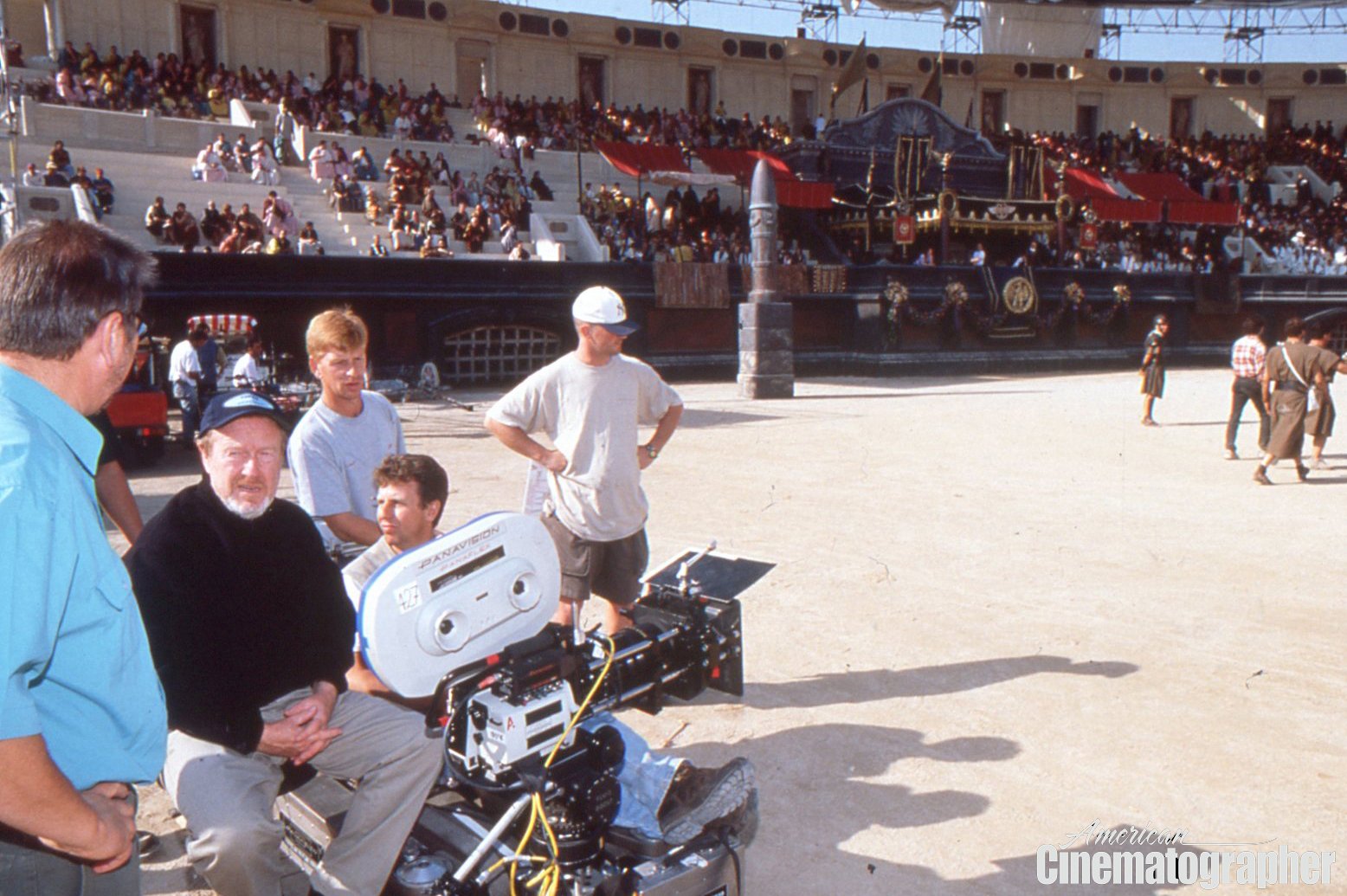

Mathieson and Scott wanted a theatrical balance of light and shadow to play on the Colosseum crowd. Shadow was applied by computer on some test shots, but the results were unsatisfactory. After some investigation, Mathieson approached the architectural engineers Buro Happold — who constructed the Millennium Dome in England — and engineers Peter Heppel and Paul Romain to design a Roman velarium, or awning, thus allowing the practical creation of an accurate shadow. At Shepperton Studios, a small model of the Colosseum set was built, and a 1K lighting unit was placed as far away as possible to simulate the sun. Various shapes were placed on top of the model to determine what would cast the best shadow. This exercise was taken one step further when EuroHappold broke out an old heliostat that displayed on the model how those shadows would track during the day.

camera himself on many occasions, takes a break from photographing a gladiator bout on the Colosseum set in Malta.

“It was the most expensive shadow ever, I think,” says Mathieson, who made frequent use of Sun Path software to predict the sun’s positioning. “The velarium had about 17 of these enormous, trapezoidal shapes, which ran on cables, coming down it. If it hadn’t had those, it would have looked very flat. There were ribbons of light coming through these trapezoidal canvasses, and when we threw smoke and dust up, these shafts came down as very dramatic, long knives of light. If the shadow became too much, the sails were pulled back to allow more sunlight. Ridley’s very aware of where the light will be good, and he’ll support you.” In post, the practical velarium was digitally removed, and the rest of the Colosseum was completed in CGI, including a new, moveable velarium manned by digital, motion-captured slaves.

Though the project was much larger in scale than he is used to, Mathieson took it in stride. “Gladiator was a big step up for me,” he admits, “but I’ve been in those situations before. Having a wonderful crew was a great plus. They worked bloody hard and got things done quickly.”

Mathieson earned Academy and ASC Award nominations for his outstanding work in the picture, among other honors, and was later invited to become a member of the BSC. He would re-team with Scott to photograph features including Hannibal, Matchstick Men, Kingdom of Heaven and Robin Hood. AC most recently covered his work in the gritty superhero feature Logan. He most recently photographed Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, for director Sam Raimi.