Gregg Toland, ASC — An Enduring Legacy

An in-depth look at one of the most influential filmmakers of all time — a true ASC great who elevated the art and craft of cinematography.

The first thought that struck anyone who met Gregg Toland was that he appeared frail, even ill. He had a sallow complexion, was underweight and walked with a stoop that made him appear older than he was. He seemed to be carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders. When he spoke of the thing that dominated his life — cinematography — the melancholy look vanished. No one could speak more eloquently or knowledgeably or with more enthusiasm. When he was at work, an even greater change took place: He was a dynamo of energy to whom long hours and difficult working conditions meant nothing.

Toland was one of the outstanding cinematographers because he possessed a rare combination of skills, a natural artistic instinct, a determination to deliver the best product of which he was capable and an enormous capacity for work. All of his work is that of a young man, because his life was tragically brief. His advice to aspiring cameramen was simple.

“Forget the camera. The nature of the story determines the photographic style. Understand the story and make the most out of it. If the audience is conscious of tricks and effects, the cameraman’s genius, no matter how great it is, is wasted.”

He was born May 29, 1904, in Charleston, Illinois. In 1919 he was working as a messenger boy at the William Fox Studio at Sunset and Western in Hollywood. One day he looked up at a cameraman on a high parallel, hand-cranking a Bell and Howell. He decided then that was what he wanted to do. Until that moment he had felt no interest in photography. In a matter of months he became a camera assistant, receiving a raise in pay from $12 a week to $18. His boss was first cameraman on the Al St. John comedies.

The cinematographers at Fox considered him the best assistant on the lot. He worked hard, was bright and dependable, and he stayed nights to polish the camera and lenses. His pay leaped to $60 a week — more than twice what the other assistants were making. He assisted top Fox cinematographers such as Daniel B. Clark, ASC, who photographed the Tom Mix pictures and Mix was the highest paid actor in Hollywood.

In the mid-Twenties Toland became second cameraman to another outstanding cinematographer, Arthur Edeson, ASC. A short, wiry man who earned the nickname “Little Napoleon,” Edeson had a fondness for shooting from well below eye-level and building strong, deliberately angular compositions. One of the pictures on which Toland worked with him was The Bat (1926), an artistic comedy-mystery directed by the eccentric Roland West and filled with low-angle shots and gigantic shadows. Edeson’s influence upon Toland was profound. The settings were designed by William Cameron Menzies, who would be a frequent collaborator — and strong influence — in many of Toland’s future ventures.

In 1927, Toland was seconding George Barnes, ASC, another leading cinematic stylist. Among the films on which he assisted Barnes were several Samuel Goldwyn productions, including The Devil Dancer (1927) with Gilda Gray (an exotic dancer from the stage) and The Rescue (1929) with Ronald Colman.

In Goldwyn’s This Is Heaven (1929), an early sound comedy-romance which had a synchronized musical score by Hugo Riesenfeld and several sequences with dialogue, Toland received screen credit with Barnes. He also signed a contract with Goldwyn as director of photography with a salary guarantee of $13,000 per year. The Barnes-Toland team were loaned out to Joseph Kennedy and Gloria Swanson to photograph The Trespasser (1929).

Menzies designed and Barnes and Toland photographed one of the most important early “talkies” for Goldwyn: Bulldog Drummond (1929), with Ronald Colman. If any picture of the era could be said to justify talking pictures as the dominant form of theater at a time when their future was in doubt, Bulldog Drummondwas it. It had all the photographic artistry of the silent films and outstanding shot-by-shot production design by Menzies. The sound and dialogue seemed as natural as the visuals, and the awful camera stasis that plagued most talkies of the period was nowhere evident. One reason was that Barnes and Toland had designed a “blimp” to silence the camera so that it would not have to be housed in an “ice box” (a heavy, soundproof booth from which primitive talkies were photographed). Other cinematographers were working out ways to silence cameras at the same time (at MGM they were wrapping them in quilts), but the blimp became the standard method.

Other Barnes-Toland collaborations followed at Goldwyn’s Studio, the United Artists lot on Santa Monica Blvd. Four of them starred the increasingly popular Ronald Colman: Condemned (1929), Raffles (1930), The Devil to Pay (1931) and the beautifully atmospheric The Unholy Garden (1931).

Toland began working without a co-photographer in 1931, both at Goldwyn’s and on loan-outs to MGM, Warner Bros. and several of Goldwyn’s fellow United Artists members. Among his assignments for Goldwyn were the Technicolor musicals starring Eddie Cantor and the Goldwyn Girls: Whoopee!(1930), with added photography by Lee Garmes, ASC, and color direction by Ray Rennahan, ASC; Palmy Days (1931), The Kid From Spain (1932) and Roman Scandals (1933). All of these were made in the old two-color system, which was effective where absolute realism was not essential. Toland disliked working in color, not only because of the limitations of the process but because he preferred to work on more heavily dramatic subjects. At that time, color photography was usually restricted to musicals.

He also was opposed to the “star system” which reigned at the major studios. He had felt that his work on three Gloria Swanson pictures was compromised by the necessity of catering to the glamorous star’s appearance rather than the general atmosphere demanded by the stories. He received another overdose of glamour on three pictures with Goldwyn’s Russian dramatic star, Anna Sten &mdash Nana, We Live Again (both 1934) and The Wedding Night (1935). A fine actress with unusual but attractive features, Miss Sten was a box-office flop, not only because her heavily accented dialogue was unintelligible to American audiences but because Goldwyn put her in arty, pretentious pictures.

“The star system has us making pictures with personalities rather than stories, sacrificing everything in order to keep some old bags playing young women,” Toland said.

At Goldwyn, Toland had a situation that was the envy of other cinematographers. Generally, cinematographers were — and still are — forced to work on most pictures with little or no preparation. Goldwyn put Toland onto the pre-planning team with the director and designers as much as six weeks in advance. Between pictures he was able to work in Goldwyn’s experimental lab, devising new lenses, filters and camera gadgets. He was aware of the advantages of his situation and often expressed a wish that his colleagues could work under similar conditions.

Nevertheless, much of his loan-out work is first-rate. Public Hero No. 1 (MGM, 1935) is a hard-bitten gangster film which is unjustly forgotten. Les Miserables (Twentieth Century-United Artists, 1935) is one of the most atmospheric of Toland’s films, with a chase through Paris sewers unsurpassed even by the various editions of The Phantom of the Opera. When Chester Lyons, ASC, died early in the production of Mad Love (MGM, 1935), Toland finished the job superbly with no advance preparation. His avowed fondness for the Germanic lighting of the 1920s was ideal for this picture, which was directed by one of the great German cinematographers, Karl Freund, ASC. The Road to Glory (Twentieth Century-Fox, 1936). Howard Hawks’ penetrating look at cowardice and redemption in the trenches, received a stark, cruelly realist treatment at Toland’s hands. Walter Wanger’s unusual History Is Made at Night (United Artists, 1936), gave the cinematographer the difficult task of combining a light romantic mood for a Parisian affair between Charles Boyer and Jean Arthur, some weird atmosphere for Colin Clive as Arthur’s insane husband, and a spectacular treatment for a shipwreck.

During the same period on his home lot, Toland made such notable films as The Dark Angel (1935), Splendor (1935), These Three (1936) (one of his personal favorites), and about half of Come and Get It! (1936), among others.

Dead End (1937), photographed on a gigantic indoor set of a New York slum that is a vastly expanded version of the one Norman Bel Geddes designed for the stage play, is a fine example of the creation of cinematic truth that transcends literal reality. For The Goldwyn Follies (1938), Toland provided some of the best work yet done in the improved three-strip Technicolor. Kidnapped (1938), made on loan-out to Twentieth Century-Fox, captures the spirit of Robert Louis Stevenson’s sinister adventure yarn better than any of the other versions.

Goldwyn’s Wuthering Heights (1939) is an important milestone in Toland’s burgeoning career. He described it as “a soft, diffused picture, a fantasy.” it is filled with candlelight effects, romantic close-ups, waving heather, swirling snow and mist. The picture also has its grim side, calling for low angles, dark shadows and occasional deep-focus shots.

Intermezzo (Selznick International, 1939), despite its soap-opera plot, became famous as the American film debut of Swedish actress Ingrid Bergman. The actress was rather large-bodied at a time when petite actresses were the norm, so Toland concentrated on exquisitely lighted close-ups that captured the natural freshness of an actress who was still a star when she died some 43 years later.

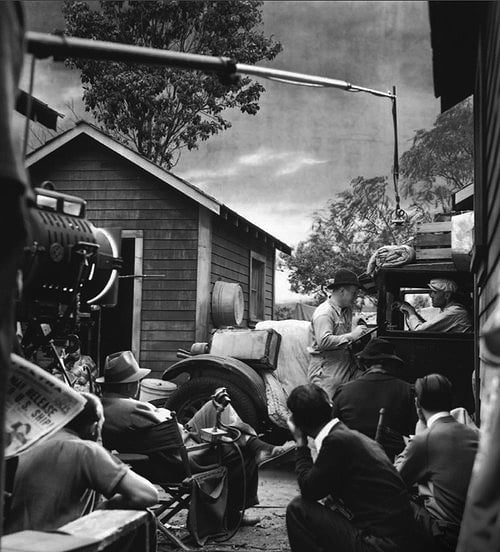

In The Grapes of Wrath (Twentieth Century-Fox, 1940), John Ford’s realist production of the then-controversial John Steinbeck novel, Toland’s photographic style matched the stark, hard quality of the writing. He used no scrims or filters to soften the harsh images of seamed faces, bleak backgrounds and sun-baked dryness that so eloquently illustrated the plight of migrants from the Dust Bowl heading toward California in the Thirties. There is no romance or mystery even in the night effects — just cold, sharply delineated reality.

The Westerner (1940), one of Goldwyn’s rare Westerns, has a monumental, highly scenic look rendered in sharply detailed shots. Great use is made of backlighted dust, long shadows and sere textures. The beauty of the photography was enhanced in the original release prints by sepia toning and highlight tints.

Still the most artistic of Toland’s pictures is The Long Voyage Home (Wanger, 1940), a poignant look at the lives of merchant seamen and the beginning of World War II, directed by John Ford. Most of the film takes place aboard ship, which is simulated on a soundstage. There is no suggestion of limitless horizons or open skies, only the small, cramped world of men who live on cargo ships. The tight compositions are carefully arranged, reminiscent of the groupings in Dutch genre paintings. The details of metal, rust and sweat are as eloquently emphasized as the strong features of a great character cast (John Wayne, Thomas Mitchell, Ward Bond, Ian Hunter, Barry Fitzgerald, Wilfrid Lawson, John Qualen). It is likely that Toland’s fame would rest largely on The Long Voyage Home, but another loan-out, this time to RKO-Radio, resulted in the picture which virtually eclipsed his earlier efforts.

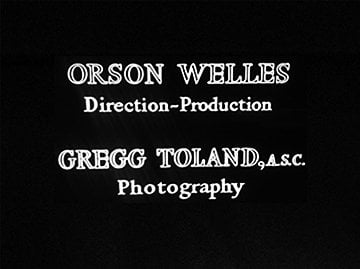

Toland’s most celebrated — and most controversial — film is Citizen Kane (1940), which marked the feature directorial debut of a young man from radio and the theater, Orson Welles. A part of the controversy surrounding the picture was generated by an antipathy toward Welles by many industry veterans, who understandably felt that the last thing Hollywood needed was one more “boy wonder.” One noted wit at the RKO-Radio studio remarked, as Welles strolled past, “There, but for the grace of God, goes God.”

The press was generally unkind, although they lavished a great deal of attention on Welles’ mysterious project at RKO, which at various stages was expected to be an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” and a thriller called The Smiler With a Knife. When gossip columnist Louella O. Parsons learned that Welles’ picture would be about a millionaire newspaperman who built a fabulous castle and collected tons of statuary from all over the world, Hearst Enterprises banned mention of Welles or his production in Hearst newspapers and King Features’ syndicated columns.

When Citizen Kane at last was released, the subject matter aroused less controversy than its visual and aural aspects. The general public despised the picture because it seemed “freakish” with its startling compositions, unexpected sounds and generally unorthodox approach to storytelling. Many cinematographers objected to its eclecticism, feeling that it eschewed the pictorially beautiful techniques that had evolved over several decades to return to the old ideal of crisp, detailed images.

It seems incredible today that this much-admired favorite of television and the revival theaters could ever have been controversial, so completely has its style been absorbed into the mainstream of filmmaking. Its startling transitions and eccentric camera angles seem smooth and realistic when compared to the jump-cutting, fast-zooming cinematography of many films of the past two decades. The lighting effects that once seemed extreme have long since been basic to the so-called film noir style which came to fore during the mid-Forties. Yet the initial showings of the film brought hostile reactions from many viewers. Theater owners were plagued by walkouts and refund demands.

The basic photographic style of Citizen Kane is one of extremely deep focus, a technique Toland called “pan-focus.” There had been earlier examples of the principle, most notably in the 1931 Fox productions, Trans-Atlantic, photographed by James Wong Howe, ASC. Toland, who had more sophisticated tools at his disposal, was able to carry the technique to even more startling extremes.

“During recent years a great deal has been said and written about the new technical and artistic possibilities offered by such developments as coated lenses, super-fast films and the use of lower-proportioned and partially ceiled sets,” Toland wrote in American Cinematographer for February 1941. “Some cinematographers have had, as I did in one or two productions filmed during the past year, opportunities to make a few cautious, tentative experiments with utilizing these technical innovations to produce improved photo-dramatic results. Those of us who have, I am sure, have felt as I did that they were on the track of something really significant, and wished that instead of using them conservatively for a scene here or a sequence there, they could experiment free-handedly with them throughout an entire production.

“In the course of my last assignment, … Citizen Kane, the opportunity for such large-scale experiment came to me. In fact, it was forced upon me, for in order to bring the picture to the screen as both producer-director Welles and I saw it, we were forced to make radical departures from conventional practice…

“Citizen Kane is by no means a conventional, run-of-the-mill movie. Its keynote is realism. As we worked together over the script and the final, pre-production planning, both Welles and I felt this, and felt that if it was possible the picture should be brought to the screen in such a way that the audience would feel it was looking at reality, rather than merely at a movie.

“Closely interrelated with this concept were two perplexing cinetechnical problems. In the first place, the settings for this production were designed to play a definite role in the picture — one as vital as any player’s characterization. They were more than mere backgrounds: they helped trace the rise and fall of the central character.

“Secondly — but by no means of secondary importance — was Welles’ concept of the visual flow of the picture. He instinctively grasped a point which many other far more experienced directors and producers never comprehend: that the scenes and sequences should flow together so smoothly that the audience would not be conscious of the mechanics of picture-making…

“Therefore, from the moment the production began to take shape in script form, everything was planned with reference to what the camera could bring to the eyes of the audience. Direct cuts, we felt, were something that should be avoided wherever possible. Instead, we tried to plan action so that the camera could pan or dolly from one angle to another whenever this type of treatment was desirable. In other scenes, we pre-planned our angles and compositions so that action which ordinarily would be shown in direct cuts would be shown in a single, longer scene — often one in which important action might take place simultaneously in widely separated points in extreme foreground and background.

“These unconventional set-ups, it can readily be seen, impose insurmountable difficulties in the path of strictly conventional methods of camerawork … they simply cannot be done by conventional means. But they were a basic part of Citizen Kane and they had to be done.”

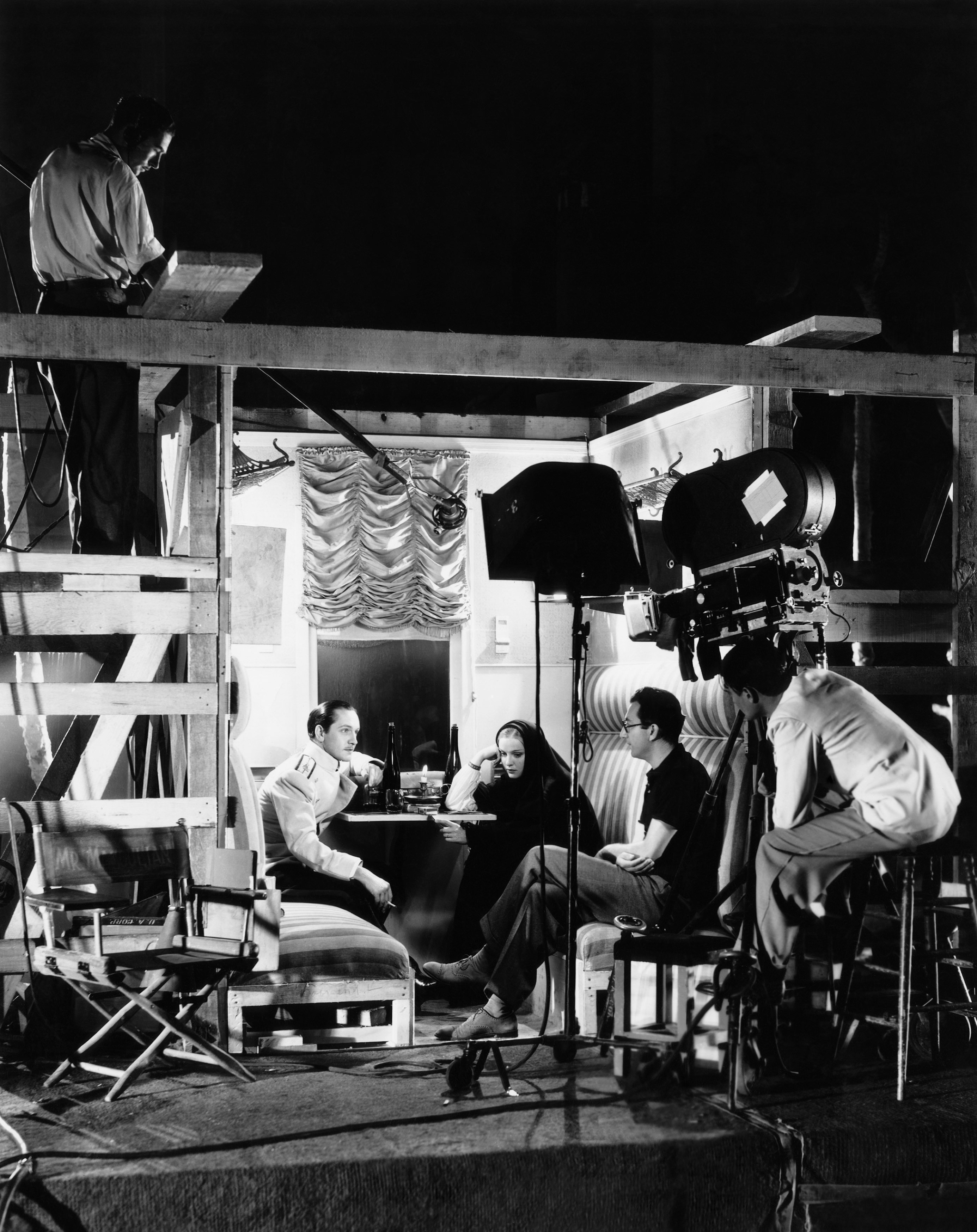

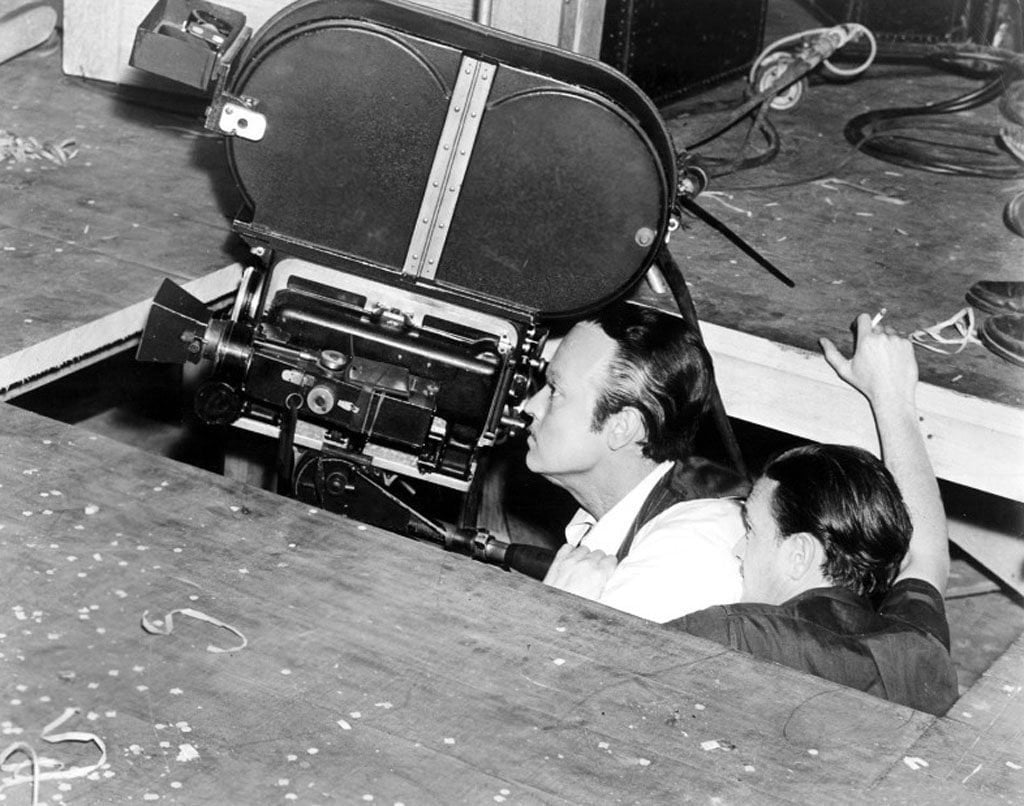

Alfred S. Keller, ASC, remembers visiting the Kane sets at the RKO-Pathé Studio and was surprised at their unorthodox construction. “Some of them were built on parallels instead of on the floor of the stage. They could take up sections of the flooring and set the cameras at floor level or below.”

With much of the picture being photographed from low angles, ceilinged sets were a necessity. Toland said that, “In almost any real-life room, we are always to some degree conscious of the ceiling. In most movies, on the other hand, we see the ceiling only in extreme long-shots — and then it is usually painted in as a matte-shot. In the closer angles, the camera seldom shows the ceiling, or even anything suggesting it. On the contrary, conventional interior lighting effects, since the light is projected from spotlighting units perched high on the lamp rails parallelling the sets, come from angles which would be definitely impossible in an actual, ceiled room…

“Furthermore, many of our camera angles were planned for unusually low camera-setups, so that we could shoot upward and take advantage of the more realistic effect of those ceilings … not one of the 100 sets was paralleled for overhead lighting. With the exception of a few occasional shots for which we could remove a small section of ceiling to permit using a junior or similar spotlight, overhead for really necessary backlighting, everything in the picture was … lighted from the floor.

“With deep sets, this necessitated the use of light with great penetrating power. This was found in the twin-arc broadsides developed for use in Technicolor. These lamps formed the backbone of our lighting, supplemented of course with juniors, seniors and 170-amp, arc spots …”

The ceilings were made of muslin, which made it possible for the sound men to place their mikes above the ceilings, which, in Toland’s words, “eliminated that perpetual bane of the cinematographer — microphone shadows!

“The next problem was to obtain the definition and depth necessary to Welles’ conception of the picture. While the human eye is not literally a universal-focus optical instrument, its depth of field is so great, and its focus-changes so completely automatic that for all practical purposes it is a perfect universal-focus lens.

“In a motion picture, on the other hand, especially in interior scenes filmed at the large apertures commonly employed, there are inevitable limitations. Even with the 24mm lenses used for extreme wide-angle effects, the depth of field — especially at the focal settings most frequently used in studio work (on the average picture, between 8 and 10 feet for the great majority of shots) — is very small. Of course, audiences have become accustomed to seeing things this way on the screen, with a single point of perfect focus, and everything falling off with greater or less rapidity in front of and behind this particular point, but it is a little note of conventionalized artificiality which bespeaks the mechanics and limitations of photography …

“Now it is well known that the use of lenses of short focal length tends in itself to increase the depth of field. So, to, does stopping down the lens.

“Since the introduction of today’s high-speed emulsions, some photographers and some studios make it a practice to take advantage of the film’s speed by stopping their lenses down to apertures as low as f:3.5 or thereabouts when filming interiors …

“To solve our problem, we decided to carry this idea a step farther if using a high-speed film like Plus-X and stopping down to f:3.5 gave a desirable increase in definition, wouldn’t it — for our purpose, at least — be a still better idea to employ a super-speed emulsion like Super-XX and stop down even further? …

“The next step inevitably was to stop down to whatever point might give us the desired depth of field in any given scene, compensating for the decreased exposure-values by increasing the illumination level.”

Toland credited the use of lenses treated with the Vard Opticoat non-glare coating and the use of arc broadsides as the basic lighting equipment with making it possible to photograph interiors at f.8, f.11 and f.16. At these apertures, “... the standard 50mm and 47mm objectives … have tremendous depth of field … Wide-angle lenses such as the 35mm, 28mm and 24mm objectives … become to all intents and purposes universal-focus lenses.”

An unusual innovation achieved through lighting was the transitional lap-dissolves, in which the backgrounds dissolved before the players in the foreground did. “This is done quite simply, by having the lighting on set and people rigged through separate dimmers,” Toland explained. “Then all that is necessary is to commence the dissolve by dimming the background lights, effectually fading out on it, and then dimming the lights on the people, to produce the fade on them. The fade-in is made the same way, fading in the lighting on the set first, and then the lighting on the players.”

Toland said that Welles was “one of the most cooperative artists with whom it has been my privilege to work. He let down all bars on originality of photographic effects and angles and I believe the results have fully justified that policy. Photographing Citizen Kane was indeed the most exciting professional adventures of my career.” Ironically, there were no further Welles-Toland collaborations.

Toland’s next assignment, Goldwyn’s The Little Foxes (1941) rivals Kane for dramatic pictorialism, combining the hard-etched pan — focus technique with an almost lacy elegance. “My work began six weeks before we shot the first scene,” Toland said. “There were long conferences with the producer, with William Wyler, the director, with the architect who designed the sets, with the property man and other artisans.

“Discussions with the director involved a complete breakdown of the script, scene by scene, with an eye to the photographic approach, considering the various dramatic effects desired. While this advance discussion pertained to the art ingredient, it was also of economic benefit because it meant the saving of much time and money once actual photography began.

“We built knock-down miniature models of the most important sets and juggled the walls about for the purpose of fixing upon the best angles, the best places to set up the camera. We took into consideration color values, types of wallpaper or background finishes, the color and styles of costumes to be worn by the principals, the furnishings and investiture. We set the photographic key for various sequences — the light ones, dramatically speaking, in a high key of light, the more sombre or moody scenes in a low and more ‘contrasty’ key.

“We determined that Bette Davis, the star, should wear a pure white makeup. This is revolutionary, but it is a potent device in suggesting the kind of character she portrays in the story — a woman waging the eternal conflict with age, trying to cling to her fading beauty. But because of the contrast between her make-up and that of the other principals, we had to discover exactly the balance of light which would illuminate both to advantage. Ascertaining this light balance required extensive make-up tests.

“Other conferences had to do purely with the economic phase. It was discovered that certain sets could be entirely eliminated because their importance to the dramatic whole did not justify their cost. Time being the costliest item in moviemaking, a cameraman must consider it his duty to save all the time he can. If he can set up in 15 minutes instead of a half hour, so much the better.”

His next for Goldwyn, Ball of Fire (1941), was a sudden change of pace, a rambunctious farce directed by Howard Hawks, it made excellent use of contrasting lighting effects in depicting the razzle-dazzle world of a strip-danseuse (Barbara Stanwyck) and the staid, cramped milieu of her unlikely lover, a university researcher (Gary Cooper). Toland later said that in many ways Ball of Fire was the most difficult assignment of his career.

Nearly a year before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, John Ford, who held a USNR commission, organized a volunteer Navy Photographic Unit of cinematographers, film editors and technicians. The first two volunteers were Toland and Joseph August, ASC. Nights and Sundays each cinematographer trained separate groups of six to eight men in the various skills they would need as Navy cameramen.

The unit was called to Washington on active duty within a few days after the Pearl Harbor debacle of December 7, 1941. Lt. Toland was sent to Hawaii to make a full motion picture report of the Japanese attack. The result was a feature-length film, directed and photographed by Toland, called December 7th. Because of the secret nature of much of the film, it could not be released to the public. In 1943 a carefully edited two-reel condensation was released theatrically. It won an Academy Award as Best Documentary Short Subject.

Returning to Washington, Toland worked in the training program and co-designed a special combat camera. Later, he was sent to Brazil, where he produced Navy and OSS documentaries.

He returned to the Goldwyn Studio in 1945 to make a Danny Kaye musical comedy in Technicolor, The Kid From Brooklyn. Although color photography had improved tremendously since his work with the two-color process of a decade earlier, Toland remained loyal to black-and-white as a dramatic medium.

“Color will continue to be improved but will never be 100% successful,” he wrote. “Nor will it ever fully replace black-and-white film because of the inflexibility of light in color photography and the consequent sacrifice of dramatic contrasts. Anything done in the gay, high-light which color photography necessitates for its existence (such as musical comedies) will continue to be suitable as a subject for color film. But the low-key, more dramatic use of light seems to me automatically to rule color out in pictures of another type.

“Paradoxically enough, realism suffers in the color medium. The sky, as reproduced, is many shades deeper than its natural blue. The faces of the characters are usually a straw shade. Three prime colors are utilized but not enough shades are possible with those three. More basic colors would involve too complex a problem to be economically practicable. In the black-and-white picture, color is automatically supplied by the imagination of the spectator and the imagination is infallible, always supplying exactly the right shade. That is something physical science will continue to find tough competition.”

However, The Kid From Brooklyn had its compensations. One of the gorgeous “Goldwyn Girls” in the film, Virginia Thorpe, became Mrs. Toland. The marriage took place at Nogales on December 9, 1945.

On loan to Walt Disney, Toland photographed one of the most beautiful of all Technicolor films, Song of the South (1946). The live-action photography was combined with animated cartoons of Joel Chandler Karris’ Uncle Remus characters to brilliant effect.

He returned to his black-and-white pan-focus technique for Goldwyn’s The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), his most celebrated picture since Kane. Toland said he wanted the photography to appear “honest” with no striving for unusual effects and “chi-chi.” This story of returning veterans won Goldwyn the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award, brought Oscars to director William Wyler, scenarist Robert E. Sherwood, film editor Daniel Mandell, composer Hugo Friedhofer, actors Fredric March and Harold Russell (Russell also received a second special award), and won the Best picture award. Toland did not receive a nomination.

The Bishop’s Wife (1947), a comedy-fantasy with Cary Grant, Loretta Young and David Niven, is a slick black-and-white production with beautiful snow scenes. A Song Is Born (1947), Howard Hawks’ remake of Ball of Fire as a Danny Kaye special, again proved that Toland handled color well even though he didn’t entirely approve. Included are the low-key effects he earlier had said were not practical for color — expertly done, needless to say. Enchantment (1948) is a romantic story photographed in a subtle, sometimes impressionistic black-and-white.

In April of 1948, Toland went to London for six weeks to shoot background plates for a project he never completed, Take Three Tenses, from a story by Rumer Godden. Late in September he went on location in the mountains near Sonora, California, for preliminary work on Goldwyn’s Roseanna McCoy. He returned to his West Hollywood home on a Saturday complaining of feeling tired. He rested at home for two days, then died suddenly on September 28 of a coronary attack. He was 44.

Toland’s contract with Goldwyn, signed in 1926, was still in force at the time of his death. It had afforded him greater freedom over a longer period of time than has been given any other cinematographer. Behind his melancholy countenance surged a great joy in his work.

“Of all the people who make up a movie production unit,” Toland once said, “the cameraman is the only one who can call himself a free soul.”

This profile was originally published in AC Nov. 1982. Some images are additional or alternate.

AC Archive subscribers can access this entire issue, as well as more than 1,200 others. Subscribe here.