Realism for Citizen Kane

The cinematographer details his visual approach, facilitated not only by technical advances, but his open collaboration with producer-director-star and co-scenarist Orson Welles.

Originally published in AC Feb., 1941

Republished in AC Aug., 1991 for the film’s 50th Anniversary

During recent years a great deal has been said and written about the new technical and artistic possibilities offered by such developments as coated lenses, super-fast films and the use of lower-proportioned and partially ceiled sets. Some cinematographers have had, as I did in one or two productions filmed during the past year, opportunities to make a few cautious, tentative experiments with utilizing these technical innovations to produce improved photo-dramatic results. Those of us who have, I am sure, have felt, as I did, that they were on the track of something really significant, and wished that instead of using them conservatively for a scene here or a sequence there, they could experience free-handedly with them throughout an entire production.

In the course of my last assignment, the photography of Orson Welles' Citizen Kane, the opportunity for such a large-scale experiment came to me. In fact, it was forced upon me, for in order to bring the picture to the screen as both producer-director Welles and I saw it, we were forced to make radical departures from conventional practice. In doing so, I believe we have made some interesting contributions to cinematographic methods.

Citizen Kane is by no means a conventional, run-of-the-mill movie. Its keynote is realism. As we worked together over the script and the final, pre-production planning, both Welles and I felt this, and felt that if it was possible, the picture should be brought to the screen in such a way that the audience would feel it was looking at reality, rather than merely at a movie.

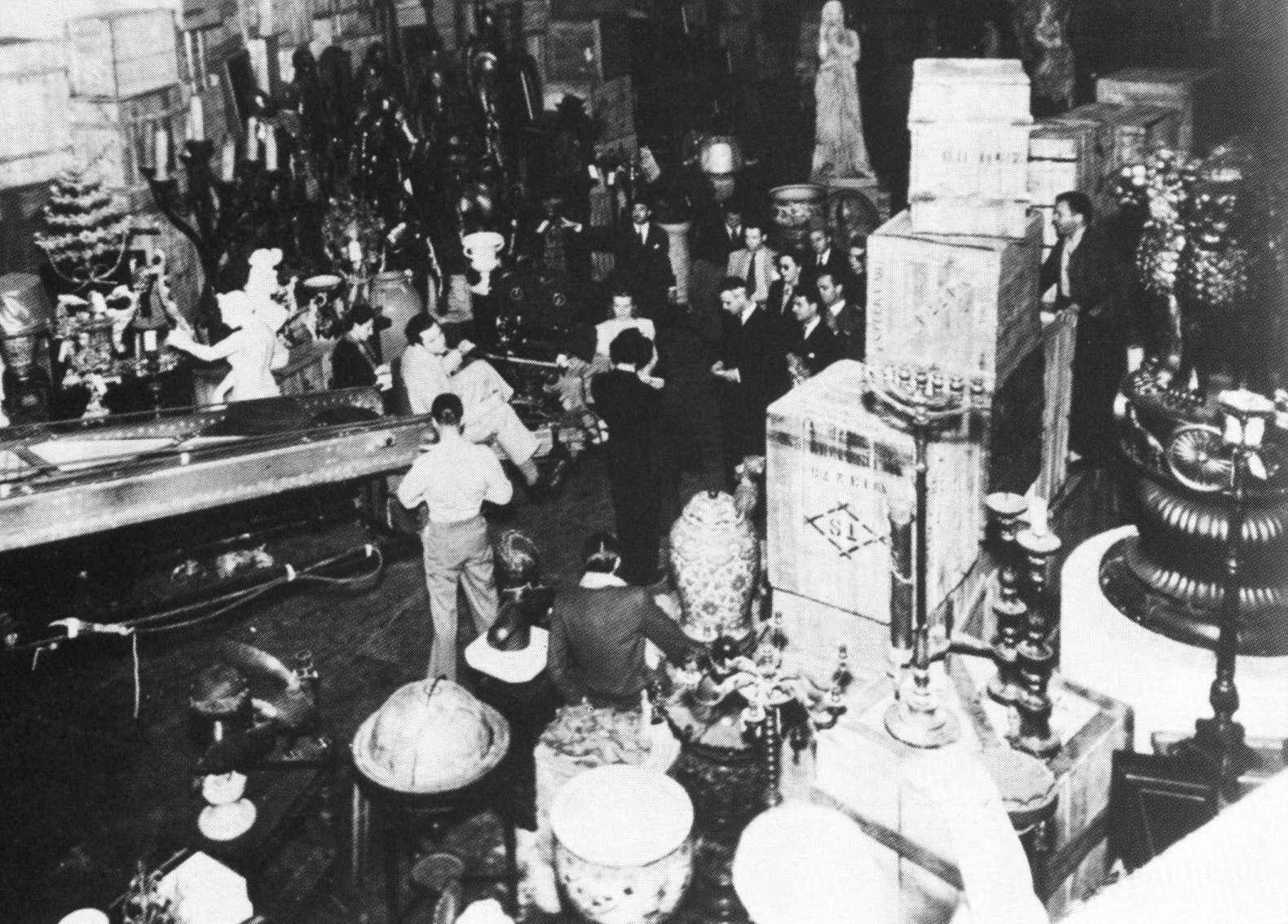

Closely interrelated with this concept were two perplexing cine-technical problems. In the first place, the settings for this production were designed to play a definite role in the picture — one as vital as any player's characterization. They were more than mere backgrounds: they helped trace the rise and fall of the central character.

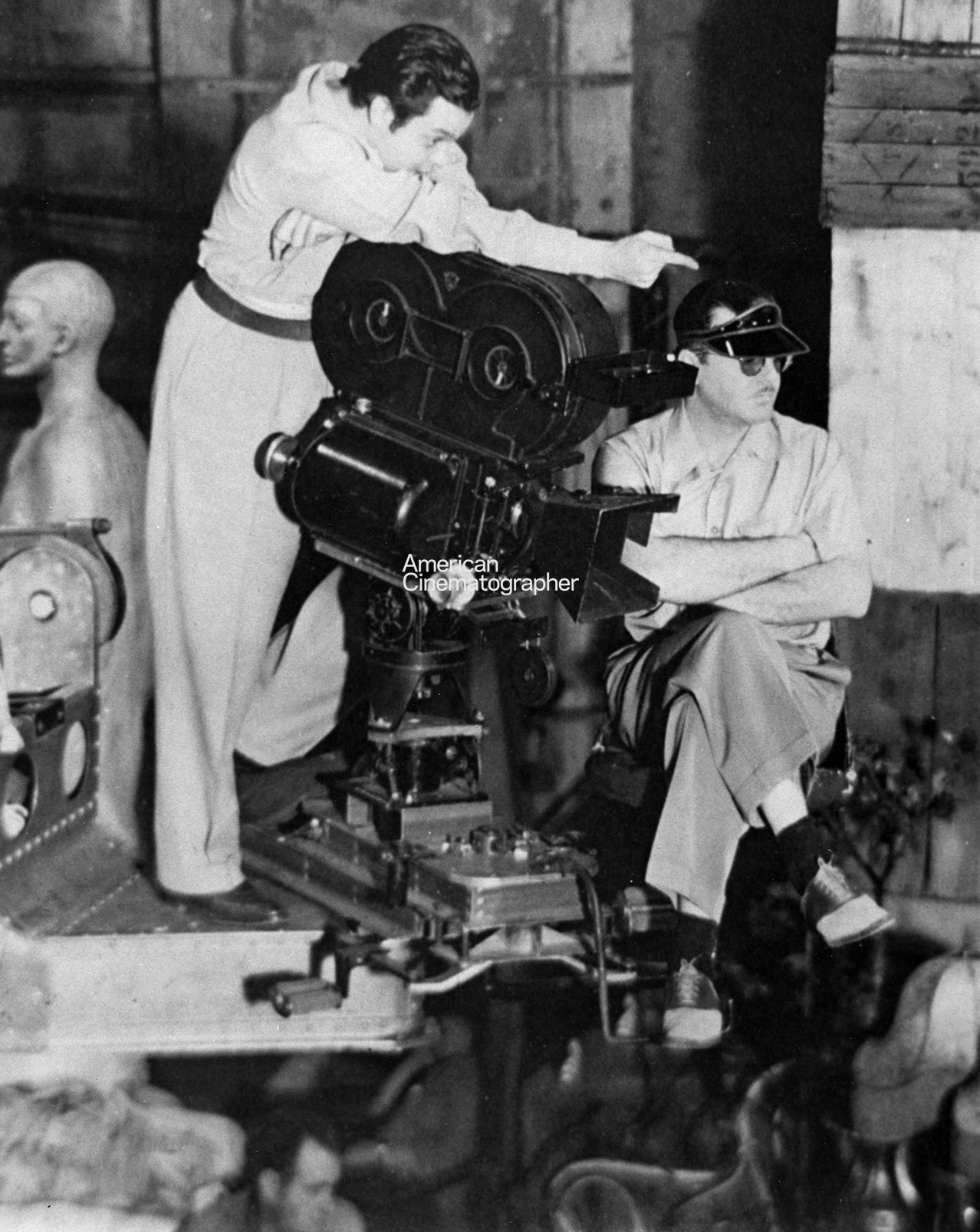

Secondly — but by no means of secondary importance — was Welles' concept of the visual flow of the picture. He instinctively grasped a point which many other far more experienced directors and producers never comprehend: that the scenes and sequences should flow together so smoothly that the audience should not be conscious of the mechanics of picture-making. And in spite of the fact that his previous experience had been in directing for the stage and for radio, he had a full realization of the great power of the camera in conveying dramatic ideas without recourse to words.

“I would like to pay high tribute to those who were associated with the making of Citizen Kane. Producer-director Orson Welles, of course, heads the list; he is not only a very brilliant young man, but also one of the most delightfully understanding and cooperative producers and directors with whom I have ever worked.”

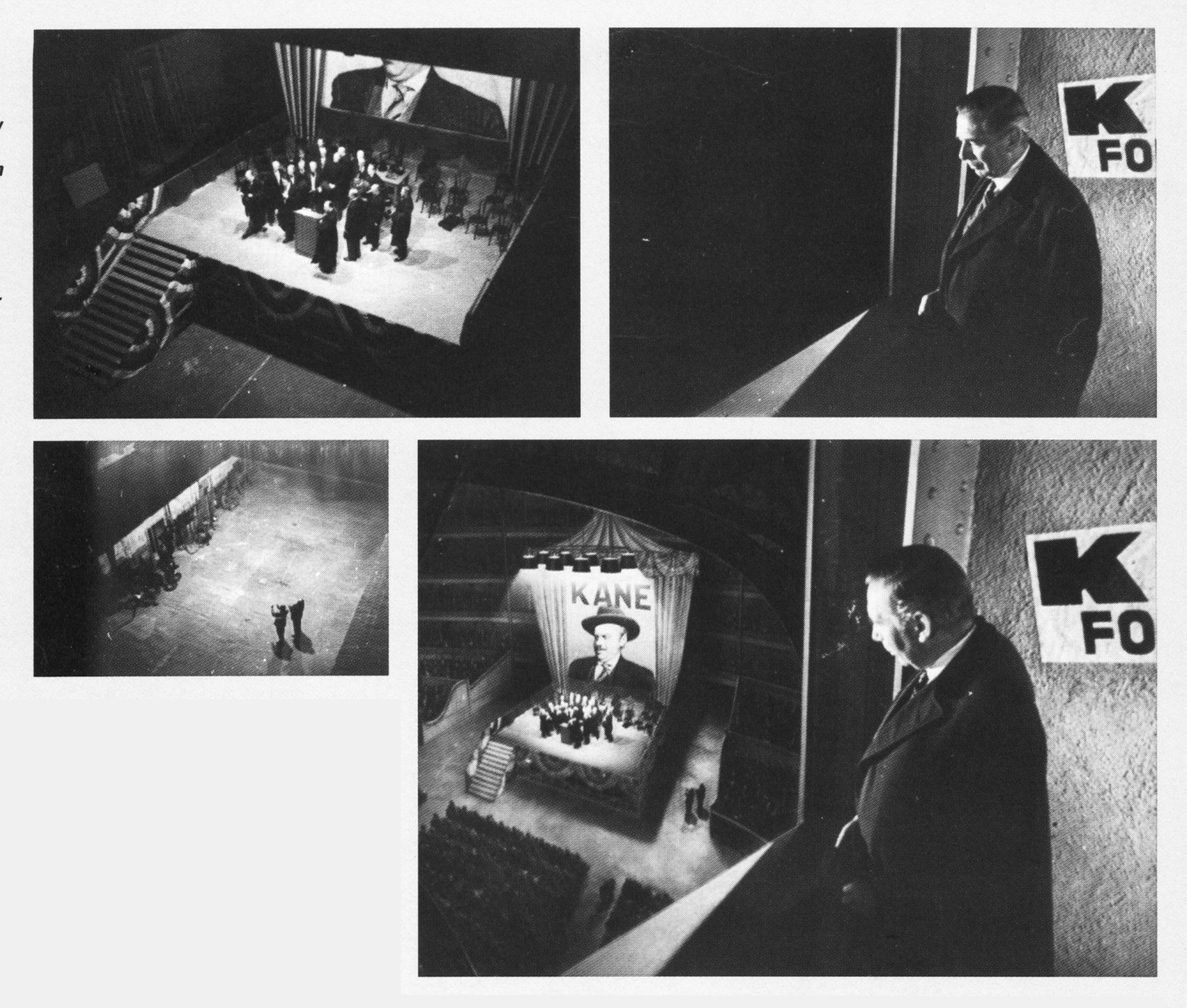

Therefore, from the moment the production began to take shape in script form, everything was planned with reference to what the camera could bring to the eyes of the audience. Direct cuts, we felt, were something that should be avoided wherever possible. Instead, we tried to plan action so that the camera could pan or dolly from one angle to another whenever this type of treatment was desirable. In other scenes, we pre-planned our angles and compositions so that action which ordinarily would be shown in direct cuts would be shown in a single, longer scene — often one in which important action might take place simultaneously in widely separated points in extreme foreground and background.

These unconventional setups, it can readily be seen, impose unsurmountable difficulties in the path of strictly conventional methods of camerawork. To put things with brutal frankness, they simply cannot be done by conventional means. But they were a basic part of Citizen Kane and they had to be done!

The first step was in designing sets which would, in themselves strike the desired note of reality. In almost any real-life room, we are always to some degree conscious of the ceiling. In most movies, on the other hand, we see the ceiling only in extreme long-shots — and then it is usually painted in as a matte shot. In the closer angles, the camera seldom shows the ceiling, or even anything suggesting it. On the contrary, conventional interior lighting effects, since the light is projected from spotlighting units perched high on the lamp rails paralleling the sets, come from angles which would be definitely impossible in an actual, ceiled room.

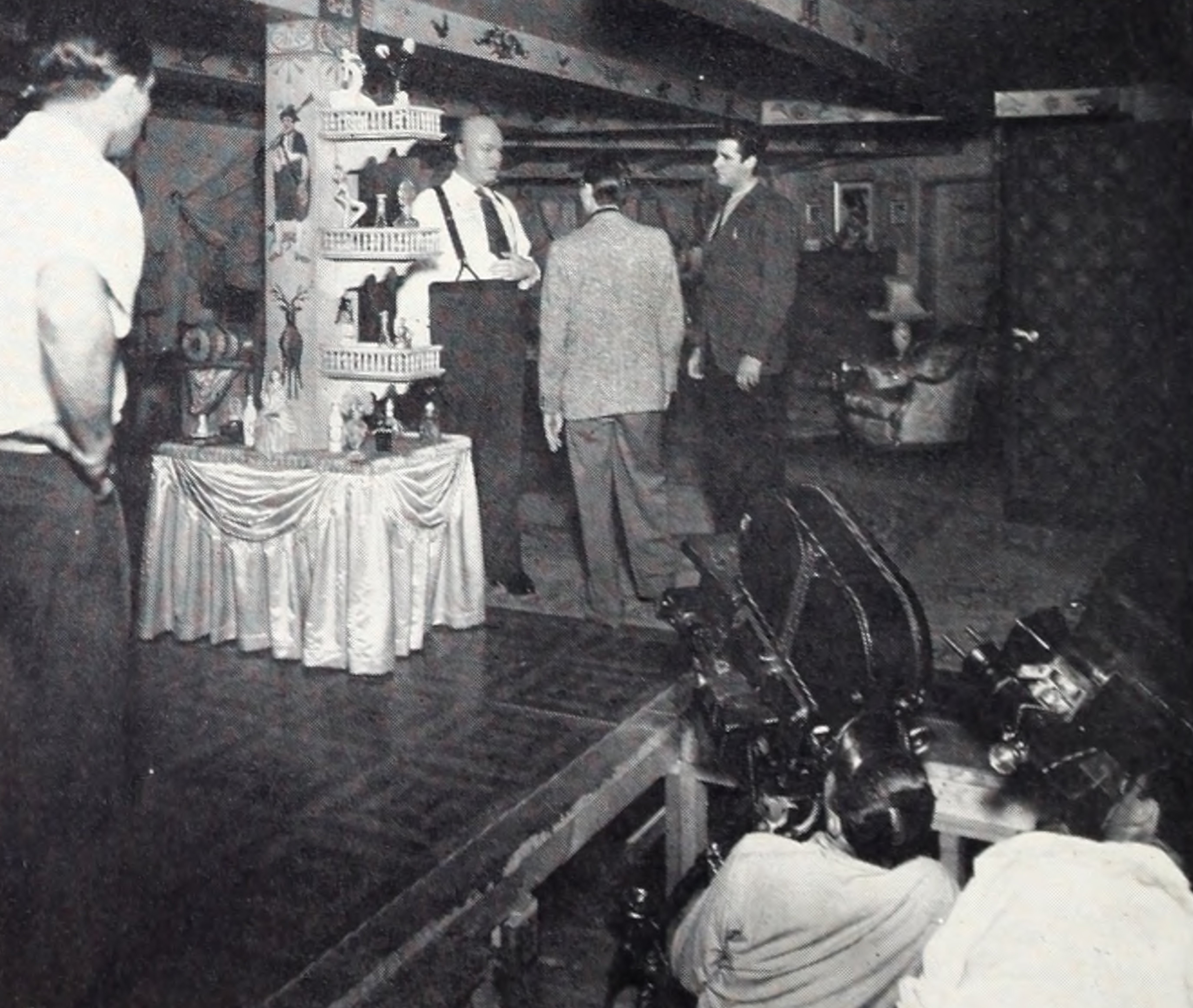

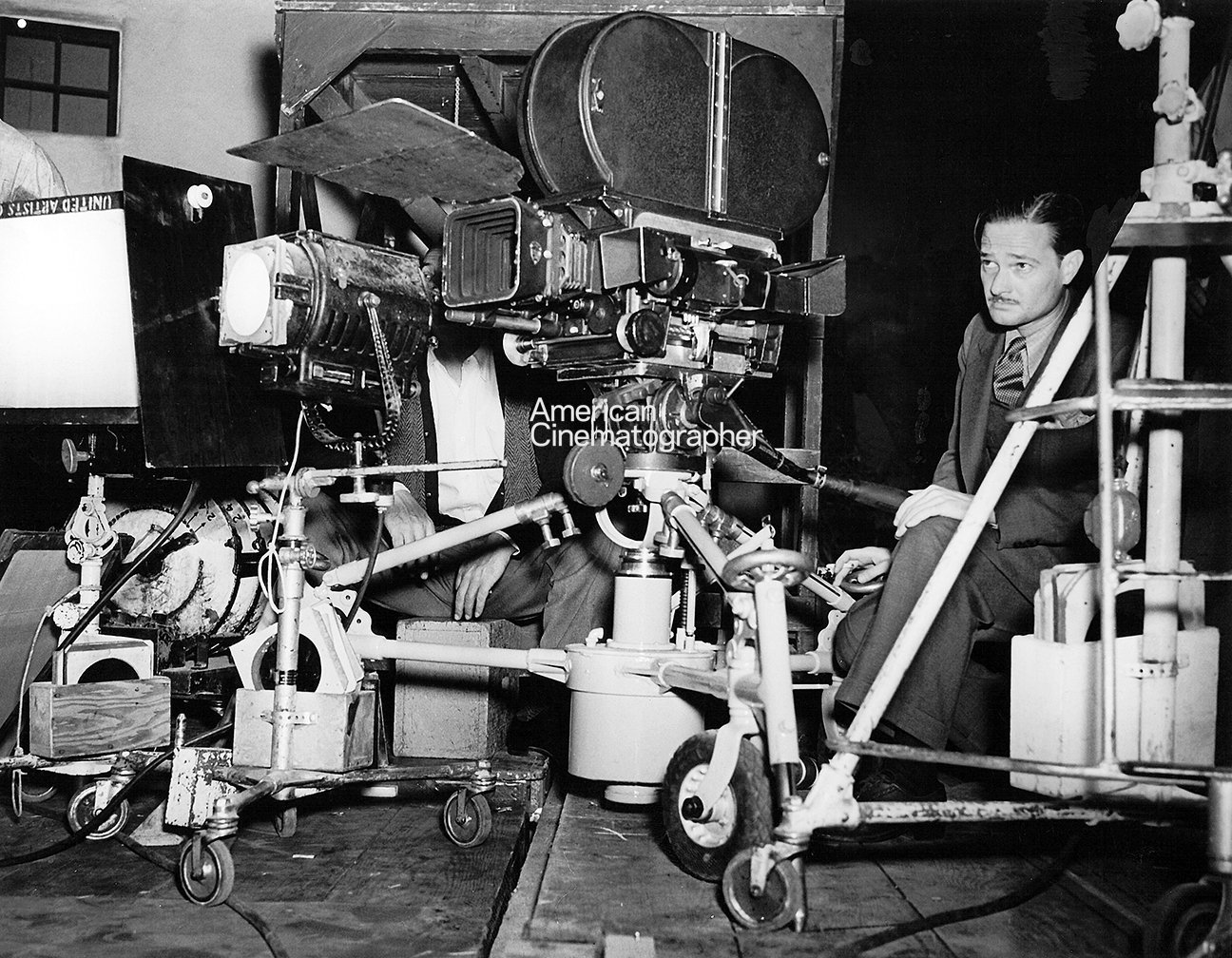

Therefore, the majority of our sets for Citizen Kane had actual ceilings. They were low ceilings — in many instances even lower than they would be in a real room of similar style. Furthermore, many of our camera angles were planned for unusually low camera setups, so that we could shoot upward and take advantage of the more realistic effects of those ceilings. Several sets were even built on parallels so that we could take up any desired section of the flooring and place the lens actually at floor level.

This, as may be imagined, immediately created a very interesting problem in lighting. Since the sets were ceilinged, not one of the 110 sets were paralleled for overhead lighting. With the exception of a few occasional shots for which we could remove a small section of ceiling to permit a "Junior" or similar spotlight overhead for really necessary backlighting, everything in the picture was to be lighted from the floor.

With deep sets, this necessitated the use of light which would have great penetrating power. This was found in the twin-arc broadsides developed for use in Technicolor. These lamps formed the backbone of our lighting, supplemented of course with "Juniors," "Seniors," and 170-amp arc spots as might be necessary.

In passing, it may be mentioned that this technique of using completely ceilinged sets so extensively gave us another advantage: it eliminated that perpetual bane of the cinematographer — microphone shadows. The ceilings were made of muslin, so the engineers found no difficulty at all in placing their mikes just above this acoustically porous roof. In this position, they were always completely out of camera range, and as there was no overhead lighting, they couldn't cast any shadows. Yet the ceilings were so low that the mike was almost always in a very favorable position for sound pickup. I must admit, however, that working this way for 18 or 19 weeks tends to spoil one for working under more conventional conditions, where one must always be on the lookout lest the mike or its shadow get into the picture!

“While the human eye is not literally a universal focal optical instrument, its depth of field is so great and its focus changes so completely automatic that for all practical purposes, it is a perfect universal-focus lens.”

The next problem was to obtain the definition and depth necessary to Welles' conception of the picture. While the human eye is not literally a universal focal optical instrument, its depth of field is so great and its focus changes so completely automatic that for all practical purposes, it is a perfect universal-focus lens.

In a motion picture, on the other hand, especially in interior scenes filmed at the large apertures commonly employed, there are inevitable limitations. Even with the 24mm lenses used for extreme wide-angle effects, the depth of field—especially at the focal settings most frequently used in studio work (on the average picture, between 8 and 10 feet for the great majority of shots)—is very small. Of course, audiences have become accustomed to seeing things this way on the screen, with a single point of perfect focus, and everything falling off with greater or less rapidity in front of and behind this particular point. But it is a little note of conventionalized artificiality which bespeaks the mechanics and limitations of photography. And we wished to eliminate these suggestions wherever possible.

Now it is well known that the use of lenses of short focal length tends in itself to increase the depth of field. So, too, does stopping down the lens.

Since the introduction of today's high-speed emulsions, some photographers and some studios have made it a practice to take advantage of the film's speed by stopping their lenses down to apertures as low as f:3.5 or thereabouts when filming interiors. In some instances this is done only occasionally, when for some reason added depth may be desired for a scene or sequence; in others, it is a fixed practice.

To solve our problem, we decided to carry this idea a step further. If using a high-speed film like PlusX and stopping down to f:3.5 gave a desirable increase in definition, wouldn't it — for our purpose, at least — be a still better idea to employ a super-speed emulsion like Super-XX, and to stop down even further? [Note: the 1940 Super XX had a Weston meter rating of 64. This would approximate the ASA rating.]

Preliminary experiments proved that it was. However, merely stopping down to the extent which would compensate for the higher sensitivity of Super XX was still not enough, though we were clearly on the right track.

The next step inevitably was to stop down to whatever point might give us the desired depth of field in any given scene, compensating for the decreased exposure values by increasing the illumination level.

This technique, especially on deep, roofed-in sets where no overhead lighting could be used, naturally created another lighting problem. Fortunately, two other factors helped to make this less troublesome than might have been expected.

First, we were using, as I have been for some time, lenses treated with the Vard "Opticote" non-glare coating. In view of the considerable discussion that has arisen since the introduction of these treating methods, I may mention that so far I have found this treatment not only beneficial, but durable. Depending upon the design of the lens to which it is applied, it gives an increase in speed ranging between half a stop and a stop, while at the same time giving a very marked increase in definition, due to the elimination of flare and internal reflections.

Secondly, due to the nature of our sets, and the lighting problems incident to our use of ceilinged sets, we were, even before we changed from Plux-X to Super-XX, making considerable use of arc broadsides. In addition to the greater penetrating power of arc light as compared to incandescent, this gave us a further advantage, for the arc is unexcelled in concentrating the greatest illuminating power into a comparatively small unit.

The use of these lamps made it possible to use considerably smaller lens apertures than would otherwise have been the case, while still keeping to satisfactorily low illumination levels, and using surprisingly few lighting units. In many scenes, including even some in the big sets representing Xanadu, Kane's exaggeratedly palatial Florida estate, the entire lighting was accomplished using a total of only five or six units, including the arc broads and incandescent spotlights of all sizes.

It was therefore possible to work at apertures infinitely smaller than anything that has been used for conventional interior cinematography in many years. While in conventional practice, even with coated lenses, most normal interior scenes are filmed at maximum aperture or close to it — say within the range between f:2.3 and f:2.8, with an occasional drop to an aperture of f:3.5 sufficiently out of the ordinary to cause comment — we photographed nearly all of our interior scenes at apertures not greater than f:8 — and often smaller. So the scenes were filmed at f:l 1, and one even at f:16!

How completely this solved our depth of field problem may easily be imagined. Even the standard 50mm and 47mm objectives conventionally used have tremendous depth of field when stopped down to such apertures. Wide-angle lenses such as the 35mm, 28mm and 24mm objectives, when stopped down to f:11 or f:16, become for all intents and purposes universal-focus lenses.

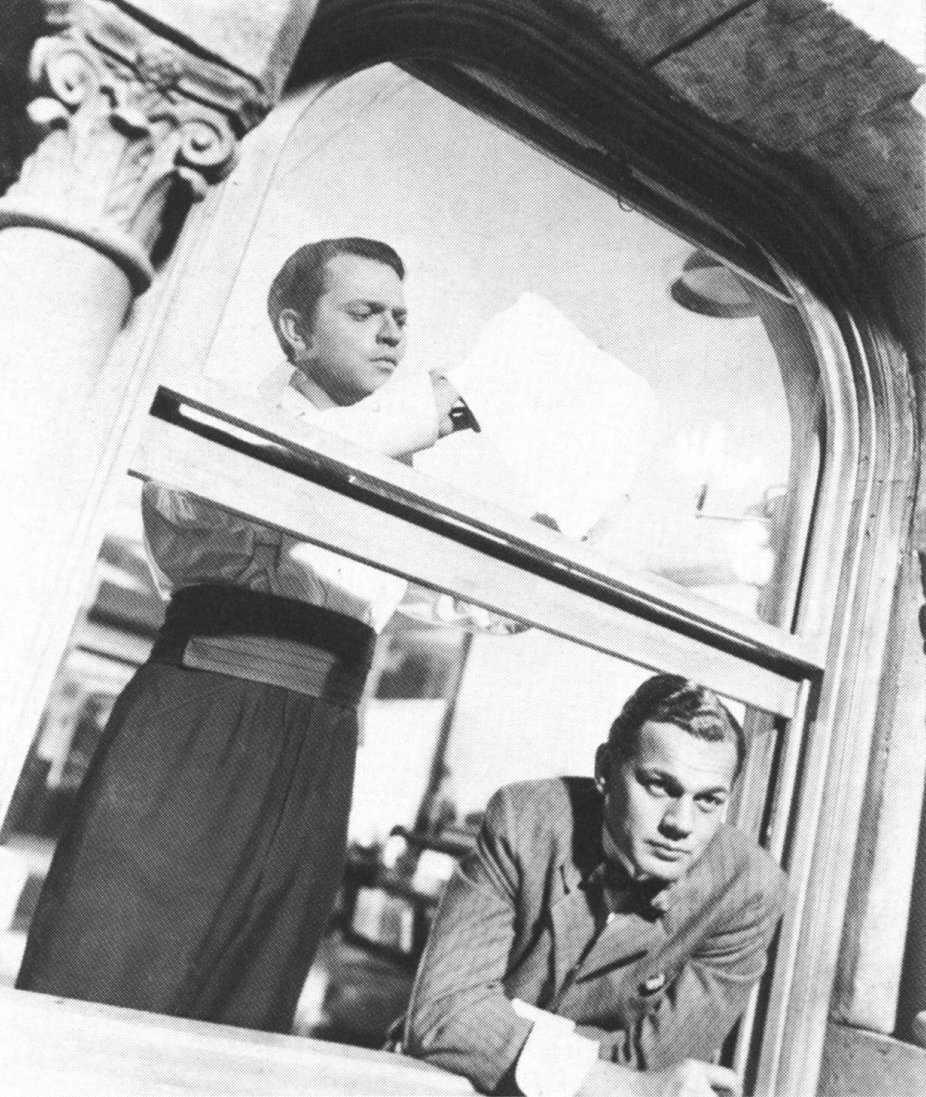

But we needed every bit of depth we could possibly obtain. Some of the larger sets extended the full length of two stages at the RKO-Pathe Studio and necessitated holding an acceptably sharp focus over a depth of nearly 200 feet. In other shots, the composition might include two people talking in the immediate foreground — say two or three feet from the lens — and framing between them equally important action taking place in the background of the set, 30 or 40 feet away. Yet both the people in the immediate foreground and the action in the distance had to be kept sharp!

In still other shots, Welles' technique of visual simplification might combine what would conventionally be made as two separate shots — a close-up and an insert — in a single, non-dollying shot. One such shot, for instance, was a big-head close-up of a player reading the inscription on a loving cup. Ordinarily, such a scene would be shown by intercutting the close-up of the man reading the inscription with an insert of the inscription itself, thereafter cutting back again to the close-up. As we shot it, the whole thing was compressed into a single composition. The man's head filled one side of the frame; the loving cup the other. In this instance, the head was less than 16 inches from the camera, while the cup was necessarily at arm's length — a distance of several feet. Yet we were able to keep the man's face fully defined, while at the same time the loving cup was in such sharp focus that the audience was able to read the inscription from it. Also, beyond this foreground were a group of men from 12 to 18 feet focal distance. These men were equally sharp.

This unorthodox technique, as might be expected, brought with it a completely new set of photographic and lighting problems. Solving them taught us a lot. For example, there is the matter of setting focus on scenes like these, where it is necessary to spread the depth of field over an incredibly great area. Any experienced cinematographer or still photographer will automatically reply, "That's easy — just split your focus between the nearest and farthest points you want to keep in focus!" Yes — that's the answer — but where should you focus your lens in order to do this?

This is something only practical experience can answer consistently, for while the depth of field of all lenses falls off more sharply in front of the point of focus than behind it, this effect varies not only according to the focal length of the lens used, but according to the degree to which it is stopped down and the point upon which it is focused. Gaining this experience, one certainly learns surprising things about the behavior of lenses.

“Thanks to the spirit of understanding and cooperation which prevailed, we emerged with what I think will prove a notable picture and, I hope, the starting point of some new ideas in both the technique and the art of cinematography.”

If it is set to focus on a point 4 feet 6 inches in front of the camera, everything from 18 inches to infinity will be in acceptably sharp focus. There are also some lenses which, as they are stopped down, suddenly reveal totally unexpected optical characteristics at certain settings, and quite as inexplicably lose them as they are stopped down further. I have known of instances in which lenses were excellent until they were closed down to, say, f:6.3, but became distinctly inferior at apertures below this point — only to recover their quality again as the diaphragm passed the f:ll or f:16 mark.

Lighting for this combination of ultra-fast film, coated lenses and radically reduced apertures offers its own new problems. One has to learn a completely new system of lighting balance. The fast film tends to flatten contrasts, but the coated lenses and the reduced apertures both tend to increase contrast. As a result, one must light scenes made in this manner with much less contrast than would be customary under more normal circumstances.

Again, the precise degree of change depends upon the stop used; but in general, the shadows must be "opened up" with a more general use of filler light, the highlights must be watched, and when optical diffusion is used, diffusers such as the Scheibes, which tend to soften contrasts, are generally preferable. Obviously, too, when you are dealing with film of the extreme sensitivity of Super-XX, you will find that even at reduced apertures, extremely delicate graduations of lighting-contrast pick up, registering far more strongly on the film than they do to even the trained eye. Yet, strangely enough, once a cinematographer has accustomed himself to this type of lighting, it becomes in many ways easier than more conventional lighting, for it is simpler, less artificial, and employs fewer light sources.

A further innovation in this picture will be seen in the transitions, many of which are lap-dissolves in which the background dissolves from one scene to another a short but measurable interval before the players in the foreground dissolve. This is done quite simply, by having the lighting on set and people rigged through separate dimmers. Then all that is necessary is to commence the dissolve by dimming the background lights, effectually fading out on it, and then dimming the lights on the people, to produce the fade on them. The fade-in is made the same way, fading in the lighting on the set first, and then the lighting on the players.

In closing, I would like to pay high tribute to those who were associated with the making of Citizen Kane. Producer-director Orson Welles, of course, heads the list; he is not only a very brilliant young man, but also one of the most delightfully understanding and cooperative producers and directors with whom I have ever worked. Art director Perry Ferguson is another whose ability helped make Citizen Kane an unusual production. His camera-wise designing of the settings not only made it possible to obtain many of the effects Welles and I sought, but also made possible the truly remarkable achievement of building the production's 110 sets, large and small, for a total expenditure of about $60,000 — sets which look on the screen like a much larger expenditure. RKO special effects expert Vernon Walker, ASC, and his staff handled their part of the production — by no means an inconsiderable assignment — with ability and fine understanding. Finally, the operative crew who have been with me for so many years — operative cinematographer Bert Shipham and assistant cameraman Eddie Garvin — played their accustomed parts in helping me to put Orson Welles' initial production on the screen. Experimenting as we were with new ideas and new methods, none of them had an easy time. But thanks to the spirit of understanding and cooperation which prevailed, we emerged with what I think will prove a notable picture and, I hope, the starting point of some new ideas in both the technique and the art of cinematography.

Toland earned an Academy Award nomination for his outstanding work in the picture, which, in 2019 was included on the ASC’s list of 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.

You’ll find our complete retrospective on Toland's career here.

Access the every issue of AC and every story from more than the last 100 years with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.