A Silent Giant: 1923’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame

Universal’s largest-scale silent film is in large part of what made Lon Chaney a legend, and paved the way for the rest of their enduring legacy of gothic horror from the golden age of film.

The early 1920s were years of great artistic and technical growth for motion pictures. So many outstanding films were made during that time that it is virtually impossible to pick a single favorite.

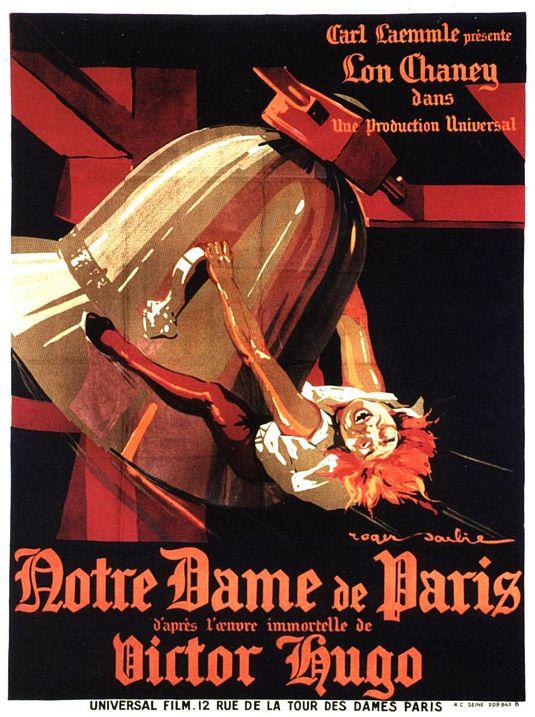

Certainly, a leading contender is 1923’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame, produced at Universal City under the benign dictatorship of president Carl Laemmle and his youthful production executive, Irving G. Thalberg. It has spectacle in the best sense of the word, fine performances, cinematography which set new standards in several respects, steady direction which kept all the sprawling elements of the picture under control, magnificent settings, and faithfulness to the spirit of a literary classic. It was one of the most expensive silent films, costing more than $1,250,000.

Universal at the time specialized in the making of inexpensive program pictures which were sold in packages to exhibitors. These were graded by Laemmle as to importance and quality, the top line product being designated as Universal Jewels, then Junior Jewels, Specials, etc. There was an occasional Super Jewel, meaning a picture so far above the ordinary as to demand special handling, higher rentals and longer playdates. Of this mere handful (which includes Foolish Wives, Merry-Go-Round, Phantom of the Opera and Uncle Tom’s Cabin), Laemmle’s favorite and the company’s biggest was Hunchback.

In adapting Victor Hugo’s 1831 novel, Notre Dame de Paris, Perley Poore Sheehan and Edward T. Lowe made many changes, some in the interest of paring the story down to a practical length for the screen, partly to relieve some of the gloom which permeates the novel but would hardly be acceptable to theater audiences of the time, and partly to eliminate Hugo’s criticisms of the church.

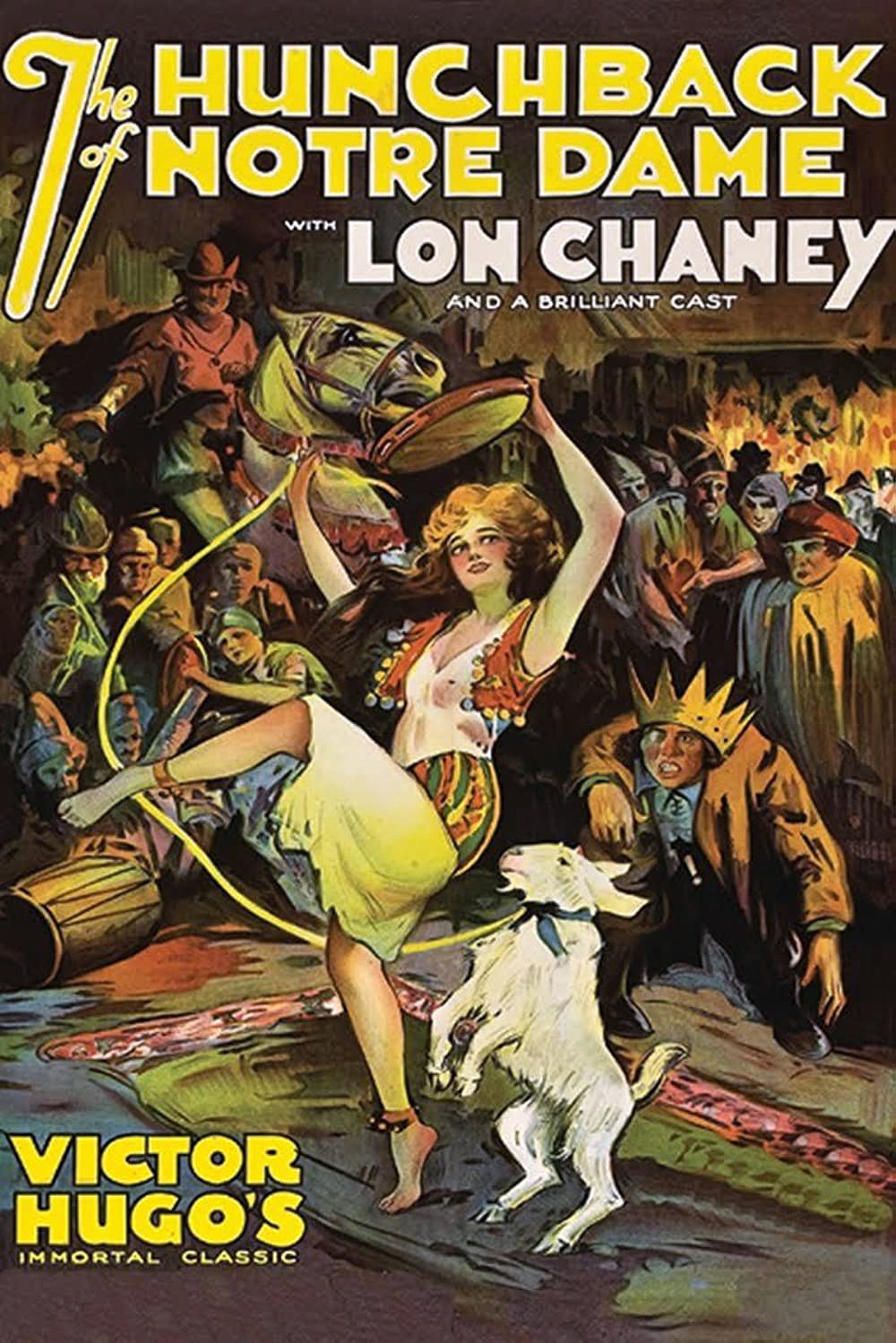

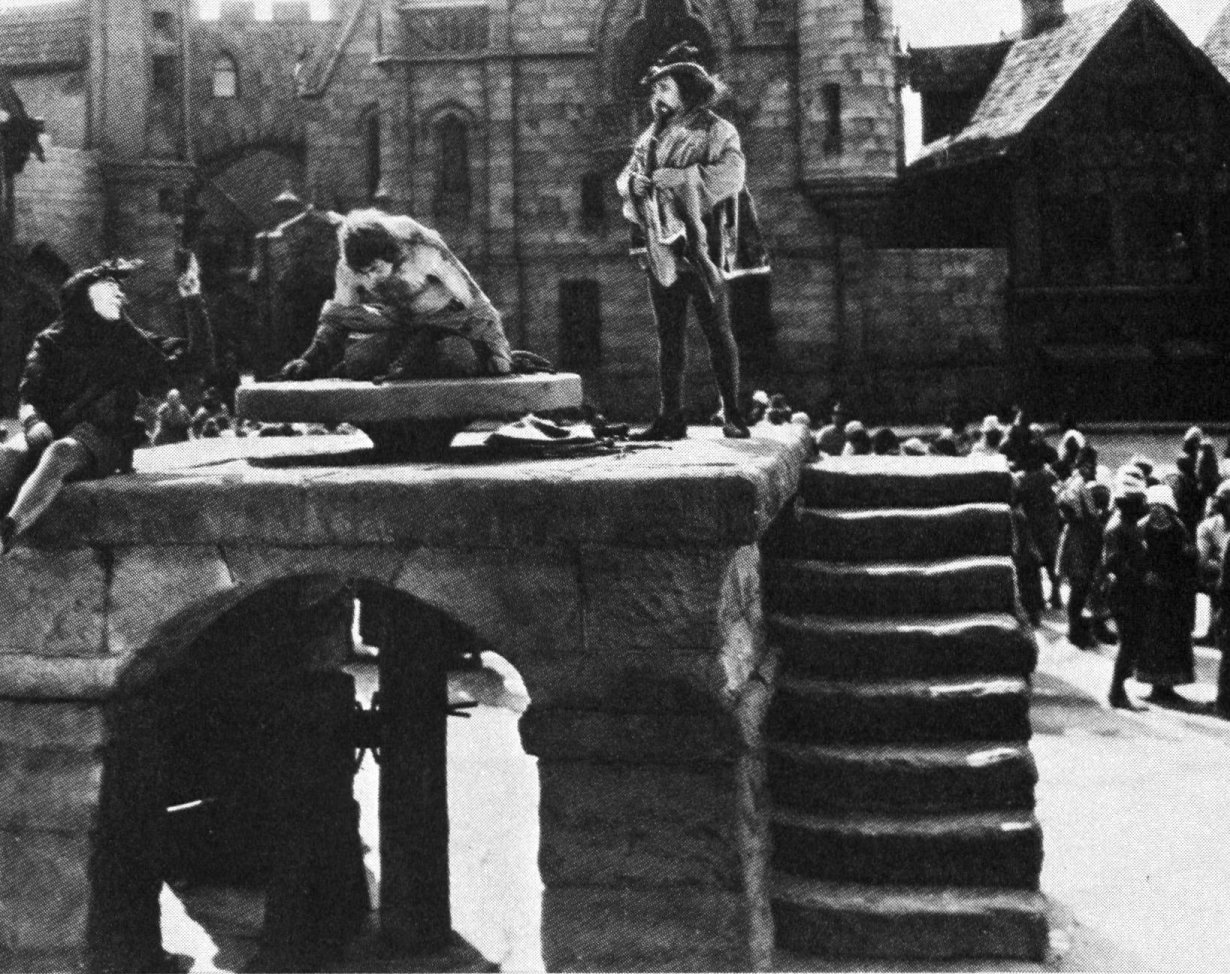

The film centers on Quasimodo, the deformed bell-ringer of the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris, in 1482. He is ordered by Jehan, evil brother of the archdeacon, to kidnap Esmeralda, a beautiful Gypsy dancing girl and ward of the king of the underworld, Clopin. She is rescued by the dashing Captain Phoebus and Quasimodo is sentenced to be lashed in the public square.

Esmeralda, taking pity, brings him water and stirs in him a hopeless love. Jehan jealously stabs Phoebus as he embraces Esmeralda. The girl is blamed and sentenced to be hanged in front of Notre Dame. Quasimodo climbs down from the cathedral tower and carries Esmeralda into the sanctuary of the church. Clopin leads his army of beggars, thieves and murderers from their quarter, known as the Court of Miracles, to storm Notre Dame. Quasimodo, thinking they are trying to return the girl to the gallows, hurls building blocks and beams down on them. He finally routs the attack by pouring molten lead onto the rabble. The King’s guards disperse the mob as Clopin dies. Jehan now tries to attack Esmeralda in the tower. In rescuing her, Quasimodo is fatally stabbed before throwing Jehan from the tower. Esmeralda learns that Phoebus is alive and that she has been exonerated. As she leaves, Quasimodo tolls the church bells, then dies.

Laemmle and Thalberg agreed that only Lon Chaney could portray Quasimodo. Even while early research was being done by Sheehan in Paris and the physical aspects of the production were being planned, Thalberg was trying to sign the reclusive actor, who was being difficult because of a grudge against the studio. An agreement was reached late in 1922.

A number of important directors had been considered. Chaney was instrumental in bringing in Wallace Worsley, who had directed him in the Goldwyn production The Penalty. A veteran actor and producer of the New York stage, Worsley became a film director in 1917 and had worked for most of the major studios. Hunchback was both his finest work and his last large-scale directorial effort. After it was completed, he devoted most of his efforts to the making of travel pictures. He died in 1944.

Worsley was aware of Chaney’s directorial ability and allowed him to direct some of his own scenes. In staging the gigantic crowd scenes, in which as many as 2,500 extras appeared, Worsley utilized — for the first time in motion picture production — a public address system. This was the new Western Electric Public Address Apparatus, which made it possible for the director to give orders to actors and crew members in all parts of the vast set. An ex-army officer, George M. Stallings, and ten assistant directors, headed by Jimmy Dugan and Jack Sullivan, helped to control the mass of players. One of the assistant-assistants was a Laemmle relative from France, William Wyler.

Many modern critics have pondered Universal’s choice of a comparatively little-known director for a picture that competed (successfully) with the outstanding historical epics of the silent screen. However, a study of the film reveals that Hunchback has all the virtues and few of the faults of pictures produced by the better-known makers of this type of film: the crowds are handled with great skill, the individual performances are first rate (yet even Chaney is unable to reduce Hugo’s concept to a star vehicle), the photographic technique is superior to any picture of its kind of the period, and there is a welcome absence of the dramatic excesses that marred Cecil B. DeMille’s films or the exaggerated sentimentality that Griffith so often fell prey to. And if this be heresy...

Elmer E. Sheeley was in charge of set design, with Sidney Ullman as his first assistant. Archie Hall was the technical director in charge of set construction. Stephen Goosson — who designed Shangri La for Lost Horizon a dozen or so years later — worked with Ullman and several other artists in a special drafting room over the main stage. Their drawings, which combined the factual with the fanciful, were based upon old prints of the architecture of the period, including a collection of sketches made by Victor Hugo. These designs were translated into plans which were blueprinted and delivered to Hall.

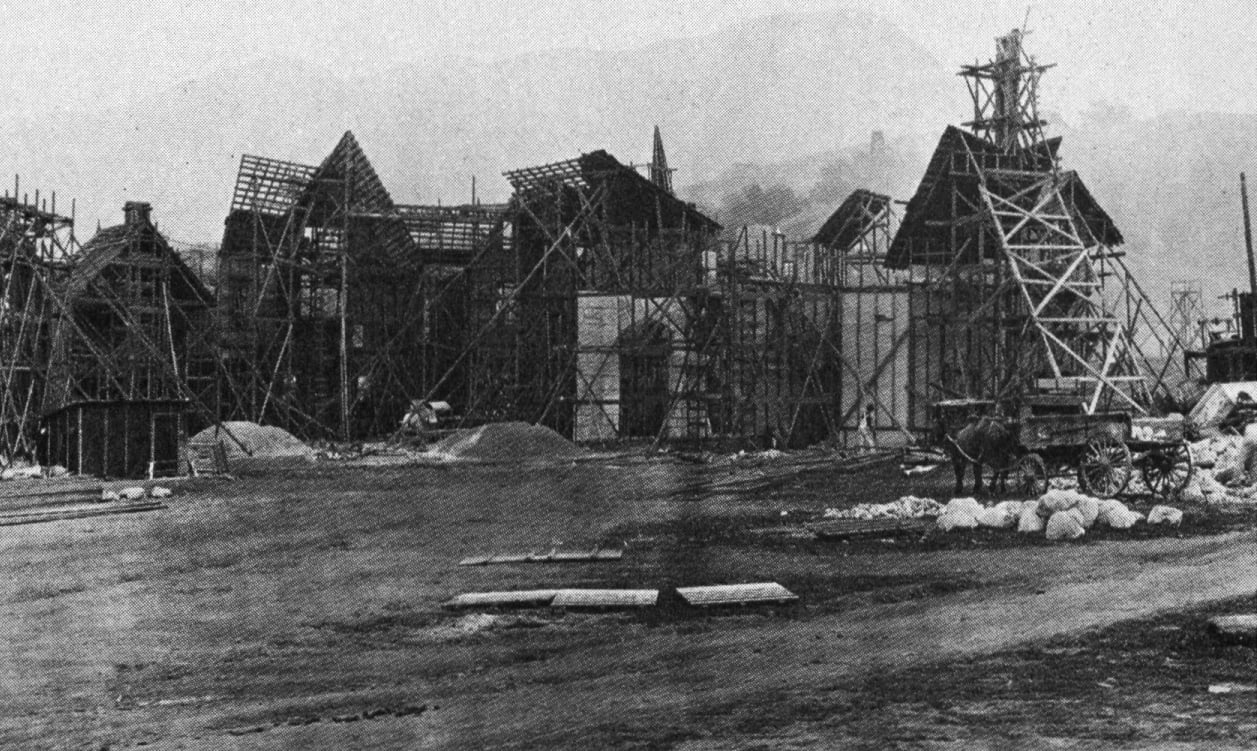

Meantime, 60 workmen hauled in cobblestones from a river 20 miles away and laid them in cement beds — the streets of old Paris. Flagstones were molded in cement and laid in a long row in front of a string stretched between two poles to indicate the front line of the cathedral site. To lay out the cathedral place it was necessary to cut off one flank of a mountain and fill in a large swale.

Carl Laemmle told Hall that the sets should be built as solidly as the real thing, just as had been done previously with the Monte Carlo and Vienna sets for Erich von Stroheim’s extravaganzas Foolish Wives and Merry-Go-Round. It was his theory that the sets could be used in many other productions, and he was right. They remained in use for four decades, until the cathedral and most of the other buildings were destroyed in a disastrous fire.

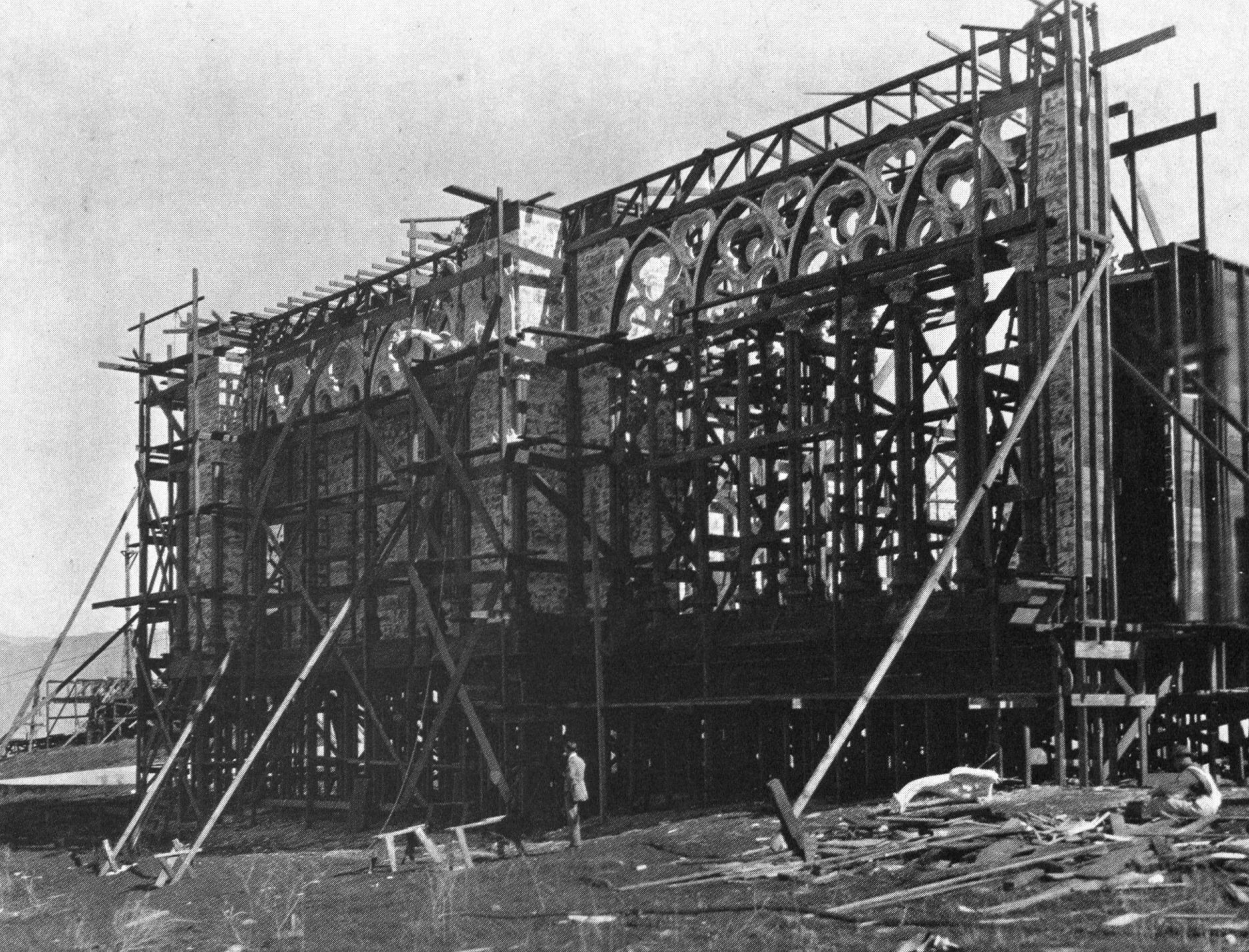

The framework was set up by 200 carpenters while sections of the facade were cast in concrete. Finn Froelich, a well-known sculptor, was in charge of making the bas-reliefs, embellishments, saints, martyrs and gargoyles that cover the Gothic structure. Before completion, the cathedral resembled a huge wooden shed, but when the lumber was removed, it had become a replica of the original exterior or, at least, the bottom 60 feet of it. After the masons finished their work, 60 painters added the finishing touches.

At the time of the story, Notre Dame was 150 feet wide and 225 feet high (the spire was added at a later time). The cathedral ended at a point just above the huge arch over the center entrance. To show wider views of the cathedral, the upper portion was constructed as a large-scale miniature that was mounted between the camera and the building and lined up to blend perfectly with the full-scale set. The complete cathedral, seen from several angles, defies detection.

Other parts of the building, for use in close-ups, were erected at different locations. Part of a tower was built full-scale on a hilltop about one mile away. The hill provided the elevation needed for low-angle shots but, as Patsy Ruth Miller says, “It was built so that you couldn’t hurt yourself if you fell.” The Bastille and drawbridge were built about a quarter of a mile from the courtyard. The gardens of the castle were located adjacent to the studio nursery, where the varieties of plants could be moved conveniently. Concrete arches were built over the Los Angeles River, which forms the northern boundary of Universal City, to represent the sewers of Paris. At that time the river bed was not concrete as it is today, and it was used in many pictures. When it appeared as the Seine, the Thames, the Danube or the Mississippi, the semi-arid river had to be dammed up or even irrigated by the studio fire department.

The principal sets covered 19 acres, 11 for the courtyard and cathedral and eight for streets and the Court of Miracles. The buildings included a castle, a hotel, shops, taverns and houses. Construction took six months. The settings and properties cost about $500,000-$342,869 of which was for the Place du Parvis set.

In Movie Weekly for April 21, 1923, Grace Kingsley describes a visit with Chaney to the set, where they “sat in the 11-acre-square of Notre Dame, facing that wonderful cathedral.

“We had driven up in Lon’s Cadillac! Imagine the humble hunchback driving a Cadillac! Around us sprawled or lounged a thousand extras... They were all in bright colors, and they formed a marvelous picture against the backgrounds of church, shops, old-fashioned houses of Paris, which themselves were silhouetted against the green hills of Universal City and the purple mountains in the distance.”

Perley Poore Sheehan, co-author of the screenplay, described the atmosphere more poetically in Cinema Art of January 1924:

“The cathedral towers would shimmer in a blue radiance like that of a thousand moons and send back echoes of coyote calls. Wouldn’t Victor Hugo have loved all this? I believe so. It was his sort of stuff. It was great and weird. I myself like to believe — and I do believe it — that the great Frenchman’s spirit presided over the filming... from the very inception of the idea right up to the premiere opening on Broadway.”

Sheehan had lived in Paris for 10 years “under the very shadow of the old cathedral” and just around the corner from Hugo’s house.

Jack Rumsey, “recently returned from Hollywood,” told the New York Times (July 1, 1923) that “the immensity of the sets and their accuracy was far beyond the ken of most persons” and that he “felt quite nonplussed when he stood before the great gate of Notre Dame in Universal City ... All the atmosphere of Paris was near the cathedral, and every little detail has received attention in making the copy in far off California...”

Sheehan, in addition to his writing duties, worked as a technical supervisor for Worsley. It was he who set the tone for the costuming with this directive:

“We don’t think of Christopher Columbus discovering America ‘in costume.’ We don’t allow ourselves to think for a moment of Notre Dame's 15th-century people as wearing grotesque costumes and having queer costumes. No costumes were grotesque to the people who wore them. They were natural, everyday clothes. Our characters must wear their costumes as such. The costumes... will be incidental and the main object is to make them and use them so that the spectator will forget them. They must be incidental — accurate, correct, but inconspicuous.”

Three thousand costumes had to be specially made. Planning and measurements were completed about a month before shooting was to begin. A building on the lot, which was 125 feet long with 18 windows, was enlarged to about double that size to handle the large number of costumes to be handed out to the extras at the windows. Around 200 men were necessary to handle wardrobe duties. Col. Gordon McGee, of Western Costume Company, supervised costume research and production. The fancier clothes were worn by characters of the court, the 50 men and 50 women attending the grand ball at the mansion of Madame Gaundalaurier, Esmeralda, and certain of the Gypsies. The more conspicuous extras were put on the payroll two days early so they could become accustomed to wearing their costumes in order that they would behave on camera as though they were wearing the normal clothes of their day.

The most unusual garb is that of the underworld denizens of the Court of Miracles. Because their home was surrounded by old palaces, these thieves and beggars wore garments pilfered from the nobility, especially during the plague when many of the rich abandoned their homes until the danger had passed. The beggars, therefore, wore the raiment of royalty, however soiled and tattered. The appearance of reality achieved in Hunchback, as opposed to the comic-opera look that contributed to the public’s dislike of most historical epics, may be traced in large measure to the authentically drab costuming.

Lon Chaney had been a colorful part of the ambiance at Universal since its early days, first as an extra and bit player and eventually as a featured actor and sometimes writer and director. He was one of several actors (others were Jack Pierce, Cecil Holland and C.E. Collins) who stayed busy by bringing their own makeup kits to casting calls and making themselves up on the spot to fit whatever kinds of characters were being cast. Since Universal specialized in Westerns, serials and jungle melodramas, Chaney played many a scar-faced heavy, also appearing as elderly men and paunchy fathers in society dramas.

Chaney, after a salary dispute, left Universal and found greater fame at Paramount, Goldwyn and other companies. When he returned to do Hunchback, he was a major star, earning the then-munificent sum of $2,500 per week. This picture brought him even greater stature, and when the Metro-Goldwyn company was formed in 1924, he was their first star. He returned to Universal for the last time that year to make The Phantom of the Opera, thereafter working for MGM exclusively. He died in 1930 after making his only talking picture, The Unholy Three. Ironically, his two most popular pictures were Universal’s Hunchback and Phantom.

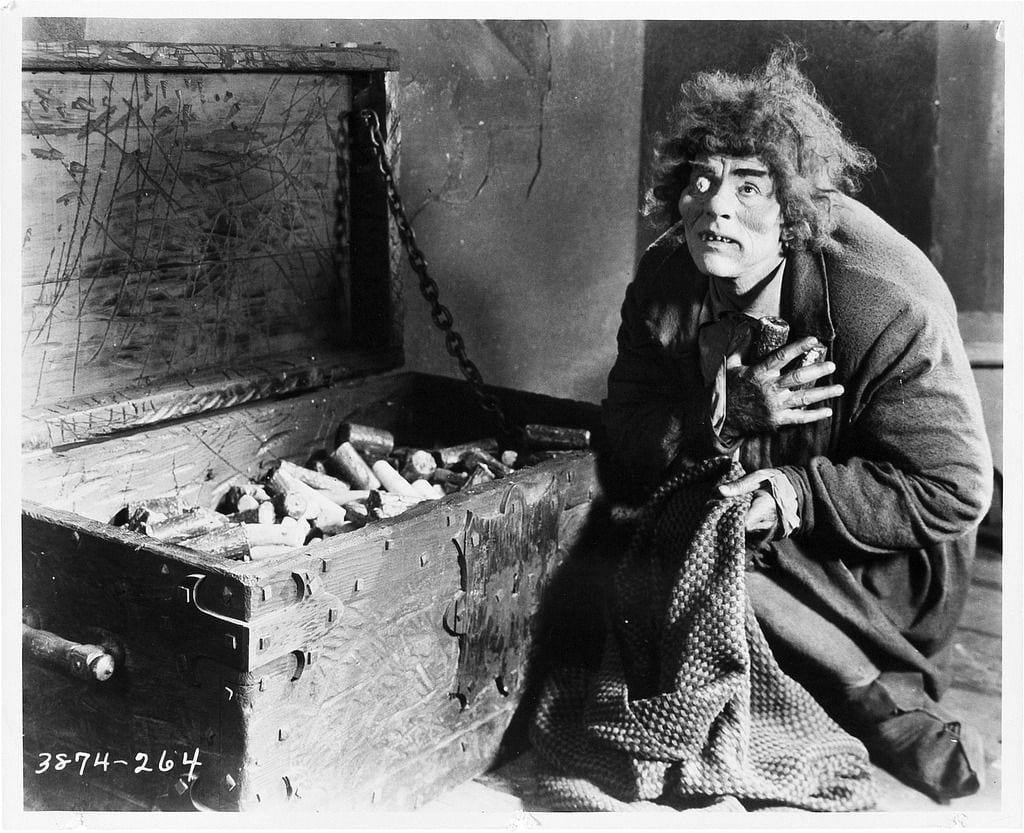

Checking in at Universal, Chaney appropriated Dressing Room No. 5, a new one-room shack, with a shower, on the front lot. Locking himself in with his makeup kit, two chairs, an iron cot, a wardrobe, a small table and a makeup mirror, he worked out the details of Quasimodo. His personal manager, A.A. Grasso, had borrowed for him an old edition of Hugo’s book which contained eight drawings of the hunchback by Hugo himself. Using these and Hugo’s vivid verbal descriptions, Chaney emerged at length with a Quasimodo which seemed akin to the monstrous gargoyles of Notre Dame.

This initiated a studio tradition regarding No. 5 which persisted until it and similar cubicles made way for more modern structures. Chaney returned there to create The Phantom of the Opera in secrecy. In 1928 the room was commandeered by Jack P. Pierce, head of makeup and a great friend and admirer of Chaney. Pierce created there Conrad Veidt’s horror makeup for The Man Who Laughs. Later he worked in secrecy in No. 5 on Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi, Lon Chaney Jr. and others who portrayed monsters of various sorts in the studio’s popular horror movies of the 1930s and ’40s. No. 5 was known as the Bugaboudoir and engendered a certain superstitious awe among some of the old-time Universalites.

“When Chaney first put on his makeup — The Hunchback is his life’s dream and every bit of his 15 years’ intensive study of makeup goes into it — Jack Freulich, studio photographer; Henry Freulich, Graflex cameraman with the publicity department; Fred L. Archer, head of the art title department and internationally known for his prize-winning studies, and two other photographers shot photographs simultaneously of the remarkable Quasimodo,” American Cinematographer reported in February, 1923. This was the first photographic job for the youthful Henry Freulich (later ASC), son of Jack and a celebrated director of photography in later years.

The other major roles were assigned to Patsy Ruth Miller, an excellent young actress who already had played leads in more than a dozen pictures, as Esmeralda; Norman Kerry (died 1956), who had been in pictures since 1919 and had just scored a big success in another spectacular production Merry-Go-Round, as Phoebus; and Ernest Torrence (died 1933), a tall, lantern-jawed Scottish opera singer, as the beggar-king, Clopin. All three are strong assets to the picture, and Torrence’s characterization is almost as impelling as Chaney’s. In fact, several who saw the original premiere engagement version have stated that Torrence’s role was severely cut when the film was edited for release and that he dominated much of the long edition, which no longer is available.

Robert S. Newhard, ASC was named first cameraman (today he would be called the director of photography). However, the magnitude of the Hunchback production was such over a long period that almost every other cinematographer at Universal had a hand in it at various times, including Charles Stumar, ASC; Stephen S. Norton, ASC; Anthony Kornmann, ASC; Virgil Miller, ASC; Friend F. Baker, ASC; Philip H. Whitman, ASC; and perhaps a dozen others. Only Newhard received screen credit.

A founding member of the ASC in 1918-’19, Newhard had been a cinematographer for about 13 years, having begun as an assistant to Fred Balshofer at the 101 Bison Ranch. He then became one of the earliest special effects specialists, heading an experimental and research department for Thomas H. Ince. One of his most striking efforts was a Billie Burke feature filmed entirely without artificial light by use of mirrors and reflectors. After shooting 14 features for Ince in four years, he worked for Paralta, Frank Keenan, Selznick, Fox, and Goldwyn. He teamed with aviator Frank Clarke in making aerial films, then was called to Universal for his biggest assignment: six months’ work on Hunchback. It proved his magnum opus, a film whose photographic qualities (even in the much-copied 16mm prints which seem to be all that remain) are remarkable even today.

Newhard hailed from rural Pennsylvania and, since boyhood, had been fond of keeping snakes as pets. Snakes were abundant in the grassy and (then) largely undeveloped Universal backlot, and a six-foot gopher snake became Newhard’s companion during the last two weeks of shooting. Most of the cast and crew gave the cameraman’s friend a wide berth.

Anthony Kornmann ASC, also worked as a first cameraman on many scenes, although it is now impossible to determine which ones. Kornmann was a second unit specialist during most of his career. Hungarian-born Charles Stumar, the most famous of the cinematographers who contributed to the film, was another veteran of the Inceville studio and is believed to have shot some of the softly romantic scenes between Esmeralda and Phoebus. At the height of his career, in 1935, Stumar was killed in an airplane crash while scouting locations. Stephen S. Norton, ASC — a diminutive cameraman who at the time had photographed more than 160 features, several serials and innumerable short films — lent his expertise to some of the mob action scenes.

Phil Whitman, another ASC member, and Friend Baker had been working with designer Sheeley in developing special effects techniques for Universal. They were responsible for the flawless glass shots and hanging miniature effects which expanded the scope of the settings enormously, completing the job of transforming the backlot into old Paris. They also filmed, at considerable expense, a fantasy sequence depicting Phoebus’ fevered dreams during his delirium, which was not used in the final cut because studio executives found it confusing. (Whitman, who eventually switched to directing, is best known for his special effects for Douglas Fairbanks’ The Thief of Bagdad of 1926, and it was Baker who staged the earthquake for the 1927 Old San Francisco).

Virgil Miller, ASC, who died in 1974, considered Chaney “really one of the greatest.” Miller said, “I remember when we were both working at Universal and I was getting $18 a week and he was getting $35. One day he said, ‘Virg, I’m going to hit ’em for a raise.’ That encouraged me and I told him I would ask for a raise of $2 a week for myself. We went to Mr. Laemmle and he was refused his raise and so he left Universal. I got my increase and stayed.

“A few years later, with Chaney an established star, the studio wanted him and no one else for The Hunchback. He wanted me on camera, so I sat in on the conferences. I was delighted to hear my old friend hold out firmly for an added $35 to be called for in his contract. He got it, too. His checks were made out for $2,535 every week — quite a raise!”

Chaney demanded that Miller should do all of his close-ups. Miller had photographed Chaney in The Trap (1922), one of the earliest pictures to use panchromatic film, and Chaney liked the close-ups better than those in his other films. Miller was also involved in some special effects and some of the large-scale action.

“Once, when Chaney was at the top of the cathedral set and I was down below at the camera, I noticed that he was still wearing his wristwatch,” Miller recalled. “I signaled wildly and spelled out ‘wrist’ in sign language, which he understood because his parents were deaf, and he stuffed the watch out of sight. After that, I always checked him out with the six-inch lens so I got a good close look before we started. I hated to see him have to do the rough scenes over if he didn’t have to.”

Chaney was himself an enigma. Secretive, uncommunicative and unfriendly much of the time, he could be a staunch friend as well. His first wife considered him an implacable and unforgiving enemy and his son suggested he could be terribly cruel.

“I remember his kindness,” Patsy Ruth Miller said of her work with Chaney in Hunchback. “I was only 17, and he was extremely kind and very helpful to me, which is certainly not true of all the big stars of that time. He was very serious when working, but had a fey sense of humor. We were working at night on the underworld set and it was about 1 a.m. when they got to my scene. It was dark and foggy, and the klieg lights gave it an eerie look. I had just started when, all of a sudden, a monstrous creature came leaping out from between two buildings and scared the daylights out of me! When I was through screaming I realized it was Lon."

“During preparations for one of the big emotional scenes, he said to me, very quietly: ‘Remember, my dear, you are an actress. You don’t have to live the part, just act it. The point is not for you to cry; make your audience cry. You have to be in control of yourself.’ When Norman Kerry and I were doing the scene where he is trying to seduce the Gypsy girl and he’s offering me wine and I’m looking calf-eyed, Lon came in off stage and said, ‘Oh, Mr. Kerry, are my eyes too big for pictures?

“Lon did a lot of directing on his films. He wasn’t a very social man. I never saw him out socially, anywhere.”

Jackie Coogan, who worked with Chaney in Oliver Twist in 1922, described him as “very short, very tan, bowlegged — a rough man, a tough man. A real loner — he made Howard Hughes look like Pia Zadora.”

Grace Kingsley found Chaney without makeup “very good-looking, very charming, very well-dressed. You’d never recognize him if you met him on the street.” As she wrote:

“‘In one way,’ he explained, as we watched the extras flock over to the set, ‘makeup helps you in putting a characterization over. It aids you in getting into the spirit of the part while you are looking into the mirror, and when you see the interest in the faces of your co-workers. But in another way it hinders.’

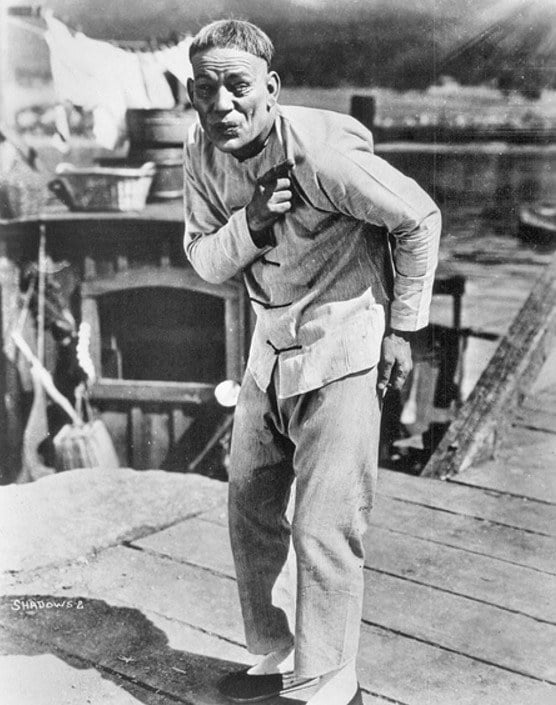

“‘When a makeup is as painful as that which I wore as Blizzard in The Penalty, when I had my legs strapped up and couldn’t bear it more than 20 minutes at a time — when I have to be a cripple, as in The Miracle Man, or have to keep a certain attitude of body as I did in playing Yen Sen in Shadows, it sometimes takes a good deal of imagination to forget your physical sufferings. Yet at that, the subconscious mind has a marvelous way of making you keep the right attitudes and make the right gestures when you are actually acting.’

“‘But there’s another thing. Though makeup helps the illusion in the minds of the audience, too, still it sometimes requires 10 times the concentration to get results when a grotesque makeup is used, inasmuch as the face, in its set lines, must necessarily fail to register many expressions.’

“‘And when it comes to a character like the Hunchback, which demands that the audience sympathize, despite his repugnant looks — well, it is the hardest part I ever played, that’s all.’

“‘You see, I am following as closely as possible the best-known illustrations of Hugo’s novel. Therefore, I am hunchbacked, knock-kneed, have one eye almost entirely closed by a big wart, have a hairy skin, and am altogether repulsive to look at. But this isn’t all. I wear a cast that weighs about 50 pounds, and which, doubled up as I am, it is nothing short of agony to carry around.’

“Can’t you take off your makeup and rest once in a while?" I asked.

“‘What? When it takes me three hours and a half exactly to put it on?’ demanded Lon. ‘I should say not! But at that, I cannot stand the makeup longer than six hours at a time. Yet I must not only get interest in the Hunchback; I must get the deepest sympathy for him from my audiences, else he fills my onlookers only with revulsion and disgust. But the thing I dread most of all is not the putting on of the makeup, not even the wearing of it, but the taking it off. See all the hair gone from my eyebrows? Pulled it out taking off my false eyebrows. And my eyelid is all burned from the application of strong glue. Also, I’m sure I’m permanently warped about the shoulders from carrying that hump on my back.’”

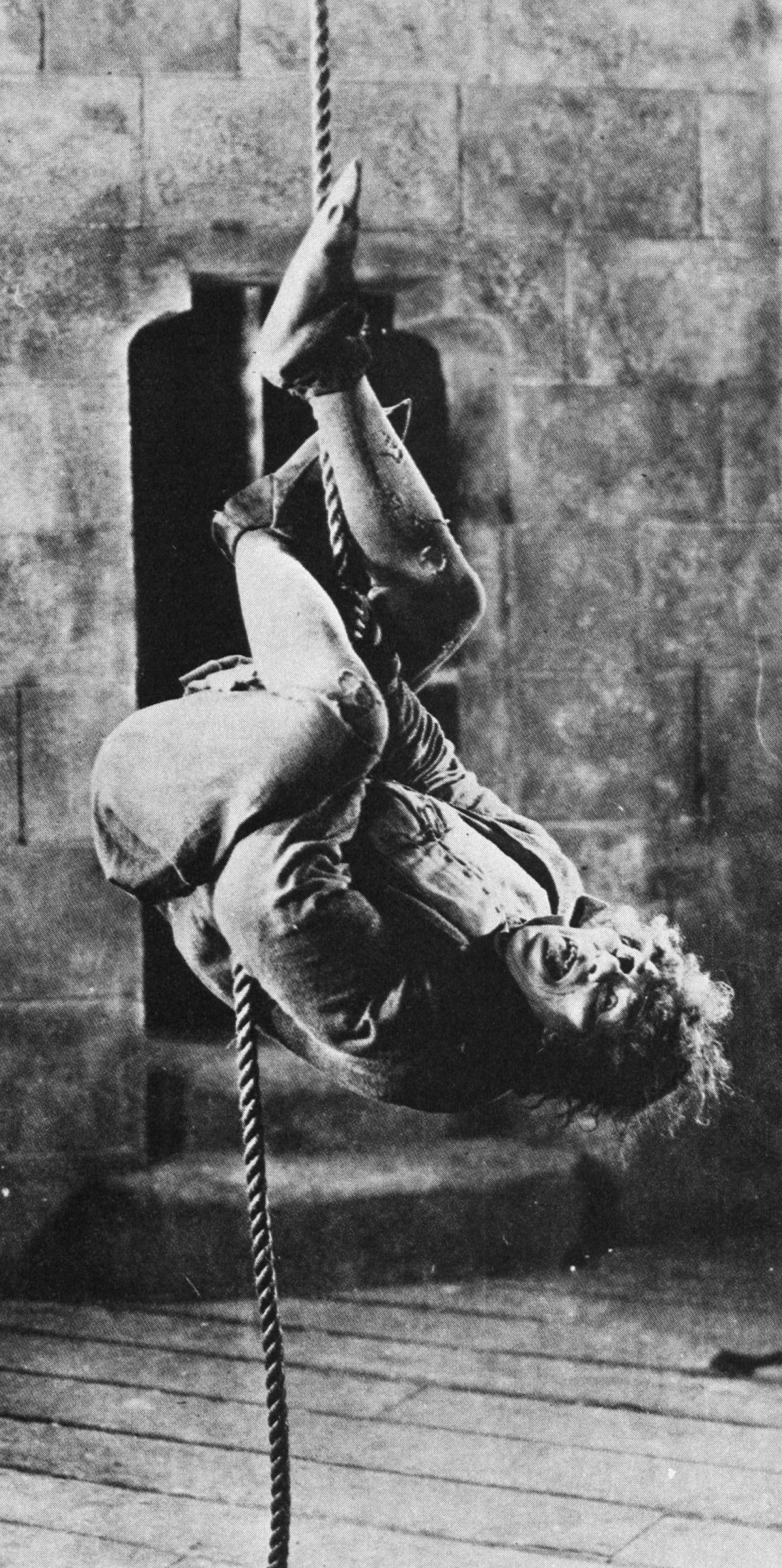

Actually, there is one major difference in Chaney’s Quasimodo and that of Hugo. The author described a giant of a man who had been put together badly. Chaney, being of no more than average size, opted for a misshapen dwarf, a concept the public accepted without complaint. His performance is above criticism, a masterpiece of pantomime investing an initially terrifying creature with endearing qualities. It should be noted that despite his many deformities, the hunchback possesses great strength and agility. Instead of “hamming it up,” as actors in heavy makeup often do, Chaney gives the impression that Quasimodo has learned to live with his condition.

Chaney was (secretly) doubled by Universal’s serial star Joe Bonomo in some of the more athletic scenes on the tower and in the climb down the facade to rescue Esmeralda.

Historically, the most remarkable aspects of the picture are the lighting and photography of the night scenes, which are far more sophisticated than any previous efforts of this kind. As Harry D. Brown, who headed the lighting crew, said in American Cinematographer (October 1923), “The exact reproduction of the cathedral of Notre Dame on American soil at Universal City... was in itself a triumph for the motion picture technician, but in spite of all the faithfulness with which the reproduction was executed, it could not have been brought to the screen if it were not amply illuminated so that it could be photographed properly.

“There was no precedent by which the electrical engineer or the chief cinematographer could be guided. The entire illumination and proper photography were matters that they themselves had to figure out, and succeed or fail according to their own judgment.” Brown stated that “success in filming this record-size set depended basically on the human angle; that is, all the artistic and technical attainments would have been naught had the cinematographic and electrical divisions not worked in harmony so that efficiency in the two departments aided rather than hindered.

“Bob Newhard, a member of the American Society of Cinematographers... is an artist of the highest quality as proved by his splendid photographic achievement in The Hunchback. More than that, he is a prince among men, and during the six months that we worked on the picture, there never was a controversy of any kind between the cinematographer and the electrical department, although at times the natural difficulties involved in the making of the picture were such as would test the evenest of tempers. As photography is one of the outstanding features in this production, Newhard cannot be given too much credit for his work.

“In the first sequence, that of the ‘Festival of Fools,’ the illumination had to be of such an intensity that would permit us to shoot the same shots with considerably less light and a great deal more in later scenes. Baskets of burning substances being the source of light, scenes were staged in the dead of night with the buildings all dark and no sign of life, when we had mobs to rush in suddenly from all sides with burning torches, starting bonfires and setting buildings on fire. To light, this action atmospherically correct required not only a different intensity of light but made it necessary to gradually raise the illumination as the mobs advanced on the palace and the cathedral.”

Used in filming the festival were 37 sunlight arcs, five GE spots, 154 Winfields and 47 overheads, plus 62 practical arcs for the baskets. Much more complicated was the lighting for the “moonlight and torches” scenes, described by Brown as follows:

“...We started with 15 sunlight arcs and 10 120-ampere spots, the 15 sunlight arcs burning full capacity with 37 sunlight arcs burning at very low voltage. As the mobs advanced with their torches, the voltage was raised to a certain intensity, gradually increasing when they started the bonfires, again raising a little more when the buildings were set on fire, while in the meantime the windows in all of the buildings were lighting up. By the time the scene had progressed to its height all sunlight arcs were burning at their full capacity, every window was lighted and the entire set was one blaze of light for fully 10 minutes. The total amount of equipment burning was 52 sunlight arcs, 21 GE high-intensity spots, 30 120-ampere spots, 47 overheads, and 249 Winfields."

“To supply energy to this equipment required seven motor generator sets, two of which were of 300-kilowatt capacity, and three gas-driven power wagons, which gave a total of 24,000 amperes actual load. This energy was distributed to the various parts of the set over approximately five miles of stage cable and feeders, terminating in 16 location switchboards, and from there to the different pieces of apparatus. The energy was transmitted from the main sub-station at the front end of the plant through one mile of 2200-volt feeders.”

Earl Miller was chief gaffer in charge of the electrical crew, consisting of 139 men working under nine divisional foremen. Separate crews handled lights and feeders to save time when changing setups. Miller noted that “all during the period of production we had 17 other companies shooting on the lot. We had to furnish them with men and equipment, too, bringing the total to 230 electricians on the payroll and practically all the available equipment in Los Angeles.”

Harry Brown was one of the finest electrical experts in the studios. A Spanish-American War veteran, he built the first large electrical signs in America at Atlantic City in 1901, and later pioneered in designing animated signs in Los Angeles. He built the first portable generator and developed the first radioactive machine for the treatment of cancer.

The chief gaffer was Earl Miller, who reminisced about the picture 17 years later, when as chief electrical engineer of RKO-Radio Pictures he worked on a new version of Hunchback (in American Cinematographer, February, 1940): “What a winter that was; rain, fog, wind, and mud — days, weeks, months of it. ‘The largest artificially lighted motion picture set in the world,’ they told us.

“Believe me, when I recall those foggy cold nights and the miles we walked, night after night, up and down that cobblestone street and out in the mud, I wonder how the picture was ever completed.

“In 1923, incandescent lights were not used for motion pictures. The street set was a few feet longer and wider than the one used in the 1939 version. There were only 56 24-inch sun arcs in the entire industry in Hollywood.

“We needed everyone for our night shots and Universal arranged to rent all but one. Every night for seven long weeks all the sets in other studios were stripped of 24-inch sun arcs. They were loaded on trucks and hauled to Universal. We used them until 5 a.m., but had to return them to the proper studio and have them set up and ready to burn by 8 a.m. Whenever possible we left the lights on the trucks all night instead of building parallels...

“Every light... was an arc. Some of the 24-inch had automatic feed, but in addition to these there were more than 450 other arcs, all of which were hand fed. All lights had to be trimmed at least twice every night and some three times. Yes, we actually shot every night, all night, for 49 straight nights. At one time (and it would be the time it rained the hardest) my crew and I worked five days and six nights straight, rigged all day and shot all night; never took our shoes off; catnapped between shots."

“Finally... the last reel was in the can, and in spite of all the work and worry everyone who worked on or in that picture will tell you that we had lots of fun making it.”

C. Roy Hunter, head of the camera and laboratory departments, said that approximately 750,000 feet of Eastman negative were exposed. The approximate ASA daylight rating of that emulsion would have been 12. The lenses used were no faster than f:3.5; many were E4.5 lenses.

Hunter said that “there was one day when the cameras totaled 26. They were grouped in pairs.” (It was customary at that time to photograph everything with paired cameras, one of which shot the negative to be sent overseas for the preparation of foreign prints. This affected an enormous saving in shipping and customs costs as compared to sending release prints. Cinematographers were designated as first and second cameramen for this reason.) “The occasion was the engagement of 2,500 extras. Unknown to these extras they were to be attacked by 500 horsemen in tin armor and driven onto the steps of the cathedral. The plan was to create a panic. The plan succeeded — in full.

“Every precaution was taken to avoid accidents. First aid stations were established at convenient points, while surgeons and nurses were allotted. The 500 horsemen precipitated a most realistic mob scene when the word was given for them to move in. Terror and pandemonium reigned, speaking truthfully. But the precautions that had been taken worked to a charm. Almost. Of all the close calls and narrow escapes from injury only one required the attention of the surgeons and nurses. And that was a horseman who inadvertently fell from his mount and thereby broke a leg.” (American Cinematographer, February 1940).

Before the scene with the 2,500 extras, 500 horsemen and 26 cameras was shot, Worsley announced that he would demand a retake of the entire day’s work should any one of the cameramen fail to get the expected result. This so unnerved one cameraman that, after shooting the slate with his 3" lens, he failed to remove the cap from the 2" lens with which he was supposed to shoot the action. Hunter, upon seeing the rushes, quickly had an extra print struck of the film shot by the camera nearest that of the unlucky cameraman and attached it to the latter’s slate shot. When Worsley viewed the rushes, carefully noting the name of the cameraman on each slate, he was forced to admit that every one had performed admirably. Hunter estimated that the scene would have cost about $30,000 to restage — enough money to finance a couple of the profitable six-day Westerns that were Universal’s main source of bread and butter in those days.

Principal photography, which had begun on December 16, 1922, was completed on June 3, 1923. About 750,000 feet of negative was exposed. Editors Maurice Pivar, Sid Singerman and Ed Curtiss cut from this an unusually long picture — 12 reels — which would be released to key theaters only at a stage-play ticket price.

Fred Archer prepared the art titles, which were largely hand-lettered and illustrated in opaque tempera.

The completed negative was shipped via armored car to the Universal vaults, at 1600 Broadway in New York, around August 1. Accompanied by one of Laemmle’s executives, James V. Bryson, and an armed guard, it was insured for $1.5 million, which approximated the actual cost.

One print was struck for the use of Dr. Hugo Riesenfeld, Viennese-born violinist-composer-conductor-impresario, at that time the most famous of the movie theater musical directors. Riesenfeld prepared what he called a “musical setting” — a compilation of classical themes, music composed for adaptation by theater orchestras, and original compositions, which were arranged into a closely keyed accompaniment for the film. The music was scored for a symphonic orchestra and also arranged for small ensemble and keyboard solo.

The published score was made available to theaters that booked the film.

Release prints were printed on Eastman-tinted base stocks. This type of color was not intended to resemble what was called natural color processes, such as Technicolor or Kinemacolor, but was designed to intensify the changing moods of the drama. The transparent colors of the film base provided a tint under the black and white images — amber for the candlelit interiors, blue for night effects, peach glow for the romantic scenes, a garish green for the torture chamber and the evil plottings of Jehan, and magenta for the flashback sequence about the kidnapping of Crazy Godule’s child. In some instances the images were toned as well, producing a blue on blue for some of the night scenes, sepia on amber tone, and, for the torture scenes, a blue tone over a green tint that is appropriately hideous.

The premiere was held at Carnegie Hall on August 30, 1923. Proceeds were donated to the American Legion’s fund drive for a mountain camp for veterans. Regular showings at advanced prices began at the Astor Theater on September 2. The picture received excellent reviews and drew huge crowds. Laemmle was so pleased that he commissioned an Austrian sculptor, A. Finta, to make a bust of Chaney as Quasimodo, which was installed in the lobby in anticipation of a long engagement. A special program was held at the Astor to celebrate the 100th performance on October 22, and another for the 200th showing during an entire week of late December. The picture was about 12,000 feet long during this special engagement, with a running time of 320 minutes. It was later cut to about 10,000 feet.

On February 17, 1924, Hunchback left the Astor to begin its first regular-price release. Carl Edouarde, musical director of the Mark Strand Theater in New York, assisted by composer-orchestrator Cecil Copping, arranged an entirely new score for a 50-piece orchestra, mixed chorus, soloists and chimes. Domenico Savino composed the “love theme,” “Twilight Hour,” and classics by Arcadelt, Suk, Delsaux, Fourdrain and others were utilized.

In 1929, plans were formulated to remake Hunchback as a talkie, utilizing the same sets and props that had been created for the original. Chaney, now under contract to MGM, was not available to re-create his role, and the other actor considered for the part, Conrad Veidt, returned to his native Germany after hearing his heavily accented performance in the part-talking versions of two other films. The Depression had placed Universal in financial straits which made production of a picture of such scope impractical, so Laemmle had to content himself with a reissue of the original with a new musical score synchronized on disks. Recorded under the supervision of Roy Hunter, the orchestra was conducted by Heinz Roemheld with original music by Roemheld and Sam A. Perry augmented with library music.

Remake plans resurfaced in 1931 with Bela Lugosi as the prospective Quasimodo. A new script was written and during the next four years Boris Karloff, Henry Hull, Peter Lorre and Edward G. Robinson were mentioned as possible Quasimodos. The project was still pending at the time Universal was bought by a group of financiers in March 1936. With the departure of the Laemmle family and friends, the new owners set about establishing a new image in which Gothic spectacle had no place.

Three years later, Hunchback was remade, superbly, by RKO-Radio, with Charles Laughton. RKO built a new cathedral and environs at the RKO Ranch in Encino. A French version, released in the U.S. in 1957, featured Anthony Quinn and Gina Lollobrigida.

Universal’s Paris sets saw a great deal of use until the cathedral and most of the other buildings were destroyed in a fire in the 1960s.

After more than six decades, the 1923 film has attained almost legendary status. Laemmle’s long-time right-hand man, Robert Cochrane, said an interesting thing about it a long time ago:

“The great pictures... were, almost without exception, productions which never would have been made if the question of whether or not they should be attempted had been left to a popular vote. You could count in a minute all the people who predicted the great success of The Hunchback of Notre Dame.’’

AC’s 1923 article on the costumes for the production can be found here.

A new Blu-ray version of this restored classic was recently released by Eureka! in the U.K.

For access to more than 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.