Instinct: Enlightening Illumination

Cinematographer Joe Collins offers clues on how he depicts the inner workings of a genius mind in this inventive crime drama.

Cinematographer Joe Collins offers clues on how he depicts the inner workings of a genius mind in this inventive crime drama.

Unit photography by Francisco Roman & Jeff Neumann, courtesy of CBS

Dr. Dylan Reinhart enjoys his life these days as a renowned professor and author in criminal behavior analysis. But when NYPD detective Lizzie Needham calls on him to assist in a serial murder investigation, the former CIA operative can't resist an opportunity to get his investigative juices flowing again in the CBS mid-season series Instinct, starring Alan Cumming and Bojana Novakovic.

The show is based on the James Patterson book Murder Games. Creator Michael Rauch wanted his longtime Royal Pains series cinematographer Joe Collins to shoot the pilot episode. Collins, however, was tied up, so Jimmy Lindsey, ASC (Revolution, Limitless, From Dusk Till Dawn) filled in admirably. When Instinct was picked up to series, Collins was free to shoot the balance of the 12-episode season starting in July of 2017.

After the pilot, the show executives wanted to make some tweaks to the visuals, including adding more camera movement, decreasing depth of field, adding some warmth to the lighting and highlighting Dr. Reinhart's problem-solving mental gymnastics. That last one left Collins wondering: “How do you film the cognitive process?”

“He's able to take a ton of facts, process them and come up with a solution — you know, put all the pieces of the puzzle together,” Collins says. The show creatives were inspired by how Sherlock, the BBC series starring Benedict Cumberbatch as the famed sleuth, addressed the same issue, and Collins turned to Panavision New York for assistance with the technical aspect of visualizing Reinhart's thought process.

Seeking his own solution, Collins tested the new large-format 8K Panavision Millennium DXL with Primo 70 spherical prime lenses. It was the only DXL body Panavision had at the time that wasn't spoken for. After the proof of concept was presented to CBS — including visuals, on-set data management, and the high-data workflow by Technicolor-PostWorks NY — the network gave the go ahead to shoot at 8K and 6K resolutions.

Explains Collins, “Because we were establishing a new way of visually piecing together thought, and because we wanted to allow the producers and CBS the most leeway in post, should they decide that the scripted way of Dylan solving a crime didn't work, they needed room to adjust after the fact. This meant that if Dylan remembered a clue as scripted, and we shot only that, if it was decided later that there was a better clue or the storyline changed, then we were stuck with only what was shot. So, to ensure the most freedom for all, we knew we had to shoot 8K for these moments and allow post the ability to isolate multiple parts of a single frame should changes arise. We also wanted these pieces to stand out from the rest of the show visually, and we opted to use an anamorphic adapter on the lenses and added a Schneider Blue True-Streak filter to all ‘Dylan Pops,’ as they were called. We also shot these pieces at 48 frames per second to slow the moment down and/or to allow ramping. The last piece was a lighting cue to signal the transition into Dylan’s mind, and for that we used a Jo-Leko, which would flare the lens as the rest of the lighting would dim around him.”

For gaffer Pat Fontana, those lighting cues were challenging. “I feel that the most difficult lighting setups were when we utilized the 800-watt Jo-Leko to try and flare the camera lens for those special show elements,” he says. “A Jo-Leko is the combination of two lights — the reflector housing of an 800-watt K-5600 Joker HMI is removed and with an adapter the backing is attached to an ETC Source Four, which is normally a tungsten unit. Lekos have many lens barrels that have different beam widths that can be easily swapped out from the Leko body. The lens systems create a sharp falloff in lumens outside of the beam edge, much like a spotlight.

“We would use the 19-degree lens for our flare purposes,” Fontana adds. “Because we shot on spherical lenses and not true anamorphic, the camera department attached an anamorphic adaptor, that, like a Polarizer, needed to be orientated in the proper fashion so that the flare would be horizontal in the frame. We would place the Jo-Leko on a stand and rake the camera lens with the attached anamorphic adaptor to achieve the artificial flare. It was challenging to achieve the exact look desired because we needed to move the light around the frame to find the sweet spot of the adaptor. It was sometimes problematic because we also were trying to keep the equipment out of frame to a certain extent. When the gag worked, it looked superb and the effort paid off.”

These “Dylan Pops” were shot at 8K (8192 x 4320) resolution with a RedCode compression of 8:1 and utilized a 46.3mm image circle when rendered at the lens’ wide-open aperture of T2. The DXL is built upon RED Digital Cinema’s Monstro sensor but employs Panavision/Light’s custom color science.

The rest of the show was shot at 6K (6144 x 3160) resolution with a RedCode compression of 7:1 and utilizing a 34.53 image circle — slightly larger than a Super 35mm aperture. Because only one DXL was available, B and C cameras were Red Weapon bodies with Dragon 6K sensors, to maintain visual similarity among all three cameras. The Red Weapons also were the ideal form factor for Steadicam use.

Collins adds: “Another reason we chose to shoot in 6K and 8K was that early on we were playing with the idea of having graphics, crime scene images, specially modified excerpts from scenes and flashbacks from Dylan's past, all swirling around him as he processed the clues. Shooting in this large scale allowed post a lot of freedom to play with this concept and lots of options for material to pull from. In the end, CBS opted to dial this back a bit, but by having this large amount of [image] data, we enabled them to fully explore all their options.”

As DIT Jeff Hagerman notes, “Our footage was shot in RedLogFilm color space, on top of which we applied a custom de-log LUT, and from there, any color decisions were made on a scene-by-scene basis using ASC CDLs through Pomfort LiveGrade Pro and Blackmagic Design DaVinci color-grading applications. Images were viewed on Flanders Scientific DM250 OLED monitors through Fujifilm IS-mini LUT boxes.”

Another reason Collins went large format was to provide the show creators the shallow depth of field inherent to that format. “While testing, I had Panavision de-tune the Primo 70 lenses to Level 3 Noir, a kind of softening but without lowering the contrast; I still had rich, dark blacks,” he says. “It was hard on the focus pullers, but John Reeves and Eric Robinson did an amazing job of keeping things in focus.” Collins had two full sets of Primo 70 large-format primes on hand to serve the three camera packages, which were operated by John MacDonald, Edgar Colón and Ted Chu.

More camera movement was introduced into the visual language, such as pushing in toward subjects or dollying across a room to find a character. “Even when things were stationary, like people seated at a desk, there always was just a subtle left to right to left movement, usually with something in the foreground,” says Collins. “It fits with the investigative style of the story as we constantly trying to figure out the crime with them.”

Between the pilot and the second episode, two locations were added to the show: Dr. Reinhart’s New York apartment and the police precinct, both created on stage by production designer Ray Kluga.

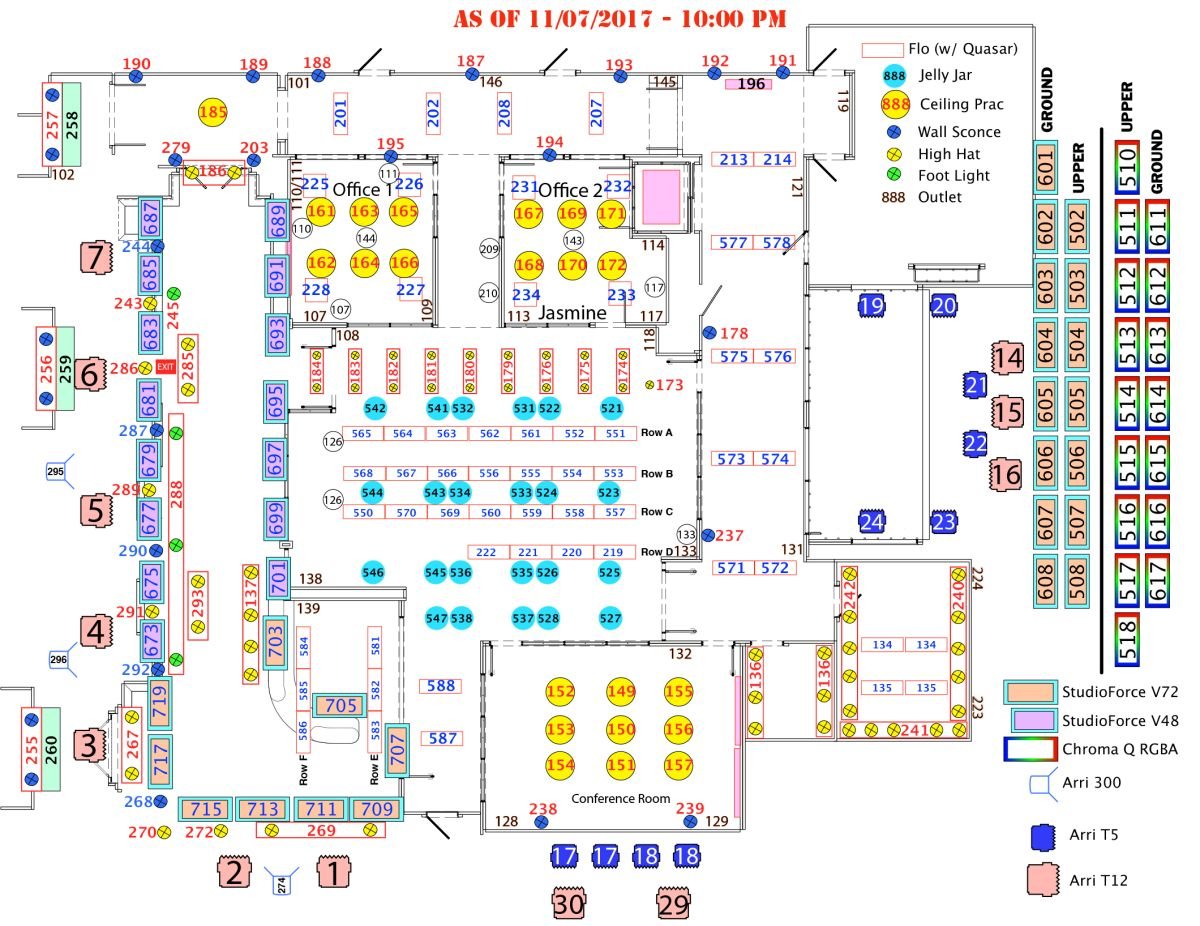

Says Collins, “The premise of the precinct set was that it was new construction, an independent addition attached to a much older NYPD building by a long, tall atrium, the cover of which was a ceiling of 10 or 12 large glass skylights. The idea was to contrast the older-style NYPD with the newer, state-of-the-art NYPD of 2018. The old building was aged, weathered stone and copper-lit by tungsten sources. The new building was glass, metal, tile and chrome, with LED and fluorescent lights, computer screens and monitors.”

The bullpen office area for the detectives was sandwiched between two hallways. One hallway was that tall, 16'-high atrium-type hallway. The opposite hallway had a large glass window array that was 20' wide and was backed by a Rosco soft drop. Fontana describes the setup in detail: “We utilized these two opposing hallway set elements to motivate our lighting in the entire precinct. The atrium hallway had Ultrabounce material stretched over the entire length of it at the pipe grid level. We employed 24 Studio Force hybrid LED lights to illuminate the bounce, which allowed us to dial in any color temperature we desired between 3200°K and 5600°K, to suit the time of day in the scene. These LED lights were rigged behind the set walls of the hall and just below the top of the wall so that the wall would act as a natural bottom cut for the fixtures, which kept any raw spill from contaminating the hallway. This bounce gave us a general soft ambiance that would pour into the bullpen. For hard light in the atrium hallway, we employed nine Arri T12 Fresnels, powered by an ETC Sensor dimming rack, and mounted them on a fixed-height track so that we could slide the fixtures left or right, parallel to the bullpen, to change the angle of the light to achieve a certain key or backlight angle with the lighting. During the initial build, my preference was to utilize Mole Richardson 10K LEDs so that we could dial in any color temperature; however, the units were still too new at the time of installation and wouldn’t be available in the numbers we needed. We settled on conventional Arri T12 Fresnels and attached half-blue color correction and half-white 250 diffusion to each fixture in the atrium hallway.”

“After the first day or two shooting in the precinct,” adds Collins, “We realized that the set looked best during day time to feel as if lit by daylight coming through the windows on either side of the precinct. We pushed deep into the interior with big sources that Pat mentioned, which were rigged above the exterior of the set. We used the practical lights as accents in the foreground and background, kill or dim the overheads, and enhance the sunlight feel with 5Ks or 10Ks skipping off white mat on the floor of the interior. We wanted to feel the light fall off as you got deeper into the set, but sunlight, highlights, floor bounce, and reflections were emphasized everywhere and they keyed the scenes. The atrium was tricky, but we the blue T12s rigged overhead and separated with cutters from the grips made a believable single source of daylight over the skylights. In general, the daylight from the exterior was always one quarter to half blue compared to the slightly warmer practical set lights. Ray had designed a woven metal sheet grid for our interior ceiling, with rows of modern hanging fluorescent fixtures lighting the precinct. Above the ‘see-through’ metal grid were long girders that we lit with tungsten ‘jelly jars’. Ray provided sconces and hanging fixtures to light the hallways, and the offices were lit by overhead fluorescents and a combination of floor and table lamps.”

Fontana turned his attention to the hallway on the opposite side of the bullpen, the one with the expanse of windows backed by the Rosco soft drop. “We called the area outside these hallway windows the ‘yard’,” Fontana says. “It was a 20' by 20' area, and directly above the open space in the yard was a 12' by 20' blue bounce, which was rigged with one side abutting the wall above the windows of the hallway. This was attached directly to the pipe grid and was surrounded on the remaining three sides with a total of six Arri T5 Fresnels, two per side, all powered by an ETC Sensor dimming rack. By using a blue bounce, we did not need to attach color correction gel to the lights to achieve our cool, ambient source.

“Also in the yard,” he continues, “we utilized three Arri T12 Fresnels, powered by an ETC Sensor dimming rack, which were mounted on a track that was affixed to box truss suspended by chain hoists and positioned between the drop and the windows, all parallel to each other. The chain hoists allowed key grip Matt Staples to fly the lights in for focusing which expedited the lighting process. These were slid left or right as needed so they could be used as either a key light or backlight. These lights were also treated with half-blue gels and half-white 250 diffusion.

“The Rosco soft drop was a day/night drop. When lit from the front, it gave the appearance of a daytime shot, yet when lit from behind, it appeared like a nighttime shot. The front/day side was lit with 15 Studio Force hybrid LEDs that were arranged parallel to the drop — we had eight units on the stage floor uplighting the drop and seven units rigged to the pipe grid downlighting the drop, all in a raking fashion approximately 5' away from the drop. We set these lights to 4500°K at 55% intensity for day work and 3200°K for the night look but at a much reduced level of intensity. Because soft drops are manufactured with fabric, unlike a traditional vinyl drop, they cannot be lit from directly behind or the lighting fixtures will be seen through the material. To light the drop from behind for nighttime, we employed 16 Chroma Q Colorforce 72 LED RGBA lights, also arranged parallel to the drop with seven units uplighting from the stage floor and nine units rigged from the pipe grid downlighting. Due to the type of lens in these lights, they were a foot off the drop. We only used the amber emitters — the ‘A’ in RGBA — which lent a gritty sodium feel to the cityscape, rounded out by the subtle tungsten front wash of the Studio Forces.”

The center of the activity, the bullpen, was lit with 50 4' T8 3200°K fluorescent tubes, placed in 4', two-tube modern-looking fixture housings provided by the set decorators. “Our original plan,” says Fontana, “was to place Quasar Science 4' T8 3200°K LED tubes in the fixtures; however, the manufacturer could not supply that amount of bulbs. The T8 size was a new item for them, and they did not have production lines up and running in time for our delivery deadline.

“Our shop electrician, Rich Cohen, worked tirelessly to revamp the fixture housings so that they had a high-frequency, dimmable electronic ballast that we powered from an ETC Sensor dimming rack. This gave us the capability of a 60-percent dimming curve with the fluorescents. Because we shot at 60 frames per second on occasion, this was a necessity with the fluorescents. Each fixture had its own isolated dimming circuit, which gave us a great amount of control of the overhead lighting.

“While shooting in the bullpen,” Fontana says, “any units that were directly overhead of actors were turned off, and more flattering light was added on the ground. We mostly utilized Arri Skypanel S60s and S30s for ground use, and generally pushed them through 4' x 4' diffusion frames outfitted with a Light Tools soft crate to control the light. We patched these into the dimmer board via flush-mount DMX ports that were placed next to practical outlets, duplex-style, throughout the precinct set. The bridge connecting each outlet in the duplex was separated, which allowed us to feed the top outlet of the duplex with non-dimmable power and the bottom outlet of the duplex with dimmable power from an ETC Sensor dimming rack. If the flush-mount DMX ports were photographed in a scene, they would appear as if they were a data port of some sort for the precinct and would not look out of place. This gave our talented dimmer board operator, Jeremy Specce, full control of all the multi-parameter properties of the Skypanels. This system allowed us to make on-the-fly intensity or color-temperature changes during rehearsals or while recording without having to keep a technician next to every light to affect the change. For nighttime scenes, we utilized Photoflex HalfDomes with 1K tungsten bulbs. This lent a rich, warm look to the actors. These also were powered by an ETC Sensor dimming rack by plugging directly into the dimmed outlet of any duplex on set.

“In order to augment the soft ambient light that would pour in from the two hallways, we would use Arri T5 Fresnels and 750-watt Lekos as skip bounces on the floor, aimed at white rubber mats that the grip crew would lay out for the lights. We also would cast Leko beams across sets and bounce the light into walls where we couldn’t fit a light. This would give a nice, soft glow to the target area. All aspects of set lighting were patched into the dimmer board, which made any intensity changes, or color temperature, if applicable, a breeze.

“A conference room bordered the third side of the bullpen. Inside the room was a large half-moon window with opaque panes of glass, which was built right up against the fire lane of the stage. In order to create a soft ambiance, Matt Staples mounted a bleached muslin rag on the perimeter stage wall, into which we bounced four Arri T5 Fresnels — also powered by an ETC Sensor dimming rack — that were rigged above the conference room. These were not treated with any gel or diffusion. For direct light, we positioned two Arri T12 Fresnels powered by an ETC Sensor dimming rack from a fixed track to allow us to slide the lights left or right to change the angle of the light pushing through the windows. These lights did not receive any gel treatment either. The bounced Arri T5s were a necessity or else the glass would have appeared to be very dark without it, even though there were T12s punching directly through the window. Glass must have either a diffusion attached to the back side of the pane or a material that bounces an appreciable amount of light back to the glass so that an ambient glow is picked up by the camera to give the window glass presence.

“Opposite the conference room, on the fourth side of the bullpen, were two offices. Each room had four fluorescent fixtures in them, which our shop electrician rewired to accept 2' dimmable Quasar Science T8 3200 LEDs. The bulb manufacturer was able to produce the small amount of 2' bulbs that we required, and we made the decision to use these in the offices because they had a better dimming capability than the fluorescents. Each fixture had its own isolated dimming circuit.”

Collins chimes in: “For night in the precinct, we went with a warmer, more tungsten feel with our lighting. We knocked the levels way back all around, and all the interior lighting on the actors was motivated by the practicals on set. We kept a mix of cool, white, green, and warm practicals in the background and foreground, but the actors were primarily warm tungsten.”

And the cinematographer adds, “One of the funny things we had to deal with was that we didn't have an exterior precinct location established when the set was built. We had to find a way to make the set look like it could ambiguously fit into anywhere between a ground floor to a sixth-floor location. We finally settled on the new Cooper Hewitt Design School in the East Village as our exterior, half way through our first episode!”

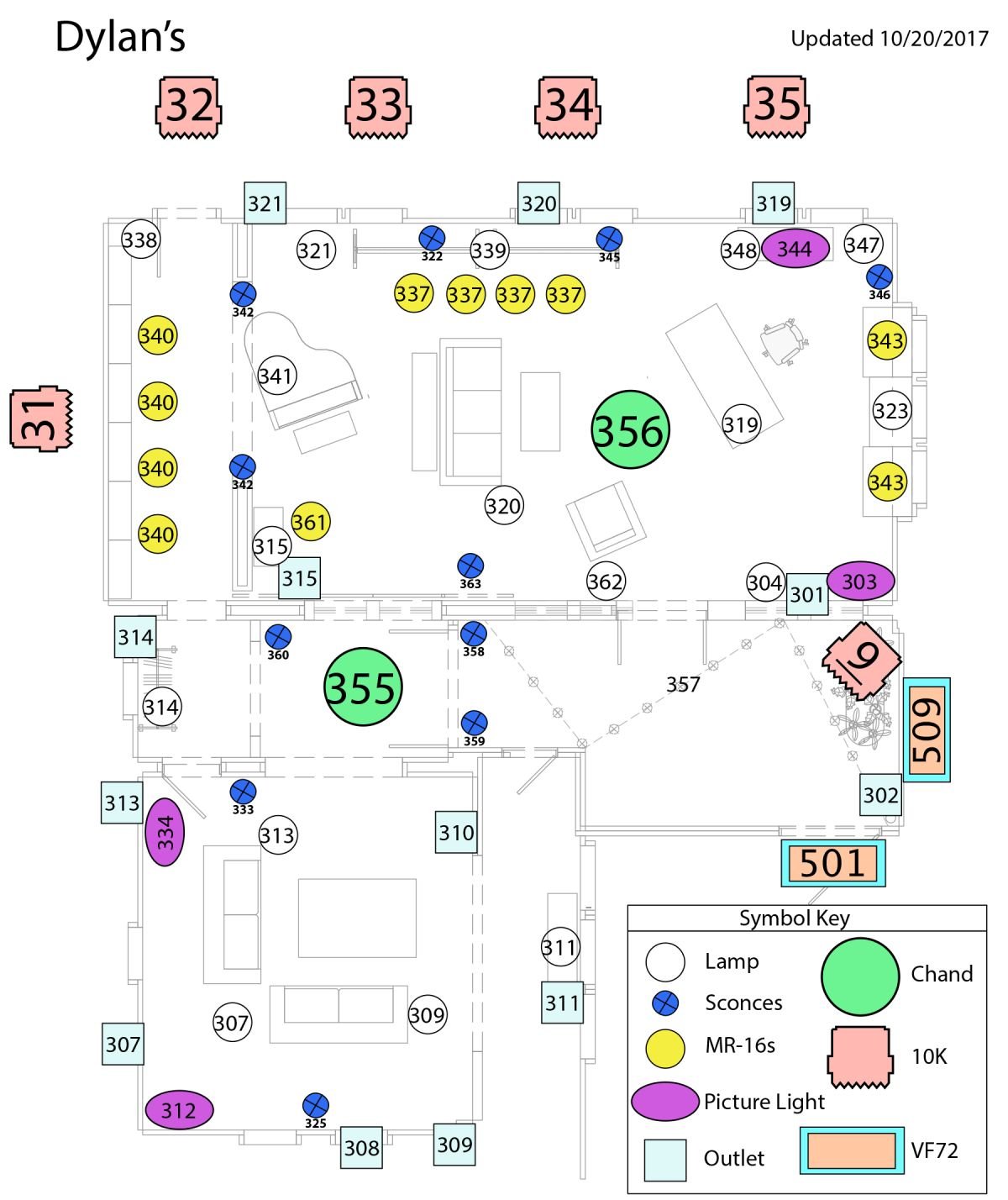

The other new set, depicting Dr. Reinhart’s apartment, actually was established in the pilot episode. For the series, production designer Ray Kluga built an exact replica of the real location interior — a ground-level converted 19th century carriage house — on stage. All windows were considered to be exposed to the sun and street exterior. “Ray installed many beautiful vintage practical lights, lamps, sconces, and chandeliers, which were featured extensively,” says Collins. “We took the approach that, during the daytime, we always were dominated by strong, warm sunlight coming through the windows of the set. We added warm bounce light to lift levels or to wrap the actors faces, but the windows were the dominant source. For nighttime, we used the practical lighting as motivation.”

“A courtyard in the middle of the apartment set employed a similar Ultrabounce to the one in the precinct atrium hallway. We utilized two Studio Force hybrid LEDs and bounced them into the Ultrabounce that was rigged to the pipe grid above the courtyard.

“All other windows in the apartment had curtains and sheers, which again did not require a backdrop. For these windows we pushed around several Arri T12 Fresnels and Arri T5 Fresnels, all powered by an ETC Sensor dimming rack. During night scenes, any Arri Fresnels that illuminated windows — and this goes for every set — were generally operated between 15% to 20% intensity. This gave just a hint of light to the window for the camera to be able to read and also rendered a sodium vapor color quality.”

Adding to the detail, Collins says, “For the nighttime interior, we would use the practical lighting as motivation and would push HalfDomes through diffusion or LiteMat 1 or LiteMat 2 through diffusion for the actors. We also would rig HalfDomes around the set ceiling to give us warm edge light or backlight. Occasionally, we'd bounce a Source 4 Leko into a Booklight of unbleached muslin and full-grid diffusion. This was a beautiful set but a little dark in places, and Ray added some practicals after our first time shooting there to pull it all together. The patio needed to feel as if sun could reach in, so we rigged a T12 and positioned it based on where the camera was looking. At night, we had a string of Edison bulbs motivating the exterior patio lighting.”

Overall visually, the creators wanted New York to feel somewhat surreal. “It was an elevated sense of reality, if you will,” Collins notes. “We saturated the color so that everything had a pop to it.”

Colorist John Crowley at Technicolor-PostWorks NY handled the color grading through Filmlight's Baselight system, performing the finish in 1920 x 1080 resolution 23.98fps ProRes 444 Log with a final output format of 1080i 59.94fps XDCAM MXF for television delivery. Effects house The Molecule in New York performed the visual-effects work with the 8K- and 6K-originated material, and the effects artists were very appreciative of the extra resolution to work with.

In addition, Crowley added a grain effect to the finished images, which “added a really nice layer to the visuals,” says Collins.

“This was a great learning curve to be able to shoot in 8K with 70mm primes,” adds the cinematographer. “It was a great new way to see things, and it allowed CBS and the creatives the most freedom to tell the story. I would love to shoot everything in this format going forward!”