Jack Cardiff, BSC: An Eye for Color

“I’ve learned, seen and experienced so much. But you know how it is. You are always looking out for the next thing.”

Editor's note: This article was originally published in March of 1994 as Cardiff was honored with the ASC International Award.

Once asked to name the best color movie ever made, Natalie Kalmus, the daughter and protege of Technicolor inventor/founder Dr. Herbert Kalmus and Technicolor consultant on a number of classic films, offered her choice without a moment's hesitation: 1948's The Red Shoes, written and directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. Based on a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, the story concerned an obsessive ballerina and her trying personal relationships. If you've seen it, chances are that you still have vivid memories of the magical ballet sequence featuring Moira Shearer.

But not everyone agrees with Natalie Kalmus. Many aficionados believe Black Narcissus is the best Technicolor film ever made. This 1946 film, also directed by Powell and Pressburger, focused on five nuns and their struggle to overcome great odds while building an orphanage in a mythical mountain setting. Black Narcissus earned critical acclaim in many categories. The critics lauded the camerawork with comments such as "Dazzling colors, rich pastels... never garish."

Both films were photographed by Jack Cardiff, BSC, who won an Academy Award for Black Narcissus. At the time, Cardiff already had some 30 years of experience, but the two pictures were just his second and third assignments as a director of photography. Prior to his career in feature-film cinematography, he had been a child star, camera assistant and operator, as well as a Technicolor consultant and travelogue cinematographer extraordinaire.

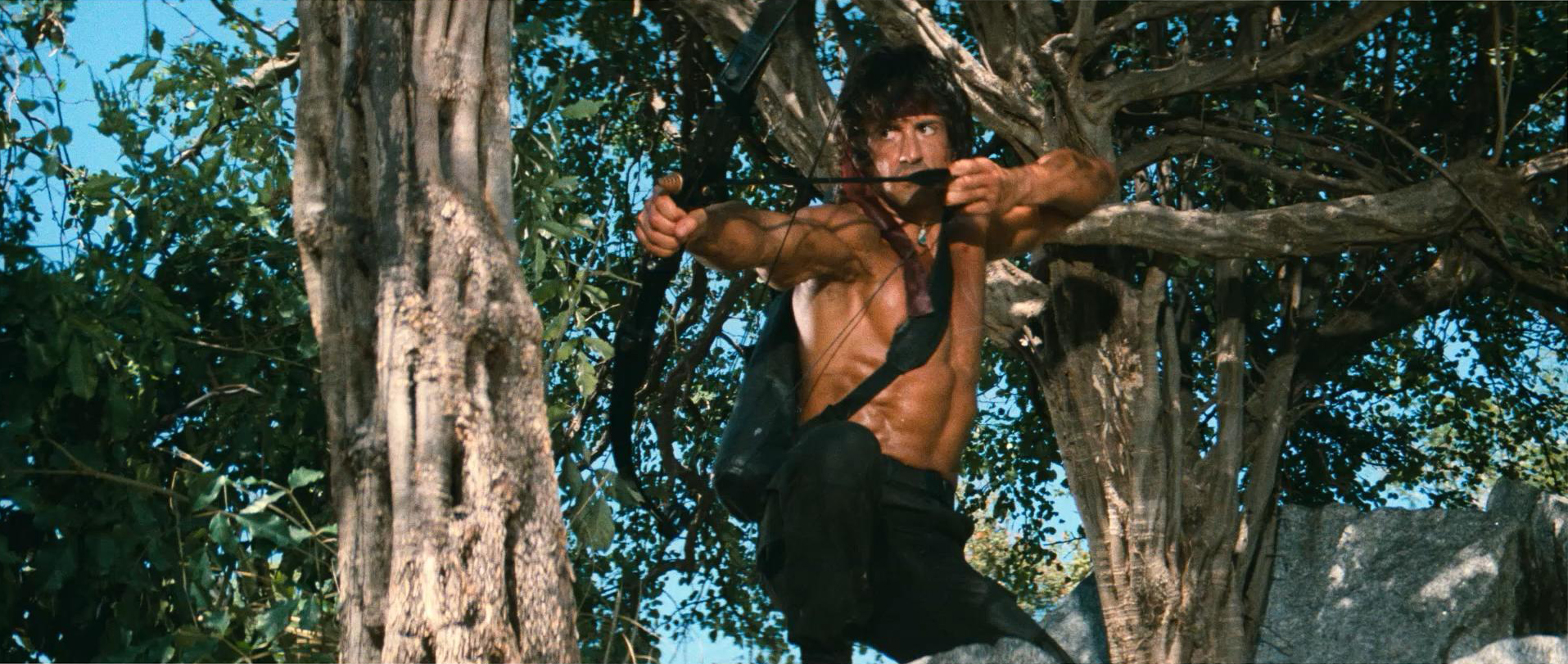

Cardiff collected subsequent Oscar nominations for War and Peace and Fanny. His eclectic body of work also includes such unforgettable films as The African Queen, The Prince and the Pauper, Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, and The Barefoot Contessa, as well as the contemporary adventure films Rambo: First Blood Part II, The Vikings, and Conan the Destroyer.

In mid-career, Cardiff tried his hand at directing, and became the only filmmaker to earn Oscar nominations for both directing and cinematography: in 1960, he received the Golden Globe and New York Film Critics awards, along with an Oscar nomination, for directing Sons and Lovers. Freddie Francis, BSC, also won an Oscar for his cinematography on the film.

Cardiff was born in Yarmouth, England in 1914, to parents who performed in vaudeville and occasionally acted in the nascent entertainment form of motion pictures. At age four, Cardiff made his first on-screen appearance in a film called My Son, My Son.

The young thespian went on to star in Billy Rose and The Card, and performed at different times with Dorothy Gish, Will Rogers, Pola Negri, Adolphe Menjou and Violet Hobson. By the time he turned 11, however, the acting assignments were getting further apart; Cardiff was becoming too old to continue as a child star. His last performance was in Tiptoes (1927). In 1928 he got a job as tea boy and runner at British International Studios in Elstree.

One day, during a shoot, German cinematographer Werner Brandes shouted "Hey you!" to the 14-year-old Cardiff, and told him to rotate the lens from one pencil mark to another when he gave the word. Later, when Cardiff asked what he had done, Brandes replied, "You followed focus, sonny."

Cardiff's interest in the camera grew. His next job was working as a clapper boy with various cinematographers, including Claude Friese-Green, whose father, William, had invented and patented one of the first motion sequence cameras in 1889. Only 30 years after that historic invention, Cardiff was getting his own career underway.

Cardiff recalls that operating the hand-cranked machines took more than a rock-steady hand and the ability to turn the crank at a consistent 16 frames per second; one also needed a sense of drama and flawless eye-hand coordination.

Cardiff collaborated with some extraordinary filmmakers who were defining the emerging art form. "I was working in the special effects department with Alex Korda's company at Denham Studios," Cardiff recalls. "Hal Rosen [ASC] had come over from the States, and the studio manager asked if I wanted to operate for him. Hal was firing a lot of operators, so I said no. But finally, I was the only one left, and I accepted the job."

In 1937, while Cardiff was operating for another famous Hollywood cinematographer, Harry Stradling, ASC, on Knight Without Armour (starring Robert Donat and Marlene Dietrich), he was asked to interview for a job that would take him to Hollywood to learn about a new color system called Technicolor.

A half-dozen or so operators were being interviewed. Several of them had already been quizzed, and they warned Cardiff that the questions were very technical and difficult. He didn't have high hopes, but the questions proved to be even worse than Cardiff had anticipated. The interviewers asked where he had attended film school, and probed him with technical questions about polarizing light and the qualities of different camera negatives.

Cardiff told his inquisitors that they were wasting their time talking to him. There was a shocked silence, after which someone asked him how he hoped to become a cinematographer.

"I told them I studied the works of painters [like] Vermeer, the Old Masters and the Impressionists," he says. "I could also describe and match how the light fell in a subway, in my house, or on the street at night. They asked a few questions about lighting, and then someone inquired about a face in a Rembrandt painting. I said the light was on the right side of the face."

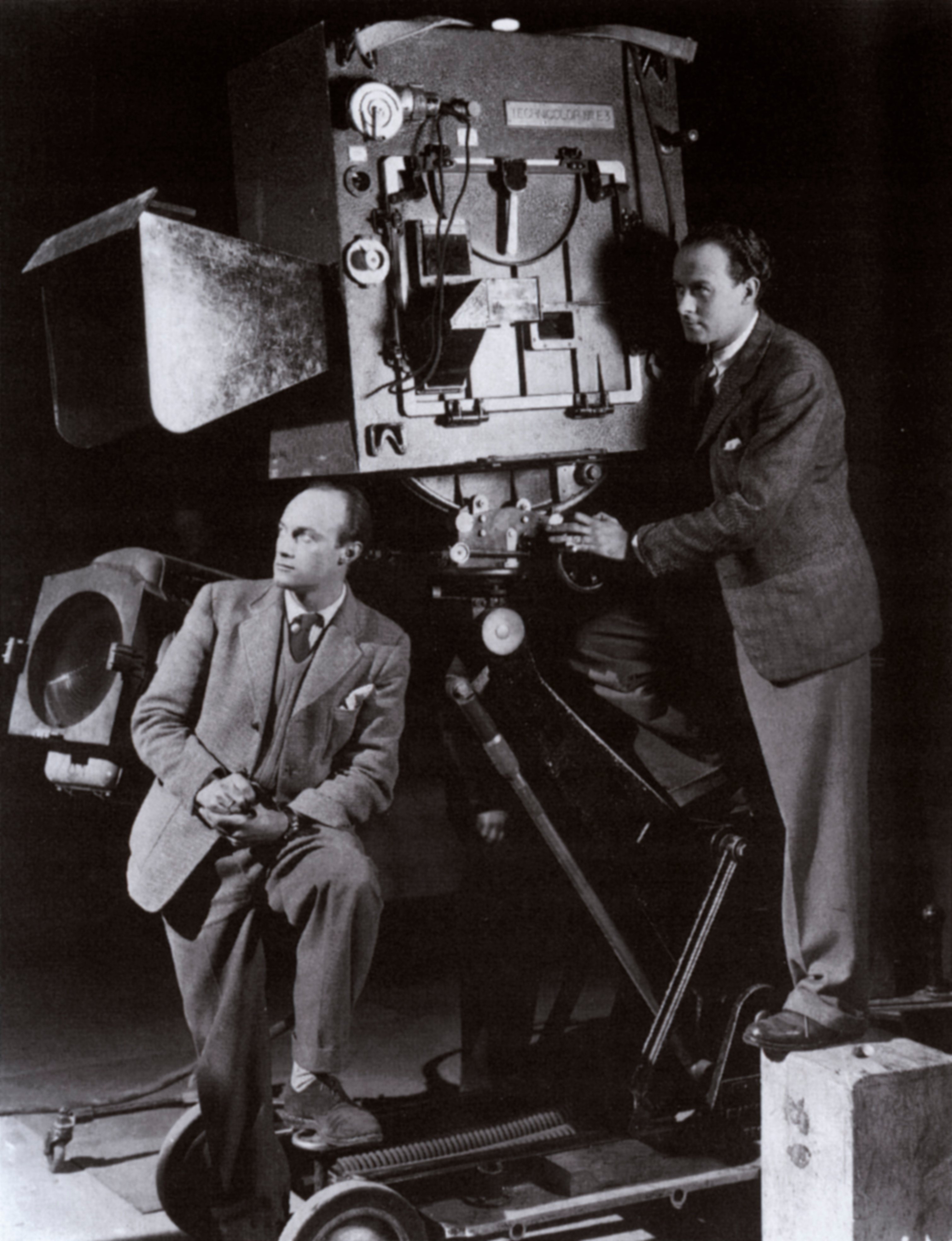

Cardiff got the job. He always suspected that he was chosen because he admitted that he had a lot to learn about photography. Instead of being sent to Hollywood, he was put to work as an operator with Ray Rennehan, ASC, one of the most renowned masters of the Technicolor process, on a picture he was shooting at Denham Studios called Wings of the Morning. It featured Henry Fonda and Annabella.

Afterward, Cardiff worked for Technicolor in London, where the company had built a lab and were installing and testing equipment. Cardiff shot a half-dozen theatrical commercials which provided an opportunity for him to experiment. Subsequently, a five-year series of Technicolor theatrical travelogues called World Window took him to every corner of the world through 1942.

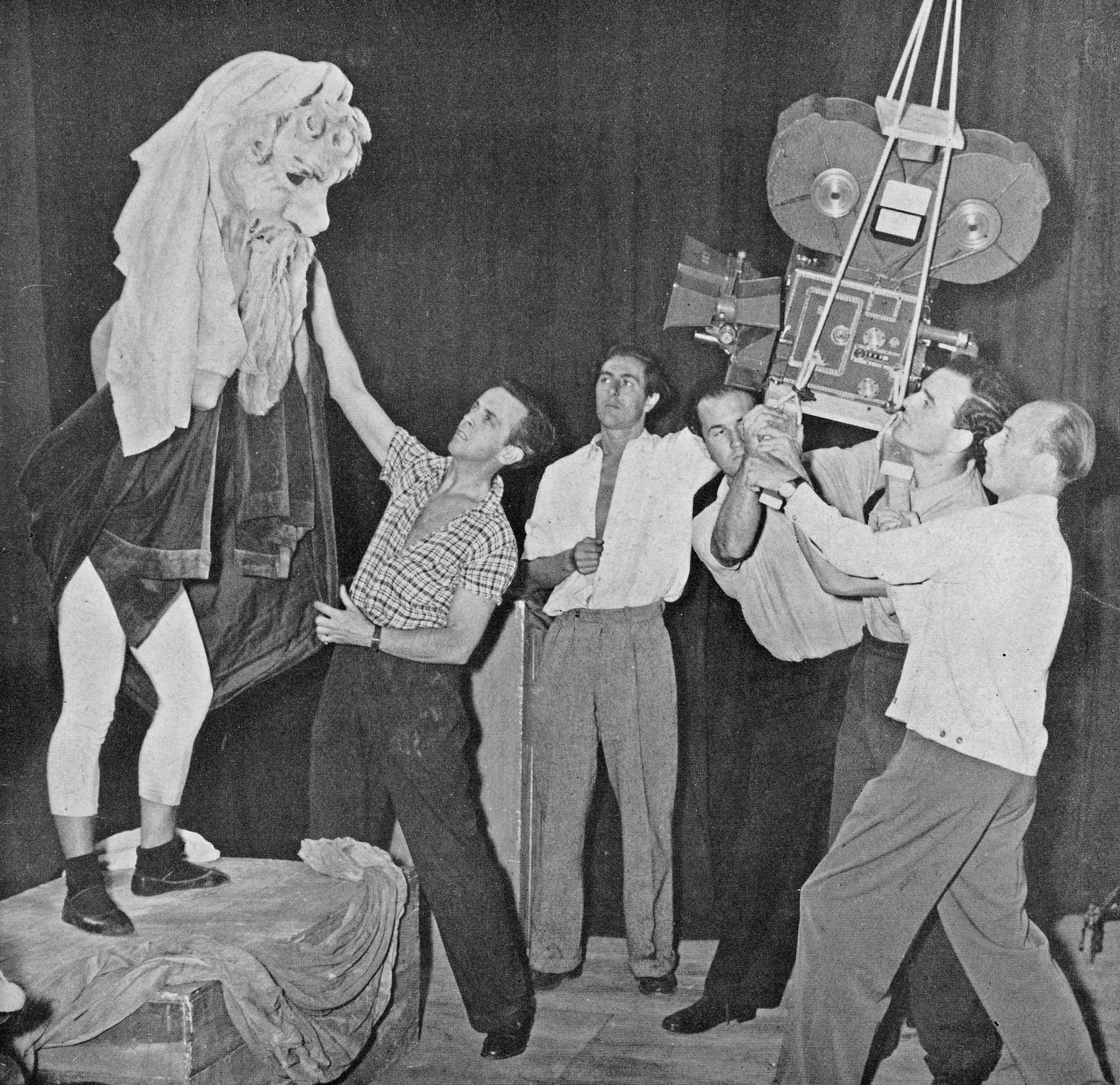

"There were only four Technicolor cameras in the country, and they were very valuable," Cardiff says. "Every night the assistant took the camera to his bedroom so he could keep an eye on it. Every three days he disassembled it, took out the prism, and checked the alignment. There were two gates and three film strips, and tolerances had to be within 8/10,000ths of an inch."

There were some great adventures along the way. Cardiff recalls shooting at the top of Mt. Vesuvius during a volcanic eruption. It took 40 local guides to haul all of the camera equipment to the top of the mountain. "We shot all day. There was burning lava all around us," he says. "It burned the tripod and our shoes. One of the crew ended up in the hospital. But the film was magnificent."

In 1942, he started work on a two-year documentary film project, a tribute to the British Merchant Navy. Cardiff sailed with a convoy from London to New York, and then back again. The film was authentic in every way; in fact, four ships were sunk by U-boats in one attack on a convoy. Cardiff spent six months shooting film in a lifeboat to show the audience what that experience was like. The film was called Western Approaches in England, and The Raiders in the United States.

Cardiff's first experience as a feature-film cinematographer was a 1943 Technicolor film called The Great Mr. Handel, on which he shared duties with Claude Friese-Green. Cardiff served as Technicolor consultant, but he also shot half of the film under Friese-Green's watchful eye.

Immediately after World War II, Cardiff shot second-unit on The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (another Michael Powell/Emeric Pressburger film) and Caesar and Cleopatra. The assignments were miserable experiences for Cardiff, who felt that the first units were having all the fun. But there were moments of serendipity. One day while shooting Colonel Blimp, he was lining up a difficult shot of a dozen stuffed animal heads on a wall. Cardiff was so busy lighting that he didn't notice that director Powell was scrutinizing his every move. He asked Cardiff if he wanted to shoot his next film, and promised to call within a year. True to his word, Powell later called Cardiff in Egypt, where he was shooting second-unit for Caesar and Cleopatra. He invited him to shoot A Matter of Life and Death, which was renamed A Stairway to Heaven in the United States. The picture marked the beginning of his cinematic collaboration with Powell and Pressburger, who co-authored scripts and collaborated on directing.

The next year, Cardiff filmed Black Narcissus, partially on location in the Far East. One day during production, Powell asked Cardiff if he liked ballet. The director was shocked when Cardiff expressed disinterest. Powell informed him that his next job would be on a ballet film called The Red Shoes. He advised Cardiff to learn about ballet by attending performances at Covent Garden. Upon his return to London, Cardiff watched several shows a week for many months, and spent considerable time backstage during rehearsals, soaking up the ambiance.

"All of us felt that we were working on a classic when we filmed The Red Shoes," Cardiff says. "I was a great fan [of ballet] by then. Moira Shearer and the other ballet performers and actors were totally engaged in the story. Michael [Powell] was like a symphony orchestra conductor, drawing every ounce of creative talent from everyone."

Cardiff exploited the use of color for the Technicolor assignment. He photographed the fantasy ballet sequences with diffused lighting and filters on the lenses to create a dreamlike quality and contrasted that approach by filming real-life scenes in deeply saturated, luminous reddish colors.

"We shot some tests, and got to use a few of those ideas in the film," Cardiff recalls. "There are sequences with people jumping from heights in slow-motion that we filmed with a wide-angle lens. There's one shot where a dancer is twisting in mid-air. He appears to float as light as a piece of falling paper."

Every movement was precisely choreographed with music, which had been recorded first. To capture the leaping dancer, Cardiff altered the frame rate from 24 images a second to 96, and then back to 24. The actual leap happened in a mere two-second span, but it seems to last for an eternity, a tricky feat given Technicolor's slow lenses and cumbersome cameras. "The lenses were actually very good, but the Technicolor film was slow," Cardiff notes. "I remember that we were shooting at f1.5, and we must have had 650 footcandles coming from those big arc lights."

After all of the work, the British public wasn't ready for The Red Shoes. It opened in London to mixed reviews and with no publicity. "Fortunately, a distributor from the United States saw it with his family, and they loved it," Cardiff recalls. "He brought it to the Bijou Theatre in New York, where it played for two years. Years after it opened, we were told we were right. It was a classic film."

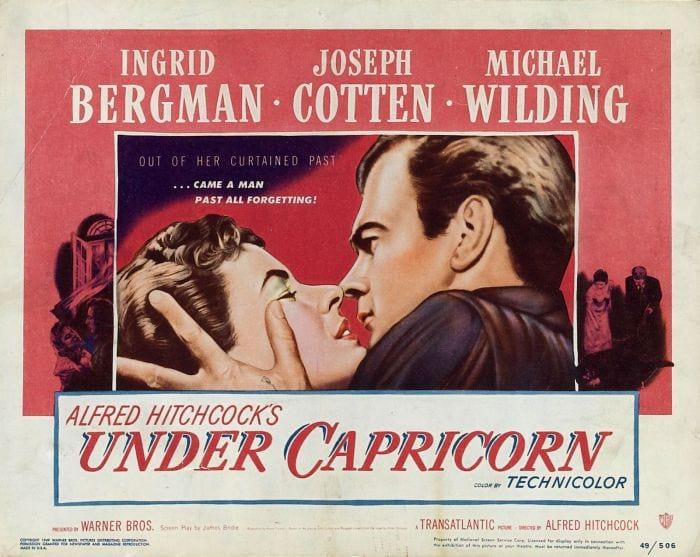

In 1949, Cardiff photographed Under Capricorn for Alfred Hitchcock. "The first time I worked with Hitchcock, I was still a clapper boy," he says. "We used a very mobile camera. There were 10-minute-long shots with no cuts or changes of camera angle. That was very novel in those days. We would start a scene in the kitchen, move through a hallway into a drawing-room, go back into the hallway, up the stairs, and down a passageway to a bedroom, where we photographed Ingrid Bergman. Then we turned around and retraced our steps. There was dialogue every step of the way."

Practically every scene consisted of long, moving shots. The idea was to involve the audience in the picture more as eavesdropping participants than as spectators. "There were exceptions, but they weren't any easier to shoot," Cardiff recalls. "There was one shorter, isolated shot where we had the cast seated around a long Georgian table. There were four or five people on each side. Ingrid Bergman was seated at the head of the table. Hitchcock wanted a long tracking shot ending with a close-up on her face. He wanted a low angle, but we had a big blimp on the camera to muffle sound, and that made it difficult. We took the long shot, and then as we moved in tighter, the table was actually cut into six, seven or eight sections. As we moved past the actors on either side, they fell away backward onto mattresses. We came right down the middle of the table into a close-up."

It was an extraordinary way to shoot a film in those days. Cameras were unwieldy, film stocks were slow, and there was no reflex viewing. "No one would call it beautiful photography," says Cardiff, "but the operator did a wonderful job. I thought he deserved an Oscar, but that's not the way it's done."

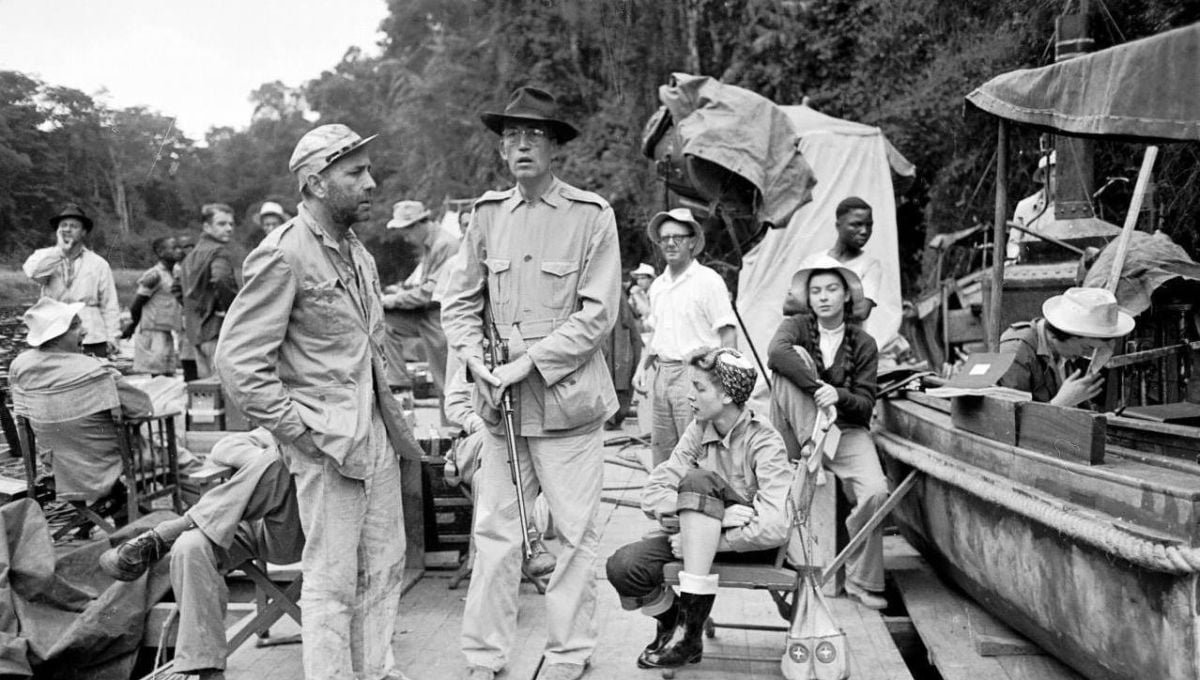

Under Capricorn was followed by such films as The Black Rose, starring Orson Welles and Tyrone Power, and Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, starring Ava Gardner and James Mason. During that period, Cardiff worked with numerous other actors and actresses who have subsequently become legendary characters in film lore, but the film that everyone asks Cardiff about is The African Queen. Filmed in 1951 in what was then the Belgian Congo, the picture is still popular today on television and home video. Chances are that well over a billion people have seen Katharine Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart play out their love story against the background of a World War I struggle between two colonial powers, Germany and England.

The film's director, John Huston, co-authored the script with James Agee. The images that filmgoers most often recall are the vivid and stunningly realistic African backgrounds, and the faces of Hepburn and Bogart. What Cardiff remembers was that everything that could go wrong, did.

"We planned to shoot the film in British territory at Lake Victoria, which is about 3,000 feet above sea level," Cardiff remembers. "It was beautiful. It was almost like being on a holiday. But Huston went on a location scouting trip and sent a cable saying he didn't like the location. It was too pretty. A couple of weeks later, there was another cable, saying he had found the perfect location in the Belgian Congo. It was a two-mile jeep ride through a savage jungle. The water was absolutely black. We were supposed to sleep in tents in a jungle that was filled with poisonous snakes."

The cast and crew crowded onto a houseboat, and everyone except Huston and Bogart got sick. Cardiff recalls that doctor after doctor attempted to keep the cast and crew healthy enough to work. "Once we had to stop production for a week," he says. "I had a 104- or 105-degree temperature, and I wasn't the only one. The doctor said we had to rest and eat better. The company brought in about 50 sheep from Nairobi. When we woke up the next morning, crocodiles had eaten them."

About a week before production wrapped, a new doctor finally discovered the cause of the illnesses. The cast and crew were supposedly drinking "filtered" water pumped onto the houseboat from the river, but there were no filters in the pump; someone had removed them. Huston and Bogart were unaffected, Cardiff explains, because they were drinking something stronger than water.

"Years later, I met Steven Spielberg, and he told me that he had always wanted to meet the cameraman who shot The African Queen,” Cardiff says. "It was a wonderful story with a great director, and the casting was right. But I was never particularly proud of the cinematography. Everyone was ill, and we did a lot of shooting from a small boat. But that's the way it goes. If the picture is a success, everyone likes the photography."

There were many other memorable films, too numerable to describe in great detail. It was fitting that Cardiff filmed The Magic Box in 1952, commemorating the 60th anniversary of cinematography and the special contributions of William Friese Green. Cardiff went on to shoot The Barefoot Contessa, starring Ava Gardner, in Rome with director Joseph Mankiewicz; the picture drew large audiences and earned kudos for Cardiff. He also traveled to Mexico to photograph The Brave One, which marked the return of blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo.

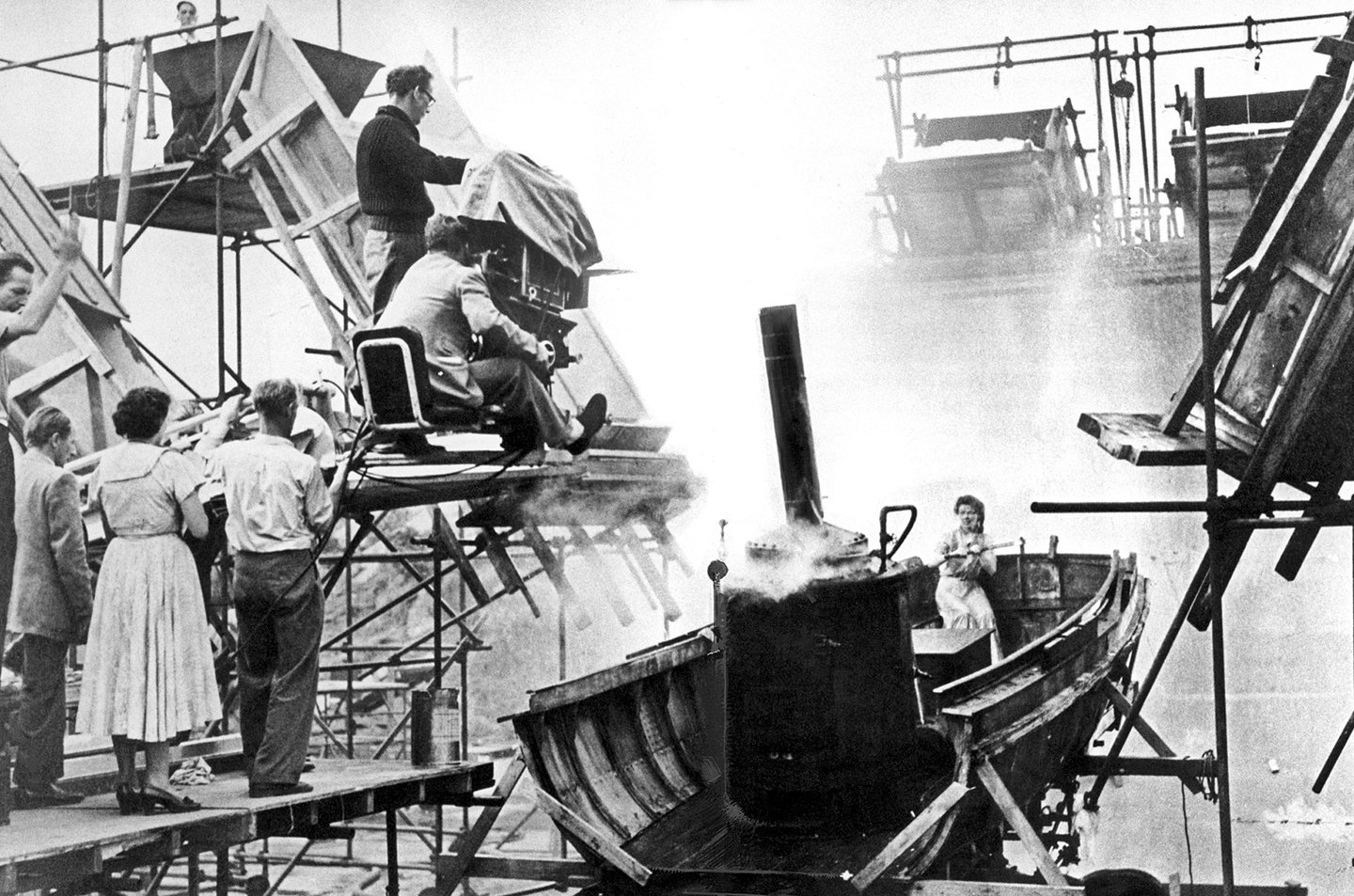

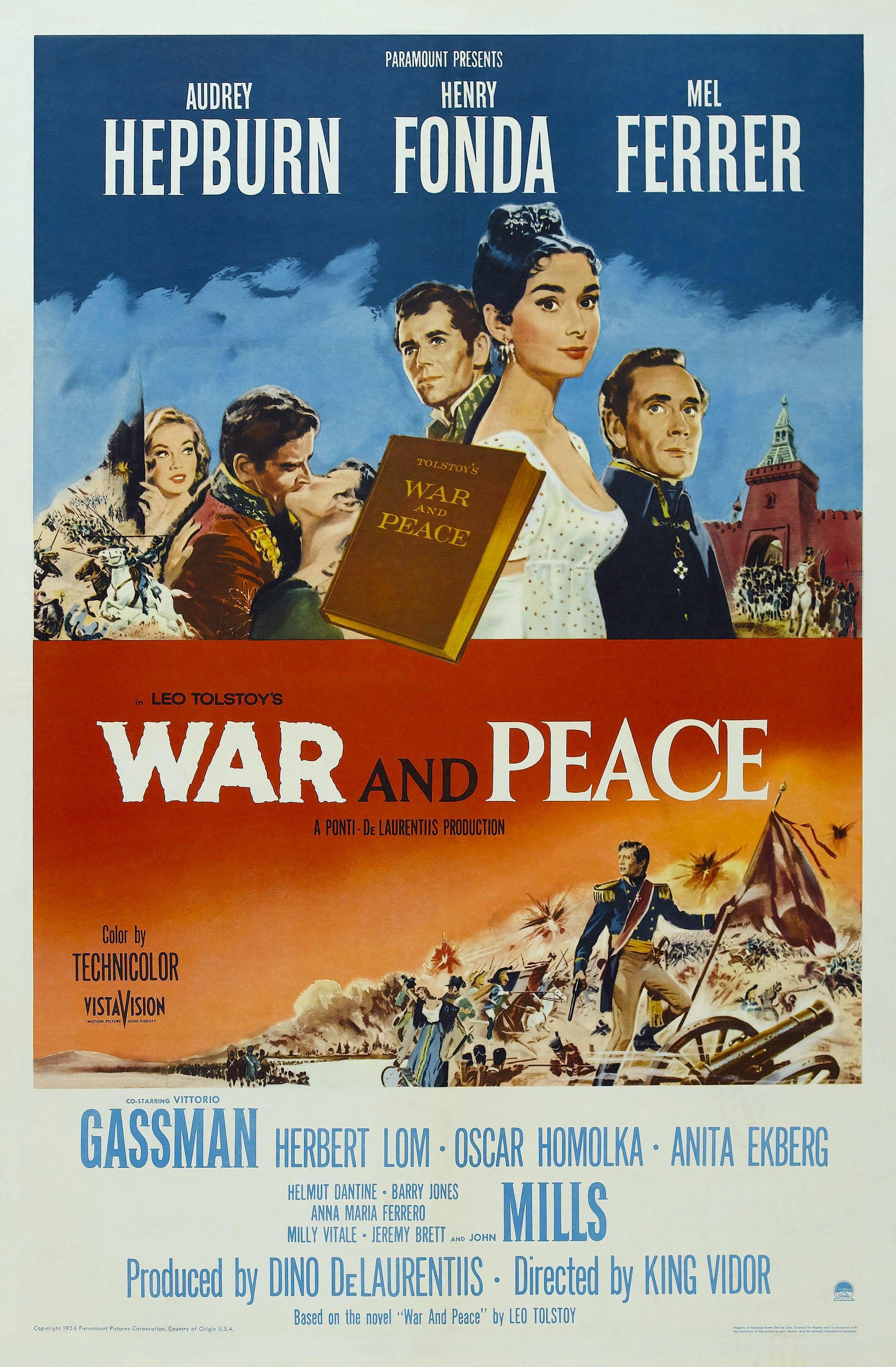

Ask him to choose his favorite from his body of work, and Cardiff will probably name War and Peace, an epic based on the Tolstoy novel. Filmed at locations in Yugoslavia and Italy, it was produced by Dino de Laurentiis and directed by King Vidor, with a cast that included Henry Fonda, Audrey Hepburn and Mel Ferrer.

Vidor and Cardiff employed fluid camera movement and ingenious staging throughout the film. The hopelessness of Napoleon's retreat is conveyed through extreme high-angle coverage; a white mist lifts to reveal the true proportions of disastrous battle at a riverbank. Cardiff earned his second Oscar nomination for War and Peace. (Henry Hathaway and John Wayne were so certain Cardiff would win that they organized a celebration dinner the night before the Academy Awards, but the award went to Around the World in 80 Days.)

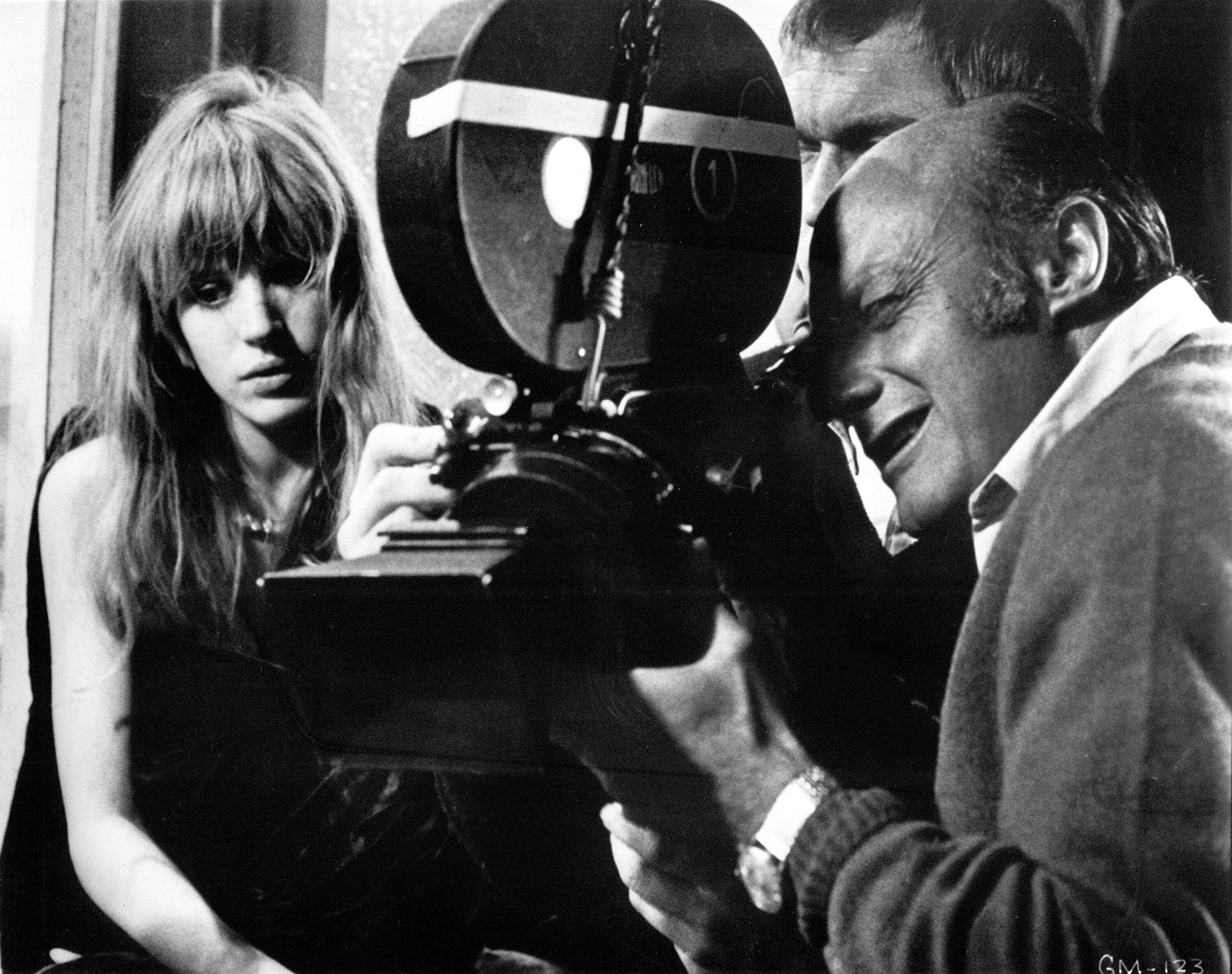

In 1958, 20th Century Fox gave Cardiff the opportunity to film a low-budget mystery thriller called Intent to Kill, and in 1960 he directed The Scent of Mystery, a gimmick film that depended heavily on tell-tale odors that were let loose into theaters. That adventurous nature paid great dividends later in 1960, when he reached the pinnacle of his ability as a director with Sons and Lovers, a movie adapted from a D.H. Lawrence novel that starred Dean Stockwell and Trevor Howard.

Cardiff returned to cinematography for Fanny — director Joshua Logan’s 1961 adaptation of his musical, starring Leslie Caron, Maurice Chevalier and Charles Boyer — but he continued directing during the 1960s and early '70s, compiling a notable list of credits that included My Geisha, The Girl on a Motorcycle and Young Cassidy. During the 1980s, he continued his work as a cinematographer with Death on the Nile, The Awakening and The Dogs of War.

His appetite for exploring new concepts led him into shooting two Showscan films, Call From Space and The Magic Balloon, during the late 1980s. The projects marked the first use of the CP65 camera, now more typically called the Showscan camera. Up until that point, there was some skepticism about whether large formats like Showscan could be used for narrative storytelling. With a smile, Cardiff notes that the two short (25- and 45-minute) films were a piece of cake compared to his experience shooting Technicolor movies.

He averaged 15 setups a day. "The pace was about the same as it would be on a 35mm film," he says. "There were no limits imposed by the format. The camera is mobile, and it gave me a broad range of 65mm lenses from 28mm to 600mm. We were shooting with the Eastman EXR 5296 500-speed film, which was new at that point. It gave me the latitude to pull deep stops."

Having such options is a luxury for Cardiff. Back during the late 1930s, when he was shooting Technicolor travelogues for World Window, the company got permission to shoot in St. Peter's Cathedral, which had never been done before. Cardiff was limited to the use of five 2K lights. The Technicolor film in those days was painfully slow, but Cardiff came up with a solution: moving back as far as he could, he exposed 10 feet of film, rewound it, and exposed it again, repeating the process eight times. Then he shot the next 10 feet. "In effect, I was shooting a one-second exposure on each frame," he says. "I did it by instinct, and it all worked out perfectly. We got beautiful footage."

What's next for Cardiff? "I've learned, seen and experienced so much," he says. "It's been a long journey, and I'm writing a book about it. But you know how it is. You are always looking out for the next thing."

Cardiff's autobiography, Magic Hour: A Life in Movies, was published in 1997.

He died on April 22, 2009.

The cinematographer was also the subject of the exemplary documentary Cameraman: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff (2010), directed by Craig McCall: