Fly Girl: Jackie Brown

Quentin Tarantino and Guillermo Navarro exploit Los Angeles locations in a jazzy tale of jive-talkin’ double-crossers.

Unit photography by Darren Michaels

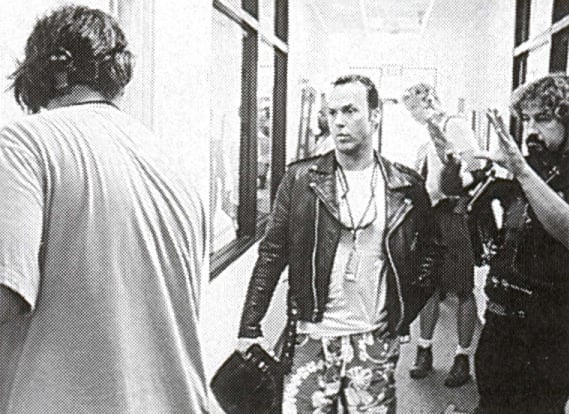

Hollywood partnerships sometimes come about in odd ways. Before shooting Quentin Tarantino’s new film, Jackie Brown, Mexican cinematographer Guillermo Navarro knew the writer/director primarily as an actor. The cameraman first met Tarantino in his native land while shooting filmmaker Robert Rodriguez’s high-octane action film Desperado, in which the ever-hip auteur makes a cameo as a gringo jokester who is blown away by a humorless Mexican gangster. The next time Navarro saw Tarantino on a set, the latter was once again hamming it up for the cameras in a self-parodying role for the anthology film Four Rooms; after completing Rodriguez’ segment, Navarro shot a few scenes for Tarantino’s episode. On both films, Tarantino was able to observe the director of photography’s working methods firsthand. After the duo crossed paths yet again — on Rodriguez’ vampire road flick From Dusk ’Till Dawn (written by and starring Tarantino, the consummate multi-hyphenate) — the filmmaker decided that Navarro would be his ideal collaborator for Jackie Brown.

“I wanted Jackie Brown to have richness and depth, but I wanted it to look more ‘real.’”

— Quentin Tarantino

Outlining the visual strategy for this new film, Tarantino offers, “As far as the look was concerned, I wanted the entire production to be very down-and-dirty, almost in the same style as Reservoir Dogs [photographed by Andrzej Sekula]. I wanted Jackie Brown to have richness and depth, but I wanted it to look more ‘real.’ My other films do look very ‘real,’ but at the same time there’s a ‘splashy-movie’ quality to them. I just wanted to be able to move on the run, and I knew Guillermo could do that.”

To give his crew a basis — but not a blueprint — for this gritty, realistic look, Tarantino screened Ulu Grosbard’s 1977 crime film Straight Time (shot by Owen Roizman, ASC). The director says that he admires the film’s raw vision of L.A., as well as its blending of location and studio work with a cinematographic style that mimics an available light ambiance. Tarantino and Navarro also watched Robert Culp’s 1972 action melodrama Hickey and Boggs (photographed by Bill Butler, ASC) and Peter Bogdanovich’s 1981 farce They All Laughed (Robby Muller, BVK, NSC). The director felt that each of these films made interesting and realistic use of the metropolitan landscapes of L.A. and New York, respectively.

Tarantino also selected Navarro because of the cinematographer’s non-possessive attitude toward the camera. “Since I wasn’t acting in this movie, I wanted to do more hands-on camera operating than I’d done before,” admits Tarantino. “I knew from Guillermo’s work with Robert that he wouldn’t have a problem with that. Actually, he became very much like a teacher, and we had a terrific operator, Dan Kneece, who was totally on-board as well: after I would operate a shot, both of them would say to me, ‘Now, you want to remember to keep his face in this kind of frame.’ Their input made it a really wonderful experience.”

“The fact that this was a contemporary story had a lot to do with how I approached the style. Anything seen in everyday life is absent of the ‘magic’ of style due to one’s daily relationship to it.”

— cinematographer Guillermo Navarro

In adapting Elmore Leonard’s crime thriller Rum Punch (released in 1992), Tarantino transplanted the book’s narrative from Miami’s South Beach to L.A.’s South Bay, an area which encompasses the towns of Torrance, Hawthorne, Carson, Wilmington, Long Beach, San Pedro, Palos Verdes, Inglewood and Marina Del Rey. The only South Bay site Tarantino had previously utilized on film was the Hawthorne Grill, the eatery which bookends Pulp Fiction. Explains Tarantino, “I don’t know anything about Florida, and didn’t really look forward to shooting the movie there. Having grown up in the South Bay, I know it really well — from the affluent areas to the seedier areas. I definitely felt that I could bring [that knowledge] to the material to make it mine. Besides, people shoot in Florida all the time — nobody shoots in the South Bay.”

Given his familiarity with the area, Tarantino penned the script specifically for locations that he scouted on his own during the writing process. He says, “If you’re writing about an area in Los Angeles from memory, and your memory goes back more than a year or year-and-a-half, you can make big mistakes, because L.A. is so transient: you can live in the place for 15 years, but if you leave and go back two years later, the Arby’s that was there forever is gone, and an El Polio Loco is in its place. The entire movie pretty much takes place within 20 minutes of the airport, except for one section set in Hollywood, and another in downtown L.A. This works very organically since Jackie is a stewardess who lives in Hawthorne, which is right next to LAX [Los Angeles International Airport].”

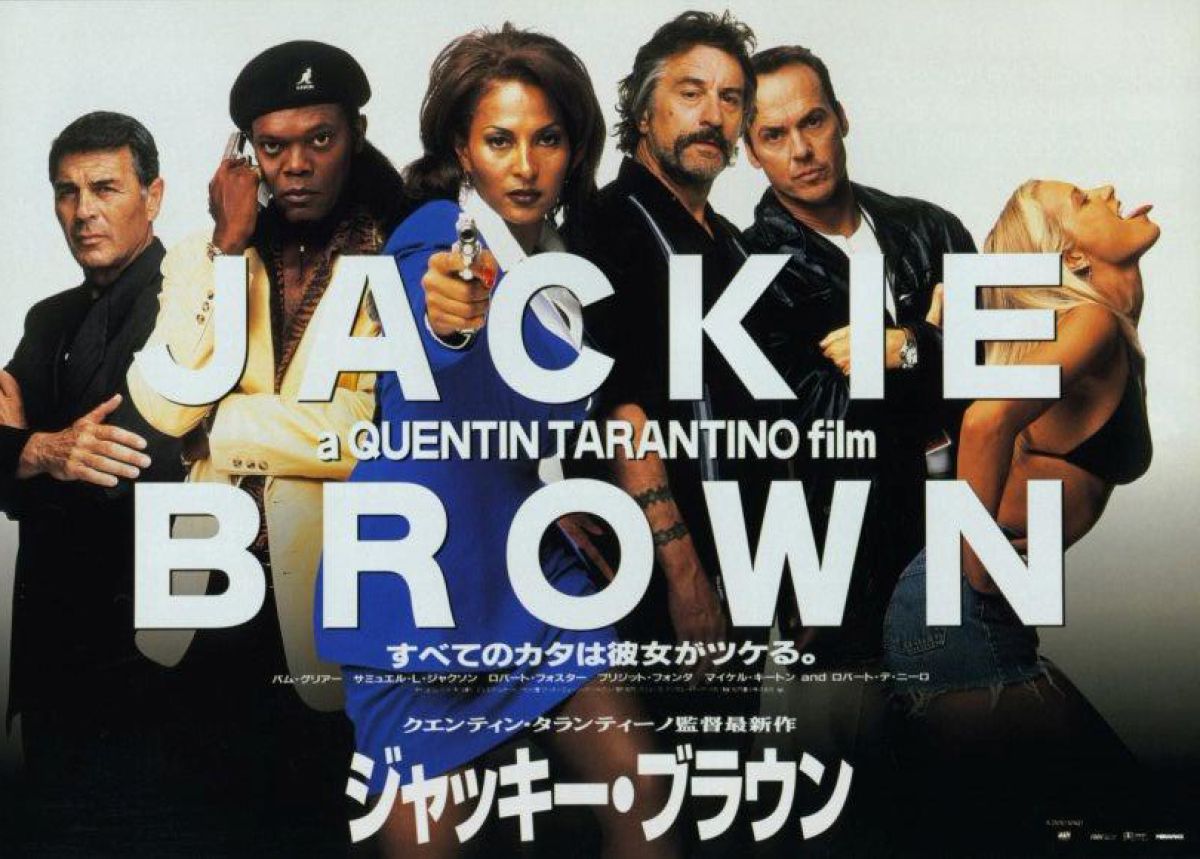

As the film begins, stewardess Jackie Brown (Pam Grier, star of such cult 1970s “blaxploitation” films as Coffy and Foxy Brown) is trying to make ends meet as an employee of the Mexican charter company Cabo Air. To compensate for her paltry paycheck, Jackie occasionally facilitates international transactions for Ordell Robbie (Sam Jackson), a shiftless gun-runner and new-jack-of-all-trades. When not running scams, Robbie hangs out with his somewhat awkward criminal associate Louis Gara (Robert De Niro) — recently released from prison after serving a robbery sentence — and his ditzy, dope-smoking moll Melanie Ralston (Bridget Fonda). After being caught with $50,000 in cash and a small packet of cocaine on her person, Jackie is forced to take part in a complex sting operation concocted by federal agent Ray Nicolet (Michael Keaton) to bring Robbie down.

Given Tarantino’s affinity for discourse, Navarro found his greatest challenge on Jackie Brown to be devising a unique style for a dialogue-driven film set in some not-so picturesque locales. Offers Navarro, “The fact that this was a contemporary story had a lot to do with how I approached the style. Anything seen in everyday life is absent of the ‘magic’ of style due to one’s daily relationship to it. Interpretation is an ingredient one can sculpt with when addressing the future or the past, but not when dealing with a contemporary story that has strong doses of realism. This entire film takes place at locations everyone has a visual relationship to — such as a mall and an airport. There’s no interpretation that can cross the everyday vision of these places, so I had to take a very realistic approach. But being on location can be very difficult because stuck with the space. Since the story is very dialogue-driven, it became complicated to execute some of the shots [in a visually interesting way).”

The widescreen compositions in Tarantino’s directorial debut, Reservoir Dogs, were dictated more or less by a scene’s action; much like the subjective observations of a roving eye, the heist film’s involving camerawork often veers into a kinetic, handheld style. In contrast, Pulp Fiction (again, shot by Sekula) plays out mainly in proscenium-style frames; handheld maneuvers are seen only during crises like the Hawthorne Grill robbery, and Steadicam shots (such as the initial survey of the nostalgic Jack Rabbit Slim’s eatery) are equally scarce.

The camera motion in the 2½-hour Jackie Brown — which Navarro shot with Moviecam Compacts in the spherical 1.85:1 aspect ratio — combines both of these styles. The first 90 minutes of this character-driven picture establish the plot primarily through exposition sequences that allowed the cameraman to indulge in “portrait photography” which treats the faces of various characters as landscapes in and of themselves. Tarantino dubs such shots “Sergio Leone close-ups,” which basically consist of “tight close-ups in which the top of the frame ends on the actors’ foreheads and the bottom of the frame ends on the bottom of their chins.” He adds, “It’s a very strong choice to shoot them like that since we used actors who have cool-looking faces. This cuts together well, especially in certain dialogue scenes, because their faces hold the screen.”

Navarro adds “The framing depended upon the state of the conversation, or how much interaction there was [between the scene’s principals]. We did do a lot of side close-ups, but not just close-ups where someone is almost talking to the camera just off the lens; we did a lot of shots that had more separation: the close-up is a profile, and there’s no relationship with the eye-line of the person who is being spoken to. Many times, we let the scene go into a two-shot because the shot was about that interaction. That type of framing allows another scene to be cut in with more traditional coverage, but it also gives you freedom to use the frame to help both characters.”

The cinematographer made frequent use of Clairmont’s SwingShift lens system, as he had on his previous project, the offbeat superhero adventure Spawn (see AC Aug. ‘97). He found this system to be particularly useful for shooting in-car conversations which required that the faces of two characters be in focus, and for lending dramatic tension to certain scenes by bringing together or pulling apart the actors’ faces. Navarro details, “In one sequence, Jackie is in court being arraigned on charges of cocaine possession. One shot includes both the judge behind his podium and Jackie back in the gallery seats, and we brought the shot together at the moment when he is deciding her fate. We had to swing the lenses drastically, because its a very severe shot — a close-to-the-lens profile of her, and the judge way back in focus.”

Jackie Brown's final hour — set mainly within Torrance’s Del Amo Mall — is, in the director’s words, “very image-aggressive, consisting almost entirely of Steadicam moves following characters in real-time. It’s very voyeuristic.” Typical of Tarantino’s screenwriting style, this climax consists of one specific incident unfolding from the perspectives of several characters. The director notes that while the various viewpoints are subjective, they add up to an objective conclusion; in the end, the audience is able to put together all the pieces of the dramatic puzzle.

Steadicam is also utilized in the film’s opening credit sequence, which introduces Jackie Brown as she sashays through the bowels of Los Angeles International Airport. According to Tarantino (who recalls the actress’ impressive reveals in Coffy and Foxy Brown) this segment was designed to be “the coolest Pam Grier opening sequence in film history.” The lengthy shot follows Jackie as she glides along several automated walkways (also known as “people movers”) and navigates hallways backed by huge bay windows revealing airplanes in transit; the climax of the camerawork is a nearly circular pan and track of a departure lounge, where the stewardess approaches a ticket counter.

Steadicam and A-camera operator Dan Kneece recalls his work on the shot: “I stood in a grip wheelchair with the Steadicam and a 50mm lens, as they pushed me alongside the people movers — in the film, you float along with her as she’s gliding. We then had to slow down as she stepped off into a carpeted area, and speed back up to take her along another people mover. She was always getting on and off the movers, so there had to be a very smooth transition [between the moving and stationary surfaces].

“At the end of the run — as she hits the last people mover — I leaped off the wheelchair. I had her framed head-and-shoulders through that part of the terminal and around to the gate. But the shot couldn’t look as if I was coming off a wheelchair; it had to look seamless and flowing. We did it with a straight Steadicam — no gyros. Just as we got to the gate, someone offscreen was there to deliver a line, and I whipped over to pick it up in a tight close-up. Finally, Pam came walking up to the background, and we picked her back up again — it’s a very exciting shot.”

The practical sources inside LAX varied enormously and included fluorescent, mercury-vapor and tungsten fixtures. Despite this kaleidoscopic collage of color temperatures, only the fluorescents were swapped out with color-corrected tubes. Even though mercury-vapor lamps tend to emit a noticeable green spike on celluloid, most of these were left untouched. Navarro determined that Grier would only pass through them intermittently while being carried along the people movers. He also notes that “sometimes we couldn’t replace the fluorescents, because we couldn’t find color-corrected tubes to fit some of the older fixtures. I did a lot of shooting with magenta correction on the lens, and for some scenes, we had to add green gels to the lights.”

Gaffer David Lee says that the crew’s lighting setup for this sequence brought to mind a moving locomotive train: “Key grip Rick Stribling and his crew put together these huge 16'-long Obie lights — one for each of the walkways — so that we would always have color-corrected fill lights moving with the camera. They were four 4' Kinos in a line, rigged up to the ceiling and cantilevered out and over camera, all mounted to doorway dollies. We also had a Wall-O-Lite rigged to a cable cart with an inverter and some car batteries. We led Pam with that to get some frontal modeling on her.

“It was quite a setup. Pam would start walking down a people mover, at a pretty good clip, with two grips and an electric towing a doorway dolly and its 16'-long Kino rig. Meanwhile, Dan Kneece was tracking her with his Steadicam as the dolly grip pushed him along in a wheelchair, and electrician Deke Keener and I were leading her with the Wall-O-Lite on the cable cart. When we hit the end of one ‘people mover,’ the traveling Obie rig would have to stop as Pam walked in front of a long stretch of windows. We would race ahead with our Wall-O-Lite to be ready to catch her on the next walkway, where another 16' Obie rig was standing by. As we raced along like this, Quentin was yelling ‘“Faster, faster!’ Pam would start jogging and we would be running along, trying to keep up with her while hauling these massive rigs. Finally, at the end of the shot, we had to dive out of the way so that the camera could get past us and do a 270-degree panning/track.”

The beachfront apartment inhabited by Robbie’s bimbo girlfriend, Melanie, offered a multitude of lighting challenges during the production’s week-and-a-half-long shoot there. The close quarters of this Playa Del Rey unit left little room for crew and camera operator, and its bright white walls offered constant glare generated by sunlight blasting through two large picture windows facing the Pacific Ocean. Navarro relates, “Obviously, we had the problem of the sun hitting the windows at the end of the day. We were also shooting very complex interactions involving three actors — Sam Jackson, Robert De Niro and Bridget Fonda — each of whom had to be lit in a particular way. On top of that, Quentin wanted a lot of Steadicam shots that would rove and turn around in the same shot. Instead of trying to solve any of the ‘problems’ we’d find, I tried to work with the location and the interaction between the characters.”

Many of these interiors required an unobscured beach vista to be seen through the two westerly windows; effecting sunlight through the panes therefore ran counter to the scene’s demands. Navarro and his crew managed to solve this dilemma by setting up exterior lighting rigs just outside the camera’s field of view: multiple 18K and 6K Pars on a Condors. Interior illumination was made easier through the use of Source Four theatrical fixtures. Recalls gaffer Lee, “One shot brought Sam Jackson and Pam Grier in the front door of the apartment and out to the balcony in a 180-degree tracking pan, which hinged around Robert De Niro sitting on a couch in the middle of the room. The camera was on the Steadicam with a very wide lens; of course, the lens revealed everything in the room, so there was nowhere to hide the lights except for right over the couch. To light him, we put silver cards just out of frame along the walls; over the couch, we rigged 12 Source Fours with 3/4 CTB on them, which we bounced into the cards. Even with the filtration, they were bright enough to get us to the level we needed, but they were small enough to be rigged overhead and remain out of the shot. The control they gave us allowed us to focus them precisely without using a lot of flags for spill. When De Niro sat down to do the scene, he looked up and saw all of these lamps suspended over his head and gave a little shudder.”

The crew found no solace in Jackie’s Hawthorne apartment, which was equally cramped. This setting is the backdrop for a confrontation between Jackie and Robbie, during which the two characters ratchet up the tension by taking turns at tweaking the knob of a standing halogen lamp. This three-minute-long night interior begins with the lamp on, falls into silhouette as the shiftless con man dims it down, and ends with the air hostess turning up the light as she regains her moral footing. Tarantino explains, “I liked the idea of pulling off a scene with two black actors and no light. I wanted to do it without cheating — turning the lights off, but still allowing the viewer to see everything. We wanted darkness with a rich depth. There’s one moment when Jackie opens up the refrigerator as she’s making Ordell a screwdriver; the refrigerator light becomes the only source. Sam is dressed entirely in black, and the only thing that holds any light is his glass, because the drink is orange. Pam has a white blouse on, and she literally walks into complete darkness; you can’t see anything for two beats until she turns the halogen lamp back on. Then Sam walks over and dims it down again — it’s very spooky.”

Kneece adds, “I was tracking Pam [with a 25mm Zeiss Superspeed lens]. When the light went out, I had to guess where she was going to end up when she turned the lamp back on. She actually ended up silhouetted against a window, so we played a lot of the remaining dialogue that way. We did this all in one Steadicam shot, which was difficult because the video monitor went dark. Although we did have the ability to ride the exposure by using our focus system and one of its motors for adjustment, we didn’t do that in this instance; the scene was lit in such a way that when the lights went out, the majority of the picture — except for the window — went black. At the end of the scene, the lights went back on at a proper exposure level.”

Due to the lack of space in Jackie’s digs, standard filmmaking fixtures were out of the question. The space’s primary illumination was generated by a quartz halogen torchiere and bounce-fill cast by tiny MR-16 units and the type of 150W globes typically used in vanity mirrors; additional fill emanated from Source Fours. Lee comments,

“Quentin was adamant that the actors should be able to control the dimming of the lights themselves. He didn’t want Pam to have to pretend to flip on a switch while an electrician tried to match her actions off-camera. Therefore we wired up all of the lighting to dimmers and patched them together so that they were all controlled by the dimmer on our practical lamp.

“We were shooting the Vision 500T 5279 stock, so we didn’t need a lot of light. The walls of the set were painted a dark maroon color, but the ceilings were still white; the light from this torchiere bouncing into the ceiling was almost enough illumination by itself. We simply added a few more bounces where we could. The lighting was a bit flat, but the scene was more about the light going on and off rather than any one particular look. There was quite a difference between the two looks in that scene. When the lights were off, it was almost completely black; we added a bit of light outside so Pam and Sam would be silhouetted against something when they were by the window, but it wasn’t much.”

One of Jackie Brown's most extreme lighting setups illuminates Hawthorne’s now-defunct Cockatoo Inn during a conversation between the stewardess and bail bondsman Max Cherry (Robert Forster). The pair are sitting in a booth so suffused with red hues that, according to Navarro, “the frontier of black skin and white skin [between the respective actors] is completely abolished.”

The cinematographer had some of the room’s fixtures swathed with Lee’s 106 Primary Red gels; these lights were augmented with Source Fours bounced into white cards and some softer silver cards for a more governable ambiance. The scarlet shading, however, often proved too overwhelming. To lend the crimson monochrome a spectrum balance, various gels from Rosco’s Cal Color System were placed on top of the Lee Primary Reds. Cal Color System gels are available in primary and secondary hues — green, magenta, red, blue, and cyan — in predetermined increments. Explains Lee, “[If we hadn’t used Cal Color,] it would have been difficult to find a particular gel which matched the Primary Red in hue but was not as intense a color. Our options would have been limited if we had felt that the red on Pam’s face was too oppressive. To try and retain some control over this strong red color, we used different values of Rosco’s Cal Color Cyan. With them, we were able to control the redness of the gel in known amounts simply by adding a few points of cyan as needed. We would also add one of the Cal Color Reds to make sure that the few white lights working in the scene would read as neutral in tone.”

The ensuing drama leading up to the film’s climax occurs in the South Bay’s sprawling Del Amo Mall, which the production occupied while the facility was open during regular business hours. As Lee details, the crew faced a lighting situation similar to the one they’d worked with at LAX: “We didn’t have the ability for extensive control because we were shooting in a working mall when all the stores were open. One of the few places we could actually rig lights out of the public’s way was in the food court, but that only helped us for the specific area of action [around actors Pam Grier and Robert Forster]. We had to let all of the other sources around them go uncorrected. There were sources of every type: daylight-matched fluorescents, tungsten-matched fixtures, sodium mercury vapors, neon and regular tungsten. We could have sent in a team with thousands of globes to change out all the fluorescents and tungstens and to turn off all of the discharge sources, but there would have always been another store in frame which we had missed.”

The centerpiece of the film’s last act is a sequence in which Jackie heads up a police sting operation in Macy’s (renamed Billingsley in the film), swapping a department store bag containing $500,000 worth of marked bills — a ploy designed to ensnare Robbie in the police booby-trap. Unbeknownst to both the cops and the criminals, however, the savvy stewardess has planned a multiple double-cross designed to leave her both scot-free and rolling in dough.

The production had access to Macy’s for two consecutive nights. Navarro notes that this sequence shot almost entirely with the Steadicam, was “built on the respective perspectives of the different characters in the scene: Jackie, Louis Gara and Melanie Ralston, and finally Max Cherry. The scene plays out repeatedly from their different viewpoints as they weave behind and around clothing racks in the stores, and in and out of the changing rooms. The Steadicam was a great help in creating the dynamic of each character’s subjective point of view.”

One particular shot, for example, trails Jackie down an escalator, through Macy’s and into the mail’s main hallway, ending in a 360-degree circular tracking shot which conveys her panicked state of mind. Says Lee, “The scene itself is about having those shots from the different angles and being able to cut between the various points of view. Guillermo felt that it was more important to be able to shoot freely than to light each shot to the fullest.

“Like any department store, Macy’s has lots of tungsten spotlights, accent lights and fluorescents. We swapped out all the fluorescent tubes so the scene would at least be tungsten-balanced, but we shot with mostly available light. We added a couple of Wall-O-Lites where we could and a couple of lights up in the drop ceiling. Once again, we did a lot of traveling — walking with either lights or bounce boards. We couldn’t count on having enough time to put a light up, take it down, and put another light up somewhere else to relight for another shot.”

With Jackie Brown in wide release, Tarantino is currently executive-producing both a prequel and sequel to From Dusk Till Dawn. His next feature as a director is tentatively slated to be a period prison picture, which he describes as a “Western-genre Papillon.” Navarro, meanwhile, is prepping a Caribbean shoot for the action thriller Deep Sea Blue, his second collaboration with director Renny Harlin (they first teamed on 1996’s The Long Kiss Goodnight, both movies also starring Jackson).

“I’ve been able to build good relationships with the directors I’ve worked with, so we tend to collaborate again,” Navarro says. “I’ve had good experiences with Robert Rodriguez, Renny Harlin and Quentin. Collaboration is somewhat of a cold word to describe what is a very strong bond — making movies is very demanding, both emotionally and physically. It’s a big chunk of your life, and it can become a very existential experience.”

Navarro was invited to join the ASC in 2000.

If you like archival production coverage, you'll find our complete collection here.