John Knoll on Rogue One’s Visual Effects: Part 2 of 2

ILM’s senior visual-effects supervisor details the effects work for this Star Wars story.

Unit photography by Jonathan Olley, Giles Keyte and John Wilson. All images courtesy of Lucasfilm Ltd.

In Part 1 of this interview, Industrial Light & Magic’s chief creative officer and senior visual-effects supervisor John Knoll spoke about the overall style of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story and specific advancements made for the movie’s two digital humans: Grand Moff Tarkin and Princess Leia. In Part 2, Knoll — who pitched the story that would become Rogue One and served as the feature’s visual-effects supervisor alongside Mohen Leo — begins with a discussion of the movie’s CG vehicle models.

American Cinematographer: Was there any miniature photography for Rogue One?

John Knoll: No, but at the beginning we talked about where we might want to use miniatures on the show. I was a model maker when I started my career, and then I was a cameraman shooting miniatures for years, so I’m very comfortable with that. But this show had a pretty compressed post schedule, and one of the things that’s always a challenge when you’re shooting miniatures is just getting all of the elements done if you’re doing a large scene where the miniature would show up in a lot of shots. If you only have one [miniature], you can only have one crew shooting it at a time. So you need to think about, ‘How many elements can I get in a day?’ and ‘how many days do I have?’ With a digital model I can have any number of lighting TDs [technical directors] working on lighting the same [digital] model and putting it into their shots, so we can run lots of shots in parallel. And then there are director comments, editorial comments, and there are often tweaks and changes that need to happen. If it’s a photographed-miniature element, it’s not possible to go back and make adjustments. So it’s the additional flexibility that comes with the CG models that’s very attractive to many people.

“It’s been really fun to play in this universe again.”

I imagine it’s probably not surprising that for our space battle we would have shifted to doing these shots digitally. But we wanted them to look every bit as good as if we’d shot them with miniatures. We’re trying to capture that same look, and there are a couple of components to that. For the last bunch of shows [at ILM], we’ve been using [CG] materials that have very accurate reflectivity responses — the materials just look more realistic to begin with.

I also wanted to emulate the kit-bashing aesthetic that had been part of Star Wars from the very beginning, where a lot of mechanical detail had been added onto the ships by using little pieces from plastic model kits, with racks and racks of model-kit artillery pieces, tanks, Formula One cars and that kind of thing. I thought that if we approached our digital models the same way the miniatures had been built, we could get a similar result. So we got a bunch of the original model kits that [original trilogy model maker] Paul Huston and a bunch of others identified. We scanned them, and we made CG models of a lot of those individual pieces, and then we used those to build a Star Wars-themed parts library. So when we were building our models and we needed to put in mechanical detail, we did them with the digital equivalent of what had been done in the day, where the modelers would browse through that kit library and pull little bits and pieces and fit them in. And my hope was that if we could enable the digital version of that workflow, the results would capture that same aesthetic. And I’m very happy to say it was super-successful. I think a lot of our digital models look like they are motion-control models.

Were there instances when your CG models for any of the ships that appeared in A New Hope had to deviate from their original physical counterparts?

Knoll: The Star Destroyer is a good example of that. Story-wise, this takes place right before Episode IV, so I felt like the Star Destroyer we see should look like it’s the exact same design as the one seen at the beginning of Episode IV. There was a 3-foot motion-control model that was built for A New Hope, but as beautiful as that model was, it was insufficiently detailed to hold up to what ILM needed it to do on The Empire Strikes Back, so they built an 8-foot-long model for Empire that had lots more detail and internal lighting. That original 3-foot Star Destroyer model from A New Hope had no internal lighting. This is going back to, ‘Do you match what you remember or how it actually was?’ It wasn’t even a question to me that our Star Destroyer should have all of those lights, but those were not characteristics of the 3-foot model. Generally we copied the 3-footer for details like the superstructure on the top of the bridge, but then we copied the internal lighting plan from the 8-footer. And then the upper surface of the 3-footer was relatively undetailed because there were no shots that saw it closely, so we took a lot of the high-detail upper surface from the 8-footer. So it’s this amalgam of the two models, but the goal was to try to make it look like you remember it from A New Hope.

With a ship like the U-wing, where the art department was responsible for crafting pieces of it for the actors to interact with and you needed a full digital model for the visual effects, did one department lead the other, or were you working simultaneously and comparing notes to make sure your versions jibed with one another?

Knoll:We tried to make postproduction as ‘post’ as possible, so that we weren’t building too much work prior to it being built as a set. So usually we’d defer. The idea was if something was going to need to be built both ways — and the U-wing is a perfect example of that — we didn’t want to build our own version of it while the art department built their version of it, and then we’d have to deal with the differences between the two. We’d wait until they were done with theirs, get a lidar scan of it, get good photo reference, and then we’d build our model from that.

But that said, the U-wing was a design that had to be approved fairly early on. One, because we had to build a full interior set and a partial exterior of it; and two, there’s this additional dimension with the Star Wars movies: merchandising. Things that are going to be toys need to have approved designs, and they need to go off to all the folks who are going to be making the toys. So we had a deadline that was, I think, April or so of [2015], before principal photography even began, and we had to lock-off on the design of the U-wing for all the third parties. So we approved the design, and then they started building the set, and the set was underway and it couldn’t really be changed at that point. But then Gareth was looking at some of the final paint designs for the exterior, what it would look like in shots of it flying, and he wanted to change the door line and a couple other proportion features. The set was already being built and couldn’t really be changed, so we decided, ‘Okay, our exterior model of it can be different than the set.’ And that was generally okay, except we’ve got a few places where we shot somebody climbing into or out of the live-action set, and we have to extend the rest of it with the digital model, which is a different shape than the set piece. So, for things like that, we had to have a second version of the exterior that was a closer match to how the set was built.

Was there much overlap between visual effects and Neal Scanlan’s creature-effects department? Were there characters both departments had a hand in realizing?

Knoll: For the most part the creatures have been more fully realized as practical effects on set, but I can point to a couple of characters that were practical but had things to paint out on them. We had a droid at the beginning that was controlled by performers from outside [the frame] and we just had to paint out the rods. And there are some characters in Jedha City whose design was such that you couldn’t put it over a performer without part of the performer sticking out.

Then there’s K-2SO [Alan Tudyk]. His design precluded there being someone in a suit because he’s this tall, thin droid with a very thin neck and thin wrists. So at the beginning of the show we talked about, ‘What’s the right split?’ For a while we were thinking, ‘There are going to be a lot of head-and-shoulder shots of Kay-Tu — could we build a practical puppet and use that on set?’ But the more we talked about it, the more it seemed like that was not a good allocation of resources, and if we’re going to have to do full walking, talking, waist-up shots and that kind of thing, then [visual effects] might as well just do the rest of it as well. So, even though Neal’s group did the design of Kay-Tu, we did all the execution here at ILM.

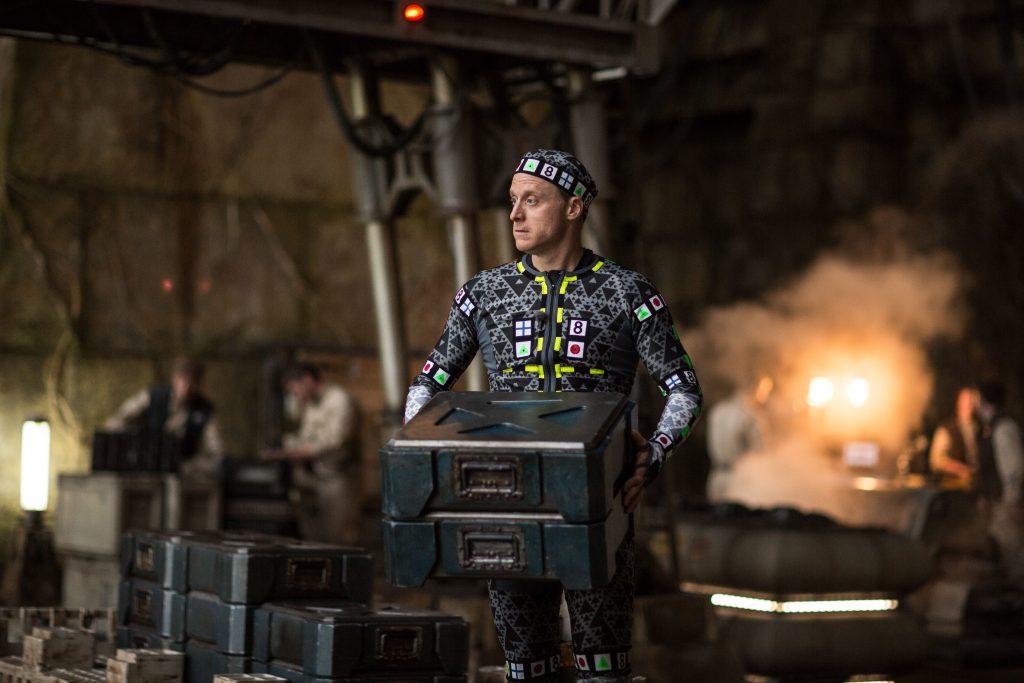

With K-2SO, did you get all of Alan Tudyk’s motion-capture work live while he was interacting with the other actors?

Knoll: Yes, exactly. He was on set in a motion-capture-friendly suit so he could interact with all the other characters. Performance is always better when two actors can be present at the same time and look into each other’s eyes and base their performances on what the other is doing. And it’s good for camera, too. If camera operators have something they can frame on, the camerawork is always better than if you’ve practiced with a stand-in performer and then you have them step out and shoot a clean plate.

Kay-Tu is basically human-proportioned, but he’s a little tall. So we had these motorized stilts for Alan that had a micro-controller in them and a motorized ankle joint. They’re made for amputees, and the way they behave is much more natural to walk on because they move like a real ankle does. We had boots made for him that connected to stilts, and each stilt went down to a sort of bionic foot. Alan learned how to use them very quickly — I think he spent a day walking around and getting used to them, and he could walk extremely naturally with them. That put his eyes up at the right height so that when he was performing with other actors, they could look into his eyes and the eye lines would be correct.

What’s the pace of work been like? How many visual-effects shots are in the finished movie, and what’s been the calendar for completing them?

Knoll: It’s about 1,700 shots, and as of yesterday [Nov. 3, 2016] 1,200 or so were finished, with about 450 remaining and two weeks left to go. So it’s busy. But that makes it sound a little worse than it is, because everything is underway. There are no shots that we haven’t started on yet, and many of them are very close to being done. At this point we’re finishing out 200 shots a week, which is a very rapid pace, but we’ve got a great crew of really talented artists who are just knocking it out of the park.

My last question: If you had the opportunity to tell the 15-year-old you who first visited ILM what you’re up to today, do you think he could possibly believe it?

Knoll:[Laughs.] Oh, I don’t know. It’s a little hard for me to believe now. It’s been really fun to play in this universe again. George Lucas created this vast playground, with zillions of planets and characters, that spans this large timespan. There’s almost an unlimited number of stories that can be told in a universe that rich. We’ve barely scratched the surface.

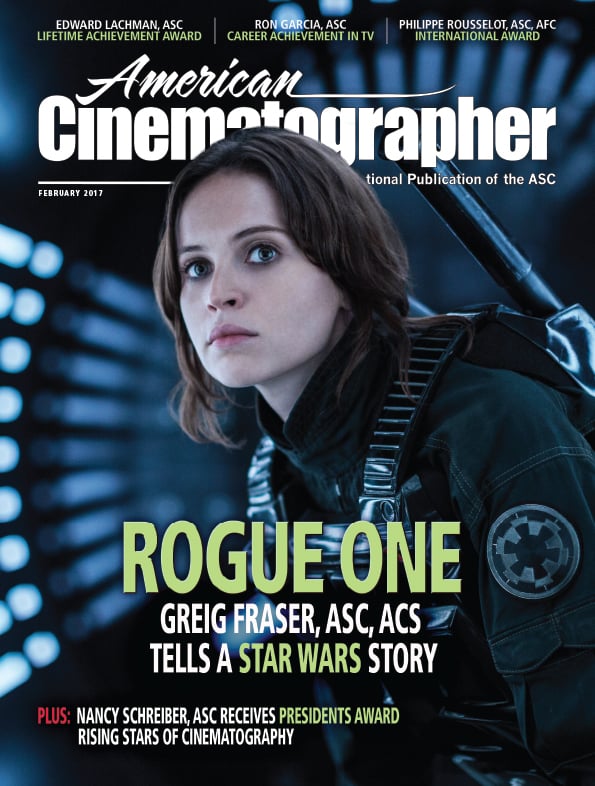

See our February issue of American Cinematographer for the complete production story on Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS's cinematography in Rogue One.