Joy and Sorrow: Belfast

Haris Zambarloukos, BSC, GSC revisits a tumultuous era in Northern Ireland’s history with Kenneth Branagh.

Photos by Rob Youngson, courtesy of Focus Features

Belfast is a beautiful and sensitively shot film about a Northern Ireland family that gets caught up in the “Troubles” between Catholics and Protestants, forcing them to decide whether they should stay or leave. It is also a shining example of collaboration between a director and a cinematographer who seem to read each other’s minds.

Based on the early life of writer-director Kenneth Branagh, the black-and-white picture marked the seventh collaboration in 15 years between the director and cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos, BSC, GSC. The duo’s eighth collaboration is set to premiere in 2022.

Branagh has called Belfast his “most personal film,” and the close relationship between the director and the cinematographer underpins the entire picture, illustrating the visual support from Zambarloukos that allowed Branagh to retrieve very personal memories from his childhood years in Northern Ireland and recraft them into a fictional narrative.

“The Irish are made for leaving,” one of Belfast’s minor characters says, referring to the Irish diaspora — the constant stream of emigrants from Ireland over hundreds of years. Branagh was born in Belfast in 1960. His family moved to England when he was 9 to escape the escalating violence between Catholics and Protestants across Northern Ireland, which would ultimately last 30 years and leave more than 3,500 people dead. Perhaps not coincidentally, Zambarloukos also comes from a displaced background — he is a Greek Cypriot who was born in the main city of Nicosia, Cyprus, which was split in 1974 when Turkey invaded Cyprus and occupied a large part of the island. “My city is still divided,” says Zambarloukos. “I am sure in the subconscious, my friendship with Ken comes from that shared perception of the world — not giving up even after being forced to leave, and being willing to keep starting over again.

After completing his schooling in England, Branagh trained as an actor at RADA, the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts in London. Zambarloukos studied cinematography at the AFI Conservatory in Los Angeles. The two first met in 2006, when Branagh was looking for a cinematographer to shoot the feature Sleuth. Branagh had seen Enduring Love, a 2004 film shot by Zambarloukos, “and in particular [he] loved the opening balloon-accident sequence, and was interested in talking to me,” the cinematographer says.

The pair hit it off right away, finding they had very similar approaches to preparation. “Ken loves to plan, test and rehearse,” Zambarloukos continues. “He really immerses himself in the process of discovery, whether it’s a methodology of shooting, a concept [for the] look, or a deep insight into the human condition portrayed by the characters. At all times, he included me and the rest of the team in this process — we all contributed.”

The filmmakers went on to work together on films as varied as Thor (AC June ’11), Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit, Cinderella (2015) and Murder on the Orient Express (2017) — all of which, Zambarloukos says, “we approached with similar intensity of spirit.”

When they began talking about making Belfast, Branagh made it clear that he did not want to make a war film. “Ken did not want [the movie] to be something that emphasized boundaries,” Zambarloukos says. “It does not show much of the violence, or play to the stereotype of a war zone.”

Antagonism between Protestants and Catholics living on the same street is seen building throughout the film until it boils over into direct confrontation and British soldiers are brought in to maintain the peace. But despite the drums of war and the provocations of thugs seeking to provoke violence, the strongest emotional theme is the love between the members of the film’s central family: 9-year-old Buddy (based on Branagh and played by 11-year-old Jude Hill), his parents (James Dornan and Caitríona Balfe) and grandparents (Judi Dench and Ciarán Hinds). They find a way to be true to themselves and reject the ugly sectarianism that is on the rise, even as their lives are put under strain by their circumstances. Zambarloukos says that he and Branagh talked a lot about another exile — the Dalai Lama — while making the film. With a nod to mythology scholar and author Joseph Campbell, Zambarloukos says, “I admire the Dalai Lama a lot — how he dealt with all that hate and conflict, seeking ‘joyful participation in the sorrows of life.’”

The collaborators started prepping by walking through the streets of Belfast together, visiting Branagh’s childhood haunts. “I saw Belfast through Ken’s reminiscing,” Zambarloukos recalls. At a certain point, they stopped their historical scouting and dived into their fictional world as filmmakers. “You research a story, but however personal it is, it then becomes a film, not a documentary. Ken was generous with his trust, [saying,] ‘Tell me how we make this into a film.’”

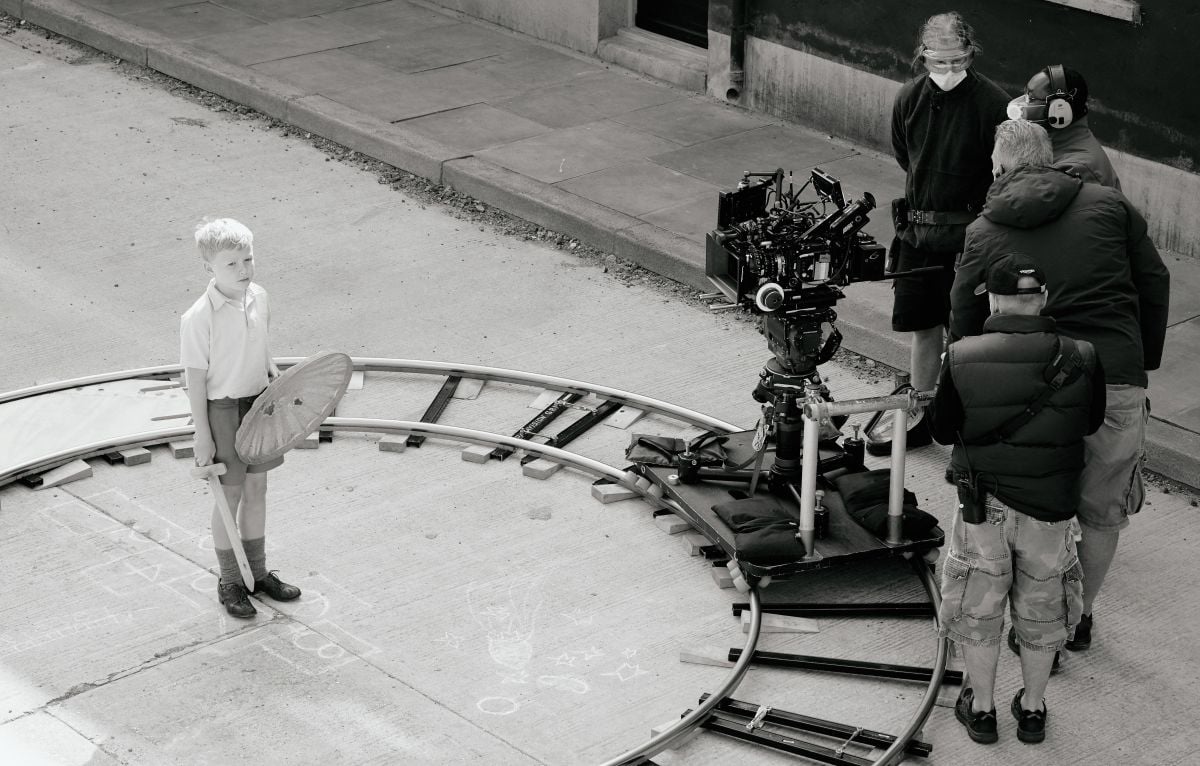

The duo aimed to reduce everything to the core intent of each scene, focusing on what was important. “That takes away a lot of unnecessary movement,” says Zambarloukos. “We are both inspired by still photography — Henri Cartier-Bresson, and also Philip Jones Griffith, who shot a lot in Belfast, particularly his famous image of the woman mowing her lawn [while a British soldier squats behind one of her bushes with a gun pointed out at the street]. When you have contrasts [like that], something special happens — we wanted to show those contrasts.”

Throughout his career, another inspiration for Zambarloukos has been Ansel Adams, and the photographer’s approach to preparation. “He almost wrote the book on how to imagine an image before you take it,” the cinematographer says.

Decisions about how to shoot the film were made together. “Ken has an incredible understanding of cinematography,” says Zambaroloukos. “This is only the fourth digital film I have shot — Ken brought it up, asking, ‘Is this one you would like to go digital on?’ I said yes. Film would have given us more grain. I thought the cleanliness and lack of grain with digital, combined with old lenses, might be an interesting look.”

The lessons of Ansel Adams were never far from his mind: “An important thing that’s sometimes ignored in digital is that you have to imagine a shot or picture before you pick up the camera. You have to thoughtfully plan an image, not just take it randomly.”

Zambarloukos used an Arri Alexa Mini LF equipped with large-format lenses — Panavision System 65s that were made in the early 1990s. “I use a particular set with very specific serial numbers. [ASC associate] Dan Sasaki [of Panavision] maintains them in L.A., and then they are shipped to London or wherever I need them.

“I shot with a single camera that I operated for most of the shoot,” the cinematographer adds. “We used a second camera and had Andrei Austin operate on the days with large crowds like the [days we were shooting riot sequences]. Andrei also operated all the Steadicam shots.”

Zambarloukos notes that he chose the System 65s because he is “very familiar with those lenses. I used the same set on Orient Express and [the Branagh-directed feature] Death on the Nile [set for release Feb. 11], which we shot on 65mm film. They cover the large sensor of the LF and they have a very pleasing falloff around the edges while staying sharp in the center.”

Digital photography, Zambarloukos says, “got interesting” with the advent of sensors larger than Super 35, like the Alexa LF and the Red Monstro. “That format got my interest. When combined with certain lenses, it gives you great portraiture. It makes the eyes sharp and expressive and the falloff softens any blemishes on a face. It feels immersive yet natural.

for this musical-performance sequence.

“I tried to stay wide-angle and close because it helps inform the audience of the character and the surroundings,” he continues. “With large format, a lens like a 40mm is very wide in its field of view — more like a [30mm] in a standard 35mm sensor — but never feels like a fisheye lens. It has the lens properties and depth of field of a longer lens.

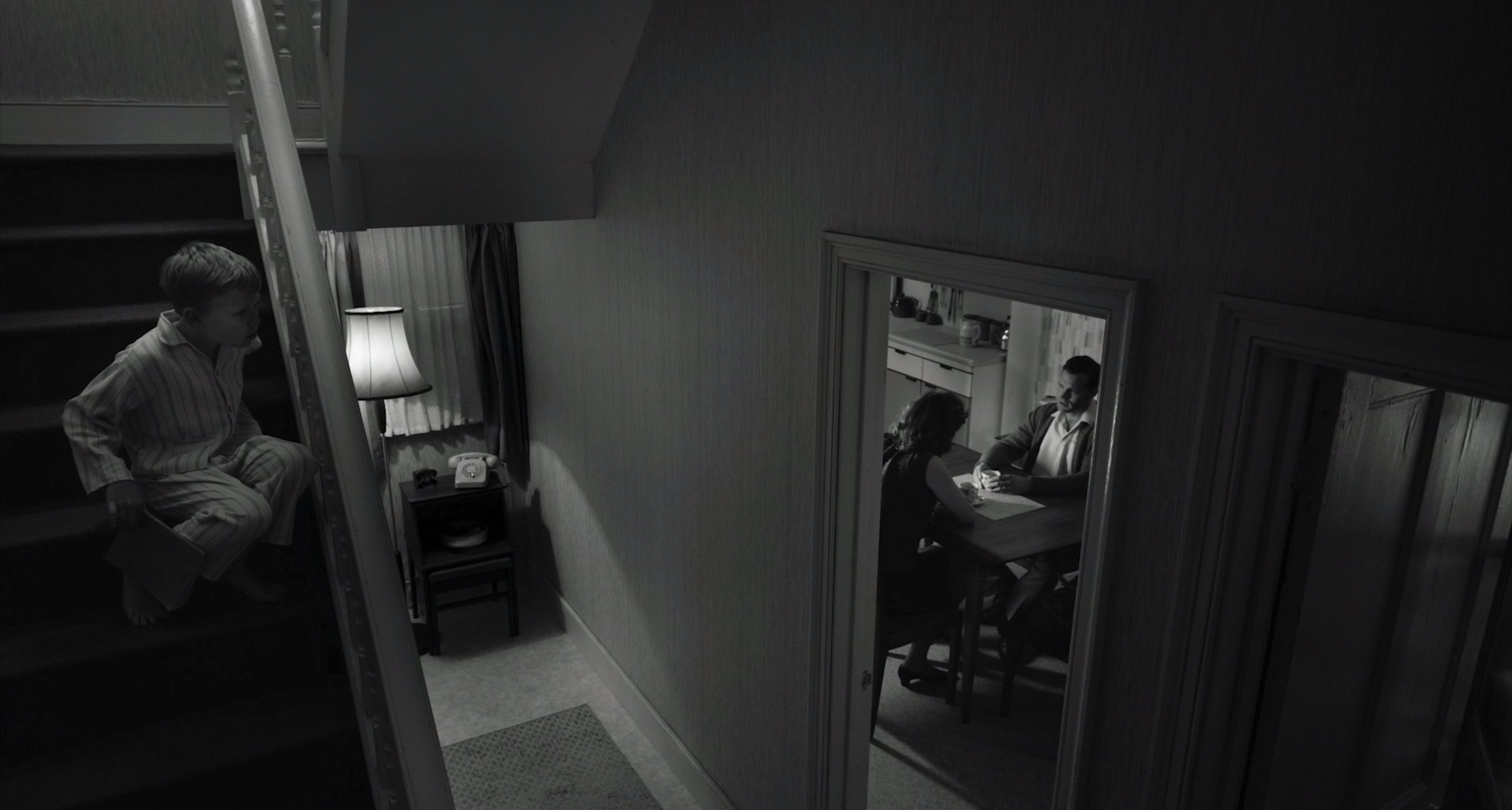

This enabled Zambarloukos to create a distinctive look for the film, shooting a number of scenes as if they were still portraits, with the faces of individual characters framed in windows, looking out on a troubled world. The strategy has the effect of slowing the film down to focus on the characters involved in the growing storm, encouraging the viewer to imagine how these people feel about their respective situations, rather than documenting the ugly events that surround them.

Shooting in black-and-white was also a joint decision. Zambarloukos recalls, “As we started working together on the project, I asked, ‘I’m assuming we’re shooting in black-and-white?’ and Ken said, ‘Of course — but with a little color.’” The film opens with some color scenes of Belfast as the city appears today, and scenes showing characters escaping their world for a couple of hours to watch a film in a movie theater are also shot in color, playing on the contrast of reality and fantasy.

“Black-and-white has this paradoxical, transcendental quality — it’s descriptive without giving you everything,” he continues. “You can show how people feel. The biggest part is removing the descriptive qualities of color and concentrating on the human condition. It creates a more honest portrait than color can.”

The cinematographer says he likes to shoot black-and-white with a color origin, “because I can manipulate it much further in the [color grade].” He mentions a scene where Buddy and his father walk along a path next to a field, happy to be sharing time together. The landscape feels radiant, reflecting their mood. “The grass in that field was yellow,” says Zambarloukos, “so I could key that and almost get an infrared look. You can make better black-and-white with a color negative or color acquisition.”

Nothing was off the table in discussions between Branagh and Zambarloukos. “We even got down to talking about how much depth of field we’d have, and what f-stop we should be using. We agreed that our favorite f-stop was 4, so I shot the whole film at 4 — or at least 80 to 90 percent of it. I went a little higher for some day shots. This follows the Ansel Adams approach — you have to decide in advance what your image is going to be, including depth of field.”

Throughout the production, the filmmakers made abundant use of the sky and negative space. “We let the weather be part of the scenes,” he says. “It would be cloudy and then sunny, very changeable. Whenever we had weather, we would frame up to include it in our shots — the opposite of what you would normally do.”

Movie lighting was very restrained throughout. “I wanted to use as little lighting as possible — there is barely an eye light in most shots,” Zambarloukos notes.

The cinematographer adds that he employed bounce and negative fill when shooting in natural light. “I used both a lot,” he says. “My gaffer Dan Lowe was always laying sheets of muslin on the floors to bounce backlight, or we would use frames of cotton poplin to diffuse light coming in through windows.”

To manage the changing weather for natural-light sequences, he says, “We often widened our frame to show the effect of the changing weather on walls or surfaces. We also committed to long takes, which took advantage of the fluctuating light. It gave a very ethereal effect.

“In the twilight shots [with vigilantes patrolling the streets on the lookout for troublemakers], all the lighting was practical from the torches they were carrying,” Zambarloukos says.

Regarding his occasional use of movie lighting, he adds, “I used a little light in the church scenes, and I used lighting to create the process work in the bus when Buddy and Granny are returning from the theater, and also in the movie theater. The ‘Everlasting Love’ [interior musical-performance] sequence used practical theater lights from the ’50s that we rigged in the location, which we could use in-camera.”

As the film moves toward its conclusion — when the family has to decide whether to stay or leave — their feelings of joy, sorrow, hope and fear follow in quick succession, like the clouds that scud across the skies above, altering the light in unpredictable ways. When the fateful decision is made, Zambarloukos’ camera follows Dench’s matriarchal character, and the (larger-format) image of her face tells a story of not just 1,000 words, but of the joys and sorrows, the loves and the losses, of centuries of troubled Irish history.

Zambarloukos and Branagh subsequently spoke about their work with interviewer Shelly Johnson, ASC in this episode of our ASC Clubhouse Conversations discussion series: