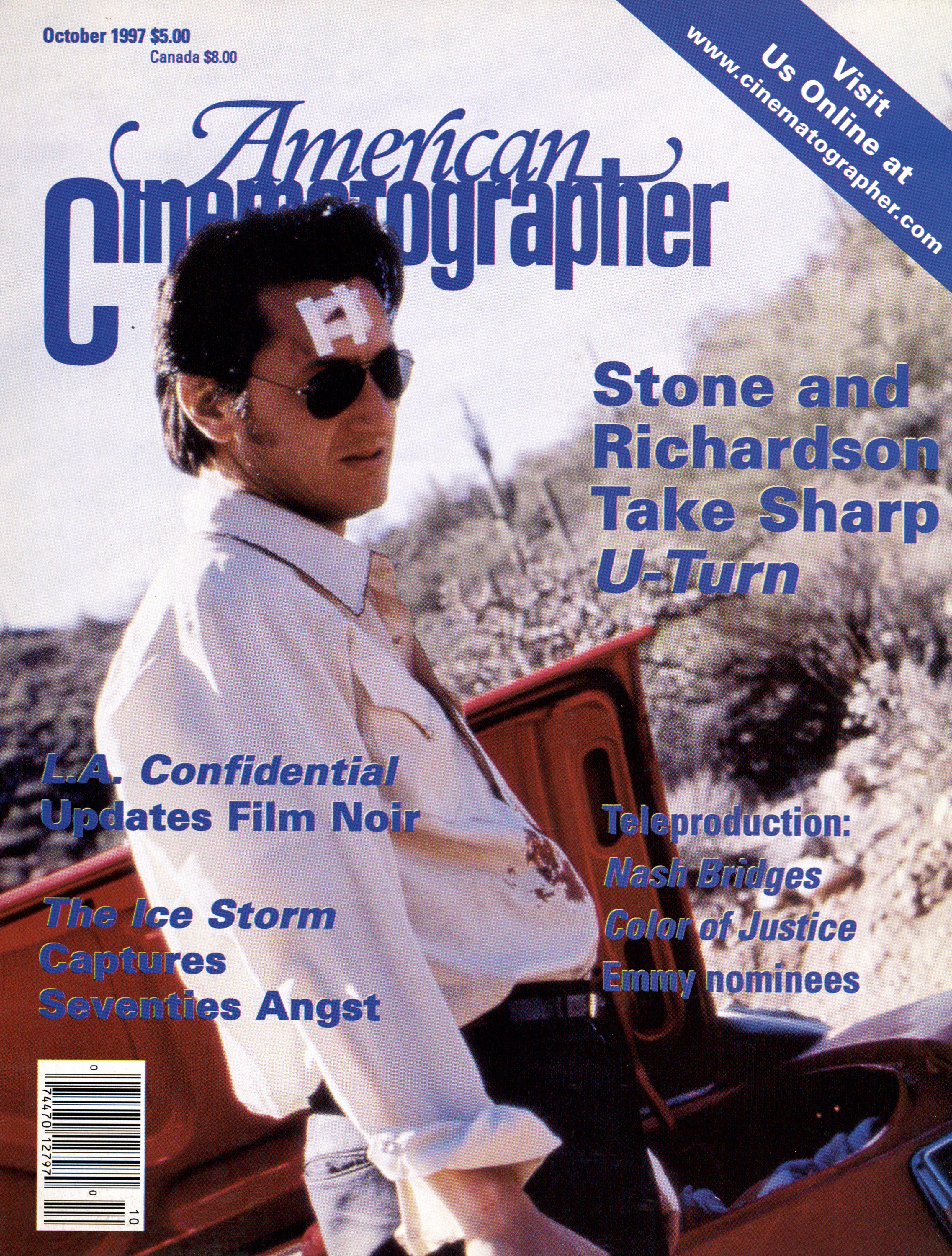

L.A. Confidential: Exposing Hollywood’s Sordid Past

Director Curtis Hanson and cinematographer Dante Spinotti, AIC add a realistic touch to this film noir story.

Unit photography by Merrick Morton, SMPSP

In 1953, the post-war boom was in full swing, particularly in Los Angeles, where wide new freeways and sprawling suburbs were dramatically reshaping the idea of the American dream. Boosters worked overtime to draw ex-GIs and their growing families to the sun and fun of L.A., touting the town's celebrity residents and wonderful weather.

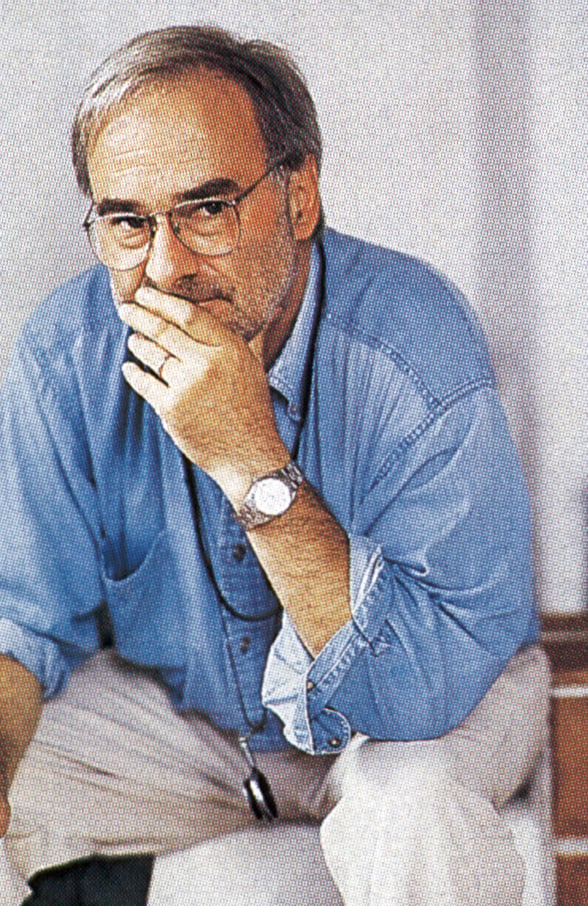

This paradise-on-earth veneer is as thin as a quick coat of varnish in L.A. Confidential, a screen adaptation of James Ellroy's novel of ambition and corruption run wild. Ellroy's dark world has been vividly brought to life onscreen by director Curtis Hanson (The Hand that Rocks the Cradle, The River Wild) and Italian cinematographer Dante Spinotti, ASC, AIC, whose credits include The Last of the Mohicans (for which he earned a 1992 ASC Award nomination, AC Dec. 1992), Manhunter, Beaches, Crimes of the Heart, Frankie and Johnny, True Colors, The Quick and the Dead, Nell, Heat (AC Jan. 1996) and The Mirror Has Two Faces.

“We didn’t want to create an homage to the film noirs of the past, nor did we want the period to the emotion and the action to be front-and-center.”

Although the setting and themes of L.A. Confidential are classic film noir, devotees of the genre who are expecting an updated version of the highly stylized and shadowy work of master noir cinematographers such as John Seitz, ASC (Double Indemnity, Sunset Boulevard) and John Alton (The Spiritualist, He Walked by Night) will have to look elsewhere. Hanson explains, "When people hear 'early Fifties' and 'Los Angeles' they think about The Big Sleep, Chinatown, and the world of Philip Marlowe from the Thirties and Forties. Our goal with L.A. Confidential was to be faithful to the period without telling the story through a lens of nostalgia. We didn't want to create an homage to the film noirs of the past, nor did we want the period to the emotion and the action to be front-and-center."

Rather than screening film noir classics for visual inspiration, Hanson and Spinotti pored over the work of Swiss-born still photographer Robert Frank. They were particularly intrigued by Frank's 1958 book The Americans, a collection of gritty, startling black-and-white photographs documenting American life during the mid-Fifties. Recalls Hanson, "I had seen an exhibition of the photographs Frank took across America in 1955 and 1956. They were of the period but had a contemporary look and feel. We wanted the same look for L.A. Confidential. Dante just leapt on the idea of approaching each scene in the film as if it were a Robert Frank still."

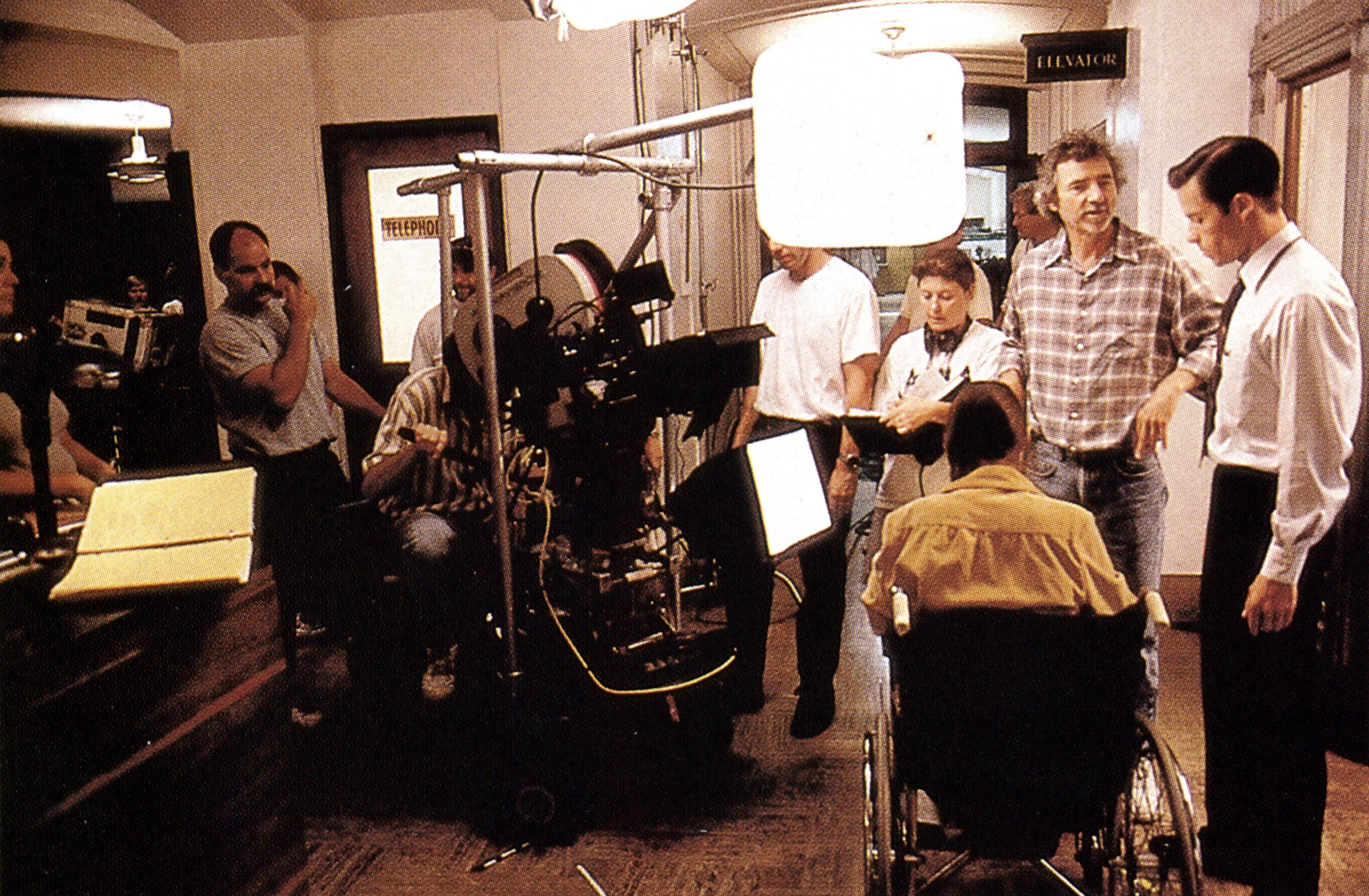

Spinotti found himself moved by Frank's "strong selection of elements, his way of bringing symbols into the shots. His work is passionate, but it is passion filtered with intellect. On L.A. Confidential, I tried to compose shots as if I were using a still camera. I was constantly asking myself, 'Where would I be if I were holding a Leica?' This is one reason I suggested shooting in the Super 35 widescreen format; I wanted to use spherical lenses, which for me have a look and feel similar to still-photo work. We would also be shooting a lot at night. With anamorphic lenses, which we used on Heat, you are limited to a stop of f5.6; with spherical lenses you can open up to f2.8,2.3 or more and still get a very sharp image. We also wanted to have the ability to move around and use Steadicam, which is easier with spherical lenses."

The director and cinematographer agreed that Robert Frank's influence resonates in almost every aspect of the film's look, from lighting and camera angles to the selection of locations. Spinotti was particularly fascinated by the photographer's inclusion of "practical" lights in his photographs, noting, "I told the production designer, 'You will love this film, because what you select as practicals will be our major sources of light.' In fact, practicals were quite often our key lights on this film.

Hanson adds “the selection and employment of practicals on L.A. Confidential was critical; our location scouts were told to look for opportunities to utilize practicals for the actual lighting when they selected locations."

Frank's 35mm black-and-white photographs in The Americans were all taken with available illumination, usually in very low light situations (a tactic that required audacity and great skill, due to the limits of the era's relatively slow-speed film). His light sources — whether a glaring bank of overhead fluorescents in a gritty cowboy bar in Gallup, New Mexico, or candlelight at a high-society charity ball in New York City — were often included in the photographs, and became an important part of the compositions.

Was Spinotti concerned about the problem of practical key lights "burning out" on screen? "No," he answers. "In fact, I wish I could have burned them out more, because I like that look. As you look at Frank's photographs, you see there is often a halo around the lights. These halos are one of the things people are often struck by in his work. I think that 'burn-outs' and halos worked for us as well in L.A. Confidential, enhancing the period and mood."

Practical fixtures have their limitations, of course, and Spinotti bolstered them with the extensive use of one of his favorite lighting tools: bat strips. These fixtures are 4'-to-8' long strips of reflector floodlight bulbs, often R20's, mounted very close together. "I call bat strips my 'no-light lights," says the cinematographer. "We hung them in corners of rooms, near the ceiling aimed down at the actors, especially when space was at a premium. They create a very soft fill or backlight which works wonderfully on furniture and hair. They were very effective on Kim Basinger's blonde hair. The trick is to keep the R-20 bulbs close to each other, about a half-centimeter apart, so they don't cast multiple shadows, but rather produce one long line of soft light. We also used bat strips vertically when we were tight for space; they helped us to light actors in full-body shots."

L.A. Confidential centers on three Los Angeles police detectives. The first, Jack Vincennes (Kevin Spacey), is a cop who has "gone Hollywood." He serves as the technical advisor to a Dragnet-type television show and covets the cult of celebrity provided by this gig. Vincennes also specializes in drug and morals busts meticulously engineered by pioneering tabloid editor Sid Hudgeons (Danny DeVito), who gleefully reports on the arrests in his tell-all rag. Vincennes is rewarded with fame and large-denomination bills passed on furtively by Hudgeons.

The crooked Vincennes becomes embroiled in a murder investigation that links him tragically with two fellow detectives: the thoughtful, bespectacled Ed Exley (Guy Pearce) and tough-guy Bud White (Russell Crowe). Matters are complicated by the imprisonment of a Mafia drug kingpin, whose illicit empire suddenly goes up for grabs. Exley and White soon become dangerously linked to one another through their shared relationship with high-class prostitute Lynn Bracken (Kim Basinger), and the fact that they both know who has assumed command of the lucrative drug empire.

The world of L.A. Confidential is one in which reality is constantly shifting. Reasons Hanson, "A key theme of this film is the difference between appearance and reality, such as the contrast of L.A. as this glorious fantasy land with its gritty commercial reality.

"We had a beautiful opportunity to examine this theme through Kim Basinger's character, Lynn Bracken, a prostitute who makes herself over to look like the glamorous Forties movie star Veronica Lake," Hanson adds. "With Bracken we were able to emphasize that nothing is what it seems to be, and also highlight the difference between traditional film noir cinematography and our much more naturalistic approach."

This contrast is presented visually in one particularly clever scene. "When we first meet Bracken, she is screening the 1942 Veronica Lake-Alan Ladd film This Gun for Hire [photographed by John Seitz, ASC] in her living room," Hanson notes. "We see Lake and Ladd onscreen, lit in that wonderful classic Forties noir style. After a camera move, Kim appears, lit in our style, right in front of Veronica Lake's image. You see that this image on the movie screen is what Basinger's character is pretending to be. You also see the classic look of 1940s film noir, directly contrasted by Dante's more naturalistic approach, and it becomes clear that we are doing something different in L.A. Confidential."

Despite his departure from the classic film noir style, Spinotti did include some traditional motifs in his overall photographic approaches, such as the occasional appearance of menacing, exaggerated shadows, or shadows cast on walls by Venetian blinds. One of the more notable visual aspects of L.A. Confidential is the cinematographer's use of darkness to surround and highlight the most important aspect of each scene, much in the way that early filmmakers actually vignetted the edges of a scene to emphasize its vital elements. He explains, "I like to shoot dark images. I'm drawn to the mystery of darkness with brightness in the center; that's instinctive to me."

Hanson was impressed with Spinotti's dedication to the realistic visual approach they developed. The director offers, "The thing that was striking about Dante was the consistency with which he went after this naturalistic feel. His basic approach in L.A. Confidential was to employ strong source light, be it a large window or a house lamp, and then very specifically work from that as the key light. He augmented and enhanced the practical key lights as needed, but kept everything he added to a bare minimum, so you get the feeling that nothing is being done. This approach, where the style is defined by the apparent absence of style, can be quite effective. The cumulative effect is that you realize that someone did something rather remarkable. The photography is exciting, and it adds to the veracity of the story."

The filmmakers' emphasis on naturalism, subtlety and practicals did not prevent Spinotti from creating some memorable fantasy images, however. In a scene that leads to the initial coupling of Lynn Bracken and Bud White, the cameraman thoroughly dispenses with reality in favor of romanticism. "Bud comes in through Lynn's downstairs living room, where she has her 'working' bed," Spinotti details. "The room is lit with an HMI placed outside the large window, gelled with quarter to half blue. This blue environment looks a little bit like an aquarium."

A striking addition to the cool bluish light downstairs is a flame-like play of brilliant pink and orange light. Spinotti created this richly colored splash after he noticed that a light planned for a high position worked more effectively low to the ground. "To mimic the sun, I had a Xenon light that was going to be placed high up on a Condor outside of the house's big windows. However, when we lit the Xenon while it was still on the ground, we saw that it produced this striking effect of sunlight coming through the big window at an extremely low angle. I liked it and left the light down low, adding orange and magenta gels. The result is this really unusual effect of a very low early-morning sun that is pink and orange at same time, rather than just yellow."

When the couple enters Bracken's upstairs bedroom, the warm, low-angled pink and orange light becomes much more pronounced, playing dramatically against the walls and creating a strong contrast to the cool blue that dominates the previously seen "business" bedroom.

interior is

illuminated

with a Chimera

softbox, which

Spinotti often

employed to

provide a more- angled

directional

light.

Due to scheduling conflicts, the lighting for Basinger's close-up had to be created on the fly. Recalls Spinotti, "We shot Kim without the benefit of tests, and this underlined for me the fact that you have to find the proper way to light each and every face, no matter how beautiful. I tried several approaches, but the best involved keeping the light on the same side of her face as the camera. We normally employed a soft front light placed at a very slight side angle. For further direction of the light, we used either a Chimera softbox fitted with a honeycomb grid, or Chimera Chinese lanterns. We had three or four Chinese lanterns of different sizes; they work well if one can get the right low angle.

"We also used a small Dedo eye light on a dimmer above the lens for Kim," he adds. "I always keep my eye light a half-inch or so off the axis of the lens, on the side away from the key light. The Dedo eliminates small skin problems and adds brilliance to the face and eyes. We also used a low-angle reflector and occasionally a very light Mitchell filter on the lens. Of course, the fact that we were shooting in Super 35, with its additional resolution-reducing optical step, kept our need for lens diffusion to a minimum."

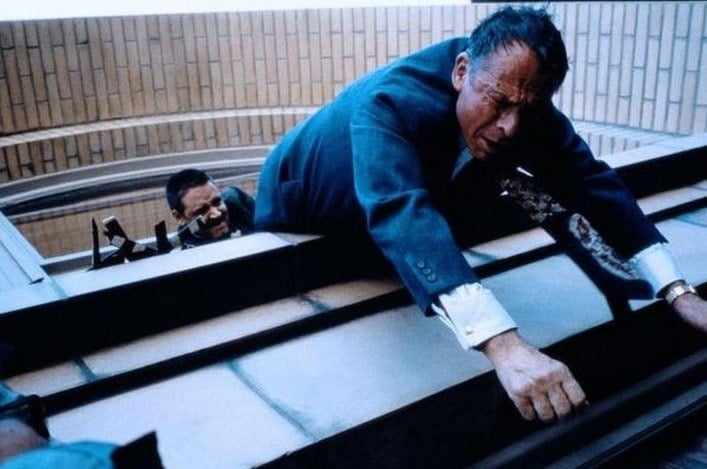

views of Officer

White dangling crooked D.A.

Ellis Lowe (Ron

Rifkin) from a ledge

to coerce a

confession about

the LAPD's role in

the Mafia drug

trade.

Hanson notes that Spinotti also made extensive use of reflections. The director recalls, "The key moment for Vincennes occurs when he has taken $100 from Hudgeons [after setting up a district attorney in a homosexual situation, with tragic results]. Sitting in a bar, Vincennes looks in the mirror and is filled with self-loathing. In previous sequences, we had seen him checking himself out in mirrors, and in effect responding, 'Aren't I cool?' Dante skillfully used reflections to help emphasize the dualities that run throughout the story from beginning to end, without drawing attention to the technique in what could have been a distracting way.

"Key scenes that occur in a police interrogation room employed a clever use of one-way mirrors to keep both sides of the story planted firmly in the viewer's mind. Says Spinotti of this setup, "We took a one-way mirror and positioned the reflecting side so that it faced the room in which the cops were observing the suspects. That allowed me to create a strong, detailed double image; the image in the glass is the reverse of real-life, and you can clearly see the corrupt cops' complicated reactions to the interrogations. You are also able to see the suspects because they are strongly lit by a single practical bulb that hangs very close to their faces."

Another unusual touch for a period piece such as L.A. Confidential is the cinematographer's liberal use of fluorescent fixtures. Hanson notes, "The story is set in 1953, not the Forties, so while fluorescents had not yet taken over, they were in use. Fluorescents helped us underline a key theme, that of the new world rolling over the old Los Angeles, a place that had been so unique. Many things that are so commonplace now — such as glaring fluorescent lights, tabloid journalism, the suburbs, and television — were all new in the early 1950s”

Most scenes in the film's police headquarters have a moderate greenish tinge from the strong overhead fluorescent practicals. Fluorescents were also used to create a subtle effect during a crucial speech delivered by Exley, in which he denotes his deeply personal reasons for joining the police force. The scene is staged in an old-fashioned homicide squad room. Behind Exley lies a large open area bathed in greenish fluorescent lights; their presence is further emphasized by the low-angled, long-lens perspective of the camera. Exley is tightly framed by the fluorescents, which are several stops over the scene's exposure. This striking tableau effectively highlights the less attractive — but imminent and highly efficient — wavelength of the future, thus bolstering one of Hanson's key themes.

Spinotti's naturalistic approach is carried to a powerful extreme in a climactic scene during which White and Exley are ambushed by some scoundrels, who subsequently trap them in a room at an old motel. "To defend themselves, they close all the doors and windows so the shooters won't know where they are in the room," says the cameraman. "Our key light for this interior scene was a 20K on a Condor way out in front of the motel. We let it go very dark in that room. This was one of the rare times I extensively underexposed [the scene] by as much as one to two stops. Sometimes I would include some brightness in the scene, but that was kept to a minimum. It turned out to be a nice exercise, because a good deal of the action happens in shadow; you can barely see the faces or the action, but it works."

The 20K key light was supplemented, but only in a minor and motivated manner. "We did place a 10K outside near the back window of the room; it was justified by a streetlamp that we placed with the production designer."

The addition of dust to this sequence, ostensibly generated by a barrage of bullets that breaks up the old wooden walls, helped add some definition to shafts of light filtering into the room from the 20K outside. The large exterior key source was also slightly augmented inside the room with a 500- watt Dedo bounced off of a Rosco screen. "When the walls and windows are broken by the gunfire, more light from the 20K comes into the room, and you start to see more detail," Spinotti notes. "On the exterior, we kept the big key light low so we had a dramatic shadow-line halfway up the walls. When the main bad guys finally come into the room, the top portion of his body is in deep shadow."

The dark color palette of L.A. Confidential may receive some enhancement from the use of Technicolor's ENR process. Spinotti explains, "While the film was not shot for an ENR release, I kept in the back of my mind that it was a possibility. We tested the process for L.A. Confidential, and it was extremely successful, so we are hoping that 100 or more of the prints will receive a light ENR treatment. "ENR is a very interesting process which adds sharpness and depth to the blacks, as well as an elegant, three-dimensional quality overall; your tones pick up energy. If we do get these 100 or so ENR prints, the effect will not be too overly dramatic. In the case of L.A. Confidential, ENR would be used simply to help us get a better print. But the process is expensive and takes time, so sometimes it doesn't get done even when it's planned."

Spinotti says that he is impressed with Kodak's Vision 500T 5279 high-speed stock, but still opted to use the 200 ASA 5293 as often as possible on L.A. Confidential. "I tried to use 93 whenever I could," he says. "Its beauty is hard to surpass. The richness of 93's blacks and skin tones, and the quality of the colors, is wonderful. When an actor goes from light to shadow and back, the color doesn't change as the exposure goes up and down the curve. The 79 was impressive; it held the highlights and has fine grain, which was very good for Super 35. However, 93 still has an edge with its rich blacks. On L.A. Confidential, we ended up shooting approximately 60 percent of the film with 5279 and 40 percent with 5293." Spinotti tends to under¬ rate his respective stocks. "I like strong blacks and contrast, so I usually expose [5279] at 400 ASA," he explains. "I'll go as high as 500 occasionally, as I have found that the 79 is more sensitive than the old 5298.1 also overexpose when I use 5293, unless I have a very high-key scene; I'm usually rating it at about 160, but it varies."

The cinematographer's drive for contrast is further enhanced by his choice of labs. He prefers to print at Technicolor Los Angeles, "with a 34-35 light on the average. To get the same results at other labs, they have to print in the low 40's. Technicolor L.A. just produces more contrast, which I have found that I like; the colors are right there, big and bright."

For stylistic and practical reasons, wide angles prevailed on L.A. Confidential. Spinotti says that this tendency was "part of our plan to achieve a still-photo look. We used a lot of wide Panavision primes, such as the 21mm T2.8 MKII, but nothing wider. The primes were mostly used for night interiors and exteriors, because we needed lenses we could open up.

"We used the Panavision short and super Primo zooms, the 17.5-75mm T2.3 and the 24mm275mm T2.8, both of which work very well. We also used some long lenses. We had great cooperation from Panavision Tarzana, as we have come to expect."

Spinotti's A-camera was a Platinum Panaflex; a Lightweight Panaflex was used with the Steadicam (deftly operated by Jimmy Muro) and a Golden Panaflex served as the show's B-camera. Gary Jay was the A-camera operator, while Peter Gulla operated the B-camera and Dwayne Manwiller served as the "magic focus-puller."

While the Italian-born Spinotti acknowledges the fine work being done by crews in his native land, he says that he has developed a great regard for American camera teams and enjoys working on stateside productions. "These Hollywood crews always amaze me with their ability to cope with problems," he attests. "You get a lot more freedom working with a crew of this caliber. I know I can shoot actors walking toward the camera with a 300mm lens wide open at f2.8 and stay in focus. Of course, there may be one take where the actors are a little soft, but the assistant cameraman has invariably warned the script supervisor, so any unpleasant surprises are very rare!"

Among other honors, the cinematographer earned Academy and ASC Award nominations for his expert camerawork, and was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2012.