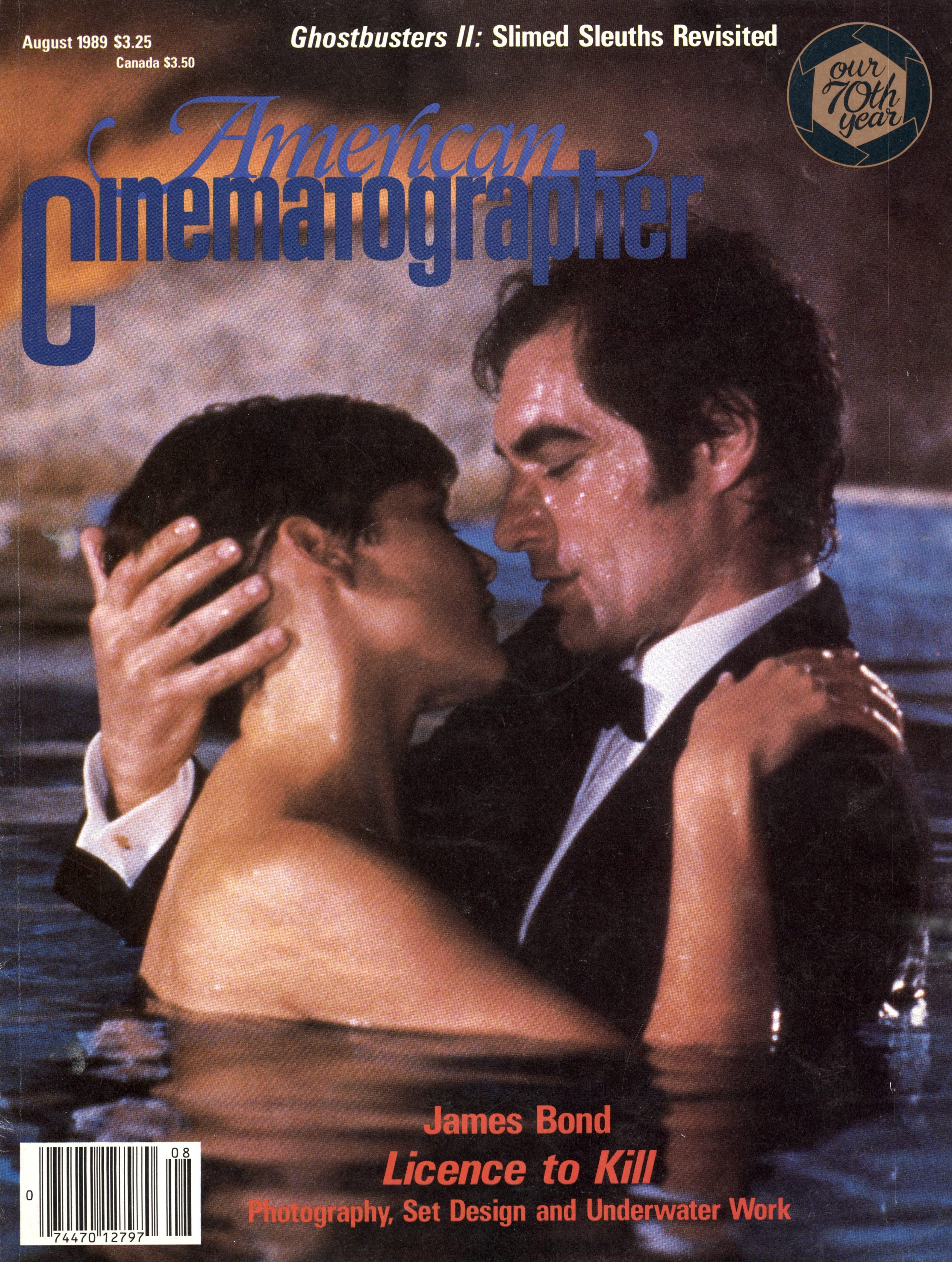

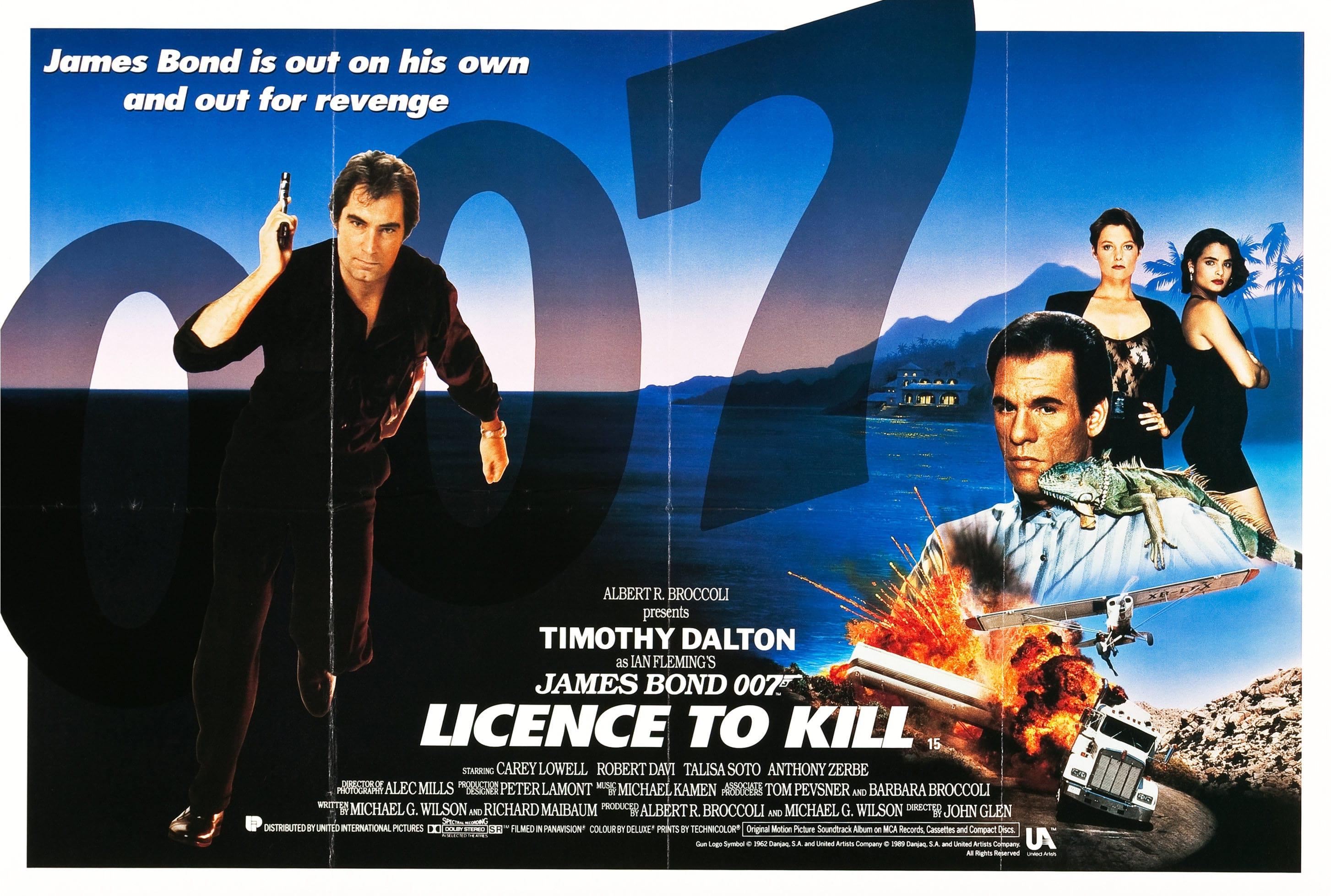

Licence To Kill — No. 16 and Counting

Cinematographer Alec Mills, BSC returns to the James Bond franchise for yet another mission behind the camera.

Some argue that he is past his prime. Others say that there are no stories left to tell. Still, others insist he's become a fool, a joke. But it's just like him to ignore the odds. It's just like him to gamble again with his life as the stakes. He knows the allure of adventure and intrigue. His loyal followers, which number over a billion, would expect no less. So, for the 16th time, James Bond is back and he certainly hasn't lost his edge

In fact, Licence to Kill is part of a continuing attempt by writer-producer Michael Wilson and cohorts to return Bond to the hard-edged adventuring hero of the original Fleming stories. The decision was made to go in this direction when Welshman Timothy Dalton became the fourth actor to play James Bond by starring in The Living Daylights.

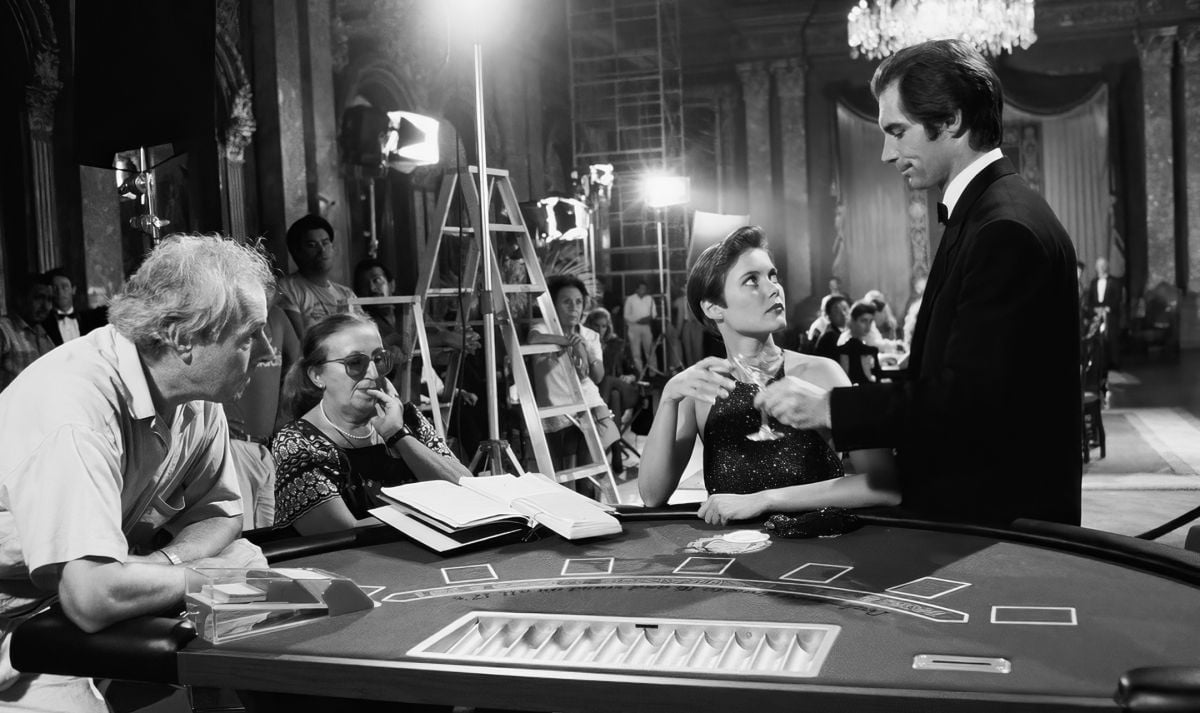

This time, to revenge a longtime friend (David Hedison) and his wife (Priscilla Barnes), Bond goes against direct orders from M and sets off on his own mission. He faces a villain taken from the front page of today's newspaper. Robert Davi plays Franz Sanchez, a South American-styled drug lord who is aided by a cunning marine biologist Milton Krest (Anthony Zerbe) and the perfectly slimy Joe Butcher (Wayne Newton), a televangelist promoting cone power. There are the requisite beautiful Bond girls. The good girl (Carey Lowell) is a pilot and a DEA agent, and the good bad girl (Talisa Soto) simply can't resist the charms of the suave Bond. Perhaps the most telling aspect of this new story is that the working title was Licence Revoked.

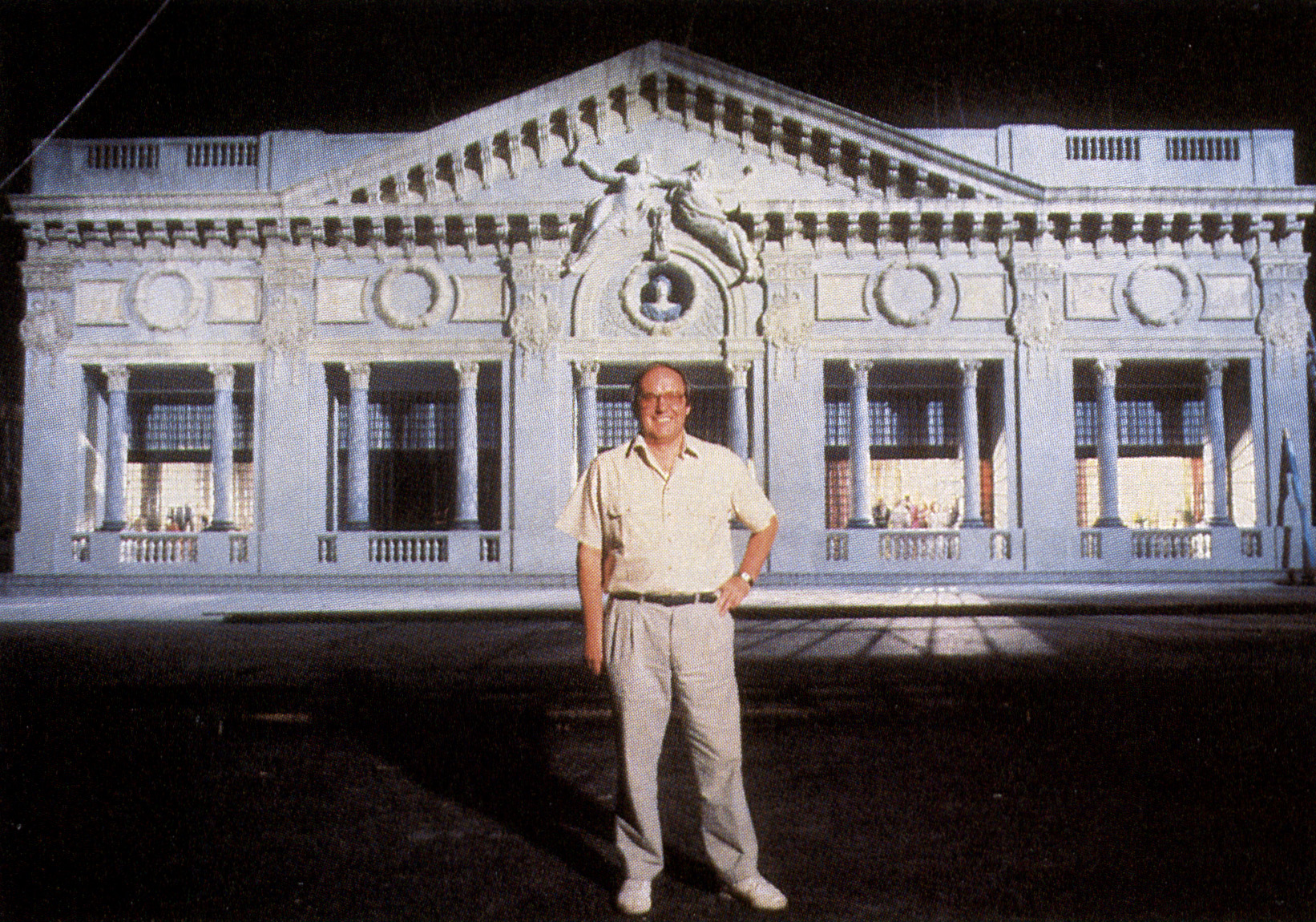

Over the last 27 years, the ever-constant English camera crews have faced untold dangers in exotic locations, much like their fictional hero. But with the exception of Moonraker (filmed in studios near Paris), they have been able to return to the welcoming arms of Pinewood Studios to build their sets and explode their miniatures. Not this time. This time, in an attempt to keep the cost of the Bond picture the same as it was two years ago (an estimated $35 million) almost the entire film was made on location in Mexico and at Mexico City's Churubusco Studio. The only exotic locale was the Florida Keys. Some key crew members were in Mexico for more than six months and by mid-October, many of them were longing for a really good cup of tea. Shooting such a large and normally well-oiled production in a strange place was perhaps the biggest challenge on the newest Bond.

Alec Mills, BSC, was completing work on this, his seventh Bond (his second as director of photography), and was in the midst of lighting the huge set of a cocaine processing plant when he began the saga of Bond in Mexico. Working with a Mexican crew presented some cultural challenges, he acknowledged. Language, of course, was an obvious problem. But there were other small things that occasionally caused glitches.

Mills tells the story of asking the Mexican clapper boy to get the camera crew some tea, because everyone else was busy: "He resented that, I think. Whereas, if it were the other way around, one of our boys wouldn't have minded at all getting tea for him. I'm not criticizing, I'm only pointing out some of the cultural differences we had to deal with." Mills had no way of knowing he would offend the clapper boy and he only offered the story by way of illustration.

Mills knows he was fortunate to be able to bring his camera crew, and gaffer. "Those are the two things that affect me most as director of photography," he explained. "And I can tell you from my experience on this film, I couldn't have done it any other way. Any time you are working with someone new or someone who doesn't speak your language, it's difficult. They could be the best in the business, but I would always have to have one eye open to make sure they were doing what I wanted or needed. That extra bit of worry takes me away from what I should be thinking about. Thank goodness for people like Michael Frith, Frank Elliott, Simon Mills, Chunky Huse, and my gaffer, John Tythe. They take a lot of the pressure off me..."

In an interesting aside, Mills revealed, "John Tythe has retired. I drag him out for Bond. Oh, he does the odd thing here and there, but he doesn't do commercials. I carry on without John, obviously — until the next Bond. But if he fancies it, I'll always give John the opportunity to do Bond, because he knows the way I work."

Tythe has worked on every Bond film Cubby Broccoli has produced. His first film was the definitive Oliver Twist, directed by David Lean in 1948. "John can be a little bull-nosed about some things. He has no time for cinematographers who don't light things the way he likes to see them lit," said Mills, with a knowing laugh. "Underneath it all, he's a first-class gaffer."

It was necessary to fill out the crew with local Mexican craftsman. Many belong to local unions or guilds and some have been with the studios for a long time. Churubusco, by the way, was originally built in the ’40s by RKO. Unfortunately, due to the ever-changing political climate in Mexico, the facility has not been maintained as well as it should. As a result, the production company was plagued by a host of small technical problems that were unexpected.

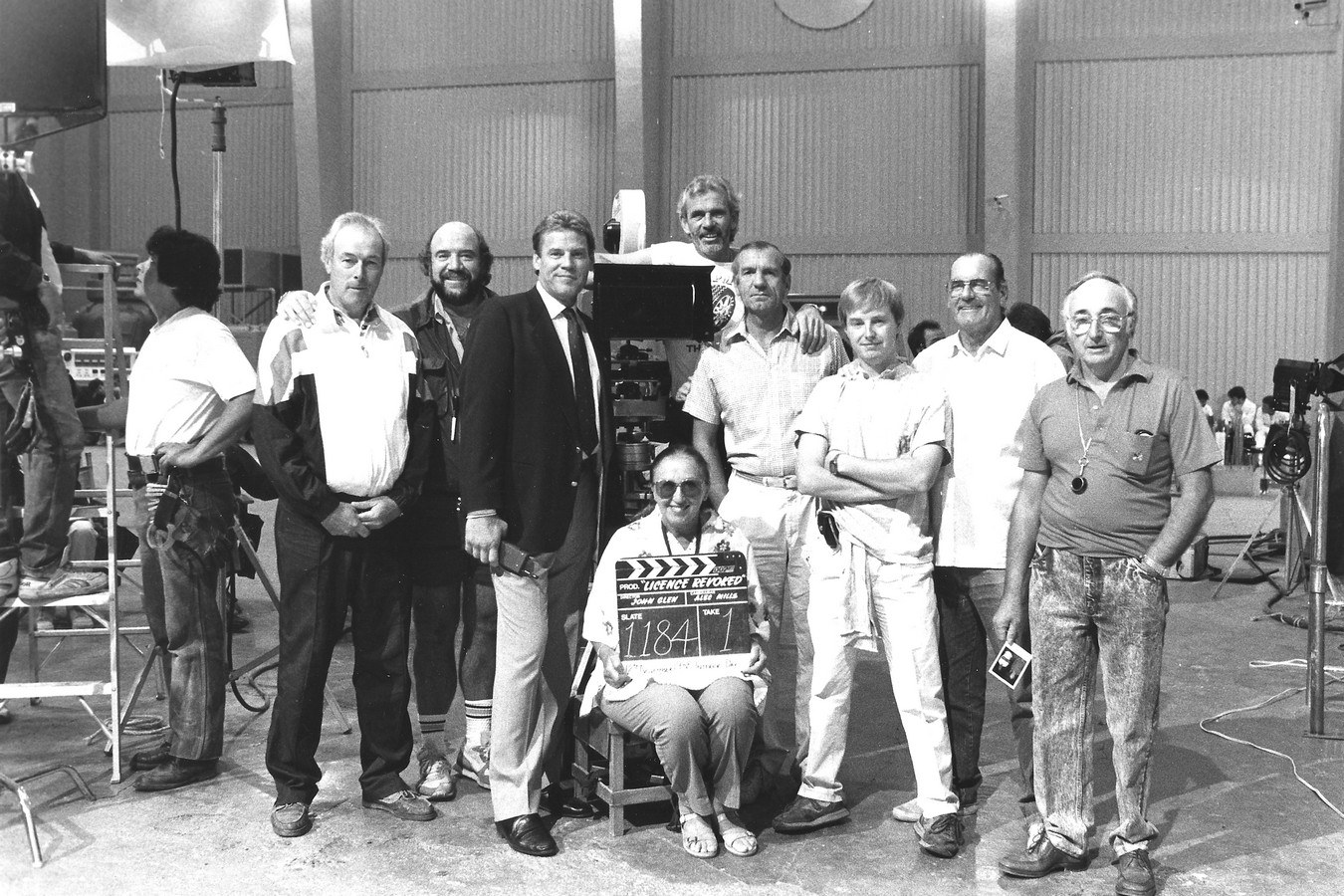

Mills, venerable gaffer John Tithe, actors Robert Davi and Timothy Dalton (seated), Mills, script supervisor June

Randall and director John Glen.

One immediate adjustment that had to made was in the organization of the crew. Mills described one of the differences: "The English grip system is quite different from the Mexican grip system. In England, our grip, Chunky Huse, moves the dolly. In Mexico, and in America, you have a key grip who supervises several grips that not only move dollies but flag the lights and things. When Chunky works here in Mexico, he works the key system."

Besides the crew working on the set with Mills, he recruited a rigging crew, normally headed up by Tythe, to "help keep us on schedule. As you can see, coming on to a set like this [the huge cocaine processing plant], it would take us about four hours to rig it with lights and that's if everyone is ready and standing by.

“With a pre-rigging crew, I should be able to knock it down to two, more likely three, but if I could do it in two I would be the hero,” Mills added with an ever-present twinkle in his eye.

By mid-October, lines of communication with the crew were pretty well established. They had been working together since mid-July. But Mills recounted a tale from early in the shoot that explained why he continued to keep his "one eye open." On one of the stages, production designer Peter Lamont and his crew had constructed what the English call a composite set. It was both an exterior and interior set. This particular one was very large and built to match an existing building in Mexico City. Once finished, Mills began the job of lighting it.

"This set required about four or five rooms to be lit plus the exterior,” the cinematographer described. “I lit the exterior first, making sure I was matching the stuff we did to our outside location, then I did all the interiors. I began in the first room where a couple of people would be talking. In the next room, there was a bigger meeting and I lit that with different colored gels to try and give it the sense of a business-like room. In the next room, there was to be a party going on with beautiful girls all over the place. That went on into another room which was unoccupied.

"I found that when I got to the last room, the electricians had been pinching lights from the first rooms I had lit! That set us back a little bit," he said with considerable understatement. "It was a lack of understanding, not a lack of lights because we did the whole set eventually It was a case of '‘can I have a 2K here’ and the electricians would all rush to grab one and I would be presented with three 2Ks and I only needed one. But that's the credit side, you see. They were trying to be helpful. It was a classic case of more haste, less speed."

The little problems continued, though and they included things that Mills found inexplicable. "For instance, at the end of the day, I would say, 'We're through for the day. That's it, cut! Don't move anything, we'll be back here tomorrow.' The next day, we'd come in and the lamps had been moved. It's not a big thing really, but it all adds to the lighting cameraman's frustration when trying to keep to a schedule."

Another continuing frustration was electrical power. It proved undependable and even dangerous. Electrical fires on the set were not uncommon: "One of the first things we discovered when we came here is that we had to keep a regular check on the power — it goes up and down.

"The cabling system here is very antiquated. The wires are thin — almost like shaver plugs. It's very easy for someone to kick them out, so every light requires your undivided attention. And they often are very dangerous. You've got to have eyes in the back of your head.

“On many, many occasions we had electrical breakdowns [power outages]. Especially at the beginning of the picture. It wouldn't be an exaggeration to say that in a day we would have four or five breakdowns. In this business that gets very expensive. Time is money. It puts pressure on the director and on the cinematographer.”

“Our greatest hope is that when we get to the end of the day we're still reasonably on schedule,” Mills continued. “So far we've been able to do it, even with all these problems. But we had to bring in our own generators and even they burn! We've had two or three fires on them. We've had a series of bad runs. Every cinematographer and every director has their problems, though. All the departments have had it very tough, probably much tougher than me. But the result is it often takes about one-and-half day's work to do what we normally do in one. It may sound like an exaggeration, but it's not."

Still another problem was dailies — or rushes, as Mills calls them. "We've had a lot of good rushes. But I must admit I've been spoiled by the labs at home. They always grade my rushes [color correct them] and in the States you have the one-light system. We've used Deluxe in L.A. and Dash Morrison and the lads have been really wonderful. But the worst thing for me is the projection here. They just can't get enough light behind it. I've seen rushes and come out so depressed... because of the depressing state I'd find myself in after rushes, I quit going.

"I wouldn't want everyone to think making this film was a depressing state — it's not. And I wouldn't want to put anyone off filming in Mexico. It can be wonderful, and if I was asked to come again I would."

One thing that was not a problem was camera and lighting equipment — cranes excepted. The studio has its own supply of new Desisti lights and others were available from the rental houses. The Panavision camera was brought in from Los Angeles and the second unit was an Arriflex. While Mills admits that it was a bit scary to not have a backup A-camera right at hand, he also said, "Amazing isn't it, that it's worked out, But it has and we've saved money."

Saving money was of course, the reason for doing the film in Mexico in the first place. Writer-producer Michael Wilson was very candid when asked about the budget. The company calculations showed that they could save about $5 million by shooting in Mexico. Apparently, Danjaq's expectations were more than exceeded. Somehow the idea of saving money was instilled in the crew all the way down the ranks. It became almost a matter of pride.

“We've all got a responsibility to get the best deal we can for the company and to cut corners occasionally. The cameraman and the gaffer have a responsibility. The old-fashioned days when you could have anything you want are gone. We've all grown up now and we've got to be responsible, so I'm very careful," said Mills.

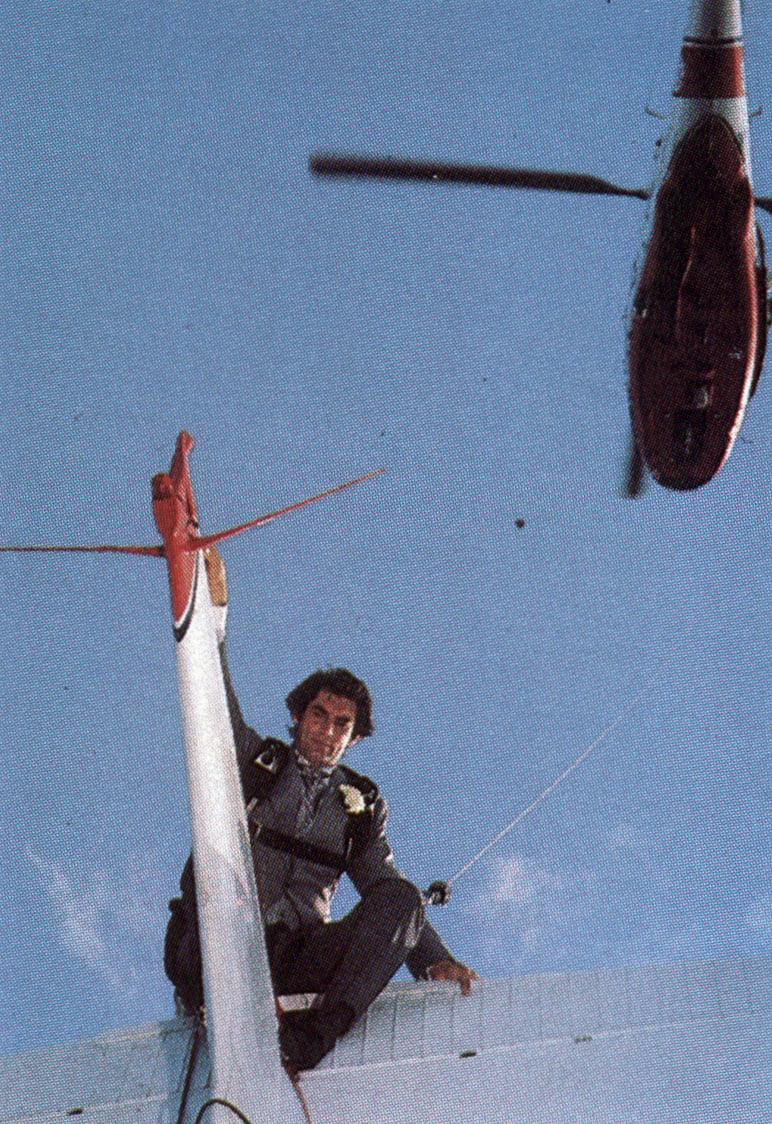

The second camera was also used for hand-held shots, something that almost seems out of place in a slick Bond film. According to camera operator Michael Frift, this Bond has quite a bit of hand-held camera work. But Mills doesn't see it as an unusual amount. ''I've operated on five Bonds and I would say that, on the average, about a tenth of each one is hand-held. We use it for fights mainly. I remember being so tired at the end of the days we did fights. That camera can be quite a weight. And if you have three days of fight scenes... well...''

Undoubtedly it was the weight of that Arri that stuck in Frift's mind.

when Dalton did some of his own

stunts. Note his

morning coat

complete with

boutonniere and

parachute.

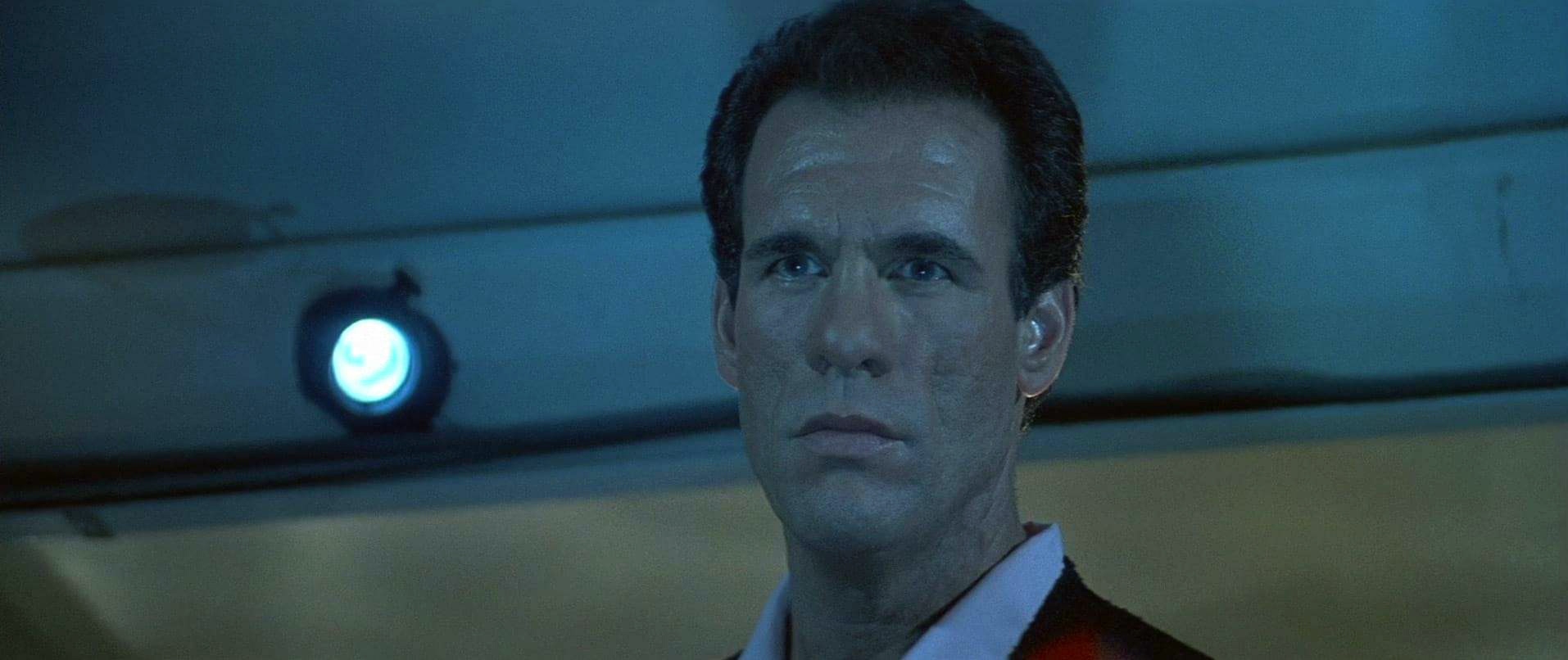

Technical and labor problems aside, Mills and director John Glen have opted to continue the “Boys Own" lighting style Mills re-established in the last Bond. “I wouldn't change a thing," he said and he went on to explain why: “There is a Bond look. It's the idea of a little splash of color here and there. Again I've used nothing on the camera. Instead, I put colored filters [gels] on the lights — that's the Bond trademark. This processing plant set will be full of red light, for example. The facility is supposed to be underground except for the helicopter pad, so when Bond leaves the helicopter pad he goes through a tunnel of red light and comes out here. This is a continuation of the red area. When you stand back and look at this room, it's basically grey. You need the color.

"The source lighting is established by the lights around the wall and they are all white lights, but I will pull the color in where I can. Down near those storage tanks for instance," Mills continued. "And up here in the laboratory, I'll have colored water in all these chemical bottles — a little bit of red here, too — sort of Frankensteinish. The more color that you can inject, the better. I'll probably put a red light around the air filtering system to make it look dangerous."

One exciting sequence was shot in an unusual house in Acapulco. The home of an Italian nobleman, the house couldn't have been more perfect if it had been designed for a Bond film. The predominant color is white. There is a patio filled with life-sized sculptures of white camels and an unbelievable dining room with a glass table balanced on the back of a camel sculpture. But was it harder to light?

"It wasn't harder to light, I can't say that really. Nothing is hard if you have enough time. Of course, there are differences. My lights on this processing plant set are 50 feet in the air. In someone's house, everything has to come down. Here I can't do the kind of molding I like. We try to get some shadow areas and do our best, but this warehouse isn't supposed to look beautiful. That dining room was. And for me, the great compliment was the Baroness who owns the home has been trying to get that same golden tone in her own lighting of the room and she can't get it. I was lucky. All I had to do was put some filters on the lamps and we're away.

"The challenge was white-on-white. Sometimes I've said to Peter [Lamont], 'When are you going to get past this white phase in your life? You've got to get it out of your system on this film — everything is white or light grey!' It's interesting, when you've got white, you have to try to keep light off the set."

Mills' collaboration with Lamont is well-documented, but he also has to work with the costumer, in this case, Jodie Tillen. She, too, picked up on the "splash of color" idea and the best example is Soto's villainous red dress in the casino sequence. Occasionally Mills admits he's been surprised. "There were times when I would get a bit of a shock — like a night exterior and someone shows up in a beautiful white dress. If I'm not careful, she winds up looking like a ghost. But Jodie is really very good. Maybe the best thing is we all stick up for what we believe. I won't give in to Jodie too much and she won't give in to me. We all have our opinions and that's good. If we were all 'yes men' to one another we'd have a pretty dismal film. That's probably one of the things that makes the Bond films good.

"All of us are under pressure from all sides. At the end of the day, if it all comes out on the screen, then we can sit back and think what good jobs we did — even if we did have a bit of a tiff to get it done."

But without fail, they do get it done. Five crews working all over Mexico, a Mexican second-unit crew doing inserts, hundreds of people to coordinate, miniatures to build, exploding trucks to rig, sharks to catch, and, unbelievably, all of it comes together. No wonder Mills can honestly say, "If you're associated with Bond, it's something to be proud of."

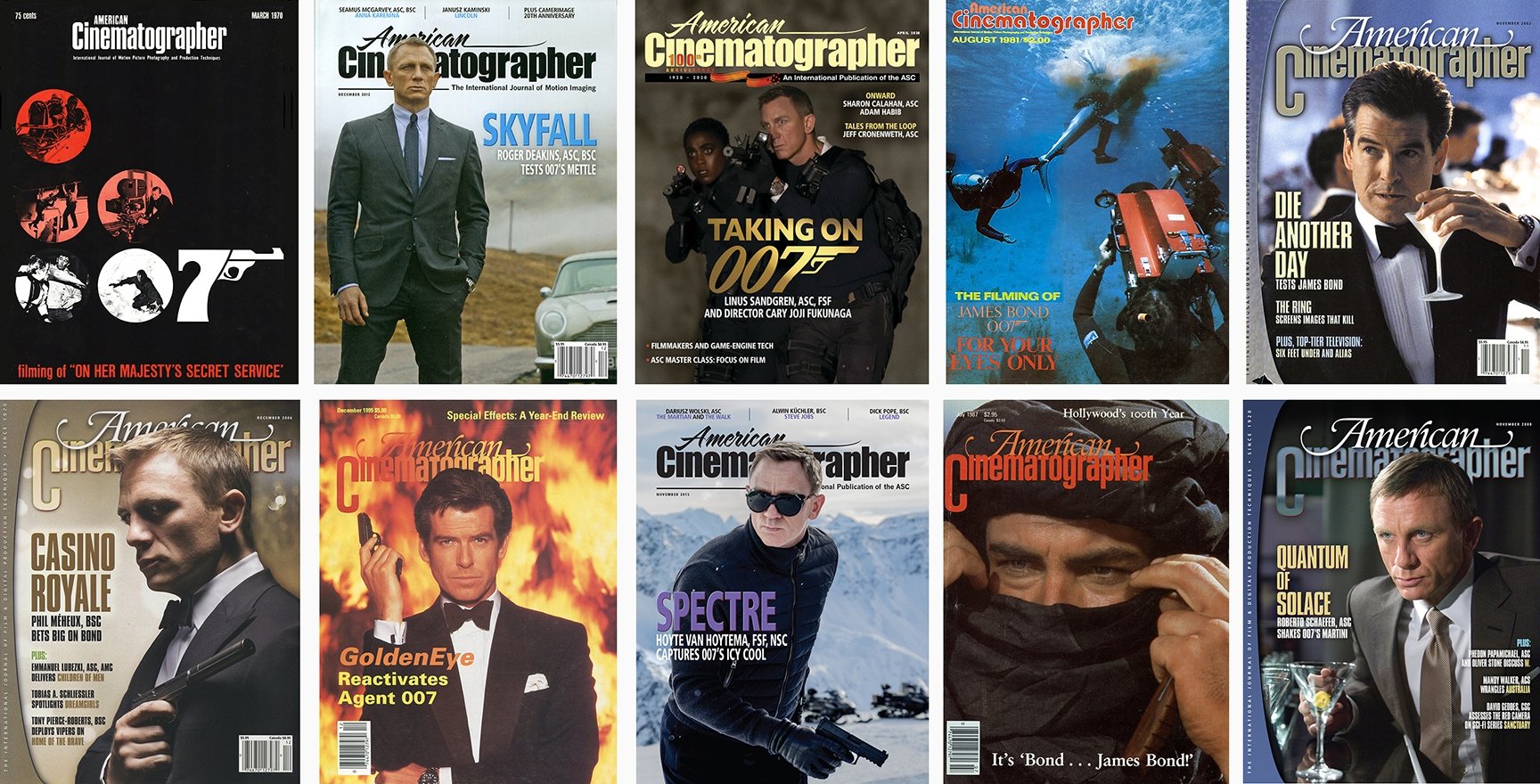

You’ll find more of AC’s 007 coverage

from our archives here.

For access to all 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.