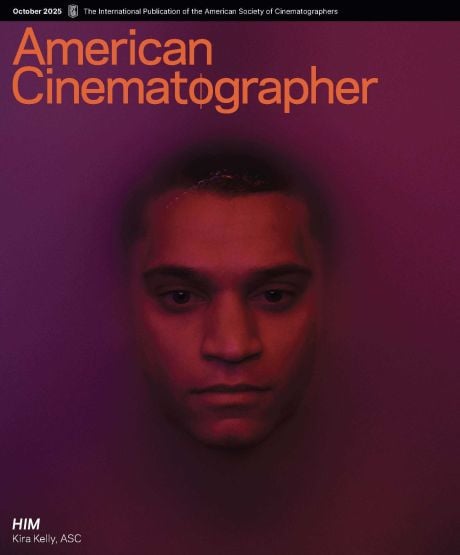

The Life of Chuck: Crafting a Coming-of-Age Story in Reverse

For his first collaboration with director Mike Flanagan, Eben Bolter, ASC, BSC chose a multitude of lenses and colors to tell a remarkable life story that begins in adulthood and ends in childhood.

While the name "Stephen King" may first bring to mind dark towers, haunted hotels, and killer clowns, horror's most prolific author has amassed an impressive body of non-horror fiction, including novellas like "The Body" (adapted into the film Stand By Me, photographed by Thomas Del Ruth, ASC), "Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption", (adapted into the film The Shawshank Redemption, photographed by Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC), and "The Life of Chuck," recently adapted into the film directed by Mike Flanagan (Gerald's Game, Doctor Sleep) and shot by Eben Bolter, ASC, BSC.

The Life of Chuck tells a "reverse narrative" about Chuck Krantz (Tom Hiddleston), a middle-aged accountant who danced his way through life before it was cut short by a fatal brain tumor. The opening act sees the world crumbling around a group of imaginary (or are they?) people living in Chuck's mind as his consciousness slips away. The second act is a day in the life of Chuck before his illness sets in, when he finds himself inspired by the performance of a street drummer (Taylor Gordon) to break into a medley of solo dances before drawing in a thrilled bystander (Annalise Basso). The last act follows young Chuck through a series of losses, starting with that of his parents. Chuck's grandmother (Mia Sara) and grandfather (Mark Hamill) introduce Chuck to the wonders of Hollywood musicals, but keep a terrible mystery locked away in the top floor of their home.

Bolter's previous work includes more than a dozen feature films, as well as episodes for such high-end television series as Avenue 5, The Girl Before, and the first season of The Last of Us. This is first collaboration with Flanagan.

Here, Bolter outlines the way he used different lenses, aspect ratios, and color grades for the different acts in The Life of Chuck, as well as his and Flanagan's approach to filming the second act's memorable dance medley. — Iain Marcks

Three Acts, Three Looks

The film is in three acts, with three distinct looks — three LUTs, three lenses and three aspect ratios. There's a line in the story about the narrowing of Chuck's world, so Mike Flanagan and I were talking about how we could communicate that visually. We landed on the idea that if we started with a 2.39:1 aspect ratio, then went to 2:1 and ended with 1.85, the effect would be like seeing a movie in the cinema — where the curtains draw inward, narrowing the width of the screen for a non-anamorphic image. (This works differently on a 16:9 television, where the 2:1 and 1.85 aspect ratios would come out taller, with the same width as 2.39.)

For Act Three, which comes at the beginning of the film, 2.39 was the best way to present our high-concept apocalypse in Chuck’s imagination. His multitudes are expressed as a Hollywood fever dream as he dies, so I wanted to lean into that: widescreen anamorphic, shallow focus and a modern "Hollywood look," with more teal and orange. The starting point for the Act Three LUT was a modern Kodak 5219 emulation.

Chuck's dance in Act Two marks the midpoint of our story. For this segment, we used a Technicolor film emulation we built with [ASC Associate Member] Jill Bogdanowicz at Company 3, inspired by West Side Story, a bit of Singin’ in the Rain and a bit of The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. Here, we thought the idea of a head-to-toe shot of two people holding hands felt nice in a 2:1 aspect ratio.

Act One is the end of our story, about Chuck and his early life. We thought that the 1.85 ratio was a bit more grounded, a bit more about people. Here, I used spherical lenses, and looked at some of Stephen King’s earlier adaptations, like Stand by Me and The Shawshank Redemption, and tried to tap into the lighting, the aspect ratio — both are 1.85 — and the visual language of those films.

Different Looks, Different Lenses

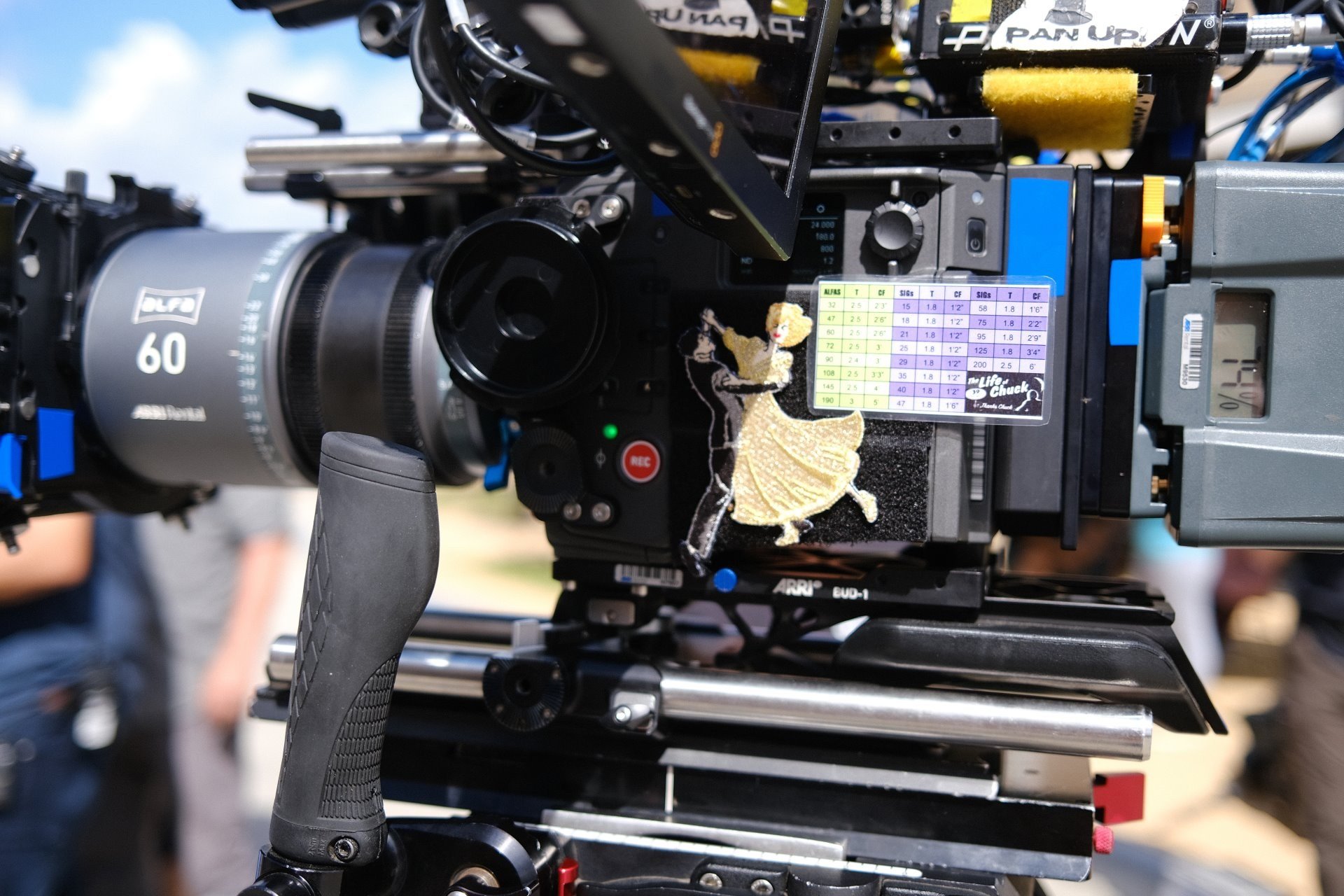

This is not a big studio movie, but Arri Rental London and New York worked with us to meet our ambitions, for which I have so much gratitude. We used an Alexa 35 in Open Gate mode, and I ended up choosing the Arri Alfa anamorphics for Act Three and Act Two. For Act One, we went spherical. This is where I was the most surprised with what I picked, because I'm predisposed to shoot with Cooke or the Arri DNA lenses. But I did a truly blind taste test, and I kept coming back to the Arri Signature Primes, which are a very modern-looking lenses; we used their Impression Filters, which go behind the lens and allow you to add varying degrees of distortion to the edges of the image. I liked the +2 and +3 Impression Filters, which gave me a very clean, contrasty image in the middle of the lens that deteriorated towards the edges, but it was controllable. I really leaned into that for the prom sequence in Act One and exaggerated the dreaminess of the frame edges, while in other moments, I could make the image sharp edge to edge with the same lens.

The Dance of Life

We always knew that dance was going to be this big centerpiece of the movie, and it had to be, in visual terms, a real celebration of what it is to be alive. We knew it was going to be about six minutes long, with different dancing styles. And it was shot on location — at an amusement park in Fairhope, Alabama, on one of the main streets there, which had an unspecific but classic American feel — so a lot of our planning conversations were about where the sun would be at different times of day.

Before that, Mike and I broke down the whole script into what was probably the most detailed shot list I've ever done. But we left the dance until last because we wanted to indulge in a couple of days of watching the progression of dance throughout the cinema. We watched Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers movies, Singin’ in the Rain, Bob Fosse and All That Jazz, all the way up to La La Land and “Weapon of Choice,” the Fat Boy Slim music video. We studied how people shoot dance, what works for us, and what we could add to it.

We learned that the most effective way to film a dance is to show somebody head to toe. A dance is a full-body thing: The audience needs to see feet, arms and movement. It's incredible how many of the great dance numbers in cinema history are shot from waist height or lower — ever so slightly looking up, framing the actors head to toe in a master shot. The shot will jump in for mid shots or medium close-ups, but then it'll jump straight back out pretty quickly. It gives that feeling of sitting in a theater, looking slightly up at a dancer onstage.

Meanwhile, the actors are rehearsing their dance, and I would use the Artemis Pro app on my iPhone to look at different angles, and added those to our shot list.

The most important shot for the dance was the head-to-toe classic shot. We shot the whole number on a crane, sweeping slowly from left to right, in a single six-and-a-half-minute take. It was brilliant. We could’ve used that shot without a single edit, which would’ve been very impressive, in a technical sense, but Mike wanted the ability to cut whenever he felt he needed to — to the drummer, to the girl in the crowd, to Chuck. There's a lot of storytelling in Tom's face that you’d miss in a wide shot, and part of my job was to be as consistent as possible, so that no matter what, Mike — who also edited the film — had a shot that worked.

Once we had our plan for how we were going to shoot the dance, we started to schedule that around the sun position. We had four sunrises, four daytimes, four magic hours and four nights. We wanted the dancers backlit and side-lit as much as possible, and there was a sweet spot for the sun to shoot our major coverage and major dancing shots, so we scheduled our day to make that work. For the first hour of the day, when the sun hasn't quite popped over the buildings, we would film Chuck ordering coffee or walking down the street, then we’d pivot to the dance and shoot up the street. Middle of the day, we’d do our main dancing shots. At the end of the day, we’d look down the street. That’s also when we shot the conversation at the table by the water, the goodbyes, and Chuck’s walk home alone. I did have some 18Ks on stands and a couple hidden on rooftops that enabled me to fill things in if I needed to, but we weren’t strict about anything. There are certain times when the sun position and the lighting are less important than the spontaneity of a moment.