An Artful Apocalypse for The Last of Us

Four cinematographers help transform the frightful video game into a hit horror series.

All images courtesy of HBO Max

A video game does not have to tell a good story to succeed, but a television series based on a game must tell a good story, or else. And when a game that serves as the source material for a series features a story that’s near-unanimously praised by gamers and non-gamers alike, the filmmakers behind the TV adaptation are under even more pressure to deliver an experience that both transcends gameplay and provides an equally compelling narrative.

“The Last of Us is not only a story about surviving the post-apocalyptic world; it’s about surviving emotional loss and learning to build again,” says cinematographer Ksenia Sereda, RGC, who photographed the pilot for the HBO Max series — based on the Naughty Dog/Sony video game of the same name co-created by Neil Druckmann and Bruce Straley. She also shot Episodes 2 and 7.

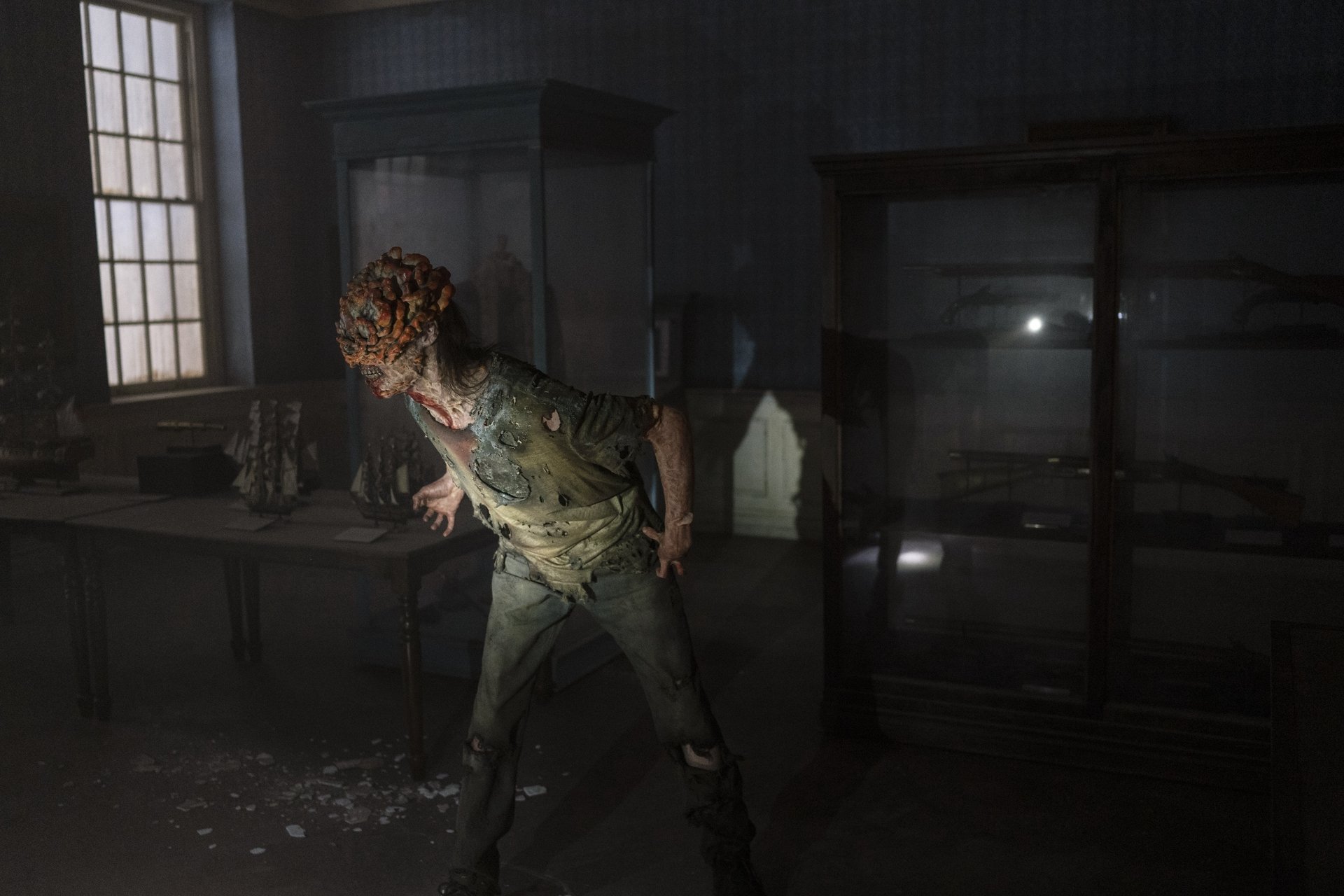

Sereda’s work introduces viewers to grizzled smuggler Joel (Pedro Pascal) and 14-year-old Ellie (Bella Ramsey) as they make their way from Boston to Salt Lake City, carrying with them the hope of ending an apocalyptic outbreak of mutant fungus that infects the minds and bodies of nearly all of humanity. Along the way, the “infected” and warring factions of survivors pose equal threats to Joel and Ellie’s success.

At the helm of this game-to-screen adaptation is showrunner Craig Mazin — also the creator of HBO’s Chernobyl — who counts himself among the game’s admirers and sought to further explore its story and setting in the TV format. “The thing I loved about the game is that it has this beautiful, grounded visual tone,” says Mazin, who directed the pilot episode. “For the show, what Neil [co-writer/co-creator and a director on the series] wanted in terms of visual tone was Chernobyl, which has a vibe I love: as realistic as possible, allowing for handheld, so you feel like you’re there; finding the beauty in the ugly; and trying to get to the truth without it feeling over-engineered — which is a tricky thing when everything is constructed, designed and calculated.”

The Last of Us uses its nine-episode first season to flesh out character details and plot points — while photographically, the series owes much to the game’s dystopian setting and its moody, naturalistic lighting. Because the story unfolds over a year’s time, changing seasons also come into play.

“In terms of colors, the world of the show is faded — the sun has washed everything out.”

— showrunner Craig Mazin

Primary Objectives

“The Last of Us has a constrained palette, with daylight, moonlight and firelight doing a lot of the heavy lifting,” says Eben Bolter, BSC, another of the four cinematographers on the series, which was photographed on stages and locations around Calgary and in the wilds of Alberta, Canada. “We grounded everything in firm reality — lighting through windows or with 20-year-old practicals, embracing imperfection, and using the weather or time of day to create story-led moods.”

Working from a 130-page show bible, cinematographers Sereda; Bolter; Nadim Carlsen, DFF; and Christine A. Maier, AAC, BVK were free to interpret this palette in their own way, with the understanding that Mazin was interested in a loose, spontaneous style that took its cues from the game’s storytelling language but presented a look of its own. “In terms of colors, the world of the show is faded — the sun has washed everything out,” says Mazin. “And we tried to keep the camera grounded. When I was directing the pilot, I wanted to be in the moment, so we needed to keep the camera where a person taking part in the scene would be. That was my general philosophy.

The show’s cinematographers also found much inspiration in Mazin and Druckmann’s scripts. “There’s so much guidance in them, but they don’t tell you how to move the camera — they tell you what the characters are feeling,” says Sereda. “That gives you a sense of what to do.”

Sereda came to The Last of Us from character-driven Russian features like Beanpole and Mama, I’m Home. To give the camerawork a light, extemporaneous feel, she operated a handheld Arri Alexa Mini with Cooke S4/i prime lenses for much of her Last of Us work, in a configuration she calls “Backpack Mode.” As Sereda explains: “We took everything that is possible off the camera — batteries and antennas — and everything went in a backpack. Our 1st AC, Luke Towers, pulled focus remotely, as we kept the motors on the camera. The backpack was carried by dolly grip Paul Sheridan, so the operator only had the camera with a lens and a monitor in their hands, or on the shoulder. It was good for staying connected to the actors.”

When called for, series Steadicam and A-camera operator Neal Bryant employed a Cinema Devices ZeeGee rig, a three-axis “zero gravity” head that mounts to the arm of a Steadicam. “It mimics handheld,” says Bolter, “but it’s mounted to a Steadicam arm and allows for smoother and more controlled operating, particularly with long lenses. It also allowed us to set our desired handheld camera height, from the ankles to above the head.”

“Our infected are more of an obstacle to avoid. There’s tension-building and action to consider, but we were always careful to keep our focus on the characters and the story.”

— Eben Bolter, BSC

Cooke S4/i primes were chosen for the quality of their focus falloff. “You don’t feel the edge of the focus planes,” says Sereda. “With the Alexa, they produce an image you can believe in.” Her preferred focal length ranged from 25mm to 65mm, “which gave me the opportunity to get close to the actors without changing the shape of their face.”

Some of the show’s key set pieces were directly inspired by the game, including an early scene in which Joel; his teenage daughter, Sarah (Nico Parker); and his brother, Tommy (Gabriel Luna), realize that civilization is collapsing and try to flee Austin, Texas, in a pickup truck. Sereda operated her lightweight handheld rig next to Parker in the truck’s backseat as they rolled through a backlot of downtown Austin, whip-panning back and forth from over-the-shoulder to point-of-view angles of bloodthirsty creatures attacking screaming, panicked humans all in the same shot. The sequence ends abruptly when a commercial airliner crash-lands behind them in a massive fireball.

Compared to the game, the show downplays its confrontations with the monstrous human hosts of a mutated strain of parasitic Cordycep fungus. “Our infected are more of an obstacle to avoid,” says Bolter. “There’s tension-building and action to consider, but we were always careful to keep our focus on the characters and the story.”

Sad Beauty

Twenty years after the outbreak, humanity has lost almost everything, and nature has reclaimed much. Sereda had played the game years before her work on the show, and she remembers being moved by its sad beauty: “These stunning images of overgrown streets and houses, and the way people cling to life there.”

Production designer John Paino was tasked with redesigning these maze-like environments into real-life sets. Part of this design plan included a complete halt in technological development at the time of the collapse, leaving what’s left of society to make do with tungsten filament bulbs and sodium-vapor streetlights from 2003, running on a scarce supply of electricity.

The filmmakers likewise relied almost entirely on naturally motivated light sources. “For interiors, whether we were on location or on a stage, our lights were working through windows, and through openings in the walls and ceilings. There were almost never any lights on the set, which provided a lot of freedom for the camera,” Sereda says. A short Astera Helios Tube wrapped in cotton wool was often used to lift the shadows and lighten the eyes. At night, a soft toplight from Arri SkyPanels and LiteGear LiteMats was used to separate characters from the background. Other than the powerful period flashlights carried by the main characters, practicals were rarely used. Gaffer Paul Slatter and key grip Michael Taschereau worked on every episode of the show, which helped the cinematographers achieve a consistent look.

A Tender Aside

Bolter was brought on to shoot Episodes 3, 4 and 5. His first episode — the second to be shot and the third to air — is an almost entirely new storyline developed for the show, gleaned from a few vague clues in the game. “Long, Long Time” tells the tender love story of Bill (Nick Offerman), a lonely, paranoid survivalist, and Frank (Murray Bartlett), a lost soul who wanders into one of Bill’s homemade traps and bonds with his captor through a mutual appreciation of singer-songwriter Linda Ronstadt.

The episode takes place over the 20-year period between the outbreak and the present day, and was shot on a 20-day schedule in the late summer. The Midwestern-town exteriors were built on the edge of a Canadian forest, with interiors built on soundstages at Calgary Film Centre and Rocky Mountain Film Studios. “There was a huge commitment to making these spaces feel real and lived-in,” says Bolter, who employed many of the same techniques he used for the rest of his episodes on this quiet detour. “So much of this episode was about restraint. It felt disingenuous to change the lenses or the aspect ratio — or even introduce new colors.”

Bolter often embraced a lo-fi approach to sculpting light in this lo-fi world, using negative fill close to the actors, “and, if I needed something in the eyes, I would use the set — skipping light off of a table or the floor, or tweaking the position of a practical.”

A Cruel Winter

Sereda, Maier and Carlsen all shot portions of the series’ winter chapter. Directed by Bosnian filmmaker Jasmila Žbanić, Episode 6 offered Maier the chance to dabble in the American Western genre, taking her cues from such movies as Clint Eastwood’s 1992 feature Unforgiven (shot by Jack N. Green, ASC) and his Italian films with director Sergio Leone, as well as the natural beauty of the Canadian Rocky Mountains. Joel and Ellie track Tommy to Jackson, Wyo. — in reality, Canmore, Alberta — where a nearby hydroelectric dam provides the town with reliable electricity, good water pressure and a modicum of normalcy. Maier used longer focal lengths, up to 100mm, to film the newcomers from a distance, “like in the Old West movies where the stranger comes to town, and they’re the subject of everyone’s observation.”

The episode marks a turning point in the story, exploring a number of changes in Joel and Ellie’s relationship. Faced with separation, Ellie chooses Joel as her companion, and Joel accepts his paternal role for the first time. Maier stuck closely to the show’s established visual parameters, using mostly short focal lengths “to stay physically close to the characters and emphasize their inner emotional fights and anxieties, as well as their deep wishes for bonding. The threat in this episode doesn’t only come from the outside. It needed the warmth of this idyllic town, which echoes the normality of a past and a possible future.”

Maier notes that “compared to other episodes, this one is more quiet and contemplative. A lot was happening between the characters without anything being said. To find those moments, you have to feel for them in the stillness.” This “pure approach to emotional storytelling,” she says, served her and Žbanić well on their previous collaborations, including the 2020 feature Quo Vadis, Aida? — an award-winning film about the Bosnian War that all but shuns actual depictions of war.

Carlsen’s work with Iranian director Ali Abbasi caught Mazin’s attention after their feature Border debuted to acclaim in 2018. The two were hired as a pair for Episodes 8 and 9 of The Last of Us, which started production after the bulk of the season had been shot. First on his mind, says Carlsen, was “finding that balance between being new on the show and having new ideas about it.”

For his episodes, Carlsen relied on Bryant and series B-camera operator Carey Toner to handle the camera moves — a novel opportunity for the European cinematographer, who was accustomed to performing them himself. “I wanted to learn something from the experience,” he says, noting that “when I wasn’t operating the camera, I was able to see the set from the outside and feel what was working and what wasn’t, especially when it came to lighting.”

Carlsen’s approach to stage lighting added further layers of Light Grid Cloth, with some space between each, to the SkyPanel daylight sources. “I like it when it’s quite soft on the skin,” he says. “Episode 8 is set during the wintertime when it’s overcast and snowy, so I guess my approach lends itself to that kind of look.”

On their way to Salt Lake City, Joel is gravely wounded in an attack and left to Ellie’s care, until she’s captured by a group of ravenous cannibals led by the charismatic David (Scott Shepherd), and Joel must rally to save her.

Carlsen wanted to evoke a subjective feeling for the scenes involving Ellie when she’s beaten and captured, and Joel when he first regains consciousness, so he suggested the idea of doing point-of-view shots using fades and rolling focus racks — “both as blinks and lapses in consciousness, to convey a subjective rendition of what the character sees and perceives.” A-camera 1st AC Towers pulled focus with an Arri Wireless Compact Unit, and the fades were created by Carlsen with a CineFade VariND, giving him dynamic control over in-camera exposure without affecting the T-stop or shutter angle. “We wanted to bring that subjective, surreal vibe from the game into the show,” he says.

By the time Joel reaches Ellie, she’s already taken matters into her own hands, in the form of a meat cleaver. The scene, set in a burning steakhouse, during which she kills David in self-defense, is a noteworthy character moment and a memorable one for Carlsen. “It’s certainly heightened emotionally, but how we did it is what made an impression on me,” he notes.

He describes the setup, adapted directly from the game: “They’re on the floor and Ellie’s on top [gripping the cleaver], with the camera looking up at her from next to where David’s head is supposed to be. To create blood splatter coming back at her — and the camera lens — the special-effects department employed a lo-fi approach: simply having Bella repeatedly strike a large sponge soaked in fake blood positioned right below the matte box. Since this shot was Bella’s close-up, we didn’t need Scott to be placed underneath the camera, as he would’ve been out of frame anyway, but we raised her a bit from the floor with a pillow. We also added a clear filter to the matte box and wrapped the camera — and Neal Bryant — in plastic.”

Carlsen was thrilled by the unexpected results. “The more Bella struck the sponge, the more crazed she got — and more blood splattered on the lens, until all the light and color started to distort. It looked so right for the scene, and it feels organic because it came from the way we shot it.”

An Intricate “Dance”

The Last of Us co-creator Craig Mazin, who directed the pilot, has high praise for cinematographer Ksenia Sereda, RGC’s ability to execute what he calls “the dance” — the coordination of three cameras’ movement when capturing a scene.

“There’s a sequence in the first episode where Joel and Tess confront Ellie’s guardians, Marlene and Kim [Merle Dandridge and Natasha Mumba], in a long hallway, and Ellie’s between both sides,” he says. “These scenes are brutal to do: a lot of exposition, in a confined space, with multiple eyelines. We only had a day and a half to get everything, and I had this insane shot list, but there were so many moments where Ksenia was able to take four of my shots and turn them into one, because she understood how to block everybody so that we could get more at the same time. The more we get out of a scene like that, the more options we have in editorial.

“That’s an aspect of cinematography that I think is unsung. We think of cinematography mostly in terms of composition, light color and camera movement — not, ‘How much stuff can you give me to work with later?’ But every extra angle — every extra view of a boot, a shoelace, a hand, anything — is incredibly valuable. And Ksenia was a master of that. That scene could’ve been such a drudge to do, but it became one of my favorites because of her.”

— Iain Marcks

Naturalism for Explosive Action

By Eben Bolter, BSC

Episode 5 of The Last of Us features an action sequence set in outer Kansas that is easily the most complicated I’ve ever had to plan and shoot. Our characters are on the edge of town, walking and talking through a cul-de-sac at night to avoid being spotted, so I knew I’d have to do a large-scale moonlit walk-and-talk that felt naturalistic — not “lit” — and yet, present the characters, story and location to a TV audience clearly. This walk-and-talk would then develop into a stand-off against a sniper, a high-speed chase away from a speeding truck, and then a huge war scene with fire, explosions and 100 or so “infected” versus our heroes and the militia.

We built the cul-de-sac on a 2,500'x1,500' exterior piece of land near our CFC studios in Calgary, so I also knew I’d have to work with the effects department on a plan for set extension and have a plan to deal with the weather. Visual effects supervisor Alex Wang and I planned to do as much in-camera as possible, so instead of a bluescreen circling the set, we used a 40'-tall black screen and collaborated with the art department to introduce trees and foliage that would fall off into black beyond. Another key part of this process was our work with the locations department to turn off street lighting and any other polluting sources within a couple of blocks of our set.

For the moonlight, I needed large-scale, sourceless-feeling light that would work in multiple directions at the same time — based on our plan to shoot with four cameras at all times to get as much coverage of action as possible. My approach was to circle the set with 18 cranes, each supporting two Arri SkyPanel S360s with the most-focused 30-degree honeycomb filters to prevent any cross shadows from multiple sources. This gave us just enough of a beam width that in a walk-and-talk, just as one crane’s side light started to fade, the cast would be entering the next without cross shadows. Overhead, I wanted to have a moonlight “room tone” — a large and controllable soft source that would give me a little bit less contrast when I needed more ambient detail. Shooting night exteriors in Calgary, where winds can become an issue, balloons and textiles weren’t an option. So, gaffer Paul Slatter and I came up with a large-scale solution: Four construction cranes each held a grid of 96 6' bi-color LED tube lights in a grid formation of 40'x20', totaling 400 individual lights. We ran these anywhere from 2% to 20% output, depending on need — but they averaged out mostly at around 5%.

This grid effect would allow wind to pass through, while the quantity of lights would give an ambient and soft-enough room tone, in place of a textile. I wanted the moonlight to have a just colder-than-neutral, silvery look, without slipping too far into “movie moonlight.” Knowing that I would have real fire sources after the explosion, we rated the cameras at 3,200K and targeted our moonlight sources to 4,000K with a very small amount of added green. Once the fire started, I would select certain S360s and overhead tubes to simulate fire, and we used some off-camera Dinos, too — on the ground with a half CTO frame to bring it closer to the color of fire — when we needed a bit more throw and hard shadows with fire effects.

(as told to Iain Marcks)

You'll find a gallery of additional images from the production here.

1.78:1

Cameras | Arri Alexa Mini

Lenses | Cooke S4/I