Set Lighting Innovations Mark the Photography of The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T

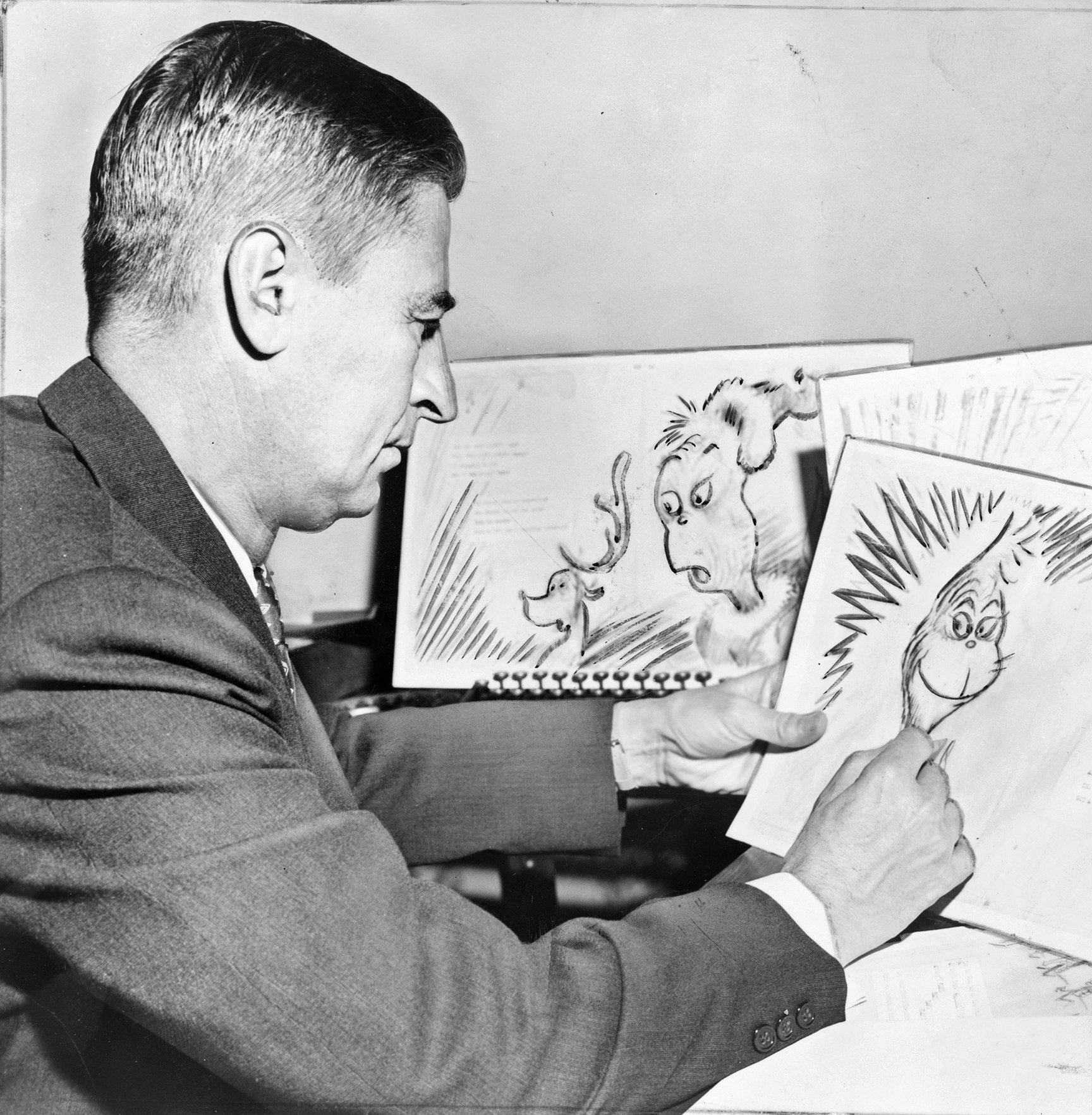

Frank Planer, ASC used reflected, ultraviolet and fluorescent light in revolutionary ways in photographing Stanley Kramer’s fantasy film.

This article was originally published in AC Jan. 1953. Some images are additional or alternate.

A fantastically creative masterpiece of wild imagination has opened the eyes of all Hollywood — eyes which over a long period have become accustomed to spectacle in virtually every shape, shade and form.

The picture in question is the Kramer Company’s musical extravaganza in Technicolor, The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T, conceived as an entirely new and vital approach to entertainment via movies.

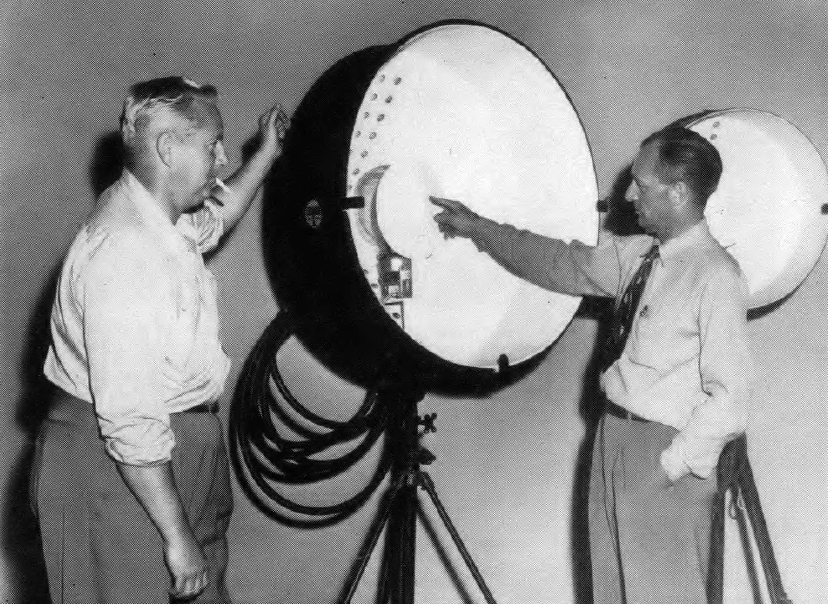

Director of photography Frank Planer, ASC added a new touch to the filming of 5000 Fingers when he devised anew means of changing lighting and color before the very eyes of the moviegoer by interspersing use of ultraviolet and fluorescent light. Another innovation was the use of the new cone lights, developed by Columbia Studios’ electrical department and described in American Cinematographer June, 1952. Cone lights are said to produce the broadest and most distant “shadowless” light ever attempted in motion picture production. Planer found them made to order for lighting the sets of this production.

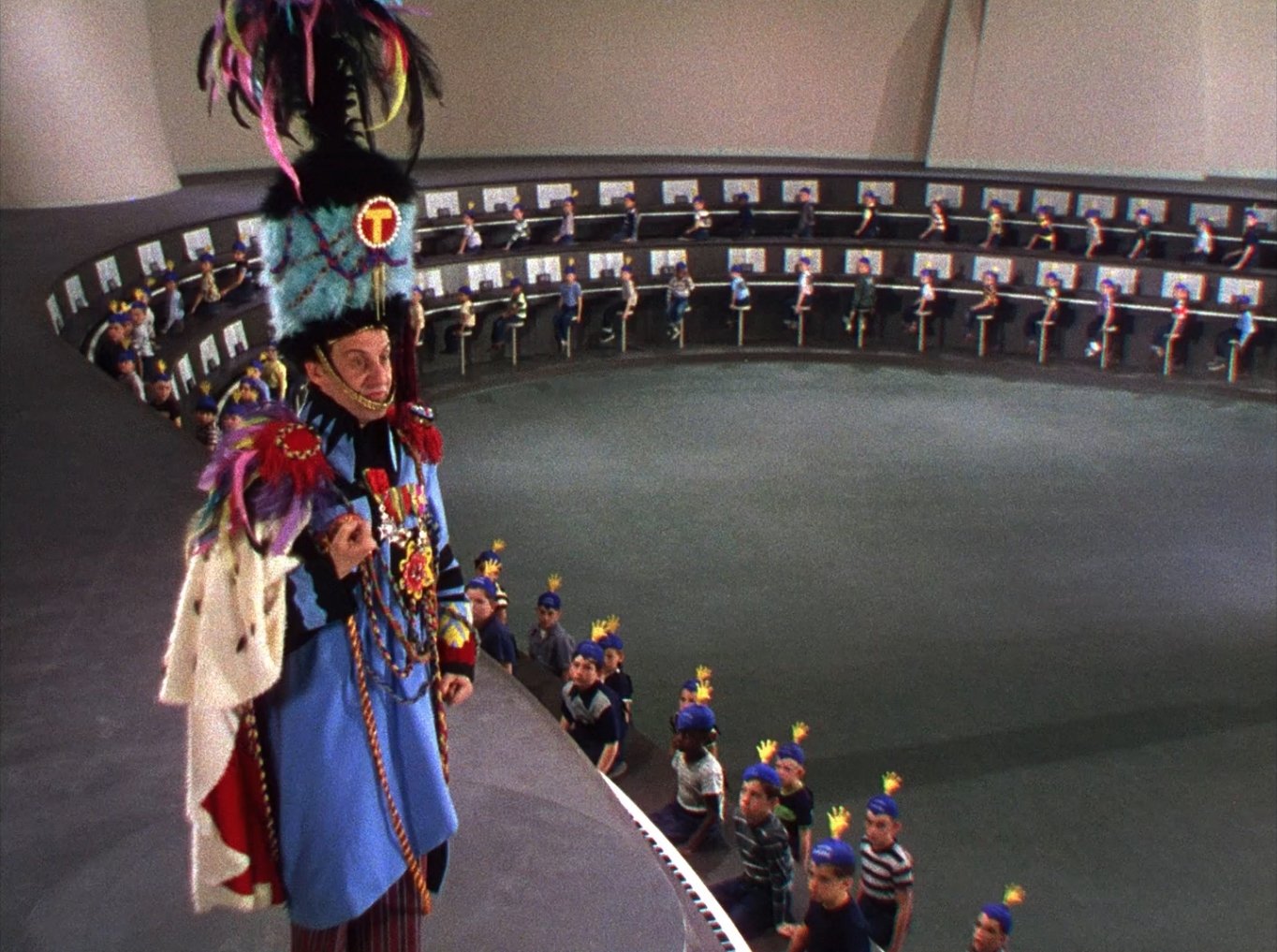

The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T comes to the screen as a vision, the dream world of a nine-year-old boy. It is painted his way, not Rembrandt’s way. The sets are crookedly fantastic as a small boy would draw them. The entire picture is wildly imaginative, as only a small boy can imagine. And contributing most effectively to the overall pictorial effect is Frank Planer’s unique lighting for the Technicolor photography.

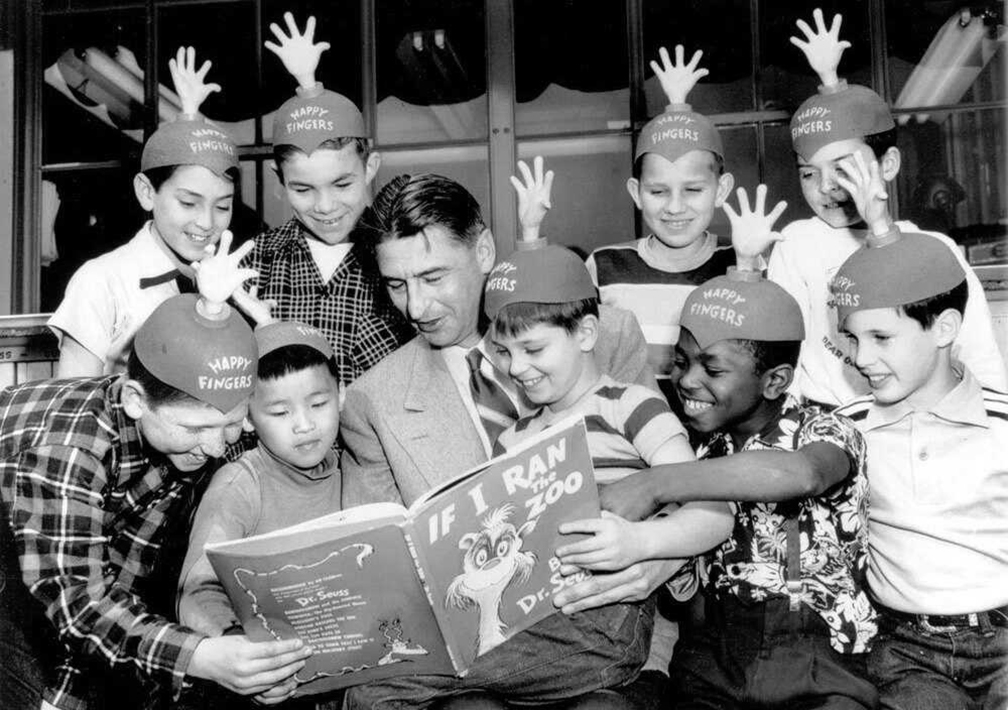

Briefly the story concerns a typical American boy whose mother has her heart set on him becoming a piano virtuoso. His teacher is Dr. Terwilliker (Dr. T.) who shares the mother’s view that the lad will learn to play the piano, "even if I have to keep him at that keyboard forever!" One day when the lad would rather be outdoors playing baseball than practicing his piano lessons, he falls to daydreaming. Dr. Terwilliker becomes an ominous ogre with 500 little boys trapped in his vast piano courtyard. here the boys are destined to sit at the giant keyboard practicing 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, 5,000 fingers practicing the scales in unison.

The lad seeks to escape from Dr. T, and what he encounters in weird and fantastic dream situations makes for one of the most entertaining pictures of the year and made for Frank Planer perhaps the most challenging assignment in color photography of his entire career.

“In short, what we sought photographically was the effect of a typical Walt Disney cartoon, done in live action.”

— Frank Planer, ASC

To begin with, Planer faced something radically new in sets from the standpoint of lighting. According to him, 5000 Fingers utilizes more sets than any picture in his recollection; at one time sets for the production occupied every sound stage on the Columbia lot.

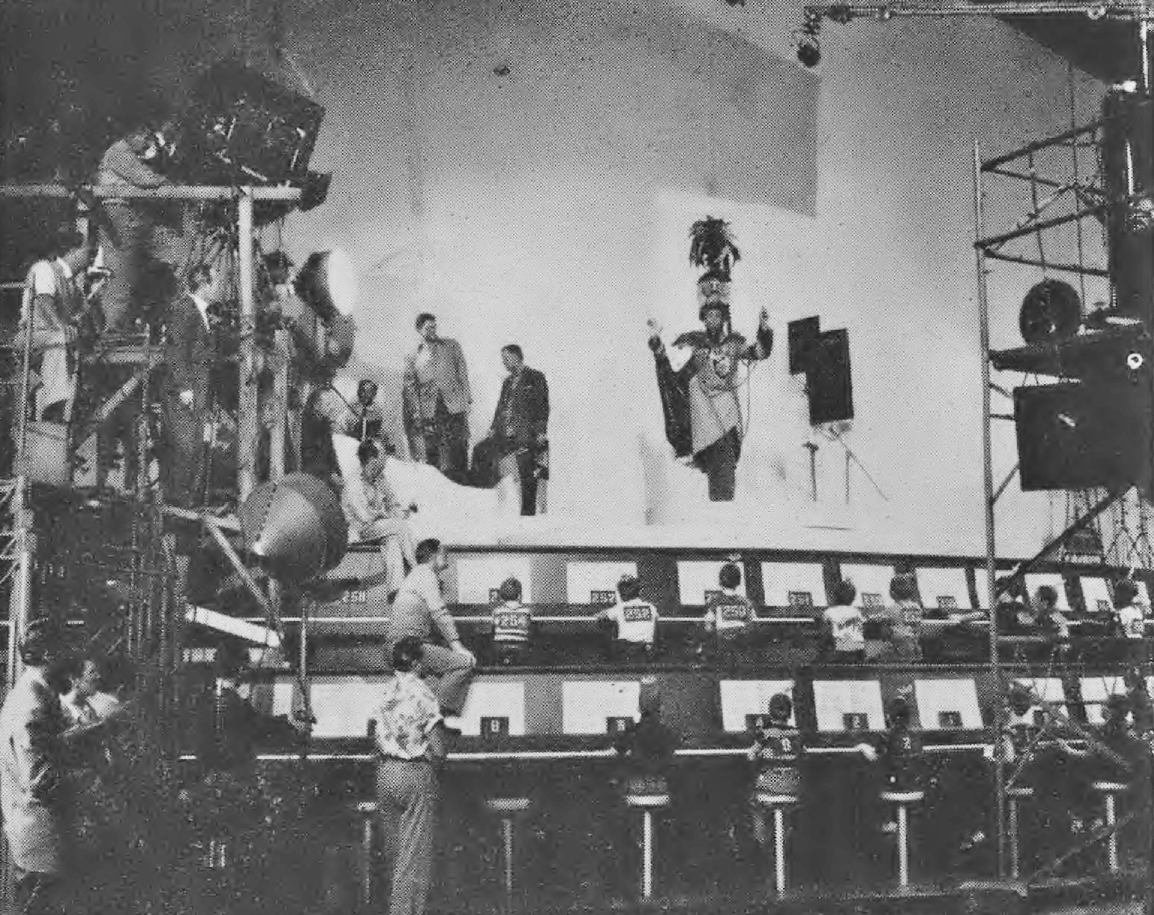

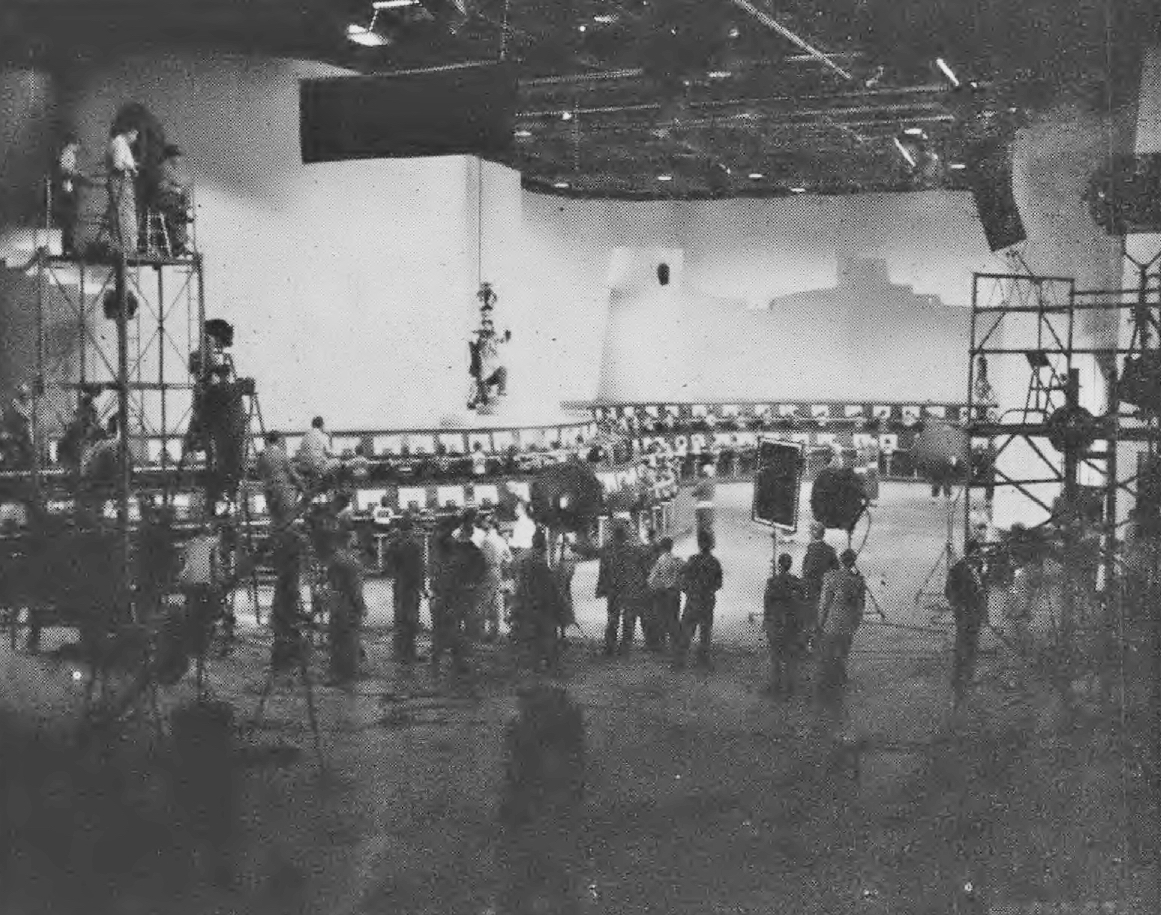

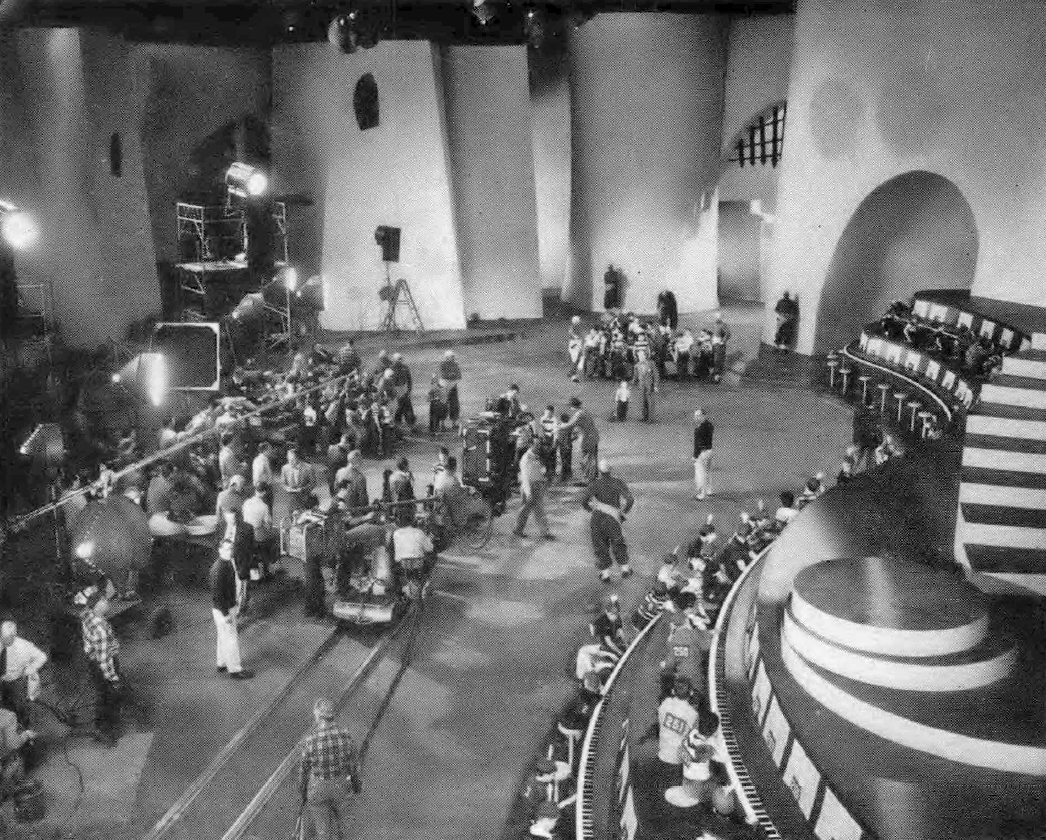

Largest set in the film and one of the biggest ever to grace a motion picture screen was the giant piano courtyard of Terwillikerland, which occupied all of stages 8 and 9 at Columbia Studios. Its biggest feature, of course, was the longest piano keyboard ever built.

Stretching the length of the immense courtyard which featured weird staircases, entrances to bottomless dungeons and topless staircases, the piano completely dominates the scene. The courtyard set, one of the costliest ever built on the Columbia lot, was constructed mostly of battens covered with white muslin, 3,500 square yards of it, instead of the conventional wallboard. The reason, of course, economy. But this placed a tremendous burden on director of photography Planer, for unlike with sets of solid construction, he faced innumerable problems in lighting. The muslin, being translucent, precluded placing lights in rear of the sets, unless certain areas were carefully goboed or backed up with wallboard flats, black backing material or both. In lighting the narrow staircases, special cutouts were mounted before the lamps in order to funnel the beam of light so it wouldn’t strike the muslin covering of the sets and thus reveal the flimsy construction.

The lighting equipment Planer used is one of the interesting highlights of the production. The cone lights, which Columbia lighting engineers had just introduced for test purposes, were used in large scale for the first time in 5000 Fingers. Planer had observed them during the tests, decided they were the ideal light source for illuminating the tremendous areas of the larger sets. The cone lights give a reflected illumination of soft, "shadowless" quality, are capable of lighting larger areas than most other type set lighting units, and greatly reduce rigging and maintenance costs. In all Planer used 24 cone lights and 6 arcs (Brutes) for set lighting.

Hydraulic parallels were widely used, both for camera and key lights. These proved most ideal whenever camera position was changed; the lamp parallels were simply rolled to another position and the platform lowered or elevated according to the key light height desired. In many cases, the hydraulic parallel proved a better mount for the camera than a crane because of the greater height range. This was especially true when filming on the huge piano courtyard set which required shooting from great heights.

The most challenging problem, of course, was how to get detail and modeling into the all-white muslin covered sets. Although the contour of walls, staircases and other details were readily apparent to the eye, no detail had been emphasized through painting of the sets. This was left to Planer, whose challenge was to so light each set that details were brought out with contrasting shadows, and by delicately shading the light on set walls and background to give the desired separation. The scenes on this set were perhaps the only ones filmed in full scale lighting and embracing the complete range of color.

When the company moved to the dungeon and the Mound Country sets, both photography and lighting assumed a completely new pattern. Here the boy’s experiences in attempting to escape his dilemma were staged. Pointing up the mood were the dark, low-key sets, the eerie mood lighting contrasting with metallic coloring of the mouldy characters in the dungeon, and the nightmarish aspect of the Mound Country and the weird butterfly men who pursued him.

Here color was deliberately underplayed; indeed for the most part there was little or no color in the sets. Only the boy appeared in full color against the negative backgrounds, a photographic innovation which becomes a pictorial delight on the screen.

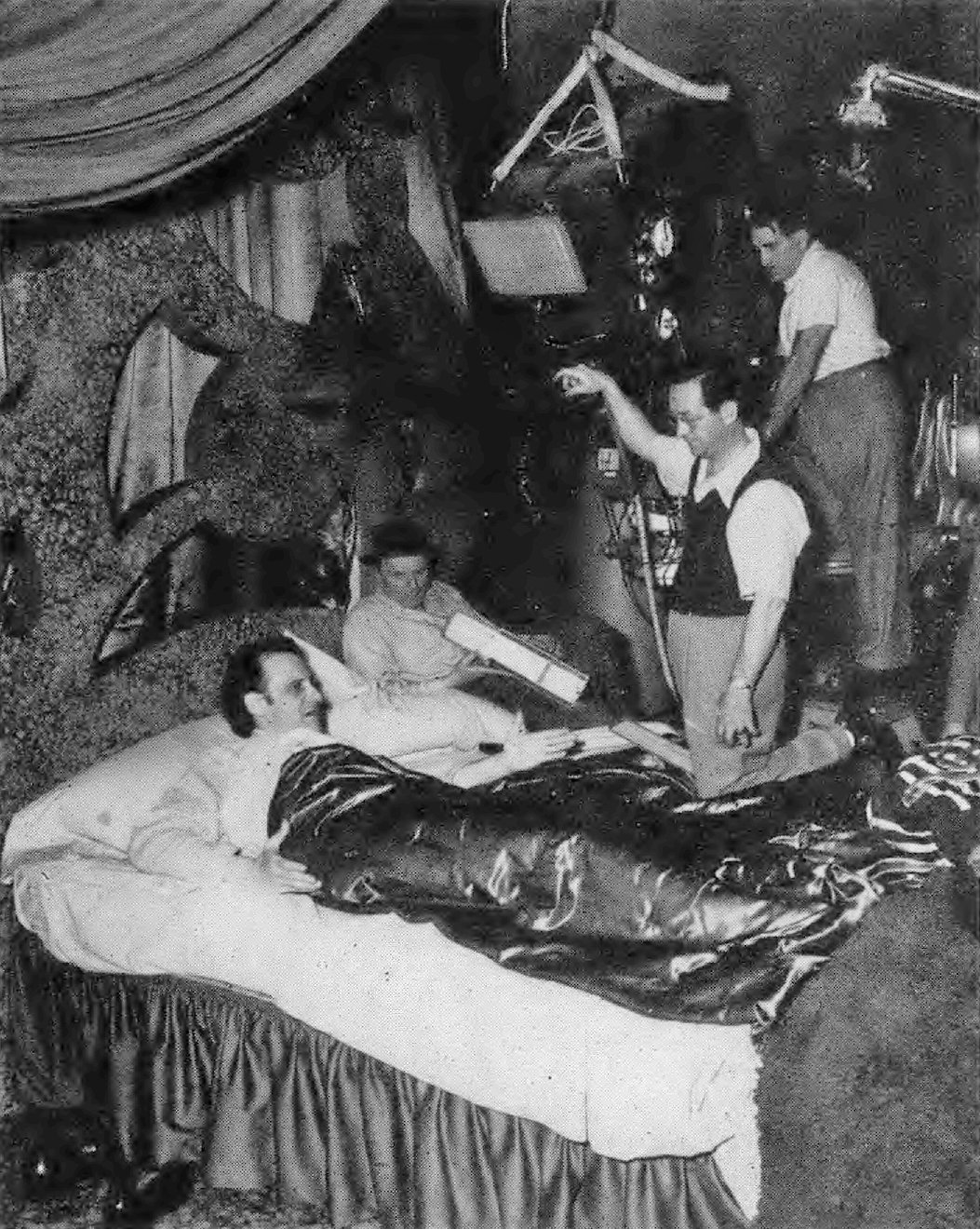

The pictorial effectiveness of the dungeon scenes, wherein a score of demented, mouldy-looking musicians play fantastic instruments, is enhanced by striking use of colored light and green, luminous makeup. When first he shot this scene, Planer employed conventional set lighting with disappointing results. He changed the lighting pattern completely, lowering the key and adding color to the light. Here also he employed ultraviolet and fluorescent light with great effectiveness.

Another interesting innovation was that employed by Planer when shooting closeups of the characters of the Mound Country. To enhance the illusion of moonlight, a narrow beam of colored light was directed on the eyes of the men, a different color for each one.

An unsuccessful attempt was made to photograph the familiar stage technique of reversing the coloring of subjects by painting them with luminous paint and then switching from regular incandescent to ultraviolet light. Only in the closeups did the transition register completely; it wouldn’t record at all on the film in medium and long shots. The reason, Planer learned, is that it was impossible to build up any appreciable illumination volume with ultraviolet light.

For all closeups, other than those mentioned immediately above, Frank Planer used his familiar Houdini eyelight, a narrow, hand-held incandescent unit which he employs to cast the small pin-point of sparkling light that gives life to the eyes of players in closeups. This. Planer handles himself, crouching just below the lens hood of the camera and directing the light on eyes of the player as necessary.

Planer is loud in his praise of the new Columbia cone lights. The quality of illumination they give is the most ideal for color photography, he says, adding that conventional harsh lighting invariably takes away some of the quality of color.

"The use of cone lights," said Planer, "made it easier to light those sets which called for the addition of matte shots at the top. The piano courtyard set especially, while it extended clear to the ceiling of the sound stage, was heightened further pictorially in the finished result through effective matte shot photography. this called for a special quality of lighting on the overall set, and this the cone lights provided most successfully."

In analyzing the photography of 5000 Fingers, Planer said the aim from the very beginning was to picture the scenes and players from the viewpoint of a child, employing fantasy through lighting and camera treatment. "In short, what we sought photographically was the effect of a typical Walt Disney cartoon, done in live action."

Access the every issue of AC and every story from more than the last 100 years with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.