Malcolm X: One Man’s Legacy, to the Letter

Spike Lee and Ernest Dickerson, ASC craft an epic vision retaining the humanity of a figure who has been turned into a political icon.

Whether exploring an African-American woman's sexuality (She's Gotta Have It) or negotiating the intricacies of interracial romance in urban America (Jungle Fever), Spike Lee has always taken the controversial issue and made it a personal statement. Whether successful or not, those statements, or "joints," as Lee calls them, are always deeply grounded in the immediacy of the moviegoing experience. That sense of immediacy is guaranteed by Lee's collaborator and cinematographer, Ernest Dickerson, ASC.

Lee and Dickerson have collaborated again on a "joint" intended to recreate the life of a man who, according to Lee, "rose up from the dregs of society, spent time in jail, reeducated himself and, through spiritual enlightenment, rose to the top." That man was Malcolm X, and the movie attempts to recreate the landscape of the political and the personal upon which his life and death were played out. The photographic approach of the film is reflected in the publicity poster for Malcolm X: a grey capital letter X against a jet black-background creates an image that is stark, bold, simple — and very powerful.

“Spike and I have been noted for very expressive camera moves, and on this film we went for a more stripped-down classical style. There aren't a lot of Louma crane shots or wild moves," Dickerson says.

Lee and Dickerson used David Lean's Lawrence of Arabia as a primer for the epic sweep and classical style of Malcolm X, going so far as to seek a 70mm release. Budget restraints prevented filming in 65mm, however, so Dickerson worked with the 1:85 aspect ratio to approximate the scope and compositional freedom of 70mm.

A film of epic scale was always foremost in the filmmaking duo's visual plan. As Dickerson says, 'Warner Brothers wanted a two-hour movie, but we always intended to shoot a three-hour movie."

Given the vibrancy and magnetism of Malcolm X, and the turbulent period that forged him, it's hard not to see the film as an epic. But the film qualified on practical terms as well. The production re-created four decades of American history and was filmed on three continents. Three hundred people, working over six months, lent their skills and services to the creation of the various buildings, sets, costumes, and facades needed for the picture.

Dickerson and production designer Wynn Thomas began the massive work of defining the look of this sprawling project by breaking the narrative down into three parts designed around the manipulation of separate color schemes. According to Thomas, the film's palette moves "from rich warm shades to monochromatic cool shades to earth tones — browns, greens and natural tones - that reflect controlled realism." The changes in color track the growth of Malcolm X from his ignoble days as a street hustler to his eventual stature as one of the most profound catalysts of the civil rights movement.

Maintaining the integrity of this design plan on such huge film required a detailed guide. ''The script is my guide," Dickerson is quick to point out. "I jot down the path I'm going to take in the script margins. After I've worked out the progressions, I put them in. I jot down diagrams and feelings I have for photographing certain characters and sequences."

The screenplay is Spike Lee's rewrite of the James Baldwin script that was to have been produced in the 1970s, when ''blaxploitation" films helped keep Hollywood afloat before the Lucas/Spielberg connection redefined the industry.

Perhaps because Dickerson has also directed (he helmed the 1991 coming-of-age story Juice), he understands the importance not only of lighting and composition, but also of actors working a scene through to a dramatic payoff. He describes one such scene, a small but key moment in the film between Malcolm and his wife, Betty.

"Betty was trying to convince Malcolm that there were people out there who wanted to betray him, [but] Malcolm had put blinders on, trying to ignore that fact," Dickerson relates. "The scene starts out as a conversation and winds up as an argument. It moves from the living room to the kitchen to the dining room, ending up, finally, in the bedroom. For the most part, it was done in one take.

"It was good for the actors," he adds, ''because it let them build up energy and then let it out. The scene was also exciting for Phil Oetiker, my operator, and Gary McCloud, my focus puller. The camera was moving and handheld, so that we got a visualization of the tension in the scene. There are other scenes that Spike and I thought would work in the same way if we just let them play out in one take."

Dickerson's respect for the actors' needs allowed him to develop a special working rapport with the actors, especially the film's star, Denzel Washington. "An actor like Denzel Washington helps me as a cameraman because, while I'm photographing him, I believe him. He [also] has a face that just takes light nicely."

Lighting the many-hued faces of the predominantly African-American cast was an interesting challenge to Dickerson. 'I rely on reflective readings," he says. "I'll use an incident reading just to get me in the ballpark, but for fine-tuning the lighting I'll always use a reflective reading with a spot meter. I also work with the makeup person, making sure that the darker-skinned people aren't 'dulled down' too much. I do this to make sure there is some reflectivity in their skin."

Dickerson also uses composition to remain photographically true to the full range of skin tones and colors in African-American actors. 'With darker-skinned actors, you may stage the scene so that the actor is closer to the key light and getting a little bit more light. For instance, for a scene with a light-skinned person and a darker-skinned person talking by a window, I'll stage the scene so that the darker-skinned person is closer to the window."

The cinematographer also sought to exploit the full range of his stocks (5245 for exteriors, 5297 for daylight interiors, and 5296 for night exteriors) to capture the color gradations and tones of the actors. "I really like the 45 quite a bit," he says. "I tried to use that as much as possible for exteriors."

Dickerson is a strong believer in "trying to get it in the photography," adding that ''I like to see in dailies, as much as possible, what the final film is going to look like. I tend to do very little fooling around with the film in the answer print stage. I like to see it happening; I want to see if my effects are working: Anything that has to do with color I do in the principal photography. I try to give the lab as little as possible to do." Dickerson provides the lab with a neutral grey scale every day to show what his neutral light is. To establish his grey scale, he always keeps one light set at a color temperature of 3200 degrees Kelvin.

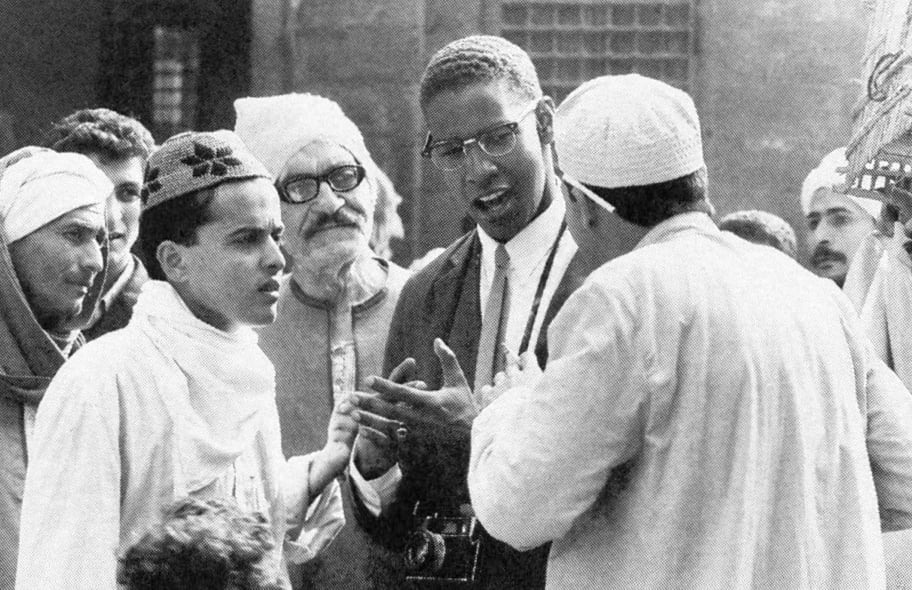

This control of light and color proved difficult when the production moved to Egypt. Many of the resources the production had become accustomed to weren't readily available. "Egypt was complex because they didn't have a wide range of equipment," Dickerson says. 'We were told that they had 12Ks and other equipment, but they didn't. In the States, we were spoiled - we actually used the new 18K lights. I had two in my principal package and they were quite beautiful. In Egypt, we didn't have much. I had reflectors (shiny boards) and HMI Par lights; the brightest light I had there was a 4K."

Budget limitations prevented the production from transporting any lighting units from the U.S., but allowed Dickerson to use more of Egypt's natural light. ''I just manipulated the available light," he recalls. "The light was very warm and hazy. There were a lot of clouds, so we had a very soft, scattered light. Sometimes the sun would try to come through and the light would have a little directionality to it.

'The dust in the air created a sandy color, and the pollution, which was very heavy, also helped scatter the light along with the humidity in the air," he adds. "I also used a light Harrison & Harrison control." diffusion because I wanted a soft glow on highlights. I used polarizing filters as well. It's [a technique] I picked up from my still photography days. The filters are standard equipment for me; they give me more color

Control, especially creative control, was an important issue on this film. The production was plagued by all kinds of financial pressures that threatened not only Lee's directorial authority, but the completion of the film itself. These pressures ultimately led Lee and his producers to seek additional financing from African-American celebrities like Bill Cosby and Oprah Winfrey. Despite the fiscal wrangling, the original vision of the film was preserved.

Finance was not the only force with which the filmmakers had to contend; at one point, religious beliefs compelled Dickerson to craft the film's look by proxy. Malcolm's sacred trip (or "hajj") to Mecca was a major turning point in Malcolm's life and in the dramatic thrust of the film, but shooting in Mecca required a Muslim crew. "David Golea, a Muslim, was the director of photography for the Mecca shoot," Dickerson says. The Mecca material, mostly wide coverage of the environment of the city, was second unit. "The material was shot before we started principal photography on Malcolm," Dickerson continues, "so my photographic plan had to be laid out well in advance."

Six months after the second unit material in Mecca was shot, Dickerson and his crew went to Cairo, Egypt. Three months were spent negotiating and planning for 10 days of filming in that city. The Cairo material doubled for the Muslim cities of Jetta and Mecca, as well as for the early ’60s version of Cairo itself.

Though Egypt has been modernized, Dickerson was able to find areas that doubled for the city in the film's period. That problem was not so easy to solve when it came to shooting the New York and Boston sections of Malcolm's life. Locations had to reflect Boston in the Forties and New York from the ’40s through the ’60s, and production designer Thomas notes that "this was an enormous job, bigger than it may appear on the screen."

Thomas reveals that the Boston material was the most difficult to re-create. "We needed to show a large intersection, and since the camera angle gave visual access to streets on all sides, we actually had to recreate a significant section of the city, complete with railroad tracks, houses, stores and everything else you'd be able to see."

While the logistics of creating these environments were taxing, coordinating and setting up the shots for these sets, which were peopled with huge numbers of extras, proved to be a challenge for Dickerson and his crew. For a scene in which approximately 5,000 extras celebrate a Joe Louis boxing victory, Dickerson recalls, "We started tight on Malcolm experiencing what was going on, then went up and up and up and up to get a wider and wider view of our recreation of Harlem's 125th Street.

"I put a Louma crane on top of a Titan crane for the shot. The Titan crane went up and then the Louma crane went up even further. The shot was huge, with the crowd in period costumes and the period cars and buses." Lighting these crowd scenes required a number of 12Ks and Maxi Brutes.

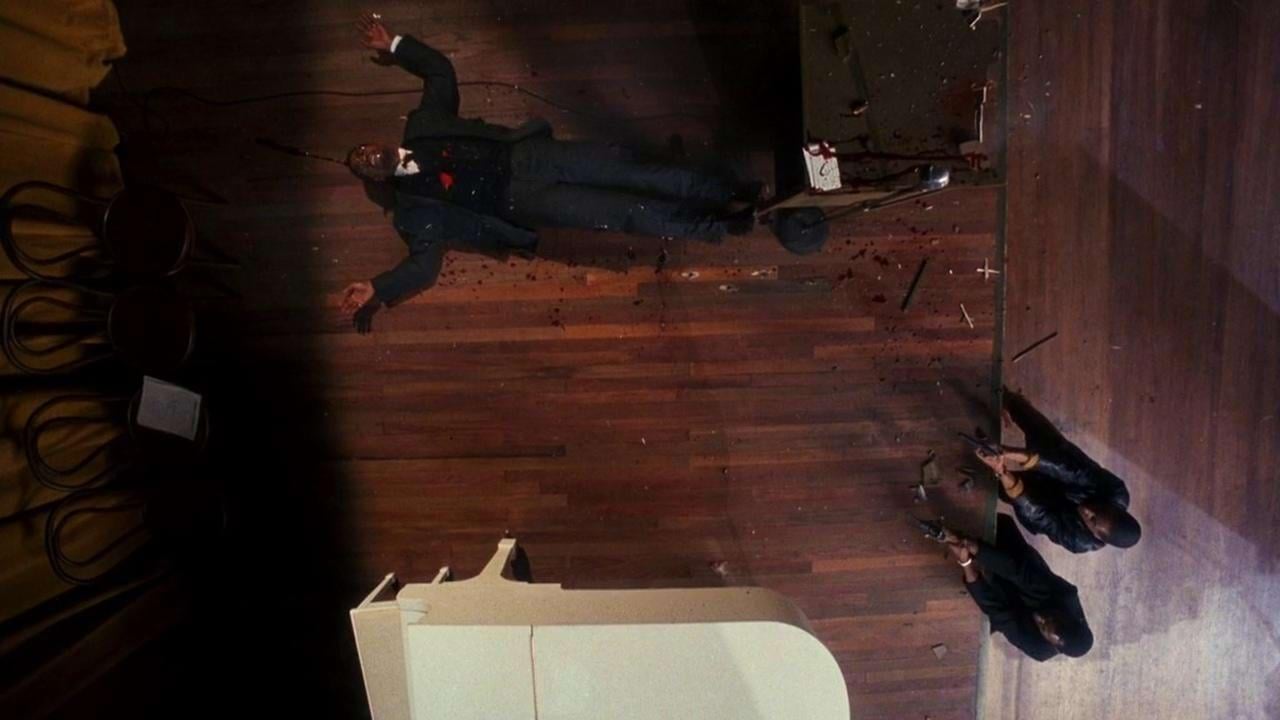

Lest anyone think that Malcolm X is all period costumes and sets and huge lighting setups, Dickerson points out that the film's true focus is the man and the effect he had on the people around him. Dickerson notes that filming the grisly assassination of Malcolm X "had a profound effect on everybody, especially the guys playing the assassins. This sequence was saved for the end of the production. After we did the first take, the guys playing the assassins excused themselves from the set, and, I understand, went into the men's room and started crying like babies."

Dickerson recalls that "Denzel did something interesting in a take of the assassination scene. The shot has the camera moving into a close-up of Malcolm just as he realizes what is going on. Malcolm gives the assassins a little smile and then, boom, he's gone. It was [as if he was thinking] 'Finally, it's here."'

Scenes just prior to the assassination were also imbued with a number of subtle touches. "For a sequence in which Malcolm is driving in a car on the day before the assassination, we had an extra dressed in black in the car behind him. Even though the focus is on Malcolm, you see this dark figure out of focus behind him, almost like the angel of death riding next to him and watching him. I think this dark figure registers almost subconsciously."

Dickerson points out that the color schemes mentioned earlier are also intended to work at a subconscious level, especially in the film's first third. "Wynn Thomas and I decided that this was going to be the most colorful part of the film. We wanted to make it very romantic. We wanted very warm colors, as if Malcolm were in the womb waiting to be reborn.

"Once Malcolm was arrested and spent time in prison, I wanted to go from that warmth to the shock of the coldness of prison," he adds. "The color scheme for prison was pretty much greys, blacks, and bluish-greys. The lighting scheme was fairly cool and I eliminated all diffusion. We went for a very hard and very cool, stark vision."

The sequence where Malcolm sees the vision of Elijah Muhammad in prison is bathed in a golden light. Once Malcolm is out of prison, Dickerson enacts another subtle change in the color scheme to reveal Malcolm's rise in the Nation of Islam. "I went to a more normal color scheme, with no diffusion," Dickerson says. "It's a very clean, no-nonsense look. That's how I saw the Nation of Islam, as very straightforward and no-nonsense." This section of the film in particular reflects the "controlled realism" that production designer Thomas and Dickerson were trying to achieve. Diffusion was used very selectively-Harrison & Harrison filters and nets in brown and black tones.

Lee says that he and his team hoped to use the visual progression of the film to show that Malcolm was "five or six different people. I believe that his search for truth made him change over and over again, and it would be an injustice to his life to take any shortcuts in our film." Dickerson and his production crew followed suit, successfully avoiding the obvious in creating an epic vision that also reinforces the humanity of a figure who has been turned into a political icon. Like the letter he chose to symbolize his political and personal struggle, Malcolm X signified the unknown factor in a people's move toward an evolving humanism.

Lee was honored with the Society's Board of Governors Award at the 38th Annual ASC Awards on March 3, 2024.

Click here for more archival stories from American Cinematographer.