Space Oddity: The Man Who Fell to Earth

Tommy Maddox-Upshaw, ASC details his visual approach to this forward-thinking sci-fi series that explores today’s realities.

Photos by Aimee Spinks and Rico Torres

Continuing an established story offers unique creative opportunities, but for Tommy Maddox-Upshaw, ASC, shooting the socially aware science-fiction sequel series The Man Who Fell to Earth also presented a steep learning curve in terms of the genre and the necessary production complexity. Fortunately, as he notes, “I was an athlete as a kid, and you always want to take on the challenge.”

The Showtime series picks up 45 years after Thomas Jerome Newton (played by David Bowie in the 1976 feature film of the same name) arrived on our world seeking to save his own. Because Newton failed in his mission, a second alien from the planet Anthea — Faraday (Chiwetel Ejiofor) — has come to acquire the precious resource necessary to revive their dying planet: water. The 10-part series begins with the extraterrestrial turned tech mogul speaking before an enthusiastic audience in a type of TED talk. Polished and articulate, and made wealthy from patents based on Anthea technology, he has come far since crash landing near Los Alamos, N.M., barely able to speak. The series traces his evolution, aided by discredited nuclear physicist Justin Falls (Naomie Harris), as others — including the CIA and the nefarious Flood family, which now controls Newton’s legacy — become increasingly interested in learning who Faraday really is. Meanwhile, the aged Newton (played by Bill Nighy), is advising Faraday, his mentee.

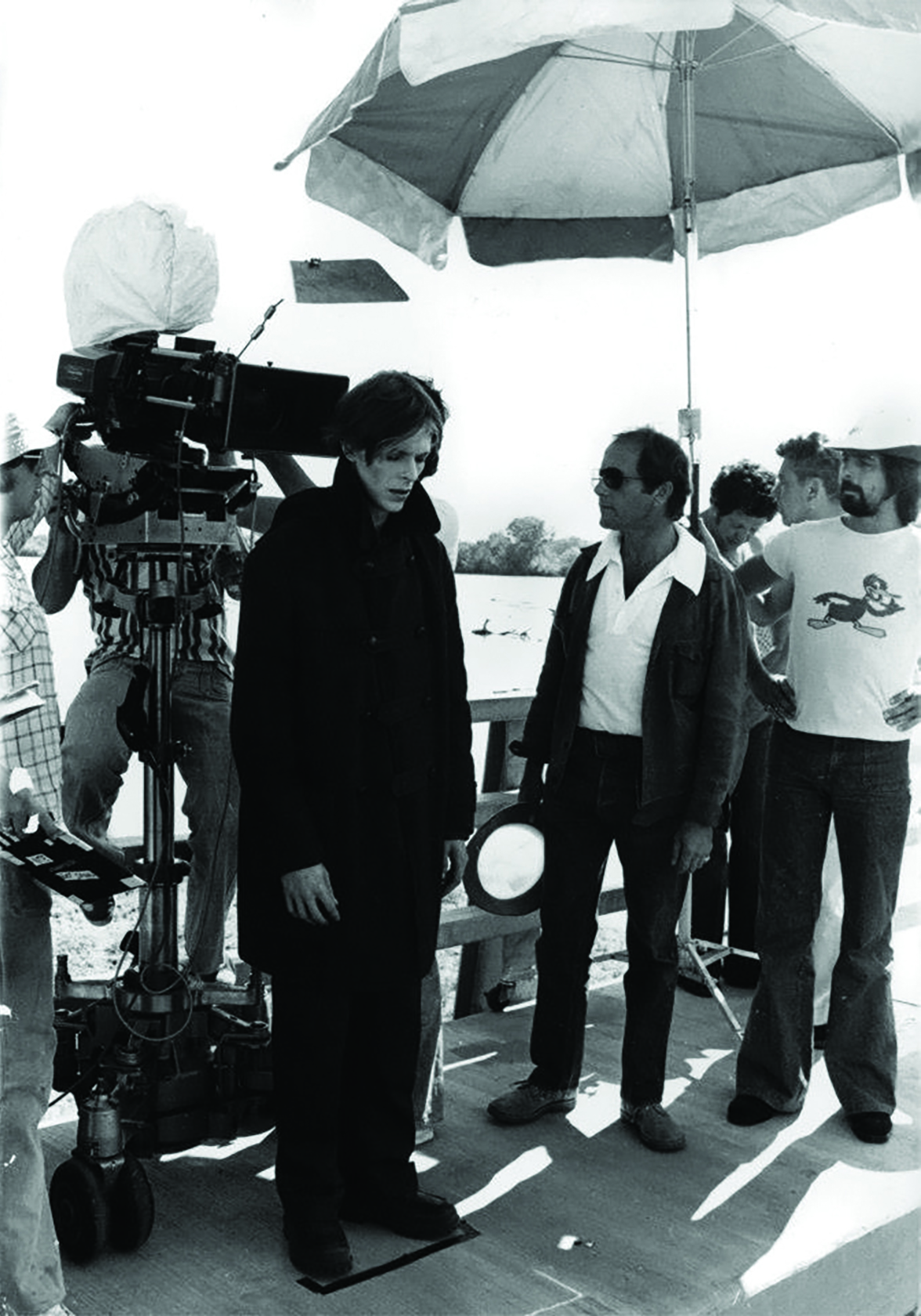

Maddox-Upshaw, director of photography on the first four episodes of Man Who Fell and half of the show’s finale, was admittedly nervous about walking in the footsteps of the iconic 1976 film, directed by Nicolas Roeg and shot by Anthony B. Richmond, ASC, BSC. “I knew the cult following the film has, the love for Bowie and the character he created with such subtly, and the weirdness of the cinema and the stuff it talked about,” he explains. “I also know Tony Richmond. He and I are friends. And I love Bowie and everything that he stood for in terms of pop culture, being an artist, and his very vocal views on race in America. He was ahead of his time and so unapologetic about it.”

The cinematographer has also long been a sci-fi fan, yet never before worked in the genre: “I’ve been a sucker for sci-fi ever since seeing [the 1985 space adventure] Explorers. Now to be able to lens it is fricking awesome.”

Neither the 1963 novel by Walter Tevis nor the 1976 film had much bearing on the new series’ look. “We’re now at a different chapter of where Newton is, and the home planet, too,” Maddox-Upshaw explains. “We had to world-build and show that time has passed. That required us to differentiate ourselves from that work for the most part.”

Written by executive producer and director Alex Kurtzman and executive producer Jenny Lumet, the show’s themes are different as well, and more relevant to today’s conversations. “There’s just so much in it: gender, race, equality, immigration,” Maddox-Upshaw says. Speaking of Faraday and professionally disgraced scientist Falls, who are both played by Black actors, he asks, “Why him? Why her? What does it say about the racial implications of Justin being this smart Black woman who hasn’t fully had an opportunity [to become an accomplished scientist like her father]? What does it say about her dad being an immigrant? Faraday’s an immigrant, too. What does that mean? What’s the social commentary?”

This was the cinematographer’s first time working with Kurtzman, best known for his many recent voyages in the Star Trek universe, both in television and the feature realm. “Being a Black cinematographer in this Hollywood space, I felt for years I always had to prove myself to the room,” Maddox-Upshaw says. “From Day 1, Alex Kurtzman never made me feel like I had to prove myself to him or to anybody we were working with. It was always an open collaboration, which is freeing and different.”

The cinematographer notes that he worked alongside many people of color on the crew, including his A-camera operator Andrei Austin, A-camera focus puller René Adefarasin, 2nd-unit director of photography Yinka Edward, and camera trainee Bradley Panda — as well as women, including B-camera 1st AC Joanne Smith and B-camera 2nd AC Melanie Jansen, among others. “Not to say that [A-camera] 2nd AC Jonathan Tubb, DIT Daniel Alexander and loader Étienne Suffert didn’t add to the mix of our inclusive band of misfits in the camera department,” he says. “It was quite inclusive, between the people of color, white men and women [in all departments]. Within our crew and day players who came on from different departments, people were surprised that a show this size had so many diverse crew members. It was part of the ether of this production. That’s something I try to do here in the States quite often in my hiring practices, and I wanted to do that on this international production as well.”

The cinematographer was exposed to visual-effects techniques while operating on Iron Man 2 for Matthew Libatique, ASC — but never on this scale, noting, “I think this show has 300 to 400 [shots requiring effects work] per episode.” He credits two VFX experts with showing him the ropes: Simon Carr, VFX supervisor in the U.K., and Jason Michael Zimmerman, coproducer/VFX supervisor in the U.S., who often works with Kurtzman. His takeaways? “Always make sure there’s talk of an approach before you get there. Then double down once you’re there and don’t make any assumptions about what the VFX are going to be.”

However, the show’s special look owes just as much to stylized techniques achieved in-camera. That’s especially true of shots that convey Faraday’s state of mind. These kick in just after he’s arrived on Earth and is overwhelmed by the sights and sounds of human beings — and water, the precious resource he’s after. Soon after Faraday lands, he’s seen naked, staggering to a gas station where he spots a water hose. There’s a quick-cut barrage of extreme close-ups of the hose gushing water, his mouth drinking, and other details.

These shots were accomplished with a Venus Optics Laowa 24mm probe lens, the first of many such uses for its wide angle of view. With its 16" barrel, the Laowa has a minimum working distance of just 20mm from the front element. Focusing from 2:1 macro to infinity at f/14, it needs a lot of light, yet provides a unique perspective — adding a disorienting effect to the scene.

Maddox-Upshaw also deployed the Laowa for some POV shots in later scenes. “You can get super macro, and then, when you pull out, it will rectify itself so it doesn’t stay macro,” he explains. “Once you rack focus, it flattens out the field of view. You see stuff that goes in and out, and Faraday never went ‘weird fisheye’ at all. That’s what’s cool about this lens.”

The cinematographer made further creative use of the Laowa in Episode 4, when Faraday accompanies Clive Flood (Laurie Kynaston) to his grandfather’s cabin studio to listen to a “music sphere” that Newton left behind. Clive is the bad boy in the Flood family: derelict, and a disappointment to his icy mother. In this scene, he reacts to Faraday’s questions about his Tourette-syndrome tics by blowing smoke from his crack pipe into the alien’s face.

“Faraday has never ingested this substance before,” Maddox-Upshaw notes. “We needed him and the camera to go over the top. When it came to seeing him flip out because of the contact high, I went back to the Loawa. I pumped in as much light as I could, because I wanted to get close and follow him around. And because it’s a macro lens, that helped distort the world a bit.” But shooting extreme close-ups with a 16" probe lens is tricky: “It’s kind of tough because the operator has to be careful not to stick the actor in the eye.” The cinematographer also altered the shutter angle to increase the sense of weirdness, and shot with the Sony Venice in Rialto mode to lend his camera-movement additional flexibility.

The scene continues with Faraday listening to the music sphere. To Clive, the sounds are “pretentious noises,” but Faraday recognizes it as a message from Newton to his wife back on Anthea. Newton is lamenting the fact that there will come a time when he can no longer remember her, “because he will become more human than Anthean in his experience on Earth,” Maddox-Upshaw says. As Faraday translates from the Anthean language, the camera pivots to a mirror. Newton stands beside him in the reflection, reciting the same words.

Due to actor Nighy’s schedule, he and Ejiofor had to be filmed separately for the scene — four months and many miles apart. “We shot Chiwetel in June in a cabin built by production designer James Merifield at a manor in the English countryside, and then we shot Bill in October against greenscreen inside a shut-down college campus. We matched the lighting and it worked out. It’s one of those things I’m very proud of.”

The show’s overarching visual design sets up two contrasting worlds: one grounded in love and family and the other a colder, sharper reality. “It’s about juxtaposing intimacy against the institutional nature of the forces coming after Faraday and Justin Falls,” Maddox-Upshaw says. Intimacy is present within the Falls family. All their scenes were filmed with new, as-yet-unnamed prototype spherical lenses from Panavision. Meanwhile, scenes featuring CIA operatives and the Flood family were captured with Panavision G Series anamorphics, which presented a sharper, harsher world: “They were great in terms of sharpness and their flaring, which I felt was not as intimate as the sphericals.”

The show was shot in 6K to retain image quality for the 2.39:1 extraction from the spherical footage. “We created different LUTs after having the spherical lenses manipulated by [ASC associate] Dan Sasaki at Panavision,” Maddox-Upshaw adds. “They were designed to complement our approach to skin tone, warmth and flares.”

The contrasting looks of the worlds were also reflected in the lighting. “I tried to make sure there was always a level of warmth when it came to the Falls family. I was a bit more aggressive in mixing colors, and I used stronger sun backlight, in part because the scenes were in New Mexico. After that, you can figure out what’s cold and institutionalized in these other storylines.” The production shot exteriors for these scenes in Almería, Spain, while the rest of the show was produced outside London.

To pass the baton to the other cinematographers on the series — Adam Gillham for Episodes 5, 6, 9, and half of 10; Balazs Bolygo, BSC, HSC, for Episodes 7 and 8 — Maddox-Upshaw supplied a look bible detailing his work. “I created a PDF that went through about six iterations of the visual arc and design for the show, and then Alex shaped it with his ideas. Once we got to a spot we both really liked, we presented it to Showtime.”

Also, key to maintaining a consistent look across 10 episodes were gaffer Wayne Shields and key grip Robert Fischer, who worked on the entire show. As new filmmakers cycled through the production, “they kept people on point,” Maddox-Upshaw says.

Kurtzman and Maddox-Upshaw didn’t meet in person until the cinematographer landed in London for prep, and their Zoom conferences dove-tailed smoothly into a close in-person collaboration.

“If you ever find a collaborator [with whom] it’s easy to create moments, try to hold onto them,” Maddox-Upshaw advises. “Value that relationship.” Like him, Kurtzman was nervous at the outset about doing this update to the classic sci-fi feature. “It was like, ‘Let’s jump together,’” the cinematographer says of their collaboration. “It was very Thelma & Louise: You go off the cliff together, and neither of you holds back.”