Manaki Film Fest: Focused on Motion Pictures

The 45th International Cinematographers’ Film Festival Manaki Brothers celebrates artful camerawork amidst a backdrop of history.

Photos by the author

Macedonia might be most familiar as a storied place of the distant past. Territory of this ancient kingdom is now shared between North Macedonia and Greece, which together boast a history replete with great names of the ancient world. Coincidentally, the film business sometimes finds people craving to be remembered, in which context keeping a name like Alexander the Great current for 2,300 years feels like a standout achievement.

It might take more than a star in the sidewalk to do that, but Macedonia has those, too. The city of Bitola, in the southwestern part of North Macedonia, near the border with Greece, keeps a moment of camera history among its streets of century-old buildings. Širok Sokak (literally “Wide Alley”) is a pedestrian thoroughfare of pavement cafes and independent businesses boasting a promenade celebrating cinematographers from the 1910s to the present day. Possibly the two most prominent stars are located outside the Кино Манаки (Kino Manaki), an elegant recreation of an early-20th-century cinema.

The building is a namesake of pioneering filmmakers Milton Manaki, BSC and his brother, Yanaki (or Janaki) Manaki, BSC, who created the structure’s predecessor in 1923 as an early attempt at vertical integration in the movie business. Their first film, The Weavers, was a 60-second short featuring their grandmother at her spinning wheel. Shot in 1905, it might represent the earliest moving images photographed in the region. The Manaki brothers went on to record events of that turbulent time, in that turbulent place, losing footage to a bombing and their cinema to a fire over the following decades.

Surviving footage of grandmother Despina is part of a montage shown to open the International Cinematographers’ Film Festival Manaki Brothers, the 45th edition of which recently took place on Sept. 21-27. Held annually in Bitola, the event holds claim to being the oldest cinematography-specific festival in the world, and has attracted talent to its panel of judges including — for 2024 — John Seale, ASC, ACS; Agnès Godard, AFC; Cevahir Şahin; Birgit Guðjónsdóttir, IKS, BVK; and Macedonian writer-director Vladimir Blazevski. Each year, the festival presents a series of awards named Camera 300, after the serial number of the Manaki brothers’ first 35mm Bioscope.

This year, the Širok Sokak sidewalk constellation expanded to include Seale; Chris Menges, ASC, BSC; Walter Carvalho, ABC; and Sven Nykvist, ASC, FSF.

The latter was the recipient of the festival’s first-ever Lifetime Achievement Award, and this year the prize went to Bruno Delbonnel, ASC, AFC. He and Jolanta Dylewska, PSC — who was honoured in the category of Outstanding Contribution to World Cinematic Art — received their awards from North Macedonia Prime Minister Hristijan Mickoski during the festival’s opening-night celebration.

Since 2021, the festival has been directed by Simeon Damevski, visible to 2024 attendees as an occasional blur as he sprinted through a clearly packed schedule. Arriving in Bitola in time for the opening, one might have met Damevski for just long enough to recognise a man clearly in his element. Working with a core team of just 13 and a cadre of dedicated volunteers, Damevski’s workload cannot have been anything other than extreme.

He took a rare moment of downtime to talk at the Hotel Epinal. Standing at the entrance to Širok Sokak from the town square, venue for the red carpet opening, the Epinal’s airy atrium restaurant became the default hangout for peckish festivalgoers. “I was six years old when I had my first audition,” Damevski said. “My father was one of the biggest actors in my country, the former Yugoslavia. I was in love with films and I wanted to be an actor.”

After living and working in America for 20 years, he returned, and his involvement in the festival came unexpectedly. “I'm a member of the Macedonian Film Professionals Association,” Damevski explained, referring to the body which organizes the event. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the fest was without a director just two and a half months before it was to start, and Damevski found himself well-placed to intercede: “I’d wanted to make a big film festival earlier, and I had a whole plan and everything.”

He threw himself into the project and has been asked to return each year since. The motivation for both he and the government is clear: “The festival attracts the eye of the world. It would be good for the country, and for producers who would come to shoot. I'm bringing cinematographers. They know producers. They may have an idea.” If the guest list is a measure of success, the country has every reason to be satisfied.

The Macedonian region is sometimes called the Ottoman Balkans, and in early October 2024 those mountains basked in sunshine the rest of Europe already seemed to have abandoned. The journey from the capital Skopje takes in winding roads through the mountains to the cypress-dotted plains north of the border with Greece, where quarries of the country’s pure-white marble scatter the hillsides with bright spots. A smart new highway is under construction, though, as so often, the newer, faster option might give something away in character.

Cinematographer and fest jurist Birgit Guðjónsdóttir travelled a relatively short distance from Berlin to encounter an unexpected sense of familiarity in Bitola. “It has maybe something to do with my grandparents from the Austrian side,” she said. “I'm an Icelandic Austrian living in Berlin, but my grandparents from the Austrian side came from Yugoslavia. So, as for me, I have some Slavic blood in my veins. I feel a little bit at home because it reminds me of Yugoslavia… If you come to Bitola, there are the same houses… and also parts of it like they are in Austria.

“When I first heard about this festival, maybe 10 or 15 years ago, I thought, ‘Wow, it's a festival for cinematography. You have to go there.’”

The opportunity to speak to other cinematographers, and particularly to people at all levels of experience, is something Guðjónsdóttir finds particularly valuable. “Everybody is talking to each other,” she said. “I would recommend people come here because it's such a wonderful energy. We are here like a family… we are not divided into groups of who is important, who is less important.”

The festival screened 65 films, with 12 international entries in the main competition including Black Dog from China, Chronicles of a Wandering Saint from Argentina, Evil Does Not Exist from Japan, and The Girl with the Needle from Denmark. That international flavour, Guðjónsdóttir points out, inevitably affects interpretation, as with Black Dog. “A young man coming out of prison is a story we have seen so many times, but we as Westerners can't, don't, know is what it means for China. They have to go through the censors, so there's a much bigger meaning behind it.”

Bitola’s Cultural Centre boasts a capacious 847-seat auditorium which drew many a sotto-voce “Wow” from people entering through its comparatively modest lobby. It provoked, Guðjónsdóttir says, a realization that is paradoxically so familiar that it’s easily forgotten. “Two of the films I saw before, and I thought, ‘Okay, do I want to see them again?’ And then I said, ‘Okay, to be fresh in my judgement… one which I had seen on the laptop, I saw now on the big screen.’”

That, Guðjónsdóttir feels, should not be a surprise — though it sometimes is, even for experienced people. “I’m a cinematographer. I know the big screen is different, but sometimes because you're a cinematographer you think, you know, you can adapt. And you can't. Some of the films, you have to see them on the big screen. You don't see, as much, the surroundings. You are focused on the story. And it's a huge, different impact.”

The opportunity to engage with everyone from beginners to senior society members is a high point for Guðjónsdóttir. “I will remember all the great talks to all the wonderful DoPs, all the wonderful colleagues who are here. To sit with John Seale on the jury and to have talks with Bruno, it's just so wonderful. I've never met Agnès Godard, and she's been my hero for all my career. She's done such great, wonderful films, and now we're sitting side by side in the jury. I’ll try to come back because I love talking to colleagues.”

Accessing Macedonia from much of western Europe requires a simple relay via Zurich or Vienna, although John Seale traveled for more than 30 hours — enduring a brain-bending shift in circadian rhythm — en route from Australia. “I'm going to sleep at the drop of a hat,” Seale confessed during a conversation crammed between the screenings which form the core duties of a festival jurist. The fact that Seale was available to be there might be due to a recent step back from a long career at the high end of camerawork.

We talked in the Officers’ Hall, a grand and recently renovated ex-military building at the southern end of Širok Sokak. With stained-glass windows scattering chromatic light across polished wooden floors, it recalls an establishment of religion or an ancient library. It is an almost reverential place, a far cry from the graffiti’d hulk which existed at the beginning of the 2010s. The hall’s restoration is talismanic of the growing fortunes of the region.

Seale’s thoughts were perhaps provoked by being so far from home. “I'd spent so much of my life traveling,” he mused. “At other people's command, you know? And I sort of got to the stage where I just wanted my life to do what we wanted to do when we wanted to do it. I was sitting in a new little car, revving the engine. I was going to buy it to retire and drive around Australia, or whatever. And I saw my wife answer her mobile, and she's looking at me… and I just knew, because I'd heard on the grapevine, about Fury Road getting going.”

That was 10 years ago. After Mad Max: Fury Road, Seale reunited with director George Miller one more time, for the fantastical Three Thousand Years of Longing. “We did a survey from London to Istanbul and Sydney. And it was during that trip that George asked me, would I go on to Furiosa? And I said, ‘Oh, George, I can't do it.’ He tried again, and he was lovely, but I'd really set my mind.”

Festival jury duty might seem like a comparatively restrained pastime, although Seale’s time in Macedonia was rarely his own. Even during the day, seminar attendees were often packed into a standing-room-only Kino Manaki. Seale’s thoughts, possibly guided by his surroundings, turned to history and progress, and particularly to an anecdote regarding Anthony Minghella mentioned in a talk that day.

“It was a lovely moment,” Seale recalled, thinking of his collaborator on the features The English Patient, The Talented Mr. Ripley and Cold Mountain. “Anthony Minghella was absolutely brilliant — a writer and director — and developing like crazy until he very sadly passed away [in 2008]. But in a comment he once made to a young man about his short movie, [Minghella said], ‘Okay, you've conquered the technicalities of filmmaking, now put two actors against a brick wall, just a plain brick wall, and make me cry.’ I thought, ‘That is the most incredible piece of clinical thought on what is a film, and what you can do with it.’”

Events at the festival included several moments of similar profundity. The “IMAGO Master Chat” packed the Kino Manaki almost beyond capacity for an event featuring Seale alongside Christian Berger, AAC, BVK and Dante Spinotti, AIC, ASC. Another featured Delbonnel, and, at the time of writing, the world was acclaiming his camerawork alongside Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki, ASC, AMC on Apple TV’s Disclaimer. The term “TV series” probably does Disclaimer an injustice, though like much of Delbonnel’s cinematography, the production is imbued with a particularly strong sense of place.

Delbonnel said that he regularly gives thought to his environment. “So, we're in Macedonia now,” he began, glancing around Bitola’s Goce Delchev Square. “Macedonia was Yugoslavia. They had [President Josip Broz] Tito, the Socialist kind of system. I'm French. So, my history compared to a Macedonian cinematographer is totally different. You always come with your background in some ways. And I'm kind of against globalization, in some ways, in that regard.”

Discussing Amélie with Delbonnel, who has discussed it a lot, can seem ungenerous to his body of other work. Still, with a standing-room-only screening and panel at the Kino Manaki, it seems to be a cross the cinematographer will have to bear. Either way, it stands as an example of his concepts of place and culture. “I live in the neighbourhood where we shot Amélie, and [director Jean-Pierre] Jeunet moved to Paris, so we knew every corner of the city. And even the attitude — Parisians are pretty rude, like the New Yorkers. So I understand more New Yorkers than I understand the Londoner in some ways!”

Delbonnel spoke soon after a screening of the determinedly historic drama The Girl with the Needle, shot with great deliberation to recall early still photography. Sitting under the gimlet-eyed statue of Milton Manaki and his comparatively primitive Camera 300, Delbonnel offered a warning about a cinema borne of post-scarcity equipment. “The danger for me is to be seduced by the image you see on screen. You push the [record] button on a digital camera and you have an image. You say, ‘Wow, that’s interesting,’ but you haven’t done anything. It pushes you away from what you have in mind. It tells you what it is. It's a big topic, being seduced.”

Consideration of places, the people who inhabit them, and the things those people do with cameras seems only appropriate under the circumstances. “There was only one Fellini in the world,” Delbonnel said. “There was only one Kurosawa. There was only one John Ford, or Tarkovsky. They are all part of their history. And the way they tell stories is part of their background.”

Delbonnel’s thought reminds us that the Manaki Festival itself is powerfully underpinned by one person: Simeon Damevski, whose current term as director expires this year. “If they re-elect me again,” he said, “I will gladly do it because all these people I've brought are expecting from me to continue growing the festival and doing what I'm doing.”

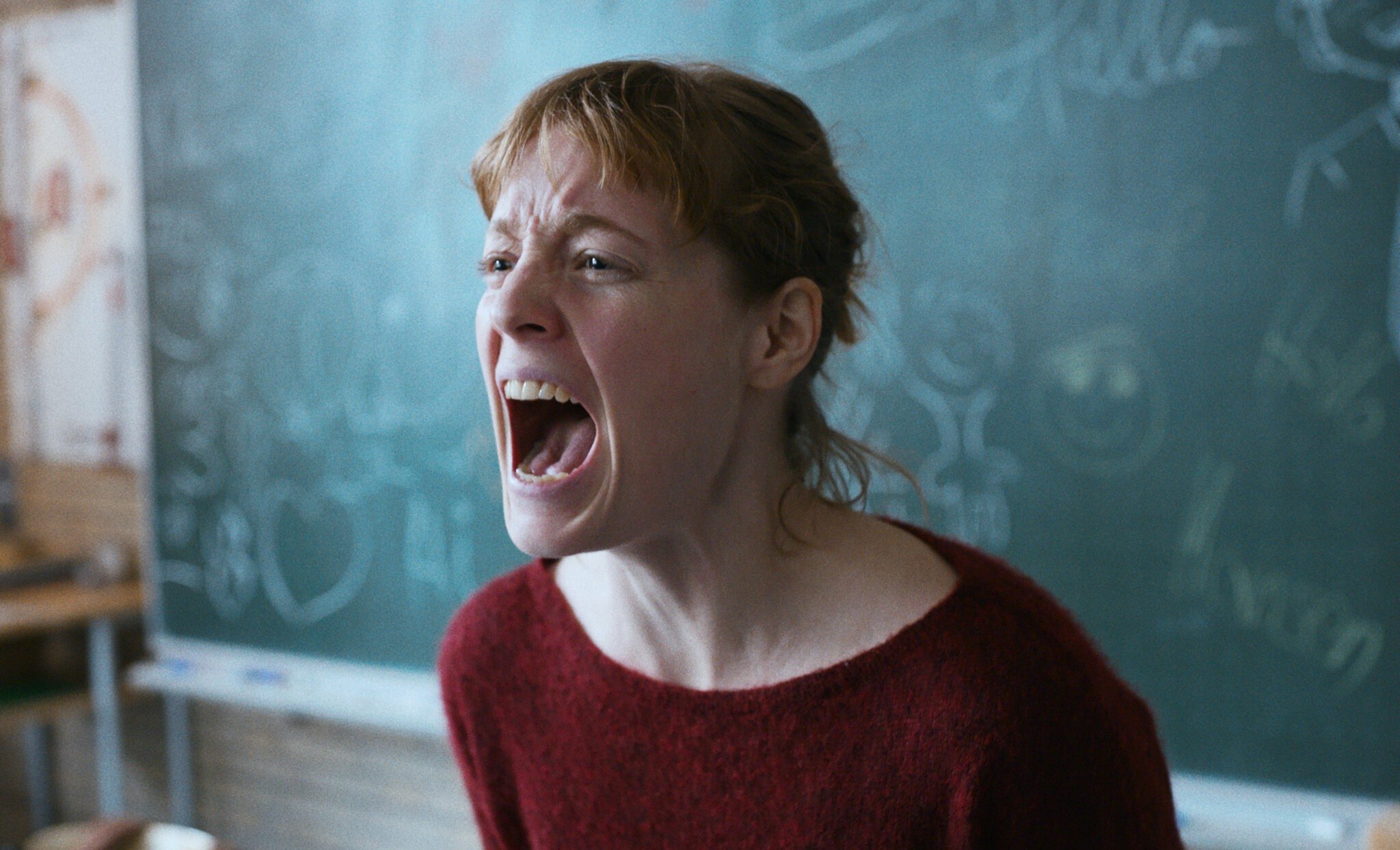

Judith Kaufmann, BVK might agree: The 2024 Golden Camera 300 Award went to her work for The Teachers’ Lounge. The Silver Camera 300 went to All We Imagine as Light, photographed by Mumbai-based Ranabir Das, and the Bronze to The Promised Land, the work of Danish cinematographer Rasmus Videbæk.

Crucially, the festival lands well with all the right people, as Damevski noted, “The person who gave the award to Bruno is the prime minister of the country. So, you see how big this thing has grown up.”

As departing attendees gathered by Milton’s statue to meet the airport shuttle one summery Balkan morning, it seems likely more will visit what’s being described as one of the world’s more personal and involving festivals. The Manaki brothers could hardly object — everything they did seemed calculated to attract moviegoers. To maintain that tradition for over 100 years seems fitting in a place which thinks of centuries as the small change of history.