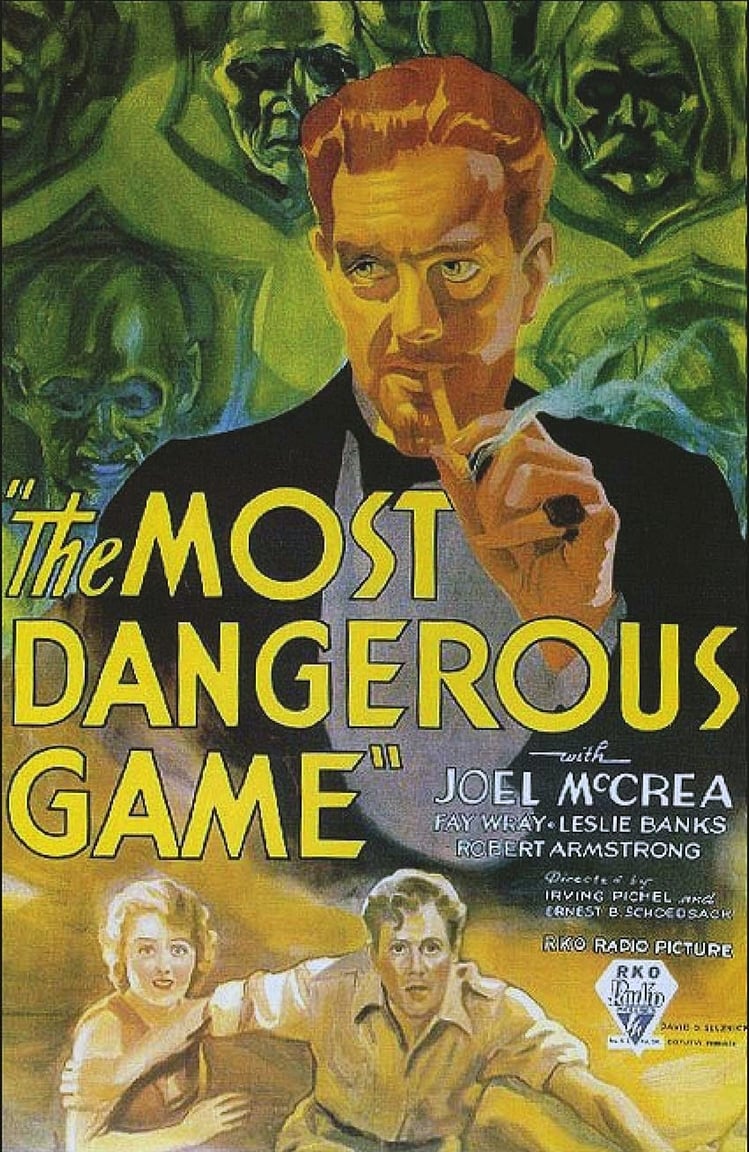

Hunting The Most Dangerous Game

Looking back on the creative — yet budget-conscious — production of this influential Pre Code 1932 thriller, which has been remade numerous times since.

This in-depth look at the making of Beetlejuice first appeared in American Cinematographer's September 1987 issue. For full access to our archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.

Looking back on the creative — yet budget-conscious — production of this influential Pre Code 1932 thriller, which has been remade numerous times since.

An enormous Gothic door fills the opening frames of The Most Dangerous Game. The call of a distant hunting horn is heard as the camera moves in to examine the massive door knocker. It is fashioned as a centaur, its brute face twisted in agony, a metal arrow protruding from its breast. In hinged arms the creature holds the body of a girl whose torso forms the hammer. A man’s hand reaches into the frame, takes hold of the girl’s waist, and lets the hammer fall. Music builds as the main title dissolves in: Radio Pictures Presents A Cooper and Schoedsack Production…

Here was good news for the many 1932 moviegoers who were bored with the overly talky talkies then dominating the screen. It meant that two men who always made moving pictures were back.

Merian Coldwell Cooper left his Jacksonville, Florida home as a youth and became, in rapid succession, a newspaperman, an Annapolis midshipman (who didn’t graduate because he went “over the hill” to see a girl), a trooper chasing Pancho Villa along the Texas-Mexico border, and a much-decorated combat pilot of World War I. He refused the Distinguished Service Award because he didn’t want to be singled out from his buddies. He became chief of the Polish Air Force during the Russo-Polish War, and his escape from a Russian prison after being shot down by Budenny’s Cossacks made international headlines. He continued to attract attention as author, explorer, movie producer and airline executive.

Ernest Beaumont Schoedsack ran away from his Iowa home when he was 14. Within a few years, he was F. Richard Jones’ top cameraman at the Mack Sennett Studio, then a combat photographer for the Army Signal Corps. Later, he led rescue missions while cranking a camera for the Red Cross during the Russo-Polish and Greco-Turkish conflicts. He met Cooper in Vienna in 1918 and again in Singapore in 1922. During an African expedition, they formed the filmmaking partnership that took them into the Bakhtiari Mountains of Persia, where they filmed the celebrated “natural drama” Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life (1925). They made Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness (1927) in the jungles of Laos and shot part of The Four Feathers (1929) in East Africa. On his own, Schoedsack photographed Rango (1930) in the Sumatran wilderness. Each of these films was made under incredibly difficult, dangerous conditions.

The stocky, hard-nosed Cooper became executive assistant to RKO Radio’s new vice-president in charge of production, David O. Selznick, late in 1931. There was an understanding that Cooper would also be permitted to develop productions of his own. The company owned the former FBO Studio in Hollywood, which they re-named The Radio Studio, and the old Pathé lot in Culver City. Founded in 1929 on the eve of the Depression, the brave new company was in financial straits almost from the start.

Schoedsack returned to Hollywood in January 1932, after several months’ location work in India for Paramount’s The Lives of a Bengal Lancer. Exasperated by a long wait for studio chiefs to approve a final script for the project (eventually to be directed by Henry Hathaway in 1935), he asked to be released from his contract.

Immediately, he joined Cooper at RKO and began pre-production work on what was to be the first all-talking Cooper-Schoedsack collaboration, an adaptation of Richard Connell’s O. Henry Award-winning short story The Most Dangerous Game.

Schoedsack — standing a lean 6’, 6” — was Cooper’s physical opposite. The partners were equally dissimilar in personality, Schoedsack epitomizing the “loner” who shrinks from publicity, while Cooper was contrastingly flamboyant and loquacious. Both men possessed a love of adventure — the more dangerous the better — and an appreciation of the artistic, the dramatic and the spectacular. They divided their work according to individual abilities and preferences, their differences contributing as strongly as their similarities to their excellence as a team.

Connell’s 1924 short story tells of General Zaroff, late of the Czar’s army, who has only one passion: the hunt. The hunting of brute animals no longer offers the challenge he wants, however, so he decides to create a game worthy of his mettle. Retiring with a trusted Cossack servant to a small Caribbean island, he stocks his game preserve with human beings, the survivors of shipwrecks Zaroff arranges by tampering with the light buoys that mark a channel between treacherous reefs. When famed hunter Sanger Rainsford falls overboard from a pleasure yacht and is cast upon Zaroff’s shore, the madman conceives his greatest hunt. Rainsford wins the game, kills Zaroff in a duel of swords, and succeeds him as keeper of the preserve.

This masterful tale has all the elements of a first-rate film thriller save one: there is no “love interest.” To compensate for the loss of the purely masculine concept and the caustic ending of the original, Zaroff was made even more horrid. “He cannot love until he has known the thrill of the hunt with a human being as his prey,” Cooper explained. “Such an atavistic creature is the man who by his savage instincts dominates the most dangerous game.”

As for casting a woman into the lupine hunt, Cooper had no qualms. “Woman has retained, fortunately, the fighting, dominant blood of the savage,” he described. “She would have perished as a distinctive individual long ago had it not been for her savage strain which has always given her the impetus of fighting for her own rights. This quality can be found in the most fragile of women. For a long time I always thought that ‘the most dangerous’ game naturally would be one in which a woman was involved.”

James A. Creelman, a noted screenwriter of adventure yarns, succeeded remarkably well in delineating this complex, highly original monster.

Another story change demanded by the producers was to make Rainsford the victim of a planned shipwreck rather than a man overboard. This situation, like many in even the most fantastic of Schoedsack and Cooper’s films, was suggested by personal experience. They were members of the ship’s company of the Wisdom II 10 years before, when Arab wreckers decoyed the ship onto a reef by disabling a lighthouse.

The New York office put a damper on their plans to make a spectacular production when it decreed a budget of only $202,662 and a three-week shooting schedule. In an attempt to stay within this inadequate figure, Cooper and Schoedsack pored over the script, seeking ways to eliminate expensive details in order to apply the money where it would show best on the screen. An example is a reworking of the shipwreck sequence, which would have cost a great deal more had it been staged as originally planned. Schoedsack wrote this note to production supervisor Val Paul on May 4, 1932:

Mr. Cooper and I have discussed and approved a change in the yacht sequence which should result in considerable economy, while improving and adding realism to the wreck with a more modern and convincing method...

At the instant that the ship scrapes bottom, we leave the interior of the dining salon as the set rocks over, but before the water enters. We cut to the flash on the bridge as the officer discovers the water has reached the boilers. We cut to a miniature explosion of flash powder on our miniature hull and instantly dissolve to a series of overlapping and rapidly dissolving flashes such as falling wreckage (all in close-ups), a man being washed along a deck, falling spars and gear, drowning sailors, hissing steam, etc., accompanied by screams, crashes and the roaring of water. Over all will be exposed flashes of foaming and churning water, and the last flash might be the last of the masthead disappearing under the water. Inasmuch as these scenes are fast and impressionistic, I think they could be very cheaply made, or perhaps a great many found in stock. At the end of the series, we dissolve to the scene of the boy in the water, as in the present version.

As you will see, this lineup eliminates the following items:

1. Building salon set in tank, with water dumps.

2. Possibly eliminate rockers on both bridge and salon.

3. Eliminates deck set in tank entirely.

4. Simplifies miniature yacht work to some extent.

5. Eliminates costume changes for extras in cabin.

Later, Schoedsack eliminated nine actors from the already small cast. Dropped from the passenger list of the doomed yacht were screen veterans Walter McGrail, Cornelius Keefe, Creighton Hale, Theodore Von Eltz, Christian Rub and Alfred Codman, plus three young hopefuls: Leon Waycoff (later Ames), Creighton Chaney and Ray Milland.

Shooting began May 16, 1932, on the jungle set, and ended June 17. Final cost was about $16,000 over the original budget. Two Russian language advisors helped Creelman write the dialogue and another stayed on the set to see to the accuracy of Zaroff’s frequent lapses into Russian dialogue.

Henry W. Gerrard, ASC was in charge of the studio photography, seconded by Robert De Grasse, ASC.

A Canadian war hero then 38 years old, Gerrard had been a leading cinematographer at Paramount and was on his first assignment for RKO following his return to Hollywood from a year of shooting in England for MGM and British International. He was on first call for any and all pictures Katherine Hepburn made at RKO, and his later credits included Phantom of Crestwood, Blind Adventure, Little Women, A Little Minister and Of Human Bondage before his untimely death in November of 1934 from complications during surgery for appendicitis.

De Grasse hailed from New Jersey and had begun as an assistant cameraman at Universal in 1916. He had been a director of photography since 1921, but with the coming of sound in 1928, he asked to be demoted to operator status because he felt intimidated by the new techniques. Resuming as director of photography in 1935, he shot most of Ginger Rogers’ RKO pictures, as well as Break of Hearts, The Leopard Man, The Body Snatcher, The Window, The Miracle of the Bells and nearly 80 others. Later working in television, he would shoot numerous episodes of The Danny Thomas Show and The Dick Van Dyke Show, among many others. He died in 1971 at the age of 70.

On second camera, De Grasse oversaw photographing the entire picture directly alongside Gerrard from a very similar angle, resulting in a second original negative that could be sent to Europe for overseas distribution use. The poor quality of dupe stocks at the time required this additional photography.

Nicholas Musuraca, ASC — then an all-purpose cinematographer at RKO — photographed the location scenes, including some glass shots and process plates. Musuraca, who died in 1975, had been a cinematographer since 1913. During the 1940s he became the most celebrated “mood and atmosphere” expert at the studio and today is widely regarded as a father of the film noir style.

Rounding out the first camera team were assistant Willard Barth and operator Russell Metty — who would go on to become an exceptional ASC cinematographer himself, with credits including Bringing Up Baby, All That Heaven Allows, Touch of Evil and Spartacus (for which he won an Academy Award).

“Our jungle set was all on Stage 12 at Pathé,” Schoedsack recalled. “We moved the plants around different ways and used glass shots to get different views.”

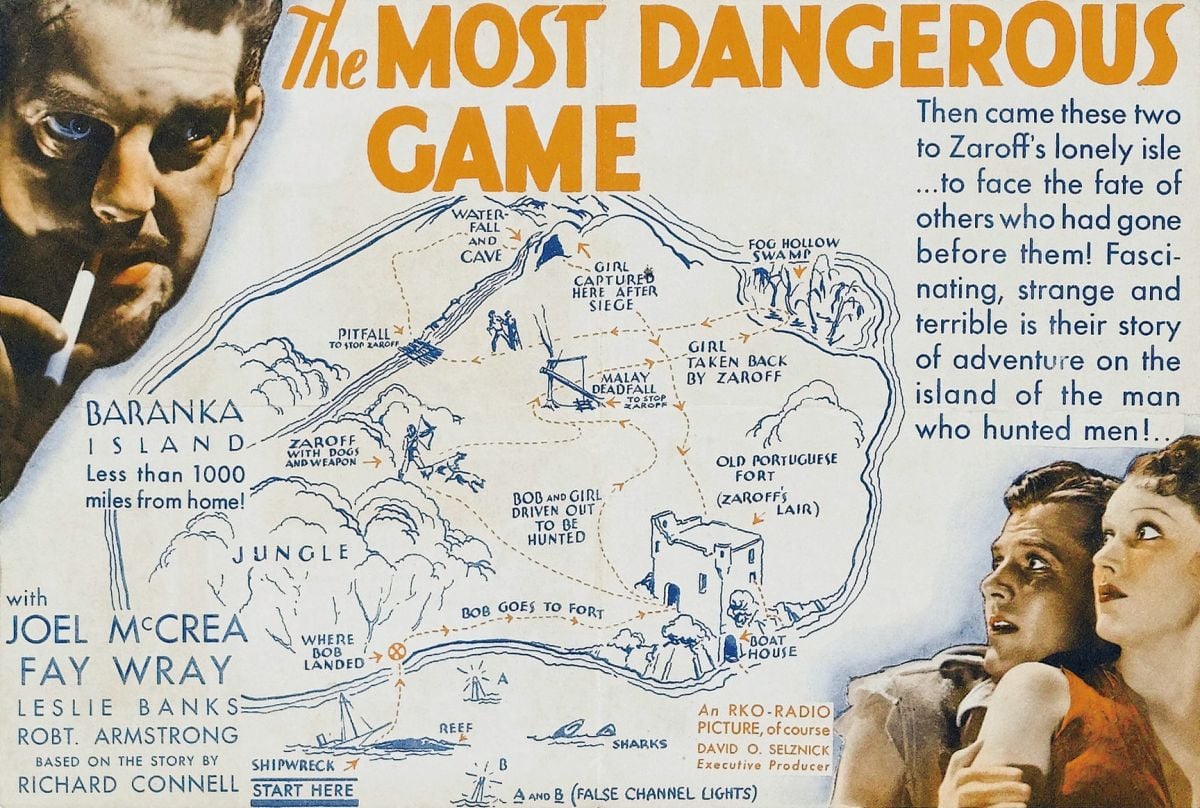

The swamp was built in a tank 60 feet long, 35 feet wide and 15 inches deep, with the slopes built up on ramps. The rest of the jungle included a trail with a Malay deadfall, a cave, a crevasse bridged by a huge log, cliffs and ledges of artificial rock, and a portion of the chateau of Zaroff built at the edge of the undergrowth. The waterfall and rapids sets, composited by glass art and the Dunning travelling matte process with both real and miniature cataracts, was built on Pathé Stage 14. Byron Crabbe’s glass paintings of the chateau were matted in with live player action and seascapes via the Dunning process. Kenneth Peach, ASC, was process cinematographer. Optical effects were added in postproduction by Linwood Dunn, ASC.

Exteriors of the chateau and its courtyard, yacht interiors and the miniature and process shots were created on Radio stages 1, 3 and 9. Scenes of the men in the water following the shipwreck were shot in a tank at Pathé, where stuntman Gil Perkins and a law student from Hawaii, Buster Crabbe, executed the stunt falls. Crabbe, who received $5 for his day’s work, won the Olympic Free Style Swimming competition the following year and embarked upon a long acting career.

Location work was minimal. Stuntman Wes Hopper, doubling as Rainsford, swam ashore on a rocky beach near San Pedro.

Glass paintings by Mario Larrinaga gave the scenes an ominous night sky and supplied buoy lights. Views of the cove from a chateau window were made from cliffs near the present site of Marineland of the Pacific. Other clifftop scenes by the sea were filmed at Redondo.

Cooper was delighted with the jungle set because it fit into his plans for what was to be the next Cooper-Schoedsack venture, King Kong. On the strength of illustrations made by Larrinaga and Crabbe under the supervision of technical expert Willis O’Brien, he convinced the RKO heads to allow him to produce a test reel for Kong. Cooper became a frequent visitor to the Dangerous Game set, bringing with him Creelman, a separate camera crew, some tough-looking stunt extras and a young and untried contract player named Jacques de Bujac (soon to be renamed Bruce Cabot). Whenever possible, he borrowed Fay Wray and Robert Armstrong, put them into soiled costumes, covered the actress’ brown hair with a blond wig, and put them to work in scenes improvised by Creelman and himself.

Due to this, it has been mistakenly reported since that Dangerous Game and Kong were produced concurrently.

Schoedsack became irritated at his partner’s interruptions. Cabot said the two “argued all the time on that set.” Film editor Archie Marshek remembers that Schoedsack sometimes hid in the editing room when he saw Cooper approaching. The use of these sets in both pictures combine with similarities of directorial and technical style to create a close kinship between the two films.

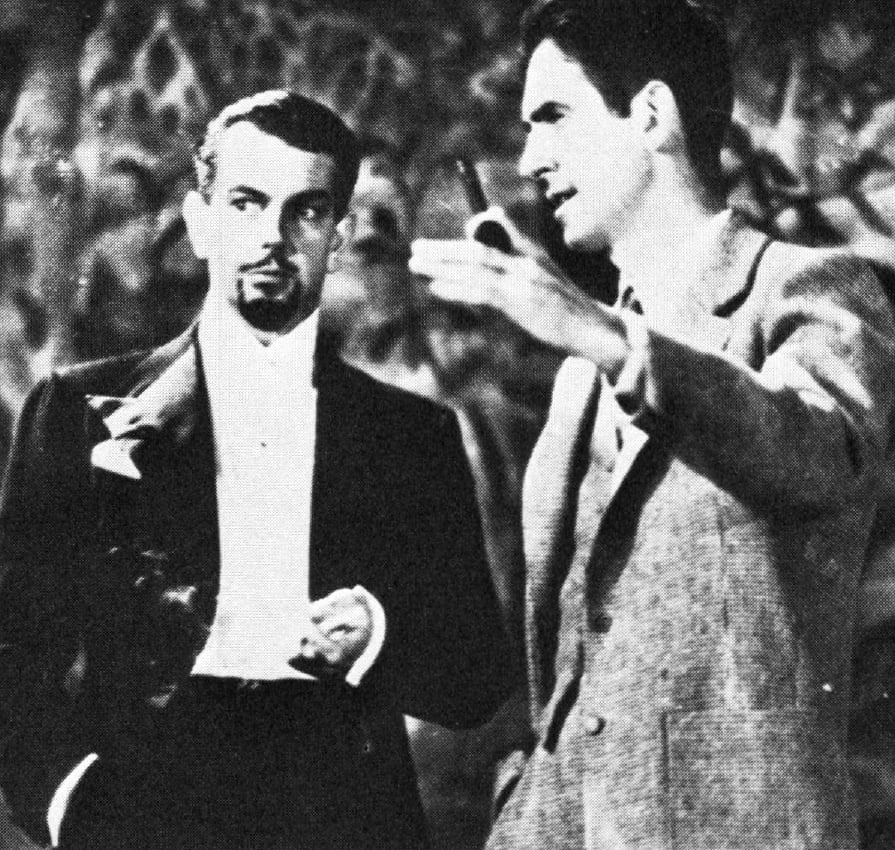

Joel McCrea, who was being groomed for stardom by RKO, was only 26 when he was assigned to the Rainsford role. Arrangements were made to borrow Margaret Perry from MGM. When, however, she proved unavailable at production time, the producers seized the opportunity to hire their friend Fay Wray, who had worked for them in The Four Feathers.The lovely Canadian-born actress proved an ideal leading lady for such a tale of terror.

Robert Armstrong, a stage and screen veteran, began in this picture a long personal and professional association with Cooper and Schoedsack. Noble Johnson, the distinguished black actor, was another alumnus of The Four Feathers. Evil-visaged Steve Clemente was a professional knife thrower described by Schoedsack as “the sweetest little Yaqui Indian in the world.” Brawny Dutch Hendrian was a football star.

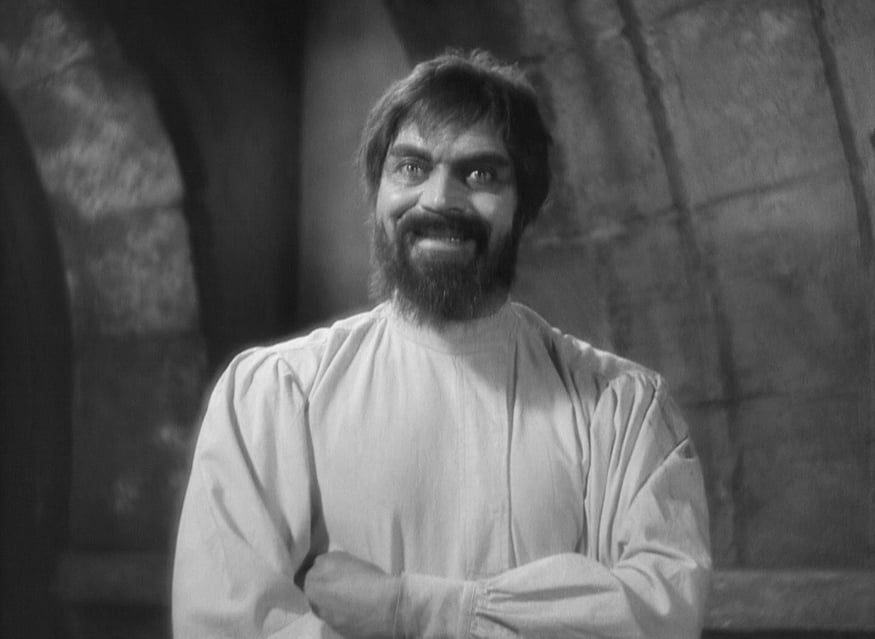

Leslie Banks, an English stage star who had never before appeared in a film, was chosen for the difficult role of Zaroff. He was, according to Schoedsack, “great fun to work with, a fine actor and a great guy with a real sense of humor. His face was badly injured during the war — the left side was paralyzed — which made him interesting to photograph.” Though he was no stranger to heavy drama, having appeared in scores of plays since 1914, Banks was most noted for drawing room comedy. He was starring in “Springtime for Henry” on Broadway when RKO signed him. He subsequently returned to England, where he appeared in numerous films, but he never made another picture in America.

“When I read the script, I felt that nobody would believe it,” Schoedsack said. “I decided the main thing was to keep it moving so they wouldn’t have time to think it over. I didn’t know a damned thing about stage direction, but I tried one thing that worked: I brought a stopwatch to the stage and sometimes I’d say, ‘That scene took 30 seconds; I think we could do it just as well in 20,’ and we’d speed it up that way. The front office was afraid I couldn’t handle dialogue so they sent Irving Pichel over and he just stood behind me and watched.

“I went to a morgue to find out how to pickle human heads. The deadfall came from my experience in Siam and Sumatra. We cheated — we had the tree up on chains, and when we dropped it, we thought the whole stage was going to come down.”

Although the film closely follows Creelman’s script, some of its best moments were improvised. The design of the door knocker and the corresponding motif of a large tapestry were devised during production, as were many striking details of the chase. Schoedsack liked the lines in which Creelman poked fun at his old adversaries, the Russians, such as Zaroff’s comment that “Russians aren’t the best mechanics.” On the other hand, he found the writer somewhat impractical.

“He could concoct some wild ideas,” Schoedsack said. “He decided it would be more scary if Zaroff used hunting leopards instead of dogs. I reluctantly hired a leopard and its trainer from the Selig Zoo, and the cat immediately ran away on the jungle set. People were climbing to the rafters and we spent hours rounding him up.”

Twenty Great Danes, five of which were specially trained by the Hollywood Dog Training School to enact the chase, were then cast: “Some of them belonged to Harold Lloyd, and he didn’t appreciate our blacking them up to make them look fiercer. Once, when we were working on the Fog Hollow set, Leslie came bounding out of the fog, clutching his rear end, and told us, ‘I say, one of those dogs bit me!’ The lady from the training school said, ‘Oh, no, it’s impossible! None of those dogs would do that!’ Leslie said, ‘Well, perhaps it was a cameraman, but something bit me in the ass.’ He was bleeding and had to have first aid and stitches.”

In the opening scene, Bill Woodman’s yacht Sylph approaches notorious Baranka Island, off the African coast. The captain suspects that light buoys indicating a clear channel between the island and the mainland are not positioned correctly. He asks Woodman for permission to take a long route because “there are no more coral-reefed, shark-infested waters in the whole world.” The guests, including a noted hunter and author, Bob Rainsford, are in favor of following the captain’s suggestion, but Woodman refuses.

As the group studies photos of their recent hunting trip, Doc comments: “The beast, killing just for his existence, is called savage. The man, killing just for sport, is called civilized. Bit contradictory, isn’t it?”

Rainsford argues that hunting is as much a sport for the animal. “Now, take that fellow right there,” he says, indicating a tiger he bagged. “There never was a time when he couldn’t have got away. He didn’t want to. He got interested in hunting me. He didn’t hate me for stalking him any more than I hated him for trying to charge me. As a matter of fact, we admired each other.”

Doc demands to know if there would be as much sport in the game if Rainsford were the tiger instead of the hunter. Bob replies, “This world’s divided into two kinds of people, the hunters and the hunted. Luckily, I’m a hunter. Nothing can ever change that, can it?”

The ship strikes a reef. Water rushes into the engine room, causing an explosion that hurls everybody into the sea. Rainsford finds the captain and another survivor clinging to wreckage, but both men are dragged under by sharks. Rainsford swims desperately through the darkness toward a distant light.

Rainsford collapses on a beach, lying unconscious until the sound of dogs barking and the cry of an unidentifiable animal arouse him. He walks towards the sounds and sees, on a cliff overlooking a lagoon, an imposing chateau. He finds a ponderous door, which is adorned with a bronze knocker designed in the likeness of a centaur wounded by arrows. The centaur carries in its arms the body of a woman. When Rainsford knocks, the door swings open. He enters and finds himself in a great hall facing a giant Cossack who only glares menacingly.

“Ivan does not speak any language,” interrupts a man dressed in formal attire. “He has the misfortune to be dumb... Welcome to my poor fortress.” He explains that his chateau was “built by the Portuguese centuries ago. I have had the ruins restored to make my home here. I am Count Zaroff...”

Rainsford says he is the only survivor of the wreck. Zaroff responds that “We have several survivors from the last wreck still in the house. It would seem that this island were cursed.” A huge wall tapestry above the stairway, Rainsford notes, repeats the centaur-woman motif.

The other guests are the beautiful Eve Trowbridge and her brother, Martin. The latter is drinking heavily, to Zaroff’s annoyance. Eve explains that only she, Martin and two sailors survived a recent shipwreck. Zaroff announces proudly that Rainsford is a great hunter.

“Only in your books have I found a sane point of view,” Zaroff tells Rainsford. “We are kindred spirits.”

Martin avers that Zaroff “sleeps all day and hunts all night, and what’s more, he’ll have you doing the same thing... he’s had our two sailors so busy chasing around the woods for flora and fauna that we haven’t seen them for three days.” Eve seems disturbed. Rainsford asks Zaroff what he hunts.

“I’ll tell you,” is the reply. “You will be amused, I know… I have created a new sensation… God made some men poets, some He made kings, some beggars. Me, He made a hunter. My hand was made for the trigger, my father told me. My father was a very rich man, with a quarter of a million acres in the Crimea, and an ardent sportsman… My life has been one glorious hunt. It would be impossible for me to tell you how many animals I have killed… It was here in Africa that the cape buffalo gave me this.” He indicates a deep scar on his forehead. “It still bothers me sometimes.

“One night, as I lay in my tent with this — this head of mine, a terrible thought crept like a snake into my brain. Hunting was beginning to bore me! When I lost my love for hunting, I lost my love of life, of love. I even tried to sink myself to the level of the savage. I made myself perfect in the use of the Tartar war bow… But, alas! What I needed was not a new weapon but a new animal… Yes, here on my island I hunt the most dangerous game.”

Zaroff smiles at Rainsford’s suggestion of tigers: “The tiger has nothing but his claws and his fangs.” Zaroff calls the trophy room “My one secret. I keep it as a surprise for my guests against the rainy day of boredom.”

Martin suggests a hunt: “We’re pals. We’ll have a big party, get cockeyed, and go hunting... “

“A charming simplicity,” Zaroff says aside to Rainsford. “He talks of wine and women as a prelude to the hunt. We barbarians know that it is after the chase, and then only, that man revels. You know the saying of the Ogandi chieftains: ‘Hunt first the enemy, then the woman.’ It is the natural instinct. What is woman, even such a woman as this, until the blood is quickened by the kill? One passion builds upon another. Kill, then love! When you have known that, you have known ecstasy!”

While Zaroff plays the piano, Eve guardedly tells Rainsford that Zaroff has kept her and Martin on the island by pretending his motor launch is out of repair. All windows are barred and huge hunting dogs guard the chateau. Further, “One night after dinner, the Count took one of our sailors down to see the trophy room... Two nights later he took the other there. Neither has been seen since. He says they’ve gone hunting.”

Later, Zaroff sends Eve and Rainsford to their rooms, but delays Martin with conversation. “Don’t worry, sis, the Count will take care of me,” Martin calls.

“Indeed I shall,” Zaroff adds.

Sometimes before dawn, Eve comes to Rainsford’s room to say Martin has disappeared. Rainsford goes with her to the trophy room, they find mummified heads of men mounted as trophies. Another head floats in a jar of embalming fluid. Eve and Rainsford hide as Zaroff and his men — Ivan, a Tartar and a scar-faced Cossack — return bearing the body of Martin. Eve lashes out at Zaroff, who orders her carried to her room. The servants overcome Rainsford and chain him to a wall.

“Come, come, my dear Rainsford, I don’t want to treat you like my other guests,” Zaroff says. “ ...I know what you think, but you are wrong. He was sober enough and fit for sport when I sent him out... You see, when I first began stocking my island, many of my guests thought I was joking, so I established this place. I always bring them here before the hunt. An hour with my trophies and they usually do their best to keep away from me.”

He explains that he is able to get a supply of game because “providence provided this island with dangerous reefs” and he moves the buoys that mark a safe channel. He gives his guests “every consideration: good food, exercise — everything possible to get them in splendid shape... I give them hunting clothes, a woodsman’s knife and a full day’s start. Why, I even wait until midnight, to give them the full advantage of the dark. And when one eludes me, only till sunrise... he wins the game.” He indicates some medieval torture devices. “If a chosen one refuses to be hunted, Ivan is such an artist with those that invariably they choose to hunt... To date, I have not lost. Oh, Rainsford, you’ll find this game worth playing! When the next ship arrives we’ll have gorgeous sport together!”

Rainsford refuses angrily: “You murdering rat, I’m a hunter, not an assassin! What do you think I am?”

“One, I fear, who dares not follow his own convictions to their logical conclusion. I’m afraid, in this instance, you may have to follow them. I shall not wait for the next ship. Four o’clock... the sun is just rising. Come, Mr. Rainsford, let’s not waste time!” He frees Rainsford and gives him a knife. “Your fangs and claws.” Eve elects to accompany Rainsford. Zaroff consents because, “One does not kill the female animal.”

Rainsford is surprised to find the island is “no larger than a deer park.” It is composed of dense jungle, a swamp, and rocky high ground. He sets about building a Malay deadfall, a heavy tree prepared so it will fall on anyone who touches a vine hidden in the path. The couple has only time to hide in a shallow cave before Zaroff approaches.

Zaroff’s foot almost touches the trigger, but he halts, sizes up the situation, and sends an arrow through the vine. After the tree falls, he shoots an arrow into the cave. He tries to taunt Rainsford into coming out. “But surely you don’t think that anyone who has hunted leopards would follow you into that ambush? Very well, if you choose to play the leopard, I shall hunt you like a leopard.” He returns to his fortress.

“You’ve heard him say he’d hunt us as you’d hunt a leopard,” Rainsford says. “That means he’s gone for his high-powered rifle.” Eve runs in terror. Rainsford halts her at the edge of Fog Hollow. “We’ve got two hours until dawn,” he explains. “We’ve got to use our heads instead of our legs.” On higher ground he finds a deep, narrow crevasse, which he bridges with thin branches, leaves and grass.

A sudden uprising of frightened birds announces Zaroff’s return. Eve and Rainsford lure him to the trap. He almost falls, but regains his footing. “Very good, Rainsford,” he calls, “but you have not won yet.” With a half-hour left till sunrise, Rainsford leads Eve into Fog Hollow. They hear Zaroff’s voice: “As you are doubtless saying, the odds are against me. You have made my rifle useless in the fog. You cannot blame me if I overcome that obstacle.” He sounds his horn, which is echoed by an answering horn and the baying of dogs. Ivan and the Tartar emerge from the chateau grounds with several hunting dogs on leash.

Rainsford plants a bamboo spear in the foggy path. The hounds drag Ivan onto the spear, killing him. The dogs race free, followed by Zaroff and the Mongol. Eluding a crocodile, Eve and Rainsford emerge from the swamp. Crossing a gorge via a log, they climb a tree. From a limb, they reach some high rocks. Rainsford decoys one dog into a roaring stream. Backed to the edge of a cliff next to a waterfall, he kills two more with his knife. Another dog leaps upon him, and as man and beast struggle, Zaroff fires. Rainsford and the dog fall into the river far below. Zaroff has won with three minutes to spare.

In his drawing room, Zaroff plays his demoniacal waltz as the Mongol goes upstairs to bring Eve. Zaroff turns to find Rainsford standing in the doorway. “My dear Rainsford, I congratulate you. You have beaten me!”

“You hit the dog, not me. I took a chance and went over with him.”

Zaroff tosses Rainsford the key to the boathouse, then draws a pistol from a cabinet. Rainsord tackles Zaroff. The Cossack servant attacks, but after a vicious fight Rainsford breaks the man’s spine. Zaroff reaches for his war bow, but Rainsford wrests it from him and plunges the arow into Zaroff’s back.

The Tartar appears with Eve on the stairway. He throws a knife, but Rainsford dodges aside and grabs the Count’s pistol. Killing the Tartar, he leads Eve to the motor launch. Zaroff drags himself to a window and watches as the boat comes out of the boathouse. Fitting an arrow to the bow he takes aim. “Impossible!” he gasps, unable to draw the bow. He falls from the window into the courtyard — and the jaws of the blood-mad hounds. The motor launch races toward the horizon at the fade-out.

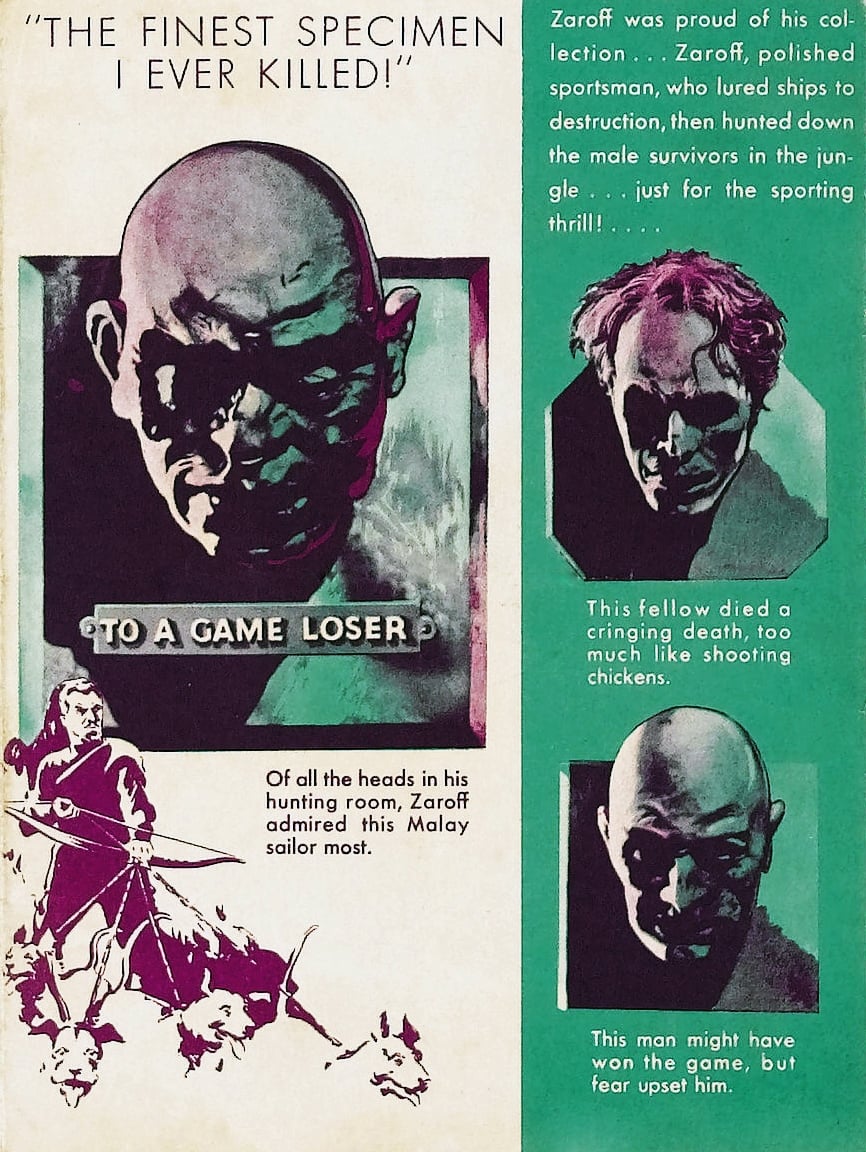

Several scenes which were cut from the trophy room sequence before release possessed a certain grim charm. In one, Zaroff indicates a row of human heads. “Stupid sailors — a thoroughbred dog is worth the lot of them!” he snorts. He shows Rainsford a mounted group consisting of a downed man, full-figure and badly mauled, and two hounds. Zaroff refers fondly to the central subject as “a fine specimen” who “killed my two best dogs — in fact, the ones you see here with him. That’s why I rarely use the brutes. Wound a man and they’ll pull him down before you’ve a chance to make the kill yourself. Even Ivan wouldn’t be safe if they smelled his blood.” When Rainsford remarks at the scope of the tableau, Zaroff explains sincerely, “Well, he deserved the honor. Like you, Rainsford, I never fail to bestow credit where credit is due. Look there, you can see I borrowed an inscription from your own collection.” The plaque reads, “To a Game Loser.”

“Oh, you mustn’t think I feel that way about most of them,” Zaroff adds. “An inferior lot, usually, I regret to say. This chap here — all skin and bones, isn’t he? The emaciated figure is pinned to a post by an arrow. “The foolish fellow tried to run through the swamps of Fog Hollow. We preserved him just as he died, as an object lesson, you might say.”

The film is fabricated in a manner typical of Cooper and Schoedsack. It begins leisurely, building to the sudden and shocking shipwreck, then settles down again to set the stage for the next shocker, the revelations of the trophy room. By this time, there has been an almost clinical elucidation of Zaroff’s s possibly unique form of madness as presented from his own point of view. All of this is splendidly dialogued, but once the chase begins there is a minimum of talk and a wealth of action. There is no pause in the suspense and excitement of this magnificently staged and edited sequence. After Rainsford’s supposed death, the audience is again allowed a moment to catch its breath before the violent climax.

The shipwreck sequence is a striking example of film construction, especially for a product of the early talkie era, when montage most often was determined by the demands of the soundtrack rather than visual considerations. The sequence is composed of 25 shots ranging from one foot (running about three-quarters of a second) to 11 feet (about seven-and-a-half seconds). The assemblage totals only 70 seconds.

Photographically, the film is a tour de force.The most striking visuals are in the chase through the jungle and swamp. The camera is spectacularly mobile at times, keeping pace with the hunted in their flight. Intercut are artistically composed static shots from an astonishing variety of angles. At one point hunters and dogs rush over the camera, appearing as giants looming through the fog. Extensive use of glass art expands the scope and detail of the sound stage jungle. There is even a scene of model birds rising from the jungle, animated by Orville Goldner of the King Kong crew.

Banks easily steals the show from his colleagues. He appears initially as a mincing aristocrat, but when he begins his dissertation on hunting, it becomes disturbingly evident that there is much more to the man than genteel manners and musical ability. Entirely credible is his umbrage at the girl because she considers her brother’s life more important than the hunt, and he is the epitome of savagery as he joyously summons the hounds to the kill.

McCrea appears somewhat more boyish than might be expected of a famed biggame hunter, but his lean physique and natural acting style suit the action. Fay Wray, is, as always, the quintessential lady in distress. Armstrong is amusingly irritating, and Noble Johnson and Clemento supply impressive presences.

RKO’ s overworked musical director, Max Steiner, commissisoned W Franke Harling to compose the score. Harling’s music, fully orchestrated, was delivered in August. An excellent score, it was never used, because Cooper felt it failed to capture the spirit of outdoor adventure and action. “It was like music for a Broadway show,” Cooper remarked. Rather than adapt the existing music, Steiner — himself an operetta and show composer-conductor — worked day and night to produce one of the most exciting of his scores.

Based upon a three-note figure heard initially as a hunting call, the music builds to an ominous theme titled “The Iron Door.” This is developed through numerous variations, including Zaroff’s lilting, yet threatening, waltz. The piano version was performed by Norma Drury, wife of director Richard Boleslawski. Steiner, like Zaroff, saved his real passion for the chase. Here is music to make the heart beat faster as it races along with the feverish action on the screen and underscores each sinister nuance. The climactic scenes are played with musical accompaniment, but without speech other than Zaroff’s barely audible dying word, “impossible!”

“I knew the picture was going to be a classic as soon as I’d seen a few of the dailies,” editor Archie Marshek. recalled. “I took special pains with the cutting. At thepreview there were two places where a lot of people walked out. One was when they saw ahead floating in a jar, and the other was when McCrea broke a man’s back. I put that sound in myself, by snapping a dry stick.”

Schoedsack, who devoted much of his life to the study of music, said he made a conscious effort to compose this film as though it were a symphony. He succeeded admirably. Noting the film’s scant 63-minute running time, one critic called it, “60 of the most exciting minutes of your life.”

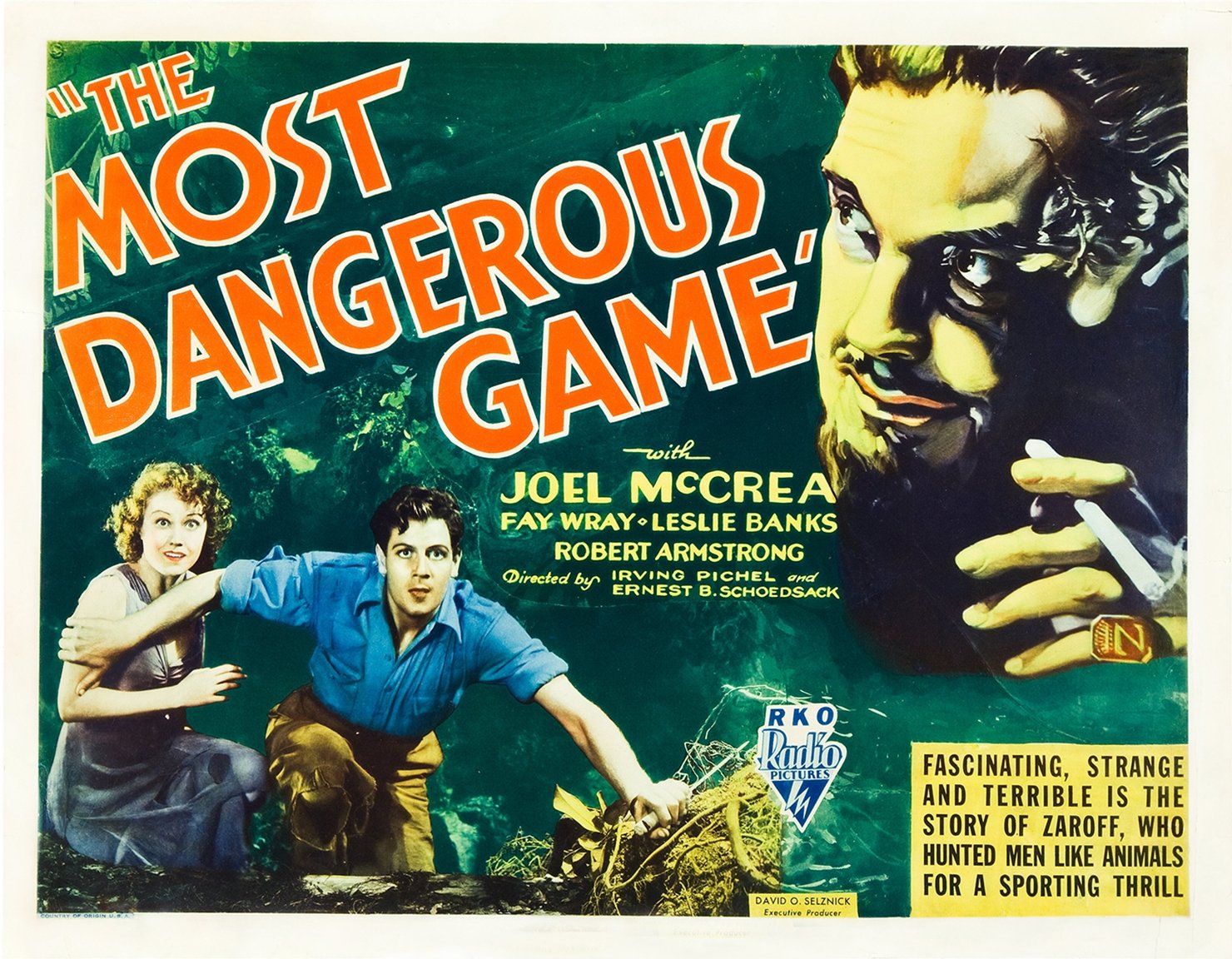

The Most Dangerous Game

A Cooper & Schoedsack production; executive producer David O. Selznick; directed by Ernest B. Schoedsack and Irving Pichel; associate producer, Merian C. Cooper; screenplay by James A. Creelman; from the story by Richard Connell; photographed by Henry W. Gerrard, ASC; music by Max Steiner; settings by Carroll Clark; sound recording by Clem Portman; film editor, Archie S. Marshek; camera effects by Lloyd Knechtel, ASC, Vernon L. Walker, ASC, Linwood Dunn, ASC, Kenneth Peach, ASC; production effects, Harry Redmond Jr.; miniatures by Don Jahrous; animation, Orville Goldner; special properties, Marcel Delgado, John Cerisoli; technical artists, Mario Larrinaga and Byron L. Crabbe; second camera, Robert De Grasse, ASC; location camera, Nick Musuraca, ASC; operative cameraman, Russell Metty; camera assistant, Willard Barth; production supervisor, Val Paul; production managers, Walter Daniels, James Crone; makeup, Wally Westmore; added dialogue, Edward Eliscu, Owen Francis; assistant directors, Percy Ikerd, Edward Killy, Hal Walker; continuity, Marie Branham; technical advisors, Nick Koblinsky, Professor Markover, Alexis Davidoff; set decorations, Thomas Little; pianist, Norma Drury; sound effects, Murray Spivack; process supervision, Dodge Dunning; song, “A Moment in the Dark,” by Carmen Lombardo, Arthur Freed; cutters Del Andrews, Tom Scott; stills, G. E Schoedsack, Seymour Stem; RCA sound system; running time, 63 minutes; released September 9, 1932.

Cast

Bob Rainsford, Joel McCrea; Eve Trowbridge, Fay Wray; Martin Trowbridge, Robert Armstrong; Ivan, Noble Johnson; Tartar, Steve Clemente; Russian Servant, Dutch Hendrian; Captain, William B. Davidson; Doc, Landers Stevens; First Mate, James Flavin; Guest at Radio, Arnold Grey; Guest at Table, Phil Tead; Steward, Clem Beauchamp; Cook, Martin Turner; Helmsman, Charles Hall; Stunt Artists, Gil Perkins, Buster Crabbe, Wesley Hopper.

Editor’s Note: Some biographical information in this story has been expanded and corrected, so the text differs slightly from the original version published in AC Sept. 1987.