Art Amidst Conflict: Never Look Away

Caleb Deschanel, ASC receives his sixth Oscar nomination for this German film based on the tumultuous life of artist Gerhard Richter.

Caleb Deschanel, ASC brings a unique perspective to this German film about an artist struggling with his work, the horrors of World War II and the chaos of post-war Germany.

Frame grabs courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics. Production photos courtesy of Caleb Deschanel, ASC.

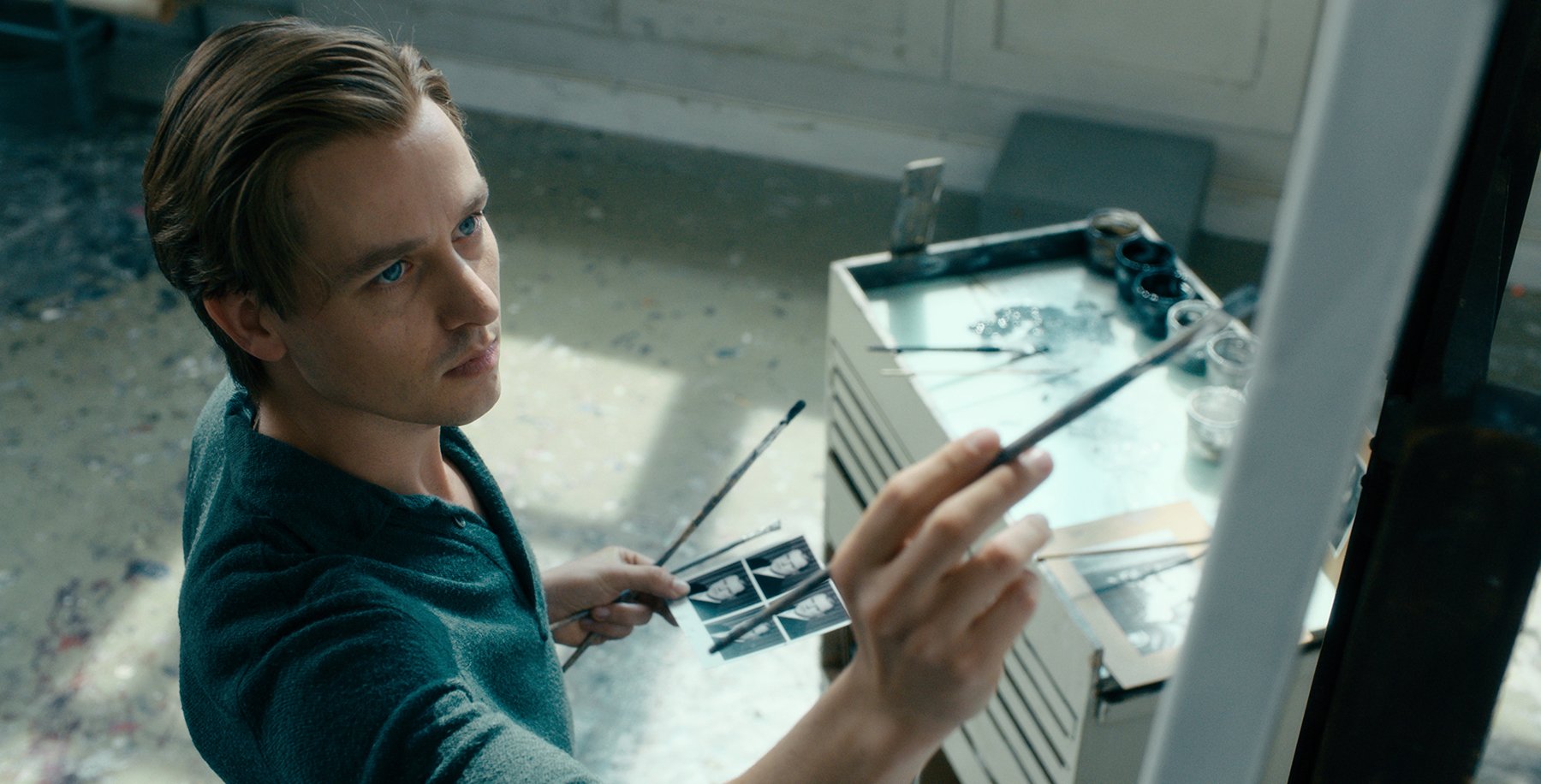

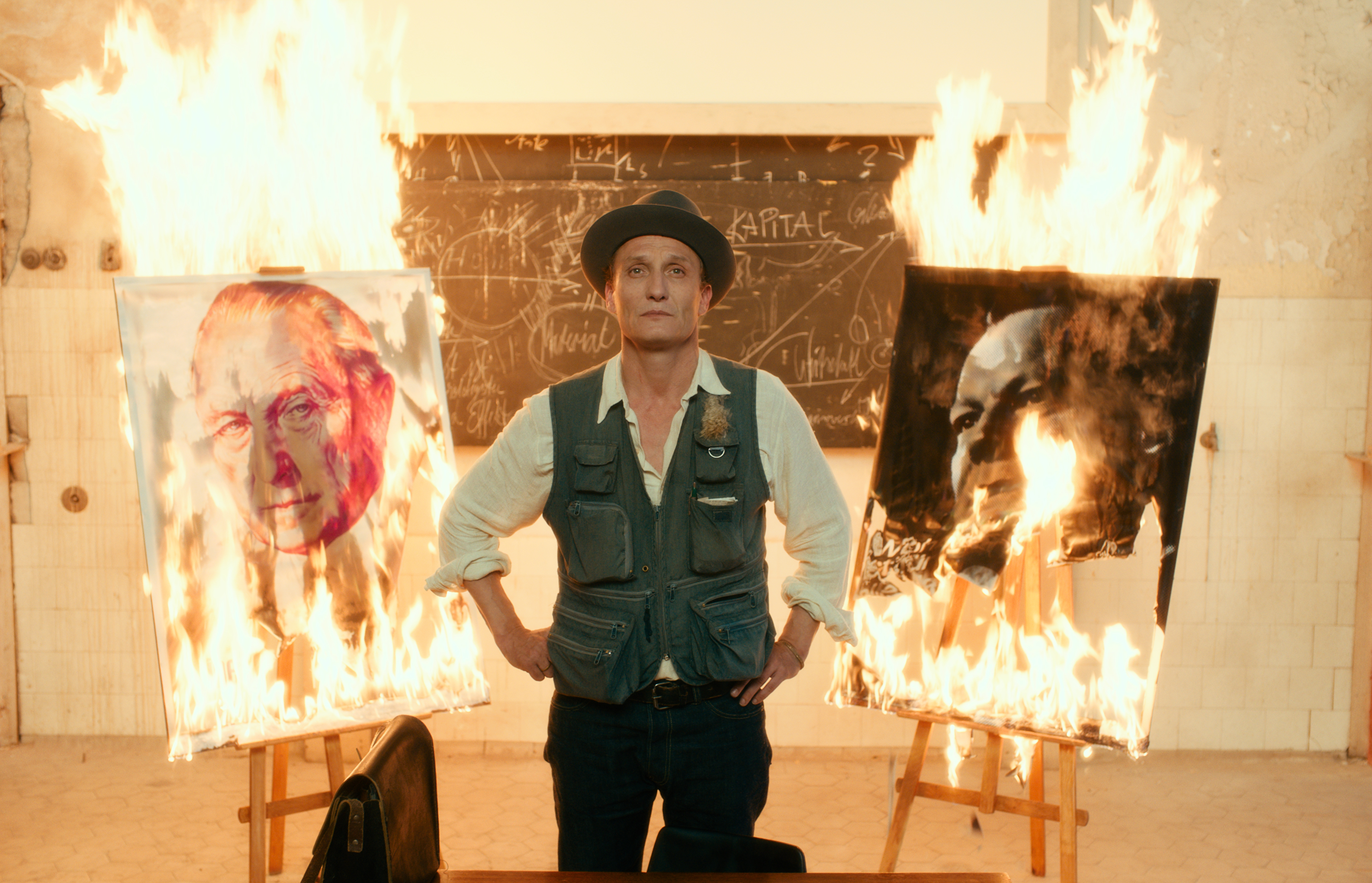

The German film Never Look Away (a.k.a. Werke ohne Autor) tells the story of an artist, Kurt Barnert (Tom Schilling), who comes of age during World War II and struggles to find his creative voice in the years that ensue. After falling in love with a fellow student, Ellie (Paula Beer), he must also come to terms with her disapproving father, Carl Seeband (Sebastian Koch), a prominent doctor determined to destroy their relationship. Based in large part on the tumultuous life of abstract artist Gerhard Richter, the story begins in 1937, when Barnert is 6 years old, and ends in 1962, when his work begins attracting notice.

Written and directed by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, Never Look Away marks the sixth Academy Award nomination for cinematographer Caleb Deschanel, ASC, who was the only American on the production’s creative team. The film has also been nominated for Best Foreign-Language Feature, an award Donnersmarck won in 2007 for The Lives of Others (AC March ’07).

After a brief qualifying run in Los Angeles late last year, Never Look Away has opened in New York and will reopen in L.A. Feb. 8, with other U.S. cities to follow. Deschanel recently connected with American Cinematographer from London to discuss his work on the picture.

“What I love about this film is that I think Florian really captures the mystery of artistic inspiration.”

American Cinematographer: Congratulations on your Oscar nomination. Were you surprised?

Caleb Deschanel, ASC: Thank you. It’s so exciting. I had zero expectations for a cinematography nomination, and although I was hoping the film would be nominated for Foreign-Language Film, I thought it was kind of a long shot because I had the impression not many people saw it — it’s a three-hour German movie that didn’t get a big awards campaign. But toward the end of the year, as it screened at the Academy, people kept calling me up and telling me how wonderful it was. I’m just happy people have discovered it.

Were you at all daunted by the prospect of shooting a movie in a foreign language?

Well, The Passion of the Christ [AC March ’04] was in Aramaic and Latin, but in that case, nobody on the set understood what was being said, whereas on this movie, I was the only one who had no idea what was going on [laughs]. First of all, it forced me to know the script really well. I had it virtually memorized, so when people were talking, I knew everything they were saying even though I didn’t understand the words. It makes you pay very close attention to actors’ expressions and body language; you really become aware when there’s a change in the rhythm of their speech, a pause, a slight change in their emotions. You go by all these minute gestures, which are how actors really express themselves. I would often surprise Florian by saying, ‘That was the best take,’ and he would say, ‘How did you know?’ It’s pretty remarkable that I was able to pick it up just by observing all those details. And it was fun because the actors were so great.

Are there films about art or artists that are especially meaningful for you?

Not really. I find that most of those movies tend to oversimplify what it was that inspired the artist. What I love about this film is that I think Florian really captures the mystery of artistic inspiration. When you’re any kind of artist, I think what you create is kind of a mystery to you. I always feel that I can be very proud of things I’ve created because it’s not tied to my ego; it’s something deep in my psyche and part of my subconscious that inspired whatever I did. I can be as surprised or moved by something I do as anybody because it comes from this mysterious place. I think Florian was able to capture that, to really come to an understanding of that spirit, and also to capture how difficult it sometimes is for an artist to know he wants to be an artist and struggle with all sorts of different styles and methodologies before finally finding what works for him. What is it that keeps you going? At what age do you give up and say, ‘I’m not going to be a great artist?’ Or does success even matter? Is it just the work that matters to you?

“What made the story great was the life Gerhard Richter has lived. The film is not a 100-percent-accurate account of his life, but, as incomprehensible and profound as it might be, a lot of what happens in the movie is true.”

Would the project have been as appealing to you if it weren’t so closely based on a real artist?

What made the story great was the life Gerhard Richter has lived. The film is not a 100-percent-accurate account of his life, but, as surprising and profound as it might be, a lot of what happens in the movie is true. The most outrageous things are true. When Florian called and asked me to meet with him to talk about the movie, we met at a restaurant in Santa Monica at 9 o’clock in the morning, he started telling me the story, and we were there till 1 o’clock in the afternoon. It was just so compelling I really, really wanted to do the movie. And I loved working with Florian; he’s absolutely brilliant.

How long was your prep?

Ten weeks, which was great, because the production was far-flung. We were based in Berlin, but we shot in many other locations in Germany, including Dresden, Düsseldorf, Potsdam and Görlitz, and in Poland very briefly. We shot mostly on location, so a lot of our prep was about finding the locations that would feel right for the story. After we wrapped, we had to go back and shoot in the winter because we needed some snow scenes. We shot those in Prague. It was a real mosaic that we had to piece together.

Did you take any of your key crew with you?

I didn’t take anybody. I used to do that in the old days, but most productions don’t want to pay for it anymore. I’ve also found that if there are good key people in a location and you can find them, they will have the best crews working for them. I was able to put together a terrific team on this film. My first assistant in L.A., Tommy Tieche, recommended a German assistant he’d worked with in Iceland, Rafi Jeneral, and Rafi was great. My gaffer, Florian Kronenberger, was pretty young, but I just had a good instinct about him; he had a great attitude and the best crew. [Key grip] Michael Müller was probably the most experienced on the crew, and he was excellent. Sebastian Meuschel had done some wonderful work and became my Steadicam and camera operator.

“I sort of go by instinct and emotions on these things, and this didn’t seem like a movie that wanted to be widescreen. It’s an intimate story.”

What were some of your technical considerations?

Somehow it felt more appropriate, more old-fashioned, to frame in 1.85, and Florian and I liked that aspect ratio for a lot of our locations, too. I sort of go by instinct and emotions on these things, and this didn’t seem like a movie that wanted to be widescreen. It’s an intimate story. We also shot a lot of single camera, more than I’m used to, because the eyelines and points of view were so critical. Florian and I originally wanted to shoot on film — again, it felt right for the story’s period. The producers were convinced we should go digital, so we shot comparison tests on film and with an [ARRI] Alexa. There are no more professional film labs in all of Germany; when we started prep, the nearest lab was in Vienna. After looking at the tests, Florian and I were still convinced we should shoot on film, and a couple of weeks later, we called the lab in Vienna to let them know we’d be sending more tests, and they said, ‘Don’t bother, we just went out of business.’ That sealed the deal, so we went with the Alexa. In the DI, I added grain, using more earlier in the story and progressing to finer grain as we went along.

“[In post] I sometimes find the emotion I experience watching a finished scene is slightly different from the emotion I was thinking about when I shot it.”

Did you work with a colorist to develop LUTs to use on set?

We had a few simple LUTs, and we were probably 75 percent of the way there by the time we got to the DI, but I’m not one who believes in timing the film as I go along, because how I finally orchestrate the look depends on how the film is put together. I don’t believe you can time each scene separately and then put the picture together and have it work. The DI gives you a lot of flexibility to move colors around and create a symphony that goes from one color to another — warm to cool, for instance — and I always like to see the film cut together before I make final decisions. Scenes get moved around in the edit all the time, and even if they didn’t, I sometimes find the emotion I experience watching a finished scene is slightly different from the emotion I was thinking about when I shot it. For the DI on this movie, we auditioned different colorists at ARRI Munich, and I really liked [senior colorist Florian] ‘Utsi’ Martin’s sensibility. I worked with him and his associate, [senior colorist] Bianca Rudolph, and they were a really fine team.

How would you describe your creative brief on this film?

Light was the most important thing — how to express the emotion at the core of a scene through the color of the light, the intensity of it, the way it played on something or someone. That was always our guide. What do we need to tell the story? Does the light need to be in the actor’s face? Does the actor need to be silhouetted? What is it about an actor that’s really important? Each one of the actors in this movie had his or her own wonderful technique, and I learned it after a while by observing them. And, like I said, the observation was intensified by not speaking the language [laughs].

Florian liked the actors to be able to do whole scenes, to get into the rhythm and keep going. We rarely did scenes in small pieces if they involved dialogue. My dolly grip, Hans Hellner, built a rickshaw dolly that we used for very long takes with the Steadicam. For instance, we used it in the scene where Kurt and Dr. Seeband are walking home after dinner and discussing Ellie’s health and possible pregnancy. It was a long scene uphill, and the rickshaw dolly really helped Sebastian Meuschel survive the very long takes. KFlo — that’s what we called Florian Kronenberger, my gaffer, because there were so many Florians on the set — rigged the street with huge cranes in both directions so when we turned around, we could turn off some lights and turn on others and start shooting right away. He also positioned dozens of lights at ground level so light would appear and disappear on the actors as they walked, giving some sense of life to the street.

The residential spaces in the film look quite small. Can you describe how you approached one of those?

Well, the country house we used for Kurt’s childhood home was so small I literally couldn’t stand up inside — the ceiling in the main room, where we see Elisabeth [Saskia Rosendahl] playing the piano, was maybe 5 feet 9 inches. But the trickiest location was Kurt and Ellie’s apartment in Düsseldorf. That set was on the top floor of a four-story location in Potsdam, and it was really tough to get equipment up and down. And we were there in the middle of summer, so it was hot as hell! There was a space outside the windows where we could hide lights, but if we wanted any distance to the lights, we needed a crane. Almost all the scenes in there are at night, so that made it easier, but because we were blacked out on some of the hottest days, it was quite uncomfortable — but then, emotionally, most of those scenes were uncomfortable. We used another floor in that building for Ellie’s room in her parents’ house, and we also used that location for the exterior of her parents’ house. We shot the other interiors in the Seeband home at a location in Görlitz, and we were always trying to find ways to hide lights because the house wasn’t that big. KFlo had these 2-by-3-foot lighting panels that were very thin and easy to hide, and we often used those for key or fill.

The bombing of Dresden is depicted almost impressionistically after Kurt sees the chaff falling from sky.

A lot of that had to do with budget, but it was also about Kurt’s point of view as a 12-year-old. All the moments expressed in that sequence, which includes the death of the little girl next door, his cousins’ death on the Russian front, and Elisabeth’s death in the gas chamber, are representative. In a somewhat similar vein, when Hitler comes to Dresden earlier in the movie, we just hold the shot on Elisabeth as the motorcade passes by. She waits to hand Hitler the bouquet, and then she receives the little Nazi flag in return. We never wanted to show Hitler, and we didn’t need to. The entire story of that scene is told in her face, and you get it.

Watching Kurt discover his true style after so many years of trying is almost cathartic. How did you approach that scene?

That scene is just wonderful. It’s amazingly complex, and yet the real core of it is Tom Schilling’s performance, which is all silent and beautifully done. You can see how incredibly inspired he is by the things he’s looking at. When I read the script, that jumped out at me as a terrifying scene to shoot. There’s so much detail in it, and we had to shoot it in such a way that everything would tie together. Florian had written several pages of description. Working with that, we made a shot list, and then we spent days getting all the details — Kurt finishing the painting, blurring the painting, using the projector to superimpose another image onto it, and so on. Balancing the light of the projector with the other light playing in the room was critical. When we finished that scene, I felt like we really had the movie. Florian insisted I take all the photographs we used to create those photorealistic paintings, and I shot them with my Leica film camera. It was fun to see so many of them converted into paintings.

Is there any chance we’ll see those in the next ASC Photo Gallery exhibition?

[Laughs] No, because a condition of getting the rights to reproduce artists’ work in a movie is that you’ll destroy them afterward. All those works you see in the film’s opening scene, when Elisabeth takes Kurt to the ‘Degenerate Art’ exhibit, were really beautiful reproductions of famous works, but they all had to be destroyed, too. It’s a shame because in some cases, the originals don’t even exist anymore.

TECHNICAL SPECS

1.85:1

Digital Capture

ARRI Alexa XT Plus, Mini

ARRI/Zeiss Master Primes, Fujinon Alura

You'll find in-depth coverage on all of this year's Academy Award-nominated films here.