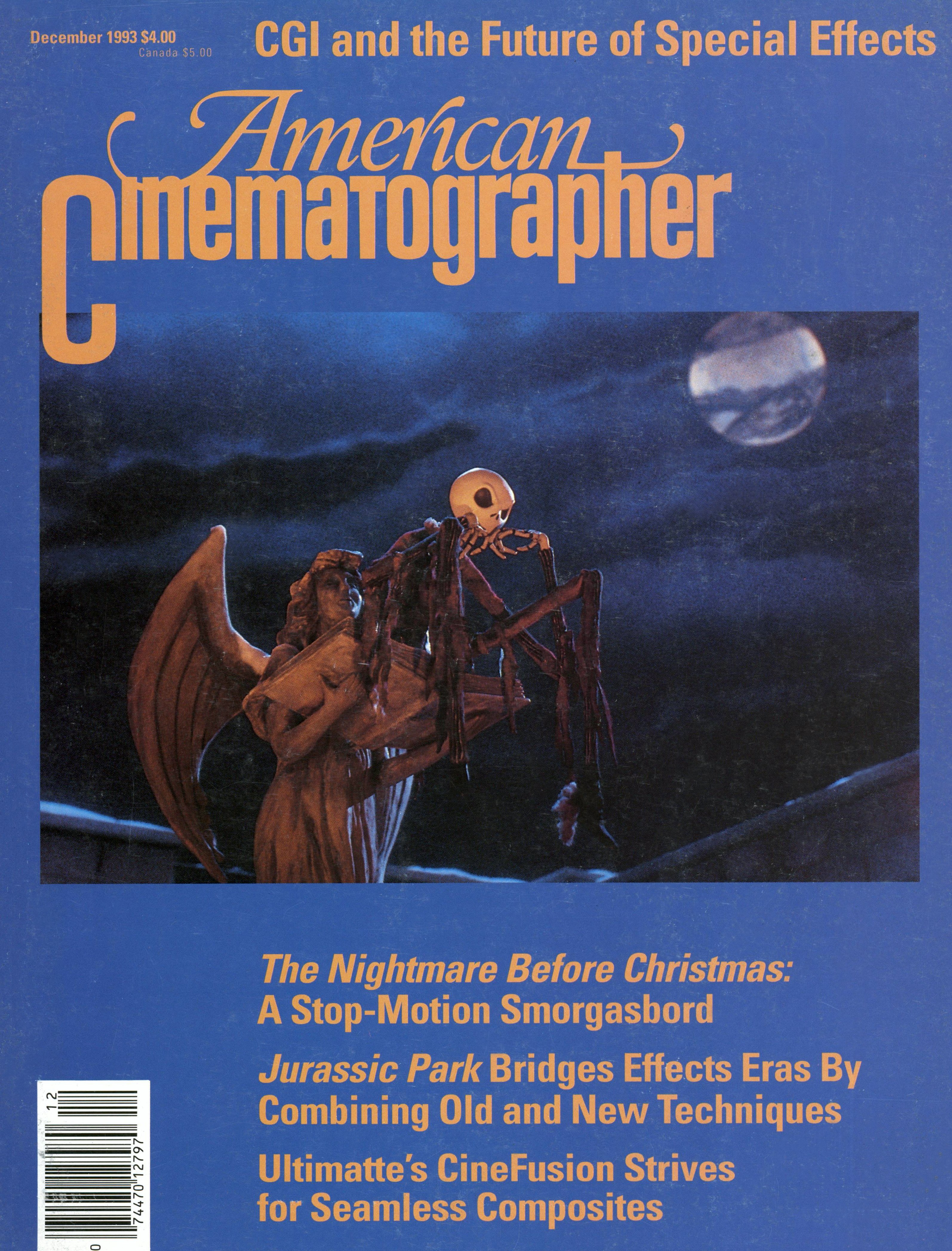

Stop Motion Without Compromise: The Nightmare Before Christmas

A report from the set of the "instant classic" that spent years germinating.

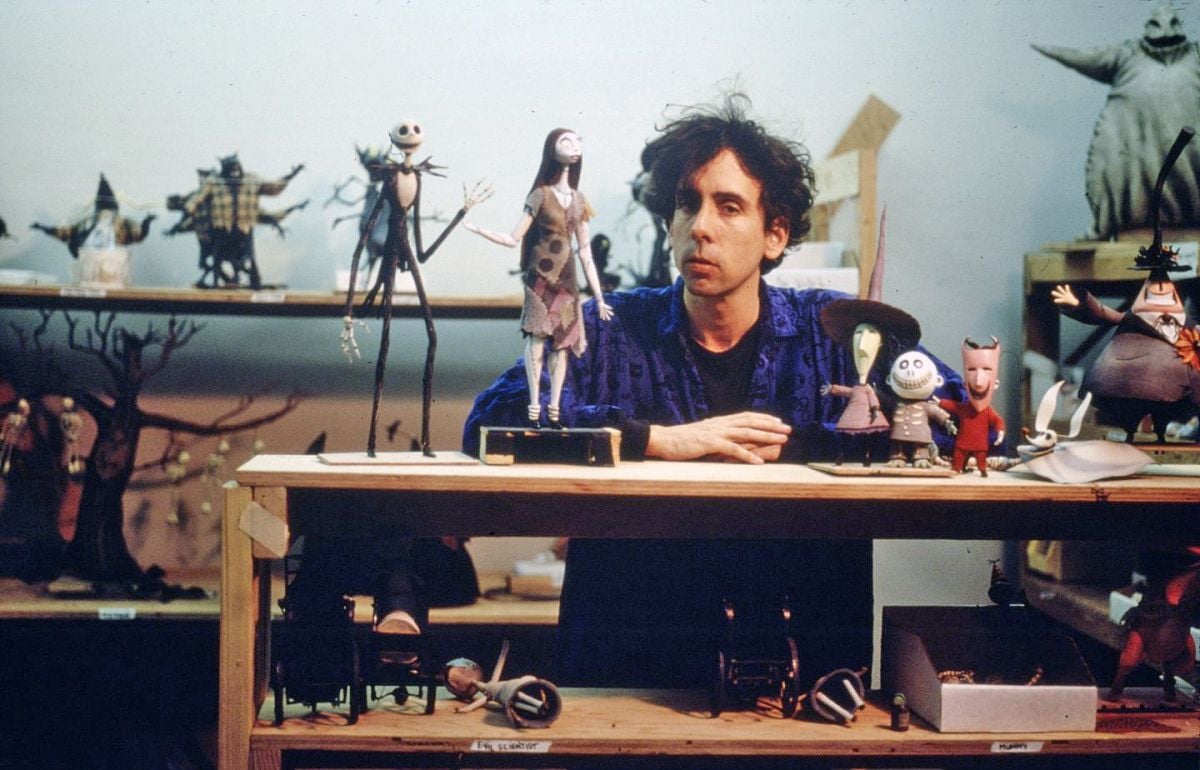

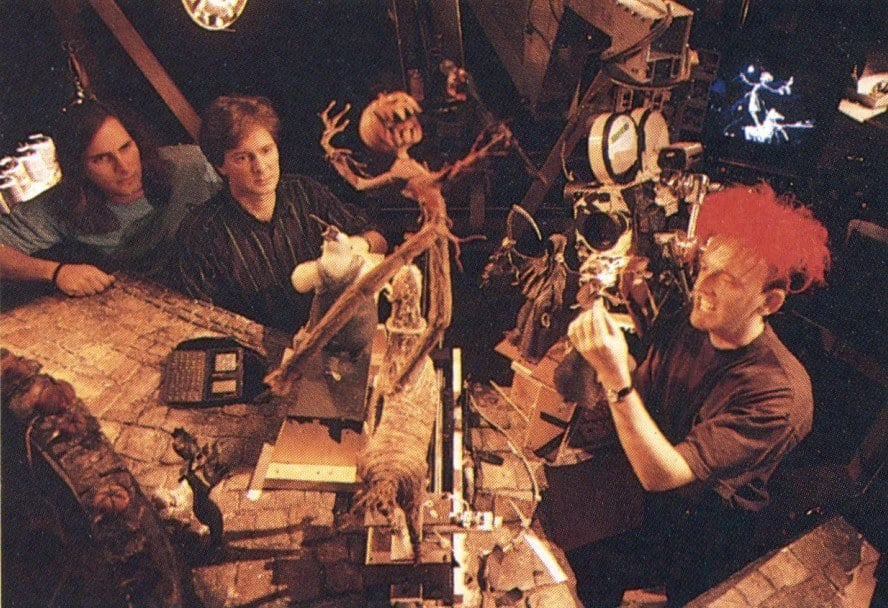

Editor’s Note: The Nightmare Before Christmas gives traditional stop-motion animation a shot in the arm. From its inception, director Henry Selick and his team set out to make sure that Nightmare would use many of the same techniques as live-action films. The result weaves elements of traditional frame-by-frame animation with the realism of actual three-dimensional sets built and lit as in live-action.

Selick introduced many innovations in his work for MTV and commercials and was anxious to try them on the big screen. He found a perfect partner in director of photography Pete Kozachik, a 14-year veteran animator/effects cinematographer and a lifelong devotee of stop motion (he remade King Kong in his garage at the age of 10).

What follows is Kozachik's detailed reminiscence of the thought processes and work methods that led to Nightmare.

Story Synopsis

Jack Skellington, king of Halloween, has grown tired of leading the happy ghouls of Halloween Town in their annual holiday preparations. Discovering another holiday on his accidental visit to Christmas Town, Jack is inspired to take over for Santa and delivers Christmas with a new spin on it. Jack learns a lesson from the resulting mayhem, and Santa gets the holiday back on track.

Cinematic Approach

"How will anybody be able to sit through 90 minutes of animated puppets?" I wondered. My first reaction to the proposed feature was that of a stop-motion fan turned apologist for too many examples of the craft that rely on novelty to support weak production values.

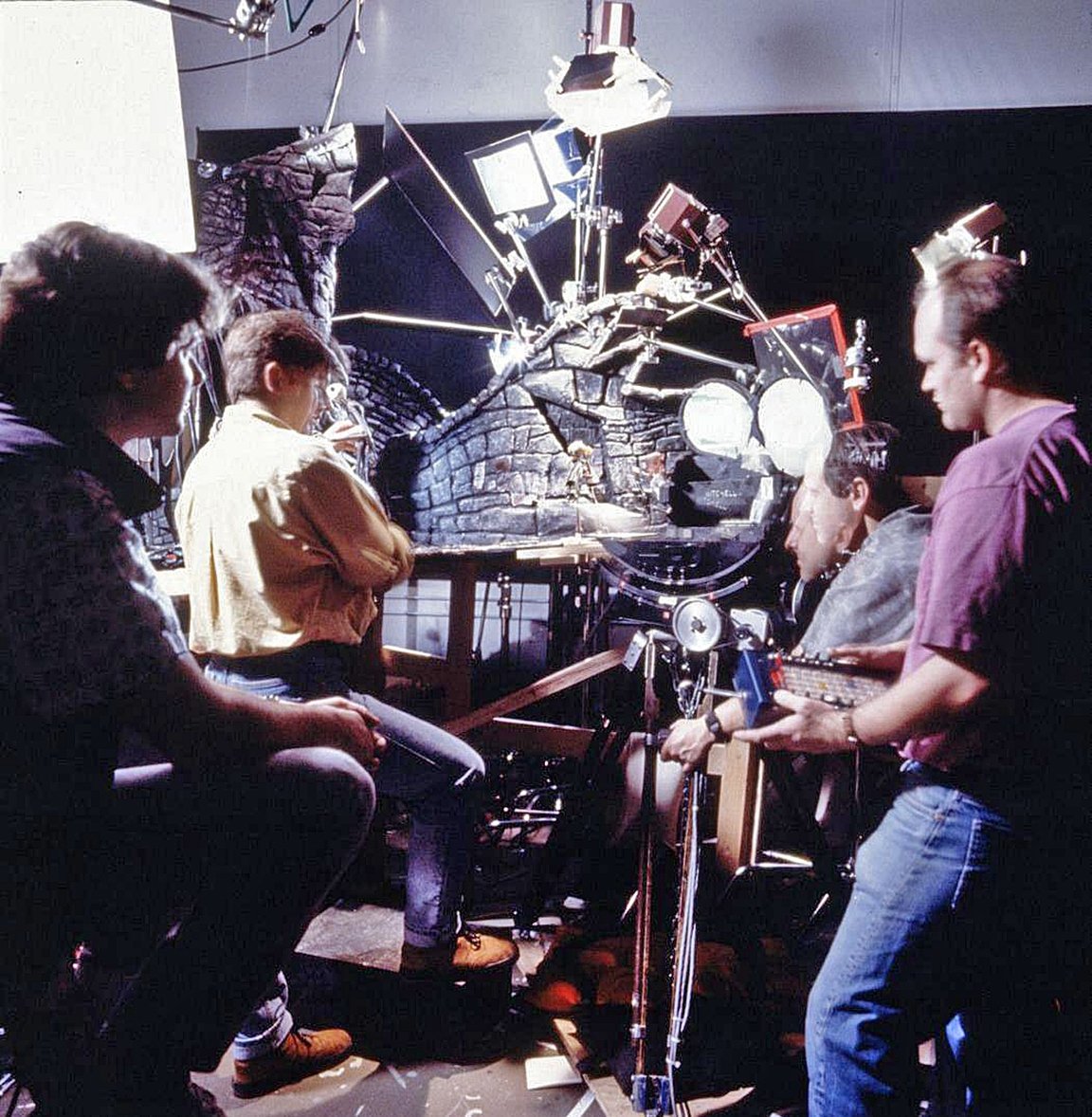

Director Henry Selick and I agreed that the expectations of a hip modern audience would be more sophisticated. To hold their interest, Nightmare would use the visual tools of live-action.

The camera crew would provide:

• Strong lighting design in support of mood and story

• Drama-enhancing camera angles and lens selection

• Unrestricted camera movement

• Atmospheric elements such as fog, snow, fire, and water

First, the lighting design needed a defining direction. Stop-motion films commonly use high-key soft lighting to showcase animation, often at the expense of drama. But the fantasy nature of Nightmare would benefit from a rich, expressionistic look.

Regarding Halloween as a “period holiday," I sought classic black-and-white thrillers for reference. The camera crew got together to view films and dissect example shots.

Although we were filming in color, black-and-white lighting techniques would prevail, with hard light, separation of planes by contrast, shadows as graphic elements, and theatrical pools for dramatic emphasis. Color would be used for its emotional content and avoided as a separating tool.

Art director Deane Taylor's Gothic Halloween sets invited such lighting with their strong angular forms and textures. Paint colors were held to a limited, grayed-down palette.

Contrast viewing glasses were copies of the dark yellow Mitchell viewfinder glass. Originally intended for black-and-white, the filter helped emphasize shape over color. Visual consultant Rick Heinrichs introduced selective contrast-enhancing with black and white paint.

Theatrical means were used to create the illusion of distance. One or more large scrims separated elements in long shots, slightly milking out blacks in the distance. When scrims could not be used, distant objects were given a cool gray over-spray instead.

Walking characters through obscuring shadows took some adjustment from lighting crews in the habit of displaying an animation as clearly as possible. The trick was to balance mood, lighting, and the readability of abstract characters. Narrow beamed specials helped, with the cooperation of animators hitting their marks.

Practical sources were important as story elements and mood enhancers. Deane designed candles, lanterns, bare electric globes, torches, a gas stove, and so forth as Halloween practicals. In the more cheerful Christmas Town, there were holiday lights, fireplaces, and table lamps. Set dresser Gretchen Scharfenberg developed an arsenal of dependable miniature lamps for the purpose. To avoid burnouts on multiple-day shots, Gretchen used high-reliability globes and ran them under voltage.

Some practicals could provide illumination themselves, but they usually needed help. In spooky scenes with a handheld lantern throwing a character's shadow, several bare inky globes were hidden and sequentially dimmed up and down in sync with the performance.

Day exteriors wouldn't be as atmospheric but needed to carry the seasonal feeling. Morning was keyed a signature pale yellow, and evening a limited range of rosy and purple. Key was from a low angle, as the sun is shining in October. Even in full daytime shots, the key direction was kept low and diffused with opal frost for softer shadows. Varying amounts of CT blue and a high fill level helped form the chilly overcast look of fall.

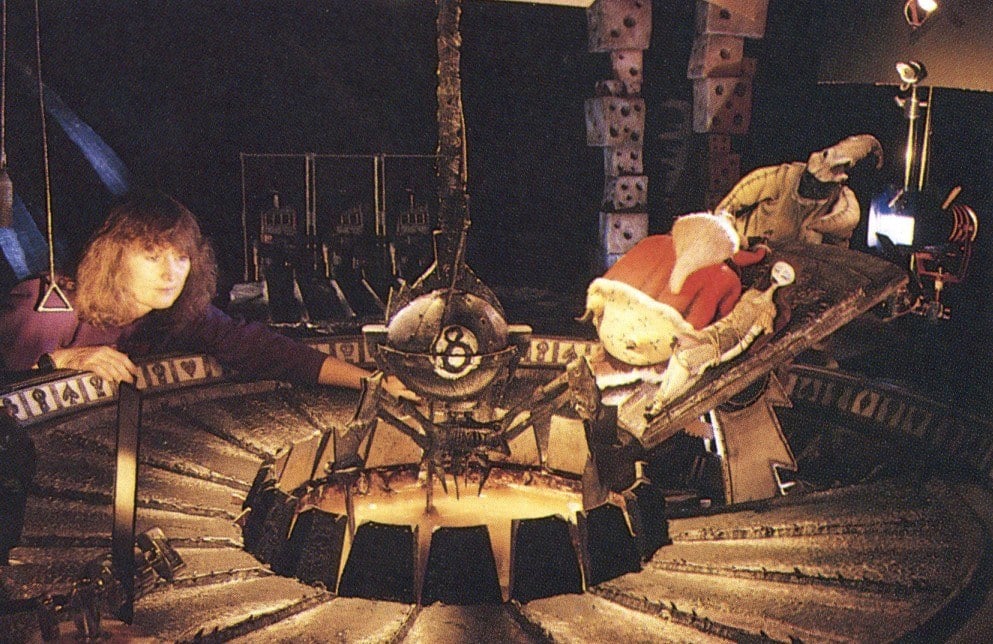

Three sequences needing different lighting for their own storytelling purposes, occur within the lair of bogeyman "Oogie Boogie." The "normal" lighting in this underground cavern was inspired by memories of scaring younger siblings with flashlights held under chins; the look was accomplished via variations of hard blue light with little or no fill.

Jack and Oogie's battle sequence was keyed from a central pit of hot glowing bug stew. Radially out from the pit light got dimmer, and was gelled down from yellow to orange to red, and finally underexposed purple. Rich Lehmann and Sara Mast enhanced the hot feel of the sequence by fogging areas of scenes with orange and yellow glows.

In a third lair sequence, we used only ultraviolet light and some animated practical chasers. Painted with fluorescent colors, selected set pieces and characters glowed like a '60s psychedelic poster. For the comfort of the animators, UV tubes were rigged to turn on for the exposure only.

Romantic interest is found in the character Sally, a shapely rag doll who wishes Jack would turn his narcissistic eyes her way. I had wanted to try glamour lighting in stop motion, and here was a chance. Would it translate, or just look silly? Photography of the leading ladies of the '40s was emulated with a high special on Sally's face, vignetting surrounding areas, and extra diffusion. Sometimes a tightly cut eyelight was included, requiring animators to keep Sally in the light, or animate dimmers. Ray Gilberti and Chris Peterson used this approach in a sentimental finale. Male crew members indicated a hormonal response in dailies, verifying the success of the experiment.

Jack's visits to Christmas Town and the Real World used lighting designs to set them apart from Halloween Town. Christmas Town exteriors were more softly lit, starting with a general cool blue key and fill. Henry desired a nighttime carnival feel in the town, which was accomplished by warmer colors from practical street lamps, windows, and strings of Christmas lights. Houses were accented with specials gelled the same colors as the buildings. These specials were allowed to creep onto the surrounding snow, giving the effect of houses radiating colors. The sky had a cheery blue horizon glow and pointed stars. Individual 30-watt star lights just behind the muslin sky backing were dressed to camera.

Christmas Town interiors were mostly lit with implied cheery fireplace light, or other warm practical sources.

The "real world" was supposed to look a bit askew, as if seen through the eyes of our otherworldly main character. Sets with distorted perspectives were used for interiors. We experimented with ripple effects, weird color timing, and the like, finding strong effects too distracting for a whole sequence. We settled on a theatrical filling-in of shadows with another color. This was done primarily by gelling fill lights. Eric Swenson and Mark Kohr also colored shadows by flashing the negative with a color before animation.

Freedom to light for stop motion in a no-compromise manner required some precautions. Mains voltage varied between 95 and 125 volts on some days. To avoid flicker, power was delivered to the stages from two industrial power conditioners, holding within one volt of 117 volts. This permitted shots to extend over several days without changing brightness.

Each of the 20 stages had 60 amps available. To accommodate power limits and keep the work environment cool, the whole show was bulbed down. 2K juniors used 1K globes, 1K babies used 500-watt globes, and so on. This was appreciated by animators who had worked under 10Ks before. Lower light levels were not a problem, since we could use long exposures in stop motion.

The most common light on the show was the 200-watt mini. This unit permitted control in selective lighting but had its own problems. FEV globes have shorter lives than most, standing a greater chance of burning out during a shot. Longer-life substitutes had an objectionable filament image compared to the flatter field of the FEV.

Under-driving FEVs at 100 volts greatly increased their life span, and a ¼ CTB gel brought them back to color temperature. Minis were held at 100 volts and were always dimmed up and down, never switched on full to avoid thermal shock. On multiple day shots, voltage readings were taken at shutdown, and reset the next day.

Bulbs would still go out during a shot. It is very easy to miss the event until too late, so current level sensing alarms were developed. These units, which beeped if one went out, were used on groups of five minis. A new stage protocol developed around the acceptable time limit within which alarms could remain on before other crews took matters into their own hands.

When a bulb went out, brightness was matched either from prior readings or comparative viewing on video frame storage devices used by the animators. Nightmare was shot on Eastman 5248 stock. To ensure rich blacks in the dark scenes, a set of printer lights was established that effectively rated the film at 64. Daytime scenes had a separate set of lights a half-stop brighter. During the two-year production, several new batches were bought. Some had a noticeable green/magenta shift, so new call lights were established for each batch. While reordering film during production is not ideal, it was recommended as being preferable to making one big order for the two-year schedule.

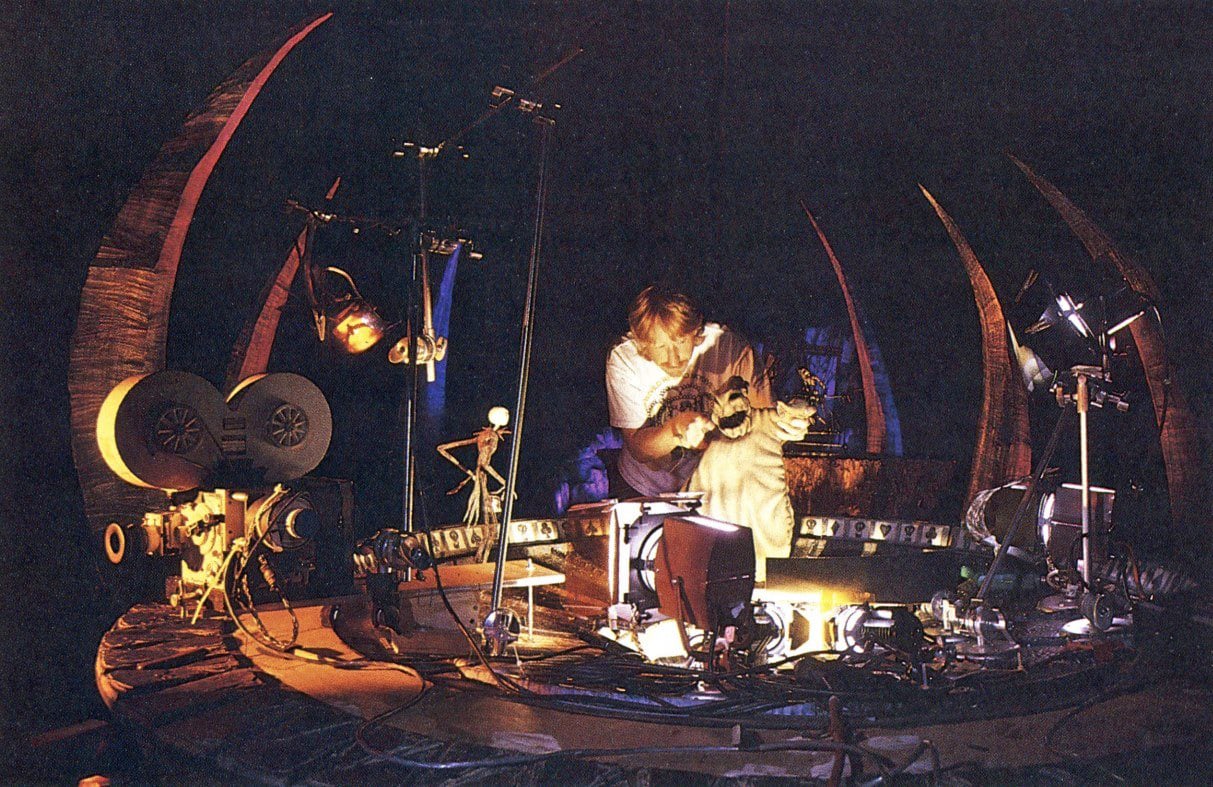

In stop-motion work, it's tempting to limit oneself to longer focal-length lenses to give the animator more workspace. Long lenses didn't always serve the story, and often we worked in the range of 17mm to 24mm, with the occasional use of a 15mm. My policy as an ex-animator was to try to give elbow room when possible, but not forsake dramatic impact when necessary. This required close cooperation between the camera crew and animator to assure sufficient access to the puppets.

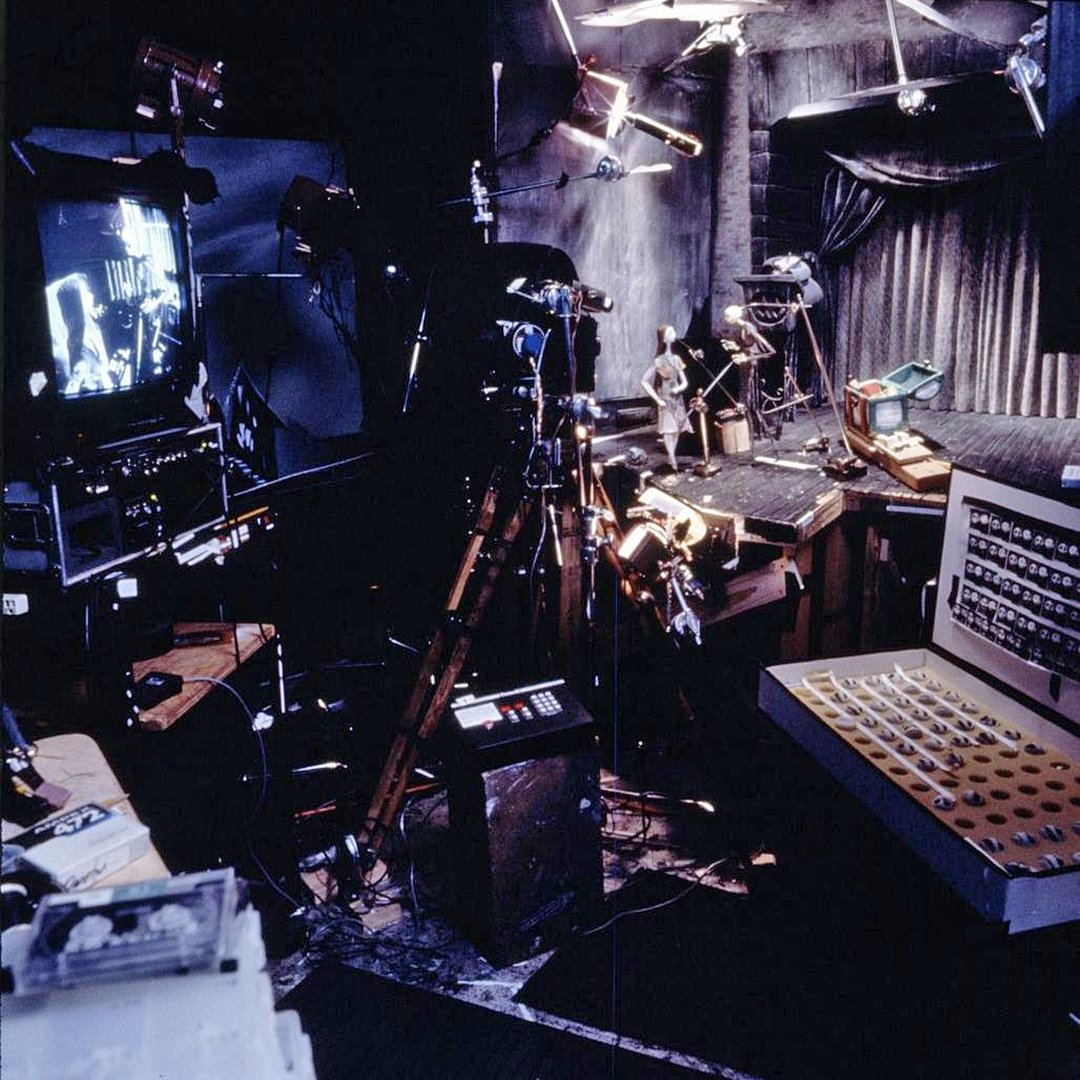

Our solutions included flying lights from overhead, mounting the camera on a Ubangi, shooting into a mirror, and cutting trap doors in the set. Video taps were used when the lens was very short, and the animator had to play directly to camera.

When all else failed, we used motion control to make the camera move out of the way between frames, and then reposition itself properly for each exposure. The choice of f-stop was based on several parameters. Depth of focus was used for separation, or to keep attention on a particular character, so wider stops were often used. This was different from most miniature work, where maximum depth is the goal. A balance was struck wherein drama was served, the animator had depth to perform in, and the shot didn't look toy-like. Limits due to available footcandles were eased by varying exposure time.

We shot day exteriors at smaller apertures than dark scenes in order to simulate conditions that would be encountered on a real location. With greater depth of focus, it was sometimes necessary to selectively blur competing background objects with Vaseline on the lens.

Henry and I wanted to use camera moves as freely as live-action does. The ability to follow action with pan and tilt would permit tighter framing and more dramatic angles. Dolly and boom movement would let us shift perspective during a shot, and push in or out for dramatic emphasis. And a flying camera would greatly enhance musical sequences, with its own performance complementing those of the characters.

At the beginning of the show I agreed to provide motion-control equipment, some pre-existing and the rest to be built for the production. This would include several motorized track and dolly units with motorized Worral heads, as well as four major flying camera rigs controlled by Tondreau and Kuper systems. As the show progressed, other crew members invested in their own rigs. Eventually, we had 14 motion-control setups operating concurrently.

One of my flying cameras was an experimental design resembling a large double-jointed desk lamp. Animation supervisor Eric Leighton named it "Luxo Senior" in homage to John Lasseter's film Luxo Jr. It could reach out over light stands and into a set with exceptional freedom. The extra joints provided a new challenge in programming motion. Operator Jo Carson tamed the Luxo in a sequence of shots that spirals in on Jack lying in a statue's arms, lamenting his ruination of Christmas.

The other flying cameras were more traditional swing and boom rigs and a truck/NS/EW rig, carrying pan/tilt heads. Each had their advantages and were employed for shots they could handle best. We built a number of devices to move characters and props as well as cameras. Operator Pat Sweeney used such a rig to impart an exciting performance to Jack's flying sleigh and skeleton reindeer. The gross motion of Zero flying was usually done with a compact rig that had X, Y, Z and rotation axes.

It was important to me that every camera crew be able to do moving camera shots. At least one member of each crew was a skilled motion-control operator. Close coordination between animator and camera operator was also crucial. Camera moves were preprogrammed based on exact frame counts and marks the animator was to hit. Filmed run-throughs were helpful in refining performances of puppet and camera, and identifying parts of the move that needed adjustment.

Most motion-control software can produce canned performances with smoothness and acceleration that belie their artificial source. I encouraged operators to design motion that looked more like the work of a live crew, varying speeds, leading or trailing characters, and searching at the end of a move. Did a move look like something a live dolly crew could do? If not, it was reworked.

Nightmare needed atmospheric effects throughout. Story points would require dense fog, boiling stew, fire in various forms, and many one-time effects. Mood-enhancing effects would be scattered throughout the film, too. Henry and I started with the ideal that we would add atmosphere as necessary, without thinking of it as a special effect. Opticals were considered a last resort for budgetary reasons, and because I preferred to stay with the original negative.

In-camera effects would be the standard. The simplest effects would be double-exposed into the animation, or laid in at the same time by shooting them through a half-silvered mirror. Live-action elements such as water splashes, flames, and billowing CO2 fog were pre-filmed, and low-contrast registered plates were made for subsequent rephotography.

In the time-honored tradition of Willis O'Brien and Ray Harryhausen, we shot the animation, wound back the film, and placed a white card into the darkened set where the live element plate was projected and re-photographed. There are several features I like about this process; it yields original negative quality, is relatively cheap, and permits finishing the shot in-house. Without much advance notice, we could decide, for example, to dress a few burning torches into a shot.

Other effects were produced on set and dx'd in without projection plates. Layers of mist were done by placing airbrushed art cards into the sets for subsequent passes. Sometimes the mist was given movement by using motion-controlled moire patterns and lots of diffusion.

When it was necessary for the animator to directly interact with some effect, a half-silvered mirror or "beam splitter" was used. The camera could see the puppets and the effect at the same time. A favorite example of this is operator Dave Hanks and animator Kim Blanchette's wolfman shaking snow off himself. Kim animated bits of cotton and paper snow on a velvet card which was at a right angle to the puppet. The beamsplitter in front of the camera combined puppet and snow.

Jack's faithful ghost-dog Zero had to appear transparent, and interact with Jack throughout the film. This was done by use of the beam splitter when interaction was to be very tight. It required setting up a limbo background for Zero to one side of the camera and beam splitting him in. A large diffusion filter was placed between Zero and the beam splitter for his wraith-like glow.

Some live-action effects were shot on the same negative as later animation. Pat Sweeney and Matt White dx'd live candle flames into a dark interior altar set. Jo Carson and Jim Matlosz shot boiling bug stew in Oogie's lair prior to animation. The stew was a bottom-lit pool of methocel, plastic bugs and dry ice.

Double-exposing effects into original negative poses two drawbacks. Errors in adding the effect can ruin days worth of animation. Checklists and precautions expanded as the shots got more complex.

The second drawback has to do with the non-repeatable nature of stop-motion puppets. In the example of a double-exposed background mist, the puppet may not cross in front of the mist, as it will be visible through the puppet. A labor-intensive and error-prone solution is to expose all separate elements onto a given frame before animating the puppet into its next pose. This means manually switching lights on and off, back winding frames, putting art cards in and out, and so forth, repeating the drill each frame. It has been done, but life is too short.

Before production began, I wrote some additional software for the Tondreau system to automate such processes. It has the form of a simple word processor, in which various motion-control functions are strung together into a script. For each frame the animator hits a shoot button, then a custom Rube Goldberg process is carried out by relays and stepping motors. The motion-control system can step through camera moves at the same time.

We used this new capability to produce a variety of in-camera effects, for example:

- Sel Eddy and Cameron Noble added glowing eyes, spotlight beams, and dissolves between normal and ultraviolet light in Oogie Boogie's lair

- Dave Hanks and Mike Bienstock dx'd moving wisps of fog between characters

- Eric Swenson and Carl Miller dx'd live-action flame plates onto torches held by puppets

- Pat Sweeney and Matt White racked focus and changed filters each frame to soften clouds between sharp stars and foreground action

- Jim Aupperle and Brian Van't Hul created rising fog by dissolving on-camera filters during animation

- Jo Carson and Jim Matlosz did tricky moving mirror shots in which the camera rig got out of the animator's way between exposures

- Eric Swenson created dazed Santa's double vision, with two counter-rotating pan and tilt moves dx'd during animation.

Some shots were traditional opticals done by Harry Walton, Michael Hinton, and Buena Vista Visual Effects. We used the Disney Computer-Aided Paint System (or CAPS) as a digital post facility. Headed by Ariel Shaw, CAPS fixed camera bumps during animation, obscured a negative scratch, and removed unwanted props left in shots. CAPS also helped accomplish some innovative composite work and added snow falling to several shots at the end of the film.

The high production values in Nightmare are the result of two years of effort by more than 100 dedicated production and craftspeople. The talented and hardworking camera crew made major contributions deserving praise and individual recognition. I thank them for their fine work and hope we may share another such adventure.

Kozachik earned accolades for his work in the film — including an Academy Award nomination for Best Visual Effects — which helped revive stop-motion animation as an art form. This led to his animated followup collaboration with Selick, the fantasy James and there Giant Peach (1996), featuring live-action cinematography by Hiro Narita, ASC.

Impressed by Kozachik's artistry, Narita — along with fellow ASC members Dennis Muren, Alex Funke and David Stump — recommended him for Society membership.

Kozachik's credits also include the stop-motion features Corpse Bride (2005; again in collaboration with Tim Burton) and Coraline (2009; directed by Selick).

He published his memoir in 2021: