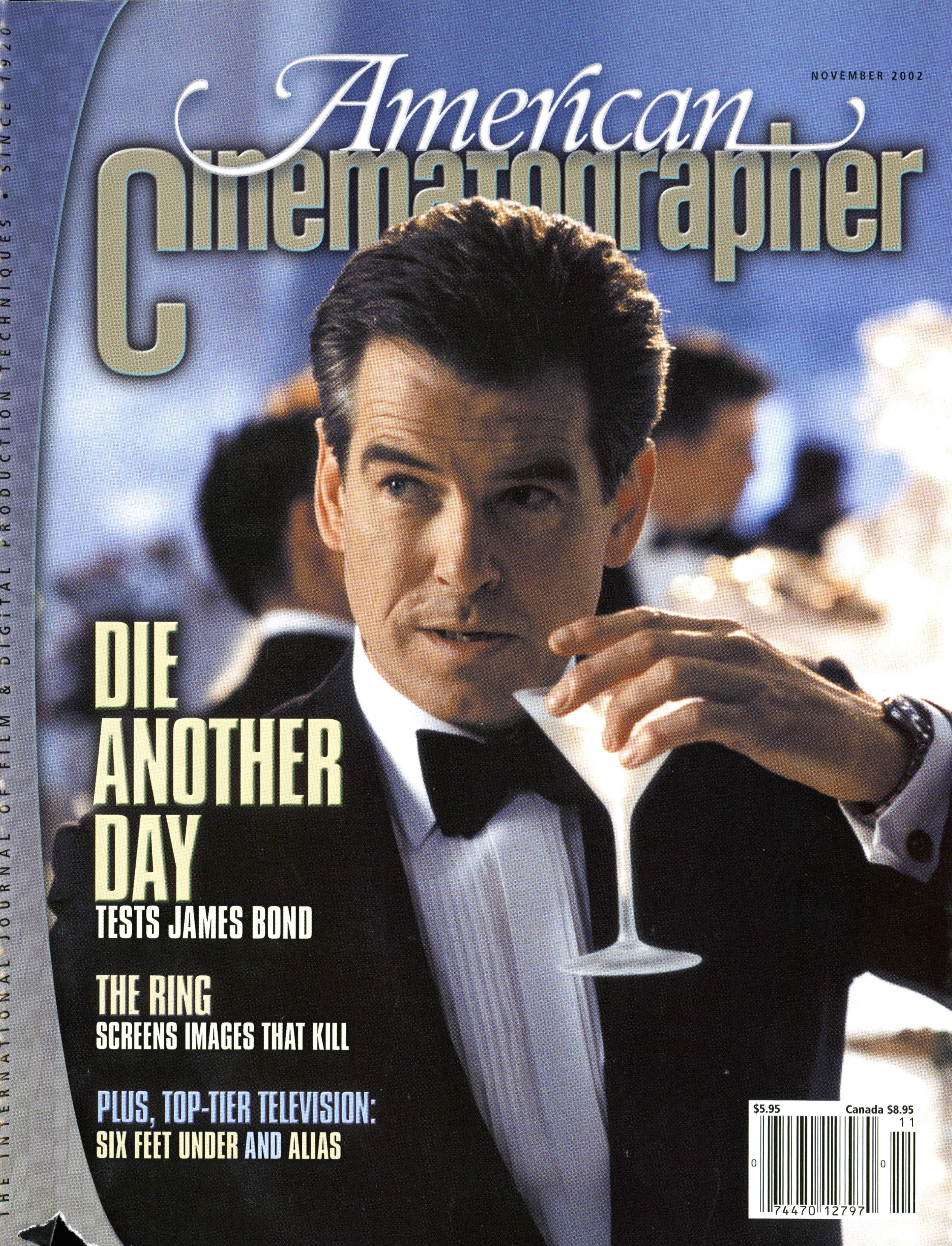

No Holds Barred: Die Another Day

An army of filmmakers, led by director Lee Tamahori and director of photography David Tattersall, BSC, brings James Bond’s 20th adventure to the screen.

Unit photography by Keith Hamshere, Photos courtesy of MGM. FlyingCam photo by Fred Martin, courtesy of FlyingCam.

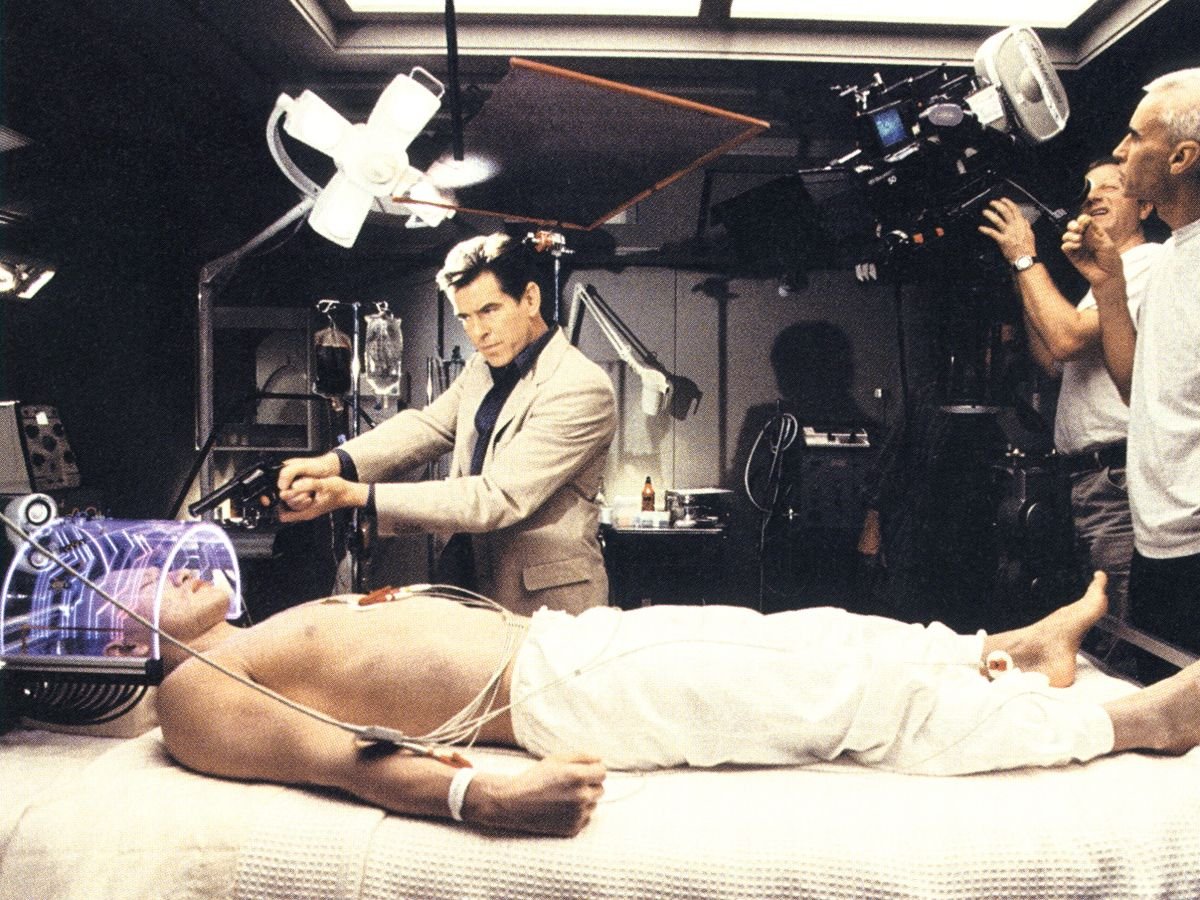

Director of photography David Tattersall, BSC isn’t always able to attend the premieres of his own pictures, but when Die Another Day, the 20th James Bond adventure, bows in London this month, he is likely to be there. In honor of the franchise’s 40th anniversary, Queen Elizabeth II will attend the film’s premiere at the Royal Albert Hall — and therefore, so will Tattersall. "It’s going to be the London movie event of the year," says the cinematographer, whose recent feature credits include Star Wars: Episode II (see AC Sept. ’01), The Majestic and Vertical Limit (AC Feb. ’01). "It’s unlikely I’ll get the day off, but I’ll try to slip away early."

Die Another Day takes Agent 007 (Pierce Brosnan) — along with Bond Girl du jour Jinx (Halle Berry) — on a hunt for a secret doomsday weapon called Icarus. The globetrotting thriller hops from North Korea to Hong Kong to Cuba to Iceland, but Tattersall concedes that plot and location had little to do with his attraction to the show. "It didn’t matter what the script was," he says. "Almost everyone in the movie business wants to work on a Bond movie, particularly English people. I’m the same."

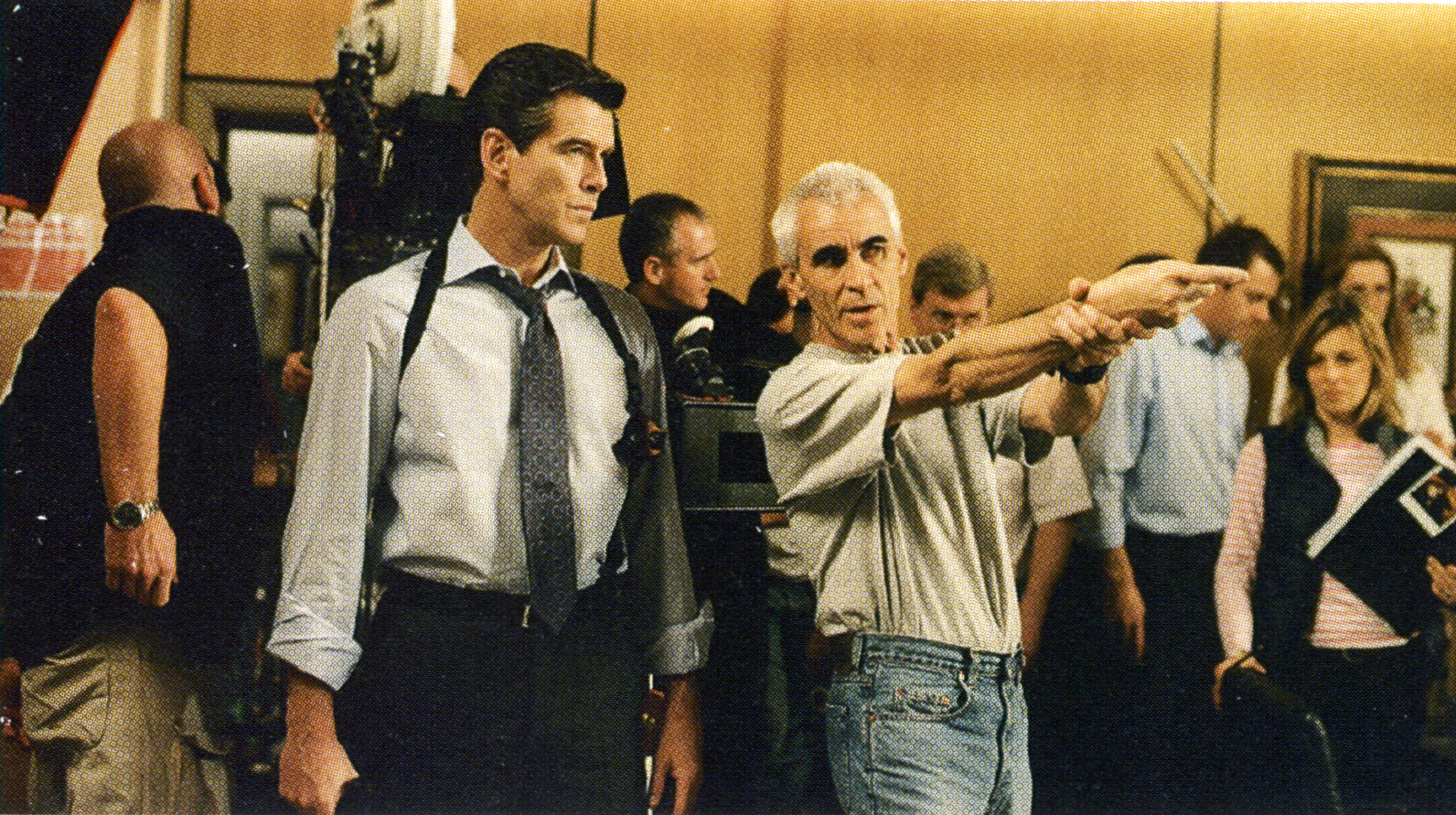

Director Lee Tamahori was another newcomer to the Bond series, and he maintains that it was the production’s international sheen that lured him across the Atlantic to Pinewood Studios, Bond’s production home since 1962’s Dr. No. As Tamahori and Tattersall were to discover, things are done a bit differently on a Bond film — especially the "location" work. "Even though they appear to have lots of exotic locales, the Bond movies are mostly shot on stages within the walls of Pinewood," Tattersall notes wryly.

Indeed, the thousand-man-strong Bond crew completely monopolized the English studio for nine months, with at least five separate units often shooting simultaneously on various stages. The action unit, led by director Vic Armstrong and cinematographer Jonathan Taylor, was in production almost as many days as Tattersall’s main unit, and it handled virtually all of Die Another Day’s location shooting. Everything else was recreated using miniatures or painted backdrops. Tamahori jokes, "David and I would run all over the world scouting these locations, only to end up faking them at Pinewood."

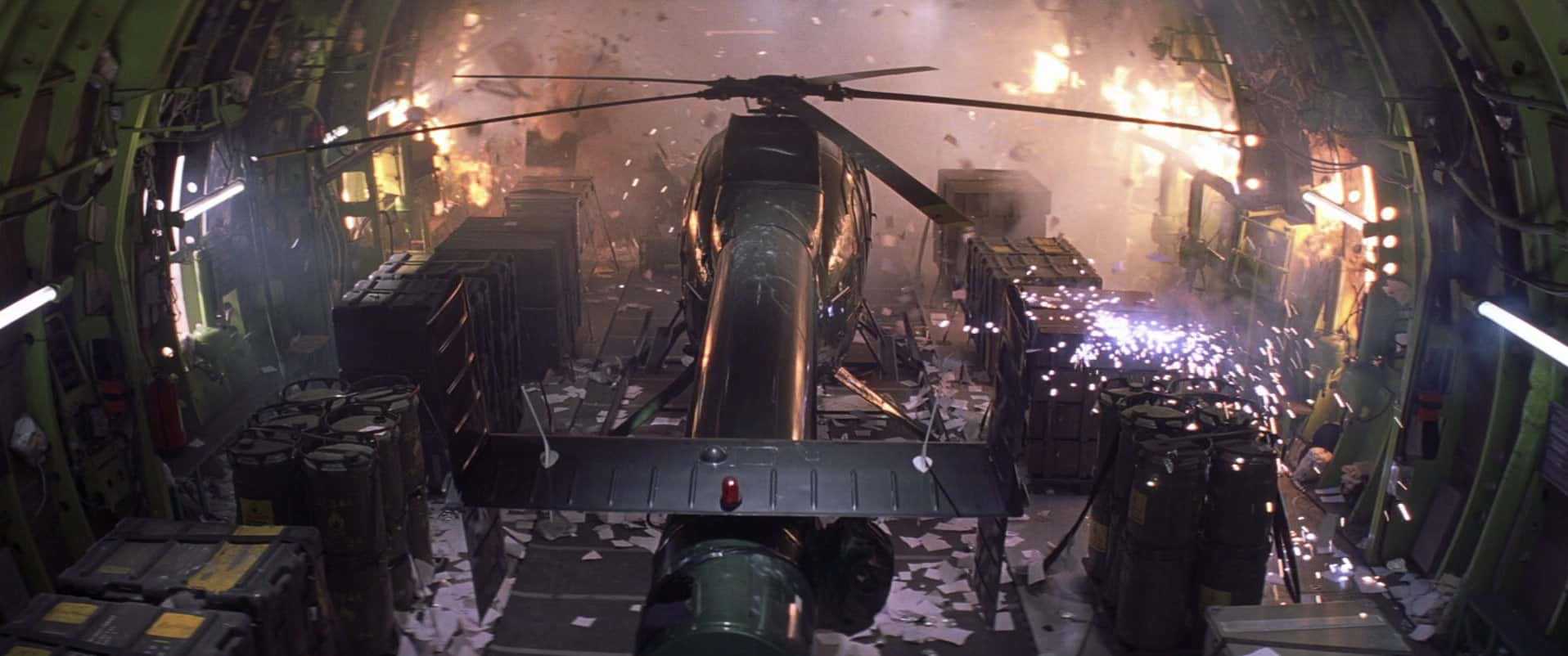

The numerous production units were another 007 idiosyncrasy to which Tattersall and Tamahori had to adapt. Tattersall attests that in terms of production time and logistics, the main unit was on almost equal footing with the units for action, insert, miniature, aerial, underwater and plate work. "It was just nuts," he remarks. "While we were on our stage, blowing up a Russian cargo plane with Pierce and Halle, the model unit was on another, blitzkrieging a 150' miniature of the North Korean DMZ; meanwhile, Vic was off with five or six cameras, flipping the Aston Martin over or ramming hovercrafts into each other."

Naturally, the multi-unit method created extra coordination concerns for the director and cinematographer. Asked how he supervised the filming of so many scenes at once — sometimes in different time zones — Tamahori concedes, “In a funny way, I didn’t. It’s not that you don’t direct the movie, obviously, but the Bond franchise is a well-oiled machine, and you work with a lot of people who’ve done this many times before.”

Extensive storyboard meetings between Tamahori, Tattersall and other key crew established a production blueprint, which each unit then followed with varying degrees of autonomy. “It really just involved a lot of trust — as well as the occasional reshoot,” Tattersall says. “The production was as tight as it could be. When Vic was in Iceland, our communication was fairly limited, but when his unit was on the stage next door, I’d run back and forth. The basic rule for stage interiors, which is probably standard on most multi-unit productions, was that the main unit would always start the sequence to establish the look, and then the other units would follow.”

Preproduction discussions also covered an issue all Bond filmmakers face: how to keep the “bulletproof genre” (as Tamahori describes it) contemporary while acknowledging decades of stylistic precedent. Tattersall decided that the best strategy would be to show off the series’ trappings — guns, gadgets and girls — rather than the filmmaking itself. "When you come aboard a Bond film, the initial urge is to push the envelope," he says. "There’s a cinematographic trend at the moment for desaturating color and adding grain, kind of dirtying up the image, but those sorts of treatments wouldn’t have been appropriate for Bond. We’re not talking cinéma vérité here — it’s full-on gloss, high-key and colorful."

Another 007 tradition is the anamorphic 2.40:1 format, which the filmmakers use to put an individual stamp on the picture’s mise en scène. The peculiarities of the format usually favor longer focal lengths and a correspondingly shallow depth of field. But Tamahori (who had been introduced to anamorphic by Don McAlpine, ASC, ACS on The Edge) insisted on wider angles for most of the coverage. "We’d do two-shots, even close-ups, on a 50mm," Tattersall says. "Some directors favor the 800mm end of a 3:1 zoom, but we rarely went above 135mm." Tamahori says he applies a "1.85 theology" to the widescreen format: "My pictures tend to have a certain degree of realism, and if you want that you have to get ‘in amongst things’ with wider lenses. The anamorphic format shouldn’t put you off."

Tattersall employed Panavision cameras and Primo lenses, calling on rental houses in both Hollywood and London to fill the huge production’s demand. "It’s a major project for the camera assistants to obtain this many anamorphic lenses and make sure they’re consistent," he notes. "All of these lenses are handmade, so they’re all slightly different. Fortunately, when we started gathering equipment, it was a quiet time on both sides of the Atlantic in terms of production, so we had the pick of the bunch. I bumped into [Panavision London assistant managing director] Hugh Whittaker in the studio car park one morning and said, ‘What are you doing here?’ And he said, ‘I figured you were shooting something interesting when I noticed you had 26 cameras booked out!’"

Tattersall employed straightforward means in creating the film’s look and distinguishing the various locales from one another. For scenes set in tropical Cuba, where Bond meets his cohort, Jinx, Tattersall shot through coral or straw filters to highlight the warm ambiance. When the plot moves on to Iceland, the cinematographer gelled his lamps with Rosco 65 Daylight Blue plus 34 CTB and filmed through an 82C filter. Of course, one of the most important concerns on any 007 film is photographing the Bond Girl with maximum glamour. While filming Berry, Tattersall used a 500-watt Obie Light, a portable, soft source that he mounted on the camera’s mattebox, and Tiffen Black Net diffusion filters on the lens. (For the record, he adds, "Halle didn’t need it.")

To help maintain visual continuity throughout the sprawling production, Tattersall decided to film the entire show on one stock, Kodak Vision 320T 5277. "It’s possible because the weather’s so lousy [in England]," he says. "You need a fast stock, even outside. I’ve grown to like it for studio interiors, so we used it for literally everything.

"We did several days of testing to establish optimal printer lights, and we had all the dailies printed at those lights with no graded prints," he continues. "They were generally pretty consistent. Of course, there were occasional fluctuations, but there was no doubt about where they’d come from, and adjustments could be made. If the printer lights are changing daily, it takes much longer to get to the bottom of any discrepancies — it could just be a low battery in my light meter, or it could be a voltage drop on the stage, or it could be a mistake setting the T-stop. Having one-light prints simplifies things enormously."

Die Another Day required six weeks of pre-rigging — and that was just for the first four sets. Much of that time was also devoted to the construction of a massive, hard source that would mimic the effect of the dreaded Icarus weapon. Arch-villain Gustav Graves (Toby Stephens) reveals his brainchild during a party outside his giant ice palace. The night exterior was filmed on Pinewood’s backlot and required a source that could illuminate an area "larger than Wembley Stadium," Tattersall says.

After searching for a satisfactory unit and coming up short, gaffer Eddie Knight suggested the production build its own. Tattersall agreed, and Knight set to work joining 1K Dinos into 40 pods of four lamps each. Then, with the special-effects crew’s help, he erected a frame and began bolting on the pods, testing each one and running it through a master dimmer. A dedicated, 200-kilowatt generator was brought in to power the cluster.

The rig was so large that it hung from its own corner of the soundstage during construction and so voracious that it could only be powered up in quarters. Knight and his team worked on it piecemeal while rigging the other sets, and it took about a week to complete. When Tattersall dimmed up the whole rig on the scene’s cue, 160,000 tungsten watts blasted over the backlot. When asked what the stop was, Knight says "It didn’t really matter — it was definitely way over the top!"

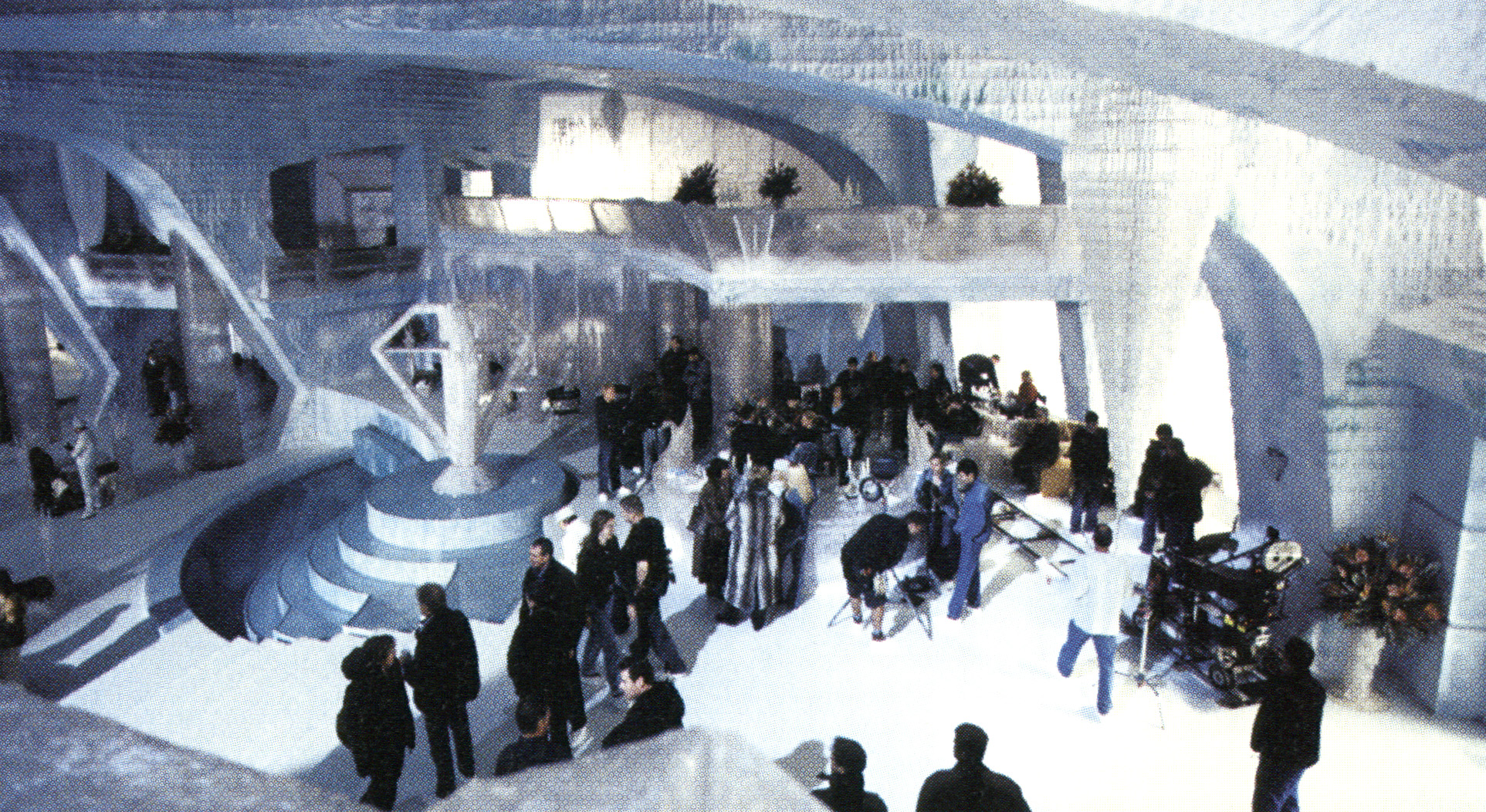

But the Icarus lamp was not the production’s most imposing lighting feat. That distinction belonged to the ice-palace set that was built on the 007 stage. Stretching three stories high and 250' long, the soundstage usually houses two or three large action sets, but for a sequence in which a Jaguar tails an Aston Martin up 360-degree ramps through curtains of melting ice water, the Bond crew needed all the space it could get.

Tattersall’s lighting scheme for the monstrous set had to be flexible and simple enough to hand over to Armstrong and Taylor’s action unit, which would spend a month creating the car chase. In designing it, Tattersall utilized an old-school previsualization method: "The art department made an 8' model of the set, and Eddie and I messed around with it with golfball bulbs and a little Dedo kit. We came up with a very simplified system."

Because the walls of the ice palace were made of translucent plastic, the cinematographer decided to light the whole set from the outside. "The simple — and expensive — solution was to put two complete rings [of lamps] all the way around the set. One ring pointed in and was gelled with 34 blue, and the other ring pointed out and bounced back and was gelled with Rosco 65. That way, if you were in any part of the set looking to an opposite wall, you’d probably only need one-half to two-thirds of the set lit. And by fading down the lamps behind the camera, you’d get your contrast. We had a ring of Mini- and Maxi-Brutes all sectioned into color-coded quadrants, so anyone on the ground could order the ones behind the camera faded down and the ones behind the actors faded up."

After several weeks of electrical rigging, Knight and his crew had cabled nearly two megawatts of power into the set. "It was a massive exercise," Tamahori recalls. "The lighting plan looked like the map of the London Underground." Both rings were hung from above to minimize safety concerns during the scene’s ice water downpour. The 5K and 10K lamps, all gelled with 3/4 CTB, were aimed at 40'x40' white muslin bounces hung behind the translucent walls. The resultant, double-diffused glow illuminated the set to a T4, virtually eliminated the need for fill, and ensured that the flooding water was always backlit. "There were open ceiling sections that also had 5Ks and 10Ks rigged around them, so we could backlight the water clean without going through the walls," Knight adds.

A location even larger than the ice palace set was The Eden Project, a biological conservatory in Cornwall that houses exotic plants inside geodesic domes, each about 500' long by 300' high. "That place is so big I’d need about 10 Icarus lamps to light it!" Knight says. "I told David I’d love to put some lamps in the air, but the dome was just too tall."

For a night scene in which Jinx rappels down from the ceiling of one of the domes, Tattersall and Knight placed uncorrected 18K HMIs on a service road to backlight the gigantic aluminum structure. The early hour contributed to the ambiance, according to Tattersall. "We were only allowed to shoot in the short time before the paying public was admitted," he recalls. "It was during the winter months, and we shot on tungsten film at the morning magic hour, which made it look like night." He also dotted the grounds with 1K and 2K Pars to backlight a blanket of mist created by the art department.

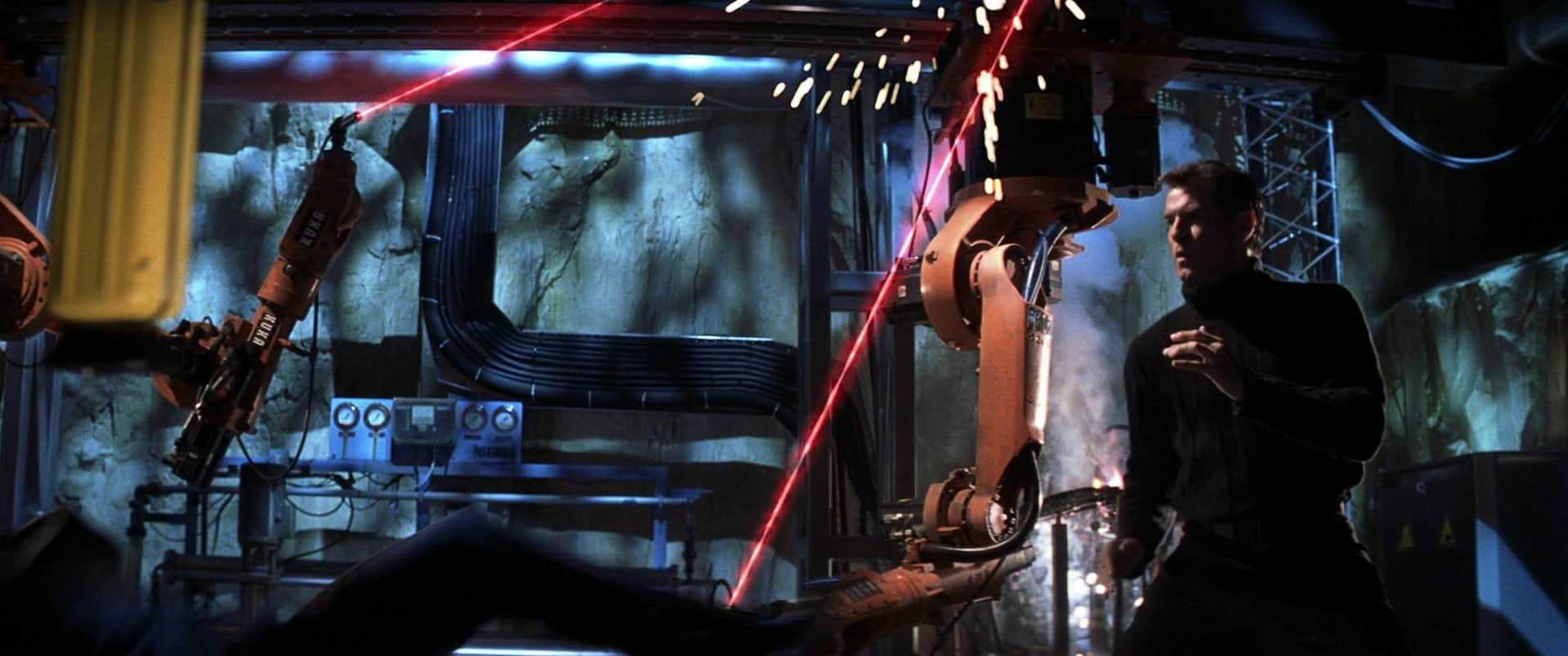

Much more manageable, yet no less notable was Tattersall’s lighting scheme for a hand-to-hand combat scene featuring Bond and Mr. Kill, a towering Maori thug. The fight takes place in a mechanical workroom filled with laser cutters running amok. Tattersall wanted the slashing ruby beams to stand out against another moving light pattern; he settled on the deep blue cast by theatrical units called Mac2000s. "They’re spotlights with two motorized gobos inside and an internal dichroic filter, so you can choose any color of the rainbow from one unit," he says. "We had 16 of them hanging from a ceiling grid and pointing straight down, all projecting a kinetic pattern over the whole set."

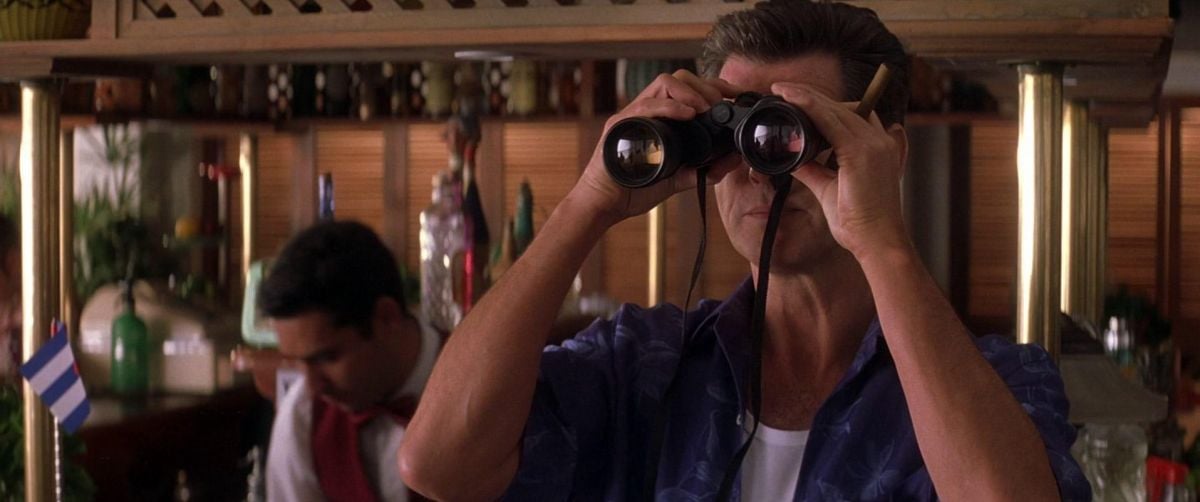

The main unit did manage to get out of the house for one scene, in which Bond meets Jinx at a Cuban beach bar. The crew traveled to Cadiz, Spain, which was doubling for Havana, but the expedition turned out to be, well, jinxed. "I think it was the worst weather Cadiz had on record — it was sideways rain," Tattersall says. "The one time we got away, we found ourselves desperate to get home!" The filmmakers were lucky enough to receive three hours of sunshine in which to film Berry’s angles, which faced toward the sea, in what Tattersall describes as "an homage to Dr. No." After that, however, nature’s disposition turned decidedly rude. "It was completely blowing a gale," the cinematographer says. "The beach bar had a rattan-bamboo roof just over the area where Jinx and Bond meet. We had to completely tent in the actors with tarpaulin like a mini-stage, and shoot over Halle to Pierce with the bar as the background."

The next morning, the crew discovered another calamity: a coastal squall the previous night had swept away Die Another Day’s entire beachfront façade. "We weren’t even able to do pickups," Tattersall says with a sigh. "One medium-wide angle is over Pierce to Halle, so that was that — no second-unit reshoots." (However, Tattersall was able to later increase color saturation and tweak contrast levels at London’s Computer Film Company, where the Cuba and North Korea sequences were taken to a digital intermediate.)

In the end, faking it — which is, after all, a spy’s finest skill — turned out to be the crew’s most reliable strategy. And what better showcase for cinematic subterfuge than a triptych of bravura chase-and-escape sequences? Die Another Day features a spectacular hovercraft race, Bond’s Aston Martin vs. a Jaguar driven by henchman Zao (Rick Yune) on a frozen Icelandic lake, and a helicopter soaring out of a Russian plane’s cargo bay in midair.

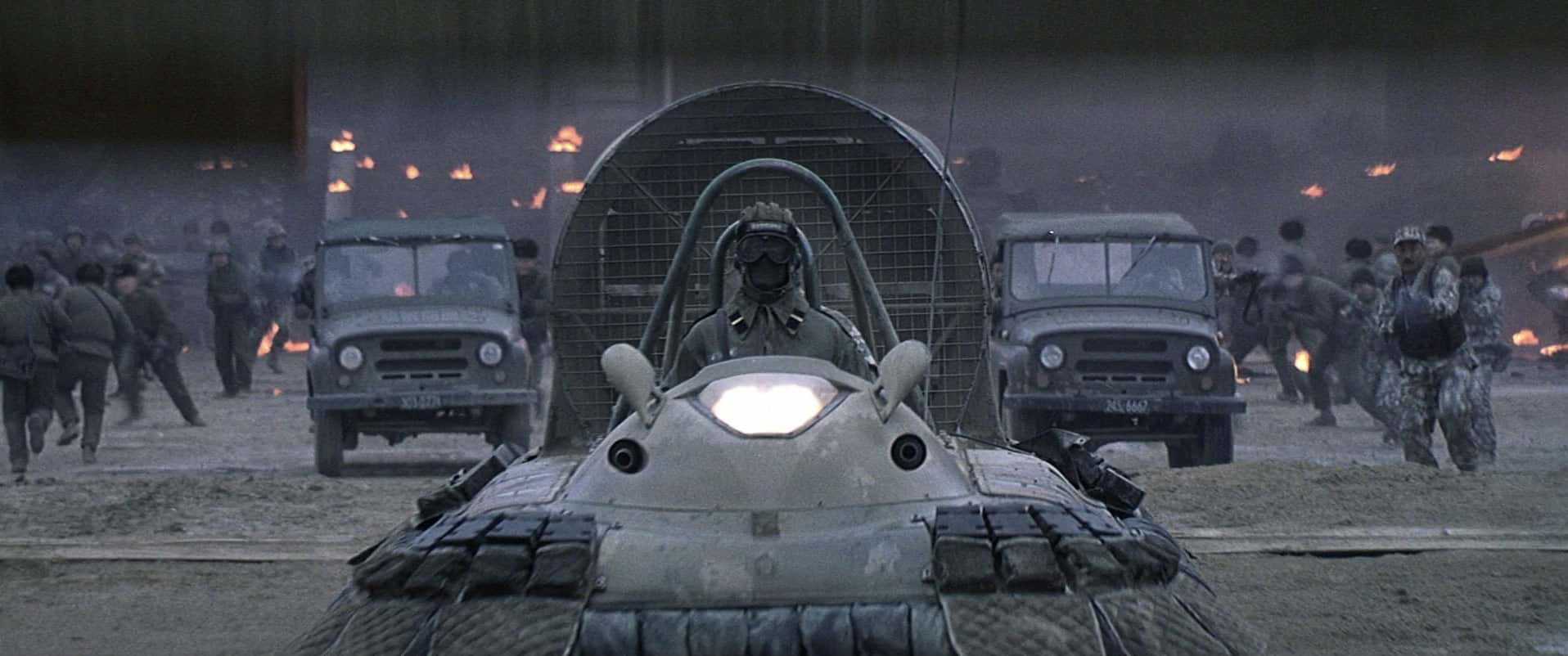

To coordinate 007’s extensive airborne gymnastics, the producers enlisted 25-year aerial-coordination veteran Mike Woodley. His advice led to significant adjustments of the script’s aircraft scenes, not least of which was the opening hovercraft chase. "They were looking for Caspian Sea Skimmers at first, which are cranoplanes that fly 50 feet above the water and take about four miles to turn," explains Woodley. "But hovercrafts can spin on their own axis, so I suggested that to Vic instead."

Armstrong approved, and he and Taylor took the action unit out to the Aldershot tank testing grounds near Pinewood to film the sequence. To prepare for inevitable crashes, Woodley procured two giant "mothercraft" vehicles, as well as four smaller hovercrafts, while Taylor mounted his camera on a Toyota ATV and undercranked it to cover the action. Midway into the ensuing demolition derby, however, it became clear that the hovercraft fleet would not be stout enough to complete the sequence without reinforcements. "They work fine on water and ice, but Vic’s guys found that they were very difficult to drive on land," Woodley says. "One of the stuntmen said to me, ‘I fly planes, I drive trains and I ride horses, so don’t worry about this.’ And 10 minutes later he came back and said, ‘I see what you mean.’" The production ultimately destroyed 18 hovercrafts; an in-house production line was initiated to keep up with the demand.

Taylor’s ATV created its own problems for the camera crew. "The hovercrafts were skimming over the terrain on a cushion of air, whereas we were on wheels, skidding and bouncing over a muddy tank field," Taylor says. He used C- and E-series anamorphic lenses, which are less bulky than their Primo counterparts, as well as a laser rangefinder to maintain focus. For critical frame stability, Taylor employed a newer camera mount called a Stab-C, which provides gyrostabilized control over three axes of motion. "It was pretty amazing, considering the amount of movement there was," he says of the mount. "We were able to do close-ups of Pierce driving the hovercraft with a 450mm lens and still keep our framing."

Just as integral to creating dynamic coverage of the scene was Emmanuel Previnaire’s FlyingCam system. The unit, which specializes in close-range aerial cinematography, houses a proprietary, gyro-stabilized Super 35mm camera on a miniature, radio-controlled helicopter. A FlyingCam fitted with a 200' magazine weighs just 30 pounds, and because it supports very wide lenses it can shoot as close as 10' from its subject.

Armstrong, who professes to "absolutely love this piece of equipment," had the FlyingCam capture high-speed coverage of the chase as well as aerial close-ups. Previnaire supervised the action while camera operator Phillipe Piron and pilot Bruno Ziegler executed Armstrong’s moves. One move involved swooping low between two hovercrafts as they zigzagged through a live minefield. "Vic rigged bombs in the ground that would pop up six feet in the air and then explode," Previnaire recalls. "We took the FlyingCam right through the smoke of the detonations with no problem." Piron and Ziegler, jogging behind the action to ensure a precise flight path, set their lens at hyperfocal distance to ensure maximum sharpness amid the chaos.

On a frozen lake near Hofn, Iceland, Taylor and Armstrong prepared the prelude to the ice-palace car chase. On hand were four Astons and four Jags (all converted to four-wheel drive), as well as a custom-built, lightweight ATV for the camera. Taylor recalls, "The ice was a good foot thick, but we had flotation devices rigged to the camera vehicle just to be safe – though I imagine it would’ve sunk like a stone if it had broken through, with us along with it!"

"The whole chase was finished in two weeks, as we were blessed with fantastic weather," Armstrong says. The crew used its standard package of four cameras shooting simultaneously. To ensure a sufficiently dangerous-looking duel, the cars’ tires were only partially fitted with winter safety studs. Taylor occasionally narrowed his shutters to 90 and 45 degrees to add crispness to the skidding vehicles, and he even mounted a camera near the rear wheel wells "because those studs actually looked pretty cool chewing through the ice."

The film’s climax occurs on a Russian cargo plane in which Bond and Jinx are stowaways. Woodley procured a Russian Antonov-124 cargo jet to use for practical shooting – though not without some 007-style complications. "Three or four days before we were due to film on the plane, the Russian Mafia seized it," he says. "I had to get another on short notice from Ukraine, and as they don’t like the Russians, they thought it was great fun: they sent one with the registration number UR007. I had a few sleepless nights and a lot of sweating, but that’s the sort of thing I do."

The intrepid aerial coordinator also recommended some logistical adjustments to way the scene had been scripted. "The original idea was to have the heroes escape through the nose of the plane on a rope, which was being dangled from the back of a transport helicopter," he explains. "The problem with that idea is that at 200 miles per hour, if you were to open a window and put your hand out, your arm would be broken straight off.

"We were already on the Russian plane, and I suggested that the escape heli come out the back," he continues. "Everyone thought that was impossible because the tail rotor would come off, so I thought we could move forward into the 21st century and have a totally different helicopter that doesn’t have a tail rotor."

The crew hired one of the state-of-the-art aircraft from McDonnell/Boeing and staged the scene in an oversized mockup of the Antonov cargo bay. Tattersall filmed the helicopter flying out of the stage, and the scene was later married to footage of the helicopter pulling out of a midair dive. The only thing left to create was the Antonov’s takeoff at Kent’s Manston freight airport.

Once again, the crew faced a rigging time crunch. The Antonov had to be towed onto the runway and readied for takeoff, while the runway itself required supplemental lighting. "We had to wait until the last plane had landed before we began," Knight says. "We had to rig 500 Par cans along the runway to simulate the lights. I had a gang of guys all ready to go with the lamps marked with tape on trucks, and when I said ‘Go,’ one gang put 250 on one side and another gang did the other side. By the time they got the plane hooked up to the tow vehicle and got the cameras on the runway, our guys were just about ready to light it up. David was very pleased with our military operation."

- Anamorphic 2.40:1

- Panavision Millennium, XL; PanArri 435

- Primo, C- and E-series lenses

- Kodak Vision 320T 5277

- Digital Intermediate (selective) by Computer Film Company

- Printed on Kodak Vision 2383