On Location With Ryan’s Daughter

American Cinematographer editor journeys to an isolated corner of Ireland to observe filming of this new David Lean production.

Dingle, County Kerry, Eire — My flight from Dublin to Shannon (30 minutes) somehow manages to be almost two-and-a half-hours late in arriving, but the driver of the car MGM has sent to “collect” me is still patiently waiting at the airport. He’s a darlin’ man named Mike (What else?) with a leprechaun smile and a broad Kerry brogue, and as we drive the 105 miles to the village of Dingle he gives me a cook's tour commentary of the points of interest along the way. There is the restored castle of Bunratty with its adjacent country pub (Durty Nellie’s), several lesser keeps and the towns of Limerick and Tralee. We skirt Killarney as we enter the Kerry Peninsula, and all the laments of all the Irish tenors I’ve ever heard come flooding back.

I’m on my way to this remote corner of Ireland at the invitation of my good friend Freddie Young, BSC and director David Lean, who have been kind enough to ask me to come and observe the location filming of Ryan’s Daughter. Reunited again after working together on Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago, the famous director-cinematographer team has been shooting on this location since February, with sometime in October as an estimated completion date. Before coming here, I have gone to some pains to find out as much as possible about Ryan’s Daughter, an intimate story of simple people, vastly different in scope and nature from their two previous epic collaborations.

David Lean’s 15th motion picture, Ryan's Daughter is a triangular love story about a 20-year-old Irish girl — going through what screenwriter Robert Bolt calls “the whole tragi-comic business of growing up, of adjusting your aspirations to reality without abandoning them altogether” — her diffident schoolteacher husband 20 years her elder, and a young British officer wounded on the Western Front who becomes her lover.

The setting is Ireland in 1916, with the epoch-making events of the Easter Rising and the Western Front unfolding beyond the horizon of the coastal village where the story takes place. It is the intrusion of these seemingly faraway events which irrevocably changes the lives of the film’s central characters. Though the story is intimate, the scope of the picture — being entirely filmed on the wild, rugged Atlantic coast of Ireland — is very large indeed.

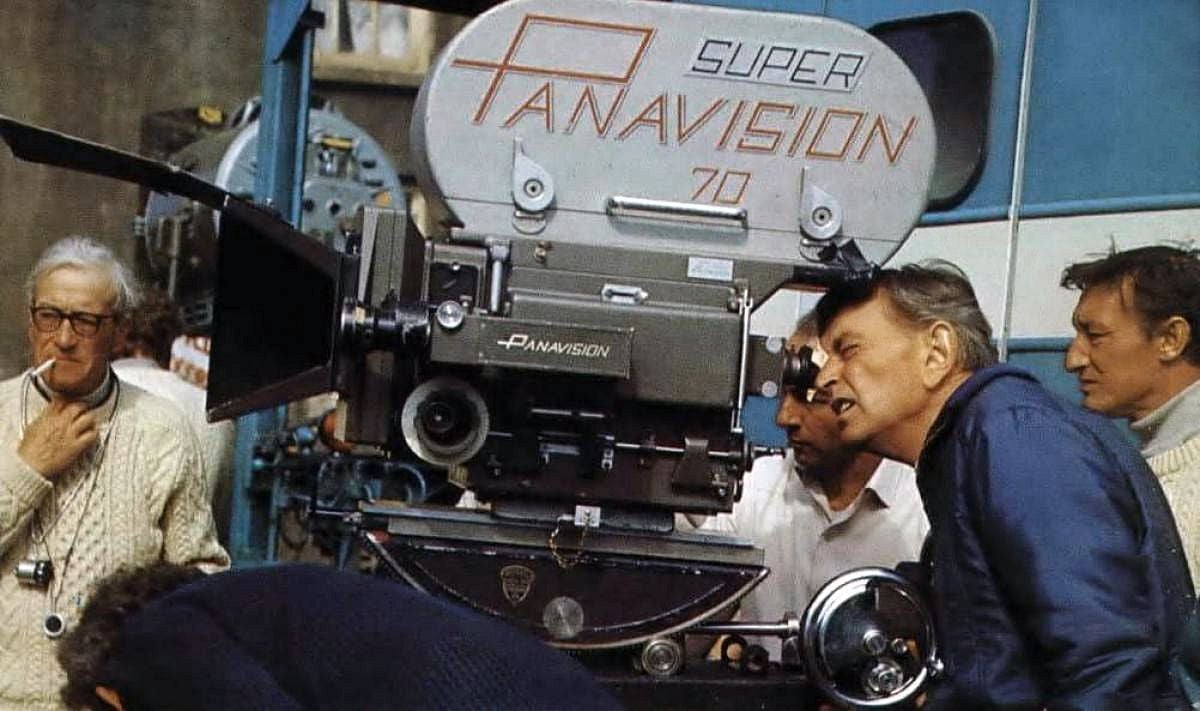

The film stars Robert Mitchum, Trevor Howard, Sarah Miles, Christopher Jones, John Mills and Leo McKern. A Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer release, it is being filmed in Super Panavision 70 and Metrocolor and produced by Anthony Havelock-Allan for Faraway Productions A. G.

While Bolt receives sole credit for the screenplay, he is the first to point out that it is as much Lean’s story as his. The two men spent 10 grueling months in perpetual story conference in Rome in 1967-’68 before they were satisfied that they had the story they had been seeking.

In October, 1968, after seeing every inch of Ireland’s rugged West Coast on foot, in a Land Rover, and by helicopter, Lean stood on a heather-clad hill at the tip of the Dingle Peninsula in County Kerry and made a momentous decision. There, with mountains on three sides and the Blasket Islands looming up to the west, he would build his fictional world of Kirrary.

The chosen site fulfilled all of the requirements of Bolt's screenplay: remoteness, a topography of mountains, bogs and barren moorland dropping dramatically to the granite cliff walls of the Atlantic, obvious poverty, and not a single sign that the area had progressed beyond 1916.

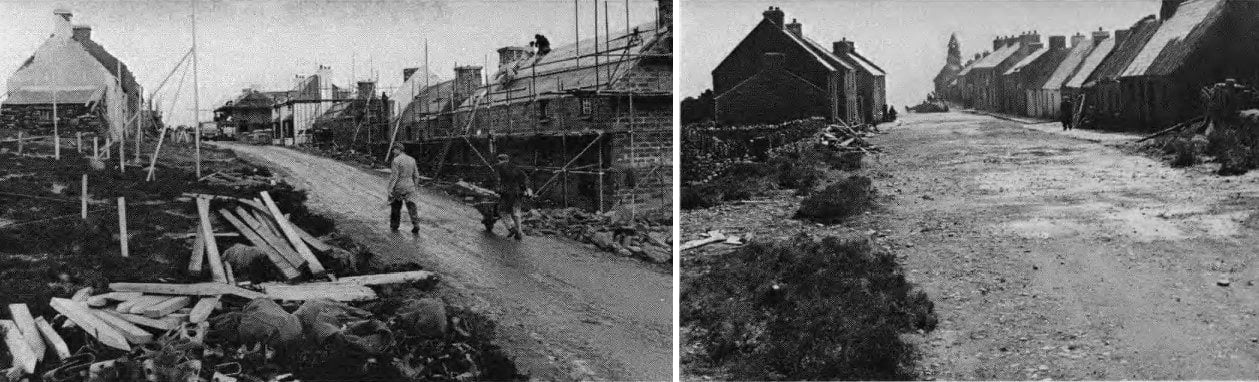

Lean also knew that he wanted much more than an exterior film set. Kirrary, he decided, would not be built of fiberboard and plaster, but of the same materials with which Kerrymen have been building their homes and outbuildings for centuries: stone, slate, tar, and thatching. It would stand as implacably in the Atlantic gales as any village in Ireland.

authentic full-scale structures of rough-hewn granite. Right: The completed village, with the

patina of centuries. Buildings, completely practical inside and out, include cottages, shops, a schoolhouse, church, post office and public house.

Less than three weeks after Lean chose his location, a crew of 200 Irish workers began the Herculean task of constructing no less than 40 full-scale structures, including houses, shops, a schoolhouse, a church, and a pub. Some 20,000 tons of rough-hewn granite and other indigenous stone were laboriously hauled over the hills along dirt tracks from a dozen different quarries.

In a matter of days, the hillside, where previously only scattered flocks of black-faced mountain sheep had relieved the endless vista of rock and heather, was swarming with giant earthmoving equipment, cement-mixers, and tractors and the skeletal outlines of scaffolding rose against the sky.

By the end of February 1969, Kirrary stood completed. At its miraculous birth, it acquired a title. It became the westernmost village in the European land mass, New York’s closest European neighbor, if you will. The Blasket Islands enjoyed this distinction until 1953, when the last inhabitants were forced by bad fishing seasons to re-settle on the mainland. The hamlet of Dunquin inherited the title and held it until David Lean built his Kirrary. It is in every manner a proper village, most of the houses having complete interiors, lights, and some plumbing. Filming of interior scenes is taking place in the houses themselves.

In addition to the village site itself. Lean found that County Kerry contained such variety of terrain that Ryan’s Daughter could be wholly filmed within its confines. He found sandy beaches stretching unbroken for miles at Inch and Banna Strand, sheltered coves at Dunquin and Ballyferriter, and the lovely lakes and woodlands around Killarney.

Lean’s headquarters for the entire production of Ryan’s Daughter, is the small market and port town of Dingle, located forty miles west of Killarney and ten miles east of the village location. In its eighteenth and nineteenth century halcyon days, Dingle was a relatively thriving port of call on the international sea lanes, with particularly strong trade ties to France and Spain. In fact, when the French Revolution broke out, Marie Antoinette considered coming to Dingle on the suggestion of an Irish officer in her personal guard. At the last moment, however, she elected to remain with her family and face inevitable execution.

Dingle is today distinguished by its 49 public houses, one for approximately every nine adults in the population of 1,400. Until it was abandoned in 1953, a picturesque narrow-gauge railway connected Dingle to Tralee, the county seat. The steam-powered train took two-and-a-half hours to cover the 32 miles across the Slieve Mish Mountains.

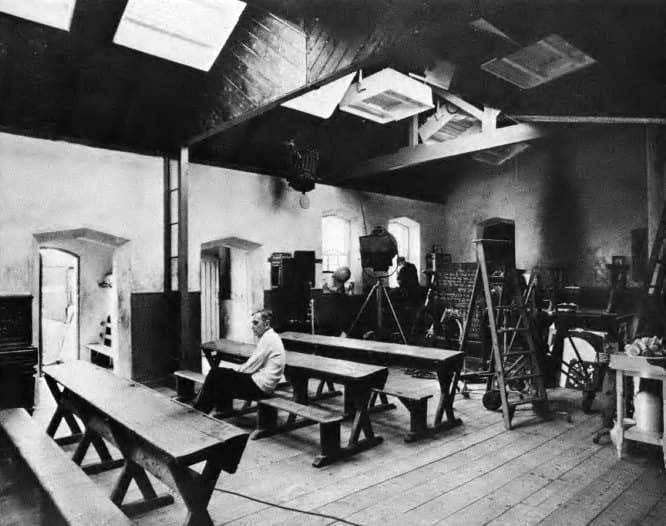

The old Dingle rail station is presently occupied by the film unit’s carpentry and plastering departments for set building. The production offices and actors’ dressing rooms are housed in a hotel on which work had been abandoned for lack of funds. Cutting rooms, prop department, special effects shop and other units offices are located in stores and guesthouses throughout the town’s narrow streets.

On the morning after my arrival at Dingle I am welcomed by MGM’s hardworking public relations representative, Bayley Silleck, who orders a car to take me out to the particular location where the company is scheduled to shoot that day.

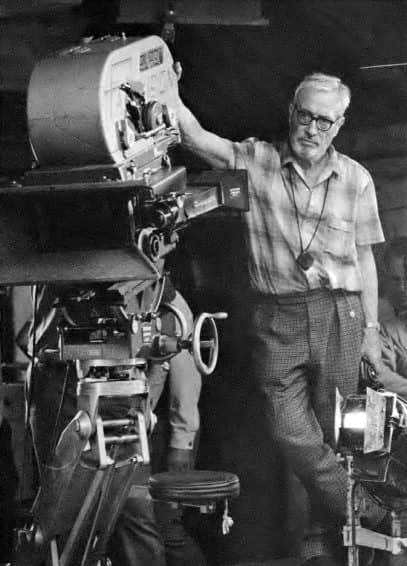

“We had quite a lot of problems filming Lawrence of Arabia and this is the same — except that we’re in Ireland this time.”

— Freddie Young, BSC

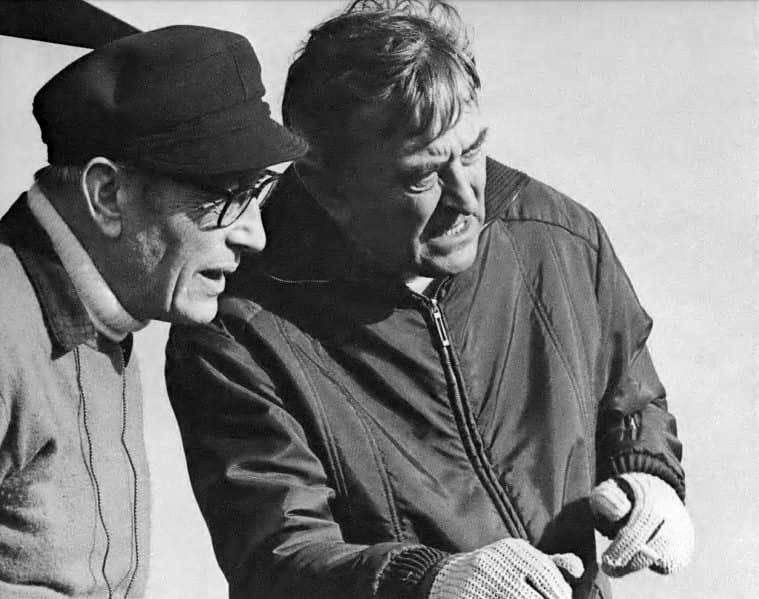

individual cinema craftsmen fused into a single creative entity. The unique rapport that exists

between them, plus technical skill of the highest order, has resulted in such film masterpieces as Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago, and now, Ryan's Daughter.

They are setting up inside of the village schoolhouse where (according to the script) Robert Mitchum, playing a shy, gentle schoolmaster, lives as well as teaches. There is a warm reunion on the set with Freddie Young, whom I haven’t seen since I visited his Battle of Britan set at Pinewood Studios last October. David Lean (the “Directors’ Director”) extends a cordial greeting, also — making me feel right at home. Good-natured Bob Mitchum, obviously happy to have another American on the set, begins to tell me humorous true stories about Hollywood personalities whom we both know — imitating their mannerisms and speech patterns to a tee. He’s got to be one of the funniest men alive.

I ask Freddie how the shooting is going and whether he's had to grapple with any special photographic problems.

“Well, Herb, there’s hundreds of problems,” he says, quite cheerfully, “but you’ve got to expect them when you’re doing a picture entirely on location. We had quite a lot of problems filming Lawrence of Arabia and this is the same — except that we’re in Ireland this time. We’ve built this entire village, which you’ve seen, that includes the schoolhouse, a grocery shop, cottages, a church, a police station, and a public house. All of these sets are completely practical inside, as well as outside, so that on bad days we’ve been able to use these interiors as cover sets. However, we’ve had so much rain and bad weather since we started shooting that before long we’ll have finished all of our interiors — and we’ve still got a lot of scenes to shoot that will require sunshine. We thought we were entitled to expect good weather during the summer, but it just hasn’t materialized."

I ask him if there is any chance that they will shoot background scenes in good weather and then use these as plates for either rear or front projection in the studio, and he replies: “No. We used to do that in the past, but on this picture everything’s got to be real. There’s no question that when, in the end, you get it, the result is much better. It doesn’t have that studio smell about it. Everything is authentic.”

soft-lights rigged to provide general illumination. Some of them are equipped with blue filters for daylight balance.

I notice that Freddie has the schoolhouse interior rigged for an incandescent balance, with sheets of plexiglass 85 daylight conversion material (plus neutral densities) snugly fitted over the windows. Spaced along the ceiling are large soft-light units to provide general fill, and I notice that some of those not now in use are covered with blue filters, in case he has to switch to a daylight balance. “We have to do that when a character opens the door to enter or leave, because there’s no good way to rig the doorways for daylight conversion,” he explains.

I get a graphic demonstration of the horrendous matching problems they've been having when, later, they are shooting inside the pub. This set has large windows opening onto the village street. When they start the sequence there is a pea-soup mist outside that blocks out all detail. Then the weather clears suddenly and there is blazing sunlight outside. Freddie breaks out the 6N and 9N neutral densities to combine with the 85s. In another hour the skies go leaden, the wind begins to howl and rain beats down on the roof. While Freddie copes with the exterior balance, the soundman supervises covering the roof with felt and rubber mats to deaden the pounding of the rain. Better they should be filming Wuthering Heights!

When shooting is completed on my first day in Dingle, Freddie Young invites me home to dinner at the “chalet” in nearby Ballydavid where he is staying with his charming wife, Joan (who used to be an assistant film editor in her single days), and their three-year-old son, David.

Freddie's handsome beard was not grown for

cosmetic purposes, but to protect his hide

from the raw Irish winds.

After dinner, naturally, we talk shop and I remark that it must have been difficult to estimate in advance the amount and types of lighting equipment that would have to be transported from England to do the job on such an unusual location. “Indeed it was,” says Freddie. “When I came out here on a reconnaissance trip after Christmas, having first studied the script very carefully and talked it over with David Lean, I had to assess the amount of lighting equipment and generators I would need for the job. That's an important part of the director of photography’s work estimating the minimum of equipment that will be needed, because you can’t simply send along an extra Brute or an extra generator or an extra anything. So you ask yourself which sequence will require the most equipment, and you set that as your minimum. You can't cut it too fine, however, because the director may decide, when he starts working in the location, to shift a bit of action into a large interior or make a night exterior sequence out of it — and you’ve got to have the necessary equipment right there on the spot.”

I ask him if anyone ever questions his estimate and he says, “Well, the production manager is invariably appalled at the size of the list. He says something like: ‘What, all that much, Freddie?’ and I say: ‘Yes, and that’s the minimum. A lot of cameramen would ask for twice as much.’ Actually, my minimum included 12 Brutes, plus 1OKs, 5Ks, 2Ks, Baby Juniors and even Dinky-inkies. I’m happy to say that my assessment fit the job quite correctly. We’ve now finished the sequences requiring the maximum, so that I’ll possibly be able to release some of the stuff.”

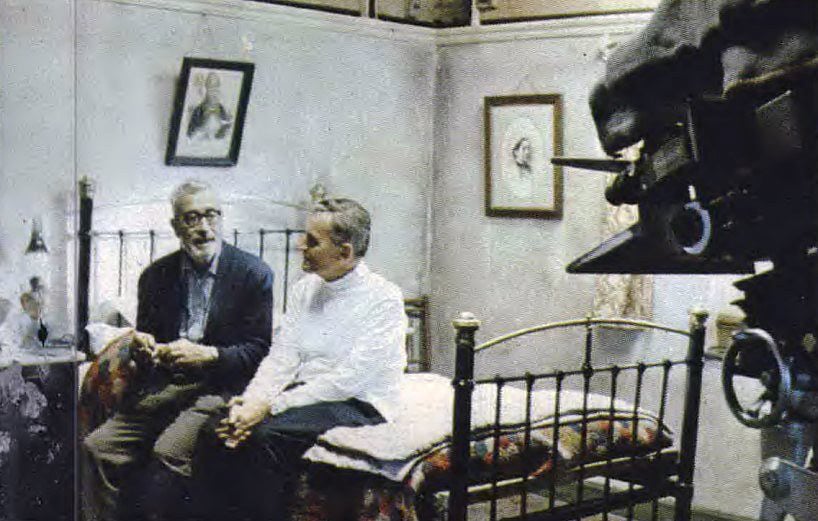

I ask him about the difficulties of lighting some of the sets having very low ceilings — especially for low-angle shots in which the ceilings will show.

“Some of the ceilings are quite low, only seven or eight feet, as in the schoolhouse living quarters,” he says. “I’m speaking of the little bedroom, sitting room and kitchen. In the classroom proper the ceiling is extra high, so I’ve been able to rig enough of the quartz soft-lights for a purely reflective, sort of shadowless light. I got the riggers from the art department to put up tubing in the ceiling so that we could hang the lights easily. In some of the buildings, such as the pub, sections of the ceiling are removable so that lights can be squeezed in among the rafters. However, just the other day we shot a very low-angle scene in the pub where somebody walked right up into camera. I’d say that 9/10ths of the ceiling was showing, so we had to light the whole thing from the floor and the windows.”

I remark that I hadn’t noticed him using any of the smaller quartz spot units, and he observes: “Well, firstly, when you’re working in the 65mm format, which has a very shallow depth of field, you’ve got to be able to stop down to T/8 in order to carry the focus — and that calls for a lot of light. That’s the serious disadvantage of working with the large film formats. Your standard lenses become sort of like telephoto lenses, with very little depth of field. Solving that problem, while trying to achieve a natural kind of lighting, calls for every ounce of experience you’ve ever had in your life. I did insist that they buy some of those new Brute arcs available in Hollywood that are much quieter than the old Brutes and weigh only about half as much. Of course, you’ve still got a smoke problem with arcs — but, to answer your question, some producers seem to imagine that you can light a set using only small quartz units. This is really ridiculous. You need the Brutes. They are the most valuable asset to making a big picture in 35mm or 65mm. You just won’t be able to do without the Brute until they invent something which will truly replace it — and do the job better. The Brute is the most valuable lamp in the film industry. Nothing else can touch it.”

Lean is a creative genius of total dedication to filmmaking. It seems to absorb him completely. Yet, when we lunch in the little stone cottage which has been set aside as his private dining room he hardly mentions film or anything to do with the industry. He talks, instead, about the space program and speaks with genuine excitement of our upcoming Apollo 11 moon-landing. Being a space-nut myself. I'm delighted at his interest.

On the set he is an aloof, almost mystical figure who moves about in an aura of creative solitude. Yet, he is sensitive to the people around him and is capable of acts of unexpected kindness.

For example, one morning I am attempting to snap an unposed color photograph of Freddie Young as he darts about the bedroom set taking light readings. The problem is that he always keeps his back to me. Noting this, Lean walks up and says, “Is there anything I can do to help you get your picture?”

I explain the problem and he says, “Well, I’ll just walk in and talk to Freddie about the scene and get him turned around so that you can get a good shot.”

He does exactly that, sitting Freddie down on the bed, full into camera while I tick off three shots.

It takes a big man to be that considerate.

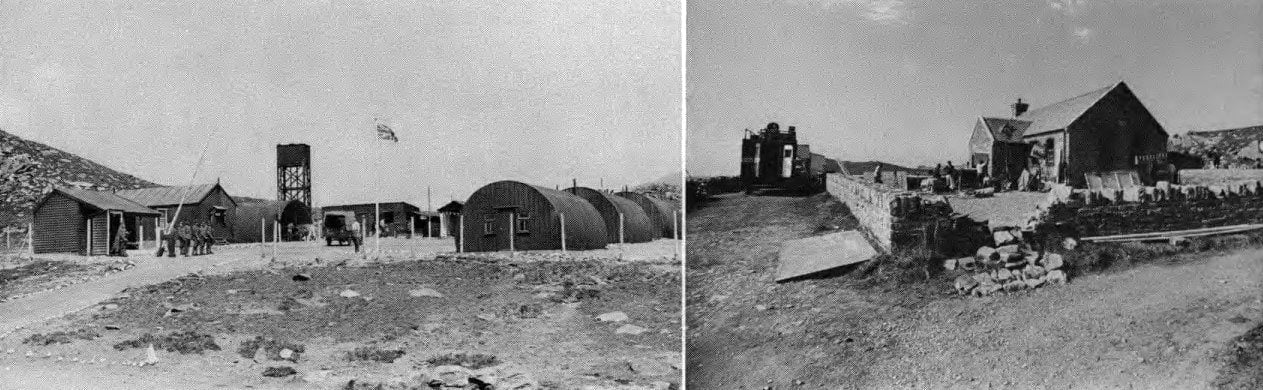

Early one morning, before shooting begins, I am given a conducted tour of the various sets that have been constructed here for Ryan’s Daughter. High on a hill overlooking the beach is an English military command post (World War I vintage), complete with commandant's quarters, ammunition dumps, barracks and quonset huts. I find that the buildings' interiors are completely dressed with props of the period and are entirely practical. It is pointed out to me that the interiors of some of the smaller rooms have been constructed with “wild” walls that can be broken out in a pinch, as well as hinged roofs that can be tilted up — but, even so, the quarters are very close.

On a nearby rise there is a stretch of stark World War I battlefield, complete with trenches and barbed wire entanglements. This was used, I am told, to shoot a short flashback night battle sequence which shows one of the characters getting wounded.

hillside outside of Dingle. Right: Exterior view of the schoolhouse, which includes practical

interiors of the classroom and the schoolmaster's living quarters.

Some distance away, there is an old barn which has been refurbished into a small sound stage with a couple of interior cover sets for emergencies. It has not been soundproofed, but I am told this wasn’t necessary because the barn is out in the middle of nowhere, far from any sources of noise and many miles remote from the routes of aircraft.

It is the village of Kirrary itself, however, which is the true masterpiece of construction. It has no false fronts and absolutely no atmosphere of a movie set. It’s more than 40 buildings are constructed of solid stone, just as they have been for centuries in this area, and are of authentic scale. Some of the interior walls, again, are “wild,” but the outside limits of the buildings are set by the parameters of the stone walls and some of the areas are so small it is a puzzlement to imagine how they can accommodate the lights, the large Super Panavision 70 camera and the actors — to say nothing of the crew. Also, assuming that you can get them all in, how are you able (working in a 65mm format) to get anything resembling a full shot inside these tiny rooms? I ask Freddie Young how he has managed to do it.

“It’s not all that difficult,” he says with typical British understatement. "We have the benefit of everything the art department can do — some interior walls that float and can be gotten out of the way. Generally speaking, we’ve been trying to get the feel that we’re within the four walls. We like to keep our feet inside and not get out beyond the fourth wall. I think that establishing shots are sort of old hat now, anyway. You don’t really need them because you move around so much that you show every part of the room at one time or another. In a pinch, we have the 40mm lens, which gives quite a wide angle in the 65mm format, but we don’t use it very often because it makes a small room look an enormous size. I really prefer never to use a lens shorter than 50mm, and most of the time we are on a 75mm. This is about the equivalent of the 50mm lens in the 35mm format, and it doesn’t exaggerate the size of the room.”

My last full day on location with the Ryan’s Daughter company is a hectic one, indeed. The weather report the night before has promised one of those “postcard” days, with blue skies and bright sunlight from dawn till dusk (which lasts until about 11:00 p.m. in these climes at the height of the summer).

The call goes out for seaside exterior shooting all day and we load into cars for the half-hour’s drive to Inch, a wide expanse of more or less deserted beach where the action is to be shot.

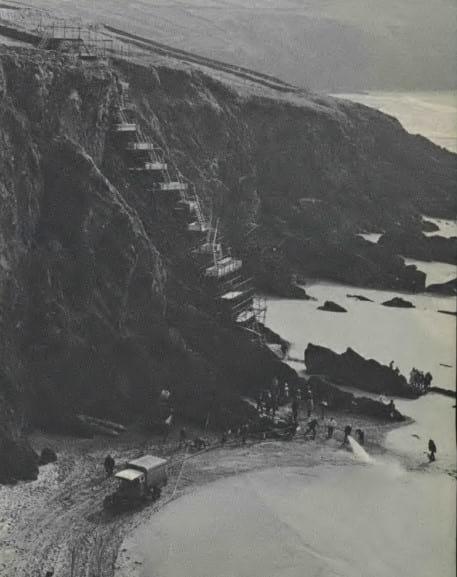

A mobile city of trailers used as dressing rooms and production offices has sprung up overnight along the beach, like a mushroom patch. Catering trucks are deployed in position around the commissary area. Down on the beach, at the foot of a cliff (and God only knows how they got it there), is a huge camera crane.

haul equipment to beach location below, as

well as multi-level camera platform

I notice on the call sheet that under “props” there is listed “a flock of seagulls” and I can’t help but wonder whether, in a case like this, you bring your own gulls or try to round up what's already there. As it turns out, one of the assistant directors, a cheerful type named “Mickey” has been appointed “seagull wrangler" and he is doomed to run about all day with a huge bag of fish enticing lazy resident seagulls up off the beach and into the air — on cue, yet. The action to be shot that day seems simple enough — various scenes, both stationary and trucking, of Robert Mitchum and Sarah Miles strolling along the beach at water’s edge.

David Lean and Freddie Young jog (they never seem to walk) up and down vast stretches of beach, selecting camera angles. Their vitality is absolutely incredible, very much like that which teenagers are supposed to have. Freddie, in his red hat and socks, seems to be in eight places at once, personally checking out every detail relating to camera. No chair-borne cinematographer he.

David, with the intense, total dedication for which he is famous, seems to jet from one end of the beach to the other, probably the fastest mile on record. There is absolutely no compromise on his part. He is out to find the very best camera angles, come Hell or (as in this case) high water.

The rapport between director and cinematographer is a lovely thing to behold — two highly individualized cinema craftsmen functioning as a single creative entity. One can finally begin to understand how Lawrence and Zhivago came into being.

The first order of the day is a trucking two shot of the principals strolling the beach, which seems simple enough, until it is discovered that, for some technical reason or other, the giant camera crane cannot be used. An emergency substitution in facilities is immediately put into effect. The Super Panavision 70 camera is mounted on a crab dolly which is then rolled onto the bed of a small pickup truck, cheek by jowl with a Brute arc. The truck is attached to two other support vehicles (one of them a mobile generator) by means of a heavy cable umbilical cord. The cable is hoisted up, and carried during a take, by just about everyone who can be pressed into service. They won't have to worry about getting sufficient exercise that day!

By the time this strange safari has trundled up and down the beach for the endless number of takes necessary to get the scene just right, it is time for lunch. Everyone stops for nourishment — except David and Freddie. These worthies, without missing a beat, are setting up on the edge (literally) of the cliff, high above the beach to shoot a long establishing zoom shot of the action that has just been filmed in the trucking shot. Plates of lunch are brought to them so that they can nibble while looking through the viewfinder and issuing orders (by means of bull-horns and walkietalkies) to the stand-ins and assistant directors on the beach below.

This is a scene that calls for seagulls, swarms of them, lazily soaring through the sky as a living backdrop for the actors. The hapless Mickey, with his bag of fish, stands at water's edge ready to wrangle his feathered friends into the air at the cry of “Action!”

It requires about eight takes to get the scene on film to Lean’s satisfaction, and prior to each of these Mickey (who informs me that he has become an expert on seagull behavior) runs about scattering fish goodies in the surf. Then, if and when the stupid birds soar into the air, he has to do the 100-yard dash to get himself out of the composition. There should be a special Oscar for this sort of thing.

The rest of the 12-hour day is taken up with more trucking shots of the beach stroll — individual closeups this time — and then Lean wraps it up just as I discover that I’m sunburned to a crisp.

Bob Mitchum invites me to have dinner at his digs, a cozy private tenroom hotel he shares with his long-time stand-in, Harold Sanderson, and one of the other stand-ins. He cooks the dinner himself — and with a genuine gourmet flair. Then we talk philosophy until 3 a.m. It’s a stimulating experience to trade ideas with such a keen intelligence and I can’t help thinking how underrated this sensitive man is in the eyes of the world — both as an actor and as a person.

When I leave Dingle the next morning it is with sincere regret — not only because of the warmth and friendliness of the Gaelic-speaking natives, but because it has been such a rare privilege to watch a pair of top-notch filmmaking “pros” at work.

Freddie Young lends me his own driver, a lad named Pat (What else?) to drive me to Shannon Airport. We say our goodbyes and I wish him luck with the remainder of the shooting.

“Everything will be all right,” says Freddie. "We have a dedicated director to work for and we have some marvelous artists. We are all just doing the best we can, and I think it will be a very fine picture.”

Young earned his third Academy Award for Best Cinematography for his expert work in this picture — following previous wins for Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago.

Among many other honoree throughout his illustrious career, he was presented with the ASC International Award in 1993.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.