A Look Back at Out of the Past

A retrospective look at this RKO film noir classic, shot with style by Nicholas Musuraca, ASC.

Out of the Past was one of about 360 feature productions made in Hollywood during 1947. It was released into a booming market in which 90 million Americans were paying admissions each week at 19,107 theaters to create domestic revenues of $1,565 billion. The foreign market accounted for an additional $900 million.

RKO-Radio, which produced Out of the Past, released 39 features and 84 one and two-reel short subjects that year. Although 1947 was a great year for most of the studios, RKO went into the red to the tune of $1.8 million. While this may sound like small potatoes by today’s standards, it represented the production cost of three “A” pictures or a dozen profitable “B’s”. Out of the Past was well-advertised and had names that meant something at the box office, assuring it a wide enough audience to put some black ink on the books. It also has emerged from that formidable mass of pictures as one of the highlights of its time, a picture whose charm becomes more apparent with each viewing.

It is what was called, in those days, a “hard-boiled melodrama.” Certain pictures of this kind today represent a sort of sub-genre known as film noir, a designation created in 1946 by a French critic, Nino Frank, but only recently recognized in Britain and America. These films reflect the growing pessimism of the war years and their aftermath, depicting with cynicism an awareness of dark forces engendered by a world being consumed by greed and corruption. Out of the Past has become recognized as one of the prime examples of noir films.

Each of the major studios imparted to their pictures a distinctive style recognizable to even a semi-alert moviegoer. While all of the studios contributed noteworthy noir films, the leaders were Warner Brothers and RKO. The Warner approach — best exemplified by The Maltese Falcon and The Big Sleep — emphasized sharply drawn images photographed from often bizarre angles, fast-paced direction emphasized by rapid cutting and swift transitions, gaudy musical scoring, and strong central characterizations by the likes of Humphrey Bogart, Edward G. Robinson and James Cagney. The RKO style was almost the opposite: underplayed performances, photography themed more to convey pictorial beauty and intangible menace than startling dramatic punch, unobtrusive music that emphasizes mood rather than action, and comparatively leisurely cutting. Each approach gave us its share of masterworks.

Out of the Past was generously financed and shot in 64 working days (an unusually long schedule at the time), mostly on the sound stages at RKO’s Hollywood studio and the Pathé lot in Culver City. There are extensive location scenes with several of the principals made in the Lake Tahoe area on the California-Nevada boundary and second-unit work from Acapulco, New York and San Francisco.

Much of its excellence can be credited to its author, Geoffrey Homes, a novelist and screenwriter whose real name was Daniel Mainwaring. After a grueling year in which he wrote a half-dozen scripts for Pine-Thomas Productions, makers of low-budget action films for Paramount release, Homes retreated from the studios long enough to write his first novel in several years, Build My Gallows High. He consciously gave it some of the qualities of a book he admired greatly, Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon. William Dozier, production chief at RKO-Radio, not only bought the property but hired Homes to develop the screenplay for producer Warren Duff, himself a screenwriter of note.

Duff, not quite satisfied with Homes’ first draft, assigned James M. Cain, then America’s most celebrated writer of hard-boiled novels (Double Indemnity, The Postman Always Rings Twice, Mildred Pierce), to rewrite it. Later, Frank Fenton, one of the studio’s more dependable contract scenarists, revised the script further. Eventually, it was Homes who wrote the final shooting script, which follows the book fairly closely.

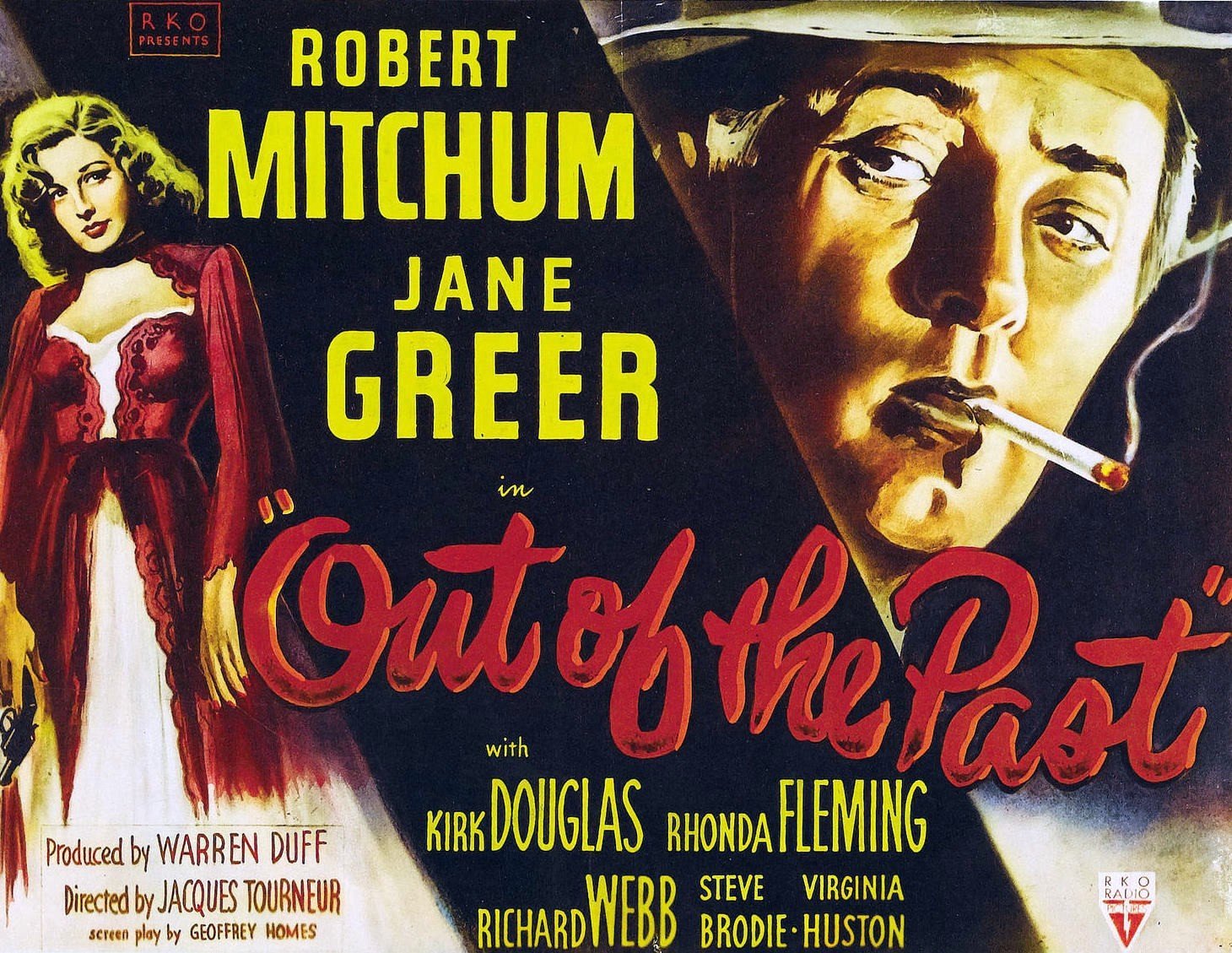

The film opens in the town of Bridgeport, California, where Jeff (Robert Mitchum) is eking out a living running a service station. A visiting mobster, Joe (Paul Valentine), recognizes him as a former private investigator who double-crossed a big-time crook, Whit (Kirk Douglas). Jeff explains the situation to his fiancee, Ann (Virginia Huston), and the story of Jeff’s past is shown in flashback:

Whit was shot and wounded by his inamorata, Kathie (Jane Greer), who fled to Florida with $40,000 of Whit’s money and then dropped out of sight. Whit hired Jeff and his partner, Fisher (Steve Brodie), to track her down. After finding Kathie in Acapulco, Jeff believed her story that she didn’t take the money and that she wounded Whit in self-defense. He reported to Whit that Kathie had escaped and, blindly in love, helped her to hide out. When Fisher tracked them down and tried to make a deal for part of the money, Kathie killed him and conned Jeff into hiding the body. Kathie then abandoned Jeff, who eventually went into hiding at Bridgeport.

Ann suggests he try to patch things up with Whit. Returning to the city, he finds that Kathie is living with Whit again. Whit tells him all will be forgiven if Jeff does a job for him of stealing some incriminating papers held by a crooked accountant named Eels (Ken Niles). Jeff does the job and finds that he has been framed by Whit and a glamorous secretary, Meta (Rhonda Fleming), for the murders of Eels and Fisher. His possession of the papers makes it possible for him to make a deal with Whit to get him off the hook and let the deserving Kathie take the rap.

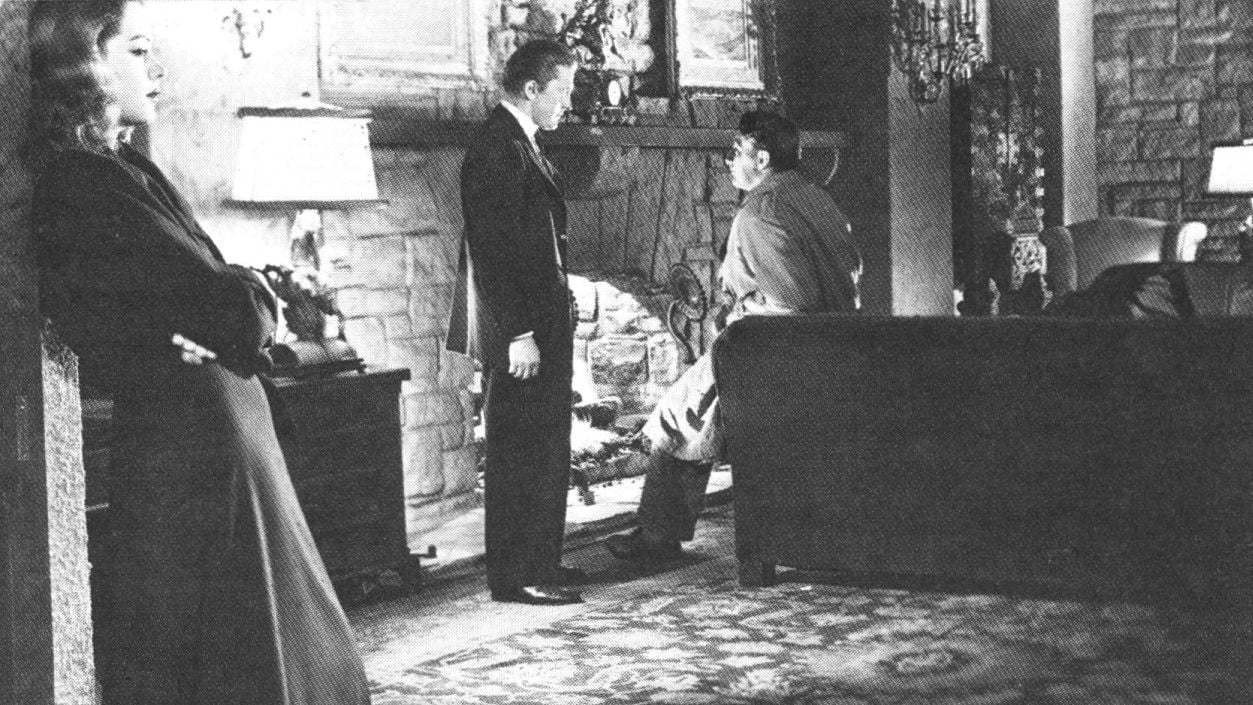

composition make it clear that all is not well between them.

Whit’s trigger man, Joe, stalks Jeff in the mountains near Bridgeport. The Kid (Dickie Moore), a mute youth who works at Jeff’s station, sees Joe on top of a cliff, drawing a bead on the unsuspecting Jeff. Using a fly rod, The Kid hooks Joe and yanks him over the edge to his death. Telling Ann she should forget him, Jeff returns to see Whit and close the deal. He finds, to his horror, that Kathie has killed Whit. She urges him to flee with her to South America. He agrees but secretly notifies the police. Kathie and Jeff are killed when she tries to drive through a police ambush.

The dialogue — especially from Jeff — is terse and witty, tinged with ironic humor and flavored by a world-wise cynicism. It was tailored to fit the screen personality of Humphrey Bogart, whose performances as Sam Spade, Rick the American and Philip Marlowe had established him as the foremost portrayer of the tough-yet-sentimental romantic. Homes personally delivered the script to Bogart, who was anxious to do the film, but Warner Bros. refused to loan him out to RKO. Dick Powell, who was under contract to RKO and had done a superb job as Philip Marlowe in Murder My Sweet, fell heir to the role and was featured in the advance advertising to the trades. By the time production was ready to commence, young Robert Mitchum, who had played some minor roles at the studio, had scored a huge success in The Story of G. I. Joe and had become a formidable box-office name. Mitchum was given the part.

That Bogart or Powell would have created a memorable character goes without saying. However, the dialogue works superbly with Mitchum’s sleepy-eyed, offhand delivery. When the beautiful but poisonous Kathie asks Jeff if he has missed her, he murmurs, “No more than my eyes.” When his small-town fiancee opines that Kathie can’t be all bad because no one is, he tells her, “She comes closest.” To Kathie’s question, “Is there any way to win?” Jeff hedges: “There’s a way to lose more slowly.” As for the ultimate danger: “I don’t want to die, but if I have to, I’ll die last.”

Jane Greer, co-starring as Kathie, was a former RKO starlet. (Remember studio starlets? They were pretty contract players who did minor acting jobs and posed for innumerable publicity stills). She is excellent in a difficult characterization that calls for equal parts of sex appeal, seeming innocence and malignant evil.

For the principal supporting roles of Whit and Meta, it would have been difficult to have improved upon Kirk Douglas, who at the time was playing nothing but villains, and Rhonda Fleming, a statuesque beauty then under contract to David O. Selznick. When RKO reissued the picture in 1953, their names were moved to equal billing with Mitchum and Greer above the title.

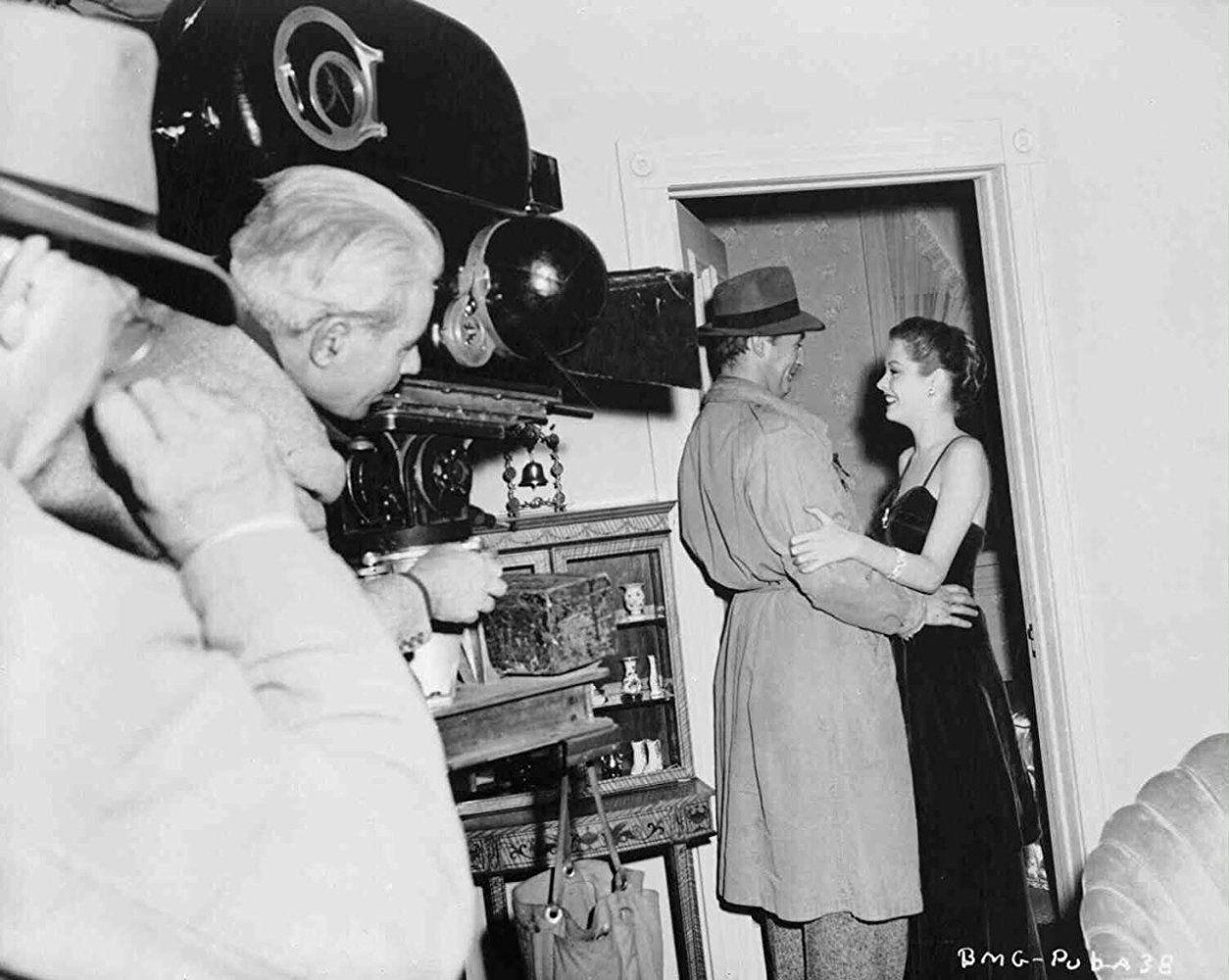

The picture united for the third and final time one of the most remarkable director-cinematographer teams the industry has produced: Jacques Tourneur and Nicholas Musuraca, ASC.

Born in Paris in 1904, Tourneur came to the United States with his father, the noted director Maurice Tourneur, in 1912. He entered the industry in 1924 as an office boy at Metro Pictures, parent organization of MGM. Later, he became a continuity clerk and an actor. Returning to France, he directed several films during the early 1930s before rejoining MGM as a director of short subjects and second units. With Val Lewton, he directed the siege of the Bastille sequence in A Tale of Two Cities (1937). Graduating to features in 1939, he directed several minor productions at MGM before being lured to RKO by Val Lewton, who had signed a producing contract there. The first Lewton-Tourneur feature was the celebrated The Cat People (1931), a subtly beautiful picture which proved that horror pictures needn’t be horrible. It was photographed by Nick Musuraca in a brilliant manner in which audiences were forced to imagine what terrors might lurk in the cleverly placed shadows that lay in every setting. I Walked With a Zombie — despite the crowd-teasing title, a work of real artistry — and The Leopard Man, which was also photographed by Musuraca, followed. The studio then graduated Tourneur to high-budget productions, of which the fourth was Out of the Past.

Musuraca was born in Italy in 1892 and began his film career at Vitagraph Studio in New York City in 1913, first as a projectionist, then as a cutter and assistant director. Vitagraph’s co-founder, artist and director J. Stuart Blackton, made him a first cameraman (a Silent Era title for a director of photography) in 1918. After several years, he moved to California to join the British-backed Robertson-Cole Studio located at the corner of Melrose and Gower in Hollywood. When R-C went broke, he remained with its successor, FBO Productions, shooting numerous silent Westerns starring Bob Steele, Buzz Barton and Tom Tyler. When RKO-Radio took over the studio in 1928, Musuraca shot a few “indoor” pictures before being assigned to the Tom Keene Westerns.

When the Keene series terminated in 1933, Musuraca got a chance to prove his versatility by shooting a wide variety of films, ranging from low-budget “quickies” to such prestigious productions as The Swiss Family Robinson and Tom Brown's School Days. One interesting assignment in 1940 was an artistic “B” mystery film, Stranger on the Third Floor. Musuraca’s striking use of chiaroscuro lighting in this unusual psychological drama anticipates the singular pictorial style he brought to the Lewton-Tourneur pictures several years later, as well as three other Lewton productions not directed by Tourneur: The Ghost Ship, Curse of the Cat People and Bedlam.

Tourneur and Musuraca worked well together. Tourneur, husky but mild-mannered, was usually relaxed and seemingly devoid of temperament on the set, always keeping his actors at their ease and relying heavily upon Musuraca’s know-how to produce the combination of mystery and visual beauty essential to these films. The acting is deliberately underplayed, in Out of the Past keyed to the nonchalant style of Mitchum — even that of the usually extroverted Kirk Douglas. Jane Greer has said that Tourneur’s direction “was very simple to understand,” and that he often asked the players to seem “impassive.”

Samuel Beetley, who edited Out of the Past, says that Tourneur “was one of the finest directors I ever worked with. He was artistic and he knew what the editor needed.” Beetley remarked upon one subtle “touch” that lent distinction in Tourneur’s films: “He always insisted upon never returning to the same camera angles when intercutting scenes.”

Simplicity and practicality were the keynotes of Musuraca’s lighting. In an interview for American Cinematographer, February 1941, he stated that “...while theories may be fine, the best way to do a thing is usually the simplest — and we can always find that simplest way if we reason things out looking for simplicity and logic instead of technical window-dressing.”

Musuraca did not agree with the cinematic convention that heavy drama must be lit in a low key, comedy in high key, and romance in soft focus, but that the style should be determined by the logic of the scene. “For example, a vast amount of real-life drama occurs in hospitals, and a modern hospital isn’t by any means a somber appearing place,” he pointed out. “Everything is light-colored and glistening; what’s more, everything is pretty well illuminated — trust these medical men to see to it that there’s enough illumination everywhere to prevent eyestrain. So why should we always have things somber and gloomy when... we try to portray sad or tragic action in a hospital?

“In the same way, if there’s no logical reason for it, why should comedy always be lit in a high key? Sometimes your action may really demand low-key effects to put it over! In making Little Men [1940], we had such a scene. The scene showed George Bancroft sitting at his desk, reading; it was a night effect. While he is engrossed with his study, Jack Oakie tiptoes in through the door and hides behind the door — unknown to the professor — who calmly gets up and goes out, still unaware that anyone is in the room.

“Luckily, the period of the picture — the late 19th Century — helped me. For at that time and in the places represented, rooms were illuminated with the old-fashioned coal-oil lamps. In the long shots of this sequence, we established two of these lamps: one a desk lamp, illuminating the professor’s work; the other a lamp on a table, casting its glow of light in another portion of the room. The intervening areas I left — as they would be in real life — in deep shadow. Oakie was seen entering the room; then as he hid behind the door, he was lost in the deep shadow. The audience could enjoy the humor of the situation far better because the lighting helped them to believe the action.”

Musuraca believed that cinematography had become unnecessarily complicated. “All too often we’re all of us likely to find ourselves throwing in an extra-light here, and another there, simply to correct something which is a bit wrong because of the way one basic lamp is placed or adjusted... If, on the other hand, that one original lamp is in its really correct place and adjustment, the others aren’t needed. Any time I find myself using more than the ordinary number of light sources for a scene, I try to stop and think it out. Nine times out of ten I’ll find I’ve slipped up somewhere, and the extra lights are really unnecessary. If you once get the ‘feel’ of lighting balance this way, you’ll be surprised how you’ll be able to simplify your lightings. Usually, the results on the screen are better, too!

“The same thing applies to making exterior scenes. One of most common sources of unnecessary complication is in overdoing filtering. Just because the research scientists have evolved a range of several score filters of different colors and densities isn’t by any means a reason that we’ve got to use them — or even burden ourselves down with them. On my own part, I’ve always found that the simplest filtering is best. Give me a good yellow filter for mild correction effects, and a good red or red-orange one for heavier corrections, and I’ll guarantee to bring you back almost any sort of exterior effects — other than night scenes — that you’ll need in the average production. My own choice is an Aero 1 for the lighter effects, and a G or sometimes a 23-A for heavier effects.”

Obviously, Musuraca’s deep shadows were an integral part of the atmosphere pervading much of Out of the Past, in which the fear of death is imminent from first to last. Even the exteriors photographed in the natural beauty of the Tahoe area convey menace as well as charm. The hard-lit textures of trees and granite in sun and shadow emphasize the danger of an assassin stalking his prey even at an idyllic fishing stream. Jeff’s comment, “You don’t go fishing with a .45,” echoes the ambiguity of the situation.

Several scenes are enhanced by realistic visual effects made under the supervision of Russell A. Culley, ASC, a pioneer effects cinematographer who had recently taken charge of that department following the retirement of Vernon L. Walker, ASC. Rear-projection process shots were utilized to combine the Mexican location backgrounds with studio photography of Mitchum and Greer. Matte paintings provided architectural and scenic details such as the exterior of Douglas’ palatial home.

Roy Webb, one of the best and most prolific composers of film music, provided the subtle underscore which helps to hold the plot complexities together. Webb’s music was integral to Stranger on the Third Floor, most of the Lewton films, Murder My Sweet, Notorious, Cornered, The Spiral Staircase, The Locket, Crossfire, They Won't Believe Me, and Riff-Raff — in other words, most of the best of RKO’s ventures into mystery and mayhem during the 1940s. To say that the Hungarian-born composer had a flair for this type of music is an understatement. He created music that sounds the way a Musuraca night shot looks: suggestive, atmospheric, dramatic. While it always strengthens the visuals, it never overwhelms the senses. His work in these films was widely imitated.

After production was completed, the original title, Build My Gallows High, was given to Dr. Gallup’s Audience Research, Inc. for testing. Their poll indicated that an overwhelming number of potential customers were put off by the morbidity of the title. The picture went into release as Out of the Past in November 1947 and was well received by the trade publications and the public, although there were some objections to the tragic ending. Although Jeff is a sympathetic and even praiseworthy character caught up in the machinations of others and pushed unwillingly into criminal collusion, it is doubtful that the Production Code of self-censorship would have permitted any other kind of ending. Curiously, the censors who demanded punishment for Jeff seemed unconcerned that The Kid went unpunished for killing the gunman.

Coburn.

Shortly after the picture was released, Musuraca complained that he was being typecast as a specialist in mystery films. He did photograph several later films in that vein, but the rest of his career in movies and TV production gave him plenty of opportunities to display his versatility with a wide variety of subjects. He died in 1975 but remains an almost legendary name — mostly because of his work at RKO.

Tourneur’s career continued in high gear over the next decade, with highly rewarding assignments. In 1957 he went to England, where he made the much-honored Night of the Demon (U.S.: Curse of the Demon), a return to the type of films he made with Lewton. After that, his work in Italy and the United States was wasted on projects unworthy of his talents. He died in 1977.

There is a curious fact about the would-be arbiters of taste and molders of opinion: most pay lip service to originality while bowing deeply to fashion. At the time Out of the Past was released, it received only perfunctory critical attention, being viewed by all but the trade press as just one more well-made melodrama with too many killings and a storyline generally characterized as “confusing.” In recent years, however, it has been reappraised by many of the same critics and their successors and accorded an exalted status, not because it has changed with age but because it fits snugly into a category which — belatedly — is “in.” Once removed from that handy pigeonhole labeled film noir, the picture is exactly what The Hollywood Reporter’s critic called it after its preview in 1947: “Solid, entertaining melodrama which will enjoy a profitable box-office payoff... For the public, this is the kind of satisfying show which for years has been the industry’s bread and butter.”

Mighty nourishing it was, too