Personal Hell: The Sacred Iconography of Jacob’s Ladder

Cinematographer Jeffrey L. Kimball, ASC summons a vision of the afterlife in Adrian Lyne's 1990 horror classic.

Jacob’s Ladder opens on a hazy, humid evening in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, 1971. A platoon of U.S. Army soldiers linger in the shade of canvas tents and grass roof huts, smoking, swatting at flies, napping, passing their time in purgatory with grass and childish jokes. Among them is Jacob Singer (Tim Robbins), a private first class his comrades call “Professor” on account of college degrees.

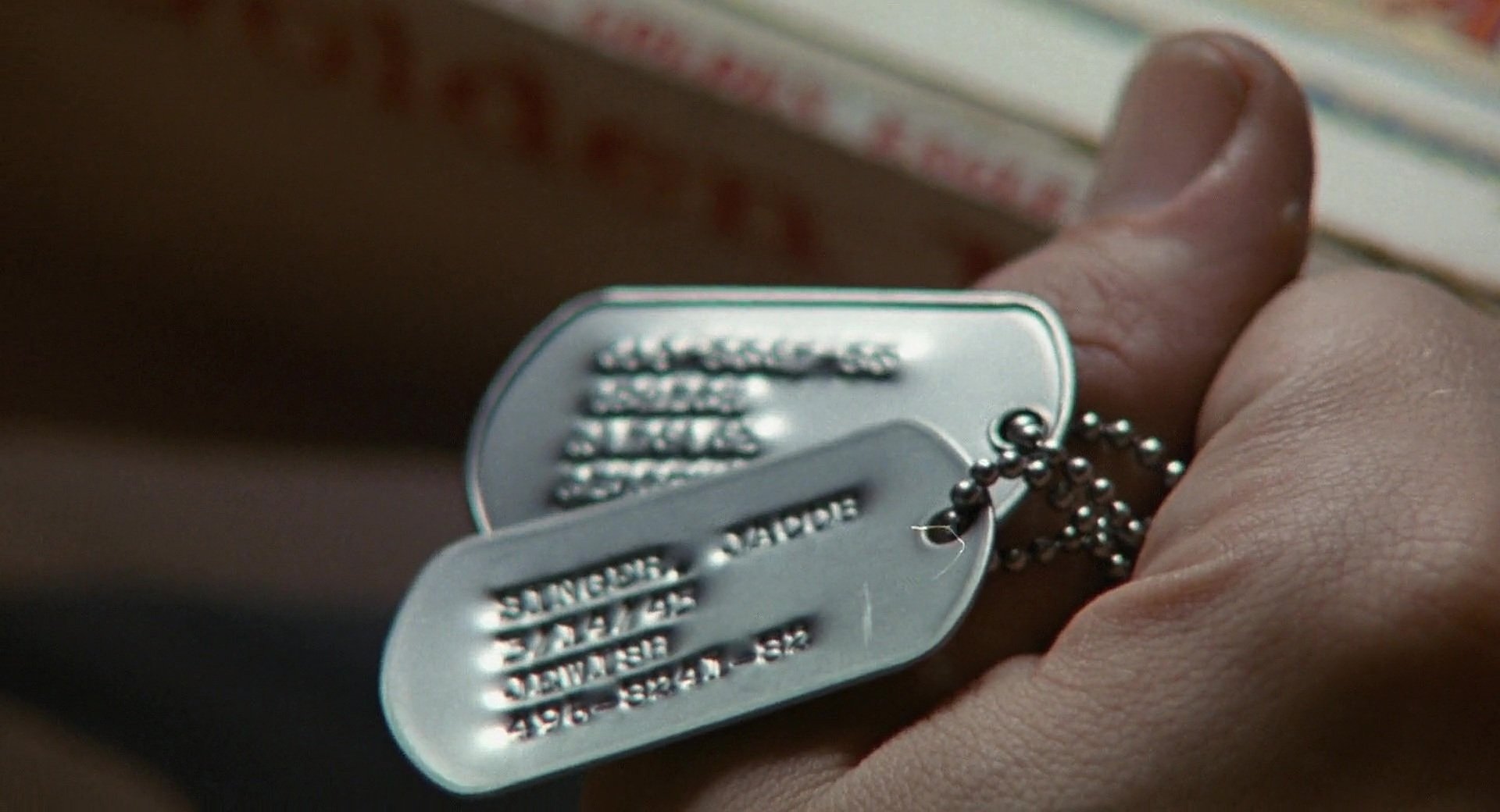

Along with their dog tags, some of the soldiers wear pendants around their neck: a peace symbol, a Star of David, a lucky horseshoe. Jacob's necklace bears the symbol for ahimsa, the Jain Dharma principle of nonviolence.

In any other film, these details could be considered minor references, but here they are just a few of the many instances in which Jacob’s Ladder uses sacred imagery to tell the story of a broken man desperately clinging to the shattered fragments of his past life.

Without warning, the camp is attacked by an unknown enemy. All hell breaks loose. Some of the soldiers begin to convulse and shake as fire and brimstone rain from the sky. Men are eviscerated and dismembered.

Jacob escapes into the jungle. In a POV shot, he’s ambushed and bayonetted in the gut by an unseen attacker. He falls to the ground, and with a match cut, awakens on a New York City subway train three years later. He’d fallen asleep reading a paperback copy of Albert Camus’s existentialist novella The Stranger and missed his stop. His right hand rests on his abdomen, where he'd been stabbed.

Jacob steps off the train and finds that the exit from his platform is locked, so he must cross over to the other side to get out. As he steps onto the tracks, another train suddenly barrels toward him. He dives out of its way, catching a glimpse of ghostly faces through the windows as it roars by.

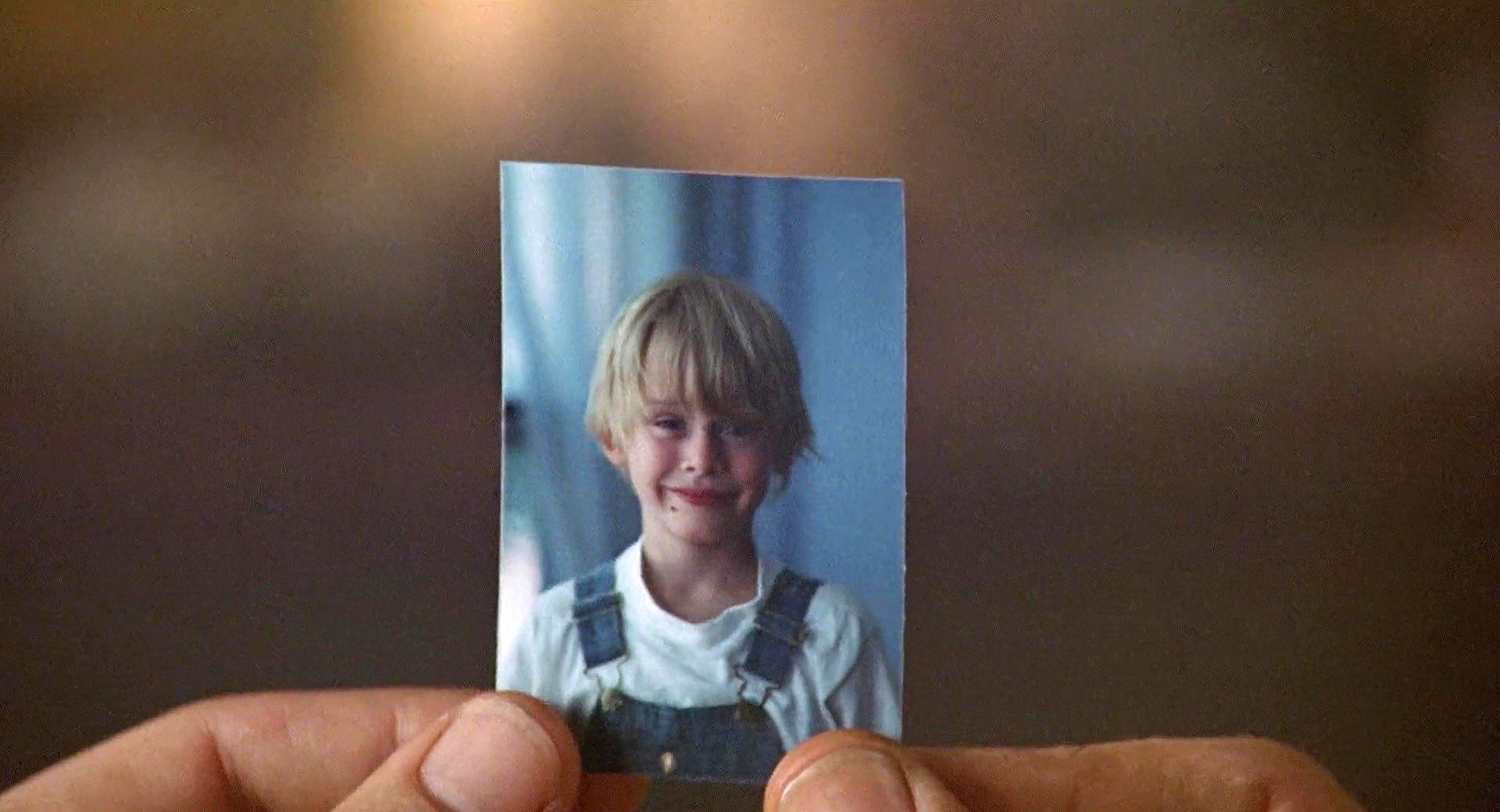

Jacob is now a veteran and a postal worker, living in a cozy Brooklyn apartment with his girlfriend Jezebel (Elizabeth Peña). It's revealed that prior to the war, he’d been a doctor, married to another woman, Sarah (Patricia Kalember), and the father of three children, one of whom, Gabe (Macaulay Culkin), was killed in a tragic auto accident.

The majority of the film’s directly religious references are tied to Judeo-Christian beliefs. (The title itself is a nod to the vision of Old Testament patriarch Jacob, who saw a ladder leading from the earth up to heaven.) Jacob and Jezzie’s apartment is a veritable reliquary of spiritual objects d'art: a Christian cross, crossed again with a pair of swords hangs on the wall next to the window. A replica of Hugo Rheinhold’s Ape with Skull is perched on Jacob’s desk, the open book at the primate's feet inscribed with the words "Eritis sicut Deus..." which translates to "You will be like God..." The rest of the page is ripped away, omitting the last part of the sentence "...scientes bonum et malum." Knowing good and evil.

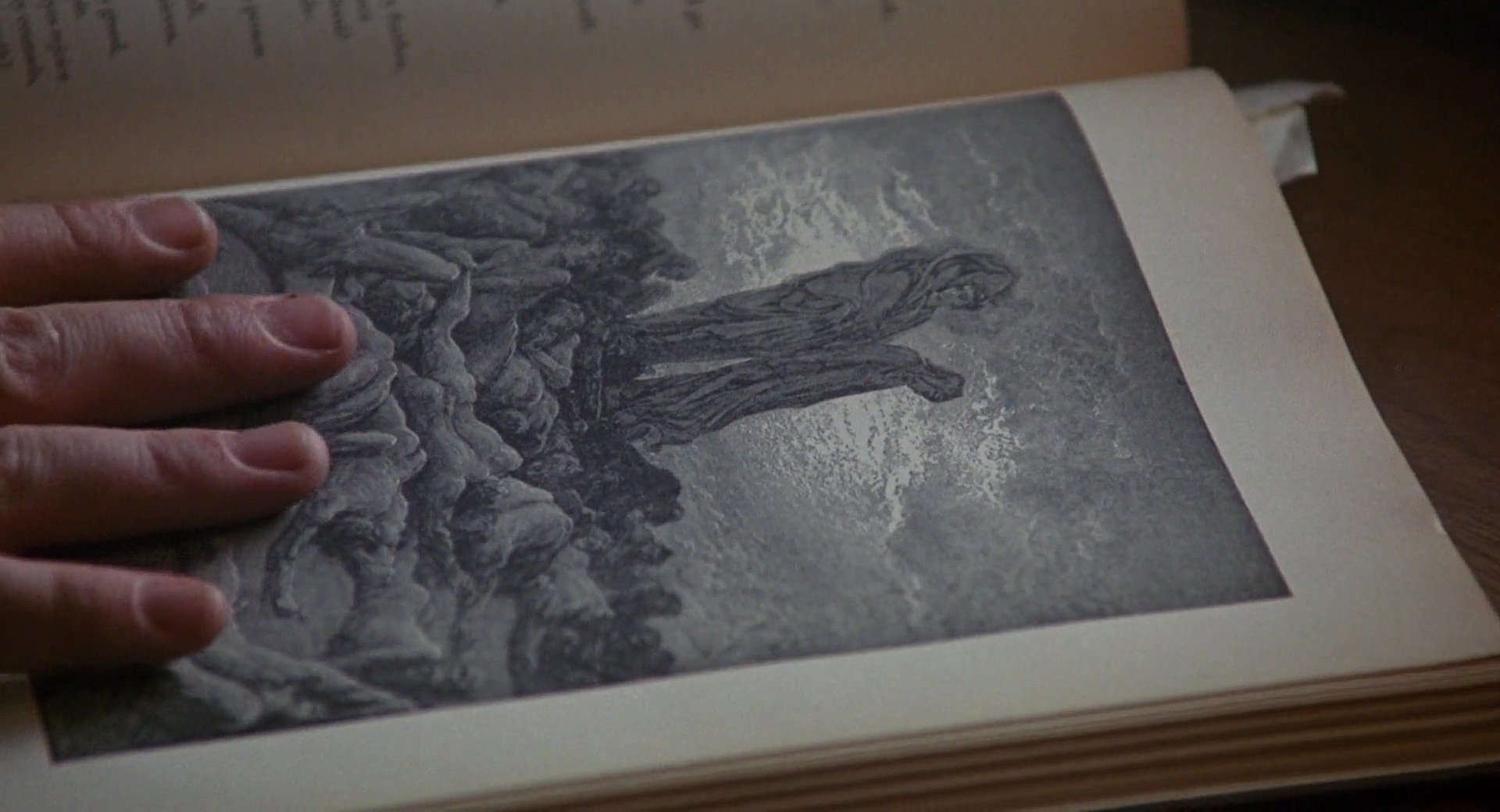

Prayer beads are draped over the shelf on the headboard, next to a candlestick base in the image of Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker (originally conceived as a likeness of poet Dante Alighieri in the sculptor’s masterwork, The Gates of Hell).

Next to the bed is a shelf lined with books like Savage God and The Magical Philosophy, while elsewhere in the apartment A Witches Bible Volume I: The Sabbats, Demonology, The Roots of Evil and Dante's The Divine Comedy are interspersed with academic texts on sociology and psychology.

These objects provide insight into the psyche and soul of a man concerned with the origins of human nature, and it’s this curiosity that drives him to investigate the relationship between his demonic visions and the revelation that he and his platoon were the subjects of a military psy-op gone wrong.

The filmmakers use several effective techniques to break down the barriers of Jacob’s reality, in particular, editor Tom Rolf’s jump/smash/match cuts between Jacob’s medevac in Vietnam, his horrific visions and his post-war life in New York City.

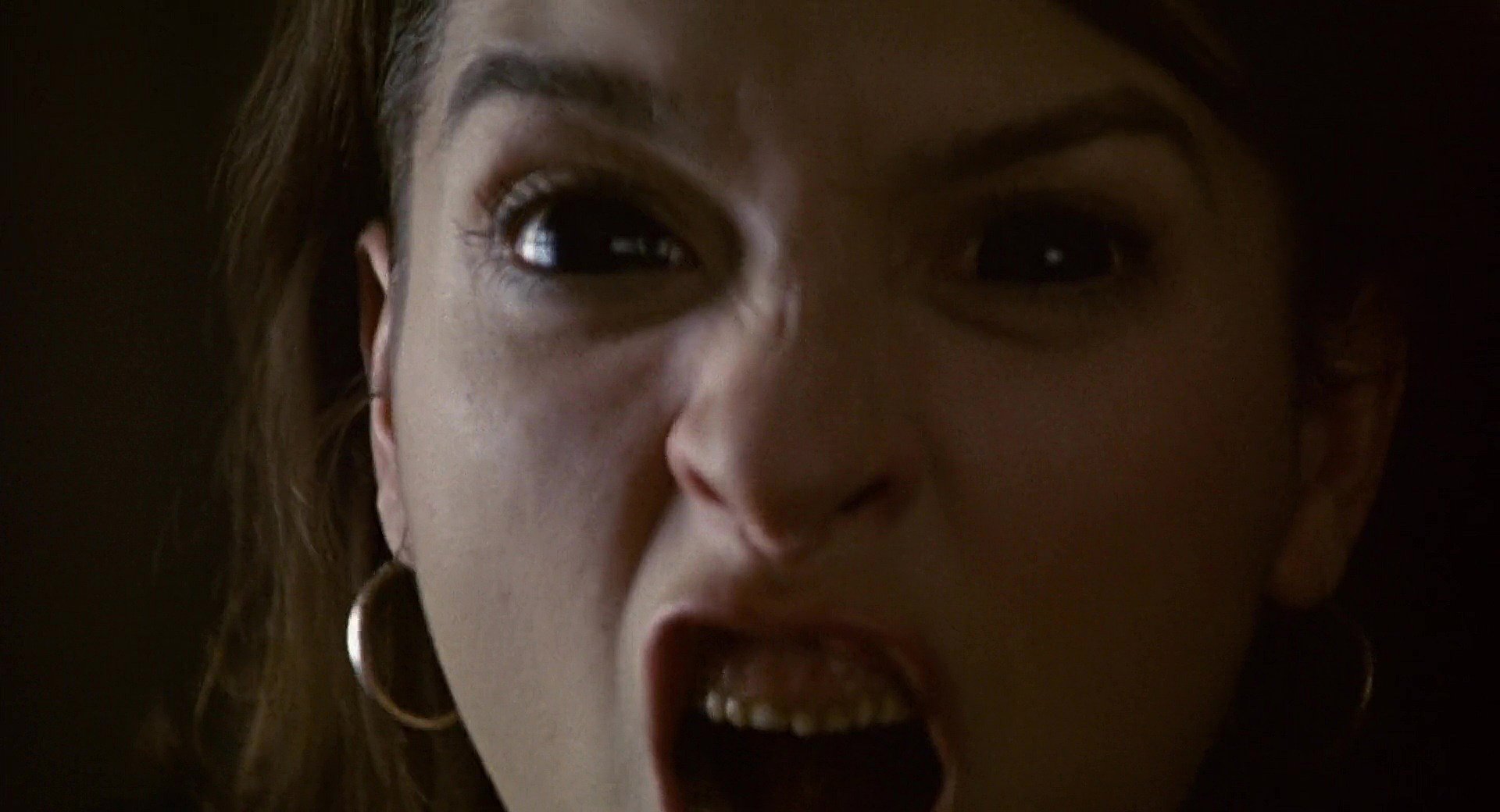

Many of the demons are portrayed as half-human ghouls with obscured and contorted faces, horns and leathery appendages protruding through broken skin, though some all-out monsters do appear. Makeup effects were supplied by J. Gordon Smith's Toronto-based FxSmith company. The demons' vibrating effect was achieved by under-cranking the camera to 4 fps for playback at 24 fps.

"All through the movies you're dealing with demons and angels and hell and heaven, and I spent a year, maybe more, trying to wrestle with how to do it — how to do a devil with horns and not make people laugh," said Lyne in a contemporaneous interview (Cinefantastique, Dec '90). "I tried to make it all human-based — sort of thalidomidey — fleshy, horns from the bone, a tail that looks a little like a schlong. I didn't want these things easily dismissed as too familiar. I did a lot of shaking, vibrating, tortured things."

Religious symbolism is woven so throughly into the tapestry of the film's narrative that one begins to recognize familiar images where they were perhaps not intended, such as the scene were Jacob goes into shock after witnessing a vision of Jezzie and a demon. His temperature skyrockets, and Jezzie rallies the help of two neighbors to lift Jacob into a bathtub full of ice water.

The camera is tight on Jacob's flushed, passionate expression. His head lolls to one shoulder. His outstretched arms are supported by the neighbors as Jezzie looms anxiously in the backround. When they lift him into the tub their arms fully encircle his body, the way Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus lower the body of Christ down from the cross in the popular Christian motif. (A similar mood is struck in Caravaggio's The Entombment of Christ.)

Jacob's only solace is in his visits with Louis (Danny Aiello), the smiling, rotund chiropractor whom Jacob describes as an “overgrown cherub.” Louis's office is a sanctuary filled with soft white light streaming in through a set of bay windows and Tiffany stained glass.

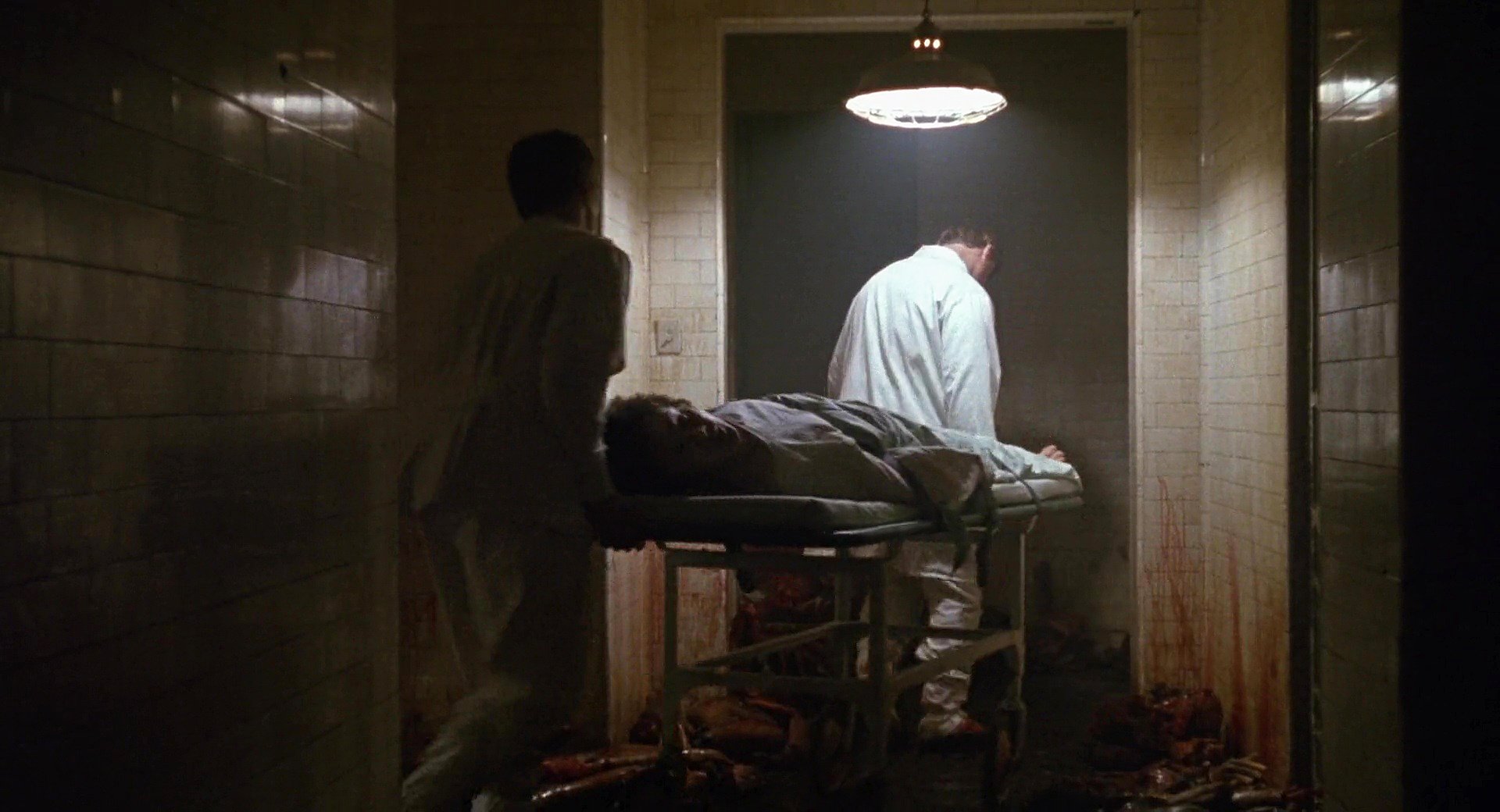

Jacob's inquiries into the possibility that he and the other soldiers were unwilling test subjects in a murderous wargame gets the attention of U.S. Government agents, who ambush and threaten him. Jacob escapes capture by throwing himself from their moving vehicle, but severely injures his back. He's taken to a hospital, the bowels of which is populated with a host of tortured souls.

"I tried to use images from Francis Bacon — tortured, blurred shots, red streaks and sharp pieces which, when you freeze frame this stuff, looks just like Bacon's drawings," said Lyne (Cinefantastique, Dec '90).

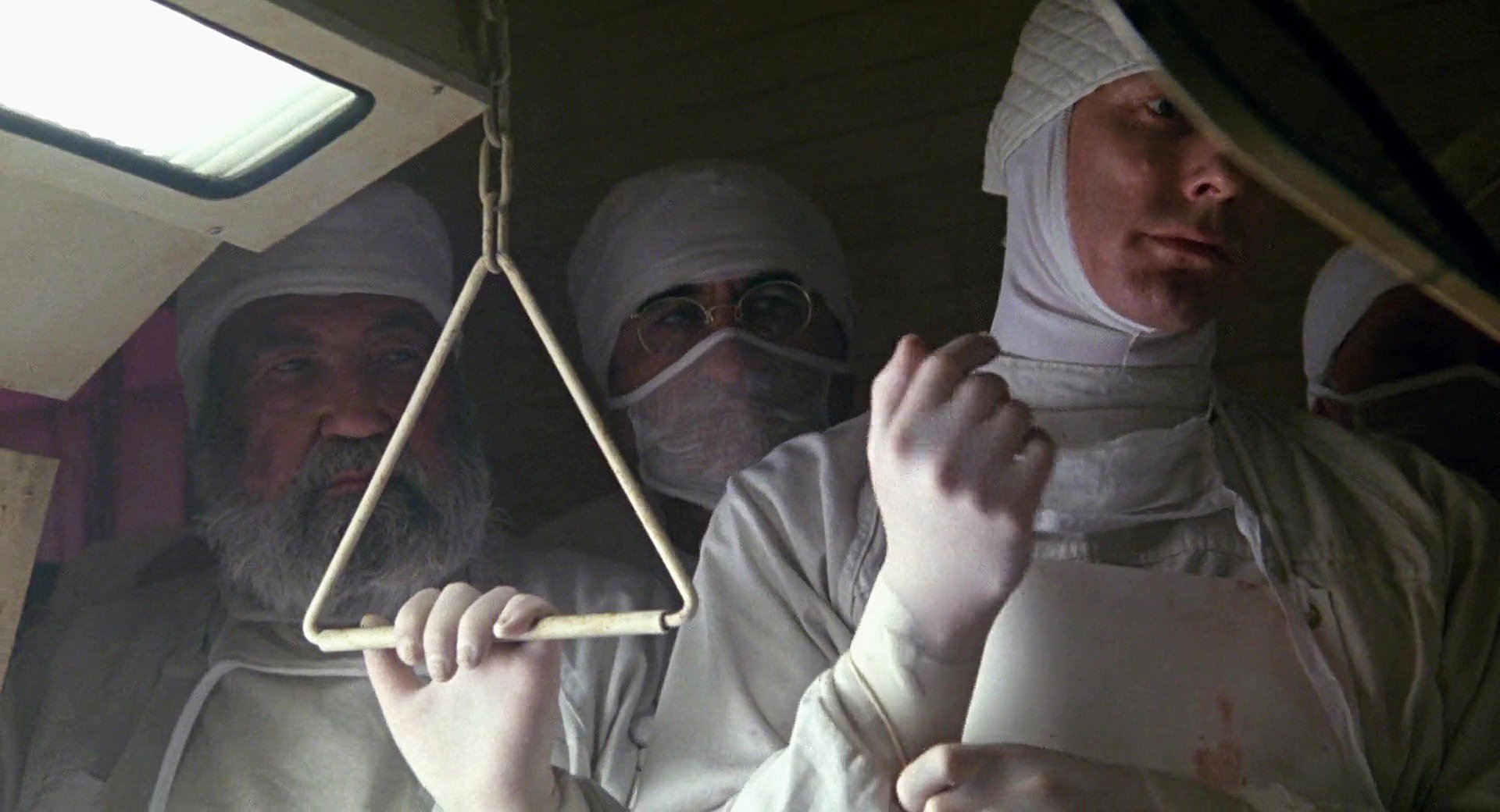

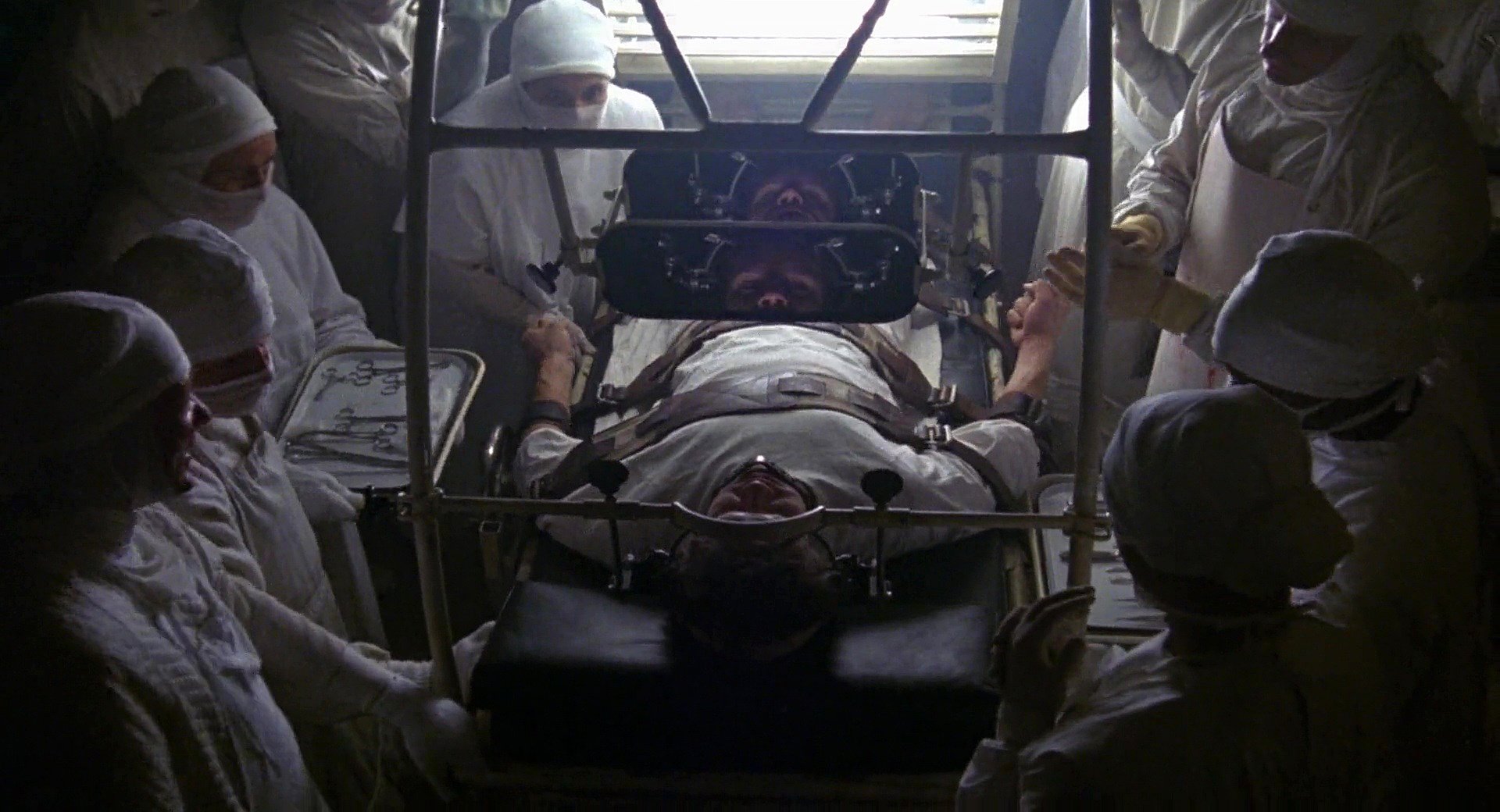

Jacob is strapped to a reclining operating table and his head is screwed into a medical halo. The operating lamp bathes him with light, which reflects off his body and onto the attending doctors lurking at the edge of darkness in a macabre twist on Rembrandt's The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp. Jezzie, in a surgical gown, preps a wicked-looking syringe then hands it to an eyeless demon, who plunges the giant needle into the middle of Jacob’s forehead in an attempt to purge his memories and ultimately, his will to live.

Cinematographer Jeffrey L. Kimball, ASC's striking photography possesses the tones and textures of a Renaissance-era painting. Optically, the film has a deep-focus quality, with atmospheric perspective used to achieve a sense of depth by contrasting dark foregrounds and light backgrounds filled with steam, haze and smoke.

Additionally, light is diffused at the source, creating a sfumato effect through which tones and colors gradually shade together to produce soft outlines and hazy forms.

Chiaroscuro lighting enhances textural qualities with deep shadows.

Jacob awakes in the hospital, doped up and in traction, unsure of what he's experiencing is real or a dream. Louis storms in, all righteous fury. Untangling Jacob from his harnesses, he cries “Why don’t you just burn him at the stake?” Louis transfers him from the hospital bed to a wheelchair and whisks him back to the safety of his office. “I was in hell,” Jacob murmurs. “I don’t want to die."

Louis cracks a knowing smile. “Eckhart saw hell, too,” he says, referring to the thirteenth century German Catholic theologian, philosopher and mystic. “The way he sees it, if you’re frightened of dying and you’re holding on, you’ll see devils tearing your life away. But if you’ve made your peace, the devils are really angels freeing you from the earth. It’s just a matter of how you look at it.”

Carl G. Jung — a Swiss psychiatrist whose ideas the filmmakers (and Jacob) are almost certainly aware of — writes in his 1964 essay Approaching the Unconscious that symbols point to something working deep in the human unconscious to conjure the vast, significant mysteries of existence. When signs, like an effigy or image of the human body, are imbued with mystery, they become symbols because they now stand for something beyond the object itself, though their true meaning remains elusive and subjective.

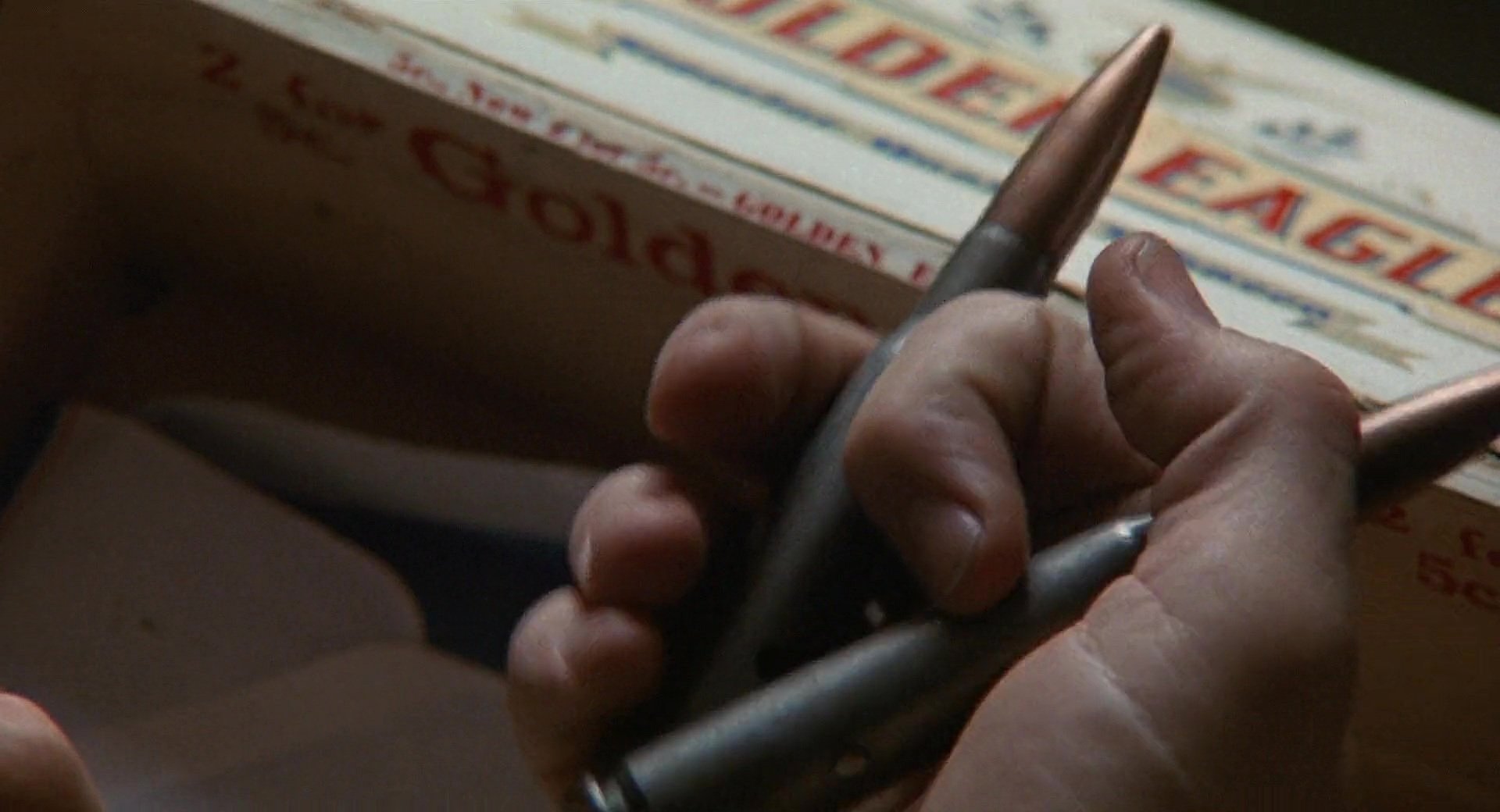

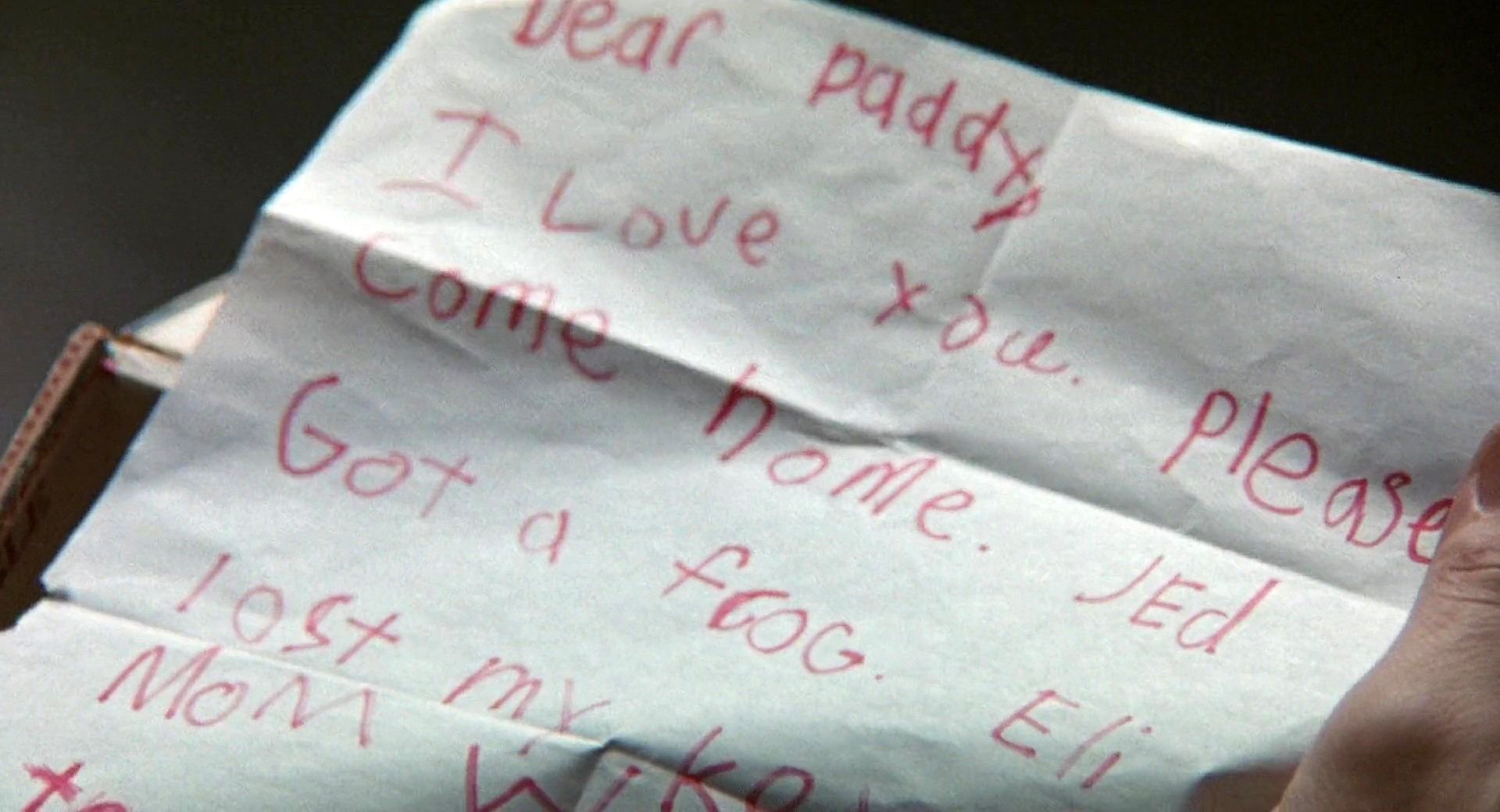

Back at the apartment, Jacob sorts through the contents of an old cigar box, a personal collection of sacred objects he's held on to over the years: honorable discharge papers, a Master of Arts degree from Brooklyn College, dogtags (the religious preference is Jewish) and a letter from Gabe.

In one of the film's most visually and thematically darkest scenes, Jacob meets with Michael (Matt Craven), a former chemist in the Army's "Ladder" program, who reveals the truth of what happened on the day Jacob's platoon was attacked: in a drug-induced craze, the soldiers turned against each other, their lives sacrificed on the altar of war.

Thus enlightened, Jacob gives a taxicab driver all the money in his pocket to take him "home," back to the apartment he once shared with Sarah. Rosary beads jangle on the dashboard as the cab cuts through the dense night fog like Charon on the River Styx.

A doorman at wrought iron gates welcomes Jacob as an old friend or St. Peter might. Past halls of white marble and crown molding, Jacob finds tableaus of unfinished homework and half-eaten dessert, a life in framed photographs on the piano.

Jacob sits on the couch in quiet contemplation as rain falls outside and a sharp blue light cuts into the room from a low angle. In a montage set to a slowly beating heart, the most significant memories of Jacob's life come flooding back in grainy 16mm.

The heartbeat stops. The rain has ended. Jacob awakens and finds Gabe sitting on the steps, bathed in heavenly morning light. The little boy takes his father by the hand and leads him upstairs, and the image dips to white.

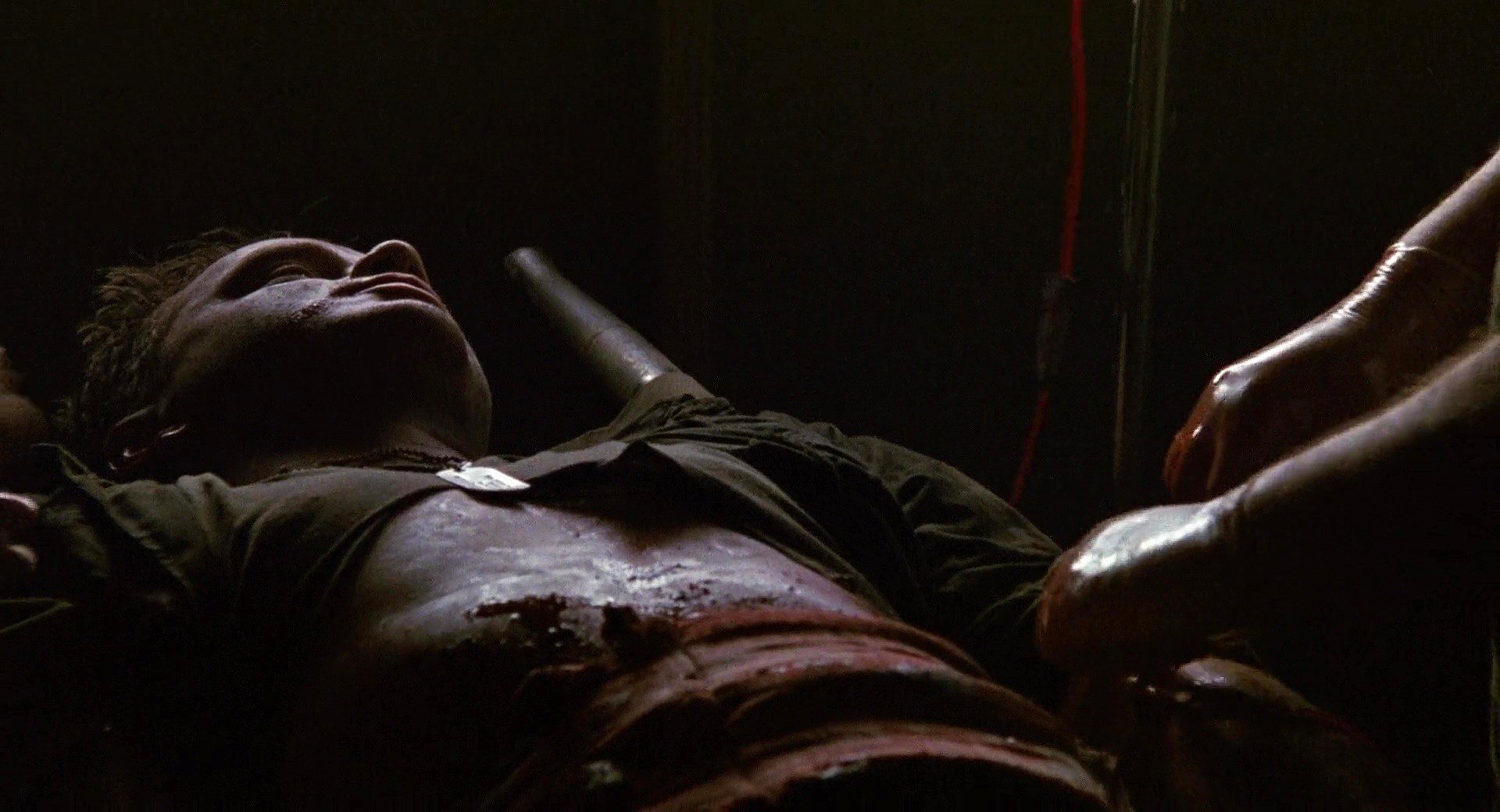

We are back in Vietnam. Having succumbed to his injuries, Jacob lies dead on a stretcher in a field hospital, his prone body still enough to have been carved from stone, with the faint hint of a smile upon his face. “He looks kind of peaceful,” says a medic as he removes one of Jacob’s dog tags.

Religion uses iconography to tell stories of life, death and redemption where traditional language is insufficient and personal experience with a system of belief isn't required. Symbols are necessarily universal as well as mysterious, and only when coupled with a text or image or transferred to a personal object or sign do they become specific. Jacob's Ladder inverts this formula by taking the universal experience of dying — in a narrative lifted from The Tibetan Book of the Dead — and using specific symbols to imbue it with a deeper, more personal meaning.

1.85:1

Panaflex G2, Eyemo, Arri II C

Panavision Super Speed primes; 25-250mm T4 Cooke/Panavision, 20-120mm T3 Angenieux/Panavision zooms

Kodak Color Negative

Processed by Technicolor New York

1990, Prod. Carolco Pictures/Distrib. TriStar Pictures