Photographing The French Connection

An exciting screen adventure, superbly photographed to capture wild action and the true grit of Fun City.

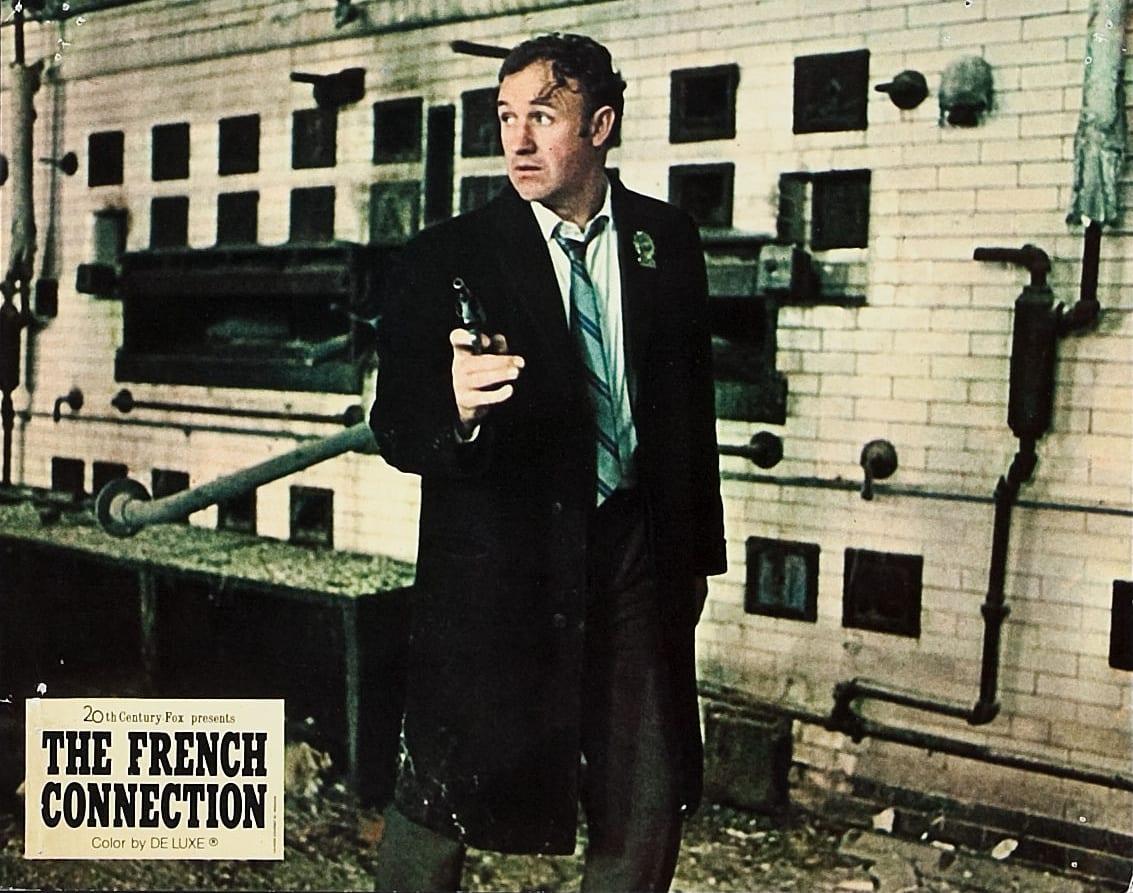

The French Connection, a Philip D'Antoni Production for 20th Century-Fox release, based on the bestselling book by Robin Moore, is a perfect example of the truism that reality is nearly always more dramatic and unpredictable than fiction.

The film depicts the exciting real-life story of a pair of dedicated, hard-working New York City Narcotics Squad detectives, Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso, who played a long-shot hunch that eventually led to the smashing of a $32,000,000 international dope smuggling ring. The trail proved a long and arduous one, and before it ended, it involved leading citizens of both France and the United States, including France's most popular television personality of the day.

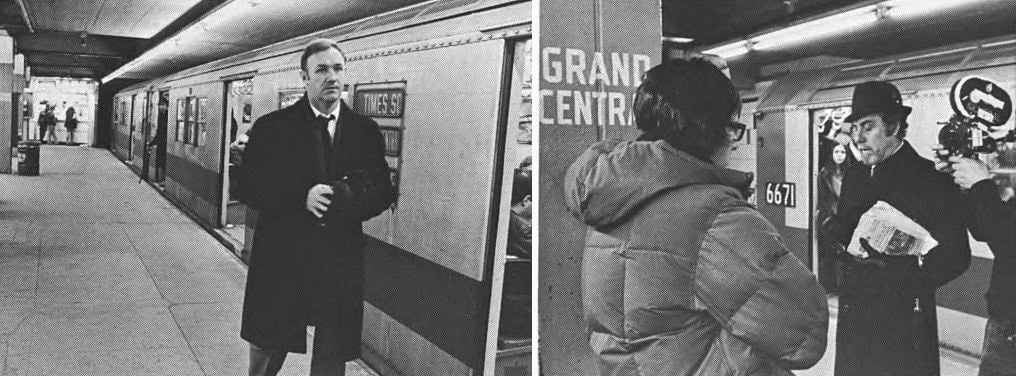

The French Connection marks one of the most ambitious movie projects ever to be filmed in New York City. Eighty-six separate locations throughout the city were utilized, covering Fun City scenically as it has rarely been covered before in a feature film. Locations included such Manhattan sites as the swank Westbury Hotel on Madison Avenue, Central Park, Park Avenue, the lower East Side, Little Italy, and the busy shuttle beneath Grand Central Station; the Bedford-Stuyvesant and Coney Island sections of Brooklyn, Hunt's Point in the Bronx, Maspeth in Queens; and Ward's Island, in the upper East River near Hell Gate. In addition to New York City locations, The French Connection also filmed at key government buildings in Washington, D.C., and in Marseilles, France.

Besides the almost overwhelming logistical problems involved in transporting cast and crew to the record number of filming sites (no formal studio interiors were utilized), producer D’Antoni was daily faced with the challenge of filming, mostly outdoors, during New York's highly unpredictable winter months of December through February.

“The winter was when the actual events occurred,” said D’Antoni, “and there was never any question that we would try to achieve a similar effect. Filming in New York in the winter presents unique problems to the filmmaker, juggling schedules and locations, cooperating with various city authorities, moving hundreds of people and heavy equipment all over town, often in snow and sleet, but it was worth it. We achieved a 'feel' of the streets impossible to duplicate on a Hollywood studio lot. And it had a subliminal effect on our actors, too. When Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider played numerous scenes in sub-freezing temperatures where they were supposed to be tired and cold while trailing their quarry, they were tired and cold. This overall sense of reality communicates itself to today's perceptive audiences, who often absorb a film's authenticity rather than see it.”

One of the highlights of The French Connection is a pulsating, mile-a-minute "chase” sequence through the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn. "This isn't a 'chase' in the ordinary movie sense,” noted D’Antoni. "What we have, in visual terms, is a detective (Hackman) in a commandeered car chasing a killer (Marcel Bozzuffi) trying to escape on a moving elevated subway train. Hackman has to drive with one eye on the traffic, the other on his quarry. We constantly cut between both individuals, showing the interaction as the detective pursues and the criminal flees. Of course, there's some violence in the dramatic action of the sequence, but it flows naturally from the scene. We hope audiences will react viscerally to the mounting excitement, much the same way they did to the now-classic chase sequence in Bullitt.

Producer Philip D'Antoni has a personal interest in the subject of The French Connection far beyond his professional dedication to the film. He is a native New Yorker, with a passionate love for his hometown and a terrible sadness at what time, crime, and particularly, the new drug culture, has done to degrade what he still believes is the finest city in the world.

“Some people believe that New York is a terminal case,” says D'Antoni, a graduate of Fordham University, who began his career in the CBS mailroom. “I don't buy that pessimism at all. I think we can solve all our problems, if we take them in stride and deal honestly with them. And that includes drugs. Obviously, you've got to reach the big 'pushers,' the masterminds behind the operation. If you cut off the big guys, if you make it too tough for them to operate, you are well on your way to licking the problem in New York and in the whole country for that matter. That's what Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso did in The French Connection. The amount of pure heroin confiscated at the end of that investigation is still a record haul for law enforcement authorities in the United States, with a street value of $32,000,000. I like to think that in our own modest way this dramatization of The French Connection will play a significant role in creating public awareness of one key aspect of a serious problem facing all of us.”

D'Antoni selected one of the industry's foremost young directors, William Friedkin, to helm The French Connection. A native Chicagoan, a city not unfamiliar with the drug problem, Friedkin shares his producer's passion for filming The French Connection" so that it deals truly with its subject.

Says Friedkin, "This is a dirty, stark and ruthless story, fortunately, larded with some humor in certain incidents. It had to be captured that way on film. The main characters, be they cops or criminals, project their own complex inner reality. You know, some are actually walking zombies and monsters, and I don't mean just the so-called 'bad guys.' Of course, Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider carry the load, portraying two real-life human beings, heroic after their own fashion, who happen to be policemen. But we tried to film it honestly and with compassion, and I think we have not only an entertaining motion picture, but one which also makes a contribution to understanding the nature of ourselves."

Rarely has a feature film depended so heavily upon photography for its dramatic impact as did The French Connection. The gritty, gutsy visual style of this picture is, perhaps, more important than any other single production element in establishing an authentic atmosphere, creating mood, building pace, and enhancing the force of the slam-bang action.

Selected for the important function of director of photography was dynamic, New York-based cinematographer Owen Roizman who, in the following interview, comments in detail upon the unique problems, technical challenges and cinematic techniques involved in photographing The French Connection entirely on location in the streets and structures of New York.

American Cinematographer: Although the photography of The French Connection is, as such, skillfully unobtrusive, it has a very distinctive visual style. Can you tell me how, in concept, that was arrived at and what technical approaches you decided to use in order to achieve the desired style?

Owen Roizman: In the first meeting that I had with Phil D'Antoni and Bill Friedkin, they told me that the one thing they did not want was a "pretty" picture. They wanted it to be rough, almost documentary, but with the look of a professional job to it. It had to be the kind of picture that would involve the audience. This meant that there would be a lot of hand-held camerawork, and they didn't especially care if the audience was aware of the camera. Another important goal was to not make New York look pretty. So the approach in scouting locations was to pick places that would make the city look the way it really looks. I tried to figure out some sort of a style that would carry that effect through — not necessarily to be different — but something that would add to the atmospheric result. I wanted the images to have a dismal, dreary look. We were going to shoot in winter and it was going to be cold. The feeling of those conditions had to come through on the film.

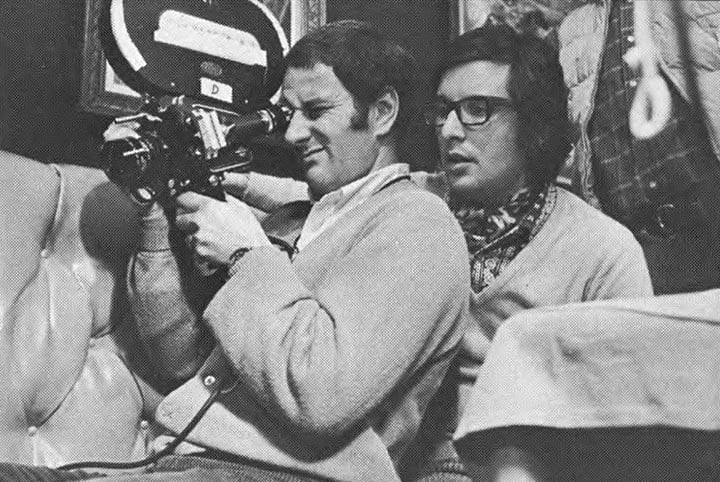

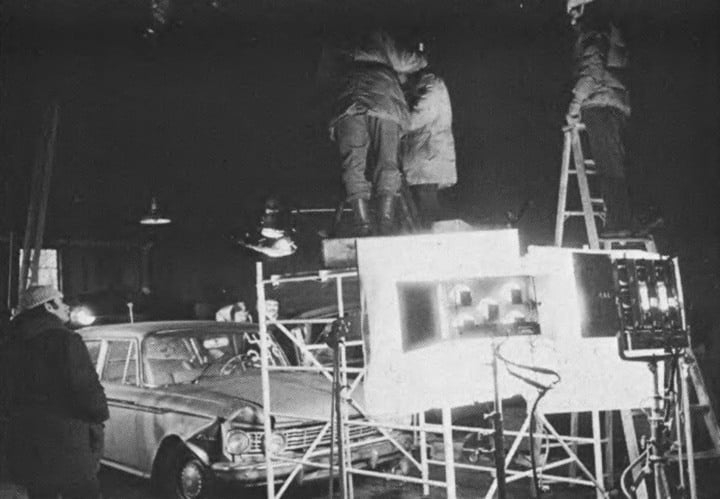

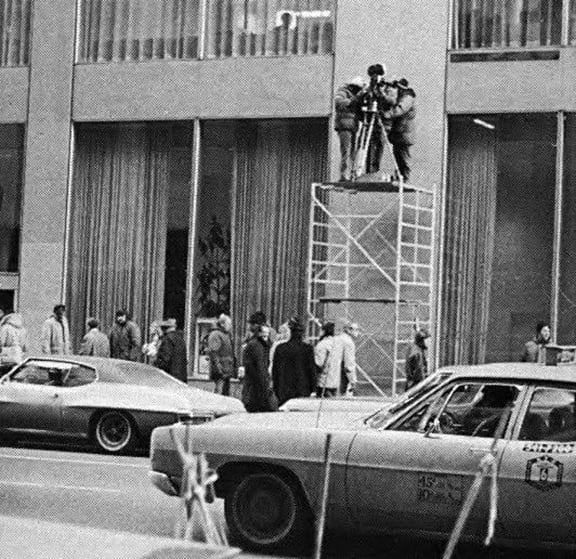

lines up a scene with hand-held Arriflex while Friedkin looks on.

In terms of mechanics, how did you set about achieving this?

Fortunately, the quality of light that is characteristic of winter in New York lends itself to the type of photography I had in mind, but it called for a complete reversal of the technique I would use in shooting a "sunny" subject. When I'm working with contrasty sunlight, I take the approach of overexposing the film and printing it down in order to get a very rich kind of color. In this case, I did just the opposite — underexposing everything and printing it up. This flattened the contrast out and got a bit of grey into it.

By how much, in general, would you say that you underexposed it?

It varied somewhat according to the particular scene, of course, but all of the night stuff was underexposed by a full stop. I also force-developed everything one stop and then underexposed on top of that.

Does that mean that you might be two stops under when you shot the scene and then pushed it one stop in development?

Yes, that's generally what I did for the night work. For the day stuff, I usually underexposed it a stop and a half, force-developed it one-stop, and printed it up from there. I tried to shoot it so that the lab could do very little to change it. I knew that if I gave the lab a solid, normally exposed negative and then asked them to print it in a special way, it just wouldn't have the same look. They would be very creative and make a very beautiful print of something I didn't want to look beautiful at all. I tried to give them a very thin negative so that they would have no leeway in printing it.

Gordon Willis does that, too.

Yes, I know. Gordie and I are old friends. We were assistant cameramen together. Another thing we decided upon was to never go for any fancy compositions. We would set up the shots very simply and shoot them. We never went for foreground objects or out-of-focus things. It was a matter of staging the action and shooting it with the best lens possible. We never used wide-angle lenses or long lenses just arbitrarily. If we used a long lens, there was always a reason for it. We didn't use it a lot, but I feel that every shot we made with a long lens was in the picture because we carefully chose when to use it — and when not to. We never made any distorted wide-angle shots, either. You might say that the photography, from the standpoint of composition, was very simple and straightforward.

What about your approach to lighting The French Connection?

Ordinarily, for this type of film, I might take the "light and shadow" approach — nice crisp sidelight with black shadows. That would be my normal style, but, in this case, I didn't want to follow what I would do normally. Instead, I used more fill light than I normally would. I underexposed the key light one-stop but filled it in a lot. That's what flattened it out.

On the screen, just about everything in the picture has the feeling of having been shot with available light.

That's the effect I worked for throughout the picture, that feeling of available light — but it wasn't. I can tell you the times I used available light and it wasn't very often. I didn't light any exterior day scene — that was all available light. If there were any interior car scenes, these would naturally have to be lighted. But anything that was out on the street in daylight was shot without fill light. I feel in general that if fill light isn't necessary, it shouldn't be used. It wasn't necessary in our street scenes, so we didn't use it. Also, we didn't really have the time to set fill light and we were able to move much faster without it.

In this picture, at least, you didn't have to glamorize anything.

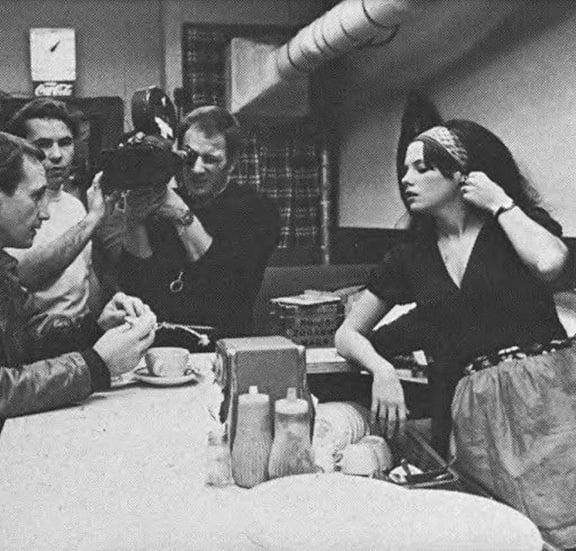

Which was like a breath of fresh air. We didn't have to worry about making anything look pretty. The approach to interior lighting was to underexpose, working at very, very low light levels and using small units. Most of the places were lighted with Dinky-inkies. In the nightclub sequence, for example, 90 percent of the lights were inkies. The interesting problem there was lighting the people at the tables. The ceilings were very low and there were mirrors on two walls. We had to do a hand-held walking shot through the whole club, so it was difficult to hide lights. I had to figure a way to light the people at the tables and it was done by taking an inky bulb in a socket, wrapping a piece of spun glass around it and then a red gel. These lights were set right on the tables and were all hooked into one master dimmer that took them down to between four and six foot-candles — which was all that I needed. As you know, when you photograph red, it's very difficult to overexpose it — almost impossible — so I wasn't worried that the lamps would look overexposed. As it turned out, they looked normal and most people think they are the lights normally used on the tables. They were our own lights, however, and that's all that was used to light the tables-nothing else. There wasn't any room for anything else.

Would you consider that to be your most difficult lighting problem?

It was the toughest lighting job on the picture, but we knew that going in. There were problems with fluorescent lights in some of the interiors. Take that sequence shot in Grand Central Station, for example, the one I call the cat-with-the-mouse chase, where they jump back and forth on and off the subway train. To light that area and make all the set-ups we had to make, with all the extras we had to use, would have taken forever — and we just didn't have forever to do anything. Everything was on a very, very tight schedule. So I decided to shoot without any lights at all, using only available light, and I didn't use any photographic lights at all.

Was there enough light available?

It didn't look bright to the eye, but as it turned out, I had more light available down there than I had in any of the interior locations where I used my own lighting. In fact, I had about two to four times as much.

It appeared that you had rather cold light down there. Did you make any attempt to correct color temperature in the camera or did you leave that to the lab?

I left it to the lab, in this case. The big problem was that the fluorescents on the platform were a different color from those on the train, which were warmer. At first, I toyed with the idea of changing all the lamps in the subway cars, since there were only two or three cars to worry about, and then they would have matched the lamps on the platform. The lab could have made an overall correction and everything would have looked right and perfect. I did just the opposite. I let it go as it was so that part of it looked a little blue and the rest looked a little warm. I think it looked more realistic that way, and it saved all the time that would have been needed to change the lamps.

lamps lighting platforms were colder than those on train cars, but Roizman decided against

replacing them, in the interest of realism and speed of filming. Right: Many of the shots in the subway sequence were photographed with hand-held Arriflex.

What about lighting the scenes on the elevated train during the chase sequence?

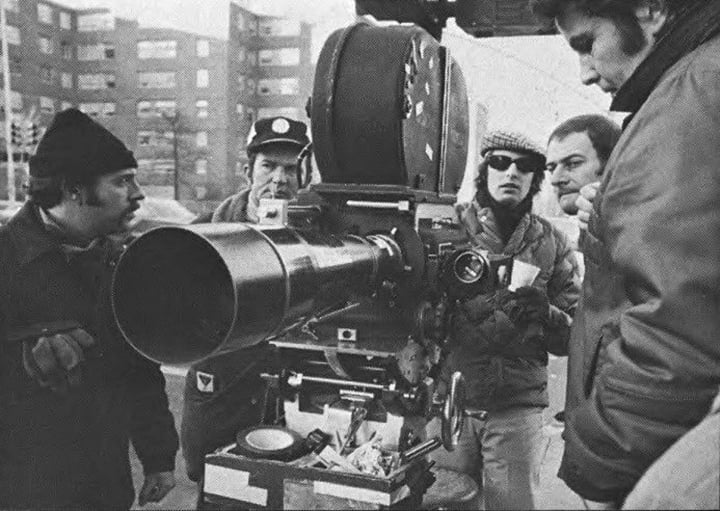

Those scenes would have been impossible to light, so I didn't use any extra lighting on them. We just shot with a hand-held camera — no tripod, no dolly. The biggest problem there was trying to match because the light was changing constantly. As we'd run along the track another train would pass and block out the light. Or we'd go between tall buildings and that would cut down the light in the middle of a scene. This made it a little difficult, a little tricky. But after a while, we got the feel of it and were able to do it with no problem. I had a terrific operator and my assistants were great.

Was the chase sequence filmed by the first unit or the second unit?

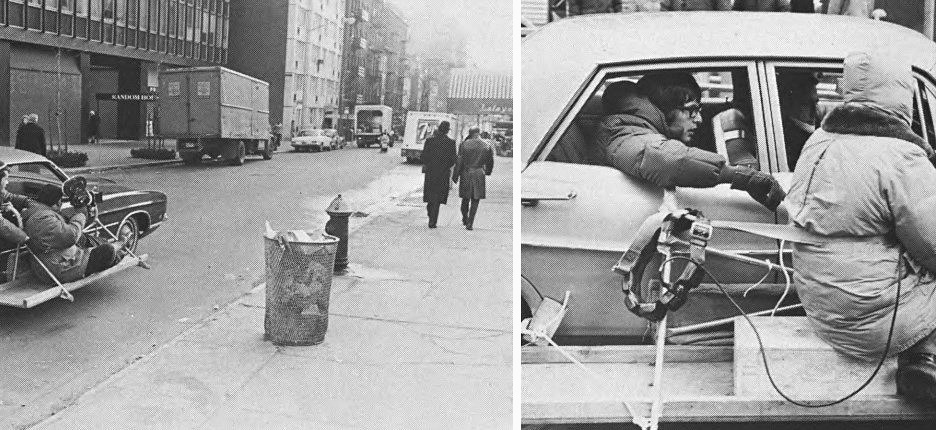

We filmed about 90 percent of it with the first unit. The second unit shot some running scenes on the ground, a few pass-bys, and inserts of hands and feet. We decided to use as much hand-held camera work as possible. We never made an actual dolly shot on the streets. Every time we had to make a moving shot, we'd do it out of a wheelchair or out the window of a car, moving along or walking. We shot with an un-blimped Arriflex a good deal of the time and we really didn't have a big problem with the sound. I don't know how Chris Newman did it, but he did it. He has a way.

Did they have to loop much of the sound?

They didn't have to loop anything, that I know of. Getting sound while shooting underneath the elevated tracks was really brutal because the trains were so noisy. I didn't think he'd get a track at all. I was amazed the next day when I went into the screening room and heard the sound. It was unbelievable.

Can you tell me about the various types of lighting units you used during the filming?

We used almost every type of light there is, including quartz lights. We tried to use small units wherever we could — inkies and things like that. But mostly we used a new lightweight softlight that is very compact. They call it a "Zip Light'' and it was made by a gaffer in New York. It's a 2,000-watt softlight made of aluminum, but it's about half the size of a regular 2,000- watt softlight. I adapted these lights with nets and various gags for hanging them simply in places where we'd never be able to hang lights of normal size. We never had to worry about ruining any structures. They put out a tremendous amount of light and cover a wide area — so I used them a lot.

Did you use any Brute arcs on The French Connection?

I didn't carry a Brute during the entire picture. I can see the use of Brutes sometimes, but not on this type of film. There was no necessity for using them. In general, I don't like to use them and I do so reluctantly. When possible, I like to avoid them — but they're a great protection in certain instances.

What about your night exteriors? You had some pretty wide expanses to light, didn't you?

We had one that was really big — that sequence with the Puerto Rican raid. It encompassed about three blocks, plus part of FDR Drive. But there were no Brutes involved. I used maybe four 10Ks for the main lighting — at the most. The rest were small units hung on fire escapes and on the tops of light poles, spread out all over the place. Instead of lighting it up brightly and going for contrast, I lit it sparsely and underexposed to give it a dingy feeling. I did that with all of the night stuff. There was one scene where the FBI agent and his partner drive up and offer Gene Hackman a drink from a bottle. That was lighted entirely with inkies — about six to eight foot candles. I like to shoot wide open on everything. I always do it. Some people criticize me for it — especially my assistants. It's rough on them — I know it and they know it — but the ones who have worked with me on a few pictures know that I'm going to do this and they're used to it by now.

When you say "wide open," just how wide do you mean?

Whatever is the maximum aperture of the lens I'm using.

Is there a reason?

I like to maintain a shallow depth of field. Whatever I'm focused on — that's what I want to be sharp. Even with a wide-angle lens, everything but the main subject will be just slightly soft. It won't be as crisp as the center of attention. Every time I stop the lens down it disturbs me. If I have to shoot a scene at f/4 or f/5.6, it bothers me, so I always try to shoot wide open.

It also makes it possible for you to shoot at extremely low light levels, doesn't it?

Yes. The main reason I tike to shoot at such low light levels is that I don't have to use much fill light. When you work at low levels like that, the light has a tendency to fill itself in. The ambient light picks up in the shadows. In fact, if you turn a fill light on, it washes everything out. With a high light level, you get the opposite effect. The scene picks up contrast. On The French Connection, the highest I ever worked in a controlled situation was 32 foot-candles — which will give you f/2.3 if you force-develop one stop. I avoided using the zoom lens as much as possible because it's slow and requires more light.

You had a great many location interiors on this picture. Can you tell me about some of the more challenging ones?

The one that was the most challenging was the raid on the bar. The ceiling was very low and we had to contend with some daylight coming in the windows. Bill Friedkin and I talked about the sequence in detail ahead of time. He laid out the action and showed me exactly how many setups he wanted to make in the two days that were scheduled. It was a lot of setups for the size of the room and the amount of people involved, so I tried to figure out a way to do it without having to change lights for every setup. I built a row of lights onto the ceiling and used photoflood bulbs, all on a master dimmer. There were fluorescent lights on the walls and I used them just as they were, keeping the photofloods low so that they would blend in with the fluorescents and not overpower them. There were also some practical lights on the ceiling. I used ordinary 100-watt bulbs in them and took the photofloods down to about the same intensity. The only other units were a few Dinky-inkies used for kick lights or to open up really dark areas.

What about the scenes where the detective throws the informer into the men's room?

That's the most interesting sequence I've ever shot. I had asked Bill Friedkin what he would like to see in there, what kind of feeling he wanted, and he said: "Whatever you'd actually see — that's what I'd like to see." There was a bulb in an overhead socket, and that's all that was lighting the men's room. So I just took that bulb out and replaced it with a photoflood, and that's the way we shot it. I even stopped down a little bit, because I didn't want it to be too bright. When we went to shoot the scene, Friedkin chickened out a little bit and asked if I wasn't going to use a little fill light on the black actor [Al Fann, playing an undercover cop]. I felt that you could see the actor well enough to tell who he was, and that was enough. But just to appease Bill, I put some white cards on the floor to bounce the light from the one photoflood. They didn't do much, but he felt better. Anyway, I kept it 90 percent the way I wanted it and I loved the whole sequence. It was printed down a little bit in the final print. I wasn't around when it was timed — but Friedkin printed it down.

Can you think of any other interior sequences that posed special problems?

Yes, that sequence where the dope smugglers are eating inside the restaurant and Doyle is standing on the sidewalk across the street eating a slice of pizza. It was very challenging because we had to start on the smugglers inside and then zoom through the window to a close shot of Doyle. I knew that if we put gels on the windows, the image wouldn't be sharp enough when we made the zoom. It would be too diffused. So I had to light up the interior of the restaurant to balance with the exterior and use an 85 filter over the lens. But I also wanted to use a very warm lighting inside the restaurant. In order to really be able to tell what I was going to get, it would have meant using blue lights inside and then adding some kind of warm gel. However, the light loss would have been so great that it just didn't make sense. So, instead, I used 3200K lights in there and added a slightly warm gel. I wanted it to look quite warm inside so that the outside would look even colder than it actually was.

What about the problems of shooting that last sequence, where the action takes place in what appears to be an abandoned warehouse?

When I first saw that location I loved it. My main problem was how to make it look like it wasn't lighted, even though it had to be. I really had to think about that one. I finally decided to cover all of the windows with tracing paper, light everything from outside and let it flare out. When you take that approach, it can be very tricky, but I had used it in shooting commercials and I knew what I could get away with. I did no lighting inside the place at all, except for a few tight closeups. Then I simply recreated the effect with a FAY light and some tracing paper. As it happened, there was a terrible snowstorm raging outside on the day we shot it, and it was hard on the guys who had to run around in the snow setting lights outside about 15 windows.

How did you break down the photography of the shoot-out at the end of the picture?

The director decided where the cops and the bad guys were going to be. Then my operator, Enrique Bravo, took one camera and I took another one. Friedkin just had them shoot it out with nothing planned and we covered it in documentary newsreel style. We just did whatever we wanted and tried to outdo each other to see who could get the best shots. We had a lot of fun shooting it.

Under what conditions do you think the hand-held camera should be used or shouldn't be used?

My theory about photography is that you should use whatever is necessary to make the particular shot. There are some operators who can make hand-held shots so smoothly that they don't look hand-held. The audience never becomes aware of it. In The French Connection, we wanted it to look rough. In fact, we hid Enrique [Bravo]'s shoulder brace so that the hand-held shots wouldn't look too smooth. After a while, he got to like it so much that he wanted to shoot everything hand-held. Instead of taking time to set up a dolly, we'd simply put him in a wheelchair with the camera. If the road or sidewalk or whatever was fairly smooth, it worked very well and saved a lot of time. There were other sequences, like the one where they were testing the heroin, in which the camera was locked down solid. The audience was not to be made aware that the camera was involved at all.

There were a couple of sequences in which you departed from the rough, dingy style used in most of the picture. Can you tell me about those?

Yes. There were two sequences which we decided in advance should not be dingy. One was the heroin-testing sequence. The other was the sequence that took place inside the apartment of the wealthy guy who was supposed to be the contact man. These represented a complete contrast in technique. The scene with the contact man was shot in a suite in the Hotel Pierre and we wanted that to have a rich look. I overexposed everything so that when it was printed down it became much richer. The walls and ceilings of the room were white, so I put photofloods in the practical lamps and bounced a couple of lights off the ceiling. That's all the lighting that was used.

look.

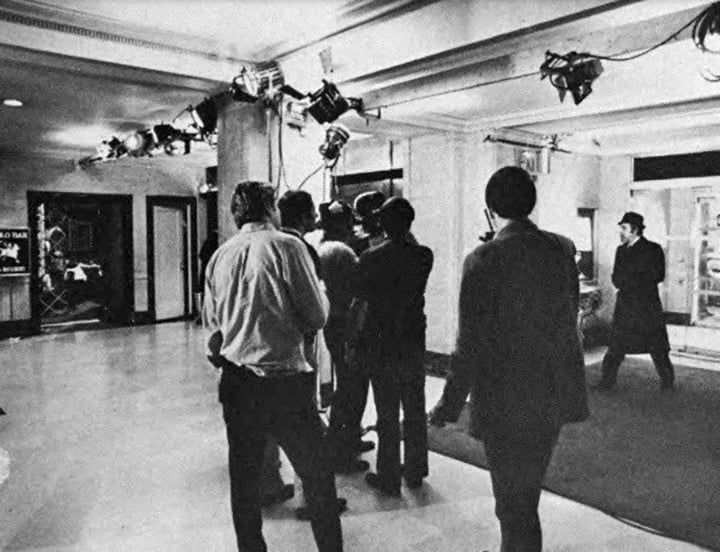

The sequence inside the lobby of the Westbury Hotel had the available light look, but it actually must have required quite a bit of lighting. Isn't that so?

Yes. It was actually illuminated with quite a bit of our lighting. It was a pretty big place. So the crew took an early call to come in and rig it. We tried to pre-rig the locations whenever possible in order to save time. I'd line out what I wanted in a certain location and the crew would go ahead and hang some lights and lay the cables. Then we'd come in just before shooting and do the actual lighting. This saved a tremendous amount of time.

What can you tell me about the shooting of the chase sequence?

As exciting as the chase was, it really provides very little to talk about. The approach we took was very simple. The sequence was broken down into about five stunts, with the second unit doing some isolated shots. For each shot inside the car there were two and sometimes three cameras rigged. These gave us over-shoulder and point-of-view shots and closeups of Hackman, who did a lot of the driving himself. The crashes were shot from outside using four or five cameras — all with different lenses and from different angles.

Did you undercrank much of the chase footage?

I undercranked at 20 frames and sometimes 18, but never less than that because they were driving very fast. The biggest chore was controlling traffic — blocking off streets for six or seven blocks. There was one real accident in the chase — when our car crashed into a white car and spun it around. That wasn't staged. One of the stunt drivers simply missed his mark.

What about lighting inside the car?

I tried to avoid it, but there were a couple of shots where we needed a bit of fill, so we used a Sun-Gun — the biggest one they've got. It didn't put out much light, but it was enough to keep Hackman's face from being a silhouette. There was one great tie-in shot where the operator started on Hackman's face and panned up so that you could see the train racing along. I loved that shot.

What special problems did you have in shooting the scene with all those people on the streets of Manhattan?

That was the triangular surveillance sequence shot on Madison Avenue. We decided to shoot it without extras, as we did on all of the exteriors. The assistant director was worried about people looking at the camera, so we talked about hiding the camera, camouflaging it, or shooting out of cars. The day we went out to shoot, I said to him: "Let's try to shoot without any coverup. Let's just put the camera out on the street, hand-held or on a tripod, and see what happens." I had the feeling that New Yorkers were so used to seeing newsreel cameramen running around that they would pay no attention. Sure enough—it worked! We even got so brazen as to set up a 12-foot parallel right on the sidewalk in the busiest section of Madison Avenue — and nobody looked at the camera.

Roizman earned an Academy Award nomination for his outstanding cinematography in the film, which was later hailed by the ASC as among the most memorable and influential camerawork of the 20th Century.

Here, Roizman looks back on shooting the film:

The French Connection earned seven other Oscar nominations as well, winning for Best Picture, Best Actor, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Editing and Best Director.

Roizman and Friedkin would soon re-team to photograph The Exorcist.

The cinematographer was celebrated with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 1997 and presented with an Honorary Oscar in 2017.

AC Archive subscribers can access this entire issue, as well as more than 1,200 others. Subscribe here.