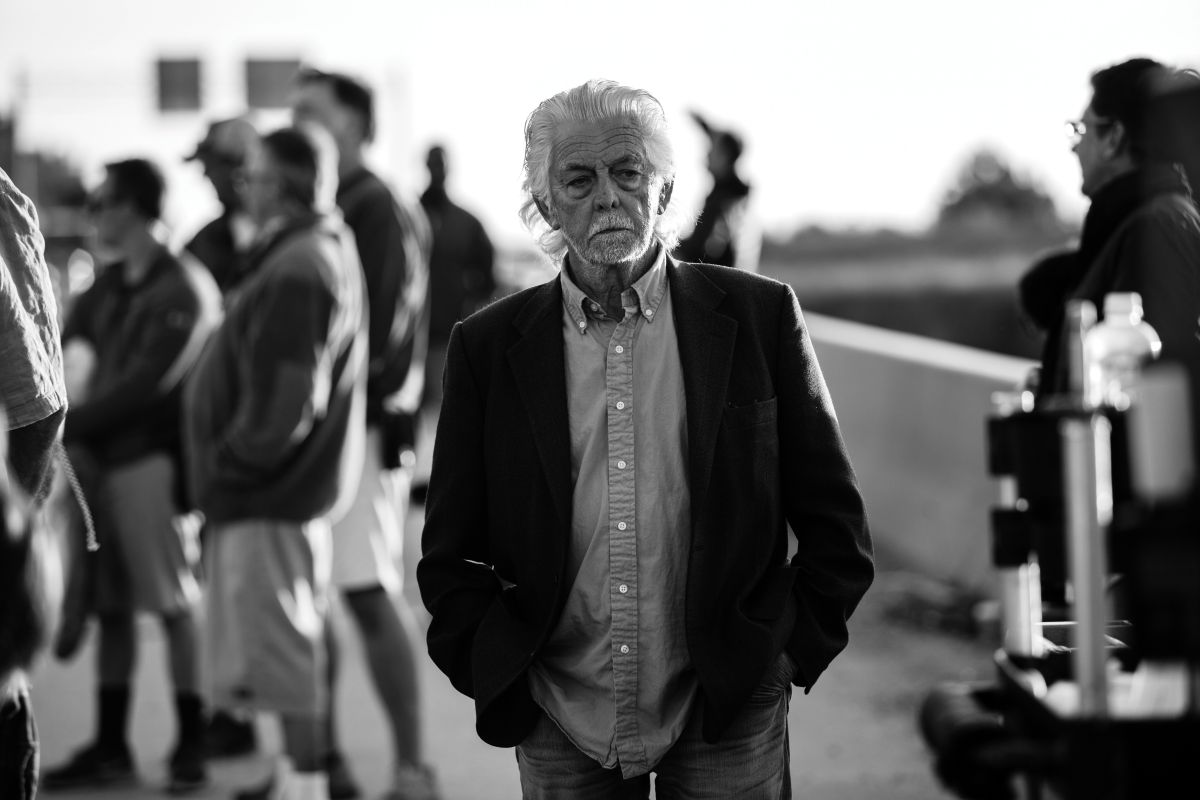

Rock Tours — Anthony B. Richmond, ASC, BSC Looks Back at His Career

Anthony Richmond, ASC, BSC looks back at his career — and his collaborations on projects featuring some of the world’s most iconic musicians.

Additional reporting by Iain Marcks

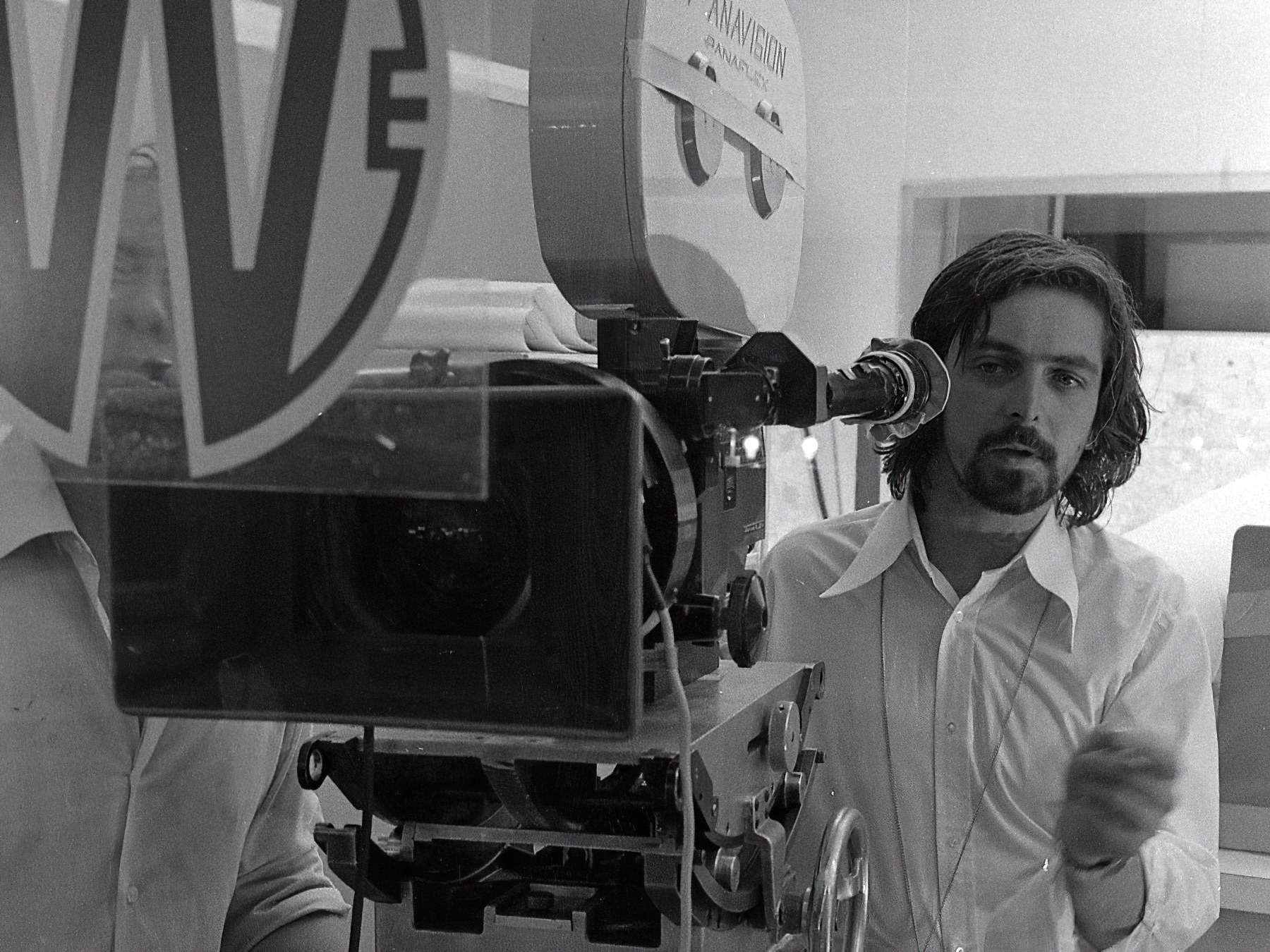

Anthony B. Richmond, ASC, BSC’s oeuvre includes more than 85 film and television projects and suggests a cinematographer as diverse in genre as he is prolific. He began his career as a 2nd AC on such landmark films as From Russia With Love and Doctor Zhivago, became a full-fledged cinematographer at the age of 25, and has excelled in the occupation for more than 50 years.

Cinematographer-turned-director Nicolas Roeg tapped Richmond to shoot several features, including the horror classic Don’t Look Now (for which Richmond won a BAFTA) and the psychological drama Bad Timing: A Sensual Obsession. A sampling of Richmond’s other credits includes the comedy Legally Blonde, the cult-classic horror film Candyman (1992), the comedic Western Sunset, the sports comedy The Sandlot, and the well-regarded telefilms Heart of Darkness and Bastard Out of Carolina.

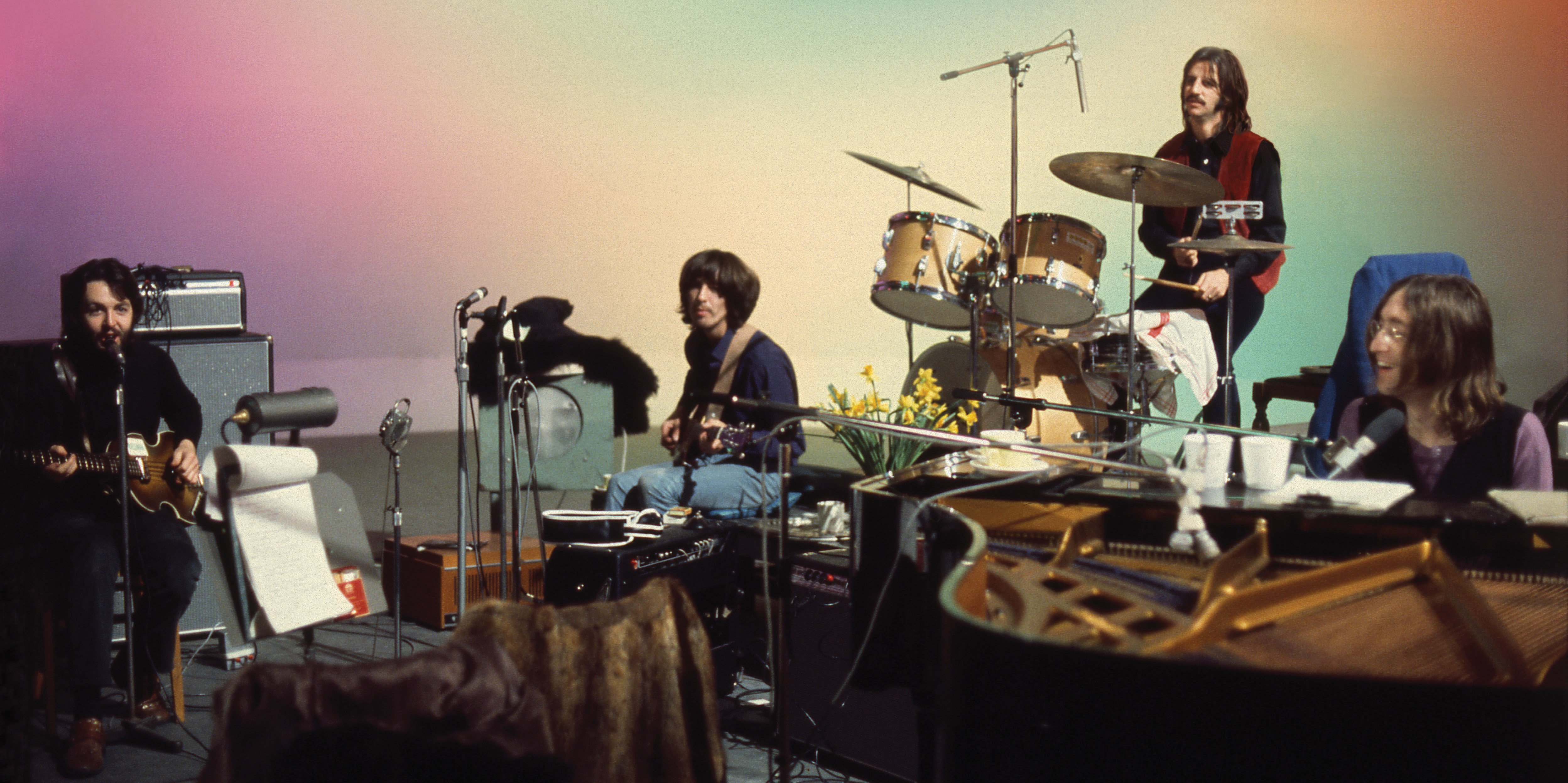

He has also filmed some of the music world’s most enduring icons, including the Rolling Stones (The Rolling Stones: Sympathy for the Devil [aka One Plus One] and The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus) and David Bowie (The Man Who Fell to Earth). His work on the 1970 Beatles documentary Let It Be offered a look into the legendary rock band as they labored toward their difficult breakup. It would be the last Beatles film for 51 years, until Disney Plus began streaming Peter Jackson’s 2021 critically acclaimed docuseries The Beatles: Get Back, which draws from 56 hours of digitally restored footage Richmond shot for Let It Be, most of it previously unreleased.

“[I] never thought of [the Beatles] as stars. I saw them as guys in a band. To me, stars were movie stars.”

— Anthony B. Richmond, ASC, BSC

Looking back at the weeks he spent filming the Fab Four with director Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Richmond says he “never thought of [the Beatles] as stars. I saw them as guys in a band. To me, stars were movie stars.” And whereas Jackson’s series dwells more on moments of inspired camaraderie than the acrimony highlighted in Let It Be, Richmond says Lindsay-Hogg’s film jibes with his own recollections. “Let It Be was a really dark piece about the Beatles breaking up,” he says. The cinematographer remembers a lot of infighting and tension, “but it certainly wasn’t an unpleasant experience for me. It’s always fun shooting. We had no contract; we were paid by the week.

“Denis O’Dell, a producer on the project, had decided to document the band as they created an album and planned a live performance. He called me and said, ‘Listen, the boys are down at Twickenham Studios. They’re going to rehearse this spectacle they’re planning. Why don’t you get a couple of film cameras and a couple of guys and come down?’ So I got two Arri BLs and took [camera operator] Les Parrott and [2nd assistant camera] Paul Bond to the studio, and we started shooting. We used Arriflex/Zeiss Vario-Sonnar 10-100mm [T3.1] zoom lenses. One camera was on a tripod and I handheld the other.”

The band was not pleased with Twickenham as a creative space, and neither was Richmond. “It was very boring — a big, old stage with a huge white cyc. There were a lot of lights rigged up in the gantry, so I had gaffer Jim Powell introduce different gel colors onto the cyc every day to get rid of the horribleness of the white.”

Richmond developed an easy rapport with the band. “They were very accessible. When we weren’t shooting or rehearsing, we’d sit and talk, read the paper, drink tea.” Tensions among Paul McCartney, John Lennon and George Harrison were heating up, “but none of it ever spilled over onto me.”

Harrison all but quit the band until the sessions were relocated to their basement recording studio at Apple Corps on Savile Row. The change of scene and impromptu collaboration with keyboardist Billy Preston injected new life into the proceedings. Meanwhile, Richmond and his crew continued filming in the more intimate environment. “It was a tiny recording studio,” Richmond recalls, “but they had all the good gear there, and they had Glyn Johns, the engineer.”

The filmmakers shot every day as the Beatles worked on their songs and lobbed ideas back and forth about the upcoming performance. “They talked about doing a free concert in Hyde Park, at the Colosseum in Rome, and even on an ocean liner,” Richmond recalls. “One day, Lennon asked me what our footage looked like. I told him it was pretty good, and he wanted to see it. I printed about 20 minutes of it and showed it to them in the theater at Twickenham. They liked it, so Michael decided we’d use the footage [itself] as the film. We just needed a way to end it.”

What they decided upon was the now-famous unannounced concert on the rooftop of their Apple Corps headquarters — the Beatles’ last live performance.

Once the band settled on the rooftop show, a structural engineer was brought in to ensure that the roof would support a live rock concert.

Richmond deployed Arri 16mm cameras throughout the area: five on the roof with the musicians, four on surrounding rooftops (some equipped with long lenses), and three on the street below capturing the reactions of passers-by. “I was operating a very big camera with a 1,000' mag right in front of Lennon, looking up at him,” Richmond recalls. “We didn’t have much of a vision at that point. There were no rehearsals, and there was no video tap, so Michael wasn’t going to see anything until it was printed. We just shot whatever we were given by the band.”

“The police listened for a while and then had [road manager] Mal Evans literally pull the plug on the amps. [George Harrison plugged them back in and] the boys just kept playing!”

Anticipating a visit from the local constabulary, the production built a small, box-like enclosure with one-way mirrors in the building’s lobby. Camera operator Mike Fox was concealed inside with a 16mm camera. As expected, two police officers came knocking, intent on finding the source of the public disturbance. Get Back shows Fox’s footage of road manager Mal Evans trying to hold them off. When they were finally admitted, Fox followed them up to the roof with his camera. “The police listened for a while and then had Mal literally pull the plug on the amps,” says Richmond. Harrison plugged them back in, and “the boys just kept playing! One of the officers asked who was in charge, and everybody pointed to Michael Lindsay-Hogg. So they said to him, ‘If you don’t stop this now, we’re going to arrest you.’ And we stopped it!

“Michael is a great friend of mine to this day, but that always infuriated me because I thought it would’ve made a wonderful ending if he’d been arrested and led away,” he says with a laugh. “What would they really do to him?”

Richmond had worked with Lindsay-Hogg previously, when the director was sent along to help Richmond shoot the title sequence for Basil Dearden’s Only When I Larf, the cinematographer’s first feature. “Normally the title company would shoot that, but as we were using the actors, they wanted me to do it,” Richmond says. “When we were done, we went for a drink, and Michael said, ‘What are you doing next weekend? Why don’t you come and shoot something with the Rolling Stones that I’m directing?’ That’s how it all started.”

The result was a short video of the band performing “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” for Ready Steady Go!, a weekly series Lindsay-Hogg directed. “Groups would usually play live on the show, but the Stones didn’t want to do that anymore,” says Richmond. “We used one camera to shoot them performing on a small commercial stage.”

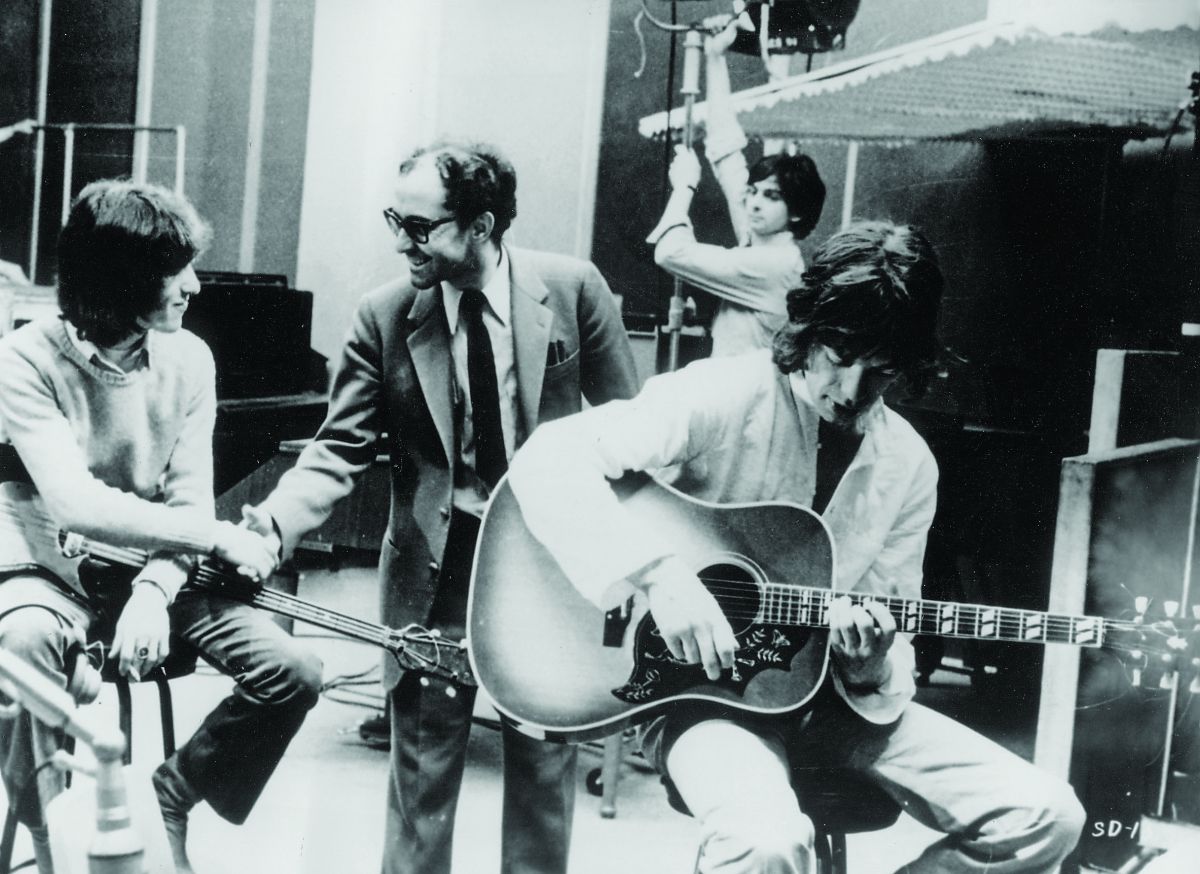

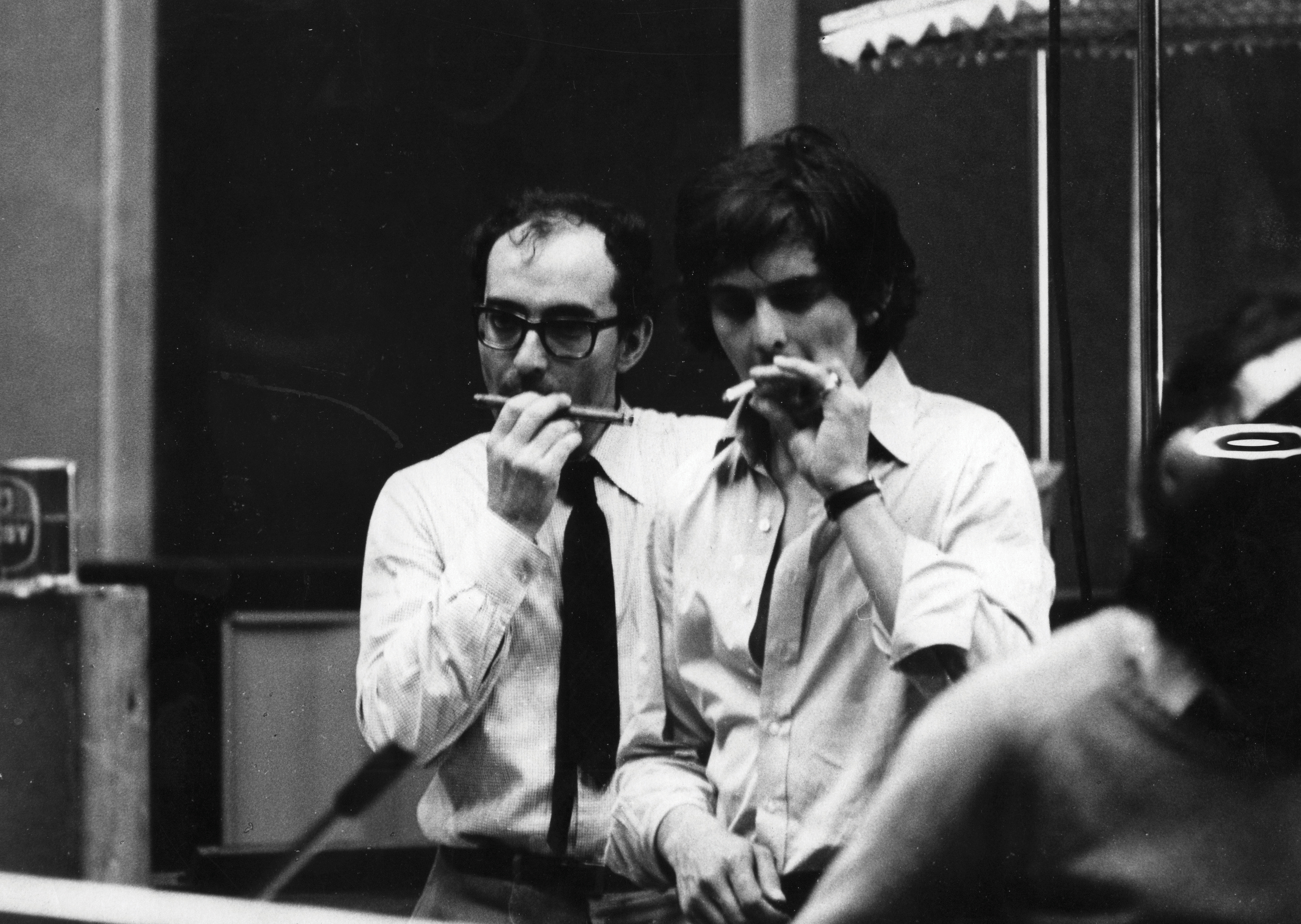

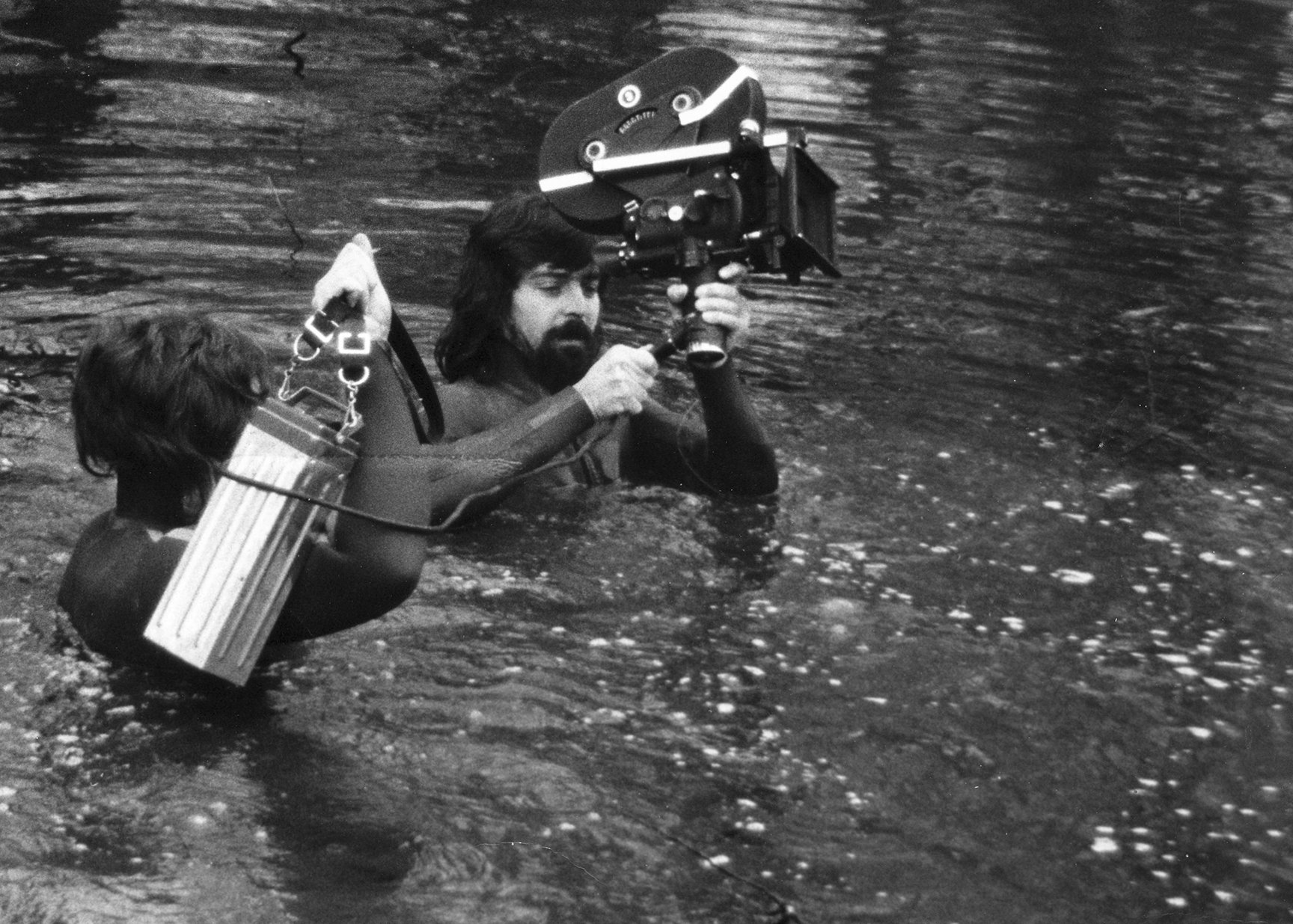

When Richmond got a call about another job a few months later, he had no idea he was about to work with the Stones again, this time under Jean-Luc Godard, one of his favorite directors. The film in question was Sympathy for the Devil, which juxtaposes 35mm documentary footage of the Stones with staged vignettes of acts of political rebellion. “Being chosen by Godard to shoot that was the highlight of my career,” Richmond says.

The film offers a behind-the-scenes look at the band developing the titular song, which was recorded at Olympic Studios in London. “Sympathy for the Devil was the first time anybody showed the process a major group goes through in making a song,” says Richmond. “[The track] started out as one thing, and it became something very different [over the course of filming]. The band was actually recording, so we had to stay out of their way as much as possible.”

Initially, the filmmakers intended to add very little lighting to the dim space. “I found the high-speed stock of the day — I think it was Ilford — to test. Then we tested a stock that was designed for recording optical sound because that was very fast.” But Godard decided he’d rather shoot in color, so Richmond used a 50 ASA Kodak stock and increased the light level accordingly.

“How we got away with that, I’ll never know! Godard was wonderfully crazy.”

The filmmakers had four days to be ‘flies on the wall’ at the studio. Each day, “we always knew where the boys were going to be because the engineer, Glyn Johns, and his assistant would set up the sound baffles and mics. And that was all we knew.” Quintessential rock stars, the Stones proved to be consistently unpredictable. “We’d get [to the studio] at about 6 in the evening. We never knew when the Stones were going to turn up. Sometimes it was midnight.”

Olympic Studios was a very difficult place to shoot, Richmond says. “The ceilings were very high, and we didn’t know how we were going to shoot as we couldn’t move lights for every shot like we normally would, because [the Stones] were recording. We laid 8'x4' sheets of plywood all over [the floor] so we could track [around the action] with an Elemack dolly.” Richmond had not operated previously, but “back when I was a focus puller, I’d get back from lunch very early and play with the gearheads, so I’d become pretty adept.” He worked with just a focus puller, Collin Corby, and a dolly grip, Teddy Tucker.

“Godard would tap the dolly grip to move the dolly and then tell him to stop; I’d pan around, find an image, get the shot, and then we’d go off again. It was really very exciting.” The camera was a rack-over Mitchell BNC, so Richmond had to line up a shot as best he could, rack over and then rely on the side viewfinder as a guide for what he was actually capturing.

The vignettes that did not involve the band members were all shot in London. “A car would pick me up in the morning, then we’d pick up Godard. As we were driving around, Godard would suddenly say ‘Stop!’ and get out, and I’d get ready to shoot — and then I’d run all over the place with a 35mm Arriflex and the focus puller. A few times, Anne [Wiazemsky], his wife, rushed across the road with spray paint and sprayed some cars. How we got away with that, I’ll never know! Godard was wonderfully crazy.”

The production’s distributors wanted to end the film with footage of the Stones performing “Sympathy” in its entirety, but Godard insisted such an ending would ruin the point. “The theme of the film is creation and destruction,” says Richmond, “and the idea was that creation is never finished, and destruction never ends.

David Bowie: Loving the Alien

“In my opinion, no one else could have played that character; Bowie was that character.”

By 1975, Richmond had mostly put the music world behind him. He was shooting for Roeg, and they had developed a shared sensibility. Roeg’s first choice to play humanoid alien Thomas Jerome Newton in The Man Who Fell to Earth was author/filmmaker Michael Crichton, who, at 6' 9", was ideal, but after Crichton dropped out, Roeg approached Bowie. “In my opinion, no one else could have played that character,” Richmond says. “Bowie was that character.”

Shot primarily in New Mexico with a British crew, the film relies more on visuals than dialogue to juxtapose the world of the brilliant alien with contemporary America. Our first glimpse of Newton shows him making his way down a steep slagheap after his spacecraft crash-lands in a lake. “I’ve always liked the opening sequence,” Richmond says. “We didn’t have Steadicam in those days, so we just followed him down with a handheld camera.” Soon we see Newton walking down a road where a large, inflatable clown-faced tent, seemingly left behind by a traveling circus, blows toward him. “That wasn’t planned,” Richmond notes. “The tent just happened to be at the location, and Roeg decided to work it into the sequence.”

Some aspects of the film’s look were unusual for their day — including the frequent zooms used as visual punctuation and the embrace of artifacts such as lens flares. “Till then, we almost always tried to get rid of lens flares,” says Richmond. “There’s a scene where Newton comes out of a pawn shop and sits by the river, amid quite a lot of lens flares. Normally, you’d have found a way to chop the light out of the lens, but it was summer, and the light was so low. We just decided to keep the flares, and I think it worked out very well. The Panavision C Series anamorphic lenses from that era are the best! They have a warm, soft quality that’s just wonderful for skin tones.”

The filmmakers were certainly cognizant of the fact that they were working with a rock star who was having ongoing issues with addiction. “You can see in the film that Bowie sometimes barely could hold it together,” says Richmond. Roeg managed to work around Bowie’s issues, which in the film seem to reflect the alien’s own failing health. “Despite his difficulties at the time, David was very professional — he always turned up on time, and he always knew his lines,” the cinematographer adds.

Looking back, he says, “There are problems on every production, but I like it when surprises are thrown my way. It’s why Nic and I got on so well — when something went wrong, he had a sense of humor about it. He wouldn’t start screaming and shouting and pointing fingers, but whoever made the mistake knew not to do it again. I hope that kind of approach has rubbed off on me.”

Don’t Look Now

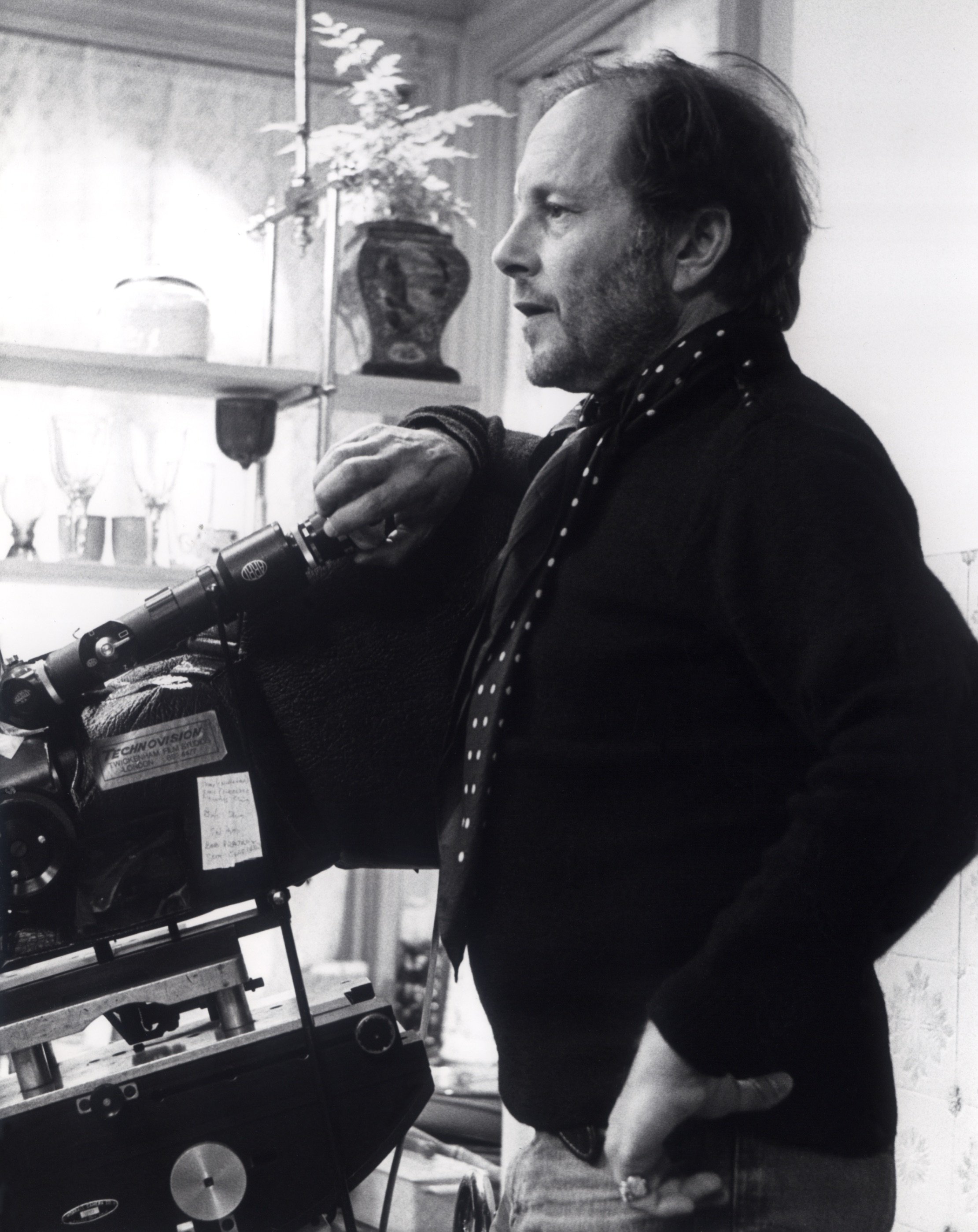

Nicolas Roeg’s 1973 feature, about a bereaved couple touring Venice, is famous for its nonlinear style and stark, haunting imagery. Richmond recalls that the assignment was initially “a bit daunting — I was shooting for a director who had been a cinematographer.”

He soon realized, however, that Roeg wouldn’t second-guess his work. “The only advice he gave me was, ‘Don’t be frightened of the dark.’ I didn’t know what that meant until we started shooting in Venice. He meant, ‘Don’t worry about lighting everything as long as you can keep the blacks black.’”

Like many cinematographers, Richmond would hit the filmstock with some extra exposure so he could subsequently print down for richer blacks. He realized how valuable Roeg’s advice was when he started lighting along Venice’s canals.

“It was a low-budget movie with a very tight schedule,” Richmond continues. “In February in Venice, it’s cold, miserable and dark. There were no Condors. Guys would climb up to balconies and hang 5Ks. We worked with carbon arcs in those days, massive Super Brutes. We didn’t have HMIs or anything like that.”

He used Panavision Super PSR cameras. “What I liked about the [Super PSR] is that at a 200-degree shutter, you could squeeze an eighth of a stop more out of it.” There also wasn’t a road for trucks carrying camera and lighting equipment, so they were limited to using canal barges. “We had one barge with the camera equipment and another with a generator and the lighting equipment. Sometimes the guys would be running around trying to get the barges out of the canals [and back to the open water] because the tide was coming in! If you didn’t move fast, you wouldn’t be able to get them out until the next day.”

Given the schedule, the filmmakers had to hope for “happy accidents.” One involved the weather in England during the short period the company had to shoot the opening sequence. “We shot four days before Christmas and got one of those extraordinary clear skies with that low wintry sun,” Richmond recalls. “The sequence works as well as it does because we struck it very lucky.”

Ravenous

Richmond is particularly proud of his work on this 1999 film, which blends cannibalism, humor and supernatural elements. He notes that upon its release, the feature was criticized for some of the very attributes that made the project attractive to him: It defies classification and audience expectations. “At the time, I was surprised that a studio was still interested in making that type of unconventional movie,” he says.

Richmond received the script from a studio executive at Fox 2000 Pictures who had recently decided, after about 10 days of shooting, to replace the original director and cinematographer. The cast and the remaining crew were on location, waiting to find out whether production would resume or be shut down. The executive told Richmond he had the night to read the script and needed to have an answer by the morning. “I thought the script was fantastic,” the cinematographer says. “He said, ‘I’ll book your tickets.’ It all took place in the [Sierra Nevada mountains], so I said, ‘Don’t bother. I’ll drive up [from Los Angeles].’ He said, ‘What are you talking about? We’re shooting interiors in the Czech Republic and the exteriors in the High Tatras mountains in Slovakia!’”

Richmond then flew to Prague with the new director, Antonia Bird. But when they arrived on location, Richmond says, “I didn’t like the way the set we were about to shoot was rigged. We had riggers work all night to rewire everything so that we could start shooting the next morning.”

Due to logistics on the remote location, he shot with the Panavision cameras and Cooke lenses that the production had already rented. “We couldn’t get many lights so high up in the High Tatras. The equipment we did have had to be dropped in by helicopter in cargo nets the night before.”

The cinematographer also recalls the strength of the production design, which was supervised by Bryce Perrin. “His sets were amazing,” Richmond says. “Behind every well-photographed picture is a very good production designer!”

For a cinematographer who had cut his teeth in the unpredictable world of rock ’n’ roll, the experience was inspiring. “Shooting Ravenous was wonderfully liberating because I had no prep at all.”

Richmond started his career in the film industry when he was just 19 years old, and he climbed to the rank of cinematographer within five years. From that moment onward, he has loved shooting movies. Richmond was invited into ASC membership on Feb. 4, 2000, after being sponsored by Haskell Wexler, Roy H. Wagner, and Stephen Goldblatt. He even shepherded both of his sons into the business: cinematographer George Richmond (Tomb Raider, Rocketman) and camera/Steadicam operator Jonathan “Chunky” Richmond (Black Widow, F9: The Fast Saga).