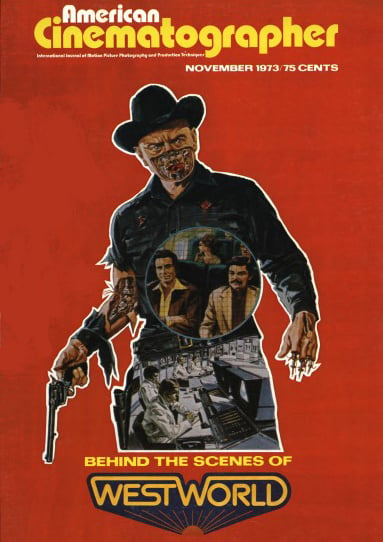

Behind the Scenes on Westworld: AC Talks to Writer-Director Michael Crichton

A strange trip through a fantasyland of the future, where, for a price, each person’s secret dream can come true — unless it turns into an eerie nightmare.

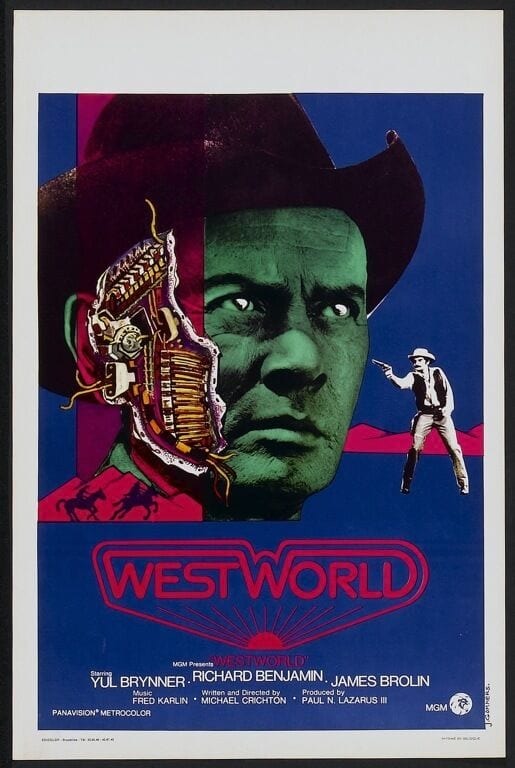

In these latter days, when the name of the game in feature film production is to create an entertainment that is unique and exciting enough to drag the viewers away from the "freebies" of television and into the theatres, a film like MGM's Westworld could serve as an example of what it takes. Completely "different" in its premise, and wildly imaginative in its execution, the film combines the highest degree of technical artistry with the salient dramatic elements that add up to sheer entertainment.

The very name Westworld conjures up images of action sequences from movies of the American frontier. But writer Michael Crichton has not simply told a western tale for his feature directorial debut, but provided Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer with one of the most novel action-adventure movies ever filmed.

Crichton has set his intriguing story in the world's greatest adult playland, Delos, a sophisticated amusement park that is a fantasy world utilizing space-age technology to recreate periods of the past in lifelike detail. Those who go there may actually immerse themselves in the life of a prior period in time. At Delos the periods include Medieval Europe, Imperial Rome and the American West as it was in frontier times—the latter is Westworld.

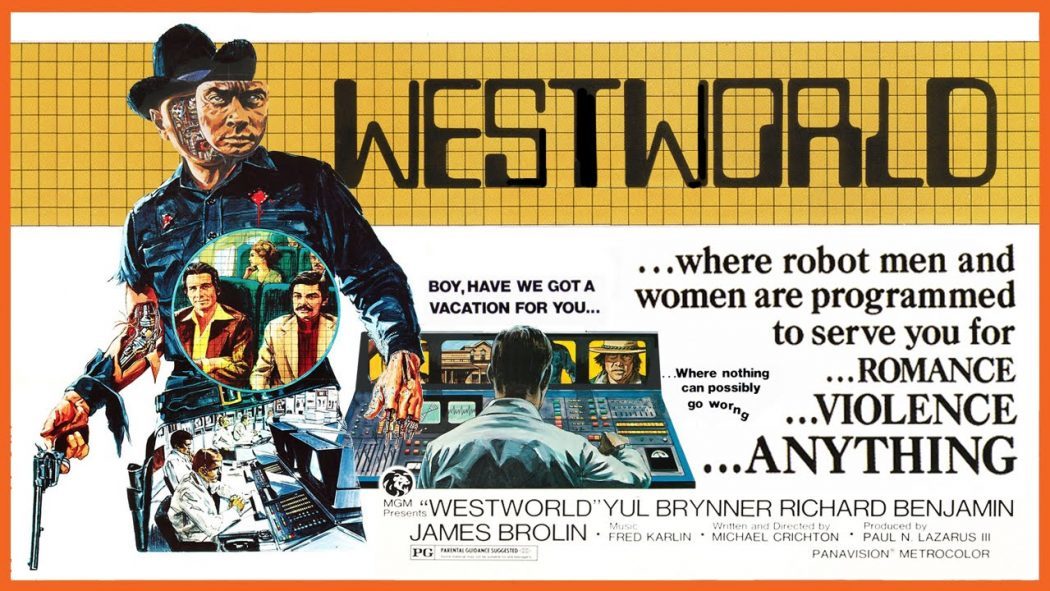

Paul N. Lazarus III produced this highly visual adventure which stars Yul Brynner, Richard Benjamin and James Brolin.

Westworld is a story of people in jeopardy. Two young Chicago businessmen, Peter Martin (Richard Benjamin) and John Blane (James Brolin) choose to vacation in Westworld, whose inhabitants are human-looking robots of the period. Malfunctions in the robots cause them to deviate from their programmed roles. The robot Gunslinger (Yul Brynner) in Westworld becomes the deadliest menace. He kills Blane in a gunfight and stalks Martin through the other worlds of Delos.

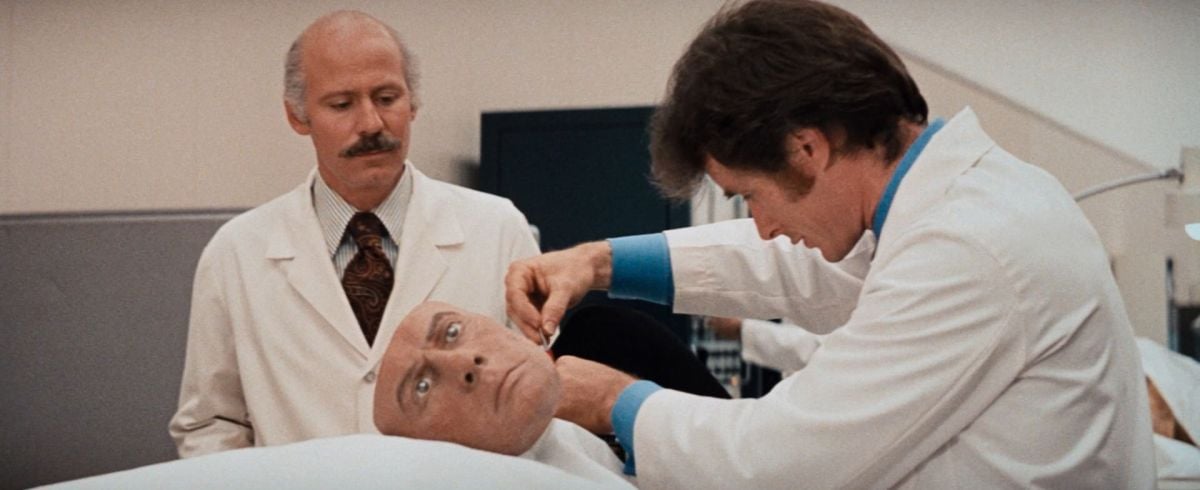

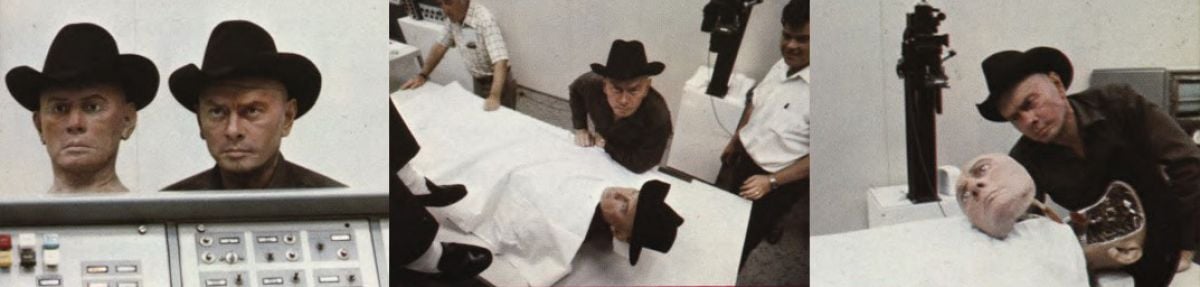

Guests pay $1,000 a day to relive the excitement of the Old West, including the opportunity to engage the Gunslinger in a showdown gunfight in which they are guaranteed to outdraw it and "kill" it. Each night technicians repair the Gunslinger and other damaged or malfunctioning robots, returning them to Westworld the following morning to repeat their roles as residents of a frontier town.

The electronic impulses which control the Gunslinger are so sophisticated, however, that it begins to react to the pleasure which the guests experience through the simulated killings. It gradually emerges from its programmed pattern, stimulated by an electronic urge to shoot back at the guests.

It no longer is willing to be a target, shot at over and over. It wants to do what its enemy does — a super-human reaction to a human act. And the closer it comes to killing, the more the robot experiences a satisfying warmth and becomes more of a human being.

After the Gunslinger undergoes its electronic metamorphosis, Westworld speeds to a gun duel between Brynner and Brolin, and Brynner's horseback pursuit of Benjamin through Westworld and the two other areas which comprise this vacationland of the future — Medieval World and Roman World. The climax comes in the computer control center where Benjamin tries to match his knowledge of electronic machinery against the programmed "brain" of the robot.

The various backgrounds needed were provided by desert landscapes in the Mojave Desert, the gardens of the Harold Lloyd Estate and the variety of recreations performed on several MGM sound stages. Special contact lenses were designed to distinguish the robots from the humans and computer filmmaking was utilized to give an accurate display of the robot's vision.

Writer-director Michael Crichton is one of the most successful young authors in the United States. Soon after entering Harvard Medical school in 1965, he completed his first novel, Easy Go, under the pseudonym John Lange.

Altogether, he has written 15 books under four different names. During his third year in medical school he completed a novel on abortion, A Case of Need which not only won the 'Mystery Writers of America Edgar Allan Poe Award' in 1968 and was recently made into the successful MGM thriller, The Carey Treatment.

Crichton has decided never to practice medicine but has written a non-fiction account of patient care, Five Patients, based on his experiences at Massachusetts General Hospital.

The Andromeda Strain was the first book to appear under Michael's own name. During his post-graduate year at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, the book became a best seller and stayed on the list for six months. Producer-director Robert Wise (who would later shoot Star Trek: The Motion Picture) bought the book and made the film into his greatest success since The Sound of Music. Soon afterward, Michael and his brother completed a novel about marijuana, Dealing, which was made into a film by Paul Williams.

Last fall, Michael got his first chance to direct for television. Robert Dozier scripted his book Binary, which Michael directed as Pursuit, an ABC Movie of the Week. Another book, The Terminal Man, was sold for a large advance and is presently being filmed.

Crichton's latest project, Westworld, is an original for the screen and represents his feature film directorial debut.

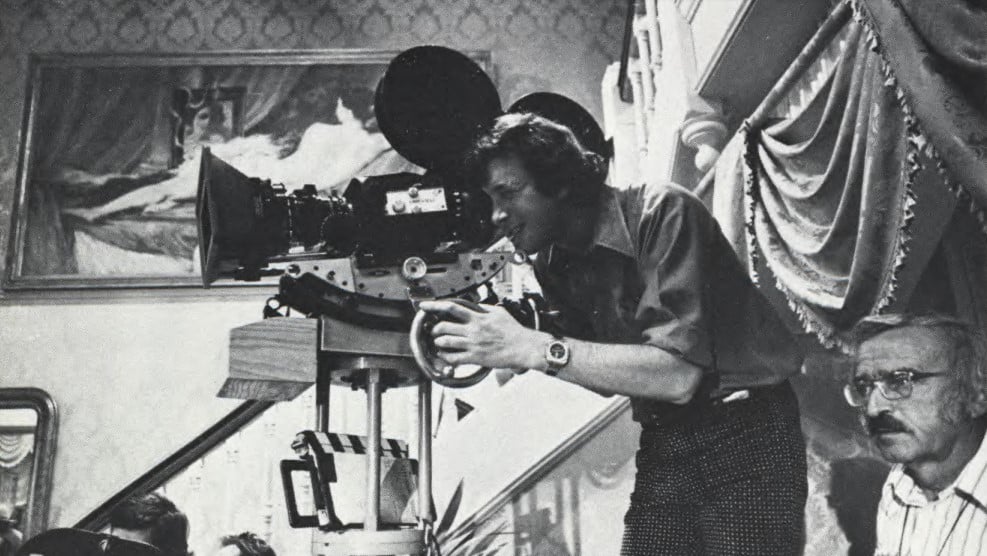

Crichton is fascinated by film and wanted a certain visual style for his picture. Cinematographer Gene Polito, ASC achieves the style perfectly. Best remembered for his camera work in Colossus: The Forbin Project and Prime Cut, Polito has been receiving well-deserved critical accolades for his bright, colorful style.

In the following interview for American Cinematographer, Crichton goes behind the scenes of Westworld to talk about his conception of the basic idea, his writing of the screenplay and his experiences in translating the script into his first theatrical feature, as director.

American Cinematographer: The basic premise of Westworld is extremely imaginative. Can you tell me what inspired you to approach such a subject and, subsequently, to make it into a film?

Michael Crichton: I'd visited Kennedy Space Center and seen how astronauts were being trained, and I realized that they were really being trained to be machines. Those guys were working very hard to make their responses, and even their heartbeats, as machine-like and predictable as possible. At the other extreme, one can go to Disneyland and see Abraham Lincoln standing up every 15 minutes to deliver the Gettysburg Address. That's the case of a machine that has been made to look, talk and act like a person. I think it was that sort of a notion that got the picture started. It was the idea of playing with a situation in which the usual distinctions between person and machine — between a car and the driver of the car — become blurred, and then trying to see if there was something in the situation that would lead to other ways of looking at what's human and what's mechanical.

I understand that you originally tried to write it as a novel and then abandoned that tack in favor of writing it directly as a screenplay. Why was that?

Well, it didn't work as a novel, and I think the reason for that is the rather special structure of this particular story. It's about an amusement park built to represent three different sorts of worlds: a Western world, a Medieval world and a Roman world. The actual detailing of these three worlds — and also the kinds of fantasies that people experienced in them — were movie fantasies, and because they were movie fantasies, they got to be very strange-looking on the written page. They weren't things that had literal antecedents, literary antecedents. They were things that had antecedents in John Ford and John Wayne and Errol Flynn — that sort of thing. In some ways, it's a lot cleaner as a movie, because it's a movie about people acting out movie fantasies. As a result, the film is intentionally structured around old movie cliché situations — the shoot-out in the saloon, the sword fight in the castle banquet hall — and we very much tried to plan on an audience's vague memory of having seen it before and, in a way, wondering what it would be like to be an actor in an old movie.

Is this the first time you've written a screenplay directly, instead of adapting it from one of your novels? If so, what differences do you find in the two methods?

No, it's not the first time. I've done some other original screenplays, most of which have never been made, but I've written them directly as screenplays. I've also adapted my own books, and I think that the two methods are really very different — more different than most people ever realize. The Hollywood tradition has been to purchase books and stage plays and short stories and then hire a group of screenwriters to adapt them. But the screenwriters, in most cases, were not people who wrote books and stage plays and short stories themselves — so there were very few people who found themselves in the position of writing a book and then adapting it into a screenplay. I think the differences in the two forms are incredibly great, and they go beyond those platitudes that everybody hears about — telling the story in visual terms, and so on. In fact, it often becomes a question of what kind of story you're telling. That's why I feel that, of the books that have been successfully adapted, there often isn't a great deal of the book that is retained in going to the screen. What is retained is a certain feeling, some essential quality that was in the book and that also appears in the film. That's also why I think that you can have a really slavish adaptation that follows the original scene-by-scene, with all of the characters remaining unchanged and everything exactly the same as it was in the book—but it's no good as a movie. Some kind of emotional quality has been lost. I don't think there's any way to get around the fact that to create that emotional quality on paper is very different from creating it in terms of images.

Obviously, in writing a novel, you can get inside the heads of the characters. You can tell what they're thinking. Have you found that a difficult thing to translate into visual terms, without falling back on long subjective speeches?

I just think of it as something that you can do well in one medium and not in another. All internal states of mind are very hard to film, because either you have the character say something — which is almost always phony — or you have the character do something to tie in with his emotional state. That's often rather clumsy and awkward and certainly time-consuming. It may take you quite a long time to convincingly show that the character is depressed, in terms of our almost cliché conventions with the audience. The audience will say to itself, "I know what that gesture is. I've seen it a thousand times. That means he's depressed." It's like the convention of having wavy lines on the screen to indicate the start of a dream sequence. There's nothing inherent in that sudden sort of water image that means "dream," except that the audience has been conditioned to interpret it that way. Internal states are awfully hard to portray visually, whereas, in books, they're very easy. All it takes is a line of dialogue: "I came home and I was very depressed." That's it. You've done it — and you don't have to justify it.

“One of the things we tried to do in Westworld was to let the audience find out about a character through what he does, instead of having him sit back and tell a little story about himself or his past.”

Do you think that there are some things that are easier to portray on the screen than in a book?

Yes. At the other extreme, any kind of description in writing is lengthy, whereas, on film, it's instantaneous. Exactly the reverse situation applies. You can spend a page describing how somebody looks, the way he acts, the way his surroundings are, what kind of house he lives in. In film, all of that is immediate. You show it — and that's it. Certain traditions have sprung up to try to get around limitations of the medium and one of them is what I call the "verbal flashback," in which a character who finds a moment of repose tells an anecdote or incident out of his life which reveals his character. It's the kind of thing that almost never happens in real life, but it's been a sort of movie trick to define character for a very long time. One of the things we tried to do in Westworld was to let the audience find out about a character through what he does, instead of having him sit back and tell a little story about himself or his past. I think of this as using the unique qualities of the medium.

In translating Westworld from the script onto the screen, you adopted a certain visual style, in terms of photography and action. Can you tell me something about that style and why you chose it?

The style, I think, is very straightforward — very conventional and very traditional. In many ways, it's the way the film would have been shot, sequence-by-sequence, had the sequences appeared in a 1940s Western or a ’40s version of Robin Hood. We had very little hand-held work — almost none. We had, to the extent that it was possible, unobtrusive camera moves. It was designed to be a picture that didn't shriek "Director of Photography" — but, rather, it kept those qualities in the background and tried to push the story up front. We had two specific reasons for doing the story in that way. One was that, because we were trying to suggest that the characters were trying to live out old movie fantasies, we attempted to shoot those fantasies as they used to be shot, at one time, even though those conventions are not used so often any more. For example, there was one instance in which we broke away from our desire for unobtrusive camerawork, just for this reason. That was in our exterior Western street sequences. Everything was a crane shot because, as far as I can tell, all the old Western movies had crane shots. The camera went up or down every time the good guys rode into town or the bad guys rode out of town. There was always a vertical camera move, for reasons which I never really understood — but we did it, too. The other reason for shooting in that sort of conservative way is that the story itself is very strange and, in such a case, I think that there is always an enormous temptation to shoot it strangely, to have bizarre combinations in very odd framings and to cut people's faces in half in order to use extreme closeups. My feeling was that the strangeness of the story would, in fact, be emphasized by conventional shooting, rather than by a photographic style which kept saying to the viewer: "Isn't this odd? Isn't this odd? Look how odd it is. We're even going to shoot it odd."

“The picture would have been miserably difficult to do even with a long schedule, but we had a 30-day schedule and getting it all on film the right way seemed close to impossible.”

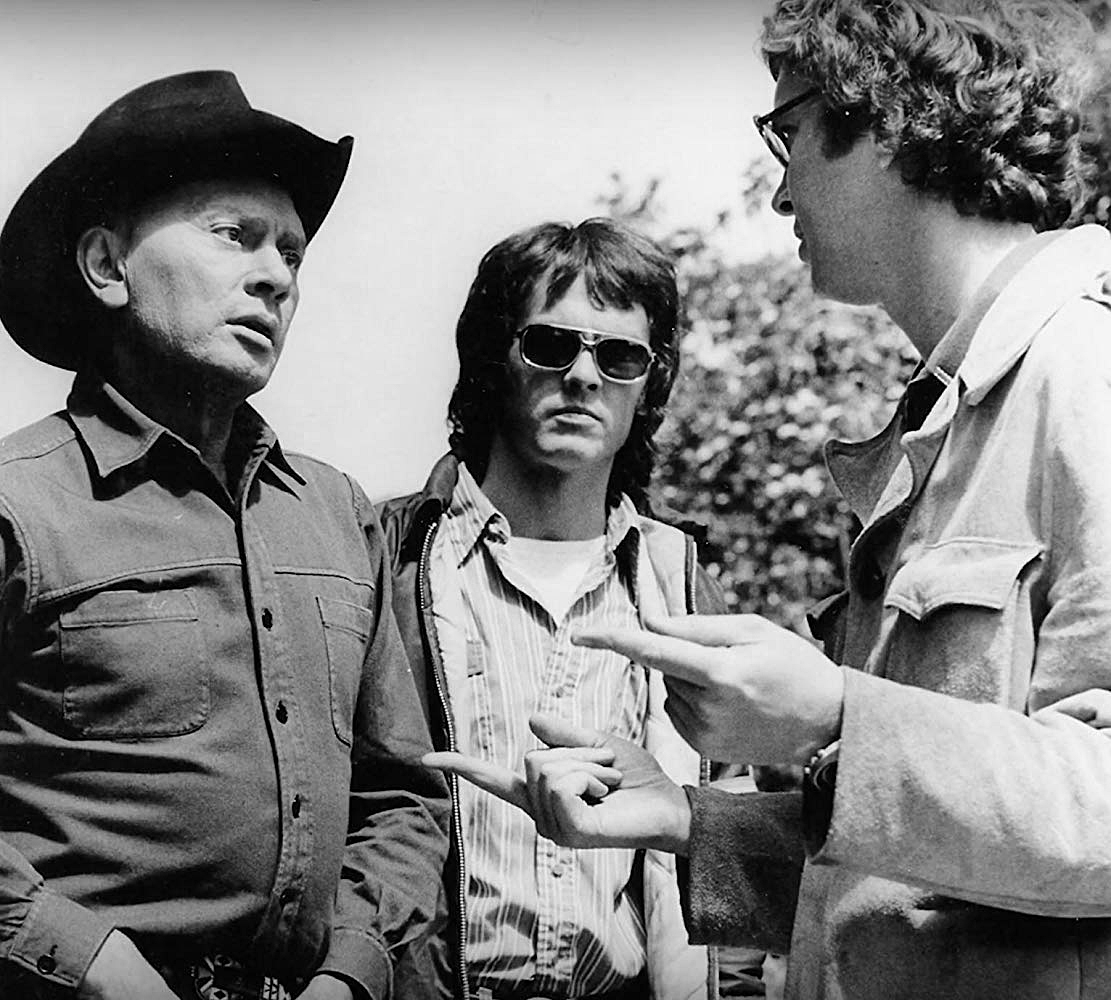

In regard to Gene Polito, your director of photography on Westworld, can you tell me something about your method of working together, the rapport established between you, and his ability to translate into visual terms what you had in mind?

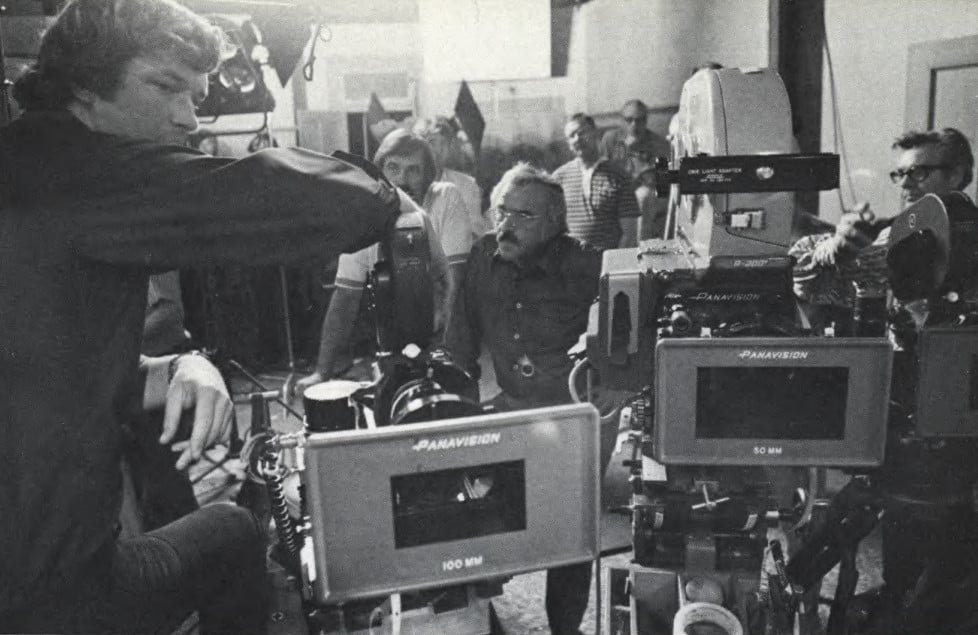

I'd known about Gene's abilities because of the work he'd done with Michael Ritchie, whom I admire, and I felt that he would be able to handle the very special problems we would encounter on this film. We wanted the picture to have a kind of "classic" look to it — but we were given a very, very short shooting schedule and we had an enormous range of technical problems. The picture would have been miserably difficult to do even with a long schedule, but we had a 30-day schedule and getting it all on film the right way seemed close to impossible. Gene is terrifically well-organized and tremendously competent in technical areas, which, for this picture, was enormously important. We had a wide range of special effect situations and technically challenging problems — which certainly frightened me because of what I didn't know about such things. We were shooting rear-screen and front-projection and bluescreen and color video re-photography, and we were shooting certain of the actors wearing mirrored contact lenses. We filmed a lot of the picture at very low light levels and we were moving incredibly fast, so that we were forced into multiple-camera situations more than any of us would have liked — especially with Panavision, because it gets hard to squeeze those cameras around when the picture is so wide. Gene is just terrific for all of that. We moved so fast that nobody could believe it, and we couldn't believe it ourselves while we were doing it. We made 52 set-ups one day and 47 the next day, while we were at Warner Bros, shooting exteriors on the Western street — and we'd sit around at the end of the day and marvel at how we'd gotten through it.

“We were doing a lot of sort of smart-guy, first-time-director stuff.”

You mentioned the use of multiple cameras. Would you like to elaborate a bit more on how and why you used them?

It was strictly in the interest of efficiency and being able to save a lot of time, with no sacrifice to the kind of picture I was after. I’ve had a lot of complicated action and there were a lot of things we couldn't afford to do twice. If there was a large piece of breakaway glass or a specially equipped suit that was destroyed, we used multiple cameras because we couldn't repeat it. We didn't have the budget for another piece of glass or whatever. The production people were very much opposed to our use of multiple cameras, arguing that it would be cheaper to stage the stunt again, but I think we demonstrated convincingly that this was not true. There were several situations where we were using normal speed and high speed in the same set, and Gene suggested that if he put the ultra-high-speed Panavision lens on the Mark II camera, he would not have to relight. The only question was whether I could live with the 55mm lens — which I was very happy to do. It kept the actors a bit cooler, also. A lot of the time we were shooting at 5 foot-candles. By the time we hit 12 or 15, everybody began to relax and say: "This is no big problem." When it got up to 30, nobody had any sympathy for Gene at all. After all, it was 30 foot-candles. Anybody could shoot with that. He demonstrated early on that he was fine working at those levels, so that's what he did.

Even though you've spoken of a "straightforward" photographic style, it would seem to me that the very nature of the story would demand techniques that were somewhat less than conventional; isn't that so?

Actually, yes. For example, Gene shot many of the exteriors without the 85 filter, and we tried a lot of other things, little tricks and innovations that came to mind, but we ultimately abandoned most of them. Some of our sets were entirely white and Gene tried various combinations of underexposing and forcing development to see what would happen to the contrast. The MGM lab had been alerted to this, but the guys down there were terrified all the time. Also, we were doing a lot of sort of smart-guy, first-time-director stuff. For example, we had a couple of 360-degree and 720-degree shots and Gene, to my astonishment, never batted an eye. I really expected to hear him say something like, "You can't do that" or "It will take a day to light it " — but that never happened. I'd say, "Now, we're going to do a 360 here" and he'd say, "Yep, all right." There was no sort of reaction at all. It was a very strange experience.

“[American Cinematographer] was a kind of gold mine for me because it’s full of articles telling in precise detail how, on specific projects, certain techniques were used and problems solved. It was difficult for me at first, because I didn’t have the background to understand it, but then, after I’d become more comfortable with the medium, it was really terrifically valuable.”

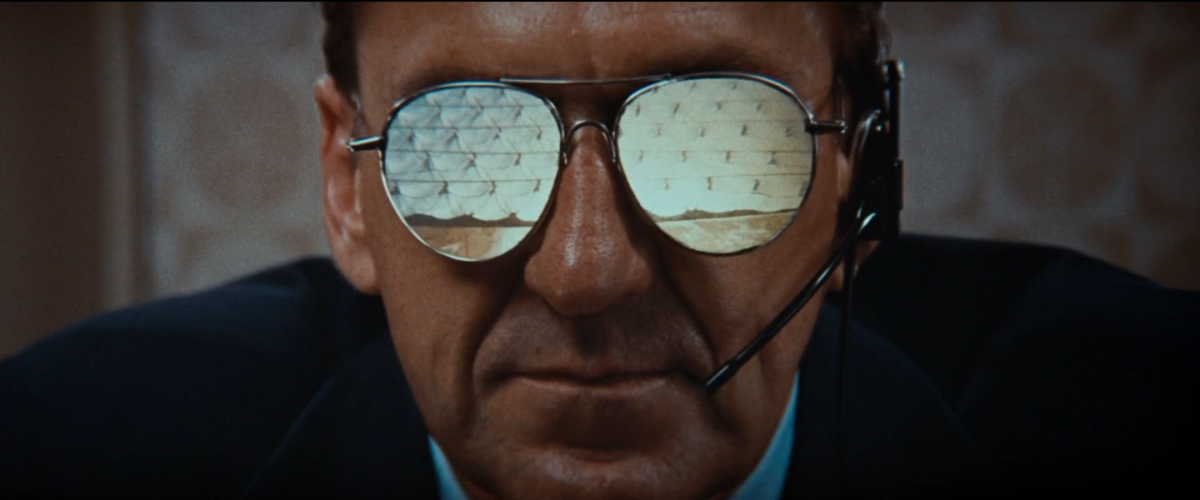

What about the special footage that had to be shot for the video monitors and also to provide John Whitney, Jr. with what he would need to make the computerized robot point-of-view shots?

Along with our regular production footage, we were shooting two other kinds of special footage. We were shooting flat film for transfer to video tape, so that we could later re-photograph it off of video monitors. We were also shooting footage that was going to be processed by computer to represent the robot point-of-view. This was a kind of hazardous situation and we were a little bit concerned about it. The computer program that was going to generate the final footage had been worked out by the time we started shooting, but the tests were disturbing because of the variety of options they offered us. It wasn't clear exactly what the computer required, except that it wanted a lot of contrast. We shot it that way and later discovered that it was easy to increase contrast within the computer itself. We finally began to pull other footage that we hadn't expected to give the computer and fed it less contrasty stuff. Color contrasts were important. As a result, for our exterior sequences, a poor fellow who was to double for Dick Benjamin was done up entirely in red. His hands and his face and his clothing were all bright red, because, when he was standing against a blue sky, we didn't want to lose him. Then we had another sequence where Benjamin was in totally white makeup.

I'm sure you've been asked this question a million times, but I know that our readers will be interested to learn how and why, having gotten your degree as a medical doctor, you ended up writing and directing films. It seems like quite a switch.

Well, it does seem strange, but I think it's what I always wanted to do. The only other doctor I know of who's done the same thing, Jonathan Miller, has said something which I think is true — namely, that being a doctor is good preparation for this, because it teaches you to deal with the kind of life that you will inevitably have. It teaches you to work well when you haven't had enough sleep. It teaches you to work well when you're on your feet a lot. It teaches you to work well with technical problems and it teaches you to make decisions and then live by them. I think it also has advantages in working with actors, because one of the things a doctor has to learn is to be able to meet a patient whom he has never seen before and rapidly assess him in terms of what kind of person he is, and not merely whether he's perforated his ulcer. You've got to be able to analyze just what kind of person you're dealing with. Are you dealing with someone who will take medicines if you prescribe them — or is he the kind of person who says he will, but won't? Those decisions get to be very important and training to be a doctor builds up that capability for assessing people rapidly which is necessary when it comes to working with actors. I'm not quite sure just how the transition from medicine to movies came about, except, as I've said, that I think I've always wanted to make movies. When I got into medicine, I was disappointed in a lot of ways, so it was a pull from one direction and a push from the other.

As we all know, you went through an intermediate stage of being a novelist, but making a film is quite different from writing a novel. How were you able, in such a relatively short time, to learn the methods and mechanics of something as enormously technical as film production?

I'd had one previous experience in film directing before Westworld and that was the television movie Pursuit, which I did for ABC. That was also a very difficult production situation — one of those situations where you were glad to have gotten it finished at all. The cameraman on the project was Bob Morrison, who really just took care of me. In fact, a lot of people took care of me, including the actors. I learned very fast because I had to learn fast. There were thousands of things to learn, all kinds of details which I'd had no idea about. But I just did it because I had to. It was a very fast course.

Were you able to augment your technical knowledge by means of any extracurricular study — books on the subject, and so forth?

For someone who was not brought up in film, it's very hard to get any kind of specific technical information about filmmaking — l mean, the sort of "case history" information that tells precisely how certain things were done. The two ways that I know of to learn such things are: (1) a sort of general explanation from someone who sits you down and says: "If you want to diffuse a lens, you can do this or that..." and (2) what I call the "case history," which is someone telling about what happened on a certain project — what problems there were and how they were dealt with in a specific way. The stuff that's in print in books is pretty awful. At least, that's been my experience, and I gather it was Mike Nichols' as well, when he did Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf as his first picture. The books just don't tell you very much, except for things like, “If you choose a low angle, it's more dramatic.” That's not terribly valuable. But for the "case history" sort of thing, I found that the American Cinematographer is terrific. It was a kind of gold mine for me because it's full of articles telling in precise detail how, on specific projects, certain techniques were used and problems solved. It was difficult for me at first, because I didn't have the background to understand it, but then, after I'd become more comfortable with the medium, it was really terrifically valuable.

“[Director] Bob Wise was really very nice about letting people watch and learn from what he was doing. I was just the writer of the book hanging around the set [of The Andromeda Strain] — which was a totally non-existent function.”

I understand that you spent quite a bit of time on the set of The Andromeda Strain when it was being filmed. Did you find that experience helpful to you later when you started directing?

Bob Wise was really very nice about letting people watch and learn from what he was doing. I was just the writer of the book hanging around the set — which was a totally non-existent function. But he had, as I recall, an AFI intern and a Director's Guild trainee on the project, mostly just watching. I had never seen any kind of a film made before, except during brief visits to stages for a few minutes. Bob was the first director I'd ever had a chance to observe at work and, in an awful lot of ways, he's the model I've retained. Bob dealt with all of the problems very smoothly. His particular style of directing is very relaxed, very easygoing, very personal and very well-organized, but without a lot of histrionics and temper flares. That impressed me a lot and I've tried very hard to be that way, too.

Without getting into one of those ivory-tower, esoteric discussions, may I ask what you would like to accomplish with film. In other words, what is your objective in making pictures?

The first thing I'd like to say about film is that, because it's so expensive, it has to be supported by a very large audience. That's a really significant difference between a film and, let's say, a book. A publisher can sell 4,000 copies of a book and still come out all right financially, but a film that is seen by only 4,000 people is a disaster of almost unheard-of proportions. A much larger audience is necessary to make filmmaking commercially viable. I'm not talking about an enormous commercial success, but rather a sort of break-even situation that will allow you to continue to engage in the activity. Therefore, the potential audience exerts an unmistakable pressure on what you do and how you do it. With Westworld, I chose to do what I regarded as a blatantly commercial film, and I don't think there's any harm in that. I believe it's possible to make less-commercial films — films that are more idiosyncratic in terms of what the filmmaker wants to say — without nullifying the possibility of the film breaking even or becoming moderately successful. Television is really the mass audience medium, whereas, feature films are inching more toward specialized audiences. My approach to licking the problem is that I try to do things that can be taken in different ways. If you want to look at Westworld as a kind of science-fiction shoot-'em-up, that's fine. If you want to look at it as a sort of bemused allegory, you can do that, too. One interpretation does not make the other impossible. In that sense, my model is something like Lord of the Flies, which is a very good story on one level and a very profound story on the other. But it doesn't insist that you recognize it as profound. That's the sort of thing I want to do.

Do you have any film plans for the future that you'd care to talk about?

Well, I'm having trouble going back to writing now. It's hard to sit there alone. I've been trying for about a month now and I'm only just beginning to enjoy the fact that people aren't walking into my office and saying: "Would you please make a decision about the color of the floors?" There's a lot of excitement in making movies. I think I've learned two things from the experience. One thing is that the people who gripe about the whole movie-making situation and claim that there isn't enough money, and so on, are the people who sabotage projects. It's really a phony thing, and they ought not to be allowed to get away with it. I think it's necessary to be able to work within your strictures, even when those strictures are so impossible that you're ranting and raving and screaming about the studio executives, like everybody else. Once you settle down, those strictures provide a certain sort of creative impetus and the result is something better than if you'd been given all the money and all the time you wanted and that guy in the front office had said "yes" every time. That kind of discipline produces a tighter, more inventive kind of film. The other thing I've found is that it's really fun to make movies. It's so much fun! It's really awful to be paid for doing it. I really miss that excitement now that I'm writing again. I don't find the writing so much fun anymore.

If you had Westworld to do over again, is there anything you would do differently?

I really feel that this experience has convinced me more than ever that pre-production is the key to it all — especially with a tight shooting schedule. We had no rehearsal time — which is bad — and we could have used more test time. All of that I log under pre-production, and I will never do another picture without adequate preparation in that area. To the extent that studio executives do not understand this fact, they're just fools. Pre-production saves them money. It may cost them $2,000 a day, but it will save time on the set that often runs to more than $2,000 an hour.

You'll find our feature story on the film’s cinematography written by Gene Polito, ASC here.