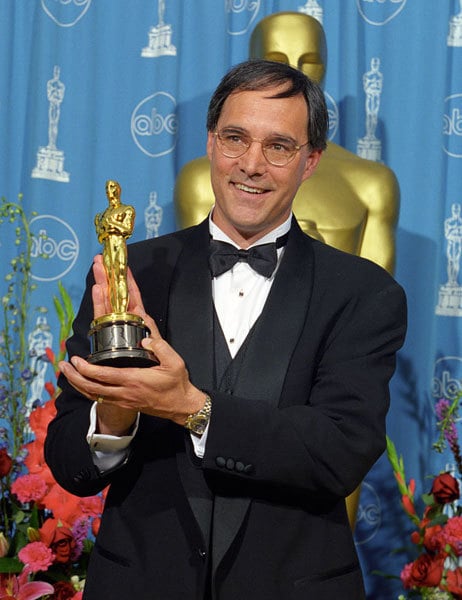

Russell Carpenter, ASC: Passion for the Craft

The 2018 ASC Lifetime Achievement Award honoree recounts the rollercoaster ride that led him to Titanic and beyond.

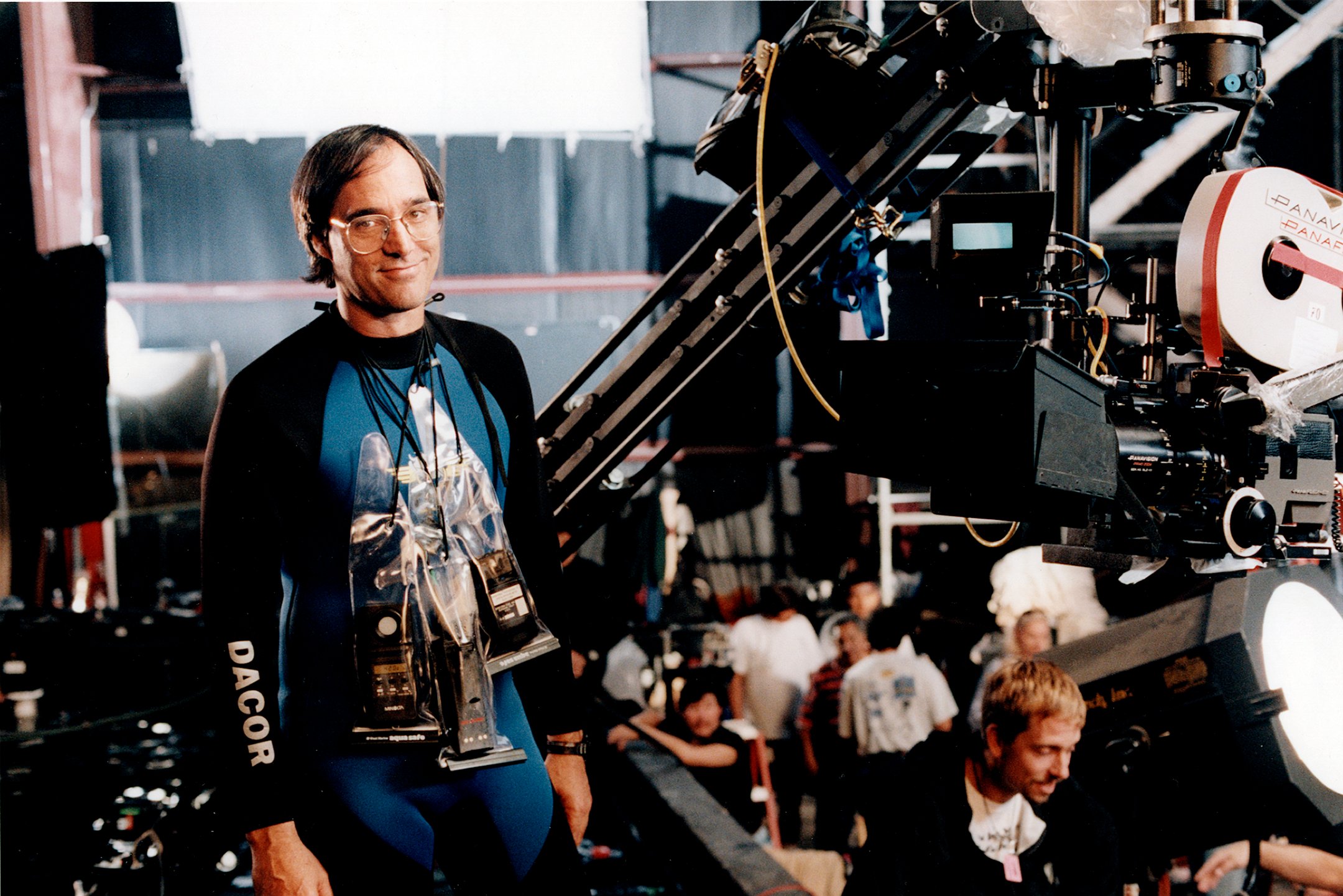

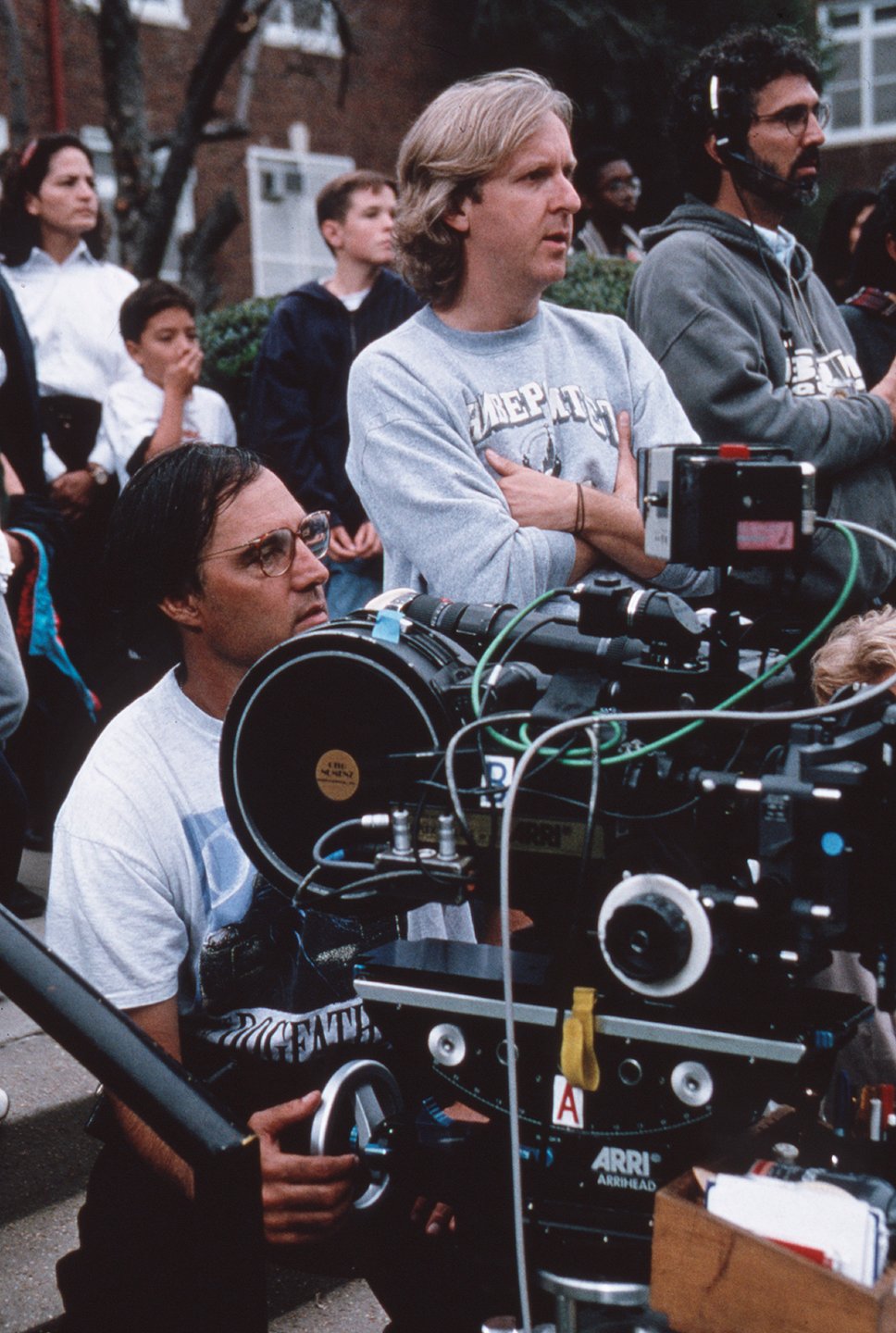

When James Cameron hired Russell Carpenter, ASC — this year’s recipient of the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award — to shoot the feature True Lies, it was the cinematographer’s first shot at a massive-budget, tech-heavy science-fiction project, though nobody could say Carpenter hadn’t paid his dues. Having worked his way up from low- to modestly budgeted horror films like Pet Sematary II, Critters 2, The Lawnmower Man and others, the spy thriller starring a peak-of-his-popularity Arnold Schwarzenegger was a great leap in Carpenter’s evolution. The enormous success of True Lies paved the way to Cameron and Carpenter’s feature reteaming for Titanic — which earned Carpenter the Best Cinematography Oscar — and to more than 20 features that followed, including The Negotiator; Shallow Hal; and a small Indian film called Parched, which the cinematographer is quite proud of. It’s been a long road, filled with surprising ups and downs, but to hear Carpenter and his colleagues tell it, he’s always loved the work.

Growing up in “deepest, darkest Orange County” in the 1960s, Carpenter might as well have been a thousand miles from Hollywood. His mother worked at Ford Aeronautics. “The gift of having a working mother with four children is that we all became tremendously independent,” he says. “It’s not like nobody was taking care of us, but after school, we were left to our own devices, had our own friends and interests, and were able to develop that way.”

Long before the idea of becoming a professional cinematographer had even occurred to Carpenter, his interest in making Super 8 monster movies with friend Chuck Woller hinted at where his interests lay. In the summer of 1967, he attended a class in media. “Two teachers ran it and we talked about music and they showed us films,” he recalls. “At that time, I was interested in things like King Kong and the Japanese film Godzilla, but they showed us two films by Ingmar Bergman: Wild Strawberries and Persona. I hardly understood anything about Persona, but the imagery, especially the opening, just grabbed me by my teenage t-shirt and yanked me out of my chair. I just felt it was so powerful. That was the first flicker of, ‘My god! This medium has the power to move me like no other.’”

At the suggestion of older sister Maureen, Carpenter transferred to a high school with an audiovisual program, where he learned to shoot pedestal-style TV work, which he enjoyed and had a flair for. He then sought out ways to feed his interest at San Diego State College (now State University). “I didn’t have the money to get anywhere near USC or UCLA,” he recalls, “and those places were ferociously intimidating to me at the time.”

It was in college where he met “a really generous man named Paul Marshall, a producer and manager at KPBS-TV, a PBS affiliate. He kept encouraging me. I think he was the first person who said, ‘It looks like Russell has a gift for working with images.’” When an opportunity arose to work in the station’s film department, Marshall offered each of five applicants a 100' spool of black-and-white reversal film and access to a camera, and told them to come back with a visual story edited entirely in camera. Never shy of a challenge, Carpenter, Woller and another close friend — now college classmates — went to nearby Belmont Park to shoot 68 several-second shots, in sequence, of Woller’s regret-filled rollercoaster ride. Carpenter carefully shot-listed what he’d need, which involved his subject taking a full 68 trips, and Carpenter covering the action from multiple vantage points, which included joining Woller a good 40 times around. The park was surprisingly willing to let the two students monopolize the particularly rickety coaster all day. “I could barely speak at the end of that day, but it got me the job,” Carpenter recalls. “I was working for the station and learning a lot more than I was in my classes.”

Carpenter majored in English, a degree that “had nothing and everything to do with filmmaking,” he says. “I read a lot and it gave me a knowledge of structure and story.” After graduation, the station offered him a full-time job shooting film documentaries as a cinematographer in residence. But the job offered too little cinematography and too much “in residence” — i.e., sitting behind a desk — and he quit without a clear direction forward.

After spending some time hiking around Hawaii, eating peanut butter, and sleeping on beaches, he returned to Southern California and found work shooting at another Orange County public TV station. A director there, Thom Eberhardt — who later went on to direct such films as Night of the Comet — presented Carpenter with an opportunity to shoot a feature. Eberhardt had convinced a local “furniture czar” in Orange County to finance a zombie movie to the tune of about $250,000, under the stipulation that the financier’s wife would portray the most prominent zombie. “It was the first time I ever got to shoot 35mm film, and it was the first time I shot anything over 20 minutes or anything that was truly narrative,” the cinematographer recalls of this unexpected opportunity.

The zombie movie saw short runs in a number of theaters. This early success gave Carpenter the encouragement he needed to pursue a career shooting feature films, but not before he faced the inevitable artistic right of passage: criticism. “It was a tiny [piece in the Los Angeles Times], and it was not a glowing review of the cinematography by any means,” Carpenter says. “I remember words like ‘murky’ and ‘dismal.’ I’d seen it as moody! It was like someone had thrown a javelin through my jugular. I was stunned to see something so negative about what I was doing. There are all kinds of lessons you have to learn in this business, and a big one is to develop a thick-enough skin. There is always the next thing. You have to take reviews with a grain of salt and move along.”

He thus resolved to make the 40-mile voyage and move to Hollywood, though it seemed all his competitors had better reels. Carpenter notes, “It was a time when shooting features, documentaries, corporate work — anything!” seemed out of his grasp. Yet, “as formidable as Hollywood was, even if people couldn’t offer me anything, a lot of them were pretty nice about it. Some people were really gracious and encouraging.”

While he searched for work, he used available resources as his own version of film school. “I was watching a lot of movies and starting to read American Cinematographer to find out what was happening behind the scenes of films that I really enjoyed,” Carpenter says. “I was starting to devour the magazine, which, at that time, was just about the only thing you could turn to that had anything to do with the filmmaking process, especially in terms of cinematography.” He complemented his studies with weekend screenings and filmmaker presentations at the AFI. “Caleb Deschanel [ASC] showed The Black Stallion, and later The Right Stuff,” Carpenter recalls. “And I was just going, ‘Oh my god, he’s so young and look at the magnificence of his work, and I’m still skiing on the bunny slopes of cinematography.’ That wasn’t exactly encouraging, but at least I knew I could learn something from the incredible people who came and spoke.” (Deschanel and Carpenter would later both work on Titanic, with the former shooting the modern-day sequences.)

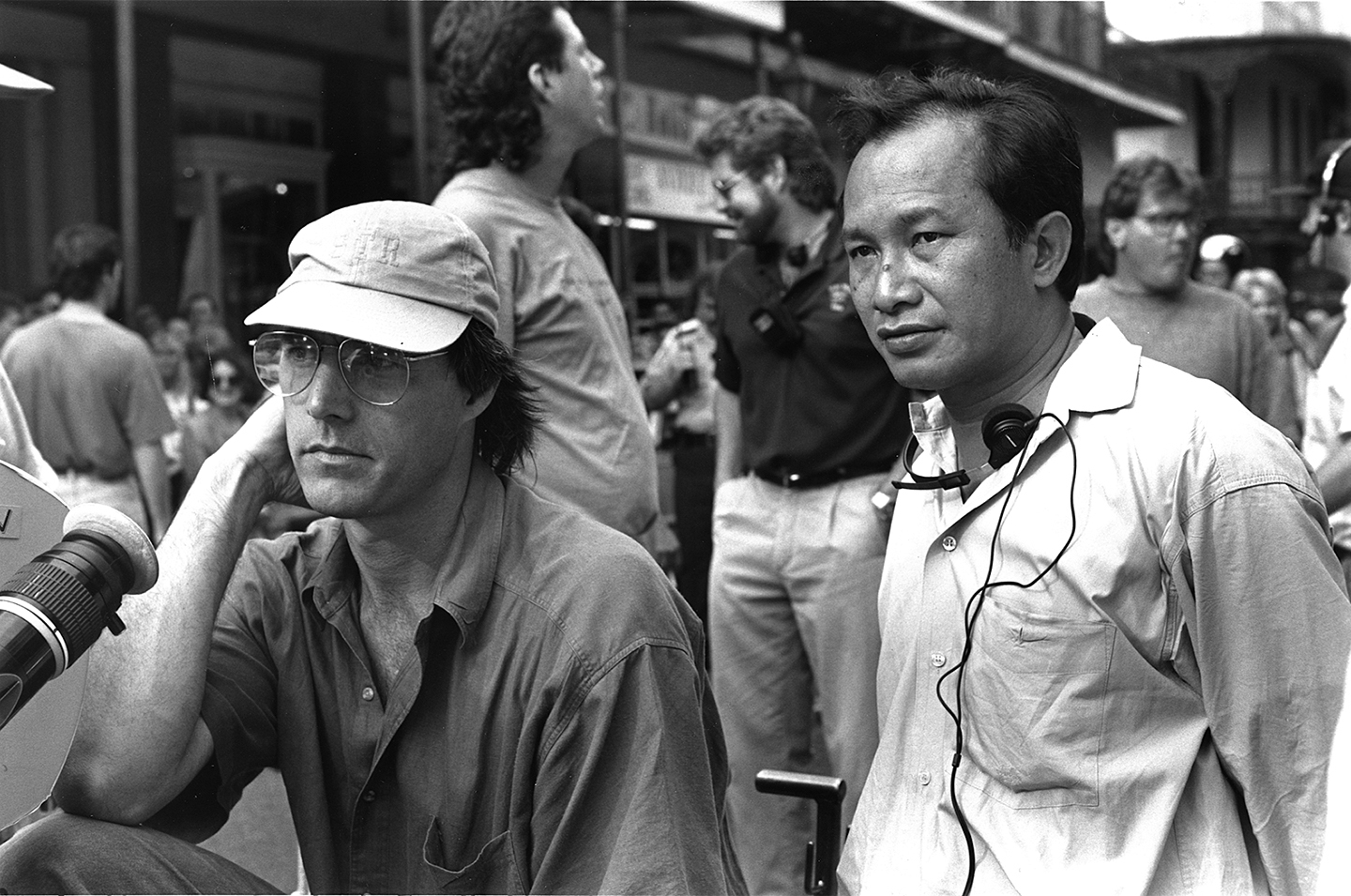

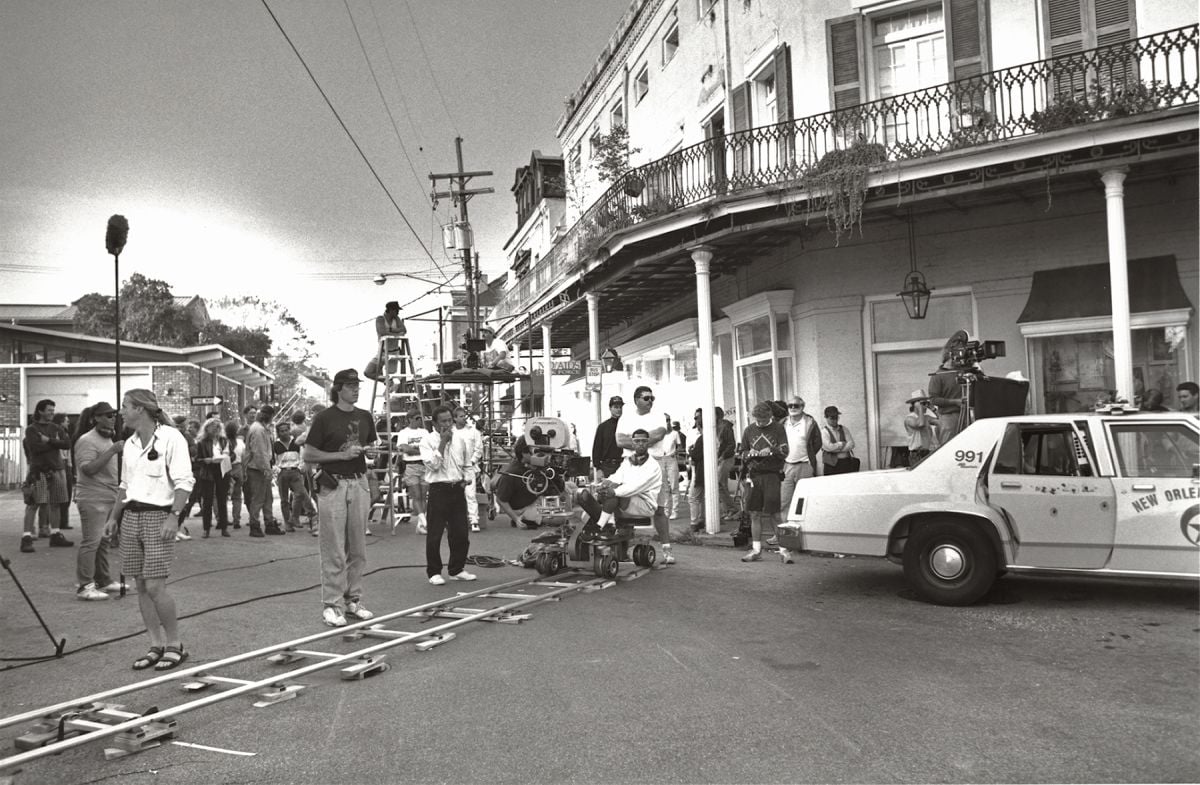

During these formative years, colleagues Carpenter had worked with in Orange County were also coming up to L.A., and some who found work at companies that produced features would help Carpenter land interviews for “no-budget” films. “One person in particular was Daryl Kass,” Carpenter says. “He’d been a sound recordist on these documentaries I’d been involved with, and now he was learning about producing. I didn’t get most of the jobs, but it really helped me to get in front of people, and get more ‘fluid’ and relaxed in an interview situation. I’m so grateful to Daryl, because he just kept getting me into things. He introduced me to John Woo, for whom I shot Hard Target, his first picture in the United States. I also got the opportunity to shoot a cult classic, The Wizard of Speed and Time, which featured Mike Jittlov’s amazing ‘lo-fi’ stop-motion visions, utilizing humans interacting with inanimate moving objects.”

Carpenter became part of a group of cinematographers who were doing non-union work in Santa Clarita, just outside of L.A., for New Line horror films. “Nightmare on Elm Street films were pretty much their big-ticket franchise,” he says. “There were a lot of these kinds of movies. They might not have been great, but they gave some of us a canvas to paint on. After shooting additional photography for New Line, I later shot the low-budget comedy-horror pic Critters 2 with horror master Mick Garris,” another job Carpenter credits Kass with helping him land.

A further opportunity soon arose, whose benefits wouldn’t be clear for some time. “You never know what’s going to be the best thing for you,” Carpenter opines. “I did a film called Solar Crisis, which had Japanese funding and turned out to be a science-fiction film that didn’t work — in every way possible. But I thought it looked pretty good. So when it became apparent that it wasn’t going to be released in theaters, I gathered all the material I could, and I went back and re-timed and re-transferred it so I had something to show. I called it a $20-million sample reel.”

Some time later, while shooting Pet Sematary II — “with the delightful director Mary Lambert,” Carpenter notes — that film’s co-star Edward Furlong, who was fresh off Terminator 2: Judgment Day, helped in connecting Carpenter with Cameron, who at the time was looking to shoot a low-budget, non-union feature — when Carpenter still wasn’t yet a member of the local. Fortunately, Carpenter had his reel to show. Though Cameron’s project fell through, the director later brought him on board to photograph the far larger project, True Lies, which was already being discussed in the trades for its proposed size and scope. “It didn’t compute at first,” Carpenter says. “I felt like, ‘That would be three big steps forward. No, I don’t see that happening.’”

Though Cameron himself isn’t sure what specifically clinched his decision, the director notes, “I remember liking his nights. Some cinematographers say nights need to be dark. I believe you use cues like color temperature to show that it’s night, but you open it up and see into the shadows. That was Russ’ instinct as well. I looked at some of his films and saw a lot of nice photography, and it just made sense.”

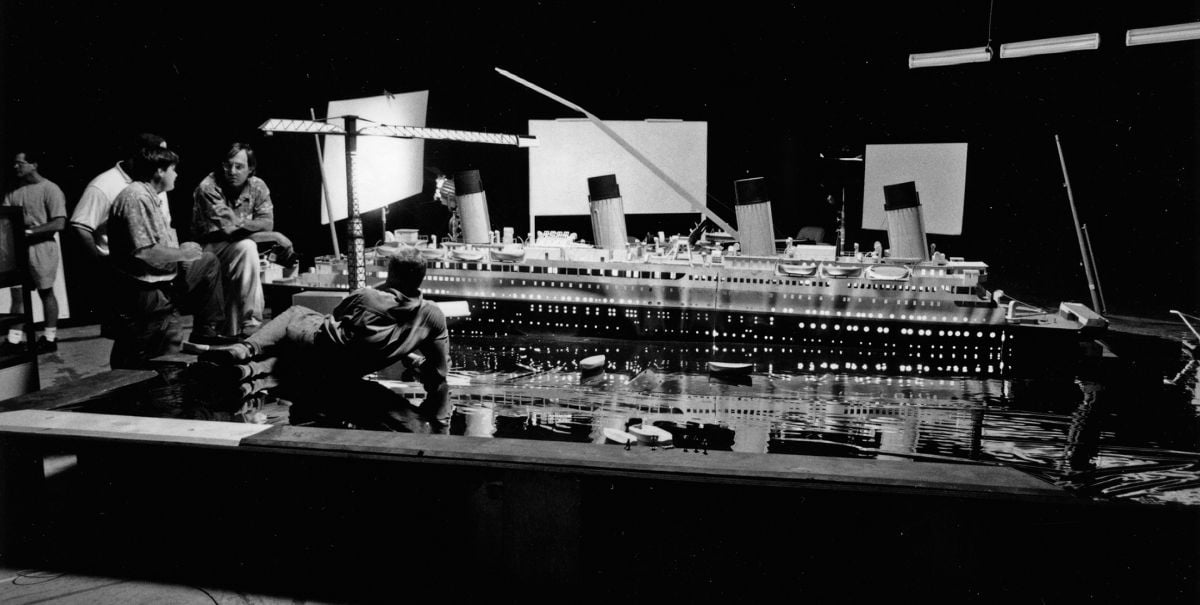

Cameron also speaks highly of Carpenter’s instinct for careful planning. “He’s very collaborative and very meticulous in terms of testing,” says Cameron. The director recalls the cinematographer’s diligent work “figuring out filters and stock. On Titanic, we decided that every white [light] would have Half CTO gel on it, so the blue would be richer when we timed it back to white. We didn’t know that would be such an important aspect of the look until we tested a lot of things and discovered that together.” Regarding the duo’s next collaboration, Avatar 2 — for which Cameron and Carpenter are preparing at the time of this writing — Cameron relates, “These days, he’s testing to create excellent LUTs.”

Carpenter makes special note of the value he places on collaboration with his crews. “I always look at the massive number of people on my crews who help and enable me, and who have stopped me from doing something maybe a little idiotic with some lighting idea that I had, and who helped me come up with a more sensible way of achieving my vision. I can’t imagine having received the Oscar for Titanic without my gaffer, John Buckley. He had such a formidable job. That set looked like a ship from the outside, but when you walked around the wall to the other side, it was miles and miles of cables, and thousands of lights. And another gaffer/artist who’s been so essential to my process, Len Levine, is somebody I’ve been working with since the Eighties. He’s a marvelous human being and a godsend.”

Says Levine of working on a dozen or so features with Carpenter, “He loves his job. He loves light.” Levine adds that Carpenter is always emotionally invested in the image. “He goes through the highest highs and lowest lows of anybody, depending on what he’s looking at.”

Carpenter has shot quite a few big-budget features, including Ant-Man (AC Aug. ’15) and The Indian in the Cupboard (AC Aug. ’95) — both of which offered the challenge of creating miniaturized protagonists — as well as two Charlie’s Angels movies and xXx: Return of Xander Cage, but he still keeps a hand in the indie world. “I did a film in India called Parched,” he says. “By American standards it was made for a buck-fifty, but it really took me back to the original joy of filmmaking. I had such a wonderful experience working with the Hindu and Muslim film crew. I loved being able to make a film in a more hands-on way; I hadn’t operated in a long time. [I worked with] a wonderful Indian director, Leena Yadav, who has such a beautiful soul and presence on the set. It’s probably the most ‘Russell’ film that I’d shot in a long time.”

Carpenter is eager to get started on the new Avatar film, which will combine live action with motion-capture characters on virtual sets, the latter of which he will light virtually. Comfortable embracing new technologies and looking forward to further expanding his filmography, the cinematographer is not one to lament how things were done in the “old days” — though the announcement of his award has given him cause to reflect. “I can still see that passionate person who was working on those early films,” he says. “It could have been Critters 2 or even the earlier things I did, and when I look back, I think, ‘There was a person who was passionate about film!’ And I still see that in myself.”

Cameron observes, “You see the twinkle in his eye when he sees something he likes. That’s what you want — a cinematographer who shows up excited every day because he wants to make something look beautiful, or stark, or whatever it is the story calls for.”

Carpenter will receive the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award on February 17 during the 32nd annual ASC Awards for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography.

You can listen to Carpenter discuss his work on Titanic in a recent edition of the AC Podcast.

UPDATE: Watch Carpenter's complete ASC Awards presentation video here.