A Rearview Look at Shooting 8 Mile

Twenty years on, Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC remembers his collaboration with director Curtis Hanson and rap artist Eminem on this breakthrough hit.

“It just felt like something very alien to me and very interesting to explore,” Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC says about 8 Mile, which recently celebrated the 20th anniversary of its release in November of 2002. Early that same year, the Mexican cinematographer was hot off his collaboration with Alejandro Gonzales Iñárritu on Amores Perros (2001) and had just wrapped shooting Julie Taymor’s biographical drama Frida (2002) when he got a call. It was director Curtis Hanson with a proposal for a film depicting the early life of breakout Detroit rapper Eminem — eventually to become known as 8 Mile.

“The idea was very interesting to me,” Prieto reflects, “Because, certainly, I had no clue of the world of hip hop and never been to Detroit, or Michigan for that matter.” However, Hanson was taking his time bringing the cinematographer onto the project. After a few more inconclusive conversations between him and Prieto, Hanson admitted that he was nervous about the cinematographer’s previous two films, both of which had a very “polished” look. Seeking the naturalism of Amores Perros, Hanson feared the aesthetic he sought was more the influence of Inarritu’s direction than Prieto’s creative instincts. To this, Prieto responded, “Listen, I'll do the style that's appropriate for a movie… I’ll do the director’s film and I wouldn’t do something polished for a story like 8 Mile where the characters live in a trailer park.” Hanson soon hired Prieto and they began preparations.

During that time, Hanson gave Prieto a key metaphor: “I'd like this movie to look like a weed growing in the crack of a sidewalk.”

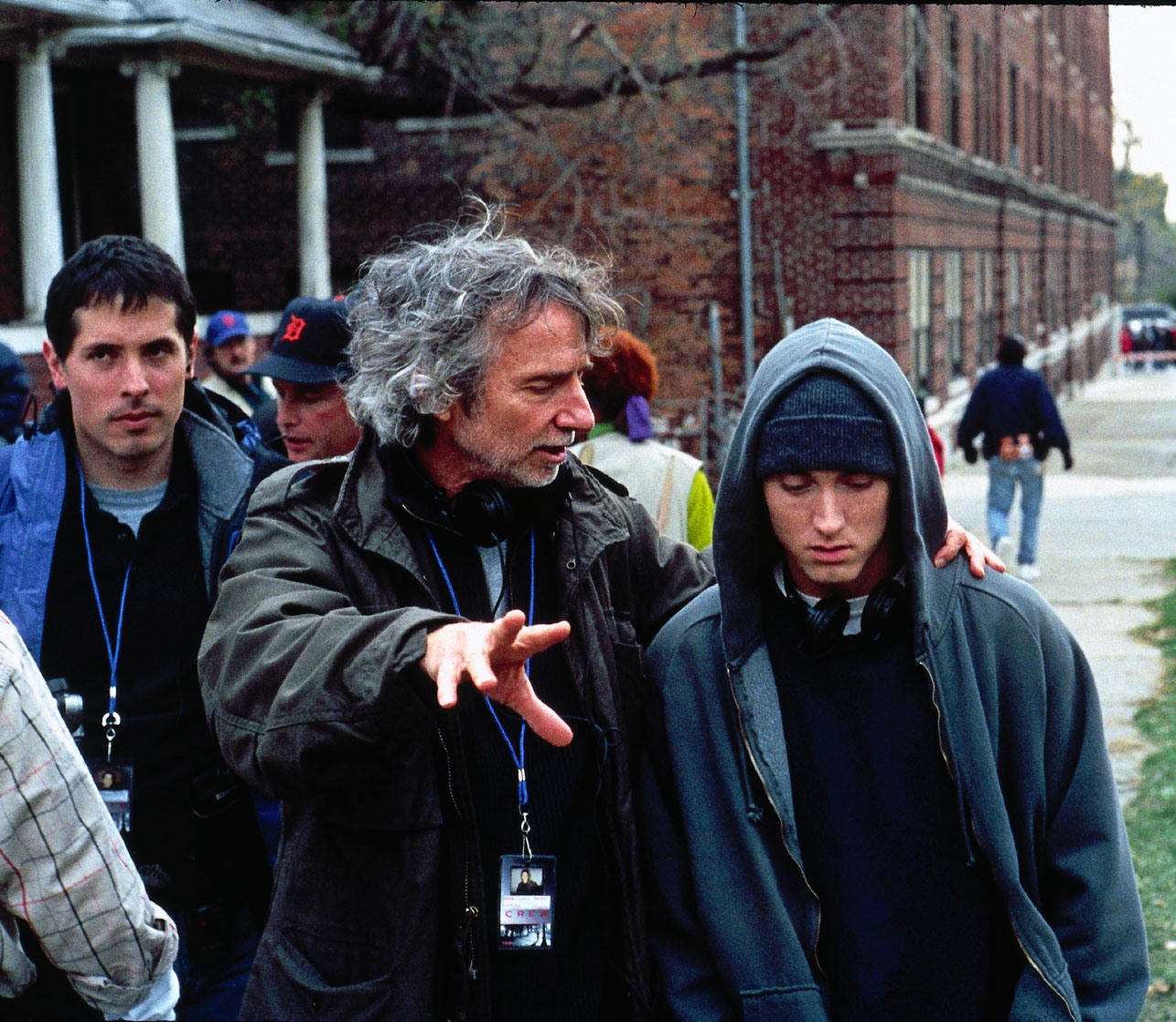

“Many times, Curtis [Hanson] would turn to me and say, ‘Okay what do we do first?’ So that, for me, was exhilarating because it meant we were designing the language of the camera right then.”

— Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC

With two months of prep time in Detroit, Prieto got to work finding this visual approach. “I thought it was interesting that a Mexican cinematographer would be picked to do a movie about hip hop and Detroit,” he remembers. “So, I brought in my own culture and influences from growing up.”

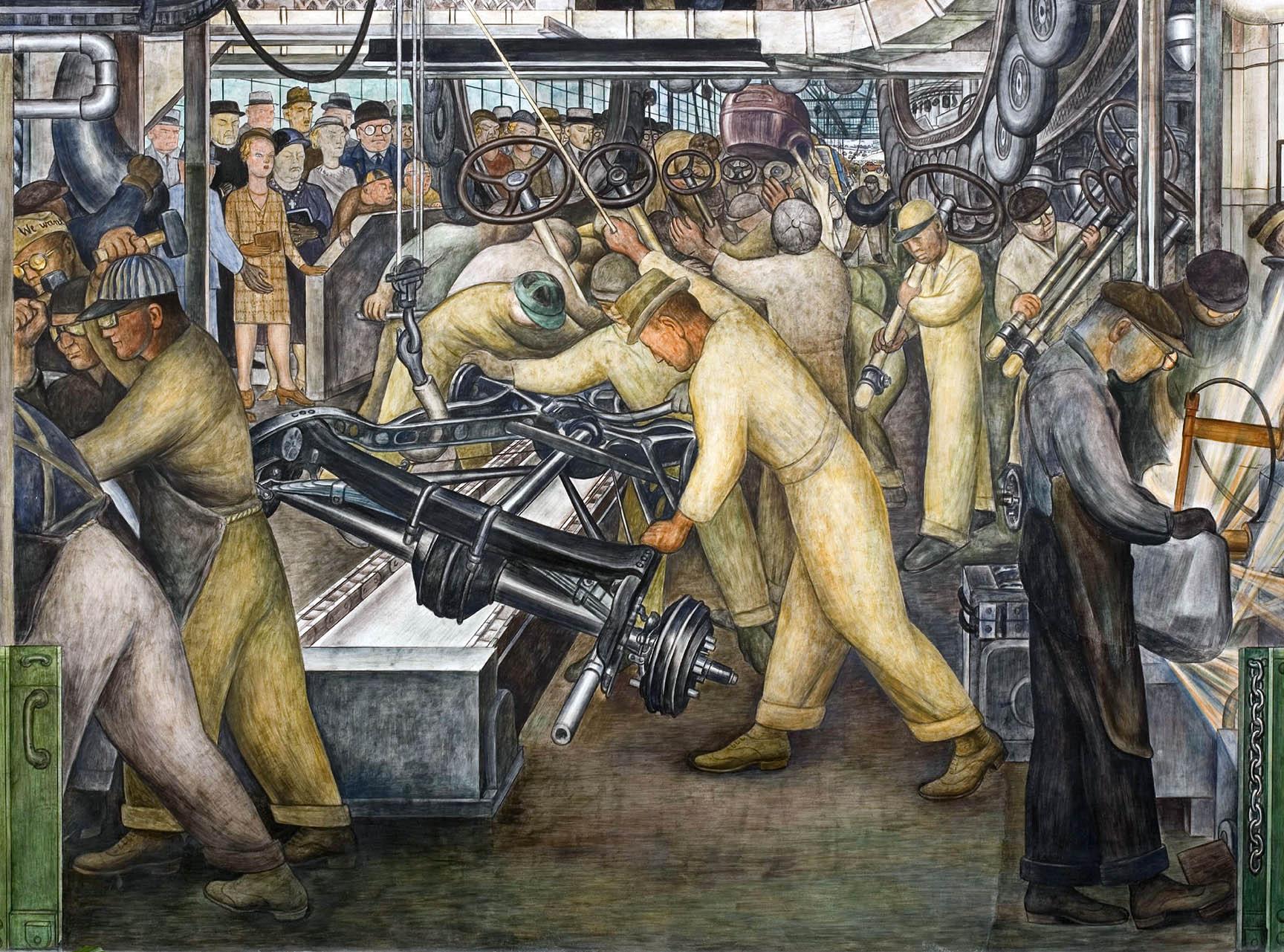

One of the first places Prieto visited upon arrival was Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry murals (1932-’33) at the Detroit Institute of Arts. He was enamored with the color palette which the famed Mexican artist chose to portray the city.

“The colors that Rivera used were metallic gray, hues of green, and then the contrasting orange of sparks, fire, and molten metal. So I used that color combination throughout the film.” Prieto explains that he emulated Rivera’s green-cyan by using tungsten-balanced film stock, fluorescent lights and Lee 728 gels, while the orange was accomplished with mostly incandescent practicals and sodium vapor street lights. Prieto drew inspiration for his use of practicals from still photographer Nan Goldin — who was also an influence on Amores Perros.

After two months of prep, Eminem arrived and the production began shooting. “I was very impressed with Eminem,” Prieto recalls about the first-time actor who played the lead role of Rabbit — a thinly veiled version of himself. “I kept imagining that this arrogant young rapper was going to show up with his posse and always be late. I was mentally preparing for that. But none of the above — he was very professional, arrived on time, and knew his lines every day. He was really excellent, and took it very seriously.” Prieto laughs and adds, “I read somewhere that Eminem kind of lost interest in acting because of that experience. Every day was so long, and it was very tiresome. Curtis would do a lot of takes, but that's just him as a director — he wanted to try different things and get a lot of coverage.”

The crew took an improvisational approach to the film, which added to the long days. Prieto recalls, “I kept wanting to sit down with Curtis and create a shot list as I've done before with many other directors, including Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu… [but] he finally told me, ‘Listen, we're not going to shot list. I want to approach this movie the way the rappers approach their battles: they have a sense of what it is… and then just feel it and improvise.’”

Prieto found the spontaneous approach an exciting artistic experience. “Many times, Curtis would turn to me and say, ‘Okay what do we do first?’ So that, for me, was exhilarating because it meant we were designing the language of the camera right then. I had a lot of input on the angles, lenses, and, as the scene was unfolding, I would operate the camera according to what the moment felt like.”

“It was [however] complicated to light,” Prieto adds, “Because I had to design lighting that would allow me to shoot in almost any direction and instantly pan around to find something while not having stands and flags in the way.”

“I guess there’s a certain innocence that I remember: of me being in Detroit, being in the presence of all these artists and rappers, [not understanding] the way they speak, the words they’d say…”

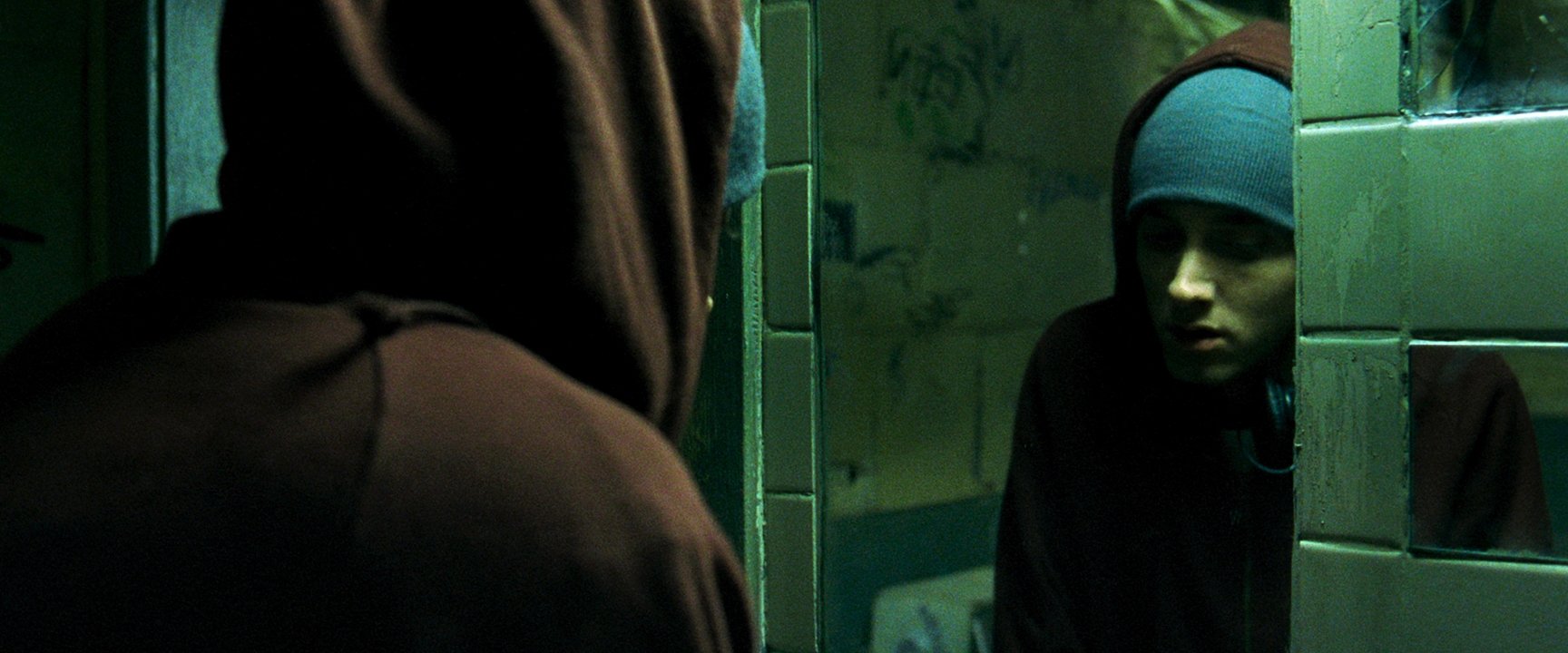

The cinematographer recalls one of the most famous scenes of the movie in which the improvisational camera approach really came to fruition: the final rap battle between Rabbit and Papa Doc (Anthony Mackie). As Prieto recalls, “The crew never heard what they [the rappers] were going to say beforehand. Even though they did prepare and [pre]write the battles, we didn't know what it was going to be.” The battle scene was shot handheld with Prieto operating. Rows of Kino Flos with cool white fluorescent bulbs backlit the crowd and a harsh spotlight illuminated the performers on stage. Prieto is opposed to shooting handheld for simply a “documentary” feeling, but instead uses it as a tool to follow the rhythm of the scene — of which there was no lack during the rap battle.

“In that climactic scene, I was just following the feeling,” Prieto recollects with a chuckle, “Also, I didn't quite understand what they were saying — bearing in mind I'm Mexican and with the hip hop language and rhythm as they say it… I wasn't like, ‘Whoa, you just said this.’” Prieto pauses, “I could just feel the energy of what he was saying. It felt like playing a musical instrument. Like I was part of a show. It was a dance between the rappers and myself with a camera — feeling the energy and just moving the camera accordingly.”

Looking back on the experience of making 8 Mile, Prieto thinks of the word innocence. “I guess there's a certain innocence that I remember: of me being in Detroit, being in the presence of all these artists and rappers, [not understanding] the way they speak, the words they'd say… I felt sometimes silly and out of place, but they were very warm. They were all really open to me learning.”

Prieto ascribes the word innocence to the story as well — a theme he has carried with him throughout his own life. “The film has a sort of gritty, naturalistic feel to it, yes, but there's also an innocence to the story that I still love,” he reflects. “It's just coming-of-age: being with your friends, becoming a man, learning what that means, appreciating loyalty — and all these things that are quite beautiful, but the word that comes to mind is innocence. And it's something that I appreciate in the film that I try to keep for myself. I try to approach every project that way.”

Since 8 Mile, the cinematographer has worked on some of the biggest films of the 21st century of abundant styles, directors, and cultures. His filmography now includes Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain, Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street, and Greta Gerwig’s yet-to-be-released Barbie. In all his films, Prieto keeps a similar sort of innocence that he experienced in 8 Mile while exploring subjects and characters completely unfamiliar to him. “That's something that's wonderful in our industry,” Prieto concludes, “That you really get to be a child. Every time. That's what I strive for.”