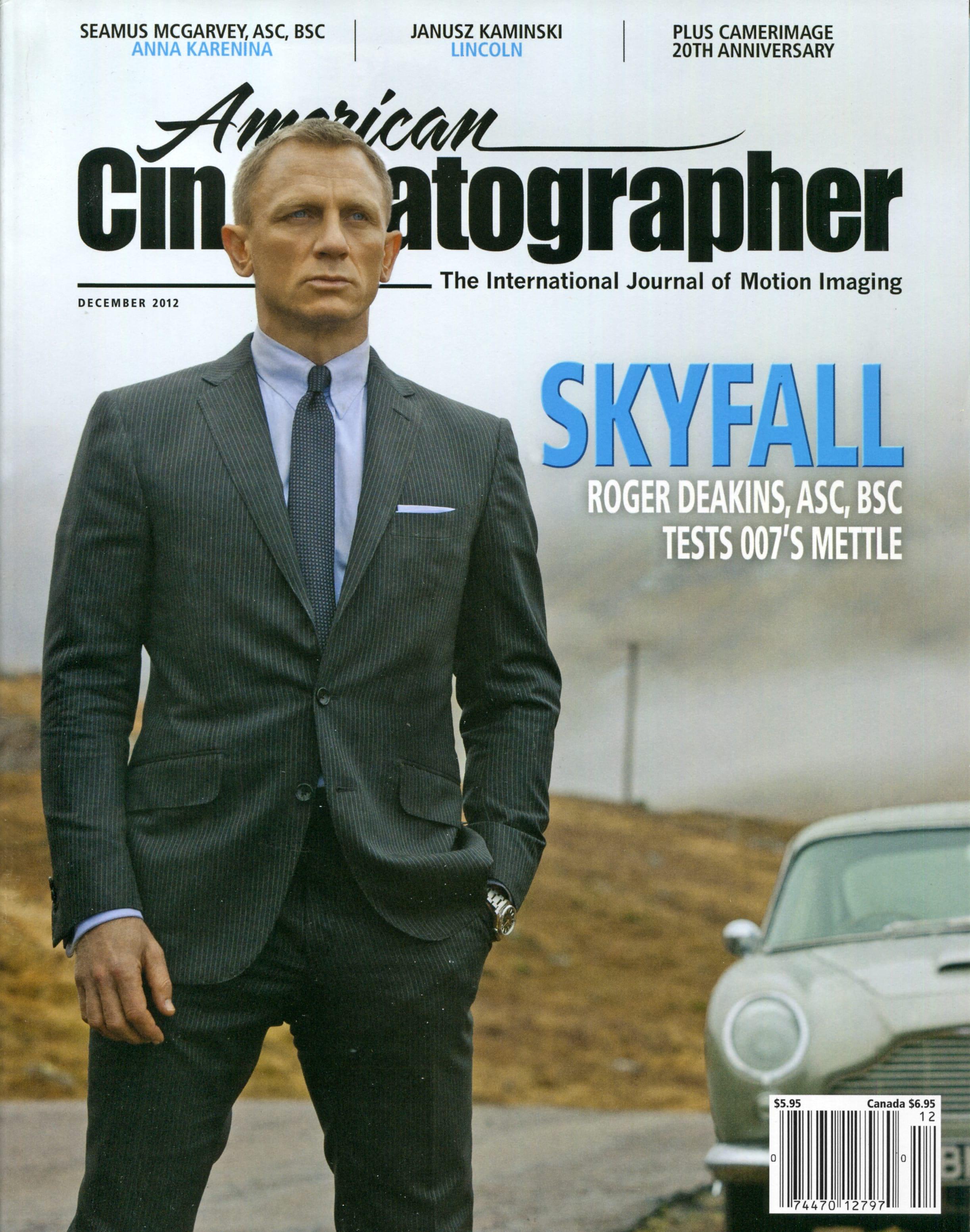

Skyfall: MI6 Under Siege

Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC joins Her Majesty’s secret service with the 23rd James Bond adventure.

Unit photography by Francois Duhamel, SMPSP, and Jasin Boland. Images courtesy of Sony Pictures.

British secret agent James Bond (Daniel Craig) returns to the big screen in Skyfall, which reteams director Sam Mendes and cinematographer Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC, and is the first film in the franchise to be shot digitally. Although the action-packed picture is a departure from Mendes and Deakins’ previous collaborations, Jarhead (AC Nov. ’05) and Revolutionary Road (AC Jan. ’09), the director says their prep was similar in many respects. “I told Roger that although Skyfall was much bigger and had an action element that we hadn’t really tackled before, in every other regard, it would be like working on any movie with me,” says Mendes. “I would want from him exactly what I always have, which is an immense involvement in prep, and to be my chief collaborator on set.”

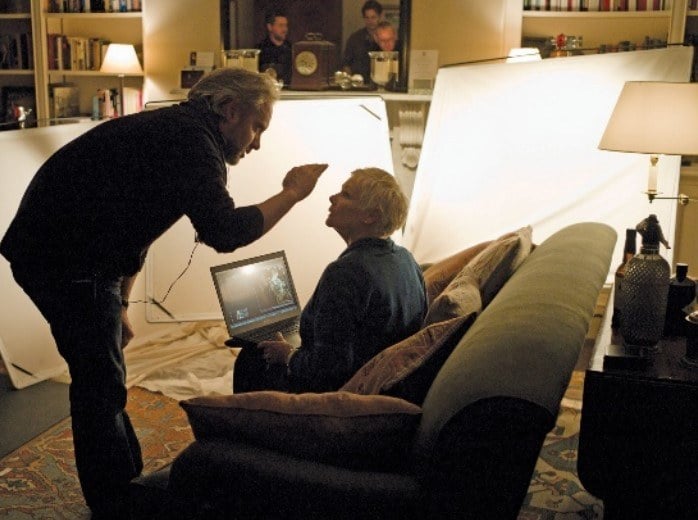

Deakins recalls that during his long prep with Mendes, “we went through the script together, talking not just about the visuals but also about character development. It was great to be involved in that interchange of ideas because those discussions affected how the script developed.”

Having not made a film in England since The Secret Garden (1993), Deakins enjoyed the opportunity to work with some colleagues from his past, including gaffer John “Biggles” Higgins, with whom he shot more than a dozen films in the 1980s and 1990s. “It was a real treat to get back together with Roger again, and it felt like we were just carrying on from where we left off,” says Higgins. “Some of the technology and the methods had changed, of course, but the cooperation was the same.”

Deakins brought three key crewmembers with him from the States: 1st AC Andy Harris, dolly grip Bruce Hamme and digital-imaging technician Joshua Gollish. “Because I operate, my camera team is really important, and Andy and Bruce are crucial to the way I work,” he says. “They set up the camera while I’m lighting so I can just walk on and do a shot.” He had previously collaborated with Gollish on In Time (AC Nov. ’11), his first digital feature.

Mendes had not yet worked with digital capture, however, and he acknowledges that he “was initially very suspicious because I’m a big fan of film.” Deakins believed shooting Skyfall digitally would be beneficial at a number of the locations being discussed, and he showed Mendes some tests from In Time, which he had shot with the Arri Alexa Plus. “I was very impressed, so we shot our own tests, and I continued to be impressed,” Mendes recalls.

Since shooting In Time, Deakins had maintained a dialogue with Arri, expressing his desire for a version of the Alexa that had an optical viewfinder. His request was fulfilled with the Alexa Studio, which Arri rushed into production to be ready for Skyfall, and which has the same rotating-mirror shutter and optical viewfinder as the Arri 535B that Deakins has used for many years. “That was a big thing for me,” says the cinematographer. “Of course, the mirror shutter made the Studio heavier, so for handheld work, I tended to use the Plus, but I probably shot 70 percent of Skyfall with the Studio.”

The uncompressed ArriRaw format was also a new development for the Alexa since In Time. Deakins notes, “We were told Skyfall would get an Imax release, so how our images would look on that giant screen was a big consideration. I shot tests comparing uncompressed HD, which I used on In Time, and ArriRaw, and we blew those images up and watched them on an Imax screen at Swiss Cottage. It was quite startling; both images looked pretty damned good, but the ArriRaw had a definite advantage.”

One of the sets for which digital acquisition made a significant difference was the 67th floor of a Shanghai skyscraper, built on the 007 Stage at Pinewood Studios. The scene that takes place on this set depicts Bond stalking an assassin through the empty offices at night, with vast electronic billboards on nearby towers casting hypnotic patterns and reflections on the glass panels that separate the rooms and spaces across the entire floor. “We needed some source for this scene, and I thought using billboard hoardings outside the window to light the whole set would be the most interesting way to go, because Sam had said he wanted to capture the feel of Shanghai,” says Deakins. “Once we decided to build it as a set, Biggles and I started researching what kind of LED screens we could get to light it. We had to make sure there wasn’t too much of a moiré pattern between the pixels of the camera and the pixels of the LED screen, which would be 70 feet away.”

“We got the art department to make up a 6-by-6-foot glass panel so we could experiment by putting images from various LED sources across it to check for any problems,” explains Higgins. “Eventually, we decided to use a system called Pixled F-11 for the bigger, dominant screen. F-11 refers to the 11mm pitch of the LEDs, the gap between them. The lower the pitch number, the higher the resolution, so these were quite high resolution. For the other, smaller screen, we used a commercially available system, Pixelines, which is fairly old technology in the LED world. It’s much lower resolution, but Roger liked its quality.”

A model of the set was built to help determine angles and visual-effects requirements, with a TV monitor standing in for the large LED screen. “We needed images for the monitor, and the art department found this footage of jellyfish floating through the frame,” says Deakins. “When it came time to discuss what we really wanted to put on those screens, Sam and I looked at each other and said, ‘Well, why don’t we just leave it as jellyfish?’ It looked interesting, and it was a really deep blue, and we wanted this whole Shanghai section to feel quite cold. So that’s how the jellyfish got in the film — they were just stand-ins, really!”

Almost all of the light for the scene came from the screens, with Deakins rating the Alexa at its suggested base sensitivity of EI 800 and stopping his Arri/Zeiss Master Prime lenses down to T4-T5.6 when shooting directly at the screens, or less when shooting side-on. (Most other interiors were exposed at T2-T2.8.) Higgins notes, “If we were only seeing a quarter of the screen in shot and we wanted to maintain the exposure level, we could map that quarter electronically and take it down a stop or two without any color shift, leaving the rest of the screen running brighter to keep the ambient up. It was a very flexible system.” Deakins adds, “I did use some small LED panels off-screen to augment for closer work, but we basically shot without any other light source. That was just as well because we had a lot of shots to do in very little time.” (The LED panels used for augmentation were simply individual panels from the modular systems used for the big screens outside the windows.)

Although a good light level was achieved on the set, Deakins speculates that he would have struggled to shoot this scene on film. “Not only were there extreme ranges of contrast and color, but there was also very little light at the far side of the set from the LED panels, as there were something like 10 sheets of very thick glass in the way,” he says. “That was a situation where seeing the exact image I was shooting and knowing exactly where my exposure was in terms of the contrast of the image on the LED screen was a real advantage. For me, the difference with digital is the comfort factor of seeing it and the freedom to push it further than I might on film. That Shanghai set made me realize we’d made the right choice of format. It was one of the first things we shot and was quite complicated, so it was a relief when we managed to get through 12 setups and it all looked pretty good.”

For this sequence and many others in Skyfall, Deakins made use of a Power-Pod remote head mounted on an Aerocrane jib arm, a technique he has often used in the past. In fact, much of his camerawork followed the approach he and Mendes had developed on their previous collaborations: a mix of careful planning and spontaneity. “It stays the same — it’s not about the scale of the movie,” says Deakins. “On Jarhead, Sam said to me one day, ‘Here we are, doing a $70 million picture with all these stunts and explosions, and you’re shooting with a handheld Arri 3-C!’ It was the same on Skyfall. Some days, [B-camera operator] Pete Cavaciuti and I would both have handheld cameras on these big stunts. That’s the way Sam and I like to work; we both enjoy being quite instinctive on the day.”

Big action scenes, such as a train crashing through the roof of an underground bunker, required multiple camera positions, but in general, the number of cameras was kept to a minimum. Deakins notes, “It varied from day-to-day and depended on the scene, but it wasn’t like we had to do everything with five cameras just because it’s a Bond movie. Sam likes to have the main cameras focused on the characters and the dialogue. Sometimes we’d add other cameras to get little pieces, and, of course, with all the complex action sequences, we did use additional units. Both [2nd-unit director of photography] Alexander Witt and [splinter-unit director of photography] Peter Talbot shot some fantastic footage.”

The visual effects team also used Alexas. “Because he had no experience with digital capture, Steve Begg, our visual-effects supervisor, did some very comprehensive tests in prep with a number of film formats, as well as another brand of digital camera, in all sorts of situations where the dynamic range of the camera was key,” Deakins notes. “Steve did some fantastic work on the film both with models and CG comps.”

The cold look developed for the Shanghai skyscraper contrasts with a view Bond gets of a room in a neighboring hotel, which is suffused with yellow and stands out like a box of light in a cold environment. “Color was very important throughout the shoot,” says Deakins. “We tried to shoot London exteriors in overcast conditions, though that wasn’t always possible. In the story, MI6 is driven underground into bunkers beneath the city, and there we used harsh fluorescent lighting and a monochromatic feel. When we cut from that to Shanghai, we punch into this futuristic world, and then, for the casino in Macau, the idea was to go back to an older, more mysterious world, so we chose red and gold. Each color palette was designed in the context of the others.”

The waterfront Macau casino was also a set built at Pinewood Studios. The sequence begins with an exterior shot of Bond approaching the casino on a small boat, surrounded by hundreds of floating lanterns and navigating through illuminated arches in the shape of dragons’ heads. “We shot that on the Paddock Tank at Pinewood,” says Deakins. “We wanted some sort of boom arm to track behind the boat, but we had to get back from the edge of the tank in order to make the most of the space. My grip suggested a 100-foot SuperTechnocrane, and that allowed us to do the tracking shots, get the very high angles we needed, and work very quickly. I think it was the first time that particular crane had been used in England, and just about every grip in the country came out to see it!”

The dragons’ heads provided the strongest light source, while the floating lamps were dimmed-down 100-watt fixtures. Higgins explains, “The wiring was underwater, and for safety reasons, we had to find bulbs that would run at a low voltage. We used 24-volt fixtures that ran off a power supply rather than batteries, and we gave them a bit of flicker. They had stabilizers hanging down from them, so we didn’t need anyone in the water. We were lucky it was a calm night, because a strong wind would have caused real problems! In the background, the entire outline of the casino was lit with thousands of 60-watt golf-ball fixtures on dimmers. That was a massive rigging job for my practical team.”

Once Bond enters the casino, the camera follows him around in an extended Steadicam shot, which largely dictated the lighting design. “You see the whole set in that one shot, so we had nowhere to put normal movie lights,” continues Higgins. “Roger fought to get a two-day pre-light, and we rigged various kinds of practicals. We had a workshop at Pinewood, and whatever the art department designed went through there. Every practical in the movie was modified or made on site.”

“We rigged about 260 practical lights, and most of them held a heavily dimmed 1K bulb,” Deakins elaborates. “Another part of the set was lit by about 100 double-wick candles that had to be replaced every 10 minutes. Over the gaming tables, we modified some big overhead lanterns by lining the shades with a gold stipple reflector and putting in 2K bulbs, which were dimmed, to bounce off the gold and create warm, glowing light over the tables. For the sequence in the bar, we did a big, gold bounce rig, which was the most complimentary way to light faces. We used a number of different techniques.”

The set had the appearance of being entirely lit by practicals, but Deakins’ crew did rig other lights for closer work. “In the center of the main gambling area, we had a 20-foot circle of 2K Blondes on a truss that could be lowered to give a soft, gentle light, with the Blondes dimmed to about 20 percent,” says the cinematographer. “We also had well over 200 300-watt Fresnel lamps on scaffold pipes that we could drop down to get the light at 45 degrees to the actors.” Higgins adds, “The poles varied between 6 feet and 20 feet long, with multiples of six Arri 300s, going up to 18 on some of them. We used multiples of six because the dimmer packs output in six channels, so a single cable from the dimmer could deliver six circuits.”

For Mendes, the lighting of the casino set was a good example of how digital capture benefited the production. “The way Roger lit that set, with all those practicals, was extraordinary, and there’s no conceivable way we could have done that on film,” he says. “That’s just one of many examples of how much flexibility the Alexa gave us without sacrificing the look of the picture for one second.”

Other aspects of digital acquisition, however, pleased Mendes far less. “With a lot of big monitors on set, there’s a slight sense of a spread of focus, which is not what I’m used to,” he observes. “There is also a certain loss of magic in the process of transformation that happens between shooting an image on film and first seeing it on the big screen. It gives you a huge lift to see what you shot the previous day projected large, if it has been properly timed. On Skyfall, it was the other way around, because we could look at the image on a very good monitor on set and see it exactly as Roger intended, and when we saw dailies the next day, they were lower-resolution images and wouldn’t look quite as good. So there wasn’t that wonderful sense of surprise.”

During the shoot, ArriRaw files were recorded to Codex recorders via a T-link connection. Concurrently, ProRes 4:4:4:4 files were recorded in Log C format to in-camera SxS Pro cards (purely for backup in case of emergency). Then Avid Media files were derived from the original ArriRaw material — along with all metadata — for dailies and editorial work. After the film's editing was completed, the ArriRaw files (with the metadata) would be conformed in sequence for the final digital grade.

This all formed part of a workflow provided by EC3, a collaborative entity that allows Deluxe facilities EFilm and Company 3 to combine resources and offer services to productions on location as well as in post. For Skyfall’s final grade, Deakins worked with two colorists, Mitch Paulson of EFilm in Hollywood and Adam Glasman of Company 3 in London.

From a photographic standpoint, some of the most complicated scenes in Skyfall appear in the major action sequence that serves as the movie’s climax, which takes place on the Scottish moors. Deakins explains, “It involves interior and exterior scenes of a mansion and, later, a chapel, and it goes from daytime to dusk to night. The nightwork involves explosions, a spotlight from a helicopter, and a firelit chase across the moors. It’s an extended sequence of light change, and we were shooting the various elements on very different days. Take that dawn scene in No Country for Old Men [AC Oct. ’07] and multiply it by 50 — that’s how difficult it was!

“The hardest thing was the interior of the mansion, which we built on stage at Pinewood, because of the changes to the light coming in from outside,” he continues. “On that set, I used bounced HMIs outside the windows and almost nothing inside. We started off with white bounce and then went to a blue bounce material, and then we took the blue away and just used black drapes around the set to build up the feeling of the light dying. We even started filtering the HMIs, and eventually, we got up to Full plus Half CTB to get that deep twilight before we went into complete darkness.”

Once darkness fell, Deakins had to create the effect of a helicopter searchlight shining through the windows and following Bond around the space inside. He notes, “We created a big trackway on the ceiling outside the set, a computer-controlled lighting rig that would zip a 6K Par around the house.” The movement of this searchlight had to match between the interior on stage and the exterior on location. “On our location ‘set,’ we shot some of the scene with a real helicopter mounted with a Midnight Sun,” says Deakins. “We did some closer work with a 6K Par that was mounted to a camera remote head on a tower crane, and which was controlled by a camera operator with the help of a witness camera.”

The chase across the moors was filmed inside the largest stage at Longcross Studios, just west of London. At this point in the story, the mansion has caught fire, and the action had to look as if it was being lit by the flames in the deep background. Higgins explains, “We built a tapered rig of 32 Dinos gelled with ¾ and ½ CTO, using each Dino bulb like a pixel on an LED screen, so we could program in images of fire and the lamps would mimic it. Roger had us make this rig very hot in the middle and then fading out toward the edge. We started running the Dinos at up to 80 percent, with the flicker, and then as the fire goes out, we dropped that off. We also filled the set with smoke because the weather was meant to be foggy. The effect was very eerie.”

“The idea was to use the Dinos to make the smoke filling the stage look like it was lit quite naturalistically by fire sources, and then replace the Dinos with CG fire in post,” adds Deakins. “We did much the same thing for the oil fires in Jarhead.”

Summing up his latest collaboration with Deakins, Mendes observes, “I think we probably had more fun on this movie than on any we have done together in the past, even though it’s been the hardest work and the largest scale. I think we were able to use the resources of a Bond movie to achieve things that are simply not possible on a smaller budget.

“Shooting digitally is a different rhythm of work, but, in the end, it’s just a choice,” he continues. “Can I imagine shooting a movie on film again with Roger? Yes. Would there be moments where I thought, ‘This wouldn’t have happened with digital’? Yes, there would be. I will certainly shoot movies on film again, but perhaps not a movie of this scale.”

2.40:1 and 1.90:1 Imax

Digital Capture

Arri Alexa Studio, Plus, M

Arri/Zeiss Master Primes

Deakins earned ASC and Academy Award nominations for his outstanding work in the film, among many other honors. And 2nd-unit cinematographer Alexander Witt was later invited to become a member of the ASC.