Smile 2: Lighting a Pop Star’s Meltdown

“One of the most important things about being a cinematographer is surrounding yourself with people who know more than you, and then asking them for help.”

Unit stills by Barbara Nitke. All images courtesy of Paramount Pictures.

When a horror film does well, sometimes the sequel will just “rinse and repeat” — the filmmakers do the same thing and hope for the same result. But director Parker Finn and I wanted to make Smile 2 only if we could push ourselves and push the film into a different space, and I hope we did that. Whereas on the first film we were getting to know each other and discussing our tastes and sensibilities, this time there was a helpful shorthand, and we just jumped in.

The movie is centered on a pop star named Skye Riley (Naomi Scott), so Parker shared some musical elements with me, obtained from some music producers who had existing samples or who had created some pieces specifically for Smile. Our composer, Cristóbal Tapia de Veer, was also involved very early in prep. This really helped me understand what tone Parker was going for, and it helped us create a visual language.

We also looked at films about performers under pressure, such as Black Swan (shot by Matthew Libatique, ASC, LPS; AC Dec. ’10). Visually, that film is very different than ours, but what Natalie Portman’s character goes through is comparable to Skye’s situation: She has vivid hallucinations, and her world is unraveling while all eyes are on her. For similar reasons, we also watched the 2018 remake of Suspiria (shot by Sayombhu Mukdeeprom; AC Dec. ’18), Climax (shot by Benoît Debie, SBC) and Tár (shot by Florian Hoffmeister, BSC; AC Jan. ’23).

Additionally, we looked at artwork and photography. Our production designer, Lester Cohen, was adamant we do that; he’s taught me that there are many other areas from which to draw inspiration. We looked at photographs by Luc Kordas and Gregory Crewdson that evoke anxiety and loneliness, as well as the paintings of Edward Hopper.

“Many horror films live in the dark, but Parker and I like environments that don’t necessarily lend themselves to that strategy.”

We returned to the Arri Rental Alexa 65, shooting in Open Gate 6.5K. The Revenant (shot by Emmanuel Lubezki, ASC, AMC; AC Jan. ’16) showed how brilliant the camera is for shooting landscapes, and the detail is incredible. But we love it especially for portraits and how we can be on a very wide lens right in close on our protagonists. We wanted to use as much of the sensor as possible, to engulf Skye in her surroundings and to juice the anxiety. The movie is a roller-coaster ride from start to finish.

We also stayed with the 2.00:1 aspect ratio. Smile ended up getting a theatrical release through Paramount Pictures, but it was originally intended to go directly to Paramount Plus for streaming, which is why we chose 2.00:1. We feel that format is great for home viewing, but also translates nicely to cinema.

Arri Rental’s Prime DNA lenses were again our main set. The DNAs carry a 65mm lens that’s gorgeous for portraits. We often went as wide as 35mm on the portraits; the angle of view is equivalent to an 18mm in Super 35, so it’s right in the actor’s faces for a close-up.

We also carried an Arri Rental Heroes lens, which gives you a swirly effect like the Petzval. We had focus, iris and the adjustable “look” gear on a motor that we called the “director’s wheel,” and either Parker or I could control it. If your protagonist has some sort of realization, for example, you can generate the swirl within the shot and dial it in as much as you want. We used it a few times.

On the first film, we struggled to find a zoom that could carry all the way through. [In larger format,] many zooms vignette at the wide end, especially at close focus. So, I was excited when I did some testing in Burbank and Arri Rental brought out a set of three Fujinon Premista zooms that they had [expanded by a factor of 1.25] to cover the Alexa 65. The focal ranges are fantastic. We really only used the 35-125mm T3.7 zoom. Parker loves a zoom shot when it’s motivated. We employed zooms in some moments when Skye’s world turns upside down and she further loses her grasp on reality.

We also shot some 35mm film. There’s a scene in which Skye is featured on a talk show, and she’s introduced with a music video playing behind her on a TV screen. We thought, “Why not shoot the music clip on film?” I wanted it to feel a bit gritty. So, we got an Arriflex 435 with Arriflex/Zeiss Super Speed MKII lenses and shot Kodak Vision3 500T 5219 negative. It was all done on a soundstage with a Steadicam operated by Peter Vietro-Hannum. (Dan Sharnoff was our A-camera operator.) We shot the music-video footage in prep to be able to jam it into the scene, and it’s quite cool, with Skye dancing around ghosts amid strobing lights.

I used Nanlux lights a lot — they’re very handy and have come a long way. We had the Evoke 1200D and 900C for strobing effects in the music video, and for a scene involving a photo shoot with Skye trying on different outfits. There’s a visceral moment in that sequence where she’s thinking about everything that’s been going on, with all of these paparazzi cameras in her face. We used the Nanlux to mimic the strobing of the flashes.

Many horror films live in the dark, but Parker and I like environments that don’t necessarily lend themselves to that strategy. It’s an opportunity to conjure up the emotions of scary films outside of an attic, dungeon or basement. That said, we did create some jump scares coming out of shadows. Darkness is still important to us, and what you don’t see is as important as what you do.

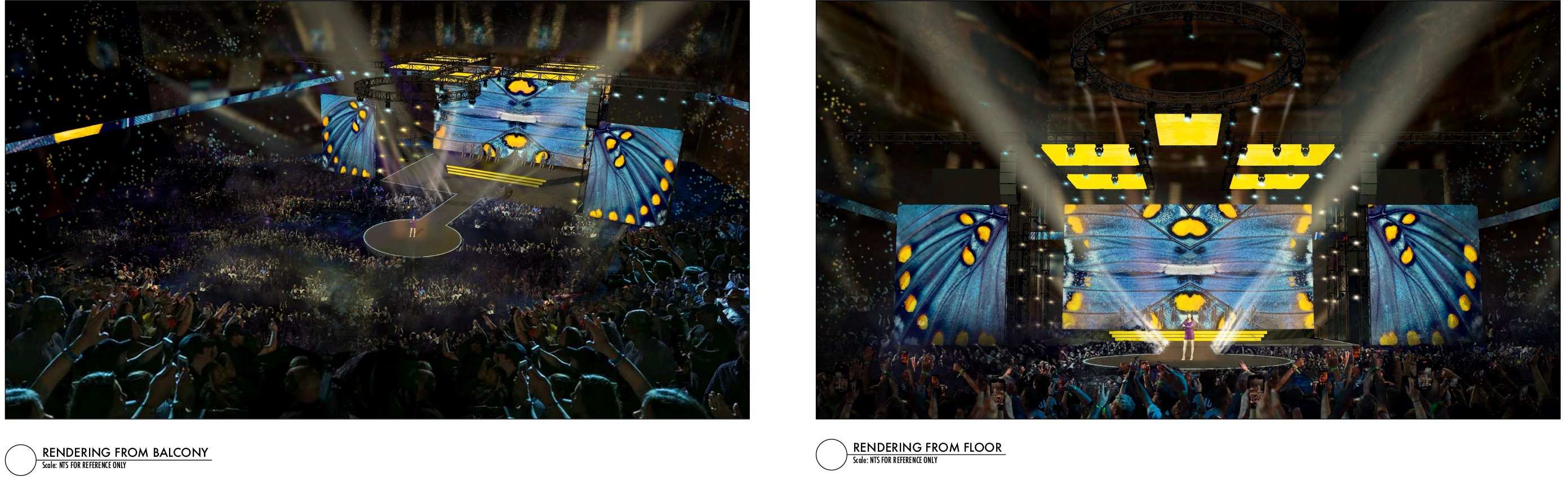

Smile is partly set in a hospital with pink walls, and it’s quite bright, yet all these horrific things happen there. Our approach is similar in the sequel, where horrific things happen in arenas with LEDs, bright lights and dancers. That juxtaposition is important to catch the audience off guard. We’re not trying to make those spaces unnaturally dark and gritty — we want things to happen in what looks like reality.

We developed a couple of LUTs with FotoKem senior colorist [and ASC associate member] Dave Cole. The movie starts with an event that takes place where Smile left off, then crosses the river into Manhattan, and we’re now in Skye’s world, where things start to look a little different. We started with the LUT from the first film and then tinkered with it, because Skye lives in a heightened, glossy world that we wanted to showcase without being too on-the-nose. We pushed certain colors and increased the halation around highlights, and I often used low-con and Radiant Soft filters. Dave also developed a LUT for scenes with a lot of blood, because there’s a lot of blood in these movies! We punched the reds a bit for gory sequences.

For our more conventional setups, I love to start with a single light source. I also love using practicals to paint the space and then movie lights to enhance, especially when you have characters walking through those spaces. I didn’t use a lot of hard lighting, because we wanted to stay in the pop-star glam space. To keep with that glossy feel, I diffused heavily. I love book lighting with a soft source. My go-tos include Creamsource Vortex8 LEDs and Arri SkyPanels. We used a lot of LiteGear LiteMats in Skye’s apartment and other locations, as well as HMIs, whether they were Arri M90s, 18Ks or smaller fixtures. We also used Astera LED tubes for close-ups and highlights.

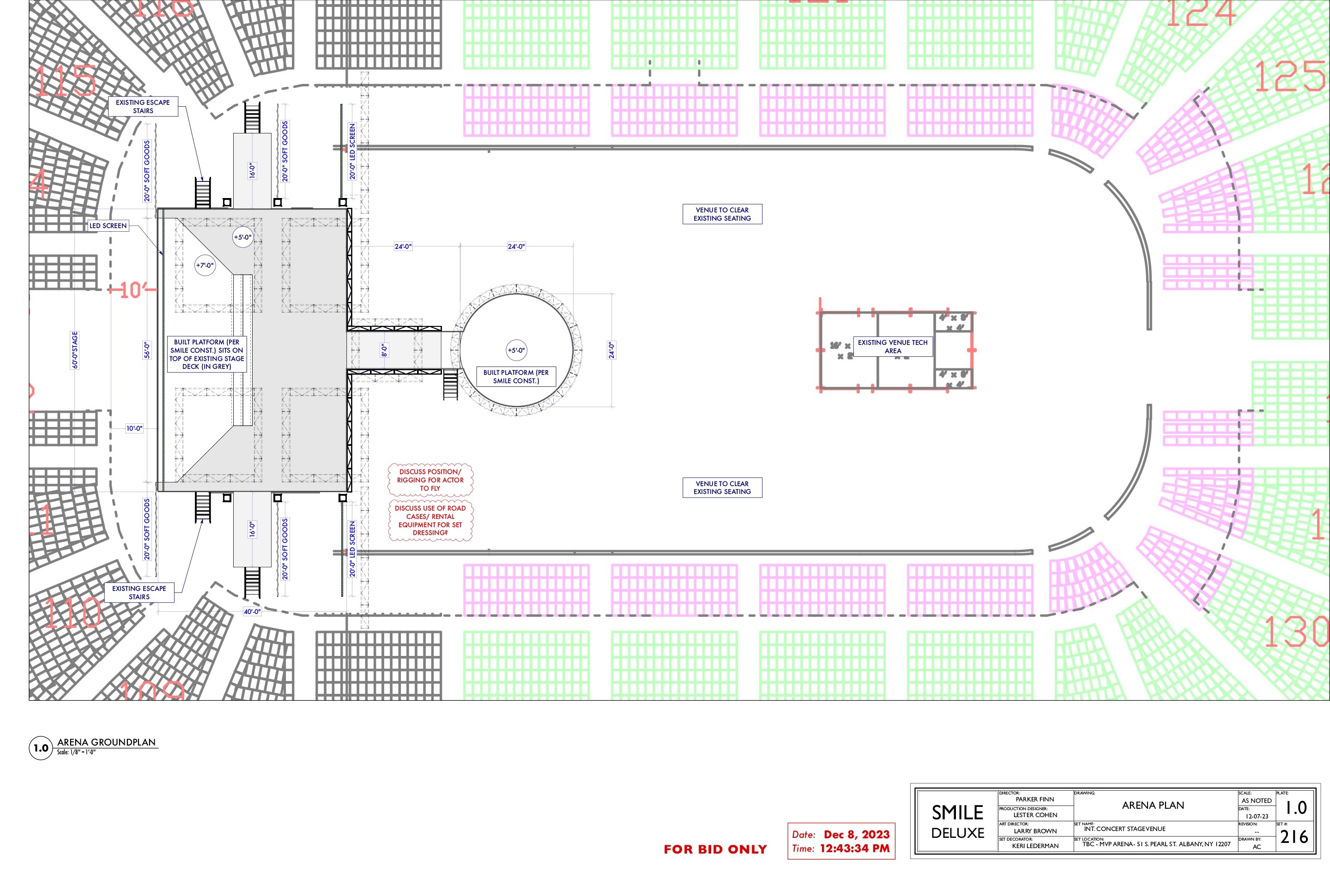

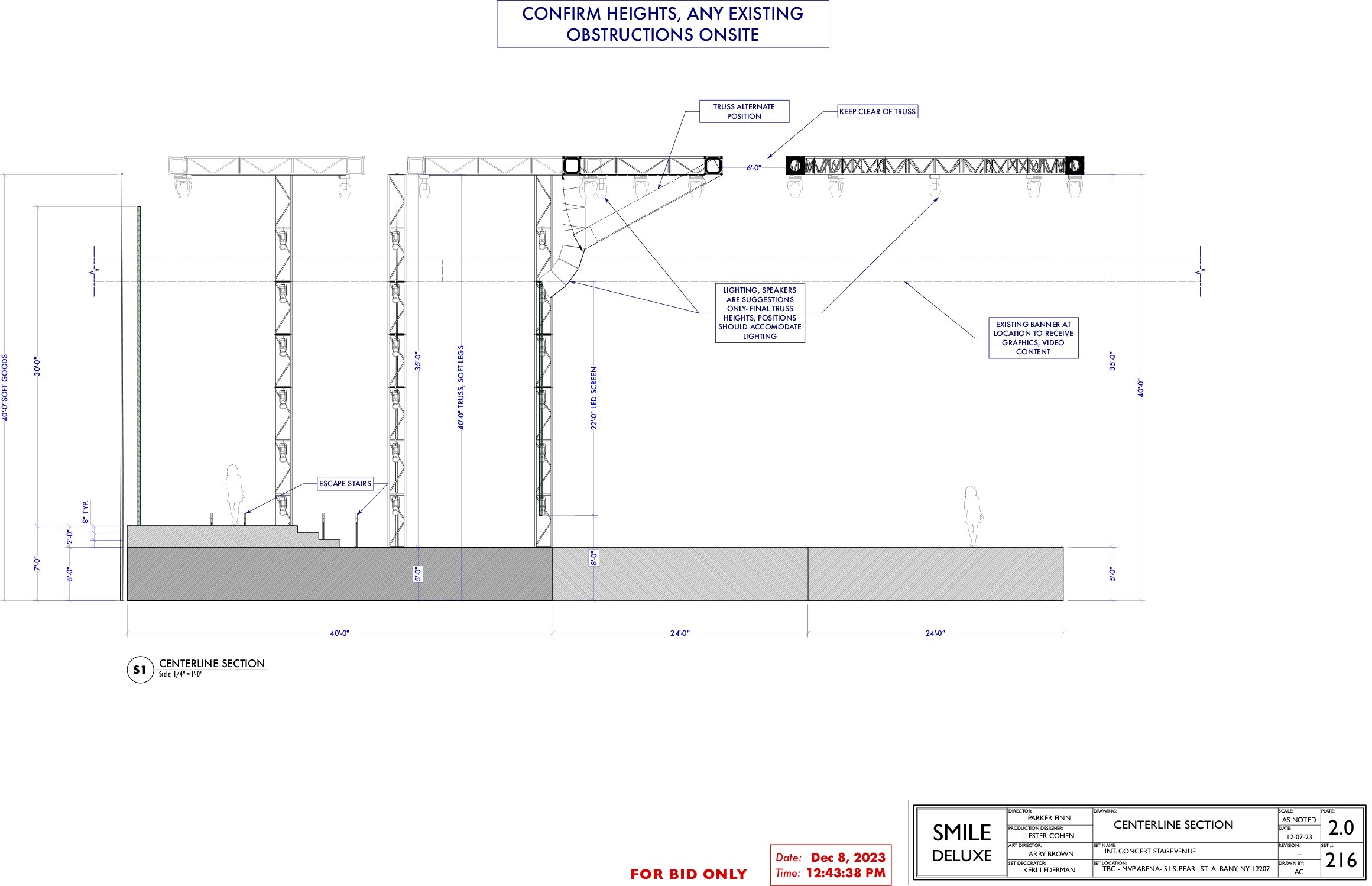

The story has a lot of musical performances, both rehearsal and concert scenes that we shot in the MVP Arena in Albany, New York. The finale was particularly complex, as we had to show 360 degrees within the 17,000-seat arena, and we had only 500 extras. We shot them in different areas, and then this material was made into plates by VFX supervisor Robert Bock from Montreal’s Rodeo FX.

I hadn’t lit stage shows before, so this caused some sleepless nights. Lights used in live concerts are different from what we use in film production. But I was fortunate to be working closely with lighting designer Brian Spett of Go Houselights, who does live shows all over the world.

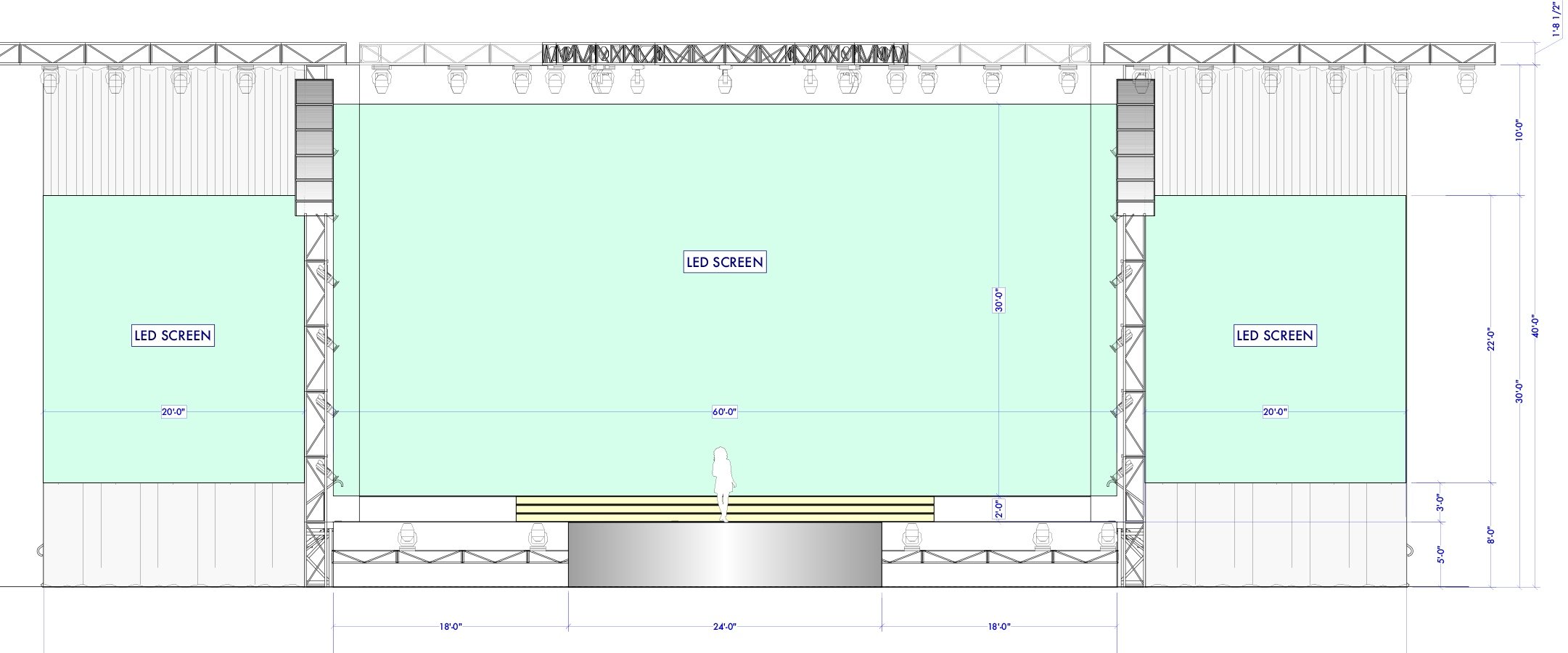

Discussions with Parker, Lester and costume designer Alexis Forte were crucial in order for us to build a concise color palette. Together we watched Renaissance: A Film by Beyoncé

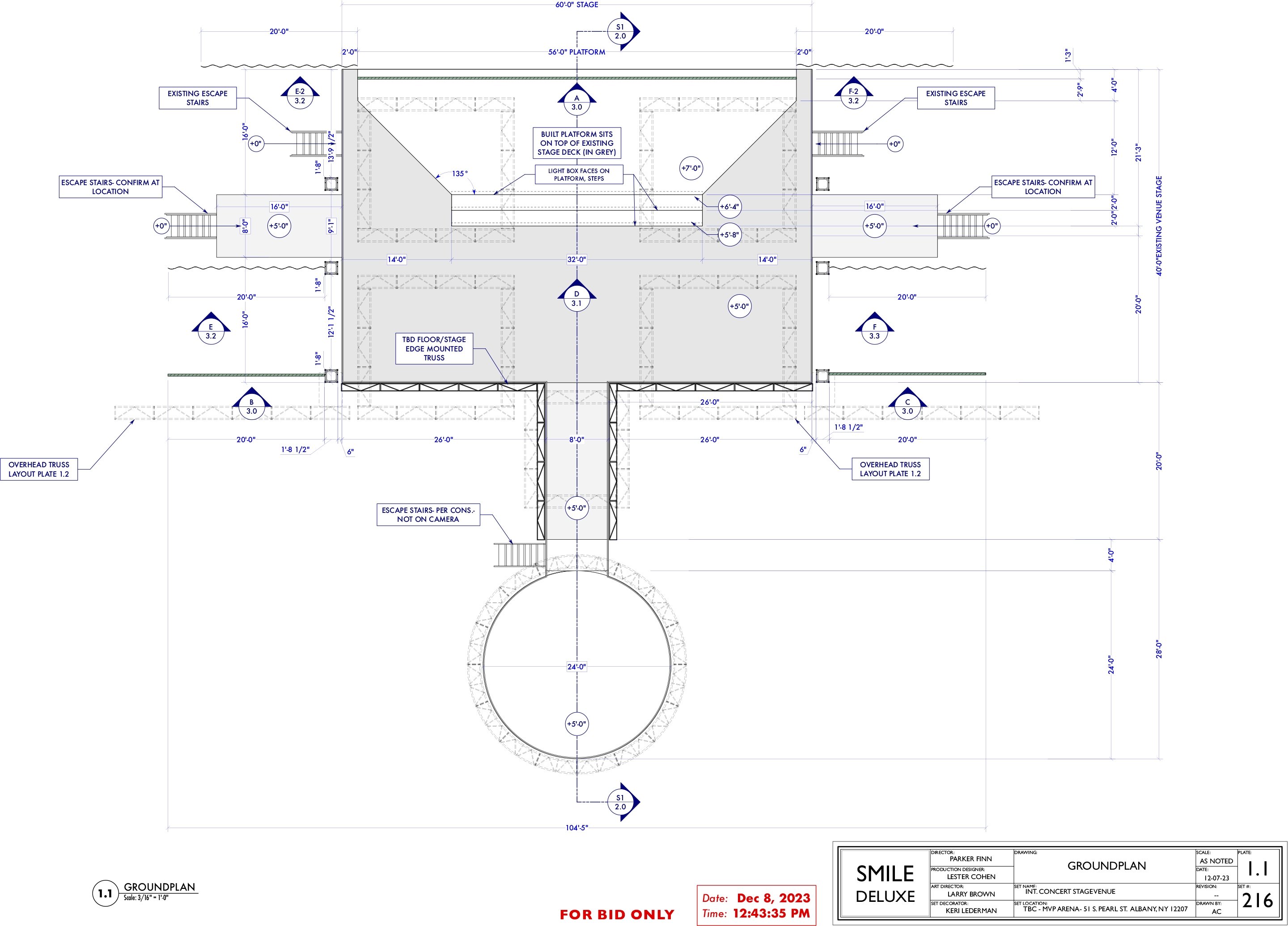

for inspiration. We chose mostly red with silver and blue elements, which also applied to the lighting and an animation consisting of various elements we shot that were displayed on LED walls behind Skye and her dancers. We had a central LED wall 56' wide and two side walls 20' wide each.

Brian programmed the video, and he and his team also helped orchestrate the build and the rigging. We had the arena for only six days, including four intense shoot days, but they made it happen. Brian and I had lighting plans going back and forth. We’d say, “Maybe we need some movers here or a spot there … maybe the LED will play there at this moment.”

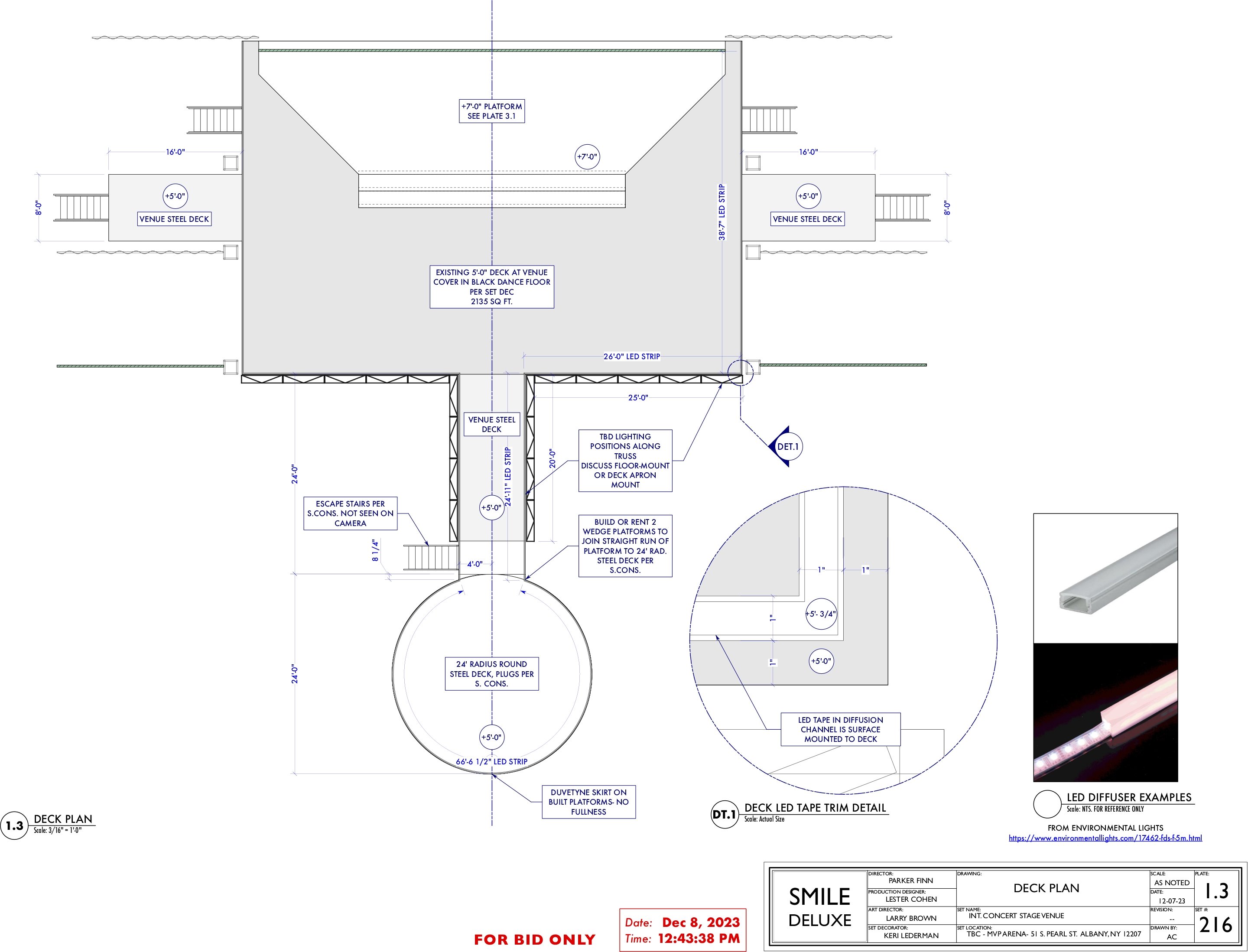

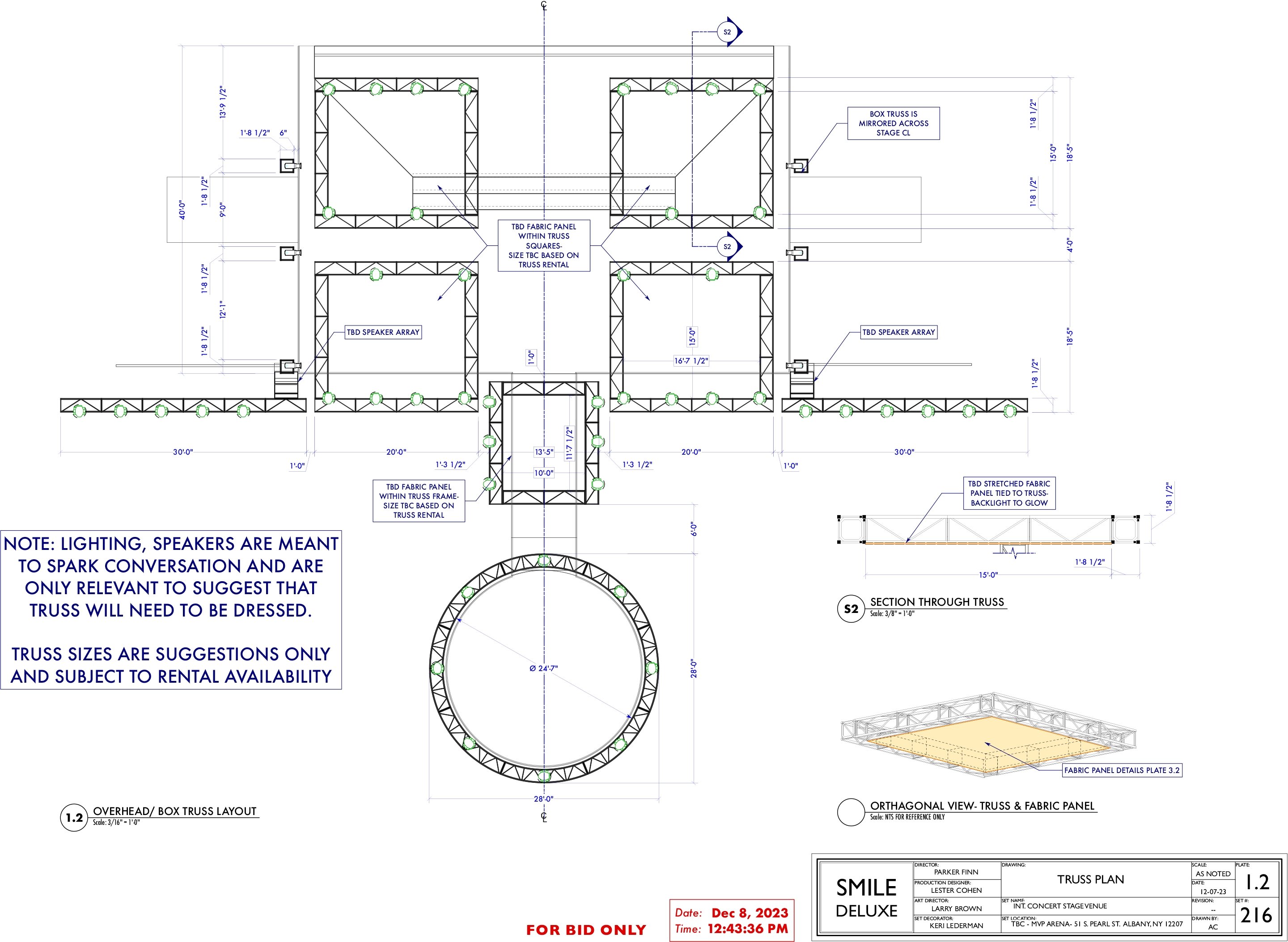

Above the stage, we had four box trusses each holding eight to 12 Acme Solar Flares, which can provide beam, spot and wash. Another truss at the back held four of these lights, as well as a Robe BMFL FollowSpot. The stage featured a catwalk to a smaller circular stage, over which we hung a box truss and a circular truss with Solar Flares. Robe Spiider LEDs positioned on either side of the stage provided a wash over the audience and dancers. We also got a bright beam from Elation Proteus Excalibur lights from the top rear.

We supplemented the stage lighting with film lights worked out by gaffer Joel Minnich, Brian and me. For example, when the camera was close to Skye onstage, the follow spotlights often caused camera shadows, so we’d bring in floor lights to get around that. Those consisted primarily of ETC Source Fours, Vortex8 LEDs and some HMIs. We used the Evoke 900C in a dance-rehearsal scene when the house lights dim up after an incident.

Shots in the performance incorporated a puppet element we had to shoot at Umbra Sound Stages in Newburgh, New York. I wanted interactive light on our subjects, which we then had to marry with the arena shots. Interactive light in the arena was no problem, but to then cut to material shot in the much smaller studio space with our puppet and lead on bluescreen, while keeping the lighting consistent, was a major challenge. I worked very closely with Robert on that, and I couldn’t have pulled off this sequence without his expertise or Brian’s. One of the most important things about being a cinematographer is surrounding yourself with people who know more than you, and then asking them for help.

As told to Mark Dillon.

Tech Specs

2.00:1

Cameras | Arri Rental Alexa 65, Arriflex 435

Lenses | Arri Rental Prime DNA, Heroes; Fujifilm/Fujinon Premista; Arriflex/Zeiss Super Speed MKII

Film Stock | Kodak Vision3 500T 5219

You’ll find Sarroff’s personal website here.

Below is a series of additional concert lighting diagrams supplied by the filmmaker.