Suspiria: Season of the Witch

Cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom helps juxtapose a scheming coven with the strife of postwar Berlin for Luca Guadagnino’s reimagining of a horror classic.

Photos by Alessio Bolzoni, Sandro Kopp, Mikael Olsson and Willy Vanderperre, courtesy of Amazon Studios.

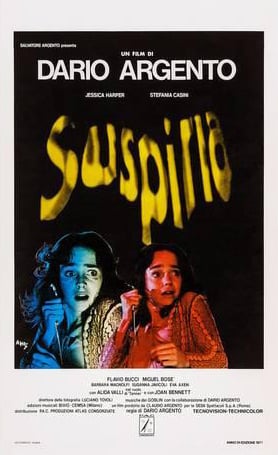

Early in Luca Guadagnino’s reimagining of Dario Argento’s 1977 giallo landmark, Suspiria, a panic-stricken young woman, dance student Patricia Hingle (Chloë Grace Moretz), bursts into the gloomy West Berlin flat of her psychiatrist, Dr. Josef Klemperer (Tilda Swinton, unrecognizable in prosthetic makeup by Mark Coulier), desperate and struggling to communicate the details of an experience at her school — something to do with witches.

In this sequence, the filmmaking is as frantic as the young woman. Cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom follows Patricia with a dolly-mounted camera as her eyes dart around the room, and editor Walter Fasano quick-cuts between jittery POVs of doors, windows, book spines, the extreme close-up of Klemperer’s note-taking in his diary — and an old framed photo of a young dark-haired woman (Suspiria ’77’s Jessica Harper, as Klemperer’s long-lost wife, Anke).

It’s a stark contrast to the wide-angled, Technicolor, blood-saturated sequence mirrored from Argento’s original (photographed by Luciano Tovoli, ASC, AIC; AC Feb ’10; complete story here), in which Patricia (Eva Axén) takes refuge at the home of a friend, and the two are subsequently killed by a knife-wielding attacker.

The premise of Guadagnino and co-writer David Kajganich’s new script closely resembles that of Argento and Daria Nicolodi’s: American dancer Susie Bannion (Dakota Johnson) travels to Germany to study under Madame Blanc (Swinton, sans prosthetics) at the prestigious and exclusive Helena Markos Dance Company, only to discover that this tanztheater fronts for a coven of murderous witches (played by a murderer’s row of European cinema grand dames), who are seeking a vessel into which they can channel the spirit of the decrepit and dying Markos (Swinton, again with prosthetics), who claims to be one of the three ancient witch “Mothers.”

“This is my standing point: I always shoot movies on film. Film cameras talk to me more than digital cameras.”

“When you dance the dance of another, you make yourself in the image of its creator,” Blanc tells her students. The filmmakers behind Suspiria ’18 all agree, however, that Argento’s film is a masterpiece, “so if we couldn’t make it more interesting, we should do something different,” says Mukdeeprom, a Thai cinematographer who collaborated with Guadagnino previously on Call Me by Your Name (AC, March ’18). It was during the production of that film that the director and cinematographer first began discussing a remake of Suspiria, but for Guadagnino, the plan had been in motion for much longer.

“My first encounter with Dario’s work was in 1981, when I was 10 and saw the poster for Suspiria hanging in a cinema,” Guadagnino reminisces. “I finally saw the film when I was 13, and I’ve been nurturing a passion for it ever since.”

The year in which Argento’s film was released served as a touchstone for Guadagnino’s Suspiria. It’s also the year of the infamous German Autumn: a series of events surrounding the kidnapping and murder of influential business executive Hanns Martin Schleyer by the Red Army Faction militant organization, and the hijacking of a Lufthansa airplane by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. The group demanded $15,000,000 in exchange for the hostages, as well as the release of 10 imprisoned RAF members and two Palestinians — which inspired the 1978 anthology film Germany in Autumn, directed by German New Wave legends Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Alexander Kluge, Edgar Reitz and Volker Schlöndorff, among others.

Guadagnino wanted his Suspiria to be a spiritual successor to the cinema of this era, which, he says, “reflected on the concept of contemporaneity and conflict with the generations of the past, the fathers and mothers who deny themselves the possibility to acknowledge what they did under National Socialism.”

“That era of the late Seventies is very [confusing, regarding all aspects of] Germany: politically, socially, and the light — everything mixed together,” says Mukdeeprom, who worked with Berlin-based gaffer Florin Niculae for the German segment of production. The infamous Berlin Wall may have fallen, but even today the cultural divide is still evident in the way the city is lit at night. Sodium-vapor lamps illuminate the East with a yellower color, while in the West, newer fluorescent, mercury-arc and gas lamps produce a whiter light.

Suspicion and subterfuge permeate every aspect of Suspiria, with its Cold War setting, the cruel milieu of a city divided, and fear of imminent, real-world terror around every corner. The filmmakers heightened and harnessed this oppressive atmosphere with a color palette that suggested myriad shades of brown, green and blue.

Principal photography commenced in October 2016. Mukdeeprom wanted Berlin to look “very somber, very sad” — an arguably easy ask for the German capital in the cold season. Production designer Inbal Weinberg notes, “We shot in Italy from October to December, and then in Berlin in February and March 2017.” As for the architecture, she recalls, “I don’t think I’ve ever seen that many shades of gray.”

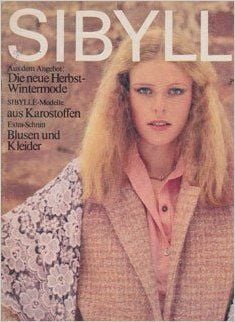

Costume designer Giulia Piersanti reports that she emphasized “muddy, muted army greens, rusty browns, camels and beiges — subtle colors that blended in with Sayombhu’s dark, sophisticated photography. These were true to the aesthetic of the German Democratic Republic, which was, in reality, a bit darker and bleaker than the propaganda pictures in [the magazine] Sibylle, whose colors were much brighter and emphasized. I also tried to use red as a recurring color to alert of the dangers to come.”

Sibylle, Piersanti says, was “an impressive fashion and culture magazine from the GDR,” from which she drew heavy inspiration. “It’s filled with incredibly dreamy, high-quality fashion shoots from around Berlin, and what was really amazing about it was that there were no real brands — it was supposed to be all from the ‘people’s own factories.’ It even had patterns to make your own clothes, so you could copy the fashion shoots. They were very hard to find, but I managed to find most of the issues from ’75 to ’79 on German eBay.” She further describes the publication as “Eastern Bloc Vogue.”

Regarding her collaboration with Guadagnino and Mukdeeprom, Piersanti notes that the three “had worked together on Call Me by Your Name — and I worked with Luca on A Bigger Splash — so we know each other’s processes very well, and how our work together can look as a whole. We have group readings and discussions where we all share personal notes, and Luca discusses his intentions. We also run early test shots with the actors in full costume, hair and makeup to see if all of our colors and textures interact correctly with the photography and the backgrounds.”

Mukdeeprom shot Suspiria entirely on Kodak Vision3 500T 5219 color-negative film — including day exteriors — without correction filters, and pushed it one stop to 1,000 ISO when needed. Cameras, lenses, grip and electrical equipment were rented from D-Vision Movie People in Rome, which provided an Arriflex 535A and two Arricam LTs, all configured for 3-perf Super 35 operation, and one 4-perf Super 35 Arriflex 435ES for visual-effects shots. Augustus Color in Rome developed the negative and delivered dailies. Colorist Alessandro Pelliccia performed both dailies and final color correction with Blackmagic Design DaVinci Resolve.

“This is my standing point: I always shoot movies on film,” says Mukdeeprom. “Film cameras talk to me more than digital cameras.”

Most of Suspiria takes place in and around the West Berlin neighborhood of Kreuzberg, an area close to the wall. “We didn’t actually shoot [in Kreuzberg], because it had gentrified beyond recognition since the fall of the wall, so we had to re-create that look in other parts of the city,” Weinberg says.

“If the director says the mood is dark, I will make it dark.”

The filmmakers spent two weeks on location — on the street; on bridges; under the U-Bahn tracks; at the Paris Bar, where the witchy mistresses of the tanztheater gather to carouse; at a space in Charlottenburg made to look like a cafe in Tiergarten. An abandoned GDR office building in Mitte was employed as de facto stages for the municipal police station, where Klemperer implores a pair of clueless polizei to investigate Patricia’s mysterious disappearance. This space was also used for the interior of Tränenpalast, or “the Palace of Tears” — the civilian crossing between East and West — while its exterior was shot at the actual site. Klemperer’s family dacha was filmed in the Berlin exurbs, and the Ohio Mennonite farm where Bannion grew up was captured at a rural location an hour outside the city.

The Helena Markos Dance Company was entirely and meticulously created in an abandoned hotel located in a mountain range near Varese in Northern Italy. All of the dance-company interiors were filmed there — lobby, dance studios, offices, kitchen, the dancers’ dormitories, and the secret ‘Mutterhaus’ with its cabinet of occult objects, its dark catacombs, and its ritual chamber.

Weinberg describes the hotel as “beautiful, with a really great flow,” but it was in need of major repairs. There was no electricity, no running water, and parts of the ceiling had caved in. “The other thing was that it was built in the late 1800s, so the architectural style was a little too Art Nouveau,” she remarks. (See additional interview, below.)

The production set about renovating the entire space, and in the process replaced many of its more decorative elements, augmenting the existing ornamental façades and columns with more modernist surfaces and details. Scenic artists painted faux surfaces of marble and granite, and the film’s construction crew patched walls, refinished the dance floor, and laid every tile in the building’s lobby.

“The environment will give us the mood and the feeling. So rather than try to create a look for the film, I wanted to create the world of the film, and approach it as if we just brought the camera there to photograph it.”

“We made absolutely every inch of space count,” Weinberg says. Klemperer’s flat was also filmed there, as was the exterior of the tanztheater, with its sidewalk, neighboring buildings, and section of the wall. For the street, Weinberg had concrete poured and embossed with cobblestones, and had streetlights imported all the way from Germany. “We went pretty far in trying to get things right,” she attests.

Mukdeeprom believed that the company’s dancers should be deeply influenced by their surroundings. “The environment will give us the mood and the feeling,” he explains. “So rather than try to create a look for the film, I wanted to create the world of the film, and approach it as if we just brought the camera there to photograph it.”

The way in which Mukdeeprom approached this world was primarily influenced by Guadagnino’s direction and Weinberg’s production design, as well as the movement of the actors. “I like to create a stage for Luca and the actors, so they have the freedom to move anywhere,” the cinematographer says. “Luca watches the frame, and if he chooses to go in for a close-up, it will be driven by the character.” Mukdeeprom adds that he generally lit “the whole set at once, like a stage,” and only on occasions when there was limited space would he light one angle at a time.

Having been asked by the director to do something visually different from Call Me by Your Name, Mukdeeprom notes that on their prior collaboration, “I used only one lens — a 35mm. For this one, I had every lens from 18mm to 100mm.”

In addition to the project’s Cooke Speed Panchro S2 and S3 prime package, the production also carried Cooke’s Varotal 18-100mm (T3) zoom and Angenieux’s Optimo 24-290mm (T2.8) zoom, as well as vintage Arri/Zeiss Super Speed (T1.3) glass. Suspiria was framed for the 1.85:1 aspect ratio.

When it came to moving the camera, Mukdeeprom, who was also the A-camera operator, strove to limit his options to what the cinematographers of the German New Wave would have used in 1977 — which meant no big cranes and no Steadicam. Germany key grip Radu Marinescu and Italy key grip Massimo Spina worked primarily with a J.L. Fisher Model 11 Dolly, a “pied de poule” (aka spider dolly), a MovieTech Magnum Dolly column and a Panther Foxy Pro Jib.

This is not to say that creative thinking was discouraged, however. In the scene where another disillusioned dance student, Olga (Elena Fokina), tries to flee the tanztheater but is confronted on the stairs, Guadagnino wanted the camera to track with Fokina as she descended the long, curved staircase. To accomplish this, Spina devised a system of pulleys that connected a 3-axis remote flight head and an Arricam LT to the track-mounted Fisher dolly on the seventh floor of the lobby. Spina referenced a monitor mounted to the dolly to follow Fokina’s action, and lowered the camera while operator Alessandro Barisano executed the pan with a remote Flight Head V system.

A-camera 1st AC Massimiliano Kuveiller employed Tiffen ND filters to maintain a T2.2-T3 — and sometimes T1.3 — exposure at night, and T4-T5.6 during the day. Tiffen diopters were used for capturing detailed shots without the use of a macro lens.

The spirited camerawork that opens Suspiria and continues throughout its 152-minute runtime is another departure from the filmmakers’ previous collaborations — with the addition of dramatic snap-zooms and split-focus shots, the latter with the aid of classic split diopters, to their repertoire.

Second-unit cinematography and B-camera operation was assigned to Carolina Costa. She performed her cinematography duties alongside 2nd-unit director Ferdinando Cito Filomarino (director of 2015’s Antonia, produced by Guadagnino and photographed by Mukdeeprom). Using the first unit’s shot list and Italy gaffer Francesco Galli’s lighting plots as a reference, Costa occasionally picked up shots for Mukdeeprom on the production’s busiest days, when first unit was rushed to move on after getting a master and reverse. “Those were rare circumstances, though,” Costa says. “The second unit was actually formed to shoot Suspiria’s dream sequences.”

In the film, as Bannion settles into her new life as lead in the tanztheater’s latest production, her sleep is disturbed by dreams of her childhood home, the protracted death of her mother, and colorful, haunting visions sent by Madame Blanc to entice her young protégé into submission. “We used some color here, only because the sequences are unconnected with reality,” Mukdeeprom says. Galli fashioned a custom lamp — two 1,000-watt tungsten bulbs mounted to an aluminum base at the end of a boom, wrapped with 1⁄4 Grid Cloth diffusion and two layers of Lee Lime Green, and controlled by two Magic Gadgets flicker boxes — to augment the ghostly green apparitions that envelop Bannion in her dream-state.

Otherwise, Mukdeeprom was restrained in his use of color and subtle in his application of light. “We wanted to have minimal impact in all the stage scenes, and give maximum freedom to move camera and actors,” Galli says.

In the dancers’ dormitory, 12' x 12' greenscreens were rigged on condors outside each window, above which were placed — on another condor — two side-by-side Arri 4K Fresnels fitted with Chimera’s Daylite Plus M and DOPChoice’s SnapGrid. Also employed were 12K Chimera units fitted with Lighttools Soft Egg Crate. The combined rigging provided a soft, blue-gray atmosphere on the set.

According to Mukdeeprom, the dorm was one of the film’s darker sets, where even with practical lamps, incident exposure hovered from 2 to 21⁄2 stops under reflectance. “If the director says the mood is dark, I will make it dark,” he notes. “It will be properly exposed; I’m just working at the lower part of the curve.”

“I check everything with my light meter. Even if I’m at the deepest, darkest point of the curve, it’s there, and because I shot on film, I can do a digital intermediate and have the best of both worlds.”

Lighting the dance-theater interior scenes from overhead seemed like a practical approach, and simultaneously kept the lamps out of the way of the actors and filmmakers. In the spacious practice room, every unit — three massive chandeliers, and 20 Arri SkyPanel S60-Cs fitted with 1⁄2 Grid Cloth and the units’ proprietary Diffusion Panels — was routed through a manual Strand dimming system operated by Matteo Attolini.

Swinton, as Madame Blanc, channels the spirits of such modern dance legends as Pina Bausch, Rudolf von Laban, Mary Wigman and Martha Graham — driving the dancers relentlessly forward to the opening night of Volk, an avant-garde expression of suffering in postwar Germany (choreographed for Suspiria by Belgo-French artist Damien Jalet) that also doubles as a spell-casting ritual dance. The dancers, with their near-nude bodies draped with knotted, bright-red rope — meant to evoke “dripping blood,” Piersanti explains — twist and writhe between the points of a pentagram taped out on the dance floor.

Galli and Mukdeeprom turned to theatrical lighting designer Giordano Baratta to produce the light for the Volk performance, while they focused on the main aspects of production. Baratta conceived a bare-bones layout — consisting of just a few 1970s-era plano-convex spotlights — that was run through a Jands T2 lighting console to form hard, diagonal slashes of intersecting light. “A ‘Dante’s Inferno’ between the demonic and the lightness of the bodies,” Baratta calls it.

From its beginning to the gruesome showstopper, it took an entire week to film the performance, the cinematographer reports. Apart from adding a third camera, operated by Filomarino, to his and Costa’s, Mukdeeprom notes that he approached the scene in much the same way he had the rest of the film: “We just let it happen.”

The Helena Markos tanztheater’s subsequent climactic performance takes place far from the public eye, and is staged in honor of the monstrous “Mother” Markos, who has chosen Bannion as her next host. The company’s entranced students enter the immense Mutterhaus chamber, and begin a theatrical ritual dance.

The “hair dresses” worn by the dancers in this scene, Piersanti says, “were made from real human-hair extensions. [The dresses were] studied one by one, by sketch first, then draped onto a cage-like grosgrain ribbon base to keep them as free as possible for the movement of the ritual dance performance. Each night after we filmed, they were all cleaned of ‘blood’ and re-brushed into place.”

“We are at the very heart of the [witches’] world — a secret place, and I wanted to create a different kind of stage for them,” Mukdeeprom notes. Here, Weinberg’s production design took its cues from surrealist paintings, contemporary art installations, and performance art. The cinematographer wanted the ability to capture the set all the way up to the ceiling, so he, Galli and crew lit the ritual stage from across the room with 750-watt ETC Source Fours, using a combination of 10-, 19-, 26-, 36-, and 50-degree lenses, all through Hampshire Frost, as well as 1,000-watt PAR 64 lamps with spot and flood bulbs.

The ritual is interrupted when Bannion achieves a supernatural transformation, which plunges the Mutterhaus into darkness, save only for a soft, red light just barely bright enough to make out the grisly, incendiary fate of the coven’s unbelievers in a sequence filmed at variable frame rates — 6, 12, 25, 50 and 100 fps — with the intention of mixing them in post.

“I check everything with my light meter,” Mukdeeprom says. “Even if I’m at the deepest, darkest point of the curve, it’s there, and because I shot on film, I can do a digital intermediate and have the best of both worlds.” The cinematographer further notes that the aforementioned red light was in fact achieved “in color correction by adding red to certain regions, rather than to the whole [room] as [an actual] red light would do.”

In addition to processing and dailies for Suspiria, Augustus Color also provided film scanning, final color correction, and mastering services. The film’s title and credit sequences, digitally created by graphic designer Dan Perri, were filmed out to 35mm, printed, and re-scanned at 4K resolution. Mukdeeprom’s original camera negative was digitized as 10-bit Log DPX files at 2K for the approximately 1,000 visual-effects shots, and 4K for the non-visual effects shots.

“[As] Luca said to us during day one of color grading, digital intervention had to be invisible, with an analog flavor,” Pelliccia explains. “Sayombhu wanted deep blacks without losing information in the details, and Luca wanted a realistic atmosphere with gray skies; dark, dense tones; low saturation; and no high contrast. With extensive use of Resolve’s RGB Mixer and Layer Nodes, every effort was made to find the right key, scene by scene, to enhance the ‘color feelings,’ which allowed us to better isolate subjects — such as shadows, faces, set decoration — from the background.

“Even though he has a masterful knowledge of cinema from the technical point of view, Sayombhu’s priorities are more humanistic than technical,” Guadagnino extols. “More importantly, he has a masterful knowledge of cinema from the storytelling perspective — the part of the film that has to do with human beings and their emotions.”

“I was just very honest with the script,” Mukdeeprom notes. He suggests that the success of any collaborative art form — be it film, music, dance or witchcraft — ultimately depends on the successful interaction of a team. As he says, “You have to let everyone show off.”

Aesthetics and Identity

Production designer Inbal Weinberg offers thoughts on her collaborative work in the film.

It’s 1977 and a coven of witches is on the verge of reconstituting their nefarious leader at a Berlin dance company in the retelling of Dario Argento’s horror classic Suspiria. Directed this time around by Luca Guadagnino and shot by Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, the production called upon the services of production designer Inbal Weinberg, who took some time with AC to discuss the creation of the film’s eerie, period-specific environments.

American Cinematographer: From a design standpoint, what was your relationship to the original Suspiria and the work of production designer Giuseppe Bassan before you started on the remake?

Inbal Weinberg: I always felt like I started this project from scratch. The original is so over-the-top, visually, and is so specifically of the oeuvre of Dario Argento — a world with its own look. Our storyline is similar, but the horror elements are conceived differently and have maybe even different symbolism in terms of the visuals.

Different in what way?

What’s really interesting about the script, to me, are the historical and political layers that you can link with the ideas of horror and violence. It’s a psychological exploration into the darkness of humanity, and there are definitely connections to Germany’s past — specifically Berlin in the 1970s, which was a divided city and had an interesting social mise-en-scène rooted in the wall. We were going for this kind of bleak, modernist feel that plays into the concept of German identity presented in the film. I know Berlin well and I speak German, but up until Suspiria, I didn’t think a lot about the wall and what it meant. [The 1970s] was an era of decline for Berlin. It’s such a complex place. Its people lived with a rip down the middle of their lives. But there’s a banality to it — an acceptance.

What can you tell us about your research into the real-world history and architecture?

Luca and I had similar references for the architecture. Some of it was contemporary to the Seventies, so I went deep into historical research of the time. Then we delved back into the beginning of 20th-century modernism, specifically as it relates to Austrian and German architects and designers. I’m talking about the forefathers of modernism, before Le Corbusier, who were trying to move beyond Art Nouveau. Adolf Loos was a large influence on us, as was Josef Hoffmann. We liked their use of marble and granite, and different stones and geometric lines. Loos wrote an essay called Ornament and Crime in 1908 just after the period where Art Nouveau had reached its peak and became so decorative that it was drawing a counter-movement calling for the abolition of all ornament. We thought that was more in the spirit of our film, that beneath the banality of everyday life lies this dark, otherworldly power.

In Suspiria, that dark, otherworldly power possesses a distinctively ornamental aesthetic, however — all curves, fine detail and coarse textures.

In terms of the underworld elements, we looked at surrealist paintings — [as well as naturalist] architecture, such as [the work of] Antoni Gaudí — but a lot of our references came from contemporary performance art and installation art by women artists. These ended up being our strongest references.

How would you describe your collaboration with the film’s cinematographer, Sayombhu Mukdeeprom?

It was an interesting collaboration because Sayombhu is Thai and he’s a Buddhist, so he has a different way of perceiving things. Even on location scouting, he would stand back and let Luca and me talk, and just receive the information. Obviously, I consulted with him about anything that had to do with lighting, practicals or window dressing and so on, but there’s also his inclination to photograph things as naturally as possible, with as little ‘influence’ as possible. I’d seen it in his other films, and I thought it would work beautifully here, because the world we were building was already a visual one.

Sayombhu described his approach in terms of using the spaces as a stage. Was this an element of your production-design technique as well?

I would say the most stage-like sequence we had was the performance of Volk. For that, we reconfigured the rehearsal-room set as a stage, and even worked with a lighting designer from the theater and opera — but in terms of the design, I didn’t really feel like there was a stage. At a certain point, it did start to feel like we were living there. It was a tough production experience, and we had moved our offices into this abandoned hotel where we worked for months. I suppose I’ve lived in all of my sets. Actually, in my house in New York right now, next to my house keys are the keys to Klemperer’s dacha, because in a way, these places will always be a part of my life. — Iain Marcks