Personal Battles: Southpaw

Director Antoine Fuqua and Mauro Fiore, ASC aim for maximum authenticity in the ring.

This article was originally published in AC Aug 2015.

Unit photography by Scott Garfield, SMPSP

“I’ve been boxing since I was a kid,” says director Antoine Fuqua. “I love the sport of boxing, and I love the science of boxing. When I go to fights, there is an energy in those arenas that you feel. The air is thick with a sense of violence. Once the bell rings, the fight starts and it’s just two men, going at it pound for pound.”

Fuqua’s passion permeates Southpaw, which stars Jake Gyllenhaal as boxer Billy Hope; Rachel McAdams as his wife, Maureen; and Forest Whitaker as Billy’s mentor and trainer. The film — which follows Hope through his fight to the top, the tragic events that tear his life apart, and his struggle for redemption — was shot by Academy Award-winning cinematographer Mauro Fiore, ASC, whose collaborations with Fuqua include Training Day, Tears of the Sun and the upcoming Western The Magnificent Seven.

“Southpaw is a project that Antoine has been passionate about for a long time,” says Fiore. “We talked about this film four years ago, and finally the Weinsteins decided to produce with Jake in the starring role.”

As Gyllenhaal was training — triple sessions daily alongside Fuqua — the director started talking with Fiore about how to “get into the head of Billy Hope and conceptually deal with his breakdown,” the cinematographer says. The idea they came up with was two-fold. First was the look they hoped to achieve from each of the four fight scenes in the movie: “Reality,” explains Fuqua. “As close to reality as you could possibly get in a film.”

Second was to tell Hope’s story through each fight. “We didn’t do a lot of specific storyboarding,” Fiore says. “We tried to let the action lead the concept. Antoine wanted the first fight — which takes place at Madison Square Garden — to be the introduction of the fighter and his character. It’s very observational, with an objective viewpoint.” The fights that follow become increasingly subjective. In the second fight, notes Fiore, “we are slowly getting into the ring with him, and into his head.” And it’s a brutal match — or as Fuqua puts it, “self-punishment. A sense of guilt and an attempt at suicide.”

By the time the film reaches the final fight, “we’ve mounted cameras onto the fighters, so you become part of Billy’s mind and expression,” Fiore says. “You experience the fight the same way he does.”

Fuqua’s ambitious plan was to shoot all four fights in the first two weeks of production. “We had a lot of doubt at first,” admits Fiore. “Jake and the other fighters had to be prepared to go all the rounds of each fight without stopping, and we were rolling the whole time. It was exhausting for them, but it ended up being incredible, due to Jake’s preparedness and Antoine’s intensity in getting the action in a continuous run.”

Each fight was highly choreographed, says Fiore, thus calling for substantial rehearsal time. “We had monitors for every camera, the same way you would in TV coverage, and we ran through what everyone would be doing,” says the cinematographer. “We’d specifically communicate after we filmed each fight; we’d play back and observe, and talk about what we could do to improve.”

The filmmakers turned to HBO World Championship Boxing as their model, particularly for the first fight. To ensure authenticity, the production brought on two seasoned HBO Boxing camera operators, Todd Palladino and Rick Cypher. Palladino, a 13-year veteran of HBO Boxing as a ringside handheld-camera operator, explains, “We did multiple takes of the fight sequences, including different camera angles, as well as rolling straight through. [During those extended takes] we averaged two to four rounds of boxing, with each round being three minutes long without a cut, covering it like a live televised fight. [Shooting ringside] is so intimate; it really brings the viewer into the action.”

Palladino adds that on occasion, he has nearly been knocked out of the ring. “You try to anticipate the direction the boxer will go, but I’ve had some near misses where the glove has hit the camera. Once in awhile, I’ll get splattered by sweat or blood, which can take you out of the game a little bit.” No strangers to scripted drama, Palladino and Cypher worked previously on The Fighter (AC, Jan. '11) and Grudge Match. “We’ve become Hollywood’s go-to guys for fighting movies, I guess,” Palladino lightheartedly observes.

Fuqua and Fiore attended an HBO match at Madison Square Garde to both observe and shoot background plates. “The visit to Madison Square Garden for a fight was when it all came to life,” Fiore recalls. “It’s a huge, spectacular event. Production designer Derek Hill and I had already done a lot of research into the HBO world of fighting, and at the fight, we were able to walk around, talk to every technician and even get lighting diagrams.”

The plate shoot focused on a center block of the audience, which would be used to re-create a 360-degree view via visual effects. “We were collecting massive audience plates,” says Fiore. “The scale is incredible when you have so many people.”

These large audience plates were a crucial acquisition, as the location that would stand in for Madison Square Garden was a modest space at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. “That's what was available, and we tried to create the ring as accurately as possible,” says Fiore. “We could put in our lighting rigs and stay there for the period of time we needed to shoot. Even if the scale wasn’t accurate, the center of the ring was.”

Fiore gave the maps and diagrams of Madison Square Garden to lighting-console programmer and operator Kevin Hogan, who explains, “They asked me to figure out the rig, but there were hundreds of fixtures and perimeter trusses, and it wasn’t possible for us to do. So there were a lot of discussions about how much to shoot practically and how much would be expanded in visual effects.” With a mandate to create as much footage in-camera as possible, Fiore also conferred with visual-effects supervisor Sean Devereaux on the specifics of virtually expanding the arena.

To re-create an HBO-style experience, the production employed six Arri Alexa XTs supplied by Arri Rental. Radiant Images provided the lens package, as well as Vision Research Phantom, Silicon Imaging SI-2K Mini and Red Epic Dragon cameras, which were used for specialized shots. HBO is specific about camera placement, a blueprint Fiore followed as closely as possible. “One camera is in the middle of the audience, and you get left and right of the ring,” he says. “[They are] very specific as to height; you had to see above the second rope, meaning the fighters would be clear of all the ropes.” According to 1st AC Larry Nielsen, an Angenieux HR 25-250mm (T3.5) zoom was used for these shots.

Another camera was above the ring near the location’s ceiling, 40'-50' up, and captured the image for the Jumbotron. “In Madison Square Garden, the operator has a huge pedestal camera with zoom controls in a steel deck above the audience,” says Fiore. Nielsen reports that the high-angle camera used in the film was fitted with an Angenieux Optimo 24-290mm (T2.8) zoom.

Palladino and Cypher were positioned ringside on the left and right, standing on 2'x2' wooden camera platforms at the same level as the fighters. “Those cameras concentrate on the corners, but also follow the fight and zoom in according to the action,” says Fiore. When it came to choosing the zoom lens for this specialized work, Fiore conferred with the two battle-tested authorities themselves. “They were very familiar with the Alexa and briefed us on what lenses would be best for us,” says Fiore. “They were the experts and they consulted with us on every detail to make it accurate.” Palladino reports that their Alexas were outfitted with Fujinon Cabrio 19-90mm (T2.9) lenses with manual zoom controls.

“We [pulled] all our own focus on all three movies we’ve done,” Palladino says, though he is quick to point out that he has “major respect for focus pullers — they amaze me. Rick and I are used to running our own focus for boxing, and once you’re accustomed to it, it becomes second nature. There are times when we miss our focus, but we’re getting pretty good at it.”

“Todd and Rick cover everything, close and wide, in the fight,” says Fiore. “And as the fighters go into their corners, each [operator] takes a fighter. It doesn’t matter if you see the other camera because that adds to the accuracy; [that is what] you see in a live event.”

Palladino notes that he and Cypher wear black clothing and “try to blend in. We’ve been working together for so long, it’s like a marriage. We know what we have to do just by looking at each other.” For maximum authenticity, a camera assistant maintained the camera cable, which at an actual HBO boxing event would run all the way back to the broadcast truck.

An Alexa was mounted on a Giraffe crane with a Talon remote head positioned 12' off the ground in one of the corners, which, as Palladino notes, “was used in conjunction with the cameras Cypher and I were operating for alternate-angle knockout shots.” Both Alexa and Phantom cameras were used for slow-motion knockout sequences.

The production also used Angenieux Optimo 15-40mm (T2.6), 28-76mm (T2.6) and 45-120mm (T2.8) zooms on the Alexa cameras, as well as Cooke S4 primes.

The Alexas recorded ArriRaw to Codex hard drives. “We’d continually roll and fill up the whole card on one take,” says Nielsen. “We had a loader on the show who would go to the camera truck and download onto a Codex Vault and from there transfer over to a shuttle drive and backup drive for redundancy.” Dailies were generated on-location with Avid.

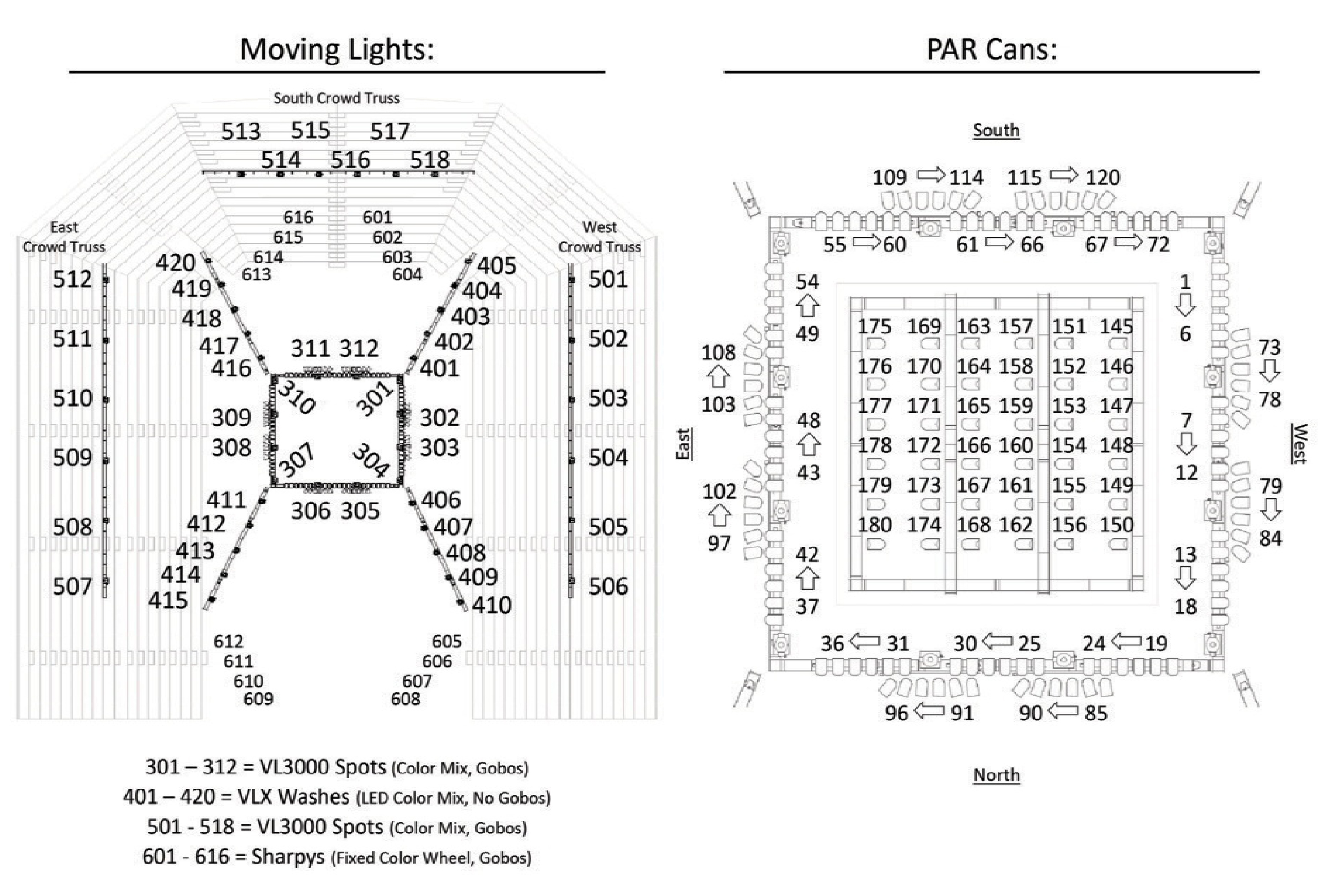

Moving lights were key to creating an authentic look for the fights. Hogan was brought on early to program the fixtures on his ChamSys MagicQ MQ100 lighting console; he used Cast Software’s Wysiwyg to design the lighting rig and previsualize the lighting cues. “I was able to do my entire setup a few weeks before shooting,” says Hogan. “This was very helpful to see what would work and what wouldn’t. I’d turn on a light in [Wysiwyg], and Mauro or [gaffer] Jon Morrison would suggest where to move it. We were able to make all those decisions on the computer model without having to make changes on-site. Thanks to that, we were able to fly the rig once and didn’t have to move things once it got in the air.” Hogan reports that by the time all the fights were programmed, he had a total of more than 800 cues.

Fiore describes the underlying technique in lighting the ring as intermixing “movie lighting and concert lighting.” The fight-rig fixtures included 156 Par cans on the truss immediately surrounding the ring, 20 Vari-Lite VLX LED Washes and 28 VL3000 Spots for moving lights, and 16 Clay Paky Sharpys on the ground to create searchlight-beam effects in the air. “The Sharpys are featured fairly heavily,” says Hogan. “They’re in the background of every shot. In addition to the moving lights, we used a staggering amount of cable: 12,650 feet — or 2.4 miles — of six-circuit multicable.”

To light the actors in the ring, Fiore placed a large soft box above the center. “We wanted to sculpt the light around our boxers,” he says. “We put a lot of our efforts toward the center of the ring.”

Morrison notes that the soft box provided a lot of flexibility. “We hid it in the grid above the ring, and we had complete control over whether we wanted it dark or light on a specific side or wanted to focus light into the ring,” he says. “We could raise or lower the lights within the soft box for more or less intensity. By making a decision to throw a lighting-control device over the soft grid hanging above the ring, we allowed ourselves greater flexibility — we could roll with the punches. We used all the lights in the truss to backlight or front-light the actors, and we used those moving lights to get nice rims on their heads or bounce off them.”

The university location stood in for three different fighting venues — the first, second and fourth matches — and Fiore determined that all four fights would each have a different color palette. “The first fight was Madison Square Garden blue, with lots of blue moving lights — a cool, observational palette,” he says. “The second fight [which takes place in Atlantic City] begins to use greens. The third fight, in a church, is a warm, red setting. And the last fight, Billy’s redemption, takes place at Caesars Palace and goes with even warmer tones — golds and oranges, the colors you’d see at Caesars.”

The second fight — a particularly brutal and bloody one — shows Billy’s downfall. “It’s a very tragic event for him,” says Fiore. “We started to experiment with different lenses for specific moments. A couple of times we used [a Lensbaby] for Billy’s disoriented point of view.” A-camera operator Kirk Gardner also got into the ring with a Red Dragon fitted with a Cooke MiniS4 prime and mounted on Freefly Systems’ Movi M10, a gyrostabilized handheld rig. “[The Movi rig is] much smaller than the Steadicam,” says Fiore. “You don’t wear it; you hold onto it, and the fact that you can put the camera almost on the ground and lift it up to somebody’s face makes it a pretty interesting rig that can create some really long shots.”

By the end of the second fight, Hope has destroyed his boxing career by knocking out the official. “It’s a beautiful Shakespearean moment,” says Fiore. “We’re still objective, watching him fall apart. There are some POV shots, but it was about an active, chaotic camera that reflects his [state of] mind. It’s still basically HBO style, but it was important for us to get into the characters’ minds a little bit.”

The third fight, which takes place as a fundraising event, serves as Hope’s comeback. “This is the beginning of [Billy’s regaining of] his confidence and sense of self-worth,” says Fuqua. “The fight is a reminder of what boxing is about — the sweet science.”

“It’s re-creating the time when boxing was a community event,” Fiore adds. The sequence was shot inside a former church, which has since been converted into a banquet hall. “The lights are very basic,” the cinematographer explains. “There are four 1,000-watt Skypans, one in each corner, lighting up the boxers in the center. You have the red glow of the ring — not the blue of the [previous] fights — and stained-glass windows in the background. The idea was to make it a spiritual moment, capturing the intimacy of the environment.”

The fourth and final fight is not only Hope’s triumph, but also recalls the Sugar Ray Leonard match in which both boxers are exhausted by the 12th round. “It’s the definition of a champion,” says Fuqua. “It takes more than boxing skills to get you off that stool when you are bloody, hurt — broken lungs burning. And yet you still get back up to give and get more punishment to win the fight.”

By this point in the film, the audience is alongside Billy in the ring. His point of view was captured with the extremely compact SI-2K Mini — recording to a Convergent Design Gemini 4:4:4 — which Fiore mounted on Gyllenhaal. “He did two rounds with the camera mounted,” the cinematographer says. “There’s a backpack for the batteries [which Gyllenhaal wore], and a hard drive that cinches onto the body. We filmed this section separately [so the rig was not in the other cameras’ frames]. At other times, Kirk was in the ring with the Movi rig. All the technology we had came together in this fight. We used [HBO-style] coverage, ringside cameras, subjective POVs and the Phantom for the final knockout.”

With multiple cameras shooting non-stop for all four fights, an unusually large amount of footage was generated. “The editor, John Refoua, kept saying, ‘Great, great!’” recalls Fiore. “‘The more I have to play with, the better.’”

The DI for Southpaw took place at Technicolor’s Seward and Tribeca West facilities, where colorist Skip Kimball worked with Blackmagic Design’s DaVinci Resolve. “Skip is a very experienced colorist who comes from a photochemical background,” says Fiore. “We’ve collaborated on several projects in the past, including Avatar and Real Steel.”

Fuqua points to his close collaboration with Fiore as being key to realizing his storytelling goals. “We cast the movements and lenses and look of the movie as if we were casting another lead actor in the film,” the director says. “Mauro and I have collaborated five times, as we are [now] filming The Magnificent Seven. Every time, we discuss story and work very closely together on every aspect of the look of the film.”

TECH SPECS

2.39:1

Arri Alexa XT, Vision Research Phantom Flex, Red Epic Dragon, Silicon Imaging SI-2K Mini Angenieux Optimo, HR; Fujinon Cabrio; Cooke S4, MiniS4; Lensbaby

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.