Space Cases: Guardians of the Galaxy

Ben Davis, BSC blasts off for this Marvel Studios space adventure.

Unit photography by Jay Maidment, SMPSP

Images courtesy of Marvel Studios and Walt Disney Pictures

Despite having first appeared on pulp in 1969, Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy comic books were unfamiliar to cinematographer Ben Davis, BSC, before he signed on to shoot the big-screen incarnation. He was quickly brought up to speed with the concept, though, when director James Gunn took him for a stroll through the art department early in pre-production. “The design work was flabbergasting,” Davis says, still with a sense of awe. “It blew me away. Concept work that is only limited by imagination can set a very high bar, and my job was to bring it to life. That challenge, for me, was the most enjoyable aspect.”

Unlike Marvel’s usual fare, which hangs Earth in the balance as superheroes square off against equally powered villains, Guardians is at its core a space adventure, set in the distant cosmos and populated by humans, humanoids, and all manner of strange aliens. In the film, crafty space pilot Peter Quill (Chris Pratt) — whose chosen moniker of “Star-Lord” does not precede him as far as he thinks — daringly swipes a powerful orb only to find himself the subject of an all-out bounty hunt led by the evil Ronan the Accuser (Lee Pace). With the fate of the galaxy threatened by Ronan’s plans, the intergalactic police force known as the Nova Corps pressures Quill into an alliance with his rivals: the green-skinned Gamora (Zoë Saldana); a tree-being of limited vocabulary called Groot (voiced by Vin Diesel); a weapon-wielding raccoon named Rocket (voiced by Bradley Cooper); and a tattooed and scarred mass of muscle known as Drax the Destroyer (Dave Bautista). And thus, the titular team is born.

Guardians marks the first collaboration between Gunn and Davis, as well as their first foray into what Marvel has dubbed its “cinematic universe.” (At press time, Davis was hard at work on his second Marvel movie, Avengers: Age of Ultron, with director Joss Whedon.) Davis began his career at the Samuelson Group’s camera house in the U.K. and rose through the ranks to photograph such features as Layer Cake, Stardust, Kick-Ass, The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, Wrath of the Titans, and Seven Psychopaths (AC Nov. ’12).

For the U.K.-based Guardians shoot, Davis opted to work with Arri Alexa XT cameras rented from Panavision London. He framed for a 2.40:1 release and recorded in the ArriRaw format off of the 4:3 2.8K sensor to the cameras’ Codex recorders. “I’m traditionally a photochemical fan,” he says, “but going with the digital format was the right way for this movie. Technically, all the digital cameras are good. I just felt the Alexa [provided] the right look for this particular project.”

Before launching into space, the film opens with an earthbound sequence that features a young Quill. For these scenes, Davis employed JDC Cooke Xtal (Crystal) Express anamorphic prime lenses, which began their lives in the 1930s and ’40s as Cooke S2 and S3 spherical lenses but were rehoused and modified with anamorphic elements in the 1980s by Joe Dunton Cameras. “I picked the lenses that didn’t go off the shelf much,” the cinematographer notes, adding that the Xtal Express lenses “had more anamorphic artifacts and aberrations, which I felt added something. We had a 50mm that said T2.8 on it, but it was more like a T4 and had a lot of edge distortion. I liked the look of it.”

For the rest of the picture, Davis switched to spherical Panavision Primos. Davis notes, “Marvel likes to have a bit of room for visual effects [to reposition the frame in post]. When we shoot anamorphic, there is not a lot of frame height to play with, whereas if we extract 2.40:1 from a 4:3 image, there is a lot of room to maneuver. Shooting spherical was the right decision.”

The filmmakers favored wider lenses to take in the characters and surroundings. “James wanted Guardians to be an intimate film, so we stayed close to the actors on, say, a 24mm as opposed to being 10 feet away on a 50mm,” Davis says. “We worked a lot in the range of 17.5mm to 27mm in order to show off the sets, which were very large. The film was mostly shot in the T2.8 to T4 range, and if there were parts of a set we wanted to see more of, I would float more light there.”

Two Alexas were employed the majority of the time, with a third and fourth added on occasion. “I don’t mind working with two cameras at 90 degrees from each other,” Davis says. “If it’s three, I’ll work a wide and a tight down one axis and the third camera at 90 degrees. Over the years I’ve become much more adept at lighting for multiple cameras.”

hunters chase after Quill. The exterior set was surrounded by bluescreen so visual effects could extend the alien terrain in postproduction.

Davis emphasizes that Guardians was largely filmed on highly detailed, practically built sets as opposed to expanses of greenscreen and bluescreen — although both frequently served as trim for set extensions in post. To realize the extraterrestrial environments, Davis worked closely with production designer Charles Wood. The cinematographer enthuses, “That was the exciting thing for me, getting these crazy concepts of mad worlds and figuring out how we would [realize them in front of the camera]. Fortunately, we had the time in prep to work out how.”

The cinematographer was particularly struck by the number of practical lighting sources that were evidenced in the concept drawings. To carry this idea into the sets, the crew wired upwards of 15,000 DMX dimmer channels to control the built-in fixtures. “I made a creative decision to not use any traditional lighting fixtures — your typical Fresnels or HMIs — on this film,” the cinematographer explains, wryly adding, “In prep, that sounded like a great idea. For a space movie, any fixture that is in shot has to feel like it’s futuristic. At the same time, I didn’t want to go with what you so often see in space movies: bits of white Perspex with lights behind them. We spent a lot of time trying to source fixtures that looked like they could be part of a world set in the future, and a lot of those were predominantly LED or tube fixtures. We visit worlds that are so disparate that I felt having a unified lighting strategy would bring them together with a continuity of look so that the film felt as one piece.”

reveals the addition of CGI characters Rocket and Groot.

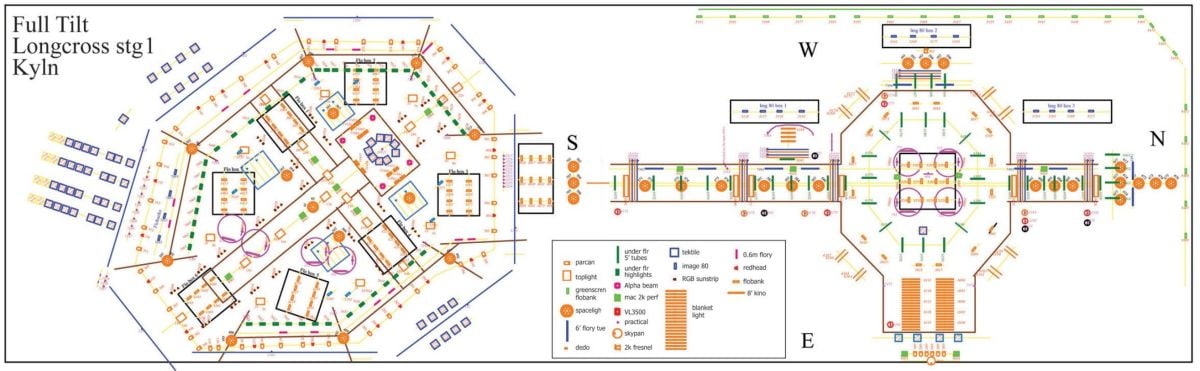

One of these worlds houses the Kyln, an intergalactic prison where Quill and his future teammates are held after being captured by the Nova Corps. The set was built in the 300'-long stage at Longcross Film Studios, a former Ministry of Defense construction and testing facility for tanks, located in Surrey. (The production also worked out of Shepperton Studios.) The Kyln set comprised a multi-level system of tunnels lined with prison cells that led to the main yard anchored in the center by a four-story watchtower. “I was very adamant that [all of the lights] come back to a central dimmer desk because we had different scenarios to play within that space,” Davis says. “We had a day look and a nighttime lockdown setting [with the practicals at a low level or off completely], and we wanted to see that transition. When the Guardians break out of prison, there is also a red emergency-light/alarm setting.”

For a base ambiance over the yard, Davis and his longtime gaffer, David Smith, sought to create the feel of light emanating from space. To achieve this, they devised a series of overhead softboxes filled with Panalux FloBank tungsten fluorescents gelled with ½ CTB and aimed through Full Grid textiles that had been dyed with Lee Filters 728 Steel Green. (Davis and Smith decided that Steel Green would be the de facto color for all space-originating light in the movie.) The ambient light was about a stop and a half below the rest of the set lighting.

Additionally, the art department constructed massive, 660-pound ring lights that could appear on camera as set pieces. Smith explains, “Each circle had nine Par 64 bulbs in it, and we clustered them together on electric motors below the soft boxes so we could take them up and down. When we were on a wide shot, we could drop them in to break the frame. They worked for a mid-ground, on-camera set piece as well as providing great light. We ran those lights at 25 percent, so they were really quite warm in terms of color temperature.”

Hoverbots, each sporting a searchlight, serve as prison guards in the Kyln, and although the bots themselves were CG visual effects, the searchlight gags were created in-camera with Philips Vari-Lites and 189-watt Clay Paky Sharpy moving fixtures. The lights were suspended around the set, and some were mounted on tracks for additional movement. “Panalux also made us a joystick so we could put a Sharpy on the end of a camera crane and manually point the light rather than [pre-program its movement],” says Smith. “We moved the crane and the light like you would a remote head.”

Various other tungsten-balanced lights were also rigged throughout the set. “The art department would make a shape, and we’d put a fixture inside it, whether it be a fluorescent, LED or Par can bulb,” says Smith. “We had about 8,000 DMX channels in there by the time we finished. Some of the fixtures we used were RGB LED so we could create different colors in areas, and some of them had 75 channels per fixture.”

Davis adds, “If [the actors] were being hit by colored light, we’d let it play. Color is really important in Guardians. You see a lot of space movies that are quite monochromatic, but we looked at a lot of images from the Hubble Telescope and were struck by how much color was in them. We’d sometimes use a contrasting color to pull the talent away from the background. I generally tried to bring the flesh tones to something more normal with neutral key light.”

However, what qualified as a “normal” flesh tone was relative, considering the various hues of the film’s aliens, including the green-skinned Gamora. “I cannot tell you how many tests we did to get a shade of green makeup that we felt worked,” Davis recalls. “If we shot [Saldana] in a wide shot, she’d generally be half to two-thirds of a stop down from every other character in the scene — the green just absorbed the light. I would try to make sure she was closest to the key light in a scene or that it at least favored her. A lot of times I would have a Source Four Leko on her if I could put one in. In post, there was quite a bit of work to window her and pull her out.

“Unfortunately,” the cinematographer continues, “the green we came up with that was most photogenic was not far removed from chroma-key green. If we had time, we’d drop a bluescreen in behind her. But for visual effects — considering they were creating a walking, talking tree and a raccoon — keying Zoë off a greenscreen was probably the least of their problems!

the greenscreen set

where the

Guardians come

face-to-face with

Ronan the Accuser

and his loyal

lieutenant, the

assassin Nebula

(Karen Gillan).

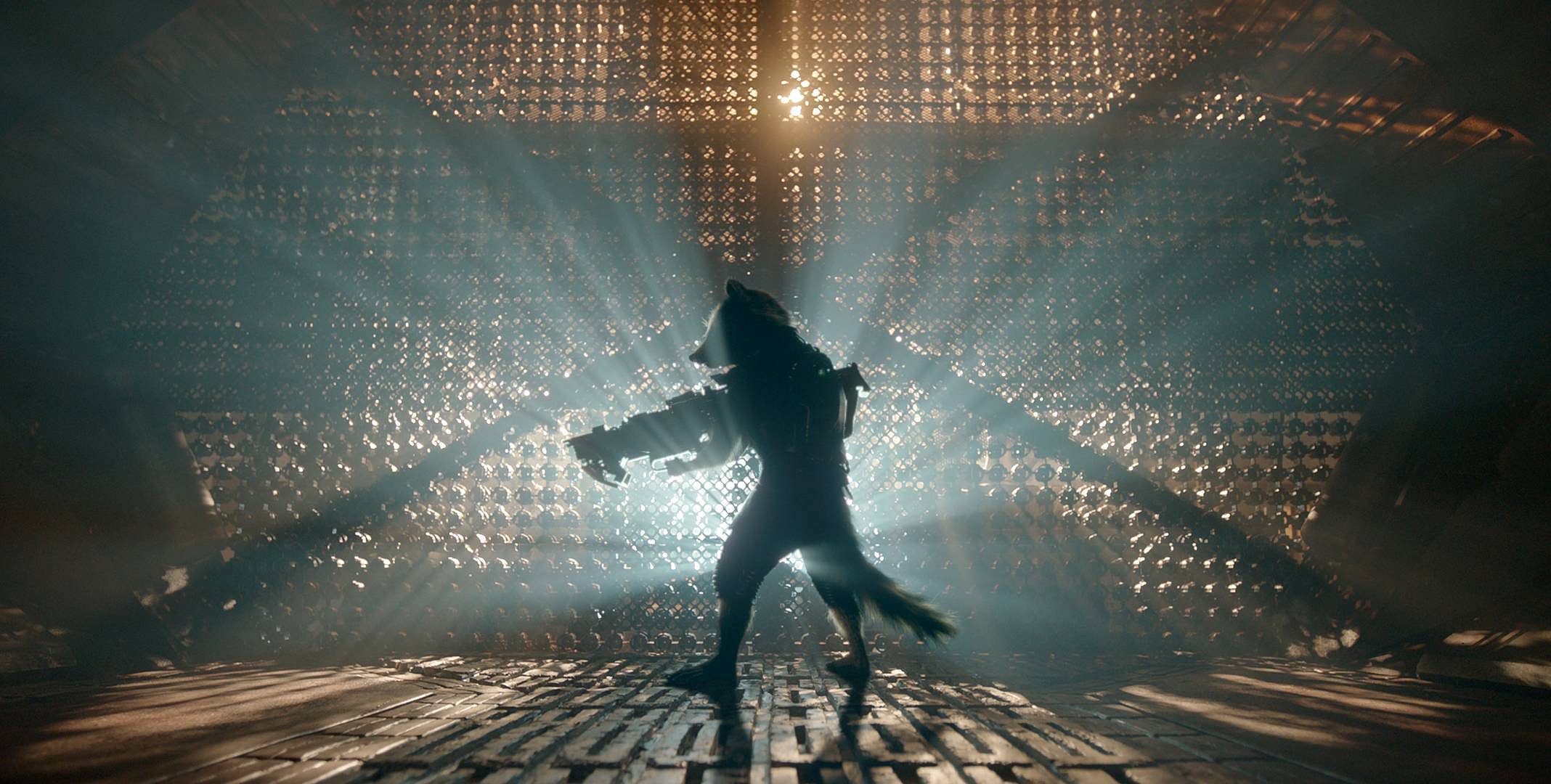

“Even when we thought we weren’t shooting a visual-effects shot on one of our four-wall sets, we were reminded that we had two lead characters who are visual effects,” says Davis. “So almost every shot was a visual-effects shot. We had Sean Gunn [James’ brother] down on his knees in a blue suit playing Rocket. Groot didn’t have many lines, so we had a stick with a tennis ball on the end [to provide] an eyeline. We’d run a pass with those two, and then we’d do a pass without.”

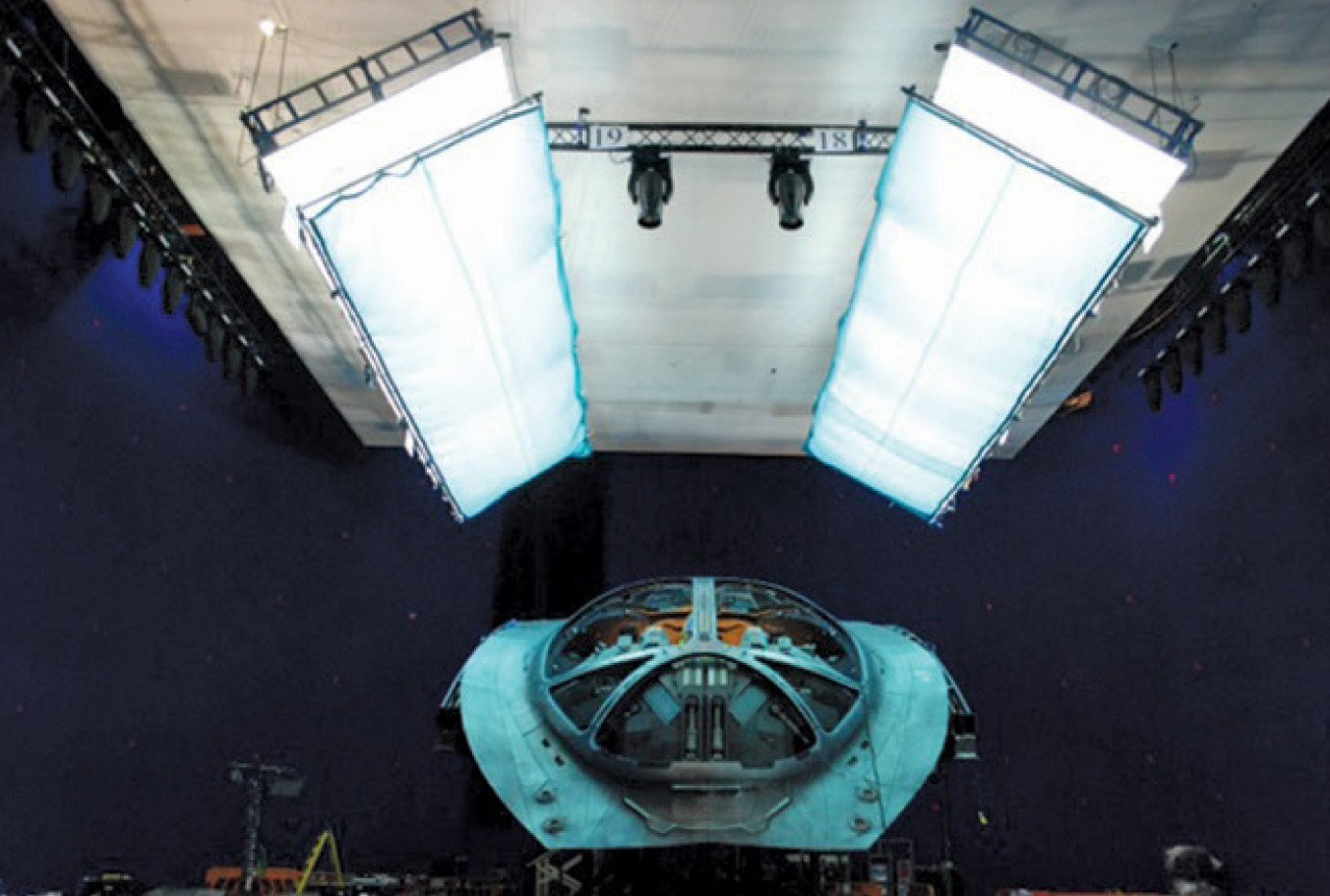

The Guardians travel in Quill’s spaceship, the Milano, the interior of which was built on stage as a two-level set with a flight deck positioned above the lower living quarters, enabling the actors to move freely from one deck to another within a scene. The cockpit could be removed from the rest of the set and placed on a gimbal for battle sequences. Davis notes that the cockpit “was a compact set with a lot of characters in it. The idea was that it should light itself with practical lighting.”

Smith adds, “Everything [in the cockpit] was [primarily] fluorescent or LED, with barely any tungsten lamps — maybe the occasional Source Four or Dedolight to pick something out. Otherwise, we’d put in 2- or 3-foot T5 tubes and strips of LED ribbon run back to dimmers.”

For shots looking out from within the cockpit, its large, bowl-shaped glass canopy was left in place so that reflections of the Guardians could be captured. However, when the camera looked into the cockpit from outside, the canopy was removed in order to avoid unwanted reflections of equipment. (The greenscreen surrounding the cockpit was illuminated with Panalux FloBank fluorescents.)

Above the cockpit, for scenes when the Milano is in space, Smith and Davis employed a softbox of fluorescent Panalux HighLites through Full Grid dyed with 728 Steel Green. They also devised a number of interactive lighting elements to simulate the ship’s transition into the Earth-like, daylight atmosphere of Xandar, the utopian home of the Nova Corps.

“We built a horseshoe-shaped rig 21 feet high that went from one side [of the cockpit] to the other,” Smith explains. The cockpit, he adds, “was about 14 feet off the stage floor,” and the horseshoe rig incorporated a series of side-by-side 2'x2' Panalux TekTile 60 daylight LED panels. “We could chase those lights backward and forwards to make it look like the cockpit was spinning,” the gaffer continues. “We also had TekTiles going along the top of the ship, so we were able to chase them as though the ship was going in a forward motion. Above that we had a roof of silked daylight fluorescent HighLites that we also chased to give a feeling of movement. On either side of the cockpit, we had 12 Martin Mac Viper Profile [moving fixtures], which we could swipe through to give us a little more movement. And above the ship we had Vari-Lites rigged to sweep across. My desk operator [Onkar Narang] got worked!”

Additionally, a 20K was positioned on a crane arm to serve as a hard “sun” source, and Panalux HiLo Softsource fixtures were mounted to the end of a Grip Factory Munich GF-16 Crane, capable of up to a 50' reach, to move around the cockpit as a key light. The newly developed LED light has a progressively adjustable color temperature range between 3,000K and 6,000K. “We were really the first show to put the Panalux HiLo to the test,” Smith says. “They were originally designed to compete with the space light, but we ended up having stirrups made for them and using them on stands as a conventional light.”

Davis adds that the HiLo Softsource is “dimmable without any flicker. I liked [the fixture] so much that I put several of them together and put them through a large frame for a big soft source for key lights for other setups.”

The Guardians also fly the Milano to Knowhere, one of the more unusual settings found in any science-fiction movie. Knowhere isn’t a planet in the proverbial sense, but rather the skull of a long-dead god floating in space. The surface has sprouted a kind of frontier community of prospectors who mine the skull’s yellow cerebral fluid. Because it is in the shadow of a black hole, Knowhere exists in endless night.

A street on Longcross Studios’ back lot was dressed as the frontier outpost and dolloped with pools of yellow fluid. Davis initially planned to light the street with soft boxes hung from cranes, but the British summer brought high winds, so instead the cinematographer opted for two 70' sections of truss, each suspended 35' high by cranes, one at each end of the street. On each truss, 30 weatherproof housings were mounted perpendicular to the truss at 4' intervals; each housing was fitted with two daylight fluorescent tubes gelled with 728 Steel Green.

At street level, Davis says, “there were a lot of open storefronts, so I used a lot of practical lights. I wanted the street to light itself from practical fixtures — a lot of tubes on the walls and small tungsten fixtures.” The street ran along the side of a soundstage, atop which the crew installed a 200' walkway where they could position Nine-light Maxi-Brutes fitted with CP60 spot bulbs; dimmed to a low level of light — just enough to register — the globes were aimed straight down to pick out particular areas of the set.

The Boot of Exitar bar serves as Knowhere’s main hub of activity. “We built 2-by-2 TekTile LED panels into the entrance [of the bar],” says Smith. “The art department dressed them with grills to make a semicircle of light. Inside, there were a number of fluorescents and Par cans behind grills to make it bright and vibrant.”

Davis adds, “Charlie built these wonderful light casings into the set. They were made of metal so they could cope with the heat from the lights — we used Par 64 bulbs in them. We also used a Martin Mac Aura RGB LED. I generally don’t like RGB LEDs; I’m not particularly keen on the wavelength of the colors. I’d rather use a tungsten lamp and gel it, but I was limited with what I could place in the structure, and the LED fixtures didn’t generate much heat.”

Smoke and haze typically permeated the sets, providing a level of diffusion in the air — without the need for diffusion filters on the lenses — so that the colorful worlds were more believable and less cartoony. “The challenge with shooting multiple cameras in those situations is balancing the cameras, because the amount of smoke [varies] between the subject and each camera,” Davis explains. “In post you try to balance through contrast, to deepen the blacks on the cameras that are farther away and thus have more smoke between them and the subject.”

Davis viewed projected sync rushes from the edit rooms at Shepperton. He says he was careful not to get bogged down in on-set image tweaking. “For example,” he says, “I had one particular CDL that covered the whole of the Kyln sequence. Because I come from a film background, I prefer to have a print-emulation LUT. With digital cinematography, it is very easy to get lured into spending all your time in a little black tent.”

The final digital grade was conducted in 2K at Technicolor in Los Angeles. Davis had his hands full shooting Age of Ultron, but he would stop at Technicolor U.K. after wrapping for the day for a transatlantic session with colorist and ASC associate member Steven J. Scott. The cinematographer notes, “Though most of the color is in the photography and the design, we selected particular colors to push in the DI. What I didn’t want to do was take color collectively and saturate it, because I think that is a very naïve approach, a sledgehammer approach, to color. We took a particular color, keyed that color to separate it, and then we’d push that color up. That may have been done with two or three colors in each shot, so there was a lot of work done in the color timing.”

2.40:1

Digital Capture

Arri Alexa XT

Panavision Primo (spherical), JDC Cooke Xtal Express

For more from Ben Davis, check out his work on followup Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 in our Behind the Scenes with Guardians piece from June 2017.