Star Trek 50 Part III — Effecting Wrath of Khan

Industrial Light & Magic visual effects supervisor on creating memorable work for the 1982 Trek sequel.

The third entry in our 12-part retrospective series documenting 50 years of production and post on the Star Trek franchise.

Mama Eel and the Nebulae

During the last few years, I’ve flown spaceships down the Death Star trench in Star Wars, dodged asteroids and fought Imperial Walkers in The Empire Strikes Back. I also had baby dragons devour a princess and their mama battle an old sorcerer in Dragonslayer — not exactly your everyday routine. Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan was no exception.

Before any work could begin, we had to study every storyboard concerned with the optical effects. Attending our initial meetings were Nicholas Meyer, director; Bob Sallin, producer; Joe Jennings and Mike Minor, art directors; Rose Duignan, production manager; Steve Gawley, chief model maker; Jim Veilleux and myself. Once we understood the movie, its dynamics, character and the intent of the shorts, we started to organize departments and basically set the mood of Trek II through the ILM facility.

Once all the script revisions were complete, several wheels were set into motion. Steve Gawley and the model shop started building the U.S.S. Reliant. Editorial, headed by Art Repola, organized to handle the tons of film that would be passing through that department. Camera tested ships against blue screen, nebulas, explosions, etc. Optical started doing some test composites and all of us saw a lot of difficult work ahead of us with hardly any time to do it — a common complaint of special effects companies. Soon, we were right in the middle of it.

Ceti Alpha five is a planet of little or no resources. Hot, desolate and arid, it’s a planet where just staying alive is next to impossible. There is one species native to Ceti Alpha: the eels. This aspect of the film was contributed by Bob Sallin, and he gave me the task of designing and bringing to life these bizarre critters. Taking all the particulars into account — story significance, planet’s weather, terrain, etc. — I went about drawing different versions of the animals. I wanted an organic look to them. That is, a look that appeared naturalistic and believable — not something so alien and weird that an audience would have a hard time accepting it. I guess I succeeded. Several people I spoke with thought they were real garden variety bugs!

I sculpted the mama eel in Roma Clay. Sean Casey of the model shop made molds of it and cast it in Schram foam (a very flexible foam rubber). The casting was cleaned up, and fitted with a mechanism to move the jaws (in real life a modified tea strainer), and the tail was rigged with a metal rod to move it. The shell was of hard urethane cast separately from the eel, and applied later before painting. The paint was acrylic mixed with latex rubber, and sprayed with Armor-All to keep it from rotting.

There were many other eels made. Small ones for the scenes of Chekov (Walter Koenig) and Captain Terrell (Paul Winfield) screaming as the eels inch along their faces. This was a simple technique of monofilament tied to foam rubber eels, dipped in a clear, thick slime, pulled along their faces in an inch-worm fashion. It took many takes to get the right shot, and both Koenig and Winfield had to endure having some very gooey bugs messing up their faces. Lucky for me they had so much patience. They were great sports, and never tried to break my neck once!

Eels five inches long were made for the shots of the creatures slithering into the victim’s ear. A large ear was made to duplicate Chekov’s ear. The eel that exits the same ear later in the film was 6 ½ inches long and sculpted to be more developed. All had the basic mechanics of the mama eel.

Panavision equipment was used to shoot these sequences, using an anamorphic zoom lens. Mike Owens was assistant, Sel Eddy operated, and I directed. We shot on Fuji 250, to match to the live action that Gayne Rescher [ASC] (director of photography) shot. It worked great!

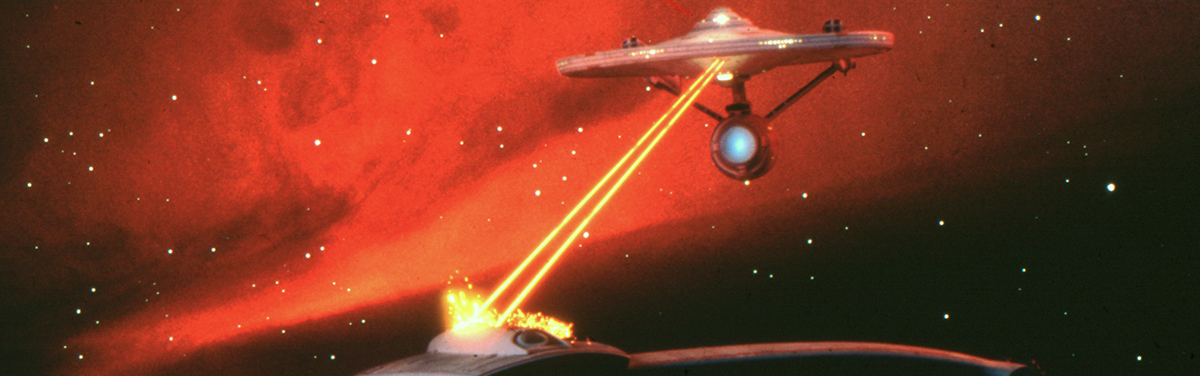

The first time the spaceships Reliant and Enterprise meet, the Reliant fires on the Enterprise, and a small skirmish between the ships follows. Since spaceships in space are not exactly new, we wanted something to set it apart from all previous space flights.

Both Enterprise and Reliant are majestic ships, something akin to grand whaling vessels at the turn of the century. Now, being a closet Trek fan from way back, I wanted to capture some of the boldness and spirit the show had in its visuals. One way was to continue the use of star fields — with an accentuated sense of depth to them — a technique crudely done on the TV series. We refined this effect by creating all the star fields for the show by computer. The Evans and Sutherland Company in Utah supplied all the start field effects — the sensation of depth is subtle and striking, adding a nice edge to the battle.

The model of the Enterprise already existed, built by Doug Trumbull’s effects crew on the first Trek movie. The Reliant, however, had to be built from scratch. Once a design was settled on, the model shop geared up and constructed it in record time. It’s a gorgeous model, perfectly constructed for shooting. It’s light (vacuum-formed sections over a very light aluminum interior frame), highly detailed, non-reflective (easy to shoot using the blue screen matting process), and could be easily mounted from all sides for any possible setup.

The camera crew, Don Dow, Eddy, Owens and myself, shot all the models with the same motion control system used on Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back.

We tried using an f-stop of 32 for maximum depth of field, and shot about one frame every 2 seconds. For the long scenes it might take 10 hours to shoot one element. Much of the lighting for the ships followed Trumbull’s lead, except we styled it with a bolder stroke. All our lights had a 212 yellow gel to make Bruce Nicholson’s job in the optical department easier. The slight yellow tint aided in eliminating blue spill problems from the blue screen, and gave Bruce better information on the negative to help him give us the best mattes this side of the Pecos.

There is battle damage sustained by both ships in this sequence. The Enterprise and the Reliant are hit by phasers, causing severe injuries. The hit on the Enterprise was achieved by animating (actually painting) the scars from the phaser on the body of the model, then using the same timings, we shot a glow pass on the model. A small light on the rheostat was moved across the ship at varying exposures. After all was done on stage, Sam Comstock and the animation department took our footage and enhanced it with explosions, sparks and the phaser. The damage on the Reliant was done by using miniature and high-speed photography. The late Bruce Hill shot all our slo-mo effects, and did, as usual, a great job.

The rear dome of Reliant, which was hit, was built of wax and breakaway glass, and filled with a network of wires and explosives by our in-house pyro genius Thaine Morris. We shot a lot of 16mm tests in the early stages, using the action-master camera. This helped immeasurably to narrow down the look we wanted, and how we would approach it technically. After the tests, we brought Bruce in and shot all our explosions (360 frames a second), in one very well organized day.

Rose Duignan did a fabulous job coordinating all the different factors of our part of the production. It’s one thing to try to just do the work, but organizing what model goes to what cameraman when, who flies to Los Angeles tomorrow, who returns tonight, etc. is a near impossible task. I think she must be cloned into ten different people, because one couldn’t possibly handle it.

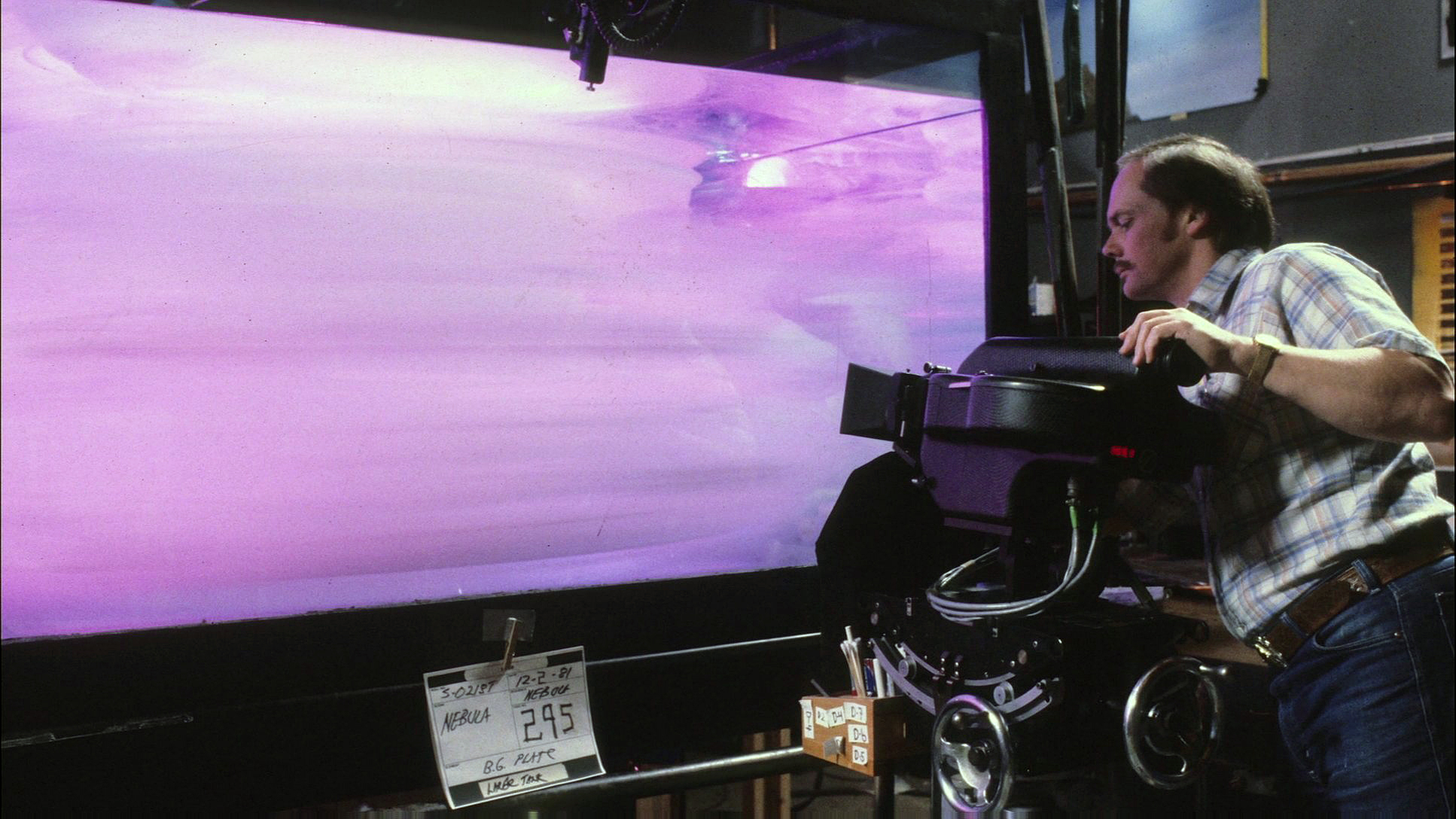

The sequence in the nebula is the most visual part of the film. Ships maneuvering, playing cat and mouse deep inside the colossal Mutara nebula — a battlefield of huge, swirling gases and explosive energy. Getting the “look” of this alien environment was very important, and much time went into experimenting with various approaches, materials, unusual compounds, any and everything to achieve what we wanted. Chemicals might work, or matte paintings, but still they weren’t quite it. Finally, Don Dow and crew came up with an answer. By using a solution of latex rubber mixed with ammonia, and injecting it into a mixture of salt water and fresh we created incredible abstract shapes that constantly were moving and changing.

The constant movement was what made it so interesting to look at, and so damn difficult to photograph. Since the latex was white, all the colors were done with gels on the lights. After the mix was placed in the tank, and currents to shape it created, it was a matter of standing back and letting the stuff do whatever it wanted. Certain shapes lent themselves to certain colors and combinations of colors. It was like playing Beat the Clock. Once the clouds formed, I’d determine what color scheme worked best, what went where; and while I was yelling directions, the crew raced to set lights just right, put just the right gel and scrims on them, then we’d set the shot up, quickly determine exposure and the amount of time per frame of film (5247) and, most important, cross our fingers. If we weren’t fast enough we’d miss it. Generally after several takes, the cloud tank would disperse too far to continue, and we’d have to empty and clean it, then refill it to try again.

It was difficult maintaining any sort of continuity with this abstract system, and we had to shoot a lot of film to give us enough material so I could give the nebula sequence a cohesive look from shot to shot. One nebula shot in October would have to cut with one shot in January: colors, shapes, the works. The occasional energy blast inside the nebula was accomplished by moving an inky around the tank, shining the light in different areas of the clouds, altering its intensity from frame to frame. Any additional light effects, such as the sensuous energy auroras, were done in the animation department. Sam Comstock reflected light into strips of mylar, then onto a rear projection screen, and shot them at very slow speeds.

The ship models were lit differently in this sequence. They all were lit to match the bizarre colors of their backgrounds — yellows, reds, orange, etc.: each scene a different color scheme. Lighting ratios were increased to heighten the drama of the nebula and more backlighting was used.

After all elements for a specific shot were complete, they’d go into our editorial department. Art Repola handled my sequences, and finessed all the timings of ships, explosions, nebulas, etc. He’d take all the separate pieces of film, sync them up for maximum effect, then send them to optical to be composited together.

The last problem to solve was filming “Spock’s coffin” on the tropical virgin Genesis Planet. Of course, virgin anything these days is hard to find, so we had to create it. Because of limited time, we went to nearby San Francisco and beautiful Golden Gate Park. We scouted out the park, and found a tropical, overgrown area, not too far from ILM, and planned the shoot for that spot.

Stu Barbee was operator, Owens assisting. Our grip department, headed up by Ted Moehnke and Pat Fitzsimmons, moved us in and handled the equipment and the tulip crane we used.

We shot on Fuji and used the Panaflex with assorted lenses. The crew shot from 3 a.m. to 7 p.m., moving around the park, making sure we got the shots. This was due to the fact that we were nearly out of time, especially for reshoots. Thaine Morris smoked the park up to add a primeval ambience. We had greensmen place extra ferns around to accentuate the lush surroundings of the park, a few HMI’s were used to help the sun, back reflectors were our fill and a fiberglass coffin our “star.”

After the location shoot, we added a scene of clouds taken from the stockpile we acquired for Dragonslayer and put in a matte painting by Frank Ordaz to start the sequence off.

We managed to complete all the effects within our budget, and on time – which was a task all its own. Each job is a new challenge, and it makes for an interesting, sometimes exciting way to make a living.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.