Star Trek 50 Part VII — Next Generation Production

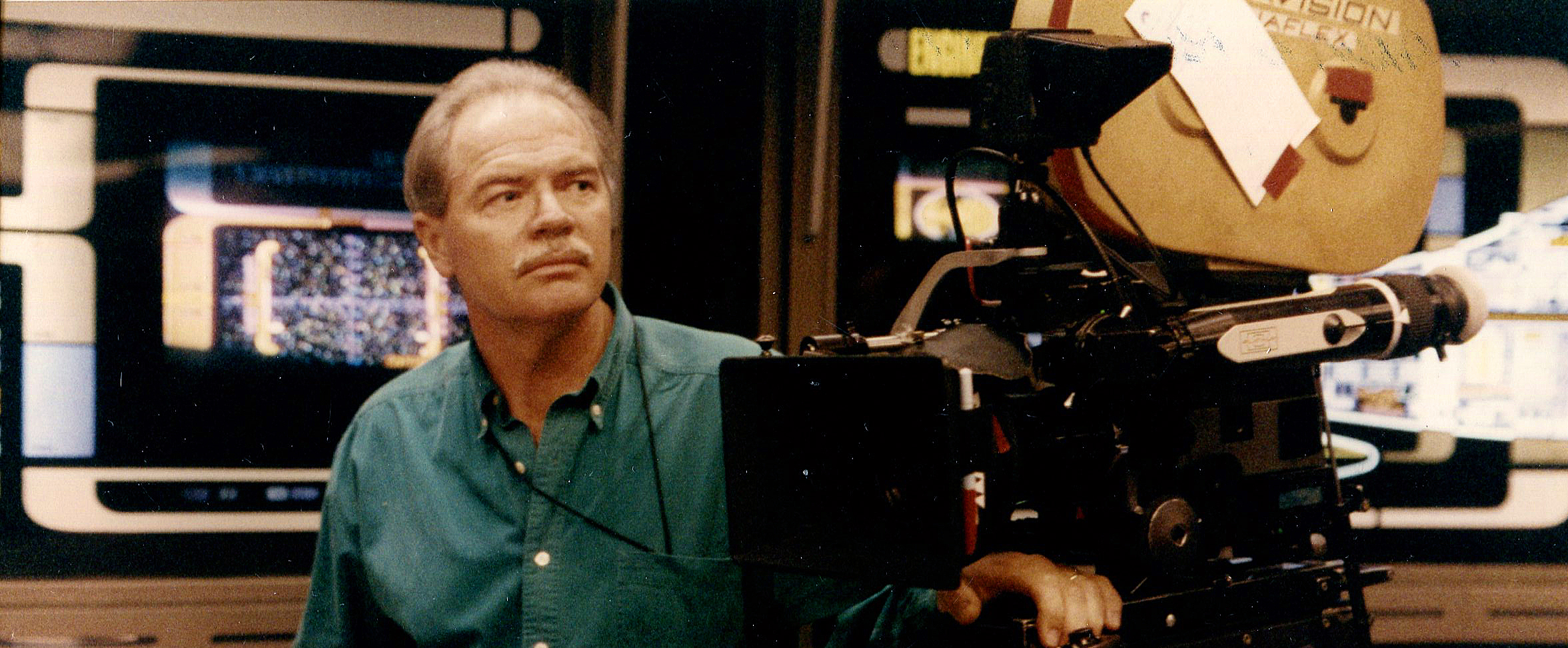

Marvin V. Rush, ASC and visual effects supervisor Robert Legato, ASC detail their approach to the Trek series reboot in this archival interview.

The seventh entry in our 12-part retrospective series documenting 50 years of production and post on the Star Trek franchise. Here, cinematographer Marvin V. Rush and visual effects supervisor Robert Legato detail their approach to the Trek series reboot in this archival interview. Both later became ASC members.

TV Sci-Fi Hits Warp Speed With The Next Generation

Throughout the annals of the United Federation of Planets, intergalactic intelligence reports have never indicated that Klingons are gourmands with a taste for 20th-century California cuisine.

In the lounge area of the U.S.S. Enterprise, however, Lieutenant Worf, the ship’s irascible Klingon officer, is offering a tantalizing tip to a fellow patron. “I went to this great little restaurant in Santa Monica last week,” Worf intones in his distinctive basso profundo voice. “The food’s great, and it’s affordable, too.”

Trekkies need not fear that the show’s writers have gone into orbit; the speaker, in full Klingon prosthetics, is actually actor Michael Dorn, taking a brief break from his morning’s work on Star Trek: The Next Generation. Behind his imposing frame, cinematographer Marvin Rush [ASC] is directing the crew on Paramount Pictures’ Stage 9 through a subtle series of lighting adjustments.

The scene at hand, Rush notes, will set the tone for an upcoming episode titled “New Ground,” in which Worf confronts the responsibilities of fatherhood. Although the sequence is fairly simple — coverage of a conversation between Worf and his human mother — Rush is taking extra care, and he explains why: “On a show like this, time is the most precious commodity,” he says. “It’s also the enemy. I’ve got plenty of equipment. I’ve got plenty of personnel, I’ve got plenty of money being spent to get the job done, but the clock is always running. For that reason, you’ve always got to consider the relative importance of the scene at hand. This scene basically sets the stage for the episode. So while there’s not a whole lot of movement in this scene, it’s very pivotal because it establishes what the problem is. I take that into consideration and if I have to choose I put more energy into the scenes that have to be just right. Not that anything’s a throwaway, but there are scenes where you just look at your watch and it tells you what to do.”

Rush admits that the schedule is grueling. Cast and crew can generally expect to gather for a 7 a.m. call and not finish the day’s work until 7 or 8 at night. Days of 12 hours or longer, five times a week, can take a considerable toll, but Rush insists that creative drive, combined with a sense of humor, can serve as an effective antidote to mental and physical fatigue. “We do ten months of this, and I think the battleground is inside your own emotions, your own head, your own spirit,” he muses. “It’s hard on families, it’s hard on the crewmembers, and you have to be sensitive to the basic fact that people get tired. The most important thing for myself is to keep a really positive attitude, a real sense of excitement about the work and a commitment to artistry. I’m certainly not finished learning how to do this job.”

That work ethic seems to have permeated the entire Star Trek hierarchy, from its late admiral, creator Gene Roddenberry, to its industrious ensigns. Currently in its fifth season, Next Generation has just kept improving, setting new production standards for televised science fiction while adding viewers with each new episode. The plaudits have been earned the hard way; after all, Roddenberry and Paramount Pictures gave themselves a tough task in attempting to resurrect the most beloved science-fiction series in television history.

“[Executive producer] Rick Berman said something a while back that was right on the money. He said that what we’re doing, if we’re not careful, can look very, very silly.”

— Marvin V. Rush, ASC

“I’m actually quite amazed at the success of it,” admits visual effects supervisor Robert Legato [ASC], who, along with fellow supervisor Dan Curry, helps give the shows its futuristic zip. “It seems to get stronger and stronger every year. There’s a hard-core Trekkie audience and there are others who just tune in because it’s a different kind of show to watch. I have to give Marvin credit, because a lot of that is due to the look. The old show could look pretty setty and cheesy at times, and you really had to have a little suspension of disbelief to buy that they were on a planet as opposed to a stage with a cyc on it. And now Marvin and the art directors go to great lengths to make it look believable. You don’t necessarily have to be a science-fiction fan to like it or be entertained by it.”

Indeed, Rush was nominated for an Emmy this year for his work on an episode titled “Family.” The recognition was gratifying, especially considering that the cinematographer’s prior, visually striking work on the NBC sitcom Frank’s Place ended abruptly when the show was cancelled after one season. Although Frank’s Place was not widely seen, it was appreciated by a few who mattered: namely, Next Generation producers Rick Berman and David Livingston. When the pair began looking for a new cinematographer for their own show, they called on Rush, who had moved on to another NBC sitcom, Dear John. Rush prepared a tape of clips from Frank’s Place, but found that a screening was hardly necessary.

“We sat down and basically talked about Frank’s Place, and they knew episodes chapter and verse,” he recalls with astonishment. “They both could quote scenes! So when we talked about lighting styles, I really had a leg up because they were fans of my work.”

Rush admits that he doesn’t qualify as a Trekkie. When he accepted the job on Next Generation, he had never even seen the show; moreover, he had never watched a complete episode of the original Star Trek series. What he didn’t know has never hurt him, however; in fact, his lack of familiarity with Kirk, Spock and Scotty may work to his advantage in that he has never felt obliged to pay homage to the original Trek’s look. That imaginative freedom has allowed Rush to compose his own unique vision of the future, which hews to some carefully considered criteria.

“Rick Berman said something a while back that was right on the money,” Rush relates. “He said that what we’re doing, if we’re not careful, can look very, very silly. We’re riding through space in funny suits, in this funny ship, and we’re creating aliens. There are a lot of things about it that could come off as very silly. If you do a lot of really over-the-top things with lighting and photography, you can push it over into the comic-book realm real fast. So it’s important to believe that it’s real in your own mind. I assume that this is really happening; it’s not a comic book to me, it’s 100 percent real. That’s why I favor source lighting; if you play source, the believability goes up, because source is what you see. If you use really garish colors, which I have on occasion, you try to moderate them so they don’t look like a rock concert. God forbid it should look like a rock concert – that’s not the appropriate tone for this! We try to play things a little more straight.

“I avoid the use of handheld for that very reason; I love handheld, but it’s not right for the future. One of the rare times we use handheld is for a fight sequence, but we’ve shot fight sequences without any handheld shot. The future is more fluidic than that. We use Steadicam from time to time, but even there, I expect the Steadicam to have almost no horizon roll, to be pristine and almost indistinguishable from a dolly shot. It needs to be seamless; I’m portraying how the future looks, and it ought not to be ragged.”

Rush keeps these theories in mind on all of the various Enterprise sets, from the sick bay to the bridge. “The Enterprise is a fairly ‘up’ and inviting place,” he notes. “That way, when the ship has problems, we can show that by having the lights go dark or by using flickering lights or a flashing color of some kind when there’s an explosion. The ship is often in jeopardy, and if you start out with everything wonderful, and not moody, you have somewhere to go when things go bad. I have a non-filtered look on the Enterprise sets. When we’re on the ship, it’s clean; we use filters very infrequently. This approach provides me with some headroom.

“That’s not true for the crew’s quarters, though,” he adds. “Each person’s individual quarters has some personality to it. That might include filtration, it might include color. I also tend to do a lot of accent lighting in the quarters. Jim Mees, our set decorator, and Richard James, our art director, come up with terrific stuff, and I want to make sure that if they put stuff on the set, they get to see their work when it’s on the air.”

To expedite the process, Rush and his crew will often conduct a prelighting session in the mornings, or send an advance crew ahead to work out the accent lighting. That way, when Rush confronts a swing set or some other complicated setup, most of the difficult, time-consuming work is finished. “The objective is always to get as fat a look as you can in as little time as possible,” he maintains. “And my crew has worked with me long enough to know what I like. Very often I don’t do a thing to what they did, because it’s right on the money.”

The lounge scene in “New Ground” provided a good look at some of the innovative set pieces designed to help Rush achieve his favored look. The most striking props in the Enterprise’s lounge area are its intimate tables, which feature futuristic-looking, glowing surfaces that Rush can exploit for ambience.

“This is a pretty easy set for us to light,” he points out between shots. “The tables provide a lot of the illuminations. One of the problems is that up-light is not always flattering, especially to women. So what you try to do is to keep the feeling of that source; for the masters it’s not a problem, but when you go into coverage you try to cheat a little bit and take it down while bringing up the sources a little bit. You still want that up-light feel but you want to smooth it out a little bit, make it a little more complimentary, especially for the women. For the men I do it a little less maybe, because the up-light is good for them, it gives them character.”

To enhance the day’s featured character, Lieutenant Worf, Rush has worked out a scheme that emphasizes his strength while sidestepping the pitfalls created by the Klingon prosthetics. “Michael has very deep-set eyes because of the forehead prosthetic, and he has an appliance on the bridge of his nose that makes it stick out,” he observes. “So his eyes are isolated, and in order to see them you have to use an eyelight – what we refer to as the ‘Worf light.’ I also try to use low angles and a little bit wider lens for Klingons to give them a strong, bold, towering presence.”

Rush emphasizes that he tries to fit his photography into the parameters inherent to the individual sets. “I try to establish something in a wide shot that gives the viewer a feeling and a flavor, based on the set design. You can’t light away from the sources because they’re part of the look of the set. I try to let the set dictate a lot, and I like the scene to dictate quite a bit as well. If there are no sources established in the scene, then I create some. The bridge is an example of a set that’s very ambient; it’s got this big dome over it, and it dictates a fairly ‘up’ look. I could do it ‘down,’ but I think that would be lighting away from what the set does.

“I essentially try to create a lit environment so that all we’re doing is making very small adjustments. I think Eastman’s 5296 film stock really helps in that regard — attacking the set as an entire piece, as opposed to creating lighting setup after lighting setup.”

While Rush’s various rules of thumb have helped make Next Generation one of the most visually distinctive shows on television, they occasionally cause him Jupiter-sized headaches. The main source of his anxiety has generally been the reflective black plexiglass panels that line many of the ship’s corridors and set pieces.

“When I first came onto the show, I took one look at the instrument panels on the bridge and realized that I was in the middle of a cameraman’s worst nightmare,” Rush chuckles ruefully. “There are a lot of reflection problems because it’s a hall of mirrors in the background. We just don’t accept reflections of equipment, lights, microphones or any of that stuff. It’s a point of pride, and there have been very few occasions when they’ve gotten by us. But it took a bit of time to figure out how to beat the reflections. We have so many reflective surfaces on the sets that if you put up a light and you have to put up four flags, it opens up a whole new realm of problems; the flags mounts are shiny chrome, and you have to black-tape the chrome of the C-stands. It’s almost as if it doesn’t work anymore because you have to work so hard just to put one light up.

“When the camera is directly reflected,” he says, “we can take [the camera] down so it’s very dark. So even though it’s in a reflection, because it’s dark and the characters are light it’s not seen. The panel is in the background, and what little reflection that remains is masked by distance, brightness and foreground action.

“The corridors, on the other hand, have black plexiglass panels that reflect all the way up and down, so all the lighting has to come from outside the set – or you can put a tiny eyelight on the camera. You have to find a way to make it look good, but you can’t put lights anywhere on the set.”

To counter some of the difficulty, Rush and his crew have tapped their collective ingenuity. “We’ve created some equipment, such as long, 2 ½-foot snouts for 750 soft lights — they allow me to shoot a soft light and not contaminate the set. I didn’t invent them, but we’ve built a few. If you have one very long snout, you can tailor the light to do the job. We have them for 4Ks and 2Ks as well. Part of the challenge and creativity of this job lies in finding ways to modify and design equipment.”

Rush’s brainstorms are sometimes foiled by the script — or by a zealous director. “Some of the directors like to do 360-degree shots, and I think any cameraman, I don’t care who he is, finds that the job becomes infinitely more difficult when all of his hiding places are taken away,” he says. “I get a certain amount of satisfaction out of finding unforeseen hiding places – working from up high, or in front of furniture. I haven’t had a shot yet that I couldn’t do; that’s not to say that we haven’t modified the shots a little bit or made some adjustments to make them workable. Sometimes, I’ll let a director know that I can get the shot, but also that if he wants it he’ll have to pay for it with time. Frankly, though, I often imagine myself in the director’s position, and I just don’t want to hear someone telling me ‘it can’t be done.’

“Very often, the directors have a very clear idea of what they want to do with the camera, and we do it their way,” Rush submits. “With the lighting I’m usually given more range. I’m rarely given notes from the directors about lighting. When planets are involved, I try to get a hook in my mind from the script as to what this planet might look like. If there isn’t a very clear look described in the script or if I don’t get a hook from it, I make one up and then I try not to repeat myself. I might have an idea, but if a director goes a different way, I need to conform my objectives to his point of view. It’s not always a marriage made in heaven, but very often it is. I believe my job is to make the various directors happy.”

The director of “New Ground,” industry veteran Robert Scheerer, confirms that the director/cinematographer relationship on the show is clearly defined and a major key to getting good results. “The director does get totally involved with camera placements,” he maintains. “I basically come in with a plan about where to put the camera, where to move the camera, and where to cut. That doesn’t mean that Marvin isn’t very creative and doesn’t offer suggestions. The relationship between the director and cinematographer is very important. It can make the experience very unhappy if you don’t have a good relationship. If the combination works, you get so that you’re talking in shorthand after a while, which is a great help.

“On this show,” Scheerer concedes, “the look pretty much is dictated by Marvin. He sets the style; the directors are the guests when you come right down to it. The actors, the cinematographer and the crew are the ones who are permanent, and the general tone of the show really has to be set by the director of photography. This show’s a little harder than most because there’s less furniture and fewer props — no glasses, no cigarettes. You have to think it out a bit more because the sets are very Spartan, and the activity is very focused. You’re really depending more on the word and the actor’s use of the word — and of course invention with the camera.”

Rush is quick to point out that Star Trek is an assignment that most cinematographers would jump at. “I don’t want to give the impression that all of the variables are somehow limiting,” he says. “Star Trek is a wonderful opportunity; it’s very much a cameraman’s show. I did sitcoms for a long time, and I tried to do my best on those, but no matter how hard you try they’re just not going to get noticed for photography. With this kind of show, the audience is looking for it, which also means that I can feel like I’m under a microscope. If I don’t deliver pretty good work, I’m going to get a lot of boos.”

To avoid the wrath of armchair cinematographers, Rush and his crew are consistently on the lookout for novel ways to create a sense of adventure. On “New Ground,” the Trek team employed a shipboard gimbal to convey the impact of a “soliton wave” that smashes into and rocks the ship. “This gimbal device is like a pendulum tripod,” Rush explains. “You put it on a ship, and the boat will move, but the horizon will stay level because the pendulum will move with the horizon. We hooked it up with the video tap and then ‘roiled’ the ship, with the actors falling one way and the other. You’d think it would be really hokey, but on film it worked out quite well.”

For an episode last season in which LeVar Burton is transformed into a lizard-person, Rush worked with blacklight provided by a company called Wildfire. “LeVar’s character, Georgi LaForge, was on a planet, and a disease he had unwittingly contracted in the past finally became active in his body. The final conversion was this weirdly-veined creature that was basically invisible; you could only see it in ultraviolet light. We had 2,000-watt UV lights and fluorescent ultraviolet blacklight tubes working, hidden in nooks and crannies. It was very complicated stuff, and the whole show was hung on this effect. UV is interesting because you can’t really meter it; you have to use your own judgment. In the end, it was very effective. LeVar was wearing a rubber suit which had blue veining designs on it, and they really did glow in the dark. You had to have the lighting sort of subdued for them to work, but that was the whole point; the planet was very, very dark.”

During another memorable shoot, Trek’s production team created a botanical environment that took up nearly half of Paramount’s Stage 16. Rush recalls the setup with admiration: “We shot the whole thing with a Louma crane, including all of the coverage. We did fifty setups that day, all with the Louma crane! We split the set and ran pipe-track down the middle, which we then covered with carpets of grass. By using the Louma crane on this pipe-track, we could get the camera anywhere; the advantage was that we didn’t have to use sticks, which would tear up the grass. We could do moving shots with the Louma crane and have only one guy in there; the focus-puller worked further from the lens. As a result, the set stayed pristine, and it was as good the second day as on the first.”

Occasionally, Rush gets the chance to work with actual outdoor locations, although he estimates that the opportunity presents itself only four or five times per season. Although Rush relishes the chance to stretch himself a bit, he feels that the strict limitations of a television schedule preclude the kind of perfectionism granted to cinematographers who work on feature films. “I believe that the best cinematography for exteriors has more to do with time of day than anything else,” he maintains. “Great cinematography is the ability to control the time of day. On a television schedule, you just cannot do it. I can almost never really get what I want on location. You end up trying to trick the sun by putting a silk up. Some of those things look false to us. We did one outdoor shoot where we got there at 6 a.m. when the sun came up, but it didn’t come up; the clouds were down to the tops of the mountains around us and it was absolutely heavy overcast. And those shots intercut with scenes we shot in blazing, dead-center noonday sun! We did a couple of things to compensate. We overexposed the film a stop to add some contrast in the morning stuff. We didn’t use much diffusion. Then in the afternoons we used soft-cons and we underexposed a little bit. In those kinds of situations you feel great pain, because you know that if it was a feature it would have been scheduled differently.”

Rush was proud of his exterior work on an episode called “Silicon Avatar,” in which a huge crystalline entity menaces a colonized planet. “On that show, we did a slide diffusion of a very dark blue filter to create the idea of a shadow coming over the sun,” he recalls. “Obviously, we couldn’t create a shadow over the sun because we were seeing hundreds of acres. A camera operator who’s a friend of mine has a slide diffusion that he got from a commercial. On the cut where the shadow comes over the sun, we slid it through the lens, and it went from cold to extremely cold – really, really dark, saturated blue. It created a reasonable illusion, and it worked pretty well. As usual, the very best shots were done at twilight, when there’s a real contrast, a low sun angle, and a little dust in the air.”

Aside from the practical challenges caused by the show’s schedule, Rush must also tailor his work to fit the needs of Star Trek’s special effects wizards. These considerations can affect his framing and lighting choices but Rush has developed a cooperative and constructive rapport with the show’s effects men.

“The optical effect work is primarily the technique of just locking the camera down for the part of the shot that’s in optical,” he relates. “The optical is then laid in on top of the shot. The real magic is on the postproduction side, but the tricky part is where you’ve got something happening in real time, where an actor is performing to something that is going to be on the other side of a split-screen, which is not there. Here’s an example: the camera starts on a doorway, pans over to the transporter pad and locks. The actor who’s walked through the door is performing to the person who’s appearing. The second actor rushes in from the side, hits the mark and immediately is there. They then freeze-frame on that split screen, pull up and essentially create it in real time. So there’s a very thin little moment of time to get the person in, get enough for the freeze, and then come out of the split-screen, unlock and move again. That gives you the illusion that someone is actually materializing on the pad, but it’s literally just sleight-of-hand

“I don’t do this myself,” he emphasizes. “We have two visual effects teams that are their own departments. They plan it out and then come down to the set and help me figure out how to do it. One of the typical problems is that you can’t have a shadow cross a split-screen, because if it does, you can see the magician behind the curtain. Sometimes the lighting approach to a set is constrained by the optical that’s being done. And sometimes it’s not for the better of the lighting, but it’s necessary for the optical to work.”

The show’s visual effects have received stellar marks from viewers, thanks to the efforts of the two teams. Rob Legato and coordinator Gary Hutzel comprise one unit, while Dan Curry and his second, Ron Moore, handle the show on an alternating basis.

Legato joined Star Trek after working on the second season of another resurrected ’60s hit, The Twilight Zone. Unlike the new Trek, however, The Twilight Zone failed to catch on with today’s audience and was cancelled, leaving Legato to freelance until he got the call from Next Generation. “They reviewed what I had done, and I had what they were looking for: experience with shooting effects on film and then transferring them to tape,” Legato says. “The original concept of the show was not that effects-heavy; it was going to require something like 10 new shots a week. It’s ended up being 10 times that; some weeks it’s close to 100 effects shots, and it averages between 60 and 100. There are actually very few light shows as they originally intended.”

Curry, who joined the show during its conceptual stages, notes that he was originally called in to storyboard a series of generic ship shots to be produced by ILM. “The initial idea was closer to that of the old show,” he confirms. “ILM would shoot a certain number of shots to cover the needs of the show, like the Enterprise right to the left, left to right, coming at the camera, heading away, and so forth. Then they realized that wasn’t going to work.”

“The pilot had 50 shots in it, and all of them were very specific to the story,” says Legato. “Then when we went to do the very first episode, there was a mystery ship, and some other unusual things, and the regular shots didn’t work. Now we basically tailor-make each episode. There is some use of stock, but we pretty much base each show on what’s needed.”

That working method has been both a challenge and a source of humor, according to Legato. “One of the early scripts had the Enterprise going to the end of the universe,” he says. “The end of the universe can’t be described because it can’t be understood, but it still has to be budgeted and shot, and it’s got to be done in four weeks. I mean, the end of the universe is not a stock shot! Another tall order had a beam from a planet knocking the Enterprise end over end at warp speed. One of the producers said, “Do we have that as stock?’ No, we don’t have that as stock! I think they would have remembered!”

At this point, Legato says, the effects crews have created close to 500 ship shots. “Each show has its own timings, where something happens in three seconds, or ten, and it almost eliminates stock shots. Fans of the show recognize when we use the same ship again. We’ll take an old ship and maybe color-correct it differently, light it a little differently, and shoot it from a different angle. Some people still notice, but they’re not around when we’re budgeting! It’s still a television enterprise [Ed note: no pun intended] and you want to put the money where it’s best used and more entertaining.”

The effects teams are generally bound to a two-week schedule for each show, which usually takes a total of six weeks from the first day of footage to delivery. Legato reports that he usually can’t get much done until a show it cut. “From the time a show is cut to the time I have to deliver the effects is sometimes ten days, sometimes eight days, or as many as thirteen. We plan as much as we can beforehand, but we usually have to wait to see how the effects shots are going to be cut in.”

To speed up that process, Star Trek’s postproduction team at Unitel in Hollywood has taken advantage of the AatonCode system, which is used in conjunction with Panavision Panaflex cameras. A time code is added to both the film and the sound rolls during filming via Aaton’s “video linker” device; in postproduction, the code is recovered from the film and used to sync the audio with the visuals, making the entire exercise smoother and faster.

Despite such innovations, Curry reports that some orders stretch the visual effects teams to their limits.

“In an episode we just finished, called ‘A Matter of Time,’ we had to show the Enterprise cleansing the atmosphere of a planet that was experiencing the equivalent of a nuclear winter,” he says. “We were trying to control the behavior of a lot of unusual materials, like dry ice and liquid nitrogen. To do something on that scale, with our schedule, can be interesting.”

When not consulting on Paramount’s stages, the effects teams are based at Santa Monica’s Digital Magic, after previously working at The Post Group. One of the main reasons for the switch was that Digital Magic offered to hook up a two-way microwave link that connects the sound stages to the effects bays. “Instead of driving to the studio to supervise one shot, like a burn-in or something rather simple, you can essentially do it over the phone,” says Legato. “So we can plus in the video tap and basically satellite it over to where we’re working and see it on the screen. It works in reverse as well. It’s literally become ‘phoning it in.’ It’s as much fun as technology can offer.”

Legato is also a proponent of the newest digital technology for effects, which he cites as one reason the crew is able to keep to its rigorous schedule. “Everything we shoot on the show is generated on film, mostly to maintain the same look. I shoot everything at 24 and try to make it match so it still feels like film quality when you go from Marvin’s footage to my footage. Then we transfer that to tape and do all of our work on D-1. It starts out as digital tape and never goes down a generation after it’s transferred. Only when it gets cut back into the show does it go back to analog. It’s as pristine as we can make it. There are a lot of advantages to D-1 as opposed to the way we used to do it. Now we can make some settings, say color settings, give it an additional glow, record those settings, come back 10 years later, press those numbers in and match into it identically. You just turn the knob to number 7 and it’s going to be that way week after week after week. That is a great innovation for us.

“We transfer footage at CIS in Hollywood, where they have their own modified registered Rank, and it gets transferred to a Sony D-1 machine,” he continues. “It goes from an Abekas A-64 that gets downloaded to a D-1 tape, and that D-1 tape goes to Digital Magic. In the digital bays we have two A-60s, which are basically scaled down A-64s. The A-64 has all the matte programming and things like that, and the A-60 is a smaller version of that. We have two of those, two D-1 machines, the A-64, and then the A-84, which is the big digital switcher that allows us to do layering. It’s a fairly complicated setup, and since it’s digital you can memorize that setting. So if you have to do twenty minutes of, say, a monster scene, or a flashback scene, then you do kind of a convoluted way of printing it and adding highlights, or crushing blacks, or adding tint or whatever – you can keep it very consistent by just dialing up the same thing. It’s not quite like an analog, where you have to set it by eye.”

In addition to the more standard tricks, Star Trek’s legerdemain department has also pulled out the stops from time to time. For the spectacular shots of the Enterprise “stretching” into warp speed (seen weekly during the opening credits), the team has borrowed the “slit-scan” process introduced during the Star Gate sequence in 2001: A Space Odyssey. “ILM did three original shots where the ship stretches out, and we did two for an episode that I directed,” says Legato. “You photograph the artwork through a slit that scans from the left edge to the right edge. Basically, in one frame, if you shot it this way, it would scan on the whole piece of artwork. You take that and introduce a camera move so that as the slit is moving across the artwork, the camera is moving back at the same time. It appears to take the object and tip in perspective; in the Star Gate sequence, it looks like it was shot with a 10 millimeter lens and stretches out into infinity. Then you take that, and besides the slit moving you move the artwork as well, so now you have this thing that’s running through at what appears to be a rapid rate.

“That’s a two-dimensional way of doing it; we took that idea and basically projected a slit onto the Enterprise. In any one frame it would go from one end of the Enterprise to the other; if the camera didn’t move, it would just look like a regular shot of the ship. But the camera starts to pull back as the slit’s going across, so the front end of the Enterprise looks normal and then the very end of it is stretched. Bu the time the camera gets twenty feet away, the slit is by the nose. It appears to stretch, like a rubber band expanding and then catching back up to itself. This process can only be used for a couple of shots, though; it’s very expensive.”

Legato and Curry, like Rush, claim that they are not true Trekkies, but they are well acquainted with the fanatical fan base that has made the show a success. Legato claims that their psychic presence adds no pressure to the job, but he notes that the devoted legions do keep in touch. “We still get letters if we make a mistake,” he says with a sardonic chuckle. “I got one letter because I had the phaser ray coming out of the wrong hole! Well. We do hundreds of shots every week, and I’m sorry if I got it coming out of the wrong hole! The letter went on: ‘Other than that, I congratulate everyone on their ordinarily fine work.’”

This article originally appeared in American Cinematographer, January, 1992.