Star Trek 50 Part VIII — Undiscovered Cinematography

The cinematographer discusses his collaboration with director Nicholas Meyer on this interstellar adventure.

This is the eighth entry in our 12-part retrospective series documenting 50 years of production and post on the Star Trek franchise. In this archival interview, Hiro Narita, ASC describes his approach to shooting the sixth feature film to star the TOS cast.

Narita Leads Enterprise Camera Crew

For cinematographer Hiro Narita, working on Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country was an entirely different experience than shooting his last project, The Rocketeer. On The Rocketeer, Narita had the time and money to make that lavish period fantasy; not so on Star Trek VI, where there was less time and less money. While The Rocketeer’s shooting schedule had been an ample 19 weeks, Star Trek VI’s was a mere 10, very tight for a film of this scale. But the fact that Star Trek VI was a tenser shoot than The Rocketeer may bode well for what is supposedly the last adventure for the crew of the starship Enterprise — sometimes the more rigorous the experience, the better the result at the box office.

Narita’s involvement in the project began with a phone call from Steven Jaffe, one of the producers of Star Trek VI, who has been a friend of Narita’s since hiring the cinematographer to shoot some footage of the Golden Gate Bridge for Who’ll Stop the Rain 15 years ago.

Having just finished shooting The Rocketeer — and before that, Honey, I Shrunk the Kids — Narita was somewhat concerned that most producers would look at his reel and see a man who could shoot special effects extravaganzas and nothing else, despite the fact that The Rocketeer was a period fantasy and Honey, I Shrunk the Kids was really a contemporary comedy with science-fiction overtones. “Even today, I’ll get questions like, ‘Do you think you can light a woman?’” he laughs. “Before, when I did Never Cry Wolf, the only scripts I received dealt with animals. Now that I’ve dealt with giant scorpions, Spock and the Rocketeer, some producers cannot translate that into other stuff. I don’t want to be typecast.”

Narita’s fears were somewhat assuaged when he learned that the film was going to be directed by Nicholas Meyer, with whom he’d wanted to work since he saw Time After Time. “I read the script for Star Trek VI — rather reluctantly — and I liked the story,” Narita recalls. “So I decided to meet with Nick. I was very open about not having seen the show or many of the movies; I saw the very first one, and I must’ve seen II on television, and that’s it. I told him I didn’t have enough knowledge to launch on the project, but he liked the fact that I wasn’t a Trekkie and didn’t have a lot of preconceived notions.”

Each of Star Trek’s cinematic voyages has been shot by a different cinematographer hoping to change the look of the all-too-familiar Enterprise bridge, corridors and transporter rooms. Narita’s aspirations were no less grandiose, and he and Meyer had discussed the look they hoped to achieve prior to filming: “Nick showed me two films, Alien and Outland. He liked that kind of look, which depended heavily on art direction and color, and he wanted the spaceships in this film to have a submarine feel.”

The task sounded simple: just build sets that would accommodate the new ideas, as Meyer did when he revamped the entire look of the film series for Star Trek II. However, Paramount’s conservative fiscal caveat made a huge dent in Narita’s plans. “Since the ship has been taken out of storage and made to function for this mission, I thought it should have a patched-up heavier, more claustrophobic look as compared to the open, well decorated set we had to work with, but that was beyond my control,” Narita says. “I knew the production designer, Herman Zimmerman, was brought in because he’s done other Star Treks, and because he knew how to deal with existing sets and so on, but I felt he wanted to be very faithful to the look that had already been established. So I decided to challenge myself to see what I could do within all these limitations. The challenge on my part was to create something new, or at least slightly different, partially using existing sets. In some cases, I succeeded in making it very different, in others, I didn’t, maybe partially through a lack of imagination on my part. Sometimes I was overwhelmed by how little I could do.”

Narita very quickly found he was straitjacketed most by the look of the Enterprise bridge built for Star Trek V, which featured the black instrument panels its director, William Shatner, had demanded for that film. “I wanted to approach it differently in terms of lighting, but all of the existing practical lights were beyond my control. They changed the color a little bit, and some of the graphics, but structurally, it was the same. I felt that to create the shafts of light necessary to convey the submarine quality Nick wanted, we needed a certain kind of value and tonality in the background walls, which was difficult to achieve using an existing set.

“I lit as spottily as possible,” Narita continues. “I didn’t want to use too much smoke on the Enterprise, because I didn’t want it to end up looking too much like the Klingon starship. For that reason, I decided to keep the look of the Enterprise pretty clean, but with a little more contrasty lighting. To make things even more complicated, we were forced to use the Enterprise bridge to double for that of Sulu’s command, the Excelsior. In that case, we just changed the colors on the set. To save money, we also used a repainted corridor set from the Next Generation series.”

Shooting aboard the Klingon vessel proved more challenging photographically than shooting on the Enterprise, primarily due to an exciting assassination sequence with a bloody, zero-gravity aftermath. “I wouldn’t say we had a lot of elaborate camera movement on the Klingon ship,” Narita cautions, “but we did have more cuts per scene to create tension and drama. For example, we spent three days shooting the assassination scene, and our second unit shot a lot of pickups as well.”

After the mysterious, unprovoked assassination on the Klingon vessel, Kirk and McCoy beam aboard to discover a scene of chaos and horror, with Klingon blood hovering weightlessly above the victims. To create the effect of weightlessness, the actors were primarily flown on wires, a technique Narita was quite familiar with in the wake of The Rocketeer. “We had to remove the ceilings from the sets for many of these shots, but fortunately, most of the sets we used in this sequence were built for the film. Part of it took place in the transporter room, which is a set we borrowed from The Next Generation and painted differently. For some shots where we didn’t have to see the actors’ entire bodies, we’d place them on a teeter-totter arrangement which looked almost like a small camera crane, then counterweighted the opposite end and moved it slightly to create a floating feeling. We augmented the wire- and counter-balanced crane work with slow-motion photography, which helped create the illusion of weightlessness; we shot this sequence at about 40 frames per second to slow down the actors’ body movements just slightly.”

Unfortunately, Narita found that his suggestions on how to hide the wirework were not always heeded by the film’s production designer. “I knew that the plainer the wall, the more noticeable the wires would appear against it, so I suggested that by darkening the wall and adding a pattern to it, we could create enough visual confusion that the camera might not see the wires. Sometimes they followed my suggestions and sometimes they didn’t. In any case, it’s basically a matter of having ILM remove the wire optically using computer graphics.”

While Narita was accustomed to combining practical and optical effects, he was frustrated by the need to light a scene for principal photography, then relight it to accommodate special effects. “The scene has to look the same, even though we might be multiplying the amount of light. It’s not an easy thing to do. A scene might be lit with a couple thousand watts to begin with, and then, all of a sudden, I’m dealing with 5Ks; how do I keep a similar look? If the color temperature’s different, how do I make that footage match as closely to the original as possible? It’s never the same and I can only recreate it halfway decently on set. I know eventually we can change it with the timing, but then everything else changes. There were many shots like that, which made things tough. Fortunately, ILM was actually able to readjust the contrast and sometimes burn in areas that were too bright, which was literally like printing a series of stills.”

Those familiar with the technical history of the Star Trek films will no doubt be surprised to learn that there wasn’t a single blue screen shot to be found in Star Trek VI — instead, black screen was used outside the windows of the Enterprise, where space effects would later be added by ILM. “It only became tricky when people passed in front of the screen,” Narita relates. “In that case, the fore- and background people had to be in reasonably sharp focus, and that meant we needed a lot of light. That was very time-consuming, so we tried to avoid overlapping actors with the screen.”

In addition to maintaining the status quo with the look of the Klingon ships and the Enterprise, Narita learned that many of the actors from the TV series preferred to appear unaltered by the passage of time. Unfortunately, the crew of the Enterprise are not the same people they were when Star Trek took its maiden voyage in 1966. Meyer stepped in when necessary to smooth things out. “The actors wanted to look great,” Narita says candidly, “But I lit them in the way the story required. I was constantly concerned about their appearance, but at the same time, my belief was that if a character was lit the same way throughout the film, no matter how good his performance might be [the lighting] might help the actor or the picture. William Shatner felt that he looked best in certain lighting situations and sometimes I took his suggestions and other times I didn’t. I’m not sure how understanding he was, but he accepted it.”

Narita was fair in his decision to light for the drama, extending this approach to include those who were heavy prosthetic makeup as well. “Those actors may not look too attractive, either,” he smiles. “As we went along, we tried to adjust the coloration on some of the characters slightly. Sometimes, in a warm ambient, the Klingons looked a little too red, so the makeup people had to adjust it or I’d adjust my lighting here and there. On Star Trek, I found working with the makeup was much easier than on The Rocketeer, where Lothar had to be believable as a real person. At least for this film, they didn’t have to look human.”

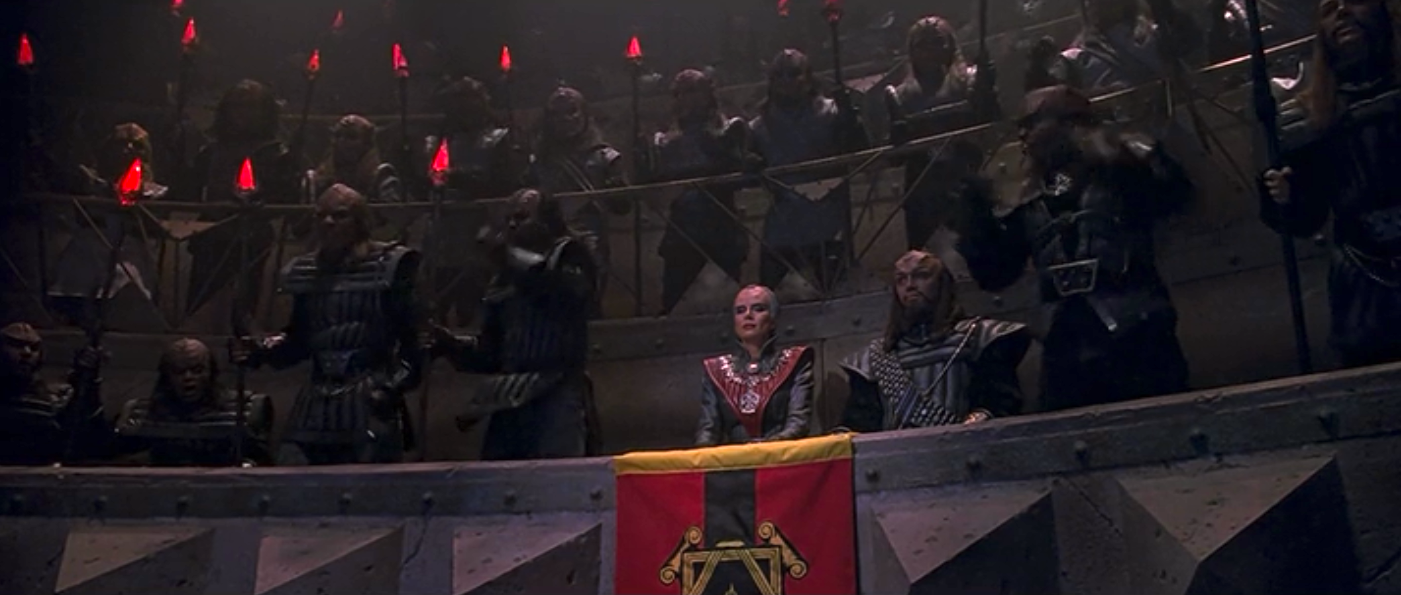

While he did have to contend with some existing locations and existing sets for the Klingon Bird of Prey and Enterprise interiors, Narita is quick to point out that Star Trek VI did boast some unique sets that were completely unlike anything previously seen in the film series. Foremost among these was a Klingon courtroom built on Paramount’s Hollywood lot, used expressly for the sequence in which Kirk and McCoy are tried for the murder of a Klingon leader. Overall, Narita found the sets much smaller on Star Trek than on The Rocketeer. To make the courtroom set appear larger, he created a hot spot at its center, where the accused sit beneath a brilliant light which radiates outward before falling off dramatically at the outer edges of the frame; the Klingons in the audience appear as mere silhouettes in seats, thus hinting at greater numbers beyond. To further enhance this illusion, the trial sequence will begin with a bird’s-eye view matte painting of the courtroom.

“This was the most exciting sequence in terms of both the storytelling and the visuals, so I tried to achieve more for less,” Narita explains. “Theoretically, we wanted to create the feeling that this arena was many stories high, but we didn’t really have any space. The courtroom set was circular, and in this instance we didn’t have to confirm to any traditional style or look. The center area was at ground level and measured maybe 40 feet by 40 feet; then it gradually widened as it went up to form an amphitheater that was about 80 X 80, with lots of Klingons sitting in these angled rows of seats.

“I was able to create some fairly moody lighting in that scene,” Narita adds. “We wanted to make it as dramatic as possible. To create the strong shaft of light in the center of the courtroom above Kirk and Bones, we used an HMI malipso light aimed straight down through a piece of safety glass — just in case something were to happen to the lightbulb. The HMI was blue daylight and I didn’t try to correct it, I kept it blue. I let the set be two to three stops overexposed in the center, and everything else was lit very dimly with a warm amber 103 gel. The judge was an albino Klingon, so he had a very pale face and white hair that was almost hidden under a large black hooded cape. Nick wanted this white face only to become visible occasionally, so I aimed a little spotlight at him from above so you only see the judge’s nose and forehead when he leans forward into the light. That was the kind of thing I really enjoyed on this film.”

Because of the tight schedule and the relatively large size of the courtroom set, Narita used a timesaving technique he’d employed for The Rocketeer’s South Seas Club sequence: “I used electronic dimmers on the lights for certain shots so I could control the lighting during the shot or change the intensity, though you certainly wouldn’t notice the lighting change. I didn’t use this technique as extensively as in the nightclub in The Rocketeer, but it was useful whenever we change the camera angle. As in Rocketeer, I was able to turn off certain lights and turn on others very quickly to change the lighting for the opposite angle.”

After the trial, Kirk and Bones are sentenced to hard labor on an inhospitable planet that bears more than a passing resemblance to Siberia. The interior of the Klingon prison camp was actually shot on an exterior location in Griffith Park’s legendary Bronson Canyon; the canyon is still recognizable as the Batcave from another TV show that became a cornerstone of ’60s pop culture. In this context, it is perhaps even more appropriate to point out that Bronson Cave was also a favorite location for Universal’s Flash Gordon serials, which were Star Trek’s true ancestors.

“Theoretically, the Klingon prison was supposed to be an underground mine, a large underground cave with a few tunnels,” Narita says. “It would’ve been too expensive to build it on a soundstage, so we had to deal with this fairly large interior/exterior set during our first week of shooting. They had a very high wall built which was supposed to look as if it were partially rock and partially ice, and halfway up the wall, there was a ledge where the guards could walk and check the prisoners. Most of the scenes take place in this large area, which resembles an underground prison yard. We had to work at night to give it the feeling of being an interior, but we didn’t tarp the set because we figured even if you saw the black sky, you’d think it was the roof of the mine.

“I didn’t want to see the film go completely dark and moody just for the sake of change — there were definitely some moments that shouldn’t be that way.”

— Hiro Narita, ASC

“We were able to dress the actual tunnels to look like mine shafts, but the problem was that we couldn’t drill any holes to attach our lights. There was no place to hide really big lights, so we had to devise some practical lights that looked like they could actually be in the shaft. We hid lights behind whatever rocks protruded every few feet, and the art department also built a series of support beams behind which we could also hide lights, so I didn’t mind seeing them in some of the shots. The miners had battery operated lights built into their face masks. We also smoked the set, which created some problems in the case of the mineshaft because it was open at both ends. We had to block the ends to contain the smoke. Keeping the smoky atmosphere consistent from shot to shot was tricky. I noticed a slight difference in the density of the smoke from angle to angle, but I hope no one else will. The overall effect is very dark and creepy.”

The exterior of the prison planet was actually shot on location in Alaska for part of an escape sequence montage in which Kirk and McCoy fly the coop with a couple of renegade aliens. The snowy terrain was familiar to Narita, whose fine work in similarly inclement landscapes can be seen in Carroll Ballard’s nature adventure, Never Cry Wolf. “Alaska was the only remote location we used for Star Trek VI,” Narita recalls. “The exterior was shot on a glacier with the so-called second unit and photo doubles of Kirk and McCoy. I’ve never seen a glacier like this one: the ice was at least 200 feet thick and the landscape it created was really unearthly, a really unexpected sight. We brought no lighting equipment with us; we were so far away from civilization that everything had to be helicoptered in. We couldn’t hand-carry anything between setups; we had to use the helicopter to move equipment because we were afraid we might fall through the ice. Since we had the helicopter with us, we did some aerial shots as well. All told, we shot for three days, and we could’ve used more. The only concern on the director’s part was to see if we could make it look even more otherworldly; the sky was still blue, so he wanted to make it a purplish color, which is a job for ILM.”

As our heroes make their escape, they are caught in an otherworldly snowstorm, a sequence which Narita found to be one of the more difficult to execute. “It wasn’t easy to create a believable blizzard,” he admits. “The sequence was supposed to be an exterior but we filmed it all on a soundstage. We used two types of plastic snow mixed together, one with very large flakes and another that was very powdery, both of which were supposedly okayed by the board of health. It looked very convincing to me, but it was difficult to control the amount of snow being tossed by hand or blown by airhoses manned by the grips up on the catwalks. Sometimes it drifted completely off-set before it ever came into camera range! I’d never worked with fake snow on this large a scale. To maintain continuity in the amount of snow from shot to shot was extremely difficult, so we’ll probably have to double-expose some more snow in.”

Narita soon realized that the fake snow had a tendency to get into the equipment. “For safety’s sake, we decided not to change magazines on the set. We had to take the whole camera out of the stage because we were afraid the fake snow might get into the film. Even weeks later, people were still finding snow in their socks!”

Star Trek VI was shot on Kodak in the Super 35 format with the intention of blowing the image up to anamorphic, a subject which is sure to stir up some controversy depending on which cinematographer you talk to. “I’ve only shot Super 35 before on commercials,” Narita admits, “so before I came on this project, I saw some films which were shot on Super 35, then blown up to anamorphic format. That particular system calls for as clean a negative as possible and a little more contrasty image. When you blow it up you get a bit more grain, but oddly enough, the image is less constrasty, so you need the contrast to begin with because you’ll lose some of it later. If you shoot anamorphic, you’re dealing with a larger negative area. Some people think that’s the better way to go: the image is much prettier and sharper and there’s less grain. The advantage of shooting Super 35 and blowing it up to anamorphic is that you can use spherical lenses and gain more depth of field. By using spherical lenses, you gain in the speed of lenses and you get considerably less distortion in the wide lenses; a 50 millimeter anamorphic lens will bend the image at the edges of the frame when you pan or tilt, something you don’t get with spherical lenses, and that same 50 millimeter lens will give you a shallower depth of field than using a 25 millimeter spherical lens with Super 35. The tradeoff with shooting Super 35 is that while you do gain grain, you also gain clarity of image because you’re using standard lenses; in terms of shooting, it’s so much easier. I don’t think that’s much of a tradeoff at all.”

In keeping with the need to maintain a higher contrast original negative, Narita used few filters during the making of Star Trek VI — a brave decision considering that the many alien environments must have been screaming for filters. “I used filters on my lights, but not on my lenses,” he says. “I may have used a soft effect filter for certain close-ups, once or twice, but that was it. I wanted to keep the images as clean as possible.”

While Narita shot all of Star Trek VI on Kodak stock, he feels that sequences such as the Klingon courtroom scene would have benefitted from the use of Agfa film, which he feels would have captured more detail in the shadows around the edges of frame. “I used Agfa on The Rocketeer, just for the South Seas Club sequence,” he recalls. “But when I mentioned Agfa to Paramount, they declined. For this particular film, I didn’t fight for different stocks because Kodak provided the contrasty look I needed. But on The Rocketeer, the South Seas Club would have looked so different if I’d shot it using Kodak stock, because Agfa is good at giving it the creamy look I wanted. There were a couple of scenes in Star Trek VI that could have used a softer, warmer, gentler look. I used 48 for exteriors in Alaska, and I used 8-perf for special effects. I was able to shoot the blizzard scene on stage using 96 because there were no direct cuts to our Alaska exteriors.”

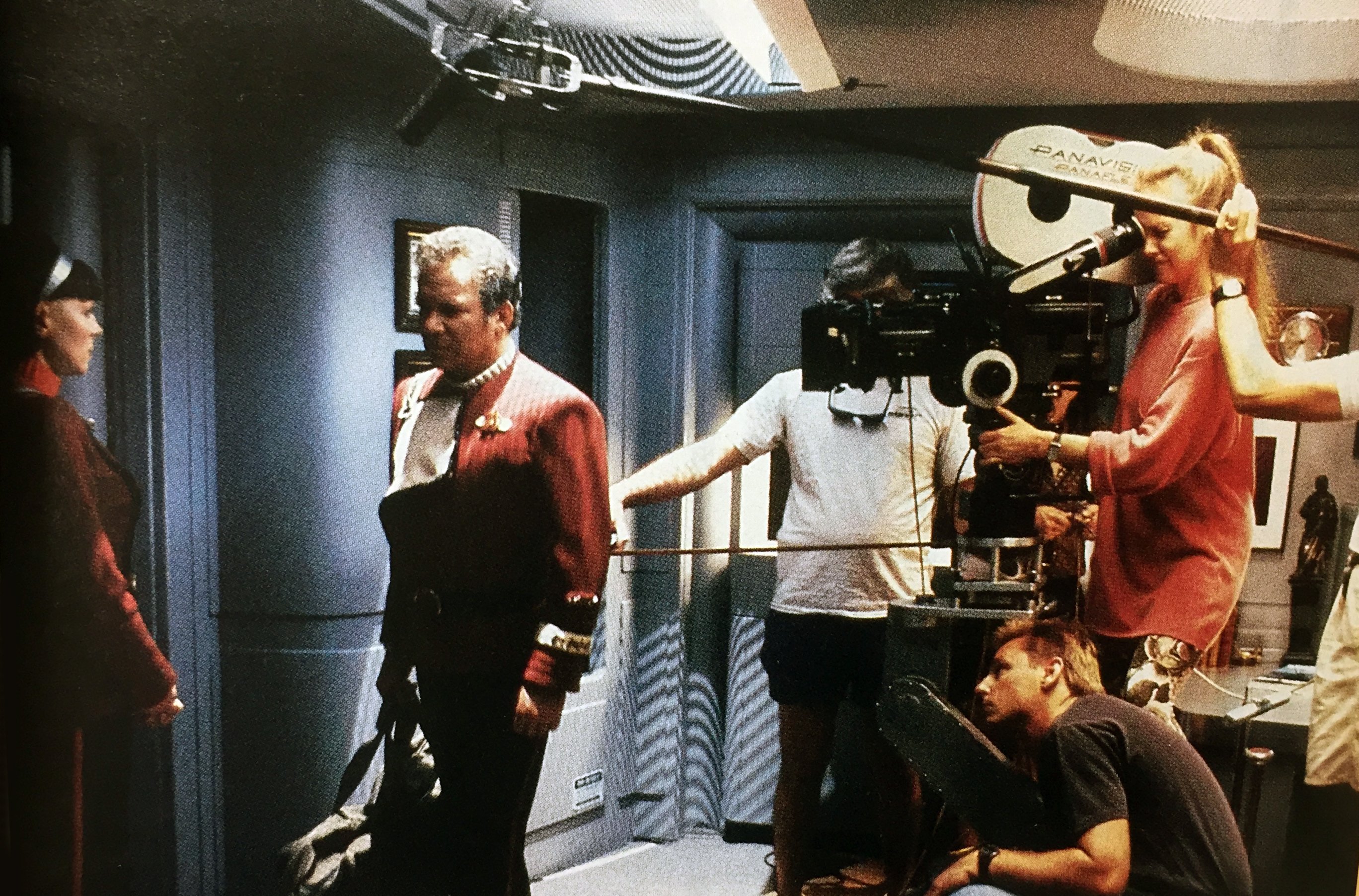

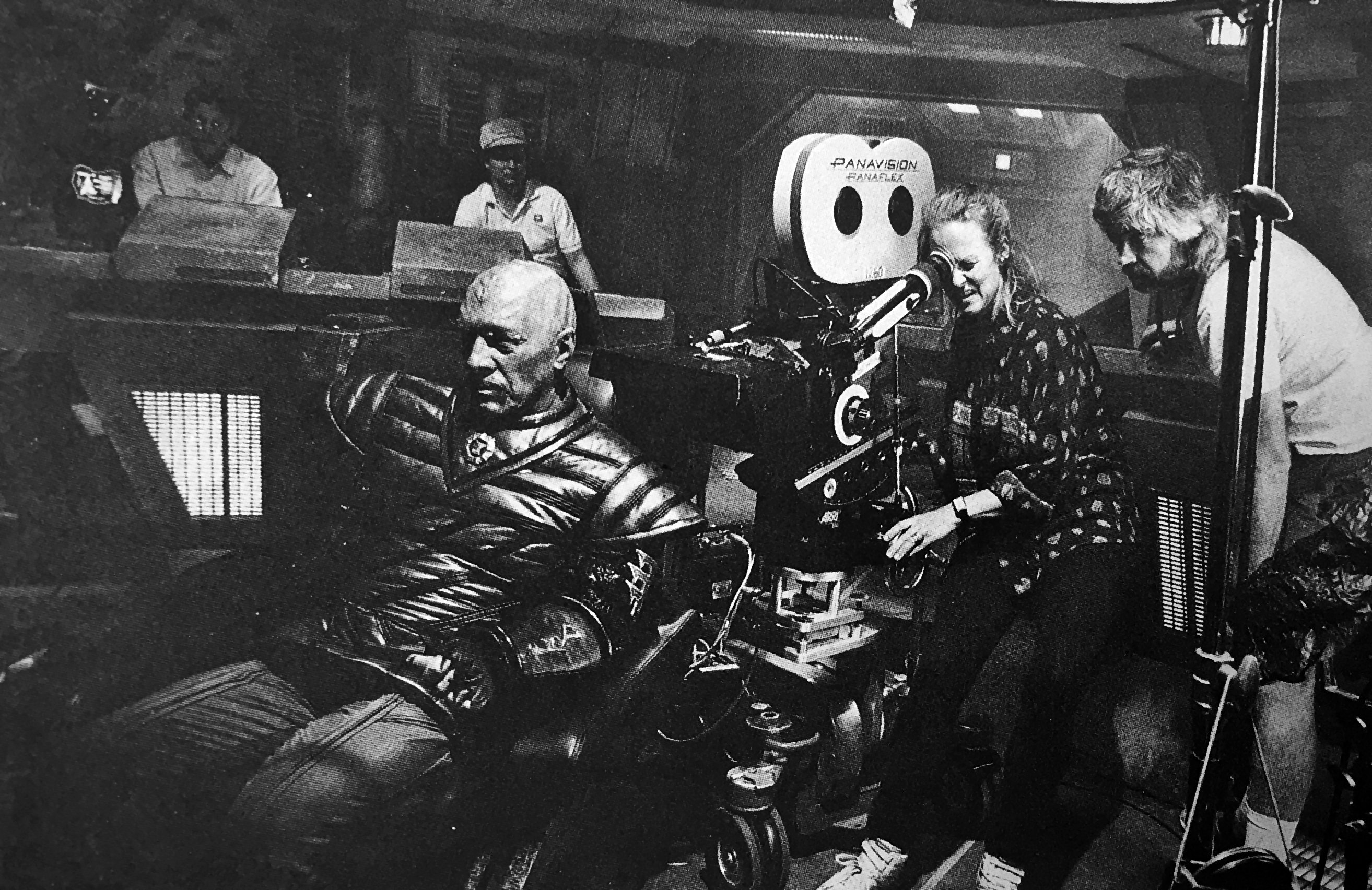

Narita worked with a different crew this time because the people he normally works with were unavailable. “My assistant was Rob Morey, whom I always like to hire first,” Narita says. “Rob is like having insurance; I know what he can do, so when I hire the operator, I tell them they already have an assistant. No one has ever been unhappy.” In addition to gaffer Robbie Rao and grip Ben Beaird, Narita hired one of the few female camera operators, Kristen Glover, who occasionally manned the B camera on The Rocketeer. “I met her when she was an assistant many years ago, and I knew she was one of the best assistants in the business, but I hadn’t seen her since she started to operate for Stephen Burum and Caleb Deschanel and occasionally shoot. She showed up when I was prepping The Rocketeer, and I decided to give her a chance. She was very good; her background is in painting, and mine is in graphics.”

Even as he’s shooting, Narita likes to think of the films he shoots in their completed form. Thus, he can look past imperfections in certain individual images if he can see how they might flow with the rhythm of the film. “I like to think in overall terms,” he agrees. “I’ve talked to Kristen about this many times. What she feels is perfect operating is not necessarily the best thing for the scene. Sometimes she’ll say ‘I missed a bit of action because the framing was slightly off,’ but I often remind her that those sort of things can help the realism. Imperfection is not always undesirable. A film is like a dance and each shot has to fit with the rhythm.”

In the case of Star Trek VI, the limitations Narita had to contend with may in fact become the film’s strengths. The fact that its scale was limited means it had to focus on characters. “This film does have a strong story,” Narita agrees. “It just happens that the characters are Spock, Kirk and McCoy.” And Narita does feel he and Meyer succeeded to some degree in creating a much darker, moodier feel for this film than the others in the series. “We went for a harder edged look, and I would say I wish we’d done more,” Narita says. “We were fighting the tradition of Star Trek-type stories and trying to figure out how far we could push it. The Rocketeer was a much more comfortable film because we were approaching it with the idea that we didn’t know anything about it; there was no history to be concerned with and we knew we wouldn’t offend anybody. Here I wasn’t sure how much we could get away with. After all, all the actors have done this for 25 years. The director worked on the second one and helped write the fourth one. I didn’t want to see the film go completely dark and moody just for the sake of change — there were definitely some moments that shouldn’t be that way. I had a very good time working with Nick Meyer, even though he was pushing me quite a bit.”