Star Trek 50 Part XI — The Trek Feature Reboot

With Star Trek, cinematographer Dan Mindel, ASC and director J.J. Abrams update Gene Roddenberry’s universe for a new generation of fans.

This is the 11th entry in our 12-part retrospective series documenting 50 years of production and post on the Star Trek franchise. In this archival interview, Dan Mindel, ASC, J.J. Abrams and their team discuss how they brought na new creative vision to the venerable film series.

A Bold, New Enterprise

With Star Trek, cinematographer Dan Mindel, ASC and director J.J. Abrams update Gene Roddenberry’s universe for a new generation of fans.

Unit photography by Zade Rosenthal, SMPSP

In 1966, when audiences were introduced to Capt. James T. Kirk, he was already exploring strange new worlds, seeking out new life and new civilizations, and boldly going (with his equally enterprising crew) where no one had gone before. However, Kirk’s journey to the bridge of the USS Enterprise and his first contact with his core crew is a story that the Star Trek franchise’s six series and 10 feature films never told. Director J.J. Abrams has filled in the gaps with a new Star Trek feature that reboots the franchise, and he concedes that finding a look for the movie, which was shot by Dan Mindel, ASC, was a challenge. “This isn’t a reinvention to a degree that ignores the history of the franchise,” says Abrams. “We needed to embrace what had come before, but the spirit of what Gene Roddenberry created needed to be treated in a modern context, with an awareness of today’s audiences.”

Mindel, who previously teamed with Abrams on Mission: Impossible III (AC May ’06), recalls, “J.J. told us early on to use the original TV show as our key reference. He wanted us to pay attention to that young, go-get-’em, positive attitude.” Other Mission: Impossible collaborators who signed onto Star Trek included production designer Scott Chambliss and visual-effects supervisor/2nd-unit director Roger Guyett.

Mindel was eager to employ the anamorphic format for Trek’s 23rd-century vistas. “I’m not interested in using Super 35,” says the cinematographer. “J.J. wanted me to convince him to shoot anamorphic, so he and I looked at every test we could do, and when he saw the 50mm Primo projected, with the falloff in focus, he was convinced.” Guyett notes that although the distortion inherent in anamorphic lenses complicated the visual-effects work, “the result is worth it.”

The Trek crew’s first assignment took them aboard the USS Kelvin to shoot the opening sequence, in which the Kelvin is pitted against the time-traveling Romulan warlord Nero (Eric Bana) and his starship, the Narada. Chambliss says his design for the Kelvin, which predates the Enterprise by some 25 years in story time, “had the feeling of combining Flash Gordon with a Corvette commercial from 1965, with a cigar lounge thrown in for the bridge. Because it’s the first spaceship we’re on in the movie, J.J. and I wanted to do a bit of a fake-out that would enable us to make the Enterprise feel really different.” The Kelvin’s interior lighting is dominated by harsh toplight that was created with open, undiffused sources, and Mindel notes that “the Kelvin was where we learned everything we needed to know about lighting the Enterprise, but we had a lot more freedom on the Kelvin because there were places to hide lights.”

The hard-light strategy was carried into a power plant in Long Beach, Calif., that served as the Kelvin’s lower decks and engineering section. Chambliss describes the location as “stressed, textural and oily, which was the feeling we wanted the Kelvin to have.”

Mindel was intrigued by Abrams’ desire to shoot Star Trek on location as much as possible. The director explains, “This movie is a space adventure and could potentially feel artificial because of that premise, and I was very nervous about it not having guts and reality. I decided it would be critical to shoot in real, practical locations or build sets that would, for the most part, give us the freedom to shoot as if we were on a real location, perhaps with some set extensions.”

The introduction of the adult James Kirk (Chris Pine) takes place in an Iowa bar populated by Starfleet cadets. To create the futuristic watering hole, an array of 23rd-century adornments was added to the bar at the American Legion Hollywood Post 43. “We used some Blondes for toplight and a High End Systems DL.2 behind the door to project a moving image and add some life,” says gaffer Chris Prampin. “We also used Element Labs’ Stealth Displays and Versa Tubes, which are big, connectable LED pieces that allow you to put any color into them or run an image across them. We built [a rig with those units] big enough to encompass an entire wall, and, with the help of PRG, where we rented them, we had a full library of images and colors.”

During his momentous night at the bar, Kirk meets Nyota Uhura (Zoe Saldana), dukes it out with four of Starfleet’s finest, and endures a blunt scolding by Capt. Christopher Pike (Bruce Greenwood). Suitably chastened, Kirk musters the dignity to enlist in Starfleet and attend the Academy, where he befriends Leonard “Bones” McCoy (Karl Urban) and sows the seeds of his rivalry — and eventual friendship — with the half human/half Vulcan Spock (Zachary Quinto).

Later, when Spock’s home planet of Vulcan is threatened, Kirk and his graduating class receive their first field assignment, reporting for duty via shuttlecraft that take off from a large hangar. For the shuttle launchings, the filmmakers shot inside the Marine Corps Air Station in Tustin, Calif. A mixture of 16' HMI balloons and stand-mounted Gaffairs (rented from Skylight Balloon Lighting) provided ambience inside the 1,000'-long-by-300'-wide hangar, while 120' Condors rigged with Xenons and 18Ks on Arri MaxMovers swept the floor for added effect.

Shooting inside the shuttlecraft, Mindel would squeeze in a Kino Flo or LED panel for fill, and his crew would often position a Xenon angled in through the windows and bounced off a piece of Rosco Soft Silver on the floor. “It was really hard to get dollies in there, so we often shot handheld,” says Mindel. “That allowed the camera to be part of what’s going on.” (On larger sets, the filmmakers more often moved the cameras via a Steadicam or Technocrane.)

Boarding one of the shuttlecraft, Kirk and McCoy depart for the Enterprise and catch their first glimpse of the ship in space. “There are certain things you can’t let go of if you’re going to do Star Trek, and one of them is the general look and shape of the Enterprise,” says Abrams. “You want people to glance at it and go, ‘Yeah, it’s the Enterprise.’ And those who already know it can study it and realize how different it is.”

In updating Starfleet’s flagship, Chambliss abandoned the Kelvin’s pulp influences in favor of “designers who were interested in futurism and future technology, such as Eero Saarinen. I got some line drawings of the original exterior of the Enterprise, which was all right angles and flat discs, and started applying the curvature of Saarinen’s architecture to the main structural elements. It was an elegant approach that allowed the ship to be itself and get kind of sexy in the process.” To carry that sex appeal through the starship’s interior, Mindel tried to lend the sets “the feeling of a brand-new car, when it’s all sparkly. I sometimes used Tiffen Black Pro-Mists to give them a bit more sparkle, and I was very keen to have reflections on the set from glass, shiny objects and surfaces. It just feels so full of life when you get that.

“We made a huge effort to stay within the confines of the set and maintain the realism,” he continues. “We don’t like to fly out walls, and we built a vast amount of practical light into the set.” In the corridors, Mindel’s crew hung 2K Blondes and 750-watt Lekos above holes that the art department cut into the ceiling. “We also had MoleBeam Projectors in various parts of the hallway,” adds Prampin. “Al DeMayo, our lighting-fixtures foreman, made sure what we wanted was possible.”

Much of the lighting built into the interior was designed to cause lens flares, which serve as a visual motif throughout the picture. “The Enterprise has lights set in frame that basically point down the lens of the camera in every direction,” says Mindel. “Wherever you look, you get a flare. It goes against everything one learns as a camera technician, which is to shield the lens from any extraneous light and stop it from flaring. We’ll either get slaughtered by our peers or be really admired for it!” Abrams adds, “The flares often weren’t made by a light source in the frame, and to me, that implies there’s something extraordinary happening just off camera. It makes me feel like I’m not watching the average moment. And I love the idea of a motif that is so inherently analog and imperfect in its unpredictability; it serves as counterpoint to the sterile, controlled look that so many visual-effects films seem to have.”

If the built-in lighting wasn’t providing the desired flare, the crew aimed Xenon flashlights at the lenses as the cameras rolled. “Our A- and B-camera operators, Colin Anderson and Phil Carr-Forster, would tell us if we needed to go a little farther in or out of the frame, or up or down, to get the ultimate flare,” recalls Prampin. “It was funny to watch — Dan and I were running around, ducking, jumping and hiding behind things just so we wouldn’t be seen by the cameras. The flashlights were so bright that there are probably several instances where Dan’s actually in the movie, but you can’t really tell!”

On the Enterprise’s oval-shaped bridge, the primary flare inducers comprised a ring of MR 16s and MR 11s fitted into the wall; each was mounted so it could be slightly panned and tilted for maximum effect. “The bridge had many lighting opportunities built into it: screens, buttons, blinking lights and all the bells and whistles,” notes Chambliss. “It feels contemporary and utterly fleshed out.” The consoles manned by Spock, Hikaru Sulu (John Cho) and Pavel Chekov (Anton Yelchin) featured practical fixtures from the art department and built-in LiteGear XFlo dimmable fluorescent fixtures, which were also installed beneath milk-glass floor panels under the set’s centerpiece, the captain’s chair. The XFlos, run off a dimmer-board system programmed by Joshua Thatcher, “allowed us to put a little life into [the set],” says Prampin. “We could set up a little pulse in them, or we could make it look like something was flickering and the power was going out.”

Red-alert situations have been a Star Trek staple from the very beginning. To make the most of those sequences, Mindel had the electricians fit a red-gelled XFlo alongside all of the clean tubes built into the bridge, enabling the dimmer-board operator to instantaneously establish the red-alert look. To further punctuate the change in ship’s status, “we incorporated a lot of LED technology, such as LiteGear LiteRibbon RGB strips, which allowed us to change the color,” says Prampin. The strips were installed as architectural accents around steps and other cutaways on the bridge; when not in red alert, the strips glowed blue to match Neoflex tubing running through narrow channels Chambliss designed into the set’s walls and ceiling. (Neoflex is a flexible, plastic-encased LED strip that creates a glow similar to a neon fixture.)

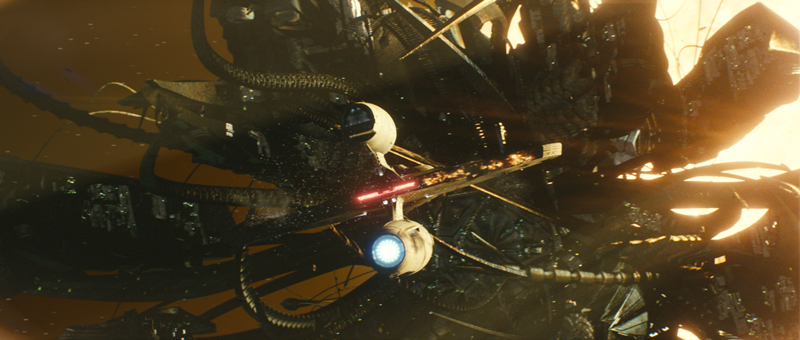

When the Enterprise arrives at Vulcan, its crew finds the planet endangered by Nero’s Narada, which, Chambliss says, “makes the scale of the Enterprise look rather insignificant.” To economically suggest the immense scale of the Narada’s interior, Chambliss drew on his experience working in theater. “I thought we should treat the soundstage like a theater stage and create a world where we could mix and match elements to create different and new environments over and over again. It’s not a traditional way of designing movies, but it’s a very traditional way of designing theatrical scenery.”

Last year, AC visited the Paramount soundstage housing the Narada’s interior “elements.” The result of Chambliss’ approach was a seemingly random arrangement of almost countless pieces, some on casters, some incorporating display interfaces and Romulan insignia, some hanging from wires run to the ceiling, and many featuring corrugated black tubing that lent the entire stage an eerie quality that was enhanced by Mindel’s use of smoke and yellow light. “The larger tower elements could be shot from any side,” notes Chambliss. “We could put them together to make some massive structure, or we could pull them apart, flip them sideways and fly them up in the air. Much to my delight, as soon as I showed J.J. a model of this approach, he instantly got it and started going along for the ride. He told me it felt like having a stage full of toys.”

“Given that the set was going to change on the fly, we had to be able to change the lighting on the fly,” says Mindel. “We built in the ability to control our lights from a dimmer board and rearrange what we were doing remotely.” Accordingly, the cinematographer employed a number of moving fixtures — including Vari-Lite VL3500s and Clay Paky Alpha Spot 1200s — above the set, with Nine-light Maxi-Brutes, MoleBeam Projectors, 5Ks and 10Ks cutting additional shafts through the smoked interior. On the floor, Kino Flos gelled with Lee 101 Yellow were placed to light particular set pieces, and the outer edge of the set was lined with a painted backdrop that was alternately frontlit with Far Cycs or backlit with Sky Pans. “It was a pretty abstract backing, so we tried to be abstract with our lighting and just pick spots that worked with the set’s configuration at the time,” says Prampin.

During AC’s visit, a phaser battle was staged inside the Romulan ship. Between takes, prop master Russell Bobbitt offered a close look at Starfleet’s standard-issue sidearm. Staying true to the phaser wielded by the series’ original cast members, the updated firearm still boasts both “stun” and “kill” settings; now, however, the two settings are visually differentiated with the press of a thumb switch that physically flips the barrel 180 degrees. “With the guns, gadgets and all of the control panels, our intention was always to provide a literal functionality,” says Chambliss, who praises Bobbitt and set decorator Karen Manthey for their “enormous and carefully considered contributions” to that work.

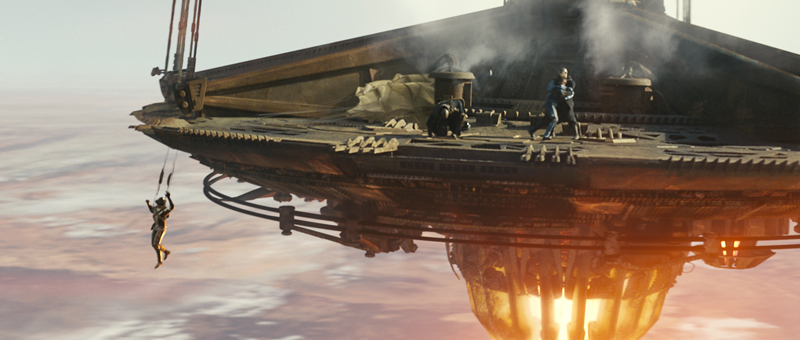

Before traveling back in time to wreak havoc, the Narada was a mining vessel, and Nero now uses its retractable drilling platform as a devastating weapon. In an attempt to render the weapon inoperative, Kirk, Sulu and a “red shirt” named Olsen (Greg Ellis) space-dive out of a shuttlecraft and into Vulcan’s atmosphere, landing on the platform. A wedge of the platform was constructed in Dodger Stadium’s parking lot and backed by greenscreen; the site’s elevation allowed Mindel to shoot into the sky without fear of glimpsing the Los Angeles skyline. “We learned on Mission: Impossible that these big greenscreen sets work better outside,” says Mindel. “You get the ambient dust and wind and sunlight, which really help sell the gag.” Condors also stood at the ready with Nine-light Maxi-Brutes and Dinos for backlight and 100K and 50K SoftSuns for fill.

The approach “certainly didn’t make compositing the sequence easy,” says Guyett. “With a really gnarly set, greenscreens get dirty and become less effective, but I think if we’d done it [onstage], there would be a greater chance of people looking at it and saying, ‘I don’t really believe they’re outside.’” Mindel adds, “Part of working on this kind of movie is learning about the [visual-effects] technology, and Roger’s very keen to teach guys like me. He and I shared the experience all the way to the digital intermediate, because the biggest issue is blending everything together seamlessly [in post].”

The filmmakers carried out the DI at Company 3 with colorist Stefan Sonnenfeld. “Shooting on film, which is really important to me and Dan, and then doing the DI with Stefan allowed us to do a critical and final pass that was in some cases about color-correction and in other cases about being incredibly creative and giving certain locations an even bolder look,” says Abrams. Mindel notes, “Kodak offered us [Vision3 500T] 5219 because of its greater latitude, but I found it lacked the initial contrast that I like; I’d much rather have the contrast on the negative than try to add it afterwards.” He opted instead to shoot two Kodak Vision2 negatives, 100T 5212 (day exteriors) and 500T 5218 (interiors). “We shot at T2.82⁄3 basically all the time, and I like to use zooms on set, so I pushed by half a stop to give us enough light when we were inside or shooting at night,” adds Mindel.

After the mission is accomplished on the drill platform, Sulu is jolted off and into freefall. When Kirk jumps after him, it falls to Chekov, aboard the Enterprise, to lock onto the plummeting targets and beam them back to the transporter room. In the transporter-room set, “we had some floor and ceiling lighting effects that remained fairly similar to the look of the original series,” says Mindel. Prampin adds, “We gave the art department old Fresnel lenses out of 10Ks, and they actually incorporated those into the set for the characters to stand on.” A mix of 10Ks and Nine-lights provided illumination from below the transporter, and 2K MoleBeam Projectors were aimed through holes designed into the ceiling. The transporter remained dark “until the characters stood on it, and then we would gradually start putting a little light into it,” says Prampin. “Eventually, we would get to an overexposed state, at which point the characters would ‘disappear.’” (25K SoftSuns and 8K Paparazzis enhanced the effect.)

When Pike falls into Nero’s hands, Spock becomes acting captain of the Enterprise, and in the interest of logic and efficiency, he decides to keep Kirk out of his way by jettisoning him to the ice planet Delta Vega. The planet’s exterior was constructed alongside the drill platform at Dodger Stadium. “We mocked up a proof-of-concept on the computer and did a very quick survey of the car park,” says Guyett. “We ran a Sunpath on the two sets, and we were able to present this concept of shooting the two sets side-by-side and demonstrate that it could actually work. J.J. would do first unit on one, I’d do second unit on the other, and then we’d swap.”

Cinematographer Bruce McCleery, a longtime collaborator of Mindel’s, shot the second-unit material. The filmmakers combined several techniques to suggest a larger space than conventional construction could provide in the stadium’s parking lot. “We shot plates in Alaska, and we did a lot of fantastic DigiMatte work to create the ice environment,” recalls Guyett. (Aerial director of photography David B. Nowell, ASC shot plates in Alaska and Utah.) A bluescreen, illuminated by 18Ks, wrapped around the Delta Vega exterior, and above the set, key rigging grip Rick Rader suspended a large silk from a construction crane that could be moved depending on the position of the sun. For additional fill, Mindel used 100K and 50K SoftSuns.

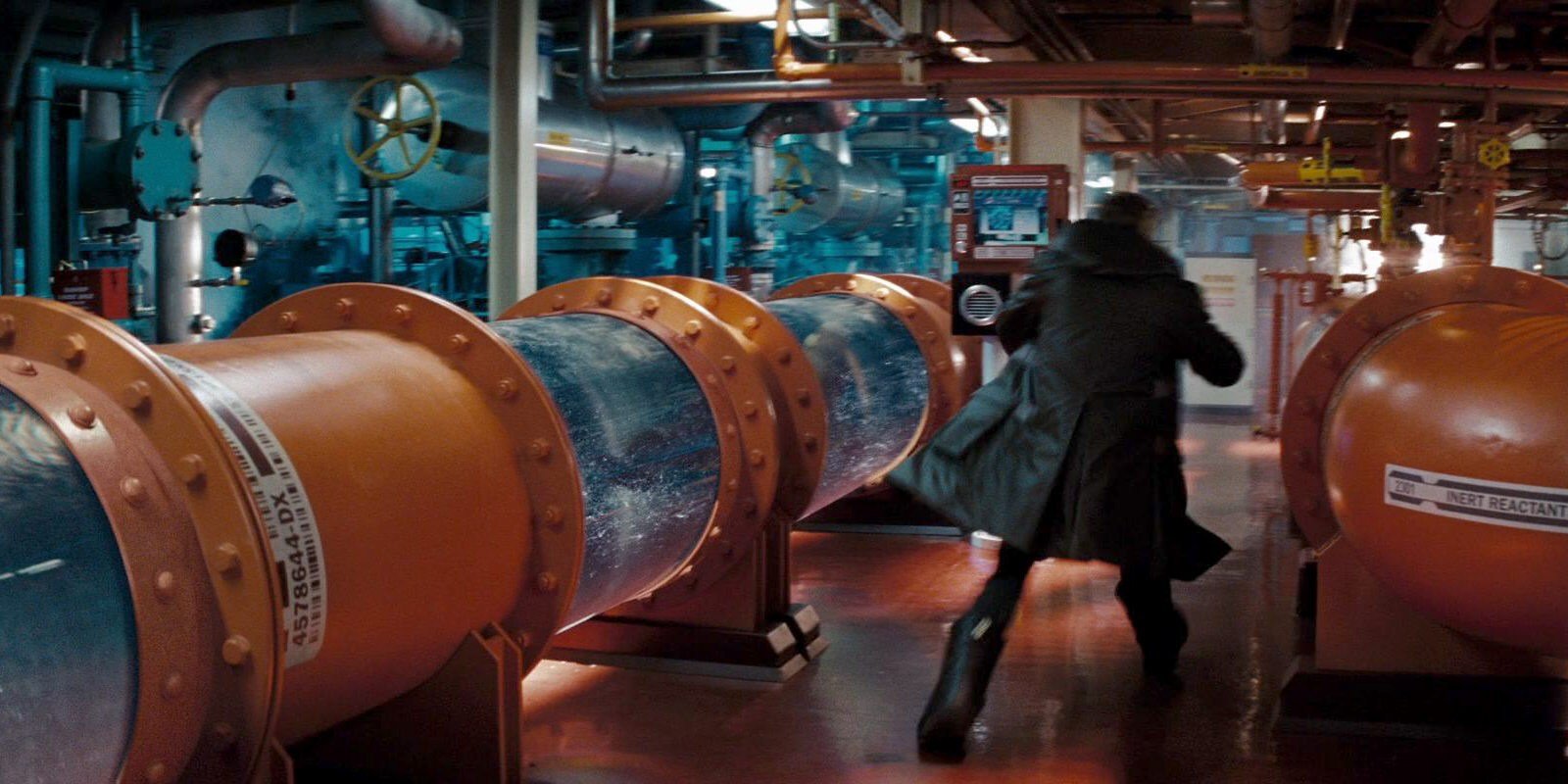

Seemingly stranded on the ice planet, Kirk encounters an elderly Spock (Leonard Nimoy), who has traveled back in time in pursuit of Nero. This Spock leads Kirk to a Starfleet outpost tended by Montgomery Scott (Simon Pegg). The outpost set was built in a part of the Anheuser-Busch brewery in Van Nuys, Calif. “We used Par 64 space lights to create little pools of light for people to walk through, but for the most part, we kept it pretty subdued,” says Prampin. “To hide the back wall, Scott Chambliss put up a bunch of chain-link fence with some aged plastic on it, and behind that we stuck a lot of 4-by-4 Kinos, some gelled with Lee 179 Chrome Orange and some with Lee 219 Fluorescent Green. We also used some Kinos in and around Scotty’s station, but we mostly keyed that with Blondes through diffusion, usually Lee 129 [Heavy Frost].”

After the elder Spock shares a future formula of Scott’s with the young engineer, Scott and Kirk manage to beam back to the Enterprise as the ship travels at warp speed; Scott’s calculations, however, land the pair in the engineering decks. For this scene, the filmmakers sought a large-scale location “that would feel clean and fresh instead of oily and disgusting,” says Chambliss. “Instantly, we thought of major food-processing plants, and our research led us to the [Anheuser-Busch] plant.” Mindel explains, “We shot in a pump house, which was so noisy that everyone had to wear ear protection. We also shot in the fermentation house, which was refrigerated — it was 100°F outside, and we were all inside in protective clothing! The fermentation tanks gave us many reflections and great-looking pings off the stainless steel, but we had to be very careful about what kind of lights we used, where we used them and for how long, because you can’t change the temperature of the ambient air very much before you mess up all the beer.

“We only used fluorescents to key with, and we were able to light backgrounds with conventional lights and turn them off between takes so they never got too hot,” he continues. “We weren’t allowed to bring dollies up there, so we shot with the Steadicam.” The filmmakers also tapped some of the location’s existing mercury-vapor worklights. “We just wrapped them in a little Rosco Scrim to control their level and brought in our own lights to augment that,” says Prampin.

With Kirk, Spock, Bones, Scotty, Uhura, Sulu and Chekov all finally aboard, the Enterprise boldly enters danger’s maw to conclude its first adventure. Proud to have enlisted for another voyage with Abrams, Mindel reflects, “J.J. enjoys what he does immensely, and he wants us all to bring our best and show him something a little different from what’s been seen before. His mantras are that the work should be fun, and you should respect the audience. We tried really hard to make this film worthy of its name.”

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS

2.40:1

Anamorphic 35mm

Kodak Vision2 11T 5212, Kodak Vision2 500T 5218

Panaflex Millenium XL, Platinum, PanArri 435

Panavision Primo

Digital Intermediate

Printed on Kodak Vision 2383

This article originally appeared in American Cinematographer, June, 2009. It retains the original text and style as it was originally published.