Star Wars Rebels: Animated Allies

CG lighting and effects supervisor Joel Aron and his collaborators detail their approach to the hit animated series' cinematic visuals.

All images courtesy of Lucasfilm Ltd.

This story originally appeared in AC February 2016.

On a Friday at the end of July, AC visits Lucasfilm’s campus at the Letterman Digital Arts Center in San Francisco's Presidio. The entrance to Building B is just past the Yoda fountain. Tracy Cannobbio, Lucasfilm’s senior manager of animation and franchise publicity, enters the building’s lobby — which is adorned with memorabilia big and small celebrating all things Star Wars — from the hallway opposite an imposing, life-size replica of Darth Vader, and then leads the way to an unoccupied suite with a view of the bay.

A moment later, Joel Aron hurries into the room with a Leica M digital camera slung over his shoulder and a MacBook Pro laptop under his arm. This marks a rare occasion when he’s fitted his Leica with a 21mm lens; as he explains, “I walk around with a 50 on my camera religiously.” Aron is the CG lighting and effects supervisor on the Disney XD animated series Star Wars Rebels — as well as an avid stills photographer, evidenced by his ever-ready camera — and he’s about to carve two hours for this interview out of a day in which he still needs to view lighting dailies, prepare a lens guide for this coming Monday’s layout kickoff, sign off on what is hopefully an episode’s final retake, give one last look to another episode’s color grading, and eat lunch. “It’s a Friday,” he says, as though without a care in the world. “Overseas studios are asleep.”

Rebels takes place some five years before the events of Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope, and follows the crew of the Ghost, a customized freighter captained by ace pilot Hera Syndulla (voiced by Vanessa Marshall). Joining Hera in guerrilla strikes against the Galactic Empire are Kanan Jarrus (Freddie Prinze Jr.), a Jedi Knight in hiding; Sabine Wren (Tiya Sircar), a munitions expert with a penchant for artistic expression; Garazeb “Zeb” Orrelios (Steve Blum), whose oft-needed muscle belies a genuine soft side; Ezra Bridger (Taylor Gray), a Force-sensitive teenager; and the snarky astromech droid C1-10P, better known as “Chopper.”

The first season of Rebels followed the characters as they gave the Imperial presence on the Outer Rim planet Lothal enough grief to garner the unwanted attention of Grand Moff Tarkin (Stephen Stanton) and Darth Vader (as in the films, voiced by James Earl Jones). In season two, the Ghost crew has traveled farther afield and joined up with Phoenix Squadron, part of the burgeoning Rebel Alliance. (At press time, Rebels had just been renewed for a third season.)

Rebels was among the first new Star Wars content released under the Disney banner after the company’s blockbuster purchase of Lucasfilm in 2012. To get the show to air in a timely fashion, its development was decidedly short; as a result, its workflow bears a striking resemblance to the one that had been refined over seven seasons of the animated series Star Wars: The Clone Wars. Smoothing the transition between the two shows, Rebels has reunited much of the Clone Wars production team, including Aron, lighting concept artist Christopher Voy, colorist Sean Wells, and executive producer and supervising director Dave Filoni, each of whom spoke with AC in separate interviews.

Aron was a 17-year veteran of Industrial Light & Magic when, in late 2007, he was tapped to go overseas and help the Lucasfilm Animation Singapore team learn some tricks with Maya to help speed their output on the nascent Clone Wars animated series. Shortly after his return stateside, he was asked to join the show as an effects advisor, beginning with the first-season episode “Trespass.”

Aron’s role would quickly grow to encompass both effects and lighting, and he credits Don McAlpine, ASC, ACS for preparing him for the latter. The two had worked together when Aron was on set in Australia, working as the visual-effects match-move supervisor on Peter Pan (AC Jan. ’04), which McAlpine shot for director P.J. Hogan. “For that whole year,” Aron says, “I just picked his brain.”

As he segued from The Clone Wars to Rebels, Aron’s first order of business was to immerse himself in A New Hope so that he would be able to infuse the new series with a similar style. To complement his repeated viewings of that film, he visited the Lucasfilm archives at Skywalker Ranch and, with the help of the archive staff, pored over the original continuity sheets. Together, they compiled a document that lists the lens used for every single setup in the film. For Rebels, Aron says, “I stick with the same theories based on what George [Lucas] and Gil [Taylor, BSC] did on Episode IV.”

Aron works with simulated VistaVision optics — the default in Autodesk’s Maya, which is used for the majority of the workflow, including model construction and lighting. “We render with [Maya plug-in] Mental Ray,” he adds, “and we use [The Foundry’s] Nuke for compositing. We try to keep the software list low, because it allows us to be agile.”

Even more so than A New Hope, the overarching inspiration for the look of Rebels is the concept art Ralph McQuarrie produced for the original Star Wars trilogy. “The real task became, ‘How are we going to translate [McQuarrie’s style]?’” Filoni says. “Joel worked closely with Kilian Plunkett, my art director and lead designer, as far as texture and surfacing goes [and] how much reflection we would need. Something Kilian and I gravitated toward was Ralph’s line work — he did a lot of pencil lines on his paintings. So instead of a lot of geometry in our CG models, we incorporate a lot of surface-drawn lines, which give a nice hand-rendered feel and the [illusion] of detail, which works well for our pipeline and rendering ability.”

Alongside this technique, the production also employs a custom shader, which is applied as a surface material to the characters. As Aron explains, “The shader used for the skin is a three-tone shader, like a ‘toon shader.’ When you apply contrast to it in color correct, it flattens, which is exactly what we want — like a [Hayao] Miyazaki or Ralph McQuarrie image.”

Another aspect of the McQuarrie style is deep focus, which comes naturally to animation, as the CG lenses aren’t beholden to the rules of real-world optics and their depth-of-field characteristics. However, Aron keeps a few tricks up his sleeve for specific shots that might otherwise call for an out-of-focus background. For example, he explains, “If we’re up [close] on Ezra and he’s using the Force, I like to drop the background brightness to take interest off the background and subtly simulate depth of field. And whenever I use a lens above the 100mm, I’ll ever so subtly add a circle blur [to the background], which simulates circles of confusion.”

One of the most pronounced stylistic departures from The Clone Wars is the change in aspect ratio from 2.39:1 to 1.78:1. “I have to say, that was a downer,” Filoni opines. “We all miss [2.39:1]. It’s cinematic; there is no substitute for it. But, very simply, we made the change because it’s less to render. [With] 16:9, we can get things done a little faster.”

The narrower aspect ratio required the crew to rethink their approach to framing, and as Filoni notes, “there are considerations for characters.” For example, although the taller frame makes it easier to compose Darth Vader alongside his decidedly shorter castmates, “Joel and I learned very quickly that if you shoot Vader from a strange angle, he won’t look like the Darth Vader you remember,” Filoni continues. “If you shoot him from the side, you realize how big that helmet is and how narrow his body is — especially on our animation model. You have to be aware of all of that in your animated actor.”

Vader requires particular finesse when it comes to reflections, which The Clone Wars eschewed completely but Rebels incorporates sparingly. Years ago, Aron was on set for a series of Burger King commercials that featured the iconic Dark Lord of the Sith, and that real-world experience informed his approach to Rebels’ CG Vader. His solution, he says, is to light Vader “like a car commercial.” Working in Photoshop, Aron painted a cyclorama that he then took into Maya for lighting. “Wherever Darth Vader goes, he’s got that cyc,” Aron says. “Otherwise, he reflects the room and looks like a CG chrome ball.”

As the show’s CG character and spaceship models were finished and painted, Aron did a series of lens tests with each, seeing how it looked at various distances when “photographed” with various focal lengths. “The 50mm is always my go-to,” he says. “When I need to go wide, it’s usually the 35mm. I’ll usually use the 75mm on Sabine or Hera, but I won’t do the 75 on Kanan, because it narrows his head a little too much. Whenever Ezra starts to use the Force, I go 75mm on him. When you cut to the object he’s using the Force on, I match and go 75mm there, too. As soon as the Force is broken, I’ll go to a 50mm so you feel that little punch.

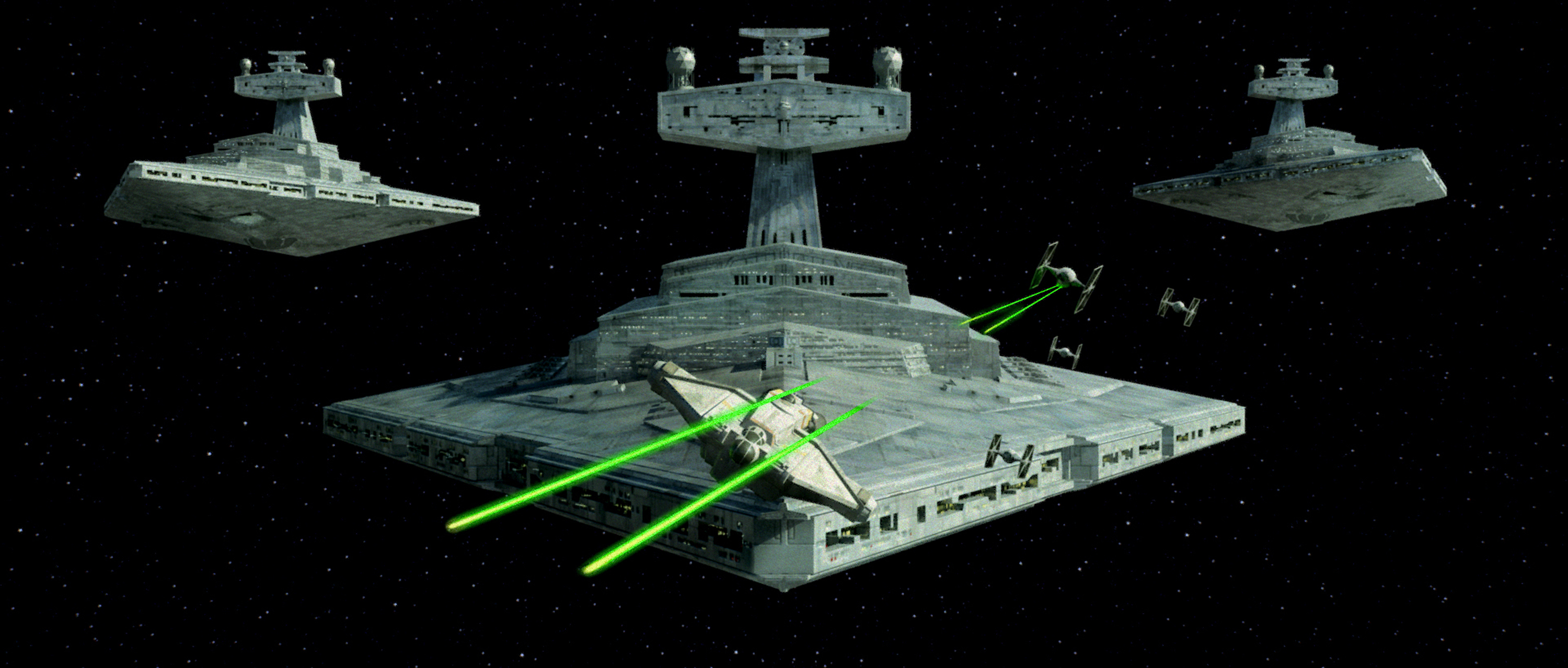

“Spaceships are always [shot with] a 50mm or 75mm, and that comes from talking to [ILM and original-trilogy veterans] Dennis Muren and Paul Huston,” Aron continues. “Whenever we see a Star Destroyer, I like to go even longer, like 100mm.”

For each episode of Rebels, the design team sets to work on any new assets the story will require — sometimes even before the script has been locked. Once approved, the designs go to digital-assets supervisor Paul Zinnes and his team to be rigged as CG models. Simultaneously, the storyboard artists begin working in close collaboration with Filoni and — unless Filoni is directing the episode himself — the episodic director.

The finished storyboards allow Aron to pick the lens for each shot. “If I have any questions about how [the shot is] drawn, I’ll open up the scene in Maya, throw lenses on it and see how it could work, whether I need to remove any geometry or float a wall to get the shot we need,” he explains.

When it comes to placing the virtual camera in the CG environment, A New Hope again serves as the crew’s guide. In that film, Filoni observes, “the camera never is in a place that you couldn’t really get it. A lot of the film is shot on sticks — it’s almost documentary-feeling. So I’m always on our episodic directors to say, ‘How can we get that feeling of watchfulness, so that it makes the world of our animation feel real?’”

As they had on The Clone Wars, the team at Lucasfilm is again collaborating with Taipei, Taiwan-based animation studio CGCG; season two of Rebels has seen the addition of Saigon, Vietnam-based studio Virtuos-Sparx. “CGCG does 17 of the 22 episodes in the season, with Sparx picking up the other five,” Aron explains. For each of its episode assignments, each studio assembles a layout, which translates the 2D storyboards into 3D shots, establishing the camera’s position and movement, confirming the blocking of all action within the frame, and generally ensuring that everything is in place for animation supervisor Keith Kellogg’s team to begin actually animating the episode.

“The biggest thing in animation is how to translate a 2D storyboard into a 3D world,” Aron stresses. “This is when we’ll talk about how the camera moves. There are things that may look good on boards but don’t translate well in 3D; we have several meetings about layout just to make sure it’s right.”

The storyboards also serve as the foundation for lighting-concept paintings, which Voy creates in order to set a template for the lighting design and color palette of key moments in each episode. Aron will typically select 15 or so such key frames from the storyboards, and then Voy will take those gray-scale storyboards into Photoshop and paint directly over them, incorporating assets from the design department and following notes about lighting and effects that came out of discussions with Filoni, Aron and others.

“The interplay of light and dark is the unconscious part of [the second] season,” Filoni notes. “Ezra’s struggling with becoming more powerful. When you become more powerful, there’s always the danger of seizing that power for yourself, even when you think you’re doing good for other people — Anakin went through that [in the prequel films]. So, especially in the Jedi-centric episodes, you’ll often see people standing at the edge of a shadow. That’s all very orchestrated.”

Voy, who joined the production of The Clone Wars at the same time as Aron, notes that the lighting concepts on Rebels are “pretty similar to what we did on Clone Wars, but with a shorter turnaround.” For each episode of Rebels, Voy has two weeks in which to make all of his lighting concepts and assist the overseas studios with the matte paintings that will be composited into the final animation. “I’ll try to get my first pass of everything finished in a week,” he explains, “and then use the next week to do any revisions we need.”

Asked how the crew decides what frames will get a lighting concept, Voy offers, “Joel will have an idea of what shots he wants to get a pass at because they might be especially difficult — if there’s a complex effect, or if we have a new set, we’ll try and get a painting. So he picks the ones that might [require] the most back and forth with the overseas studios, where having a painting can help hammer it out on our side so we can send it over and say, ‘Try and match this as closely as possible.’”

Before the lighting artists at CGCG and Virtuos-Sparx set to work lighting the raw animation, Aron leads the overseas team through a “lighting kickoff.” As Aron explains, “We go through every single shot and I explain how the characters should be lit, how bright the background should be, where the focus should be.

“I dwell more on the first time you see a character than anything,” he emphasizes. “The first time you see any character in any episode, I want it to look like a portrait. I don’t care what the light is on the set; I want a top-down 45-degree key [light] that matches the tone of the room.”

Eye lights are also one of Rebels’ stylistic tropes. “Our characters should always look like we put a tiny white Avery dot on their eyes,” Aron says. The lighting artists utilize a rig within Maya that allows the key light to easily drive where these specular highlights appear. “You’ll notice the iris color moving, as well,” Aron adds.

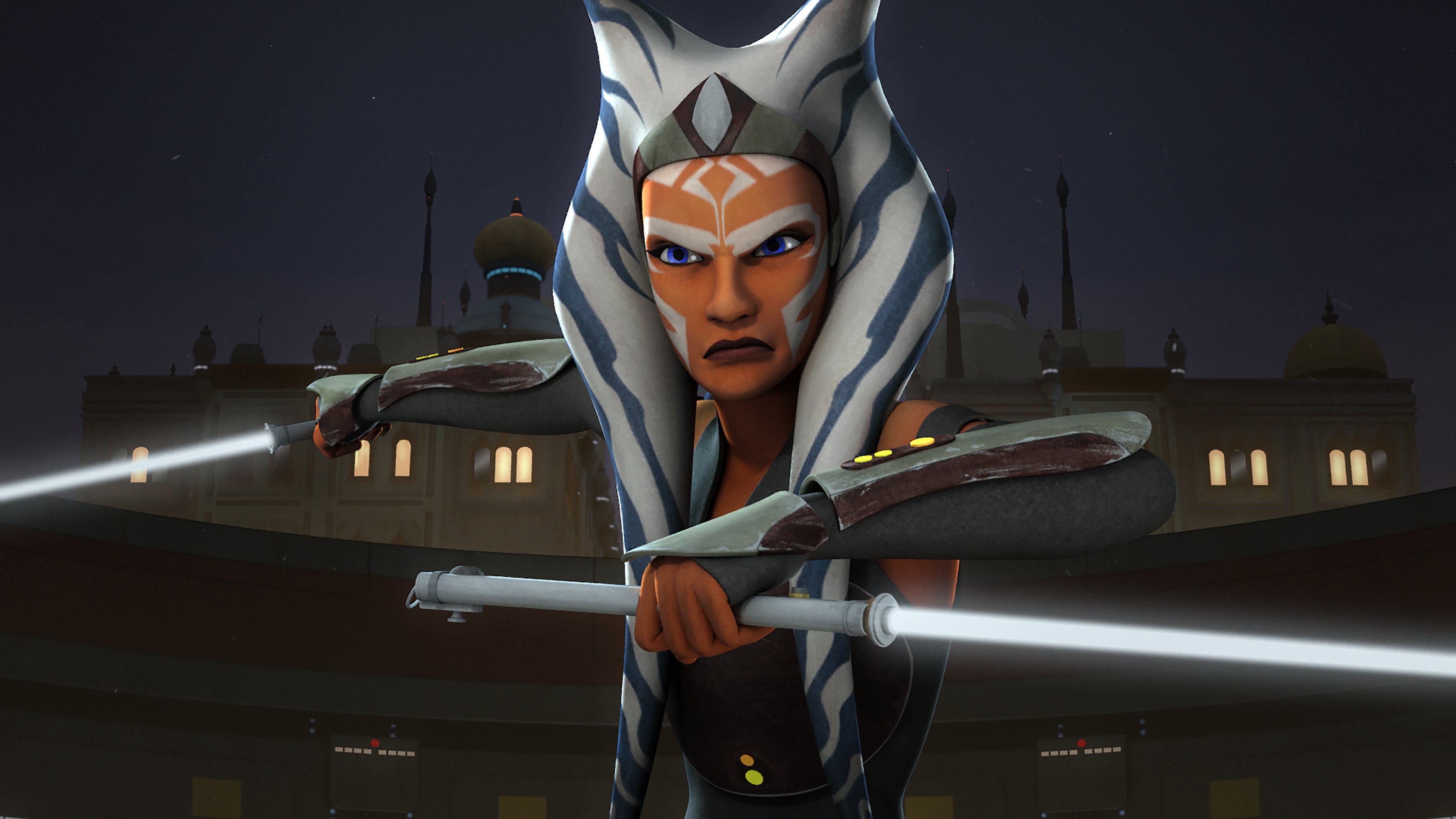

Rebels presents a particularly diverse array of skin tones, from the green-skinned Hera to the orange-skinned Ahsoka Tano (Ashley Eckstein), the erstwhile padawan of Anakin Skywalker and a key organizer of the early Rebellion. To accommodate that range, Aron says, “we usually try to keep the [key] lights as neutral as possible.” In communicating color temperature with the lighting artists, he avoids Kelvin numbers in favor of referencing Voy’s lighting concepts and examples from films. “What I’ve found on both Clone Wars and Rebels is that it’s best to get the shot in the ballpark, and then Sean and I will push it towards our final look in the grade,” Aron explains.

When it comes to lighting ships in space, “you always see the sun side,” Aron notes. “Whenever you saw the Millennium Falcon flying, it was always lit. We do the same thing with the Ghost.

“As soon as you get into a cockpit, it doesn’t matter [where the light is coming from],” he continues. “I just want to see the light moving.” Aron’s cockpit-interior lighting incorporates gobos that he makes in Photoshop for use in Maya. “I do that incessantly,” he offers.

The manner in which the CG lights are shaped and controlled requires a unique toolset as compared to live action. Aron explains that he manipulates controls within Mental Ray so that, for example, “if I’ve got a spotlight, I can make that spotlight have a quadratic falloff, a linear falloff or no decay. So the light can beam like a laser, or it can fall off like it’s being shot through a grid or another diffuser.”

To communicate the desired levels of brightness in any given frame, Aron predominantly relies on light ratios. “I target 2:1 or 3:1 when giving notes,” he explains. By taking this approach, he adds, “I can focus more on the actual lighting composition of the shot and not worry too much about exact stops, knowing that I will be working with Sean in the final grade to push contrast back into the images.”

As the lighting starts to come in from the studio, Aron, Voy and others will review the work in a lighting-dailies session. Aron offers his feedback to the studio in the form of notes and paint-overs. For the latter, he uses Photoshop and a Wacom Cintiq display to paint the desired changes directly over the submitted frame. The artists on both sides of the Pacific utilize Tweak Software’s RV playback and review application, which allows the lighting artists to compare their submitted shots with Aron’s paint-overs. “I only have about 5 or 10 minutes for each paint-over,” Aron explains. “I usually do 10 a week, and it sometimes goes up to about 20 or 30.”

Concurrent with the lighting, Aron shepherds the series’ effects, including atmospherics such as smoke, haze and clouds, which “can get very expensive,” he says. To cut down on those costs, he adds, “we go right back to the 2D method. We can’t let the computer do everything!”

As an example, he points to the season two-episode “Relics of the Old Republic,” in which our heroes — who have allied with aging clones Rex, Wolffe and Gregor (all voiced by Dee Bradley Baker) — are pursued through a blinding dust storm by a trio of hulking Imperial walkers. He explains, “I taped my iPhone to my tripod; I poked holes in a cup; I grabbed salt, sugar and Splenda, and put it in the cup; I took two desk lamps; and then I shot slow motion.” The iPhone captured the “dust” — backlit by the desk lamps and shot against a black backing — as it fell through the holes in the cup. “Once CGCG was done with most of their dust stuff,” he adds, “I took this element, turned it sideways and laid it over the top [of the animation]. And it works really, really well.”

One of the first effects Aron had to crack for Rebels was the look of the show’s lightsabers. Here again, his close analysis of A New Hope paid dividends. For that film, the lightsaber hilts were connected to spinning dowels covered in a reflective tape that would appear to glow, from the camera’s perspective. Although rotoscoping would ultimately carry the effect across the finish line, the movement of the spinning dowel is still evident — for example, in the medium shot of Obi-Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness) after he quite literally disarms the threatening Ponda Baba in the Mos Eisley cantina. Aron worked out the cycle at which Kenobi’s saber blade spun and flicked back and forth in this scene, and that cycle was then re-created in Maya, where it is applied to all of the lightsabers seen in Rebels.

“Joel is my wizard,” Filoni enthuses. “How he manages to get so many shots done so beautifully is still mind-blowing to me. It spoils you as a director; you just want to keep coming up with more challenging environments. But that’s Joel’s character — he doesn’t want to say ‘no.’ He’s one of those guys from the old school of ILM [who believe] that the best kind of problem is the one that we don’t have a solution for, so they come up with it.”

Making a season’s worth of 22-minute episodes is far from a linear, prep-through-post experience for the Rebels team, as multiple episodes are in various stages of production at any given moment. “If I were to run my finger down the schedule on today’s date,” Aron explains, “I would cross over 14 episodes that are in progress in one state or another. We have nine weeks for lighting and effects per episode; it works out that four episodes are in the lighting and effects phase in the schedule at once. Add in to that the four prior episodes that are in the retake phase — cleaning up or adding shots to the final edit based on notes from Filoni or Disney — and on a good day, I’m reviewing shots from eight episodes.”

Once the last retake is in hand, Aron can sit down with Wells to begin the color correction. Wells works on site at Lucasfilm, where he uses Digital Vision’s Nucoda to grade the production’s native 16-bit EXR files and deliver a 1920x1080 10-bit DPX for mastering and the creation of all of Rebels’ requisite deliverables, including files for broadcast, download and Blu-ray. While grading, Wells alternately references a Christie CP2215 projector, a Flanders Scientific AM420 monitor and a Panasonic ZT60 65" plasma television.

Wells is typically given five days to grade an episode. “It’s a little more than live action would be,” he says, “but we do a lot more compositing-style adjustments in the system to [further] sweeten it as we go.”

After working in visual effects at The Orphanage, Wells joined the production of The Clone Wars at the beginning of the second season, starting with the episode “Hidden Enemy.” He graded every subsequent episode through the series’ conclusion, and has been with Rebels from the start. In the time they’ve spent working together, Aron says, “we came up with a shorthand for what we need to do. I’ll give him notes like, ‘Slam left, swell bottom,’ so Sean can just fly.”

Asked what it means to “swell” an image, Wells laughs and explains, “People call me ‘Swells,’ so Joel took that. It’s basically a heavy vignette; usually we throw it on the top and bottom of the screen to help pull the center out. It’s not like we invented an optical technique; it’s just when he says it, I know the shape, the feathering and the aggressiveness of the vignette.”

The Nucoda is also used to add simulated film grain to the animated image, which works in concert with edge dithering that’s applied during rendering to break up high-contrast edges. “Usually in CG, you’ll have these crisp edges, but if you edge-dither all the high-contrast lines and then put grain on top of [the image] in post, you get this film look,” Aron explains.

Wells adds, “Joel’s instinct is to not keep everything ‘CG perfect,’ where you know it came from a computer. We also do a lot of highlight blooming and other things to soften and gnarl up the image a little bit before it goes out, so it has a ‘feel.’”

With his dailies session looming — after he’s already postponed it once so as to not have to cut short this interview — Aron racks focus to his collaborators. “I can’t speak enough about the team that I work with,” he stresses. “There’s no individual who really pushes this show in any direction — other than Filoni, and even then he’ll say that we couldn’t do what we do without being that team.”

In turn, Filoni offers, “I think Joel and Chris and Sean would all agree that we were very fortunate to have George Lucas himself instruct us along the way. He always used to tell me that he spent so much time working with us so that one day we could do it without him — and I always thought he was joking, and then that day came. But my team and I embraced the opportunity. I mean, it’s the proper apprentice path, right? You eventually have to take these steps on your own, and I think we’ve taken them well.”