Straight Shooting on The Straight Story

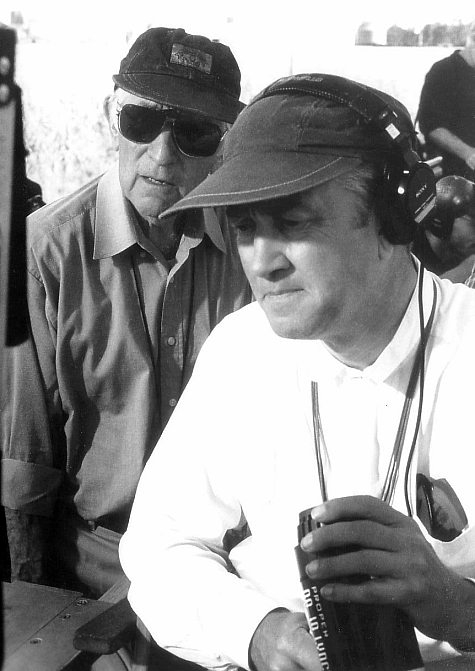

With this road-trip picture, Freddie Francis, BSC and David Lynch deliver a unique portrait of a man driven by his independent spirit.

In 1994, Alvin Straight, a real-life resident of Laurens, Iowa, heard that his estranged brother had suffered a stroke. Formerly the best of friends, the two had quarreled acrimoniously and not spoken for a decade. Straight, over 70, in poor shape and recovering from a bad fall, was determined to reconcile with his sibling, who lived some 300 miles away in Mount Zion, Wisconsin. Unable to drive a car due to his poor eyesight, and too proud to be driven, Straight made his painstaking pilgrimage aboard a slow-moving riding lawnmower while towing a makeshift trailer. His successful journey took several weeks and was not without incident.

This slice of Americana caught the imagination of producer/writer/editor Mary Sweeney, who wrote a screenplay based on Straight’s exploits and presented it to her longtime collaborator and partner, David Lynch.

“Richard [Farnsworth] has this wonderful old face with very young, deep blue eyes; they absolutely shone out. I never did anything too special, except to make sure that the audience would always see the actors’ eyes.”

— Freddie Francis, BSC

The tale immediately appealed to the always-off-the-beaten-path filmmaker, who soon approached venerable cinematographer Freddie Francis, BSC to shoot the unique road picture, entitled The Straight Story.

The recipient of Academy Awards for his work on Sons and Lovers (1960) and Glory (1989), and the ASC International Award in 1998 (see AC Mar. '98), Francis had first collaborated with Lynch on The Elephant Man (1980), and subsequently shot Lynch's ambitious sci-fi epic Dune [AC Dec. '84). The two men have remained close friends ever since.

Francis received a call and the script for The Straight Story from Lynch in the summer of 1998, just six weeks before the start of principal photography. Eager to work with Lynch again, Francis didn't hesitate to accept the project, but he did stipulate a maximum 10-hour shooting day. A spry octogenarian, Francis asserts, "I'm not doing 16- or 17-hour days anymore, but even at 10 hours, we still came in two or three days under schedule on the six-week shoot. There must be a moral there somewhere!"

Francis also requested that his longtime camera operator, Gordon Hayman, be brought aboard the show. Hayman had operated on the last three days of Elephant Man, and has operated for Francis on every one of his pictures ever since.

Over the course of his 60-years’ worth of experience in the film industry as both a cinematographer and director, Francis has found that creating the right mood in his photography is vital. "While talking to a director, it doesn't take me very long to understand the mood he is trying to get for his movie," the cameraman points out. "If he is the sort of person you want to work with, you can get into his mind. With David Lynch, I was on the same wavelength after a few minutes' talk, and for the rest of the movie we never discussed the photography."

Shooting began at the end of summer, with the landscape of Iowa stretching out before the filmmakers. Everything was to be done on location, and Lynch had already decided to shoot the picture in anamorphic. Simplicity and speed of operation were vital, and the only special effects would entail adding stars to a nighttime sky. "There was nothing 'George Lucas-y' at all," Francis says with a grin.

Francis employed Eastman Kodak Vision 200T 5274 for the majority of Straight Story, while he relied on Vision 500T 5279 for the film's night scenes. The equipment he utilized was straightforward: a Shotmaker camera car, a Panaflex GlI with C-series anamorphic lenses, a "normal" array of lighting gear, and one essential piece of equipment that the cameraman has used extensively: an Arriflex Varicon.

Francis had the Varicon (short for Variable Contrast) on the front of his camera at all times. However, the cinematographer admits that he is probably one of the very few people to use one. Originally developed as the "Colorflex" by British cameraman Gerry Turpin, BSC (see AC Jan. ’73), the device was adopted by Arriflex, re-engineered and renamed the Varicon. It consists of a matte box with a clear glass plate placed in front of the lens, which can be illuminated from the sides (in controllable increments) to reduce contrast in the scene or add color tints. Francis first used a Varicon on The French Lieutenant's Woman in 1981, and found that it had the secondary effect of slightly softening focus. "One trouble [for cinematographers] these days is that I think all of the newer lenses are almost too good," Francis contends. "I therefore try to knock some of the definition off them, [and the Varicon helps in that regard]."

Acutely conscious of the importance of time on the tight Straight Story schedule, Francis used as few takes as possible. Though he and Hayman made full use of their Shotmaker truck, he kept camera movement to a minimum. "If David wants camera movement, he wants good camera movement — not just, 'Oh, move the camera from here to there,'" Francis explains. "That takes time. I concentrate on doing the job as quickly as possible, because the less time I spend, the more time the director has. That, to my mind, is very important. I find that the Varicon speeds things up even more."

“If people want to see a charming film, and I sincerely hope they do, this is the one for them.”

Hayman chose the truck-mounted Shotmaker crane, with its very flexible configuration, specifically to enable him to get a wide range of shots quickly and easily. He says “it was one of the most important pieces of equipment in our kit.” Francis and Flayman made subtle use of the crane throughout the picture to emphasize Straight's excruciatingly slow progress. At one point early in the movie, they achieve a highly successful visual joke simply by exploiting the gentle rise and fall of the camera on the crane. The shot begins near road level, tightly framing the back end of Straight's mower as it travels along. The camera then rises suddenly to reveal a panoramic view of the highway stretching into the distance. After a long pause, the camera lowers back to its original composition, to find that the intrepid Straight's slow-but-steady headway can be measured in mere yards.

Francis strove to capture authentic Midwest ambiance and mood for The Straight Story. "We lapped up the atmosphere of Iowa and tried to put that on the screen to accentuate the plight of the old boy and his daughter, and to convey the poverty they were in," he notes. "The film then opened out once he took to the road. If you've ever been to Iowa and seen the fields of corn, they look pretty much the same. The place has a certain quality, but it's very flat with straight roads that go on forever." This feeling is well-represented in the picture by broad, swooping shots (made by aerial coordinator Bobby Zajonc and the second-unit crew) that establish the majestic scale and autumnal colors of the landscape.

Francis used a natural approach in his lighting. "When I was a kid starting out in the business," he reflects, "I became all too aware that on a good picture, the photography was always first-class but rarely had anything to do with the story. It was always brilliant and glossy regardless of the subject matter. If I've done nothing else in my career, I've really registered that point." Indeed, in The Straight Story, understatement serves to accentuate the clarity of the film's script and acting. Low-key interiors of bars reminiscent of Hopper paintings, as well as dramatic contrasts of weather and landscape, are injected only at essential points in the story. The accuracy of a given location is of special importance to Francis. The French Lieutenant's Woman was shot in Weymouth using the precise places described in the book, and the battle scenes in Glory were shot on the actual historical sites when possible. As Alvin Straight grinds his way across Iowa, over the Mississippi River, and into Wisconsin, Francis exploits the cinema verite qualities of the seemingly endless, flat topography. Francis came to Middle America as an outside observer with an objective view, but as the film progressed he was drawn into the story. "I suppose the great thing is, when I get on this sort of film, in a strange way I become one of the actors."

Francis notes that the progression of the seasons helped to reinforce the passage of time in the story. The tale begins in high summer as a woman sunbathes adjacent to Straight's house, but as autumn advances, the cornfields becomes "crackly and ripe," with harvesters working the fields in the background.

The cameraman testifies that the locations, and the lowans themselves, made an enormous contribution to The Straight Story. "One of the great things about the movie, which surprised me, was that we had so many local actors who were absolutely wonderful," Francis commends. "The small parts, vignettes really, were nearly all taken by local artists, who were invariably brilliant. We shot in their home environments, which must have made it easier for them. We even shot in the real home of Alvin Straight, which was very small for a set, but redolent with atmosphere."

Francis says he was particularly impressed by a long, minimally lit scene between Straight (Richard Farnsworth) and another old man (Leroy Swalley) in a bar, where the duo share anguished wartime memories. "The actors simply sat in a bar having a long talk," he reflects. "You may think. These two old boys can never hold this scene,' but they do. It is just that they are so alive — two old faces with young eyes.

"Richard [Farnsworth] has this wonderful old face with very young, deep blue eyes; they absolutely shone out. I never did anything too special, except to make sure that the audience would always see the actors' eyes. That is so important. Whatever your mood of lighting for a scene, it should change when you come to faces. There were a lot of close-ups of Sissy Spacek [as Straight's daughter, Rose] in the movie. She is very downtrodden, and you get that sense entirely from her eyes. I just hope the average cinema-goer appreciates that sort of thing."

Francis's one and only criticism of the production was the poor quality of the facilities used to screen dailies. Because of this drawback, the filmmakers only watched film rushes on the first day of the shoot. "I usually say, quite big-headedly, that I think I know what my photography is going to look like when I shoot it," the cameraman muses. "If there is anything technically wrong with the footage, the lab will soon let us know." Reared during the "no-frills," pre-reflex viewfinder era of cinema, Francis is not one to jump at the latest technical conveniences. "After our experience with the first day's rushes, we just got video dailies," he observes. "But since I think it is better not to see anything at all than to see dailies on video, I didn't view any more material during the shoot."

Additionally, the filmmakers elected not to use a video assist. The cinematographer delegates responsibility with absolute trust to Flayman, and reserves additional praise for the talents his key grip, Don Cerrone, dolly grip, Mike Fedak, and focus puller, Bill McConnell, brought to the production.

McConnell would pass on any important comment from the labs, but Francis notes that "unless disaster strikes, I keep out of my crew's way."

Fond of saying that "there are three kinds of photography: good photography, bad photography and the right photography," Francis believes he found the right photography for this heartfelt story. “If people want to see a charming film, and I sincerely hope they do, this is the one for them.”