Sundance Film Festival 2017 Standouts

Our veteran festival attendees make note of 10 projects that should catch the eye of those seeking exceptional cinematography.

“I must say, this year has put us to the test,” Sundance Film Festival director John Cooper confessed during the annual Park City event’s awards ceremony on January 28. “From a new government, to a women’s march that hit numbers of 8,000 — that’s in a very small town in the mountains — to power outages, to cyber attacks, to snow at record levels, we’ve all been challenged and changed these last 10 days.”

It was one for the memory books. While there was no obvious commercial break-out to emerge from this year’s Sundance screenings, there was an extremely strong slate of films, especially in the documentary categories. Submissions hit 14,000 this year, showing once again how vital Sundance exposure remains to independent filmmakers, who vied for the 187 coveted programming slots. That in mind, American Cinematographer’s three fest attendees here highlight 10 standouts that cinematographers should watch for.

MACHINES

Cinematography by Rodrigo Trejo Villanueva

Directed by Rahul Jain

Last year, I took a tour of a textile factory in Delhi. The sound was deafening, the machines antiquated, the safety measures nil. But that was Disneyland compared to the Dickensonian world of Machines, winner of the cinematography award in World Cinema Documentary. Pressed to complete an assignment at the California Institute of the Arts, director Rahul Jain remembered his grandfather’s Gujarat textile mill that he would visit as a child and found a comparable place. His film initially feels like a Frederick Wiseman doc, dispassionately observing the tasks of men and machine in a dehumanized world. But then, the workers speak. And boy, what a dire existence.

Though sparse in number, these informal interviews reveal worlds about the Indians’ desperation for work, the obstacles to unionizing, and the boss’s belief that full bellies equal a lazy workforce. Mexican cinematographer Rodrigo Trejo Villanueva — once a factory worker himself — effectively captures the mind-numbering work, like when his camera lingers on a hand pressing a button every two seconds, presumably for the entire 12-hour shift. It’s mesmerizing and horrifying; an infernal world in chiaroscuro. — Patricia Thomson

LAST MEN IN ALEPPO

Cinematography by Fadi al Halabi and Thaer Mohammed

Directed by Feras Fayyad

Documentary jurors had no debate over the Grand Jury prize, which went to Last Men in Aleppo, by Syrian director Feras Fayyad and Danish codirector/editor Steen Johannessen. “This extraordinary film lifted us, carried us, and dropped us into a place unlike any other film,” said juror Lynette Wallworth. The verité project follows Khaled, Mahmoud, and Subhi, ordinary men doing extraordinary things as founders of the White Helmets, Aleppo’s first responders. After five years of siege, they feel the noose tightening. We watch them search the skies for barrel bombs — improvised aerial weapons dropped from government helicopters — and then head straight into the smoking aftermath, using bare hands and backhoes to dig out babies, adults and severed limbs. Director of photography Fadi al Halabi and cinematographer Thaer Mohammed stick close, even in life-threatening situations. They capture the emotional highs and lows of rescue work, interspersed with scenes of domestic life: buying goldfish for a courtyard fountain; taking the kids to a playground during a ceasefire; joshing with two young, adoring daughters at home. What happens to these men remains burned in your brain for days. — Patricia Thomson

STRONG ISLAND

Cinematography by Alan Jacobsen

Directed by Yance Ford

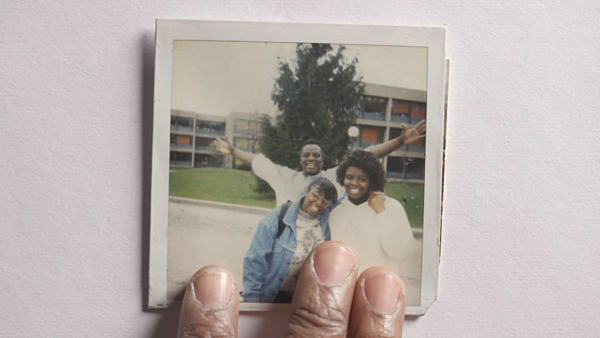

Winner of a Special Jury Prize for Storytelling, Strong Island falls under the rubric of first-person documentary, but stylistically it’s in a category by itself. Decades after the 1992 murder of his brother, director Yance Ford decides to investigate what actually happened and why the assailant was let free with nary a slap on the wrist. This is a story of racial injustice, William Ford being killed by a white auto mechanic after an altercation, posthumously criminalized by prosecutors, and judged by an all-white jury. But it’s also the story of a family and how this cohesive unit spins apart in the aftermath. Ford, for 10 years a series producer at POV, here works with cinematographer Alan Jacobsen to create a unique visual vocabulary. Restricted framing acts as a metaphor for Ford’s inability to get the whole picture. Mounted on a still-camera tripod head, the camera never pans or tilts, but people and objects move in and out of the fixed frame. Faded, dog-eared family photos are slid onto a table. Depopulated family rooms linger before our gaze. Subjects talk straight to the lens, the shots long and unbroken. This direct, prolonged eye contact is unusual for filmed interviews, and it’s a bit unnerving, looking deep into the window of a broken soul. But it’s absolutely appropriate for this searching, emotionally immersive film. — Patricia Thomson

FRANTZ

Cinematography by Pascal Martis, AFC

Directed by François Ozon

The latest from French director François Ozon is Frantz, a World War I drama that feels at once classic and up to the minute. A German woman is mourning her fiancé, killed on the battlefields of France. One day she discovers a Frenchman weeping at his grave. Taking him for a friend from her fiancé’s student days in Paris, she invites him over. While she and the in-laws form deepening bonds with this mysterious stranger, the town is overtly hostile, seeing any Frenchman as an enemy to be expelled. Midway, the film takes an unexpected turn. The Frenchman returns to Paris, the girl follows, and suddenly she’s the one facing icy glares and nativist hostility. The political resonance is so acute it was a shock to see Ernst Lubitsch’s name on the credits. His Broken Lullaby (1931) shared the same source material: a play by Maurice Rostrand written shortly after the war. But Ozon jettisons their happy ending and adds the entire second half — a masterful stroke. Working again with Pascal Martis, AFC, Ozon went for a wholly original look: black-and-white that occasionally blossoms into color. Sometimes the shift is structural, indicating a flashback; sometimes it’s emotional, tied to lying or happiness. “[It] suggests life bleeding back into this gray period of mourning,” Ozon has said. “As blood runs through veins, color irrigates the black and white of the film.” — Patricia Thomson

THEIR FINEST

Cinematography by Sebastian Blenkov

Directed by Lone Scherfig

A delectable treat for cineastes is Their Finest, a film about filmmaking in Britain’s Ministry of Information during the 1940 Blitz. It opens with an atrociously bad propaganda short — an actual film that was shelved by the ministry (and saved by the British Film Institute). Its ridiculously lame dialog motivates the first plot point: The ministry decides they need a woman to help juice up the “slop,” as female dialog was called. They hire a novice wordsmith, who’s then recruited to co-write an epic feature on the rescue at Dunkirk — to be shot in brand-new Technicolor.

In this adaptation of Lissa Evans’ 2009 novel Their Finest Hour and a Half, Danish director Lone Scherfig has crafted a female-strong film that seamlessly slips between drama and comedy (Bill Nighy’s vain, over-the-hill matinee idol is worth the price of admission). It’s also a love letter to the craft of filmmaking. Danish director of photographer Sebastian Blenkov must have had a field day recreating the propaganda films, wartime newsreels, and especially the marvelous, candy-colored Technicolor treat. “One of the biggest challenges was to make all of these elements marry and feel logical, so you didn’t feel the effort to make it work,” the director said in a Q&A. She needn’t have worried. The film seamlessly portrays an era when Britain’s finest were also behind the lens. — Patricia Thomson

78/52

Cinematography by Robert Muratore

Directed by Alexandre O. Philippe

A cineaste’s meditation on the iconic shower scene in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, the documentary 78/52 offers insightful observations about the famous sequence from a variety of informed sources, making it mandatory viewing for anyone seeking a deeper appreciation of cinema.

The title refers to the 78 setups and 52 cuts required to shoot and edit the three-minute shower sequence, which caught viewers completely off guard when Psycho was released in 1960. Unaccustomed to seeing a movie’s female lead butchered in the first third of a picture, audiences reportedly screamed in primal terror as the grisly scene unfolded, not noticing that through clever editing, the knife wielded by cross-dressing serial killer Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) is never actually shown penetrating the flesh of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh).

One of the most famous scenes in movie history, the shower sequence certainly merits the in-depth analysis 78/52 provides. The scene is autopsied from every angle, with commentary provided by notable film directors, including Peter Bogdanovich, Guillermo Del Toro and Eli Roth; master editor Walter Murch, who breaks down Hitchcock’s frame-by-frame construction; film composer Danny Elfman, who analyzes Bernard Herrmann’s inspired use of shrieking violins to amp up the scene’s visceral horror; filmmaking partners Elijah Wood, Josh Waller and Daniel Noah, who focus in on the performances of the two lead actors with the unbridled enthusiasm of true fanboys; film historians Stephen Rebello and David Thompson; Osgood Perkins and Jamie Lee Curtis, the son and daughter of the Psycho stars; and Marli Renfro, the Playboy Bunny who served as Janet Leigh’s body double.

Even those who have fetishized Psycho after countless viewings will find the documentary’s myriad details both illuminating and entertaining — such as a sequence that reveals how Hitchcock finally found the perfect stabbing sound after obsessively testing a hundred different kinds of melon with a butcher knife. (“Casaba” was his droll final verdict.)

The documentary’s cinematographer, Robert Muratore, adds an elegant touch of homage in stylized re-creations of various Psycho scenes, all shot in dreamlike black-and-white to echo the look of Hitchcock’s motel-noir masterpiece.

The sum total of the presentation is a respectful and extremely appreciative overview of a sequence that has achieved pop-culture immortality not only through its initial impact, but through repeated viewings by fans and film scholars. — Stephen Pizzello

COLUMBUS

Cinematography by Elisha Christian

Directed by Kogonada

A movie about “architecture nerds” should be aesthetically compelling, and Columbus cinematographer Elisha Christian helps director Kogonada meet this criterion in spectacular fashion.

Set in Columbus, Indiana, where notable examples of Modernist structures co-mingle with 19-century styles, the movie centers on Casey (Haley Lu Richardson), a local girl with an eye for design who feels obligated to pass up her own dreams and ambitions in order to provide emotional support for her mother (Michelle Forbes), a recovering drug addict.

Casey’s hand is forced when she meets Jin (John Cho), the son of a renowned architect who has collapsed and fallen into a coma during a scholarly tour of Columbus. Both stranded in town by personal circumstances, Casey and Jin quickly form a bond; surprised that Jin seems disinterested in his father’s profession, Casey attempts to enlighten him with a guided tour of Modernist masterpieces by famous architects such as Eero Saarinen, I.M. Pei, Deborah Berke, Harry Weese and others — reigniting her own passion for the sublime artistry that makes Columbus a Mecca for architecture buffs.

In framing this relationship, Christian and Kogonada craft a film filled with strikingly elegant compositions that honor the city’s imaginative structures, which provide a meditative backdrop to the story’s melancholic themes and tone. These quiet, contemplative scenes imbue Casey’s existential conflict with a subtle, gathering power, rewarding patient viewing with an emotional payoff that echoes the movie’s thoughtful and visually pleasing proscenium.

As the sum of its meticulous details, Columbus is a film with considerable feng shui for anyone who appreciates both stunning architecture and the harmony of beautifully structured cinematography. — Stephen Pizzello

BUSHWICK

Cinematography by Lyle Vincent

Directed by Cary Murnion and Jonathan Milott

Bushwick presents an apocalyptic scenario that might seem more outlandish in a less divided United States: a second Civil War has erupted, with Texas leading a coalition of Southern states in an aggressive military action within the nation’s borders. The movie’s action is focused on one battleground within the larger conflict: the Brooklyn neighborhood of Bushwick, where a hostile and heavily armed Texas militia is attempting to secure the immediate region.

In a striking and unnerving opening sequence set on a subway platform, grad student Lucy (Brittany Snow) and her boyfriend gradually notice the eerie silence that surrounds them in the strangely abandoned space. A warning announcement over the platform’s P.A. system ratchets up the tension before a hellish vision interrupts the couple’s approach to the nearest exit; after several horrifying moments of mayhem, Lucy is left to fend for herself aboveground on streets that seem more like Iraq than a working-class borough of New York City.

Lucy eventually meets a reluctant guardian angel in the form of Stupe (Dave Bautista, in an effective and affecting action-hero turn), a military veteran who helps her wend a perilous path through gunfire, explosions and other threats to life and limb. Along the way, the two attempt to rescue Lucy’s grandmother and sister while encountering a roaming series of intimidating enemies and potential allies.

This B-movie concept achieves surprising traction thanks to the rapport of the two leads and the dynamic handheld camerawork of cinematographer Lyle Vincent (who also shot Thoroughbred, one of the 2017 Sundance Festival’s biggest acquisitions, and whose credits also include the inventive, sumptuously shot black-and-white vampire film A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, which drew accolades at Sundance in 2014). Following the action in kinetic long takes cleverly edited to appear as one nearly unbroken shot, Vincent adrenalizes the narrative and helps elevate the narrative’s pulp concept to more propulsive heights. A number of surprising detours enhance the movie’s serpentine journey before the bedlam escalates to a wild climax that plays out like a hair-raising, first-person shooter game. In short, Bushwick is a blast. — Stephen Pizzello

NOVITIATE

Cinematography by Kat Westergaard

Directed by Margaret Betts

Directed by Margaret Betts and shot by Kat Westergaard, Novitiate is the story of a young woman named Cathleen (played in her late-teen years by Margaret Qualley), who finds in the halls of her Catholic church a deep, spiritual and arguably romantic love of God. Against the will of her mother, Cathleen enrolls at a convent and progresses toward an intense training period called the novitiate — a process, which she experiences along with her fellow novices, that culminates in the taking of the nun’s vows.

The movie for the most part features smooth and subtle camerawork, such as slow tracking within wide shots of nuns walking in procession, and adept use of overcast skies for compelling exteriors. The move to handheld for scenes in Cathleen’s home was quite effective in communicating a chaotic family life — even foreshadowing a nasty fight between her parents, the shaky frame providing a volatile mood before her dad even walks in the door.

Inside the convent, there was prominent use of backlight from blown-out windows, some terrific beauty shots after dark, and distinctly discomforting candle-motivated light that illuminates the girls when they’re called by the Reverend Mother (Melissa Leo) to confess their shortcomings. Comfort, security, loneliness and isolation are all equally accounted for. — Andrew Fish

MUDBOUND

Cinematography by Rachel Morrison, ASC

Directed by Dee Rees

Mudbound tells the tale of a white family that owns a farm and a black family that works the land. The movie begins as Laura (Carey Mulligan) marries Henry McAllan (Jason Clarke) mainly for practicality and security, while she clearly has a connection with Henry’s charismatic brother, Jamie (Garrett Hedlund). Her life is upended a few years later, toward the end of World War II, when Henry announces that they, their kids, and his belligerent and intolerant father (Jonathan Banks) will be moving to the Mississipi farm Henry’s just bought.

Meanwhile, Hap Jackson (Rob Morgan) and his wife, Florence (Mary J. Blige), struggle to raise their family and make ends meet while sharecropping on that very farm, laboring to save enough money for a piece of land of their own. When both their son Ronsel (Jason Mitchell) and Jamie return from war, the two men form a bond in a time and place in which such friendships are shunned.

Directed by Dee Rees and shot by Rachel Morrison, ASC, Mudbound is a beautiful depiction of a tumultuous time. Toil and sweat, inequity and violence, friendship and love against a backdrop of the American South. Daytime shots in the fields are composed like paintings with judicious use of magic-hour light, while interiors run the gamut. The Jackson’s house is cramped yet warmed by fire- and candlelight, and sequences inside a fighter plane are tense, harrowing and pack a punch. There’s a particularly memorable shot of a pickup truck framed through the front windshield, with Jamie at the wheel and Ronsel way in the back — a scene that takes place shortly before Jamie points out that the distance between the two of them is due to a preposterous worldview. After that, Ronsel rides up front with Jamie, a dynamic that rouses bad feelings throughout the town.

A couple of fantastic night exteriors respectively feature Hap dancing with Florence outside their house, and Ronsel giving her a bar of chocolate — companion moments that celebrate a woman who fights hard to keep her family safe, intact and on task. — Andrew Fish

AC will profile a number of Sundance titles in greater depth over the next few months, both online and in print.