The Techniques of Kazuo Miyagawa

Observations of Japan’s eminent cinematographer at work.

This article originally appeared in AC, Jan. 1960.

Naming the most skillful cinematographer of a country often is a difficult task. In Japan the job has been simplified somewhat by the international reputation which has been earned by Kazuo Miyagawa.

Miyagawa was responsible for the photography of Japan’s most famous films, Rashomon and Ugetsu. More recently, he has done equally fine camerawork on Kagi [Odd Obsession], which is destined for world-wide distribution, and Enjô [Conflagration], Japan’s entry in the 1959 Venice Film Festival.

Donald Richie, co-author of the book The Japanese Film, said of the photography in the latter picture: “Miyagawa used widescreen as it has seldom been used before, or after, capturing in black and white textures and surfaces so perfectly that the screen at times almost resembled a bas-relief.”

“I am never satisfied. I rarely look at what I have done in the past. Instead, I continually strive to find new ways of filming more effectively in the future.”

— Kazuo Miyagawa

Part of Miyagawa’s eminence can be attributed to his versatility. The Japanese cinematographer regularly handles with equal facility and skill, black-and-white or color assignments, in standard or widescreen format, involving historical or modern day screenplays.

While visiting Miyagawa at Daiei’s Tokyo studios, we were somewhat surprised to learn that he prefers to shoot in black-and-white in the standard format despite the fact some of his recent successes have been in color and widescreen. He carries his preference for the old “3-by-4” format into his widescreen work, using his company’s Daieiscope widescreen system as if he were employing the standard aspect ratio.

In explanation he pointed out that the rooms in Japanese houses and buildings often are small. When they are reproduced on the sound stages there is little chance to compose pictorially for the full widescreen. As a result, Miyagawa has developed a unique system of sectional use of the picture’s width to overcome this problem.

In this approach he leaves large sections of the frame shrouded in darkness, but at the same time with artful lighting cleverly guides the eye of the viewer to the area in which the director has placed his center of interest.

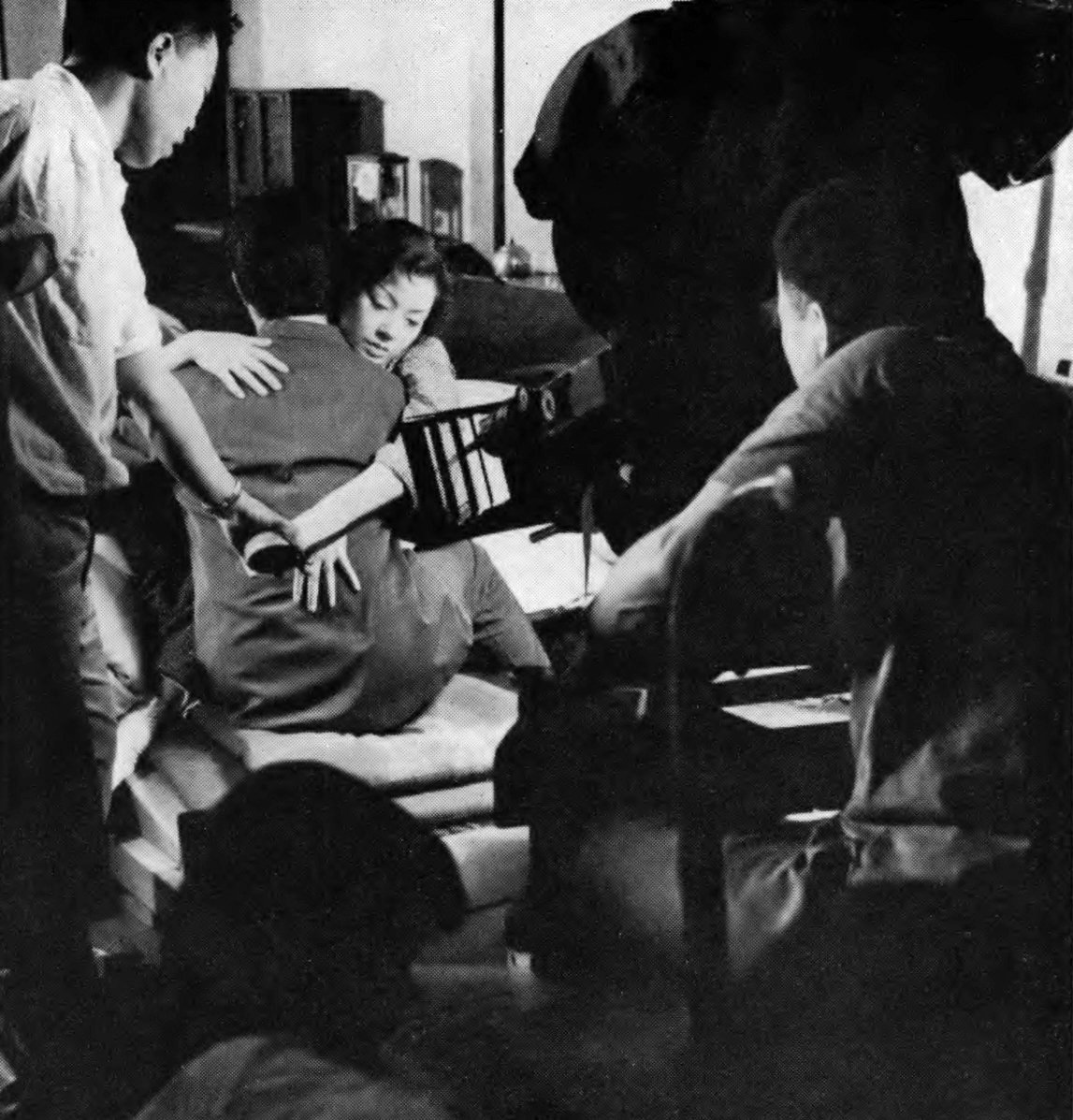

In one sequence of Kagi the action is seen through an open door at one side of the frame. The rest of the screen is barely illuminated. The viewer receives the impression that he is eavesdropping on the characters, an effect extremely desirable at this point in the plot.

The story of Kagi lays bare the sordid emotions of an elderly man. Miyagawa achieved a forceful visualization of this theme by reducing the colors to tones approximating those of black and white. In many scenes there are strong highlights and deep shadows not often seen in color productions, but in this case they further enhance the story.

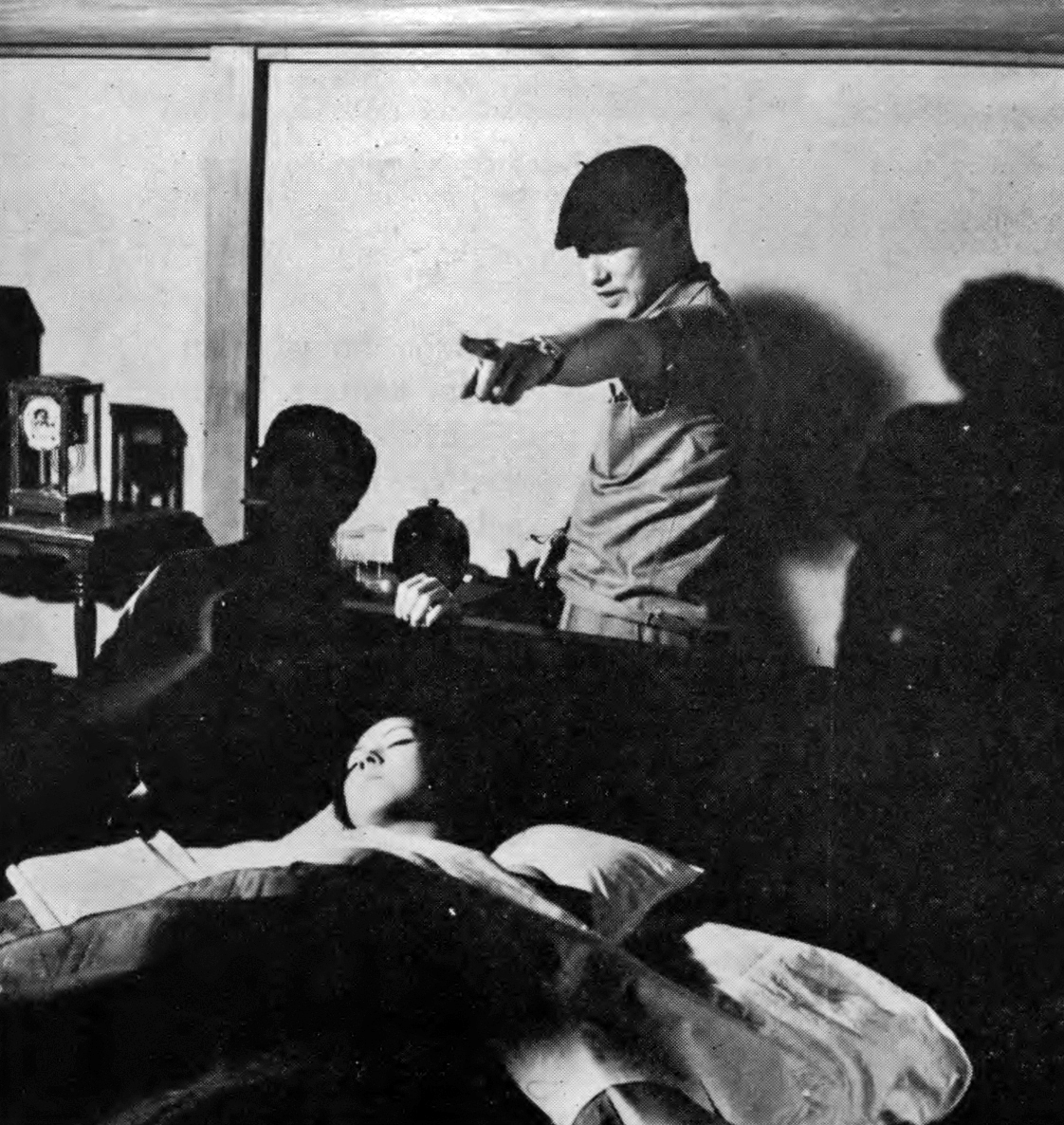

In one sequence the old man’s doctor tells him that he is in danger of becoming seriously ill. Miyagawa’s key-lights come through the opaque panels of sliding doors at one side of the room, illuminating the old man’s face, but leaving the doctor’s features hidden in shadow. Thus the viewer’s eye is riveted to the expressions of the man as he hears the disturbing news.

This sequence, among others, reveals Miyagawa’s penchant for realistic lighting. The particular set-up described above was drawn from the Japanese cameraman’s memories of the dark rooms of his childhood home.

In the moving story of a young student who sets fire to the famed Golden Pavilion in Kyoto, Miyagama’s camera is given a heavy burden. The picture’s effectiveness depends largely upon the great force with which he depicted the emotions behind the young man’s actions.

An especially taut sequence shows the youth and his mother talking heatedly in an underground air raid shelter. The only light source is an open door. Miyagawa shot the action in silhouette, forcing viewers’ eyes toward the stark outlines of the actors’ faces. Some photographers might have used fill lights here and destroyed much of the dramatic impact.

Despite Miyagawa’s success in modern-day films, his first love is the historical costume play which brought him international fame.

"These pictures I believe come close to giving a true impression of the real Japan,” he said.

Rashomon and Ugetsu long will be remembered and studied for their exotic photography which played a major part in both films’ success outside Japan.

Miyagawa revealed a secret of sorts when he stated he did not heavily filter the misty, dream-like settings used for these two pictures. Although he uses filters frequently on many assignments, he photographed the locations for Rashomon and Ugetsu almost as he found them.

Large portions of Japan’s costume dramas are filmed on location in the Kyoto area, which is rich in natural and man-made beauty. Miyagawa has drawn much inspiration for his camerawork from these scenic spots.

Daiei and other Japanese film companies maintain sound stages in the ancient city to take advantage of the surrounding pictorial beauty. Half of Daiei’s annual product is said to be made there; and so Miyagawa is kept hopping between Tokyo and Kyoto as his assignments change from the modern to the historical.

In these Japanese studios, Miyagawa works under conditions which are different from those usually found in Hollywood. But to him and his fellow Japanese directors of photography they are the norm.

As we watched him at work on the set, we observed that Miyagawa had the help of four assistants. Nevertheless, when the time arrived to do the actual shooting, he operated the camera himself. Here many directors of photography will not trust the framing of their pictures to anyone but themselves.

Although Miyagawa had fewer set lights to work with than do most Hollywood cameramen, he still had more than many Japanese cinematographers have at their disposal on lesser productions.

He shoots his black-and-white films at about 250 foot-candles on Fuji stock, which he rates at 120 ASA. For particularly difficult jobs he uses the old standby, Eastman Tri-X.

As we watched Miyagawa at work on his current color film, Ukikusa [Floating Weeds], he was using only 450 foot-candles of illumination on a well-lit interior. For color productions either Eastman or Agfa film is used, he said.

The set lighting arrangements in Japanese studios are left largely in the hands of the Nipponese equivalent of the head gaffers in Hollywood. But Miyagawa, because of his stature as a cinematographer, spots most of the lights on his sets.

Because most of the sets are diminutive, it is often a problem to find enough space to wedge in lights; many times electricians hand-hold fill lights, because there is little or no room for mounting the lamps on standards.

Frequently a tripod will not fit on a Japanese set. Miyagawa, like many other Japanese cinematographers, uses a series of triangular frameworks of wood for mounting the camera at the varying heights he requires. As we watched him at work on Ukikusa, we noticed that very often his camera was only two feet above the floor level, a common height for Japanese films in which the actors spend much of their time kneeling.

Miyagawa was working with a Mitchell NC [Newsreel Camera] instead of the Hollywood standard, the BNC. To deaden camera sounds, a Barney was invariably used. When more ‘"blimping'" was needed, an assistant threw a blanket over the camera.

Miyagawa never had to worry about mike boom shadows simply because no conventional mike boom was used. Japanese sound men, since the very early days of sound, have taped their microphones to bamboo poles and lowered them into the sets from the catwalks overhead.

Lengthy pre-production planning is a luxury which is afforded Miyagawa over other cinematographers. Because he presently shoots only two or three pictures a year, he is usually given four weeks to study a script, whereas most other Japanese cinematographers get a flat two weeks to plan their work.

Once a film has begun, Miyagawa is in the scramble on the sound stage with the rest. Production seldom falters until a picture is finished. Saturdays and Sundays are also work days on the Japanese lots.

Many films at Daiei are allotted a straight 45-days schedule from the time the camera first turns until the film is ready for showing. Nothing short of disaster ever stops these schedules.

Front-office policy allows Miyagawa to shoot at a ratio of only two-to-one. Thus, for every shot there are always several rehearsals for action, sound and camera.

In discussing the highly praised Japanese color photography, Miyagawa pointed out one important factor which must be considered in any evaluation. The Japanese need approximately only 50 prints for their distribution, he said, while larger countries like the U.S. usually require hundreds. As a result, the Japanese use the original negative for release printing, increasing the chances for better tonal quality in the final prints.

Miyagawa’s motion-picture career began 32 years ago, after he failed his high school entrance examinations and was forced to seek steady employment. It was the Japanese policy at the time that neophyte cameramen start their apprenticeships in the darkrooms. Miyagawa stayed four years in the old Nikkatsu studio lab. Later he was promoted to assistant cameraman. In 1936 he became a director of photography. Since that time he has photographed 75 feature-length films.

Despite his acknowledged skill, Miyagawa is always studying new developments and techniques. He is an avid reader of American Cinematographer.

Miyagawa, like most competent cinematographers, is not a person to rest on his laurels. He indicated his philosophy of photography when he confided: “I am never satisfied. I rarely look at what I have done in the past. Instead, I continually strive to find new ways of filming more effectively in the future.”

Shortly after the publication of this article, Miyagawa re-teamed with Rashomon director Akira Kurosawa on 1961's Yojimbo. The duo eventually made a third feature together, the poetic war epic Kagemusha, in 1980.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.